Comparative method

- For the constant comparative method by Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss, see Grounded theory.

The comparative method (in comparative linguistics) is a technique used by linguists to demonstrate genetic relationships between languages. It aims to prove that two or more historically attested languages are descended from a single proto-language by comparing lists of cognate terms. From these cognate lists, regular sound correspondences between the languages are established, and a sequence of regular sound changes can then be postulated which allows the proto-language to be reconstructed from its daughter languages. Relation is deemed certain only if a reconstruction of the common ancestor (or at least a partial reconstruction) is feasible, and if regular sound correspondences can be established with chance similarities ruled out.

Developed in the 19th century through the study of the Indo-European languages, the comparative method remains the standard by which mainstream linguists judge whether two languages are related, with alternative lexicostatistical methods widely considered to be less reliable. Criticisms of the comparative method have also arisen as a result of a number of advances in linguistic thought - including several proposed alternatives to the traditional linear model of language descent - with the result that reconstructions obtained by the comparative method are now generally treated with a degree of skepticism.

Terminology

In the present context, related has a specific meaning: two languages are genetically related if they are descended from the same ancestor language (Lyovin 1997:1-2). Thus, for example, Spanish and French are both descended from Latin. Therefore, French and Spanish are considered to belong to the same family of languages, the Romance languages (Beekes 1995:25).

Descent, in turn, is defined in terms of transmission across the generations: children learn a language from the parents' generation and are then influenced by their peers; they then transmit it to the next generation, and so on (how and why changes are introduced is a complicated, unresolved issue). A continuous chain of speakers across the centuries links Vulgar Latin to all of its modern descendants.

However, it is possible for languages to have different degrees of relatedness. English, for example, is related to both German and Russian, but is more closely related to the former than it is to the latter. The reason for this is that although all three languages share a common ancestor, Proto-Indo-European, English and German also share as a more recent common ancestor one of the daughter languages of Proto-Indo-European, Proto-Germanic, whilst Russian does not. Therefore, English and German are considered to belong to a different subgroup of the Indo-European language family, the Germanic languages, than Russian (which belongs to the Slavic subgroup) (Beekes 1995:22, 27-29). The division of related languages into sub-groups by the comparative method is accomplished by finding languages with large numbers of shared linguistic innovations from the parent language; two languages having many shared retentions from the parent language is not sufficient evidence of a sub-group.

This definition of relatedness implies that even if two languages are quite similar in their vocabularies, they are not necessarily closely related. As a result of heavy borrowing over the years from Arabic into Persian, Modern Persian in fact takes more of its vocabulary from Arabic than from its direct ancestor, Proto-Indo-Iranian (Campbell 2000:1341). But under the definition just given, Persian is considered to be descended from Proto-Indo-Iranian, and not from Arabic.

The comparative method is a method for proving relatedness in the sense just given, as well as a method for reconstructing the proto-phonemes of a languages of a family and uncovering the phonological changes the languages of a family have undergone.

Origin and development

The first known systematic attempt to prove the relationship between two languages on the basis of similarity of grammar and lexicon was made by the Hungarian János Sajnovics in 1770, when he attempted to demonstrate the relationship between Sami and Hungarian (work that was later extended to the whole Finno-Ugric language family in 1799 by his fellow countryman Samuel Gyarmathi) (Szemerényi 1996:6), but the origin of modern historical linguistics is often traced back to Sir William Jones, an English philologist living in India, who in 1782 made his famous observation:

"The Sanskrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists. There is a similar reason, though not quite so forcible, for supposing that both the Gothick and the Celtick, though blended with a very different idiom, had the same origin with the Sanskrit; and the old Persian might be added to the same family." (Jones 1786, quoted in Lehman 1967 and Szemerényi 1996:4)

Jones' insight was in conceiving of the idea of a proto-language, and consequently of the type of "family tree" model of language development (one proto-language splitting into various daughter languages, some of those then splitting again into further languages), upon which the comparative method is based.

The comparative method itself developed out of the attempts to reconstruct the proto-language which Jones had hypothesized about, known as Proto-Indo-European (PIE). The first attempt to analyse the relationships between the Indo-European languages was made by the German linguist Franz Bopp in 1816. Though he did not attempt a reconstruction, he tried to prove that Greek, Latin and Sanskrit were related by systematically demonstrating that they shared a both common structure and a common lexicon (Szemerenyi 1996:5-6).

It was the German scholar Friedrich Schlegel who in 1808 first stated the importance of using the oldest possible form of a language when trying to prove its relationships (Szemerényi 1996:7); then, in 1818, the Danish philologist Rasmus Christian Rask developed the principle of regular sound changes to explain his observations of similarities between individual words in the Germanic languages and their cognates in Greek and Latin (Szémerenyi 1996:17). It was another German, Jacob Grimm - better known for his Fairy Tales - who in Deutsche Grammatik (published 1819-37 in four volumes) first made use of something resembling the modern comparative method in attempting to show the development of the Germanic languages from a common origin, the first systematic study of diachronic language change (Szemerényi 1996:7-8).

Both Rask and Grimm were unable to explain apparent exceptions to the sound laws that they had discovered. Though the German linguist Hermann Grassmann explained one of these anomalies with the publication of his sound law in 1862 (Szemerenyi 1996:19), it was in 1875 that a Danish scholar, Karl Verner, made a methodological breakthrough when he formulated the sound law which now bears his name, and which was the first sound law to use comparative evidence to show that a phonological change in one phoneme could depend on other factors within the same word, such as the neighbouring phonemes and the position of the accent (Szemerényi 1996:20): in other words, the modern concept of conditioning environments.

Similar discoveries were made by a group of young, radical German academics at the University of Leipzig known as Junggrammatiker (usually rendered as Neogrammarians in English) in the late 1800s, leading them to conclude that all sound changes were ultimately regular, and resulting in two of them, Karl Brugmann and Hermann Osthoff, making in 1878 the famous statement that "sound laws have no exceptions" (Szemerényi 1996:21). This revolutionary idea is fundamental to the modern comparative method, since the method necessarily assumes regular correspondences between sounds in related languages, and consequently regular sound changes from the proto-language. It was this Neogrammarian Hypothesis which led to the comparative method being applied to reconstruct PIE, with Indo-European being at that time by far the most well-studied and language family. Linguists working with other families soon followed suit, and the comparative method quickly became the established method for uncovering linguistic relationships (Szemerényi 1996:6).

Application

There is no concrete set of steps to be followed in the application of the comparative method, but linguists generally agree on the basic steps, which are as follows:

Assemble cognate lists

Genetic relationship between two (or more) languages can be established if they show a number of regular correspondences in native vocabulary, which means that there is a regularly recurring match between the phonetic structure of basic words with similar meanings (Lyovin 1997:2-3). Thus, this step simply involves making lists of words which are likely cognates among the languages being compared. For example, looking at the Polynesian family (using sources such as Churchward 1959 for Tongan and Pukui & Elbert 1986 for Hawaiian; table modified from Campbell 2004 and Crowley 1992) we might come up with the following list (although in practice a real list would be much longer):

| Gloss | one | two | three | four | five | man | sea | taboo | octopus | canoe | enter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tongan | taha | ua | tolu | fā | nima | taŋata | tahi | tapu | feke | vaka | hū |

| Samoan | tasi | lua | tolu | fā | lima | taŋata | tai | tapu | feʔe | vaʔa | ulu |

| Māori | tahi | rua | toru | ɸā | rima | taŋata | tai | tapu | ɸeke | waka | uru |

| Rarotongan | taʔi | rua | toru | ʔā | rima | taŋata | tai | tapu | ʔeke | vaka | uru |

| Hawaiian | kahi | lua | kolu | hā | lima | kanaka | kai | kapu | heʔe | waʔa | ulu |

| Rapanui | -tahi | -rua | -toru | -ha | -rima | taŋata | tai | tapu | heke | vaka | uru |

Caution needs to be exercised to avoid including borrowings or false cognates in the list, which could skew or obscure the correct data (Lyovin 1997:3-5). For example, there is a similarity between English taboo [tæbu] and the five Polynesian forms. Though this may seem to be a cognate, showing that English is genetically related to the Polynesian languages, it is not, as the similarity is due to the fact that English borrowed the word from Tongan (OED 1989:"taboo, tabu, a. and n."). This problem can usually be overcome by using basic vocabulary (such as kinship terms, numbers, body parts, pronouns, and other basic terms) (Lyovin 1997:3). Nonetheless, basic vocabulary can be borrowed (Lyovin 1997:3-4). (Finnish, for example, borrowed the word for mother, äiti, from Gothic aiþei (Campbell 2004:65, 300), while Pirahã, a Muran language of South America, borrowed all its pronouns from Nhengatu (Thomason and Everett n.d.:8-12; Aikhenvald & Dixon 1999:355); likewise, English borrowed the pronouns they, them, and their(s) from Norse (OED 1989:"they, pers. pron.")

Establish correspondence sets

Once cognate lists are established, the next step is to determine the regular sound correspondences they exhibit. The notion of regular correspondence is very important here: mere phonetic similarity, as between English day and Latin dies (both with the same meaning), has no probative value (Lyovin 1997:2). English initial d- does not regularly match Latin d- (Beekes 1995:127), and whatever sporadic matches can be observed are due either to chance (as in the above example) or to borrowing (e.g. Latin diabolus and English devil, both ultimately of Greek origin) (OED 1989:"devil, n."). The Neogrammarians first emphasized this point in the late 1800s, and their motto, "sound laws have no exceptions", has remained a fundamental axiom in historical linguistics to this day.

For example, although the correspondence d- : d- (where the notation "A : B" means "A corresponds to B") in English and Latin day and dies above is not regular, English and Latin do exhibit a very regular correspondence of t- : d- (Beekes 1995:127). For example (in Latin, <c> represents /k/; dingua is an Old Latin form of the word later attested as lingua):

| English | ten | two | tow | tongue | tooth |

| Latin | decem | duo | duco | dingua | dent- |

Since a truly systematic correspondence can hardly be accidental, if we can rule out alternative possibilities like massive borrowing, the correspondence can be attributed to common descent. If there are many regular correspondence sets of this kind (the more the better), and if they add up to a sensible pattern (one that could have been produced by known types of sound change), and if some of the correspondences are non-trivial (t : t is trivial but ŋ : b is not), then common origin becomes a virtual certainty (Lyovin 1997:2-3).

Discover which sets are in complementary distribution

During the time the comparative method was being developed (late 18th to late 19th century), two major developments occurred which improved the method's effectiveness.

First, it was found that many sound changes are conditioned by a particular context. Thus for example, in both Greek and Sanskrit, an aspirated stop evolved into an unaspirated one, but only if a second aspirate occurred later on in the same word (Beekes 1995:128); this is Grassmann's law, known to the Sanskrit grammarian Pāṇini (Sag 1974, Janda & Joseph 1989) and promulgated as a historical discovery by Hermann Grassmann.

Second, it was found that sometimes sound changes occurred in contexts that were later lost. For instance, in Sanskrit velars (k-like sounds) were replaced by palatals (ch-like sounds) whenever the following vowel was *i or *e (the asterisk means that the sound is inferred rather than historically documented). Subsequent to this change, all instances of *e were replaced by a (or, more accurately, earlier *e, *o, and *a merged as a). The situation would have been unreconstructable, had not the original distribution of e and a been recoverable from the evidence of other Indo-European languages (Beekes 1995:60-61). Thus, for instance, Latin que, and, preserves the original e vowel that caused the consonant shift in Sanskrit:

| 1. | *ke | Pre-Sanskrit and |

| 2. | *ce | Velars replaced by palatals before *i and *e |

| 3. | ca | *e becomes a |

Ca is the attested Sanskrit form for and. This finding was made independently by several scholars during the 1870s.

In the Dravidian languages of Telugu, Tamil and Malayalam, velar plosives in Proto-Dravidian have been replaced by the corresponding palatal if the velar plosive is followed by /i/, /iː/, /e/ or /eː/. However, this change is absent in Kannada and few other languages in the family. For example, Proto-Dravidian *kedi becomes Tamil chedi, but Kannada gida (Krishnamurti 2003:128-129).

Verner's Law, discovered by Karl Verner in about 1875, is a similar case: the voicing of consonants in Germanic languages underwent a change that was determined by the position of the old Indo-European accent. Following the change, the accent shifted across the board to initial position (Beekes 1995:130-131). Verner solved the puzzle by comparing the Germanic voicing pattern with data from Greek and Sanskrit accent.

This stage of the comparative method, therefore, involves examining the correspondence sets discovered in step 2 and seeing which of them apply only in certain contexts. If two (or more) sets involve identical or similar sounds, and apply in complementary distribution, then the sets can be assumed to reflect a single original phoneme. This is because "some sound changes, particularly conditioned sound changes, can result in a proto-sound being associated with more than one correspondence set" (Campbell 2004:136).

To take another example, when we examine the Romance languages, descended from Latin, we find two different correspondence sets which both involve k:

| Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | French | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | k | k | k | k |

| 2. | k | k | k | ʃ |

What we do in this situation is try to see if the two sets occur in complementary distribution (in which case they reflect a single proto-phoneme) or if both occur in identical environments (in which case they must both reflect separate proto-phonemes). In this case, we discover that French ʃ only occurs before a in the other languages (which becomes ɛ in French), while French k occurs elsewhere. Both sets 1 and 2 can therefore be assumed to reflect a single proto-phoneme (in this case *k, spelled <c>) (Campbell 2004:26).

A more complex case involves consonant clusters in Proto-Algonquian, which have been notoriously difficult to reconstruct. The Algonquianist Leonard Bloomfield used the reflexes of the clusters in four of the daughter languages of Proto-Algonquian to come up with the following correspondence sets (although the clusters are shown here ending in -k, this also generally applies to clusters ending in any of the plosives; <š> and <č> are Americanist symbols for /ʃ/ and /ʧ/; table modified after that in Campbell 2004:141):

| Ojibwe | Meskwaki | Plains Cree | Menomini | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | kk | hk | hk | hk |

| 2. | kk | hk | sk | hk |

| 3. | sk | hk | sk | čk |

| 4. | šk | šk | sk | sk |

| 5. | sk | šk | hk | hk |

Although all five correspondence sets overlap with one another in various places, they are not in complementary distribution, and so Bloomfield recognized that a different cluster must be reconstructed for each set (his reconstructions were, respectively, *hk, *xk, *čk, *šk, and çk; the modern reconstructions for these clusters are *hk, *tk, čk, šk, and rk, respectively, and two more clusters, reconstructed as *ʔk and ɬk, are recognized (Bloomfield 1925; Picard 1984; Goddard 1994a and b)).

Reconstruct proto-phonemes

This step tends to be much more subjective than the previous ones. A linguist here has to rely mostly on their general intuitions about what types of sound changes are likely and which are unlikely. For example, the voicing of voiceless plosives between vowels is an extremely common sound change, occurring in languages all over the world, whilst the devoicing of voiced plosives between vowels is extremely uncommon. Therefore, if a linguist were comparing two languages with a correspondence of -t- : -d- between vowels, they would reconstruct the proto-phoneme as being *-t-, and assume that it became voiced to -d- in the second language (unless they had a very good reason not to).

Sometimes, sound changes occur that are extremely unexpected. The Proto-Indo-European word for two, for example, is reconstructed as *duwō, which is reflected in Classical Armenian as erku. Several other cognates demonstrate that the change *d- → erk- in the history of Armenian was a regular one (Szemerényi 1996:28; citing Szemerényi 1960:96). Similarly, in Bearlake, a dialect of the Athabaskan language of Slavey, there has been a sound change of Proto-Athabaskan *ts → Bearlake kʷ (Campbell 1997). It is very unlikey that *d- changed directly into erk- and *ts into kʷ, but instead they must have gone through several intermediate steps to arrive at the later forms. The lesson here is that with enough sound changes, a given sound can change into just about any other sound. This is why it is not phonetic similarity which matters when utilizing the comparative method, but regular sound correspondences (Lyovin 1997:2).

Another assumption used in determining a proto-phoneme is that our reconstruction should ideally involve as few sound changes as possible to arrive at the modern reflexes in the daughter languages. In other words, unless there is persuasive evidence to the contrary, we should reconstruct for a proto-phoneme whatever value is the most common reflex in the daughter languages. For example, in the Algonquian languages, we find the following correspondence set ([1]; Goddard 1974):

| Ojibwe | Mi'kmaq | Cree | Munsee | Blackfoot | Arapaho |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m | m | m | m | m | b |

The simplest reconstruction for this set would be either *m or *b. Both *m → b and *b → m (where "*A → B" means "*A becomes B") are conceivable sound changes, so the principle of reconstructing "likely" changes over "unlikely" ones is not useful here. Instead, because the reflex of this proto-phoneme is m in five of the languages compared here, and b in only one of them, if we reconstruct *b then we need to assume five separate changes of *b → m, whereas if we reconstruct *m, we only need to assume a single change of *m → b in one language in the family. Since we are working on the assumption that our reconstructions should require the fewest number of changes possible to arrive at the modern reflexes, we would reconstruct *m here.

Examine the reconstructed system typologically

In the final step, the linguist takes all the proto-phonemes they have reconstructed using steps 1-4, and checks to see how the system fits with what is currently known about typological constraints. For example, if the reconstructed phonemes fit together in the following system, the linguist would be suspicious, because languages generally (though not always) tend to maintain symmetry in their phonemic inventories:

| p | t | k |

|---|---|---|

| b | ||

| n | ŋ | |

| l |

In this reconstructed system, there is only one voiced plosive, *b, and although there is an alveolar and a velar nasal, *n and *ŋ, there is no corresponding labial nasal. In this case, we would have to return to step 4 and reevaluate our earlier conclusions. In this case, we would try to figure out if there is any evidence to suggest that what we earlier reconstructed as *b is in fact *m, or evidence that what we earlier reconstructed as *n and *ŋ are in fact *d and *g.

Even a symmetrical system can be typologically suspicious. For example, the Proto-Indo-European plosive inventory, as traditionally reconstructed (Beekes 1995:124), is as follows:

| Labials | Dentals | Velars | Labiovelars | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voiceless | p | t | k | kʷ |

| Voiced | (b) | d | g | gʷ |

| Voiced aspirated | bʱ | dʱ | gʱ | gʷʱ |

Since the mid-20th century, a number of linguists have argued that this system is, at best, very suspicious typologically (Szemerényi 1996:143). They state that it is extremely unlikely, or maybe even impossible, for a language to have a voiced aspirated (breathy voice) series without a corresponding voiceless aspirated series. These linguists therefore argue, on typological grounds, that we need to reevaluate the traditional reconstruction of Proto-Indo-European. A potential solution was provided by Thomas Gamkrelidze and Vyacheslav V. Ivanov, who argued that the series traditionally reconstructed as plain voiced should in fact be reconstructed as glottalized — either implosive (ɓ, ɗ, ɠ) or ejective (pʼ, tʼ, kʼ). The plain voiceless and voiced aspirated series would thus be seen as just voiceless and voiced, with aspiration being a non-distinctive quality of both (Beekes 1995:109-113). This example of the application of linguistic typology to linguistic reconstruction has become known as the Glottalic Theory. It has a large number of proponents but is not generally accepted (Szemerényi 1996:151-152).

The reconstruction of proto-sounds and their historical transformations enables us to proceed further: we can compare grammatical morphemes (word-forming affixes and inflectional endings), patterns of declension and conjugation, and so on. The full reconstruction of an unrecorded protolanguage can never be complete (for example, proto-syntax is far more elusive than phonology or morphology, and all elements of linguistic structure undergo inevitable erosion and gradual loss or replacement over time), but a consistent partial reconstruction can and must be attempted as proof of genetic relationship.

Criticism

A number of difficulties with aspects related to the method are now recognized (Lyovin 1997:4-5, 7-8). However, the comparative method is still seen as being a valuable tool in comparative linugistics, and linguists continue to use it widely; other proposed approaches to determining linguistic relationships and reconstructing proto-languages, such as glottochronology and mass lexical comparison, are considered flawed and unreliable by most linguists (Campbell 2004:347-348; Lyovin 1997:8; Trask 1996), but in contrast to previous generations of historical linguists, present-day linguists recognize that results obtained with the comparative method are to be viewed skeptically. Fox (1997:141-2), for example, concludes:

"The Comparative Method as such is not, in fact, historical; it provides evidence of linguistic relationships to which we may give a historical interpretation. ...[Our increased knowledge about the historical processes involved] has probably made historical linguists less prone to equate the idealizations required by the method with historical reality. ...Provided we keep [the interpretation of the results and the method itself] apart, the Comparative Method can continue to be used in the reconstruction of earlier stages of languages."

Neogrammarian Hypothesis

The first weakness of the comparative method is the Neogrammarians' fundamental assumption that "sound laws have no exceptions." This assumption is problematic even on theoretical grounds: the very fact that different languages evolved according to different sound-change laws seems to indicate a degree of arbitrariness in language evolution. Moreover, once one accepts that sound changes may be conditioned by context according to rather complicated rules, one opens the door for "laws" that may affect only a few words, or even a single word; which is logically equivalent to admitting exceptions to the broader laws. This problem has led some critics to a radically opposite position, summarized by the maxim "each word has its own history" (Szemerényi 1996:23).

Borrowings, areal diffusion and random mutations

Even the Neogrammarians recognized that, apart from the general sound change laws, languages are also subject to borrowings from other languages and other sporadic changes (such as irregular inflections, compounding, and abbreviation) that affect one word at a time, or small subsets of words.

While borrowed words should be excluded from the analysis, on the grounds that they are not genetic by definition, they do add noise to the data, and thus may hide systematic laws or distort their analysis. Moreover, there is the danger of circular reasoning — namely, of assuming that a word has been borrowed solely because it does not fit the current assumptions about the regular sound laws.

Attempts to apply the comparative method to languages which have been affected by the process of areal diffusion can also be problematic. This is, in essence, a subtle form of borrowing, which can take place when a significant number of speakers of one language have some competence in another, possibly unrelated language. This may lead to the languages acquiring phonological characteristics from one another, sometimes even without the conscious borrowing of lexical or morphological forms, with the result that the two languages may end up appearing to be genetically related when in fact they are not. It is also possible that two or more unrelated languages may appear to be related as the result of them all individually undergoing areal diffusion from a third unrelated language (Aikhenvald & Dixon 2001:2-3).

The other exceptions to the sound laws are a more serious problem, because they occur in generic language transmission. One example of such a sporadic change, with no apparent logical reason, is the Spanish word for word, palabra. By regular sound changes from the Latin parabŏla, it should have become parabla, but the r and l changed places by sporadic metathesis) (Campbell 2004:39).

In principle, as those sporadic changes accumulate, they will increasingly obscure the systematic sound laws, and eventually prevent the recognition of the genetic relationship between languages, or lead to incorrect reconstructions of proto-languages and incorrect family trees.

Analogy

A source of sporadic changes that was recognized by the Neogrammarians themselves was analogy, in which a word is sporadically changed to be closer to another word in the lexicon which is perceived as being somehow related to it. For example, the Russian word for nine, by regular sound changes from Proto-Slavic, should have been /nʲevʲatʲ/, but is in fact /dʲevʲatʲ/. It is believed that the initial nʲ- changed to dʲ- due to influence of the word for "ten" in Russian, /dʲesʲatʲ/ (Beekes 1995:79).

Gradual application

More recently, William Labov and other linguists who have studied contemporary language changes in detail have discovered that even a systematic sound change is at first applied in an unsystematic fashion, with the percentage of its occurrence in a person's speech dependent on various social factors (Beekes 1995:55; Szemerényi 1996:3). Often the sound change begins to affect some words in a language, and then gradually spreads to others, a process known as lexical diffusion. These observations considerably weaken the Neogrammarians axiom that "sound laws have no exceptions."

Problems with the Tree Model

Another weakness of the comparative method is its reliance on the Tree Model (German Stammbaum) (Lyovin 1997:7-8). In this model, daughter languages are seen as branching out from the proto-language, gradually growing more and more distant from the proto-language through accumulated phonological, morpho-syntactic, and lexical changes; and possibly splitting into further daughter languages. This model is usually represented by upside-down tree-like diagrams. For example, here is a diagram of the Uto-Aztecan family of languages, spoken throughout the southern and western United States and Mexico (diagram based on Mithun 1999 and Campbell 1997):

Wave Model

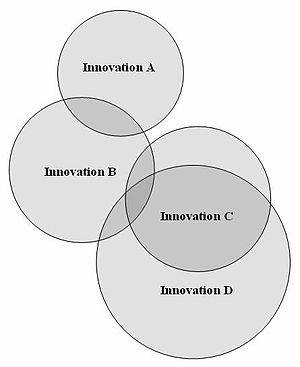

Since languages change gradually, there are long periods in which different dialects of a language, as they evolve into separate languages, remain in contact with one another and influence each other. Therefore, the Tree Model does not reflect the reality of how languages change, as even once they are completely separated, languages which are near to one another will continue to influence each other, often sharing grammatical, phonological, and lexical innovations. A change in one language of a family will often spread to neighboring languages; and multiple waves of change may partially overlap like waves on the surface of a pond, across language and dialect boundaries, each with its own randomly delimited range (Fox 1995:129). The following diagram illustrates this conception of language change, called the Wave Model:

This is a serious challenge to the comparative method, which is entirely based on the assumption that each language has a single "genetic" parent, and hence that the genetic relationship between two languages is due to their descent from a common ancestor.

Punctuated-Equilibrium

Dixon (1997) has proposed a similar model to the Wave Model, the Punctuated-Equilibrium Model (borrowed from the Punctuated Equilibrium theory of evolutionary biology). In essence, the Punctuated-Equilibrium Model of language relationships suggests that most languages, for most of human history, were in a state of "equilibrium" with their neighbors: they changed relatively slowly, and exchanged areal features (including phonological features, morphological patterns, and loanwords) with one another. After hundreds or thousands of years of a state of equilibrium like this, such features would have diffused throughout the linguistic area, making all of the languages broadly similar in many respects. However, at various times, Dixon proposes, there were events which "punctuated" this state of equilibrium (including natural disasters like volcanic eruptions and floods, invasions into the area by new cultures, the expansion into a new area of the people speaking the language, or the invention of a new, life-changing technology), causing the languages to enter a brief period of very rapid change, where they would quickly split into many new daughter languages. It is only in such situations, according to Dixon, that the Tree Model is applicable; once these daughter languages begin to settle into a new period of equilibrium with their new neighbors, they will quickly acquire the common linguistic features of that area, and in time their genetic origin will be entirely obscured. This Punctuated-Equilibrium Model has received a great deal of attention from linguists, and many are inclined to accept the model as accurate[citation needed]. If this model does represent the way languages change, then the Tree Model - and the comparative method, which is necessarily based on it - can only be applied in limited cases.

Non-uniformity of the proto-language

Another assumption implicit in the methodology of the comparative method is that the proto-language is uniform. This is problematic, as even in extremely small language communities there are always dialect differences, whether based on area, gender, class, or other factors (the Pirahã language of Brazil is spoken by only several hundred people, but has at least two different dialects, one spoken by men and one by women, for example (Aikhenvald & Dixon 1999:354; Ladefoged 2003:14). Therefore, the single proto-language reconstructed by the comparative method is, in all likelihood, a language which never existed.

Creoles

Another potential problem for the comparative method is the phenomenon of creole language formation, where a new language is formed from a complicated combination of two languages that are not closely related. The Papiamentu language, spoken in the Caribbean, is a notable example (Holm 1989:312). In these events, the new language may end up with a lexicon and phonology which is derived from both parent languages, in varying proportions; while the grammar (morphology and syntax) is partly inherited, and partly the result of local innovation. Often function words from one of the parent languages are inherited, but used for a completely different function in the creole (Holm 1989).

Creole formation seems to be a fairly common phenomenon. Dozens of such events have been documented in the last 500 years, in the wake of European colonial expansion, and many more must have happened along the fringes of past empires. While the comparative method may be able to detect the existence of a genetic relation between the creole and the parent languages (or between two creoles with shared parents), the reconstructed "proto-language" is likely to be a thoroughly artificial construct.

Subjectivity of the reconstruction

While the identification of systematic sound correspondences between known languages is fairly objective, the reconstruction of their common ancestral language is inherently subjective. In the Proto-Algonquian example above, the choice of *m as the parent phoneme is only likely, not certain. It is conceivable that a Proto-Algonquian language with *b in those positions split into two branches, one which preserved *b and one which changed it to *m instead; and while the first branch only developed into Arapaho, the second spread out wider and developed into all the other Algonquian tribes. (Such dramatic asymmetries in the growth of different branches of the same tree are in fact common; contrast for example the Romance and Celtic branches of Indo-European.) It is also possible that the nearest common ancestor of the Algonquian languages used some other sound instead, such as *p, which eventually mutated to *b in one branch and to *m in the other.

Since the reconstruction of a proto-language involves many of these choices, the probability of making a wrong choice is very high. That is, any reconstructed proto-language is almost certainly incorrect; it is an artificial construct that is accepted by convention, not by rigorous proof. These hidden errors take their toll when two reconstructed proto-languages are compared in order to build a larger family tree.

See also

References

- Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. and R. M. W. Dixon (eds.) (1999). The Amazonian Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ———— (eds.) (2001). Areal Diffusion and Genetic Inheritance: Problems in Comparative Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Beekes, Robert S. P. (1995). Comparative Indo-European Linguistics. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Bloomfield, Leonard (1925). "On the Sound System of Central Algonquian." Language 1:130-56.

- Campbell, George L. (2000). Compendium of the World's Languages (2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

- Campbell, Lyle (1997). American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ———— (2004). Historical Linguistics: An Introduction (2nd ed.). Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Churchward, C. Maxwell. (1959). Tongan Dictionary. Tonga: Government Printing Office.

- Comrie, Bernard (ed.) (1990). The World's Major Languages. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Crowley, Terry (1992). An Introduction to Historical Linguistics (2nd ed.). Auckland: Oxford University Press.

- Dixon, R. M. W. (1997). The Rise and Fall of Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fox, Anthony (1995). Linguistic Reconstruction: An Introduction to Theory and Method. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Goddard, Ives (1974). "An Outline of the Historical Phonology of Arapaho and Atsina." International Journal of American Linguistics 40:102-16.

- ———— (1994a). "A New Look for Algonquian." Paper presented at the Comparative Linguistics Workship, University of Pittsburgh, April 9.

- ———— (1994b). "The West-to-East Cline in Algonquian Dialectology." Actes du Vingt-Cinquième Congrès des Algonquibustes, ed. William Cowan: 187-211. Ottawa: Carleton University.

- Holm, John (1989). Pidgins and Creoles. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Janda, Richard D. & Brian D. Joseph (1989). "In Further Defence of a Non-Phonological Account for Sanskrit Root-Initial Aspiration Alternations". Proceedings of the Fifth Eastern States Conference on Linguistics: 246-260. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State University. Available online at http://www.ling.ohio-state.edu/~bjoseph/publications/1989aspiration.pdf

- Jones, Sir William (1786). "The Third Anniversary Discourse, on the Hindus." In Lehman, W. P. (ed.) (1967). A Reader in Nineteenth Century Historical Indo-European Linguistics. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Available online at http://www.utexas.edu/cola/centers/lrc/iedocctr/ie-docs/lehmann/reader/chapterone.html

- Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju (2003). The Dravidian Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ladefoged, Peter (2003). Phonetic Data Analysis: An Introduction to Fieldwork and Instrumental Techniques. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Lyovin, Anatole V. (1997). An Introduction to the Languages of the World. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc. ISBN 0-19-508116-1.

- Mithun, Marianne (1999). The Languages of Native North America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- OED (1989). The Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pederson, Holger (1962). The Discovery of Language. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Picard, Marc (1984). "On the Naturalness of Algonquian ɬ." International Journal of American Linguistics 50:424-37.

- Pukui, Mary Kawena (1986). Hawaiian Dictionary. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press. ISBN 0-8248-0703-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Sag, Ivan. A. (1974) "The Grassmann's Law Ordering Pseudoparadox," Linguistic Inquiry 5: 591-607.

- Szemerényi, Oswald J. L. (1960). Studies in the Indo-European System of Numerals. Heidelberg: C. Winter.

- ———— (1996). Introduction to Indo-European Linguistics (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Thomason, Sarah G. and Daniel L. Everett (n.d.). Pronoun Borrowing. Available online at http://ling.man.ac.uk/Info/staff/DE/pronborr.pdf

- Trask, R. L. (1996). Historical Linguistics. New York: Oxford University Press.

- "Vocabulary Words in the Algonquian Language Family" from Native Languages of the Americas