David Berman (musician)

David Berman | |

|---|---|

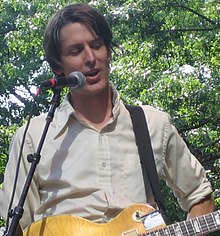

Berman performing at All Tomorrow's Parties in 2008 | |

| Born | January 4, 1967 |

| Died | August 7, 2019 (aged 52) Brooklyn, New York City, U.S. |

| Alma mater | University of Virginia University of Massachusetts Amherst |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1989–2009, 2019 |

| Spouse | Cassie Berman (1999–2018) |

| Parents |

|

| Musical career | |

| Origin | Hoboken, New Jersey |

| Genres | Country-rock |

| Instruments |

|

| Labels | |

David Cloud Berman (David Craig Berman; January 4, 1967 – August 7, 2019) was an American musician, singer, poet and cartoonist. In 1989, he founded the indie rock band Silver Jews with Stephen Malkmus and Bob Nastanovich, both of whom would later come to be known primarily for their work in the 1990s American indie rock band Pavement. He was the only constant member during the band's discography, which concluded in 2009, following the band's sixth and final album Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea (2008). He provided the distinct lyricism and, alongside Malkmus, the sparsely simple country-rock sound—which developed from initial lo-fi recordings.

He released his only book of poetry, Actual Air, in 1999. Around this time Berman began to take hard drugs; struggling with substance abuse, depression and anxiety—the latter directly influencing his career decisions. In 2003, these factors culminated in a botched suicide attempt. He then undertook rehab, engaged with Judaism and embarked on the band's first tour with his wife, Cassie Berman.

Although Berman's music and poetry were relatively successful, he experienced financial difficulties. This, along with the dissolution of his marriage, caused his return to music in 2019. He adopted a new band name, Purple Mountains, and released an eponymous debut album in July. He then intended to tour the album and thus pay off his $100,000 credit card debt. He died by suicide in August.

Despite believing his music to be unappreciated, he had acquired a reputation of being "perhaps the finest lyricist of his generation". Berman's lyrics were his creative priority, labouring over them for extended periods of time. They were abstract in nature and had become autobiographical in his later career, sung in a deep and monotone manner.

Biography

Early life

David Craig Berman[1] was born on January 4, 1967, in Williamsburg, Virginia. His father was Richard Berman, a lobbyist who represents firearm, alcohol and other industries.[2] His parents divorced when he was seven. His mother moved to Ohio, while he and his father moved to Dallas, Texas—despite Berman wishing not to.[3] He attended high school at Greenhill School in Addison, Texas, and then the University of Virginia.[2] As a teenager, he was diagnosed with depression, later discovered to be treatment-resistant and began to take drugs, smoking PCP every day of his sophomore year of college.[3][4] Berman was, by his own admission, too lazy to apply for college, and so his father's secretary applied for him.[5]

He found Dallas to be a source of musical inspiration; taking an interest in an ultra-rare Fairlight keyboard and bands like Art of Noise, Prefab Sprout, X, the Replacements, the Cure, New Order, and Echo and the Bunnymen.[6][7] He begun experiementing with poetry in high school by writing to girlfriends. He, however, considers the later line: "A cartoon lake. Wolf on skates" to be his first, true, foray.[8]

At university, Berman met fellow students Stephen Malkmus, Bob Nastanovich and James McNew.[2] Malkmus, Nastanovich and Berman frequently went to shows, brought vinyl and discussed obscure bands.[9] The quartet formed Ectoslavia, a musical exploration of experimentation and dissonance.[2] The band eventually became Berman's; Malkmus and Nastanovich were excluded by him.[9]

Origin of Silver Jews: 1989–1994

Upon graduation, the trio moved to Hoboken, New Jersey, where they shared an apartment.[10] In 1989, they adopted the moniker Silver Jews, recording discordant tapes in their living room.[2][10][a] Around this time, Berman was a security guard at New York's Whitney Museum of American Art.[10] Malkmus would occasionally act as co-writer alongside Berman.[12]

Although Berman begrudged that Silver Jews was at times viewed as a side-project to Malkmus' band Pavement, it was that connection that led to his signing with indie label Drag City, who would release all of Berman's subsequent albums.[2][13] The 'Jews' would go onto become closely linked with the label and adjacent bands. The band's first extended-plays (EP), Dime Map of the Reef and The Arizona Record, were not commercially successful but did see them garner attention, in a relative cult-like manner—Kim Gordon was an admirer and Will Oldham said it inspired him to send recordings to Drag City.[2][14][15]

Following the EPs, Berman began a masters in poetry at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.[16][17] During this time, Berman tried to get published in the American Poetry Review but was routinely rejected.[17] As of 2005, Berman's public appearances mostly consisted of poetry readings.[14]

By October 1994, the 'Jews' had enough material for their debut, Starlite Walker.[16] Malkmus and Nastanovich's involvement with Pavement meant they were unavailable for the next Silver Jews album, The Natural Bridge.[2] Pavement's success proved difficult for Berman. He resented the people who he would interact with, as a result, deeming them "cruel" and became suspicious of fame.[14] Silver Jews were a part of a "moment in underground music" of songwriters looking towards the 1970s and 80s for inspiration.[18] The line up for Silver Jews constantly changed, Berman remaining the only constant; its principal songwriter and "main creative driver".[3][5][13]

Berman's personal life, at this time, was affected by the deaths of various friends of his, which would go onto influence his songwriting.[19]

Critical acclaim and substance abuse: 1996–2001

Berman's work on the composition of The Natural Bridge in 1996 left him feeling deeply anxious. He appeared as a man "haunted by ghosts" and was hospitalized for sleep deprivation.[18] According to Oldham, the album's producer, Mark Nevers, "had sort of held Berman’s hand".[20] Although it received positive reviews in music publications—Berman having now "established himself as a world-class rock lyricist"—he chose not to tour due to a fear of performing.[2][21] After The Natural Bridge, Berman decided that he wanted Malkmus and Nastanovich involved with all following Silver Jews albums.[22]

The resulting pain helped him, alongside Malkmus, to formulate the new Silver Jews album, American Water which saw them garner critical acclaim and further attention.[2][18][23] It has been retrospectively called their breakthrough and considered a turning point in Berman's life.[24] According to Marc Hogan of Pitchfork, the opening lyrics to "Random Rules" defined the perception of his career: "Here was a man too brilliant for his own health, held captive by unseen forces".[23] Berman's drug use continued; using during studio sessions. Despite his then-personal turmoil, he did not want the album to be grim, instead joyous, like "other people['s] records".[18] They intended to tour in late 1998, but a fistfight that led to Berman's eardrum's rupturing concluded any plans.[18]

Berman's first collection of poetry, Actual Air, was released to critical acclaim in 1999 by Open City Books, which had been founded to publish the collection.[17] An independent release, the book's sales of over 20,000 copies were considered highly successful and allowed him to reach an audience beyond his music.[7][25] Although he sporadically published poems in the following years, Actual Air remained his only book of poetry. In his later years his poetry ceased, citing a lack of motivation and a partial feeling of inadequacy in comparison to younger poets.[6] In 2008, he explained why he had not published another collection: "I wait until I have something to offer...I’m waiting for myself to start writing a different kind of poetry...I’ve not found my reason for a second book yet".[26]

Around this time Berman, who no longer "[had] to work", estimated that he made $23,000 a year; In 2001, he had made $45,000 from his music.[3][27][28] In 2001, Bright Flight was released, which featured Berman's then-wife Cassie Berman—their relationship having started two years before.[29][30] The two lived in Nashville for 20 years.[31] Speaking on the local music scene, Berman found the "verbal battle between Music Row and alt-country" humorous:

Alternative country, to me, is just as ridiculously empty in a different way...All these people singing about a life they never knew—it’s really a fetishization of Depression-era country life...there’s something more authentic to me about Wal-Mart country, which speaks to the real needs of the people who listen to it, more than talking about grain whiskey stills.[32]

After being introduced to hard drugs in 1999, Berman struggled through an intense period of depression and substance abuse, using crack, heroin and methamphetamine.[2][7][31] That same year his friend Robert Bingham died of a heroin overdose.[33] His usage of crack was to the point of him considering it an addiction.[34] He unintentionally overdosed twice,[14] once, following the release party for Bright Flight.[31][35] His struggles resulted in the darker sound of Bright Flight.[30]

Attempted suicide, rehab and career progession: 2003–2008

On November 19, 2003, Berman attempted suicide in Nashville by consuming crack cocaine, alcohol and tranquillisers.[2] He wrote a short note to Cassie—the brevity of which Berman would later regret—put on his wedding suit, and went to a "crack house" he frequented. When discovered by Cassie he verbally lashed out and refused treatment. He was eventually taken to Vanderbilt University Medical Center, awaking three days later.[14]

Around a year later, he checked in for drug rehab—paid for by his father.[3] He admitted to having relapsed but said that by August 2005 he was not using.[3] His rehabilitation saw him embracing Judaism, choosing to study the Torah, and seek to be a "better person"—"easier" to Cassie and those at Drag City.[2][17][14] Five years after his botched suicide, Berman reflected and said that "Although I didn't feel lucky...I had a lot of things people would want when I tried to kill myself. [Actual Air] was only three years old, I could easily have done a follow up... I had places to go, things to do I guess".[36]

A year after Berman's rehabilitation, Silver Jews—with a lineup including Cassie, Malkmus, Nastanovich, Bobby Bare Jr., Paz Lenchantin, and William Tyler[23]—released Tanglewood Numbers.[29] Soon the band embark on their first tour.[2] Berman had been "100% sober" during Tanglewood Numbers' composition and release but this changed with touring, which made him "a daily pot smoker" to cope with the hectic nature.[31] Berman estimated that the band went on "100" tours from 2006 to 2009, the same time frame he smoked "pot".[6][31] Their first tour was documented in the 2007 film "Silver Jew".[37]

By this time, the Silver Jews had become an acclaimed indie rock band and had sold 250,000 records.[17][b] Berman and Cassie still experienced financial difficulties; Cassie worked an office job and Berman struggled to get medical insurance for the removal of a keratoconus, eventually acquiring it from the Country Music Association.[38] In 2005, Berman worked alongside his friend[36] Jeremy Blake on the art piece Sodium Fox. Inspired by Berman's poetry, he provides music and voice-overs for the narrative about him, a cowboy and a dancer.[39][40] Lines from Berman's poems that influenced the work include: "My mother was a party animal", "Frail cocktail-party hugs" and "A sweater covering the spectrum of hospital Jell-O".[40] Blake's suicide impacted Berman and his next album.[36] "Candy Jail" and "My Pillow is the Threshold" concern Blake's death.[41][42] His optical operation also affected his life and music.[42]

Following a period of downtime, the band's final album, Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea, was released, in 2008.[13] They toured the UK and Ireland before and after its release.[2][7] This period of his life saw him forego his past reservations and the band becoming more prosperous.[7][30]

His choice to tour was based upon his older age, which to him meant he was then "uncorruptable", his expanded discography and the fact that separation from his audience was infuriating.[36] He did, however, acknowledge that the intimate nature of meeting fans is "not necessarily nutritional for your creativity". Interacting with fans was, nonetheless, the highlight to him; touring was otherwise "a spiritual and intellectual deadzone".[36] Touring with Cassie, he found, eased the experience. Their dynamic while on the road was compared by Berman to that of a boss and employee.[26]

Hiatus from music: 2009–2017

Despite the band's then-present success,[4] Berman announced, on January 22, 2009, that the Silver Jews would disband, the final show to be played at Cumberland Caverns in McMinnville, Tennessee the next week. He also wrote that his intentions were to move to "screenwriting or muckraking." He closed the entry by saying, "I always said we would stop before we got bad. If I continue to record I might accidentally write the answer song to 'Shiny Happy People'".[43]

He also revealed that he was the son of lobbyist Richard Berman—in a manner that, Ari Rabin Havt, in a preface on Richard, said is "Perhaps the most scathing critique of [his] behavior".[2][44] Berman considered this his "gravest secret"; viewing his father as a "despicable man... a human molestor. An exploiter. A scoundrel. A world-historical motherfucking son of a bitch".[43] In 2005, Berman said he owed his father $10,000. Richard reportedly used this against Berman whenever they would argue.[3] Estranged for years,[13] his guilt regarding his father was the reason he retired the Silver Jews, saying:

This winter I decided that [Silver Jews] were too small of a force to ever come close to undoing a millionth of all the harm he has caused … Previously I thought through songs and poems and drawings I could find and build a refuge away from his world, but there is the matter of Justice. And I’ll tell you it’s not just a metaphor. The desire for it actually burns. It hurts. There needs to be something more.[13]

Following the band's end, Berman became a recluse, going ten years without giving an interview; his few public appearances included a poetry reading and a screening of "Trash Humpers". He spent time working on his blog, Menthol Mountains, and reading about politics, history, and religion.[2][12][30][45] He began to use the internet forum Reddit and published a book of surreal-minimal cartoons, The Portable February, in 2009.[46][47][48] Although the "hermit, solitary aspect to the way [he] live[d]" predated this time, as noted by a 2008 interview.[49]

In 2010, Berman spoke about his difficulties with a book he had been attempting to write about his father. He also revealed that HBO had expressed interest in adapting the book. A screenwriter was hired and a pilot scripted. HBO wanted to begin production but Berman cancelled it, saying he did not want to glamorize his father.[50]

A compilation of early Silver Jews entitled Early Times was released in 2012.[51] Berman worked with German artist Friedrich Kunath on the book You Owe Me a Feeling which featured paintings and poetry by Kunath and Berman, respectively.[52] After the death of his friend Dave Cloud in 2015, Berman changed his middle name from Craig to Cloud in his honor.[2] His mother died the following year, leading him to write "I Loved Being My Mother's Son", which appeared on his next album.[7]

Purple Mountains and death: 2018–2019

In 2018, Berman and Cassie separated; he lived in a room above Drag City's Chicago offices from June onwards due to lacking money to live elsewhere.[2][6] According to Berman, they "never had the kind of conflict that results in divorce" but had the "kind of need to live [their] lives without the other one". They still had the same bank account and owned a house together; Berman considered her his family, and "all [he] had".[53]

He briefly lived in Miller Beach[7] and spent winter of 2017 in Gary, Indiana.[6] At one point he had requested that a friend give him heroin. He was refused—and was, ultimately, grateful.[7] He had grown disillusioned with Judaism in relation to his isolation, recalling that his belief in god lasted from 2004 to 2010.[6][15]

In 2018, he co-produced Yonatan Gat's album Universalists.[54] In May 2019 Berman released the song "All My Happiness Is Gone", using the moniker Purple Mountains. An eponymous debut album was released in July 2019, and an accompanying tour was scheduled at the time of Berman's death.[55][56] Berman received heightened attention and rave reviews.[33] Purple Mountains was worked on with Woods and, friend, Dan Auerbach.[30] Berman and Auerbach had previously worked together in 2015.[57]

Financial difficulties, the dissolution of his marriage, and encouragement from Dan Koretzky, president of Drag City, were the impetuses for Berman's new music.[7][12][21] Berman was then living off royalties from Drag City.[58] Likely to be his most successful release, the profits from the album and tour were indicated to resolve the $100,000 of loan and credit card debt he had amassed.[7][59] His debt was a result of his drug use; in a 2005 interview, he said "I've got a credit card rotisserie system that would dazzle the ancients".[3][28] He stated that this was the only reason he intended to embark on it. He had expressed worries regarding the tour but was excited for his "solitude to end".[7][58]

He stated in June 2019 that "[f]or a long time, I've struggled very, very much with what people call treatment-resistant depression. It never goes away from me and I'm surprised I've made it this far, really, in life. There were probably 100 nights over the last 10 years where I was sure I wouldn't make it to the morning".[53] Berman died on August 7, 2019, by hanging himself in an apartment in the Park Slope neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York.[60]

Tributes

Many musicians paid tribute to Berman following his suicide: Malkmus and Nastanovich both commented on his death and later performed a show in honor of him.[61][62] Approaching Perfection: A Tribute To DC Berman is a cover album that was released two months after his death and features artists such as Dean Wareham and Adam Green.[63] Drag City released a musical tribute to Berman in the form of a cover of "The Wild Kindness", sung by Bill Callahan, Will Oldham, and Cassie Berman.[64]

The Avalanches—whom Berman collaborated with in 2012 and 2016[65][66]—Fleet Foxes, Mogwai, The Psychedelic Furs, and The Mountain Goats paid tribute on their respective albums We Will Always Love You, Shore, As the Love Continues, Made of Rain, and Dark in Here.[67][68][69][70][71]

Kunath hosted an art show he and Berman worked on, in his honor.[72] Filmmaker, Lance Bangs announced a memorial at New York's Met Breuer Museum, the former location of the Whitney.[61] The Tennessee Titans—Berman's favourite football team—displayed a message on the Jumbotron that read: "Nashville (and the world) will always love David Berman".[73] Fans shared lyrics on social media.[33] The 62nd Annual Grammy Awards' memorial reel's exclusion of Berman was criticized.[74]

Speaking of his son's death, Richard said: "Despite his difficulties, he always remained my special son. I will miss him more than he was able to realize".[75]

Artistry

Lyrics

"The storybook rhymes, the overt metaphors, the hangdog gallows humor—in many ways, Silver Jews more closely resembled classic, hard-core country than some of the famed twang-rockers of the time".[7]

The Ringer's John Lingan

Berman spent the most time of his creative process on the lyrics, feeling unable to compare to his peers, like Jack White, in musical prowess.[2] Berman's process involved him considering the audience's understanding; he juxtaposed his abstract lyricism with simple melodies and rhyme schemes.[5][26] He was self-critical and obsessed over his lyrics, to the point that Koretzky said he witnessed him work on a single line for a month.[30][27] Throughout his career, he abandoned albums as he was unable to complete the lyrics.[7]

Mark Richardson, in a 2001 Pitchfork article, and Randall Roberts of the Los Angeles Times noted his proficiency for minimalist-style compression—Richardson compared it to a haiku, Roberts noted that it was used in Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea for "universal themes of life, death and finding meaning in-between".[27][34] Influenced by his Jewish identity, Berman had a more, hopeful, plainspoken and "pedagogical" approach.[76] He found that he could "enunciate his shtick more clearly" and began to work on his lyrics for a longer period of time, to "[not stop] writing when the song just gets good enough".[77]

His songs often utilized country music tropes and tended to focus on music, nature, beauty, drugs, god, disconnection and America.[12][78] Berman thought highly of America, although did hope for a "redemption".[12][15] The opening verse to "People" was seen by Sam Hockley-Smith of Entertainment Weekly as an embrace and "entire panorama" of American history.[79] The South, a place he often mentioned, influenced The Natural Bridge and American Water; sports had a similar presence in his lyrics.[24][73][78] Politics in his songs only manifested in the form of tracks like "We Are Real".[27]

Tanglewood Numbers saw Berman's lyrics became darker and more autobiographical.[17][79] Roberts called Purple Mountains "nearly as autobiographical as a memoir".[5][34] He discussed his isolation, divorce and death, which had a particular prescience.[78][33] Berman felt that his autobiographical lyrics begun in 2001; his first three albums and book of poetry: "make-believe".[31] His fictional narratives often started relatively straightforward and then sharply became more bizarre.[42]

After garnering a greater audience from Actual Air, Berman's lyrics began to be held in a higher standard; Oldham said that Berman "[had] access to a kind of syntax I could never touch".[17][25] Kurt Vile found that Berman's lyrics impacted him in a way unlike others of his generation.[47] Associated Press's Mark Kennedy, and Kornhaber noted the influence of Berman's lyrical style and manner of delivery—Hockley-Smith said it helped "define what we understand indie rock to be"; Kaya Oakes wrote that Berman, alongside artists like Malkmus, "changed the rules of indie songwriting".[5][75][79][80]

Sound

Silver Jews' early work was defined by an ultra lo-fi aesthetic. Their work before Starlite Walker—which saw this aesthetic be dropped in favor of an experimental-oriented country-rock sound—is "regarded as the lowest fidelity recordings of the first lo-fi movement".[2][81] The lo-fi remnants were increasingly abandoned with the release of each Silver Jews album, which saw Berman's musical approach simplified and the band move further towards a country sound.[4][7][27] Purple Mountains is his most direct and conventional album, in comparison to his work with Silver Jews, although all of his discography is relatively conventional.[7][82] With Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea, Berman wanted to widen his range and so included Cassie as a prominent vocalist to "bring in a feminine point of view or a feminine voice".[49]

Their songs were often sparse and, deceptively, simple—usually three or four chords, the kind that Berman said "you might learn in beginner’s guitar lessons".[6][58][78] He usually composed songs using the basics at the end of the neck; Berman understood his musical abilities were limited.[6][7][17] For a while, he would say to himself: "if I have a purpose in life and [music] is it, why was I not given all the tools I need? Why was I not given the musical technique, the vocal chords, the all the things that a born entertainer has?".[36]

As each member wrote their own parts, Berman was solely responsible for his songwriting.[3] He would typically write the music first and then the lyrics.[83] His and Malkmus' approach to music differed. Berman explained that he viewed it as a game, whereas Malkmus saw it as a sport.[6] In 2001, Berman said that he had gone "months, sometimes years without [using his guitar]" and said his process of creating albums started in his mind and then he would "go at it every day for a few hours until the album's done".[27]

Berman's vocal delivery was notably uninflected, deadpan and brusque—his register, baritone.[7][13][17][33] During concerts, his and Cassie's performances were often symbiotic; Cassie's calm disposition providing stability to Berman's electric presence.[30] Dazed's Nick Chen noted that, in a performance documented on "Silver Jew", Berman was "a natural showman, [making] gestures with his arms that accentuate the punchiness and the hard consonants of the sing-a-long verses".[84]

Poetry

His poems and music share similar characteristics: direct delivery, observations—which are occasionally mundane and reference aspects of pop culture, such as Judas Priest, Woolite, and James Michener—and themes of Americana, absurdism, and everyday melancholy.[48][83][85] Unlike his music, his poetry did not feature rhyming.[86] He composed his poems by using the notes he had written.[6] James Tate, who Berman studied under, said that the poems were "narratives that freeze life in impossible contortions," whereas Berman called them "psychedelic soap operas".[83]

Image and self-perception

We’re not like Smog.. If you looked at all the people who said something about Will Oldham versus the Silver Jews in the 1990s, it would be a thousand to one...And that’s a good thing in the end, for me, because it’s about credibility. You can establish autonomy.[49]

David Berman, in 2008

Berman constantly considered his public image; he feared after Purple Mountains' release that he would be seen as a "sad sack".[30][58] Berman kept a note of musicians who had mentioned him in interviews, believing that his music was unappreciated.[58] Silver Jews were to him not "the band that other bands would namedrop".[49] In music and poetry, Berman felt that his peers saw him as "moonlighting".[83]

Berman was surprised that his songwriting garnered more attention than his poetry, thinking of himself as more a poet than a songwriter; however, he preferred to write music, as he found poetry offered too much freedom.[15][17] Berman likened poetry to wearing a "funny" suit and lyricism to "walking down main street", in said suit.[25]

Berman was seen as a "cult hero" due in part to his aversion to promotion and because of his work as a lyricist; considered to be "perhaps the finest of his generation".[30][33][58][c] He was, by Nastanovich's admission, "not a good self-promoter. He [was] a poet and songwriter, not a business man".[6] His initial refusal to tour generated a sense of mystique—an aversion Berman found accidental.[37][84]

Timothy Michalik of Under The Radar said that Berman embodied a simultaneous low/high-brow perception and fans, in turn, found Berman a relatable figure.[42][d] According to Berman, many fans were "encouraged that I came back from that [2003 suicide] attempt and made more records".[4] To Adam Rothband of Tiny Mix Tapes, he "felt synonymous with what he created, as if his songs and his poetry were him".[82] Arielle Angel and Nathan Goldman of Jewish Currents felt like he represented Jews "spiritually", "positionally" and, who they dubbed, "Silver Jews".[87][e] In his withdrawal, they said that Berman "[fixed] himself in Jewish tradition".[87]

Influences

Berman said that his influences consisted of Tate, Russell Edson, Kenneth Koch, Ben Katchor, Bruce Nauman, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Sherri Levine, Louise Lawler, Wallace Stevens, Charles Wright and Emily Dickinson.[31][83][49]

Discography

Silver Jews

- Starlite Walker (1994)

- The Natural Bridge (1996)

- American Water (1998)

- Bright Flight (2001)

- Tanglewood Numbers (2005)

- Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea (2008)

Purple Mountains

- Purple Mountains (2019)

Bibliography

- Actual Air (1999)

- The Portable February (2009)

Notes

- ^ On the band's early recordings, Malkmus and Nastanovich used aliases.[11]

- ^ Berman said he made $16,000 in 2004, from his first four albums.[3]

- ^ As of 2005, Silver Jews had only purchased one ad in Alternative Press in 1994, for The Arizona Record.[3]

- ^ Berman felt that to be an artist he had to "exist in a time where high and low art mix easily".[42]

- ^ Berman deemed a Silver Jew to be someone who "is a half-Jew on their dad’s side—meaning that they’ve inherited the Jewish name, but aren’t fully accepted by the religion itself".[88]

References

- ^ Rutledge, Chris (July 10, 2019). "Purple Mountains: Any Way You Hear It". American Songwriter. Archived from the original on July 10, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Cartwright, Garth (August 9, 2019). "David Berman obituary". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved March 12, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Tucker, Ashford (August 8, 2005). "Silver Jews". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Marchese, David (December 23, 2019). "David Berman of Silver Jews, Whose Music and Poetry Were a Balm". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d e Kornhaber, Spencer (August 8, 2019). "David Berman Sang the Truth". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on March 1, 2021. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Kavanagh, Adalena (January 31, 2020). "An Interview with David Berman". Believer. Archived from the original on January 21, 2021. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Lingan, John (July 10, 2019). "David Berman Returns". The Ringer. Archived from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ Cengage, Gale (December 13, 2018). "A Study Guide for David Berman's ""Snow""". Gale Cengage. ISBN 978-0-02-866569-6. Archived from the original on April 17, 2021. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ a b Bryan, Charles (2010). Pavement's Wowee Zowee. Bloomsbury. p. 27. ISBN 9780826429575.

- ^ a b c Deluca, Leo (October 19, 2018). "Silver Jews' 'American Water' Turns 20". Stereogum. Archived from the original on July 11, 2019. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- ^ Oakes, Kaya (June 9, 2009). Slanted and Enchanted: The Evolution of Indie Culture. Henry Holt and Company. p. 140. ISBN 978-1-4299-3572-2.

- ^ a b c d e Kornhaber, Spencer (August 13, 2019). "David Berman Saw the Source of American Sadness". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on January 30, 2021. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Shteamer, Hank; Newman, Jason (August 7, 2019). "Silver Jews' David Berman Dead at 52". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on August 8, 2019. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Weiden, Nick (August 2005). "The Fader 2005 interview with David Berman". The Fader. Archived from the original on March 3, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Gross, Julie (August 14, 2019). "Remembering David Berman, Leader Of Silver Jews And Purple Mountains". Louisville Eccentric Observer. Archived from the original on February 14, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ a b Larson, Sarah (August 8, 2019). "David Berman Made Us Feel Less Alone". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on August 10, 2019. Retrieved August 10, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Mason, Wyatt (October 19, 2005). "So You Want to Be a Poet, I Mean Rock Star, I Mean Poet (Published 2005)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 20, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Powell, Mike (July 30, 2017). "Silver Jews: American Water". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on August 13, 2019. Retrieved August 10, 2019.

- ^ Hyden, Steven (June 26, 2019). "Indie Hero David Berman Disappeared For A Decade — And Now He's Back". Uproxx. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ Licht, Alan (2012). Will Oldham on Bonnie Prince Billy. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 159. ISBN 0393344339.

- ^ a b Hart, Otis (August 7, 2019). "Silver Jews' David Berman Dies At 52". NPR. Archived from the original on March 13, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ Walsh, Ryan H. (October 3, 2016). "The Untold Story Of Silver Jews' The Natural Bridge: How David Berman Lost His Mind, Left Pavement Behind, And Made A Masterpiece". Stereogum. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ a b c Hogan, Marc; Sodomsky, Sam (August 9, 2019). "15 Songs That Defined David Berman's Heavy Magic". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ a b Sheffield, Rob (August 8, 2019). "Remembering David Berman's Wild Kindness". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ a b c Oakes, Kaya (June 9, 2009). Slanted and Enchanted: The Evolution of Indie Culture. Henry Holt and Company. p. 146. ISBN 978-1-4299-3572-2.

- ^ a b c Diver, Mike; Wolstenholme, Gary (June 14, 2008). "Silver Jews' David Berman in conversation". Drowned In Sound. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d e f Richardson, Mark (January 1, 2002). "Silver Jews". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on March 16, 2021. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ a b Oakes, Kaya (June 9, 2009). Slanted and Enchanted: The Evolution of Indie Culture. Henry Holt and Company. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-4299-3572-2.

- ^ a b Howe, Brian (October 21, 2005). "Silver Jews: Tanglewood Numbers". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on August 10, 2019. Retrieved August 10, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Malitz, David (June 3, 2019). "David Berman was the cult musician who went away for 10 years. What made him finally come back?". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on February 7, 2021. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Nichols, Travis (July 2017). "Actual Air in the Purple Mountains: An Interview With David Berman by Travis Nichols". Poetry Foundation. Archived from the original on February 3, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ Klosterman, Chuck (2004). Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs: A Low Culture Manifesto. Simon & Schuster. p. 155. ISBN 9780743236010.

- ^ a b c d e f Sackllah, David (August 8, 2019). "Remembering David Berman, An Artist Who Often Approached Perfection". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ a b c Roberts, Randall (August 8, 2019). "David Berman, acclaimed indie-rock singer-songwriter and poet, dies at 52". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 19, 2021. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ Wilson, Carl (July 11, 2019). "The Greatest Songwriter You've Never Heard of Is Back". Slate. Archived from the original on July 14, 2019. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Marvar, Alexandra (October 10, 2008). "Just the Gist: Silver Jews' David Berman". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

- ^ a b Riesman, Abraham (August 8, 2019). "David Berman Struggled to Feel the Joy He Brought Us". Vulture. Archived from the original on April 17, 2021. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ Currin, Grayson (August 18, 2008). "Silver Jews". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on December 13, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ Blair, Elizabeth (October 27, 2007). "Exhibit Honors Young Artist Whose Star Was Rising". NPR. Archived from the original on October 22, 2020. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

- ^ a b Hertz, Betti-Sue (2008). "Hallucinatory Vision and the Blurring of the Subject in Jeremy Blake's `Time-Based Paintings'". Animation. 3 (2). SAGE Publishing: 189–201. doi:10.1177/1746847708091894. ISSN 1746-8477. Archived from the original on May 14, 2021. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

- ^ Dollar, Steve (June 17, 2008). "David Berman Finds Comfort In His Own Head". The New York Sun. Archived from the original on October 18, 2016. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Kelly, Jennifer (June 16, 2008). "Clearer Vision: An interview With David Berman of the Silver Jews, PopMatters". PopMatters. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

- ^ a b Philips, Amy (January 23, 2009). "Silver Jews' David Berman Calls It Quits". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on June 24, 2017. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- ^ Rabin-Havt, Ari (2016). Lies, Incorporated. Anchor Books. p. 14. ISBN 9780307279590.

- ^ Sodomsky, Sam (July 12, 2019). "Purple Mountains: Purple Mountains". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on April 23, 2021. Retrieved April 23, 2021.

- ^ Lynch, Matthew (August 8, 2019). "It's Too Late Now to Hear What David Berman Was Saying". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on January 23, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ a b Beaumont-Thomas, Ben (August 8, 2019). "David Berman, acclaimed US indie songwriter, dies aged 52". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ a b Michalik, Timothy (August 9, 2019). "On the Last Day of Your Life, Don't Forget to Die: Remembering David Berman". Under The Radar. Archived from the original on January 31, 2020. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Newlin, Jimmy (June 15, 2008). "Interview: David Berman on Silver Jews's Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on May 12, 2021. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ Beller, Thomas (December 13, 2012). "A Tribute to David Berman, The Silver Jews' Genius of Free Association". Tablet. Archived from the original on December 15, 2012.

- ^ Minsker, Evan (January 8, 2015). "Silver Jews Return, Begin Working on New Music". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on December 11, 2020. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ Yoo, Noah (November 14, 2019). "Drag City Announces New Art Show Inspired by David Berman's Music". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on August 5, 2020. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ a b Khanna, Vish (June 27, 2019). "David Berman Discusses Every Song on Purple Mountains' Self-Titled New Album". Exclaim!. Archived from the original on December 20, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ Bonner, Michael (August 8, 2019). "Tributes paid to Silver Jews' David Berman, who has died aged 52". Uncut. Archived from the original on August 8, 2019. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ Sodomsky, Sam (December 12, 2018). "Silver Jews' David Berman to Release New Album in 2019 says Bob Nastanovich – Pitchfork". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on February 1, 2019. Retrieved January 31, 2019.

- ^ Sodomsky, Sam; Monroe, Jazz (May 10, 2019). "Silver Jews' David Berman Returns With First New Music in 11 Years". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on May 11, 2019. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ Camp, Zoe (November 23, 2015). "The Black Keys' Dan Auerbach's the Arcs Share "Young", Written With Silver Jews' David Berman". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Hyden, Stephen (August 8, 2019). "David Berman Was One Of Indie's Greatest Songwriters". Uproxx. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ Jenkins, Dafydd (August 6, 2019). "Purple Mountains – the eventual return of Silver Jews' David Berman". Loud and Quiet. Archived from the original on August 8, 2019. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- ^ Aniftos, Rania (August 9, 2019). "David Berman's Cause of Death Revealed". Billboard. Archived from the original on August 21, 2019. Retrieved September 11, 2019.

- ^ a b Minsker, Evan (August 8, 2019). "Silver Jews' David Berman Remembered by Stephen Malkmus, Bob Nastanovich, Bill Callahan, Kurt Vile, More". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ Ruiz, Matthew Ismael (December 18, 2019). "Stephen Malkmus and Bob Nastanovich to Perform at David Berman Tribute Show in Portland". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on March 18, 2021. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ Bloom, Madison. "Galaxie 500's Dean Wareham Covers David Berman for New Tribute Album: Listen". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on October 8, 2019. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ Strauss, Matthew (February 19, 2021). "Bill Callahan, Bonnie "Prince" Billy, and Cassie Berman Cover Silver Jews' "The Wild Kindness"". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on April 2, 2021. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ Richardson, Mark (July 8, 2016). "The Avalanches: Wildflower Album Review". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on June 18, 2020. Retrieved March 28, 2020.

- ^ Young, Alex (August 21, 2012). "New Music: The Avalanches - "A Cowboy Overflow of the Heart" (Demo)". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on May 14, 2021. Retrieved March 28, 2021.

- ^ Staff, Spin (March 18, 2020). "The Avalanches Share 'Running Red Light' Featuring Rivers Cuomo and Pink Siifu". Spin. Archived from the original on March 21, 2021. Retrieved March 28, 2021.

- ^ Strauss, Matthew (September 23, 2020). "Fleet Foxes: Shore". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ Trendell, Andrew (January 12, 2021). "Mogwai share beautiful 'Ritchie Sacramento' video and talk 'positive' new album". NME. Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ Bray, Elisa (July 30, 2020). "Album reviews: The Psychedelic Furs and Daniel Blumberg". The Independent. Archived from the original on March 1, 2021. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ Dolan, Jon (June 29, 2021). "Mountain Goats Mix Terror and Beauty on 'Dark in Here'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Yoo, Noah (November 14, 2019). "Drag City Announces New Art Show Inspired by David Berman's Music". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on August 5, 2020. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ a b Sodomsky, Sam (November 11, 2019). "David Berman Gets Tribute at Tennessee Titans Football Game". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ Clarke, Patrick (January 27, 2020). "Keith Flint, Scott Walker and more omitted from Grammys' 'In Memoriam' video". NME. Archived from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ a b Kennedy, Mark (August 9, 2019). "David Berman, founder of indie rockers Silver Jews, dies". Associated Press. Archived from the original on April 17, 2021. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ Bickford, Randy (September 10, 2008). "Silver Jews' David Berman wants his new songs to be instructive". Indy Week. Archived from the original on April 17, 2021. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ Parker, Chris (September 11, 2008). "Interview: Silver Jews". Indy Week. Archived from the original on April 17, 2021. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Johnson, Kjerstin (August 8, 2019). "Blue Arrangements: Remembering David Berman". The Ringer. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c Hockley-Smith, Sam (August 8, 2019). "David Berman was in it with the rest of us". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on August 11, 2020. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ Oakes, Kaya (June 9, 2009). Slanted and Enchanted: The Evolution of Indie Culture. Henry Holt and Company. p. 153. ISBN 978-1-4299-3572-2.

- ^ Earles, Andrew (2014). Gimme Indie Rock: 500 Essential American Underground Rock Albums 1981-1996. Voyageur Press. p. 284. ISBN 0760346488.

- ^ a b Rothband, Adam (August 9, 2019). "In Memoriam: David Berman". Tiny Mix Tapes. Archived from the original on December 3, 2019. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Writer, Academy of American Poets (February 20, 2014). "David Berman: Poems, Songs, and Psychedelic Soap Operas". Academy of American Poets. Archived from the original on August 11, 2020. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ a b Chen, Nick (August 14, 2019). "The history of the film that documented Silver Jews' earliest live shows". Dazed. Archived from the original on March 18, 2021. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ Quart, Alissa (September 12, 2019). "David Berman of Silver Jews Remembered | by Alissa Quart". The New York Review of Books. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ Clark, Chad; Toth, James (August 10, 2019). "Silver Jews' David Berman Remembered By His Peers, In His Own Words". NPR. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ a b Angel, Arielle; Goldman, Nathan (August 9, 2019). "Kaddish for David Berman". Jewish Currents. Archived from the original on December 15, 2020. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ Writer, Aquarium Drunkard (July 8, 2019). "David Berman : The Aquarium Drunkard Interview". Aquarium Drunkard. Archived from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- 1967 births

- 2019 deaths

- American male singer-songwriters

- Drag City (record label) artists

- Greenhill School alumni

- Jewish American musicians

- Jewish rock musicians

- Suicides by hanging in New York (state)

- People from Dallas County, Texas

- Poets from Virginia

- Singers from Texas

- Silver Jews members

- Songwriters from Virginia

- Songwriters from Texas

- Musicians from Charlottesville, Virginia

- University of Virginia alumni

- University of Massachusetts Amherst MFA Program for Poets & Writers alumni

- 21st-century American poets

- Berman family

- 2019 suicides

- People from Park Slope

- 21st-century American male writers