Baltimore Polytechnic Institute

| The Baltimore Polytechnic Institute | |

|---|---|

| |

| Address | |

| |

, 21209 United States | |

| Coordinates | 39°20′48″N 76°38′41″W / 39.34677°N 76.64469°W[1] |

| Information | |

| School type | Public, Secondary school, High School and "Magnet" school, (formerly single sex school, all - male, 1883-1974) |

| Motto | "Uniting Theory and Practice" |

| Established | 1883 - on east side of old Courtland Street (in the 300 block, later renamed St. Paul Street/Place in 1919) and north of East Saratoga Street (opposite present-day terraced "Preston Gardens", on site of current campus of Mercy Hospital / Medical Center) |

| School board | Baltimore City Board of School Commissioners (est. 1829) |

| School district | Baltimore City Public Schools (est.1829) |

| Superintendent | Dr. Sonja B. Santelises [CEO] |

| President | (student government) |

| Director | Jacqueline Willams[2][3] |

| Faculty | 88[4] |

| Grades | 9–12 |

| Gender | 49% male; 51% female[5] |

| Enrollment | 1647[5] |

| Area | Urban |

| Color(s) | Orange and Blue |

| Song | "Poly Hymn" (tune: "Eternal Father, Strong to Save" / "Navy Hymn") |

| Fight song | "Poly Fight Song" |

| Athletics conference | Maryland Public Secondary Schools Athletic Association (MPSSAA) since 1993 [formerly in the Maryland Scholastic Association - (MSA, 1919-1993)] |

| Sports | 23[5] |

| Mascot | "Poly Parrot" |

| Nickname | B.P.I.; Poly; Polytechnic; Tech; The Institute |

| Team name | "The Engineers" |

| Rivals | The Baltimore City College ("The Black Knights"- since 1950 / "The Collegians" - since 1870s) |

| USNWR ranking | 2,167[4] |

| Newspaper | "The Poly Press" (est. 1909) |

| Yearbook | "The Poly Cracker" |

| Budget | $10,748,593.00 (fiscal year 2014)[6] |

| Website | www |

The Baltimore Polytechnic Institute, colloquially referred to also as BPI, Poly, "Polytechnic" and The Institute, is a U.S. public high school founded in 1883. Though established as an all-male manual trade / vocational school by the Baltimore City Council and the Baltimore City Public Schools, it is now a coeducational academic institution that emphasizes sciences, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). It is located on a 53-acre (21 ha) tract of land in North Baltimore on the east bank of the Jones Falls stream which runs from the north near the "Mason–Dixon line" border between Maryland and Pennsylvania to the south emptying in the Northwest Branch of the lower Patapsco River/Inner Harbor between downtown and Fells Point. Also running parallel to the extensive Poly campus is the Jones Falls Expressway (Interstate 83). The institute is located at the northwest intersection of Falls Road (Maryland Route 25) and West Cold Spring Lane, in northwestern Baltimore City, bordering the neighborhoods of Cross Keys to the north, Roland Park to the east, Hampden to the south, Woodberry to the southwest and I-83 /Jones Falls stream and Coldspring neighborhood to the west and Park Heights and Pimlico further northwest. BPI and the adjacent Western High School (founded in 1844, it's the oldest all girls public high school in America and one of the oldest compared to private/independent/secular single sex schools as Poly formerly was until 1974) are located on the same joint campus since 1967, share several amenities including a cafeteria, auditorium, center courtyard and athletic fields, as well as a collaborative marching band recently united, now known as "The Marching Flock" (referring to the two schools' mascots – The "Poly Parrot" and the Western High's "Doves").[7] BPI is a "Maryland Blue Ribbon School of Excellence" cited by the Maryland State Department of Education.[8]

History

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2015) |

BPI was founded in 1883, after Joshua Plaskitt petitioned the Baltimore City authorities to establish a school for instruction in engineering, sciences, mathematics and technology. The original school was named the Baltimore Manual Training School, and its first class was made up of about sixty students, all of whom were male. The official name of the school was changed and upgraded a decade later in 1893 to "The Baltimore Polytechnic Institute" by the Baltimore City Board of School Commissioners. The first three principals were Dr. Richard Grady, Lieutenant John D. Ford (U.S.N.), and Lieutenant William King (U.S.N.), after whom one of the three main campus buildings – King Memorial Hall was named in the 1980s. Having two naval officers as chief academic leaders gave a unique "naval flair" and military emphasis to the new Institute's program and policies. The first building was located on the former site of the 18th and early 19th century old central City Spring, which was landscaped as a small park/plaza on Courtland Street, just north of East Saratoga Street and west of adjacent North Calvert Street. This area was later contained in Baltimore's first downtown "urban renewal" plan with the tearing down of five square blocks of now significant architecture townhouses along Courtland and Saint Paul Streets to the west. Resulting in the construction of terraced "Preston Gardens" (constructed 1914-1919) and laying out of Saint Paul Place, from East Centre Street in the north to East Lexington Street in the south, adjacent to the Baltimore City Courthouses. The former BMTS / BPI building (and an earlier elementary school dating back to the 1840s) after Poly moved to North Avenue in 1913, subsequently in the 1930s became home to the new Baltimore City Department of Public Welfare offices and was later annexed by neighboring Mercy Hospital (formerly named originally as Baltimore City Hospital) facing east on North Calvert and East Saratoga Streets. This old first Poly building of 1883-1913 / Dept. of Public Welfare structure later was torn down for construction of Mercy's first hospital tower, McCauley Building in 1964. In 1983, at the B.P.I. centennial observation, a historical bronze plaque was placed in the lobby of the hospital commemorating that earlier first home of the original Manual Training School, later to be renamed B.P.I. for 30 years. It just so happened in an amazing coincidence, that this first BPI building also was across the street and 44 years later, (almost a half-century later) after their long-time archrival public high school The Baltimore City College ("City") was also established in a row house in 1839 for a few short years in the 1840s, also began on the now vanished narrow alley-like Courtland Street.

Relocation

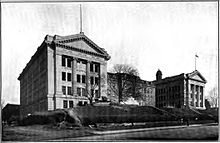

Due to continued growth of the student population of the BCPS and especially in the growing demand for higher secondary education at high schools like at BPI and BCC and the girls schools, the technical school relocated in 1913 to Calvert Street and North Avenue. The former 1860s converted mansion of the Maryland School for the Blind was purchased sitting on a slight hill and two massive wings on the east and west sides were added with a Greek Revival style columns on the front facade. For the first time in its 30 years history "Tech" had a suitable building expansive enough to handle both its academic and technical education requirements. By 1930, the old original central wing of "The Mansion" was razed and replaced by a simpler center wing between the two flanking 1913 structures with an additional large enormous auditorium/gymnasium wing further to the east facing North Avenue were constructed. This massive assembly hall was the largest at the time in the city and served many secular/civic/cultural occasions and events for decades into the mid-1980s. While at this location, the school expanded both its academic, technical and athletic programs under the extensive longtime supervision of Dr. Wilmer Dehuff, who was fourth principal from 1921 to 1958 and reluctantly (see below) oversaw the racial integration of the school in 1952, the first instance in City of Baltimore public schools with admitting African-American/then called "Negro" – "Colored" students and two years before the rest of the nation took up this serious issue of discrimination addressed finally by the Supreme Court of the United States in May 1954 in the famous case of Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. Previous black students had attended Frederick Douglass High School (formerly the "Colored High School" – second oldest in the nation – founded the same year as Poly – 1883) and the Paul Laurence Dunbar High School [9][10] Dehuff later served after his 37 years career at Poly, as the president and dean of faculty at the University of Baltimore on Mount Royal Avenue.

Integration/desegregation

Most Baltimore City public schools were not integrated until after the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education. BPI had an unusually advanced and difficult college engineering "A" preparatory curriculum which included calculus, analytical chemistry, electricity, mechanics and surveying; these subjects were not offered at the black high schools in the city before 1952.[11] BPI was a whites-only school but supported by taxes on the general population. No black schools in the city (black students could not attend whites-only schools) offered such courses, nor did they have classrooms, labs, libraries or teachers comparable to those at BPI City College. Because of this a group of 16 African American students, with help and support from their parents, the Baltimore Urban League and the NAACP, applied for the engineering "A" course at the Poly;[12] the applications were denied and the students sued.

The subsequent trial began on June 16, 1952. The NAACP's intentions were to end segregation at the 50-year-old public high school. In the BPI case they argued that BPI's offerings of specialized engineering courses violated the "separate but equal" clause because these courses were not offered in high schools for black students. To avoid integration, an out-of-court proposal was made to the Baltimore City school board to start an equivalent "A" course at the "colored" (for non-whites) Frederick Douglass High School. The hearing on the "Douglass" plan lasted for hours, with Dehuff and others arguing that separate but equal "A" courses would satisfy constitutional requirements and NAACP attorney Thurgood Marshall arguing that the plan was a gamble and cost the city should not take. By a vote of 5–3, the board decided that a separate "A" course would not provide the same educational opportunities for African American students, and that, starting that fall, African American students could attend Poly.[13] The vote vindicated the NAACP national strategy of raising the cost of 'separate but equal' schools beyond what taxpayers were willing to pay.[14] Thirteen African American students, Leonard Cephas, Carl Clark, William Clark, Milton Cornish, Clarence Daly, Victor Dates, Alvin Giles, Bucky Hawkins, Linwood Jones, Edward Savage, Everett Sherman, Robert Young, and Silas Young, finally entered the school that fall. They were faced daily with racial epithets, threats of violence and isolation from many of the more than 2,000 students at the school.[15] The first of those students to graduate from Poly was Dr. Carl O. Clark in 1955. Dr. Clark went on to become the first African-American to graduate from the University of South Carolina with a degree in physics in 1976.

Modern campus (1960s–present)

In 1967, then-principal Claude Burkert (1958–1969) oversaw the relocation of his school to its current location at 1400 West Cold Spring Lane, a fifty-three-acre tract of land bordering Falls Road and Roland Park. Also occupying this site is the Western High School, an all-girls school founded in 1844. Notable buildings on the campus include Dehuff Hall, also known as the academic building, where students attend normal classes, and Burkert Hall, also called the engineering building, where students attend classes in the Willard Hackerman Engineering Program. Both Western High School and Poly students make use of the auditorium/cafeteria complex, and likewise share the swimming pool and sports fields. Although the two schools share these facilities, their respective academic programs and classrooms are completely separate from one another.

In 1974, Poly officially became coeducational when it began admitting female students. The first female to enroll and successfully graduate from the "A" course was an African-American named Cindy White (1974–1978). In the late 1980s, the title "principal" was changed to "director." After the retirement of Director John Dohler in 1990, Barbara Stricklin became the first woman to head the school, as she accepted the title of Interim Director.

During Director Ian Cohen's tenure (1994–2003), Poly's curriculum was again expanded when it began offering Advanced placement (AP) classes. During the 2001–2002 school year, Poly was recognized by the Maryland State Department of Education when it was named a "Blue Ribbon School of Excellence."[8] In 2011, Poly was ranked 1552 nationally and 44 in Maryland as a "Silver Medal School" by U.S. News and World Report.[4]

In 2004, Dr. Barney Wilson, a 1976 Poly graduate, became Baltimore Polytechnic Institute's first African-American director. In August 2010, assistant principal Matthew Woolston, was appointed interim director. Later on during the year, Jacqueline Williams was appointed as interim director for the 2011–2012 school year. By the end of the school year – and after a two-year, nationwide search – Williams became the first female director of the institution. Williams worked her way through the Poly ranks from student (Class of 1981), to teacher, then department head, to assistant principal, and to dean of students, before appointment to her current position as director.[2]

Academics

Poly is a magnet school with specialized courses drawing students from across Baltimore's regular district boundaries. Admission to the school is highly competitive. Course concentrations include: the Honors STEM Program; the Ingenuity Project offering advanced science and math in conjunction with area universities; AP Capstone emphasizing Social Sciences and Humanities; and Computer Science.[16] In its 2019 nationwide survey of STEM programs spanning 2015–2019, Newsweek ranked Poly #36 among US high schools.[17]

Athletics

In addition to the school's football program, Poly's sports include basketball, soccer, cross-country, track and field, lacrosse, baseball, hockey, swimming, tennis, volleyball, and wrestling.[18] The boys' basketball team won three state championship titles in a row between 2016 and 2019.[19] The Poly Engineers baseball team has won nine Baltimore City championships since 2005 under head coach Corey Goodwin.[20]

Football

Since the early 1900s the Engineers, along with City College, had dominated the Maryland Scholastic Association (MSA) football scene. However, since joining the MPSSAA in 1993, Poly made it to the final game once in 1993, the semifinals once in 1997 and the quarterfinals in 1994 and 1998.[21]

Poly and City

The City–Poly football rivalry, also referred to as the "City-Poly game" is an American football rivalry between the Baltimore City College Black Knights (City) and the Baltimore Polytechnic Institute Engineers (Poly). This matchup is the oldest football rivalry in Maryland.[22] The rivalry is believed to be the second-oldest high school football rivalry in the United States between public high schools, predated only by the English High School of Boston-Boston Latin School football rivalry, which started two years earlier in 1887. The rivalry began in 1889 and the teams have met 134 times in history. In 2023, City won its 12th consecutive game in the rivalry, and now leads the series 66–62–6.[23][24]

"The Game", as this rivalry is commonly referred to, has featured legendary high school football coaches like Harry Lawrence, Bob Lumsden,[25] George Petrides,[26] and George Young. In all, 25 former players in the City-Poly game ultimately played in the National Football League (NFL), which includes the 14 NFL players City has produced.[27][28][29]

The first game in the rivalry was played on a field in northeast Baltimore's Clifton Park without spectators. Beginning in 1922, the game has been played at in large stadiums with seating capacities of 65,000 or more. From 1922 to 1996, the game was played at Baltimore Memorial Stadium, a multi-purpose stadium that was home to the Baltimore Colts and the Baltimore Ravens of the NFL and Major League Baseball's Baltimore Orioles. When the Ravens moved to M&T Bank Stadium in downtown Baltimore, the game moved to that location. The last City-Poly game at M&T Bank was played in 2017.[30] The game is now played at Hughes Stadium on the campus of Morgan State University. In October, 2024, City beat Poly 40-0 running their winning streak over their cross-town rival to 12 games.[citation needed] The Poly-City football rivalry is the oldest American football rivalry in Maryland and one of the oldest public school rivalries in the U.S.—predated by the rivalry between the Boston Latin School and the English High School of Boston.[citation needed] The rivalry began in 1889, when a team from Baltimore City College (City) met a team from the Baltimore Polytechnic Institute (Poly), and has continued annually.[citation needed] City leads the series with the record standing at 63–62–6.

Early years

Little is known of the first American style football game between the future Baltimore Polytechnic Institute (Poly) and the Baltimore City College (City) in 1889, except that a JV team from the Baltimore Manual Training School - B.M.T.S. (then only six years old, later known as B.P.I. "Engineers") met the City College "Collegians", at the newly laid out Clifton Park in northeast Baltimore and B.C.C. emerged the victor. That began the oldest football rivalry in Maryland.[citation needed] City continued to win against Poly through 1901, however in 1902, for the only time in history of the series no game was played; though, in 1931, an extra game was played to compensate.[31] Between 1903 and 1906, City won the series, but the tide turned in 1907, when the first tie in the series occurred.[32] The next year Poly scored its first victory in the rivalry.[32]

1910s and 1920s

Poly dominated the series in the 1910s. The only year of the decade that City won was 1912,[33] and between 1914 and 1917, Poly shut out City. Poly's streak continued through 1921, completing a nine-year winning streak, which City broke in 1922 with a 27–0 victory.[34]

In 1926, one of the most famous Poly-City games was played. Prior to the game, the eligibility of City's halfback, Mickey Noonen, was challenged. A committee was formed to investigate Noonen's eligibility, but Noonen's father—frustrated with the investigation—struck one of the members of the committee. The result was that Noonen was not only barred from the team, but also expelled from the Baltimore City school system.[35] In spite of Noonen's removal, the two teams met at the Baltimore Stadium with 20,000 fans in attendance. The game remained scoreless well into the fourth quarter. Finally, Poly's Harry Lawrence—who later became a coach at City—kicked a successful field goal from the 30-yard leading to a 3–0 victory over City.[citation needed]

1930s and 1940s

The 1930s ushered in a period of resurgence for the City team. Poly, which had dominated in the previous two decades, only picked up two wins in the 1930s.[33] In 1934, Harry Lawrence, who had kicked the winning field goal against City in 1926, became the head coach at his former rival.[36] Lawrence led City to a series of victories over Poly through the 1930s and early 1940s. In 1944, the game, which had been played on the Saturday following Thanksgiving, was moved to Thanksgiving Day. The change was the result of a scheduling conflict with the Army–Navy Game.[citation needed] The game remained on Thanksgiving Day for nearly 50 years.

Lumsden and Young: 1950s and 1960s

Poly won five straight games against City to open the 1950s, and 9 of the decade's 10 games, under legendary coach Bob Lumsden, for whom the school's current football stadium is named. Lumsden finished with an 11–7 record against City when he retired as head coach in 1966. He also coached 9–0 Poly to the unofficial National High School Championship Game at Miami's Orange Bowl in 1962, against the Miami High School "Stingarees", but Poly lost by a score of 14–6. The team's fortunes changed later in the decade of the 1960s, when City was coached by George Young. Young guided his teams to six wins over Poly, and an equal number of Maryland Scholastic Association championships.[37] One of Young's most memorable victories occurred on Thanksgiving Day, 1965, at Memorial Stadium, when undefeated City beat undefeated Poly 52–6.[38]

1970s–present

Poly controlled the series throughout the 1970s, and well into the 1980s. City College lost a total of unprecedented 17 consecutive games to Poly during the time of its physical renovations and academic requirements era, before again winning the 99th meeting between the two arch-rivals in 1987.[citation needed] Poly's dominance during this period is also the longest winning streak in the series. City also went on to win the historic 100th showdown a year later, before Poly got on another roll, starting with the 101st clash in 1989 winning the game 36–8. Poly won the 102nd meeting 27–0.

Baltimore City's public schools withdrew from the Maryland State Athletic Association, in 1993, and joined the Maryland Public Secondary Schools Athletic Association (MPSSAA).[39] This change meant that the football season would end earlier, forcing Poly and City to move their game from Thanksgiving Day to the first Saturday in November. Poly and City met for the 119th time in November 2007, a contest unfortenatly marred for the first time in decades by the outbreak of a large brawl outside M&T Bank Stadium after the final whistle. Poly and City met for the 120th time on November 8, 2008. Baltimore Polytechnic Institute and The Baltimore City College then met for the 121st time on November 7, 2009, with the score of 26–20. Poly and City met for the 122nd time on November 6, 2010. As of the 2018 game, City had won the prior 7 contests.

Basketball

In February 2020, ESPN ranked the boys basketball team in the top 25 in the country.[40]

Principals/Directors

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2015) |

- Dr. Richard Grady (1883–1886)

- Lt. John D. Ford, U.S.N. (1886–1890)

- Lt. William King, U.S.N. (1890–1921)

- Dr. Wilmer Dehuff (1921–1958)

- Claude Burkert (1958–1969)

- William Gerardi (1969–1980)

- Zeney P. Jacobs (1980–1984)

- Gary Thrift (1984–1985)

- John Dohler (1985–1990)

- Barbara Stricklin^ (1990–1991)

- Dr. Albert Strickland (1991–1994)

- Ian Cohen (1994–2003)

- Sharon Kanter^ (2003–2004)

- Dr. Barney Wilson (2004–2010)

- Matthew Woolston^ (2010–2011)

- Jacqueline Williams (2011–present)

^ Denotes interim director while a search for a permanent director was occurring or ongoing at the time

Notable alumni

This article's list of alumni may not follow Wikipedia's verifiability policy. (May 2020) |

Arts, literature, and entertainment

- H. L. Mencken (Henry Louis Mencken), 1896 – Writer, reporter, editor, author, columnist and commentator; "The Sun", "The Evening Sun" ("Baltimore Sunpapers"); "The Baltimore Morning Herald"; author of numerous books on American English language usage and his personal memoirs about life in Baltimore[41]

- Jae Deal – Hollywood Composer/Producer

- William J. Murray – Former student at Woodbourne Junior High School, and son of controversial atheist Madalyn Murray O'Hair, who brought case before U.S. Supreme Court about official prayers and Bible reading in public schools, 1962[42]

- Edward Wilson – British writer of spy novels[43]

- Ta-Nehisi Coates – writer

- Dashiell Hammett – writer and mystery novels author, such as "The Maltese Falcon"[44]

- Alex Scally - Guitarist of dream-pop band Beach House

Business

- Alonzo G. Decker, Jr., 1926 – former executive, chairman of the board and co-founder (with Robert Black), of nationally famous power tool and machinery company manufacturer Black and Decker Corporation, located in Towson, Maryland.[45]

Education

- John Corcoran, PhD, DHC, 1956 – logician, philosopher, mathematician, historian of logic.[46]

- Rev. Joseph Allan Panuska, S.J., 1945 – president of the University of Scranton (1982–1998), academic vice president and dean of faculties at Boston College (1979–1982), provincial of the seven state Maryland Province of the Society of Jesus (1973–1979), a biology professor and director of the Jesuit community at Georgetown University (1963–1973), and Jesuit priest.[47]

- Raynard S. Kington, MD, PhD, president of Grinell College.[48]

Government

Judicial branch

Legislative branch

- Anthony Ambridge, 1969 – (D), Councilman, District 2, Baltimore City, (1983–1996).[50]

- Thomas L. Bromwell, 1967 – (D), Maryland State Senator, District 8, Baltimore County, (1983–2002).[51]

- Andrew J. Burns Jr, 1945 – (D), Maryland State Delegate, District 43, Baltimore City (1967–1982).[52]

- Luke Clippinger, 1990 – (D), Maryland State Delegate, District 46, Baltimore City (2011–present)

- Cornell Dypski, 1950 – (D), Maryland State Delegate, District 46, Baltimore City (1987–2003).[53]

- Edward Garmatz – U.S. Representative (congressman) representing Maryland's 3rd District, (1947–1973).

- Joe Hayes (1988), member of the Alaska House of Representatives[54] (2001–2003).

- A. Wade Kach – 1966 (R) Maryland State Delegate, (1975–2014), Baltimore County Councilman, (2014–present), US Presidential Elector (1972)

- Clarence M. Mitchell, IV – (D), Maryland State Senator, District 39, Baltimore City, (1999–2003).

- Nick J. Mosby, 1997 – (D), Councilman, District 7, Baltimore City, (2011–present).[55]

- Charles E. Sydnor III, 1992 – (D), Maryland State Delegate, District 44B, Baltimore County (2015–present)

- George W. Wiland – U.S. Congressional Constituent Representative, (R), OK-1, (2001–present), U.S. Presidential Elector, (2000).

Military

- Paul J. Wiedorfer, 1939 – Won congressional Medal of Honor during World War II at the Battle of the Bulge, December 1944.

- Donald L. Gambrill, class of 1942; U.S. Army Air Corps in World War II, captain, lead pilot, 830th Bomb Sq, 485th Bomb Group (Heavy), 55 missions as B-24 pilot over Germany, Yugoslavia, Romania, Austria & Italy; Awards: Distinguished Flying Cross, Air Medal with 2 Oak Leaf Clusters, Purple Heart; KIA 10-Apr-45, buried Florence American Cemetery, Block C, Row 15, Grave 39, Florence Italy[56][full citation needed]

Sciences

- Don L. Anderson – Geophysicist, winner of the Craford Prize and the National Medal of Science.

- John Rettaliata – Fluid dynamicist, former president at the Illinois Institute of Technology.

- Robert H. Roy – mechanical engineer, dean of engineering and science at The Johns Hopkins University.

- Robert Ulanowicz (1961) – noted theoretical ecologist at the University of Maryland at College Park - Center for Environmental Science's Chesapeake Biological Laboratory

Sports

- Antonio Freeman, 1990 – Former NFL professional football player, wide receiver for the Green Bay Packers, and Philadelphia Eagles.

- Greg Kyler – Former NFL professional football player, wide receiver/defensive back in the Arena Football League[57]

- Jim Ostendarp – Former NFL professional football player and head coach at Amherst College for 33 years from 1959 to 1991.[58]

- Mike Pitts, 1978 – Former NFL professional football player, played a dozen seasons at defensive end for the Atlanta Falcons, Philadelphia Eagles, and New England Patriots.[59]

- Jack Scarbath – Former NFL professional football player, quarterback for the Washington Redskins and Pittsburgh Steelers, enshrined in College Football Hall of Fame in 1983 for All-American career at University of Maryland at College Park "Terrapins".

- Greg Schaum – Former NFL professional football player, defensive lineman with the Dallas Cowboys and New England Patriots.[60]

- Ricardo Silva, Former NFL professional football player, 2006 – former safety.

- Jack Turnbull – three-time Johns Hopkins University "Blue Jays", All-American and 1932 Olympic lacrosse player, 1936 Olympic field hockey player, and World War II, U.S. Army Air Corps fighter pilot.

- Justin Wells, current professional football player, guard in the Arena Football League. in 2006

- LaQuan Williams, 2006 – Former NFL professional football player, wide receiver for the Baltimore Ravens.[61]

- Elmer Wingate – Former NFL professional football player, defensive end for the former Baltimore Colts, All-American in both football and lacrosse at University of Maryland at College Park "Terrapins".

School songs and hymns

- Poly Fight Song - "Poly, Poly, Polytechnic!, Poly Boys Are We!" [62]

- Polytechnic Hymn, (tune: "Eternal Father, Strong to Save" - "Navy Hymn"), written by James Sagerholm, B.P.I. Class of 1946:[62]

References

Footnotes

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Baltimore Polytechnic Institute. Geographic Names Information System (GNIS). Retrieved June 22, 2012.

- ^ a b "Polytechnic Institute graduate becomes first female African-American director". WBAL-TV. May 24, 2012. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ "New Principal At Poly Makes History As First Black Woman In Position". WJZ-TV. May 24, 2012. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Baltimore Polytechnic Institute in Baltimore, MD". U.S. News and Report. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

- ^ a b c "Baltimore Polytechnic Institute". www.bpi.edu. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 19, 2015. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "The Bands - BPIWHS Combined Band Program". google.com.

- ^ a b "Baltimore Polytechnic Institute". www.bpi.edu.

- ^ Templeton (Winter 1954), p. 22-29

- ^ Thomsen (Fall 1984), p. 235-238

- ^ Templeton, Furman L. (Winter 1954). "The Admission of Negro Boys to the Baltimore Polytechnic Institute "A" Course". The Journal of Negro Education. 23 (1): 29. doi:10.2307/2293243. JSTOR 2293243.

- ^ Crockett, Sandra. "Breaking The Color Barrier at Poly in 1952". Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore, MD.

- ^ "Integration of Baltimore Polytechnic High School". Maryland Civil Rights.org. Archived from the original on October 6, 2007. Retrieved October 11, 2007.

- ^ Olson, Sherry H. Baltimore: The Building of an American City (1997) p. 368-69. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland. ISBN 0-8018-5640-X

- ^ Glazer, Aaron M. "Course Correction". Baltimore City Paper Online. Retrieved October 11, 2007.

- ^ "Academic Programs". bpi.edu. Retrieved September 15, 2019.

- ^ "The Top 500 STEM High Schools". Newsweek. November 8, 2019. Retrieved November 16, 2019.

- ^ "Athletic Team Schedules". bpi.edu. Retrieved September 15, 2019.

- ^ Stackpole, Kyle (March 16, 2019). "Poly boys basketball blows out Reservoir, becomes first program to win three straight Class 3A state titles". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved September 15, 2019.

- ^ Eisenberg, Wick (April 17, 2017). "Poly Baseball Looking To Change Baltimore City's Baseball Culture". Press Box. Retrieved September 15, 2019.

- ^ "MPSSA Football Championships Tournament History" (PDF). Maryland Public Secondary Schools Athletic Association. Retrieved September 15, 2007.

- ^ "Maryland's oldest football rivalry continues". November 2019.

- ^ Patterson (2000), p. 7.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

baltimoresun.comwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "From humble roots, Lumsden brought success to Poly's teams". October 26, 2002.

- ^ "Longtime City football coach George Petrides retires". August 5, 2015.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

pro-football-reference.comwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Baltimore Polytechnic Institute (Baltimore, MD) Alumni Pro Stats". Pro-Football-Reference.com.

- ^ "Kyle Goon: Ravens hopeful Malik Hamm has an incredible underdog story". July 26, 2023.

- ^ "M&T Bank Stadium no longer the permanent venue for Turkey Bowl, City-Poly football games". November 14, 2017.

- ^ Leonhart (1939), p. 219.

- ^ a b Leonhart (1939), p. 221.

- ^ a b Leonhart (1939), p. 229.

- ^ Leonhart (1939) p. 224.

- ^ Leonhart (1939), p. 225–226.

- ^ Leonhart (1939), p. 227.

- ^ Marudas, Kyriakos (1988). The Poly-City Game. Baltimore: Gateway Press. p. 66.

- ^ DiBlasi, Joe (November 9, 2006). "Poly-City". Word Smith Media Ventures. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved July 26, 2007.

- ^ Mills, Keith (November 8, 2007). "Poly vs. City: Tradition Time Is Here Again". Word Smith Media Ventures, LLC. Archived from the original on December 5, 2007. Retrieved November 9, 2007.

- ^ "ESPN High School Top 25". espn.com. ESPN. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "H.L. Mencken | Biography, Books, Significance, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- ^ "House school prayer vote today is largely a case of symbolism Congress reluctant to act, but fears the power of the religious right". tribunedigital-baltimoresun.

- ^ "About Edward Wilson". edwardwilson.info. Retrieved July 13, 2014.

- ^ Hamlin, Jesse (February 7, 2005). "Dashiell Hammett's legacy lies not only in his writing, but in his living -- rough, wild and on the edge". SFGATE.

- ^ "Baltimore Polytechnic Institute". bpi.edu.

- ^ "Baltimore Polytechnic Institute". bpi.edu.

- ^ "Joseph Allan Panuska". The University of Scranton: A Jesuit Institution. The University of Scranton. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- ^ "Grinnell College - A private liberal arts college in Iowa". www.grinnell.edu.

- ^ "Baltimore Polytechnic Institute". bpi.edu.

- ^ "Baltimore Polytechnic Institute". bpi.edu.

- ^ "Senate – Former Senators". Maryland State Archives. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- ^ "Andrew J. Burns Jr., delegate, dies". tribunedigital-baltimoresun.

- ^ "Baltimore Polytechnic Institute". bpi.edu.

- ^ Alaska State House 100 years - Bio Joe Hayes Retrieved July 25, 2017

- ^ "Nick Mosby, District 7: Baltimore City Council". baltimorecitycouncil.com. Archived from the original on January 8, 2015.

- ^ American Battle Monuments Commission Interment Record

- ^ "afl.com". www.afl.com. Archived from the original on October 23, 2008. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- ^ "Jim Ostendarp profile". pro-football-reference.com. Retrieved May 5, 2016.

- ^ "Mike Pitts, DE at NFL.com". National Football League. Retrieved May 5, 2012.

- ^ "HS Then & Now: For Abiamiri, Draft Day Was Just Gorgeous". Press Box Online. Archived from the original on February 7, 2012. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- ^ "Maryland State Championship". MileSplit Maryland.

- ^ a b "Poly Traditions". bpi.edu.

Sources

- Leonhart, James Chancellor (1939). One Hundred Years of the Baltimore City College. Baltimore: H.G. Roebuck & Son.

- Daneker, David C., editor (1988). 150 Years of the Baltimore City College. Baltimore: Baltimore City College Alumni Association.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Marudas, Kyriakos (1988). The City-Poly Game. Baltimore: Gateway Press.

- Templeton, Furman L. “The Admission of Negro Boys to the Baltimore Polytechnic Institute ‘A’ Course.” Journal of Negro Education 23(1) (Winter 1954)

- Thomsen, Roszel C. “The Integration of Baltimore’s Polytechnic Institute: A Reminiscence.” Maryland Historical Magazine 79 (Fall 1984)