Medical abortion

| Background | |

|---|---|

| Abortion type | Medical |

| First use | United States 1979 (carboprost), West Germany 1981 (sulprostone), Japan 1984 (gemeprost), France 1988 (mifepristone), United States 1988 (misoprostol) |

| Gestation | 3–24+ weeks |

| Usage | |

| Medical abortions as a percentage of all abortions | |

| France | 64% (2016) |

| Sweden | 92% (2016) |

| UK: Eng. & Wales | 62% (2016) |

| UK: Scotland | 83% (2016) |

| United States | 39% (2017) |

| Infobox references | |

| Combination of | |

|---|---|

| Mifepristone | Progesterone receptor modulator |

| Misoprostol | Prostaglandin |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | Mifegymiso,[1] Medabon Combipack |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

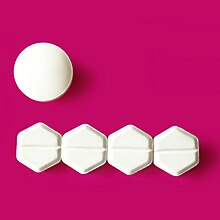

A medical abortion, also known as medication abortion, occurs when medically-prescribed drugs (medication) are used to bring about an abortion. A typical regimen consists of a combination of medications, with mifepristone followed by misoprostol being the most common abortifacient regimen.[4] Mifepristone followed by misoprostol for abortion is considered both safe and effective throughout a range of gestational ages.[5] When mifepristone is not available, misoprostol alone may be used. In addition to mifepristone/misoprostol, other medications may be used depending on availability and patient-specific considerations.

Medical procedures to physically induce abortion that do not primarily use medication are generally referred to as surgical abortion.

Medical use

Through 12 weeks' gestation

For medical abortion prior to 12 weeks' gestation, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends mifepristone 200 mg by mouth followed 1–2 days later by misoprostol 800 mcg inside the cheek, vaginally, or under the tongue; misoprostol may be repeated to maximize success.[6] The success rate of mifepristone followed by one dose of misoprostol through 10 weeks' pregnancy is 96.6%.[7] Those who took misoprostol less than 24 hours after mifepristone had higher failures rates compared to women who waited 1–2 days.[8] The National Abortion Federation (NAF) also recommends a mifepristone and misoprostol combination regimen. For medication abortion up to 10 weeks of pregnancy, 200 mg mifepristone is taken followed in 24 to 48 hours by 800 mcg misoprostol. For pregnancies after 9 weeks, repeating the dose of misoprostol makes the treatment more effective.[9] From 10 to 11 weeks of pregnancy, NAF protocol includes a routine second dose of misoprostol 800 mcg four hours after the first dose.[10]

If mifepristone is not available, the WHO recommends misoprostol 800 mcg inside the cheek, under the tongue, or in the vagina.[6] The success rate of misoprostol alone for first trimester abortion is 78%.[11]

Though not a first line choice, a methotrexate/misoprostol combination regimen is appropriate. Methotrexate is given either orally or intramuscularly, followed by vaginal misoprostol 3–5 days later.[12] This is an appropriate option for gestations through 63 days. Per the WHO, a methotrexate-misoprostol regimen can also be used;[13] but is not recommended as methotrexate may be teratogenic to the fetus in cases of incomplete abortion. However, this combination is considered more effective than misoprostol alone.[14]

After 12 weeks' gestation

WHO recommends mifepristone 200 mg by mouth (orally) followed 1–2 days later by misoprostol 400 mcg under the tongue, inside the cheek, or in the vagina.[6] Misoprostol may be taken in repeated doses every 3 hours until successful abortion is achieved, the mean time to abortion after starting misoprostol is 6–8 hours, and approximately 94% will abort within 24 hours after starting misoprostol.[15] When mifepristone is not available, misoprostol may still be used though the mean time to abortion after starting misoprostol will be extended compared to regimens using mifepristone followed by misoprostol.[16]

Self-administered medical abortion

Self-administered medical abortion is available to women who prefer to take the abortion drug without direct medical supervision, in contrast to provider-administered medical abortion where the woman takes the abortion drug in the presence of a trained healthcare provider. Evidence from clinical trials indicates self-administered medical abortion may be as effective as provider-administered abortion but the safety aspects remain uncertain.[17]

Medical abortion was introduced as a service where a person visits a health center in-person due to FDA requirements that the first abortion pill, mifepristone, be dispensed directly by a health provider and not by prescription.[18] Other models exist to safely increase patient access to medication abortion. These models were expanded during the COVID-19 pandemic.[19][20] Women report high levels of satisfaction with telehealth abortion services.[21][22] Telehealth options for people in the United States seeking medication abortion include Aid Access, Hey Jane, and Plan C Pills.

Clinic-to-clinic

In this model, a provider communicates with a patient located at another site using clinic-to-clinic videoconferencing to provide medication abortion. This was introduced by Planned Parenthood of the Heartland in Iowa to allow a patient at one health facility to communicate via secure video with a health provider at another facility.[23] This model has expanded to other Planned Parenthoods in multiple states as well other clinics providing abortion care.[23]

Direct-to-patient

The direct-to-patient model allows for medication abortion to be provided without an in-person clinic visit. Instead of an in-person clinic visit, the patient receives counseling and instruction from the abortion provider via videoconference. The patient can be at any location, including their home. The medications necessary for the abortion are mailed directly to the patient. This is a model, called TelAbortion or no-test medication abortion (formerly no-touch medication abortion), being piloted and studied by Gynuity Health Projects, with special approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).[24] This model has been shown to be safe, effective, efficient, and satisfactory.[19][25][26] Complete abortion can be confirmed via telephone-based assessment.[27]

Contraindications

Contraindications to mifepristone are inherited porphyria, chronic adrenal failure, and ectopic pregnancy.[28][29] Some consider an intrauterine device in place to be a contraindication as well.[29] A previous allergic reaction to mifepristone or misoprostol is also a contraindication.[28]

Many studies excluded women with severe medical problems such as heart and liver disease or severe anemia.[29] Caution is required in a range of circumstances including:[28]

- long-term corticosteroid use;

- bleeding disorder;

- severe anemia

In some cases, it may be appropriate to refer people with preexisting medical conditions to a hospital-based abortion provider.[30]

Adverse effects

Symptoms that require immediate medical attention:[31]

- Heavy bleeding (enough blood to soak through four sanitary pads in 2 hours)

- Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, fever for more than 24 hours after taking mifepristone

- Fever of 38 °C (100.4 °F) or higher for more than 4 hours

Most women will have cramping and bleeding heavier than a menstrual period.[29] Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, dizziness, and fever/chills are also common. Misoprostol taken vaginally tends to have fewer gastrointestinal side effects. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications such as ibuprofen reduce pain with medication abortion.

Although medical abortion is associated with more bleeding than surgical abortion, overall bleeding for the two methods is minimal and not clinically different. In a large-scale prospective trial published in 1992 of more than 16,000 women undergoing medical abortion using mifepristone with varying doses of gemeprost or sulprostone, only 0.1% had hemorrhage requiring a blood transfusion. It is often advised to contact a health care provider if there is bleeding to such degree that more than two pads are soaked per hour for two consecutive hours.

Management of bleeding

Vaginal bleeding generally diminishes gradually over about two weeks after a medical abortion, but in individual cases spotting can last up to 45 days.[28] If the woman is well, neither prolonged bleeding nor the presence of tissue in the uterus (as detected by obstetric ultrasonography) is an indication for surgical intervention (that is, vacuum aspiration or dilation and curettage). Remaining products of conception will be expelled during subsequent vaginal bleeding. Still, surgical intervention may be carried out on the woman's request, if the bleeding is heavy or prolonged, or causes anemia, or if there is evidence of endometritis.

Complications

Complications following medical abortion with mifepristone and misprostol under 10 weeks' pregnancy are rare; according to two large reviews, bleeding requiring a blood transfusion occurred in 0.03–0.6% of women and serious infection in 0.01–0.5%.[7][8] Because infection is rare after medication abortion, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), The Society of Family Planning (SFP), and NAF do not recommend use of routine antibiotics.[32][12] A few rare cases of deaths from clostridial toxic shock syndrome have occurred following medical abortions.[33]

Pharmacology

Mifepristone blocks the hormone progesterone,[34][35] causing the lining of the uterus to thin and preventing the embryo from staying implanted and growing. Methotrexate, which is sometimes used instead of mifepristone, stops the cytotrophoblastic tissue from growing and becoming a functional placenta.[36] Misoprostol, a synthetic prostaglandin, causes the uterus to contract and expel the embryo through the vagina.[37]

Frequency

| Country | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Italy | 17% in 2015[38] |

| Spain | 19% in 2015[39] |

| Belgium | 22% in 2011[40] |

| Netherlands | 22% in 2015[41] |

| Germany | 23% in 2016[42] |

| United States | 39% in 2017[43] |

| England and Wales | 62% in 2016[44] |

| France | 64% in 2016[45] |

| Iceland | 67% in 2015[46] |

| Denmark | 70% in 2015[46] |

| Portugal | 71% in 2015[47] |

| Switzerland | 72% in 2016[48] |

| Scotland | 83% in 2016[49] |

| Norway | 87% in 2016[50] |

| Sweden | 92% in 2016[51] |

| Finland | 96% in 2015[52] |

A Guttmacher Institute survey of abortion providers estimated that early medical abortions accounted for 31% of all nonhospital abortions and 45% of nonhospital abortions before 9 weeks' gestation in the United States in 2014.[53][54] A subsequent survey also by the Guttmacher Institute estimated that medication abortions accounted for 39% of all abortions in the US that year, a 25% increase from 2014.[43]

At Planned Parenthood clinics in the United States, medical abortions accounted for 32% of first trimester abortions in 2008,[55] 35% of all abortions in 2010 and 43% of all abortions in 2014.[56]

History

Medical abortion became an alternative method of abortion with the availability of prostaglandin analogs in the 1970s and the antiprogestogen mifepristone (also known as RU-486)[57] in the 1980s.[14][58][59] Mifepristone was initially approved in China and France (1988); in 2000, the United States Food and Drug Association approved mifepristone followed by misoprostol for abortion through 49 days.[60] In 2016, the United States FDA updated mifepristone's label to support usage through 70 days' gestation.[61]

Society and culture

The legal and political setting should support people's access to evidence-based medically approved care, including medical abortion.[62][63]

Medical abortion regimens using mifepristone in combination with a prostaglandin analog are the most common methods used to induce second-trimester abortions in Canada, most of Europe, China and India;[59] in contrast to the United States where 96% of second-trimester abortions are performed surgically by dilation and evacuation.[64]

"Reversal" controversy

Some anti-abortion groups claim that the abortifacient effect of mifepristone can be reversed by administering progesterone before the person takes misoprostol.[65][66] At this time there is no scientifically rigorous evidence that the effects of mifepristone can be reversed this way.[67][68] Even so, several states in the US require providers of non-surgical abortion who use mifepristone to tell patients that reversal is an option.[69] In 2019, researchers initiated a small trial of the so-called "reversal" regimen using mifepristone followed by progesterone or placebo.[70][71] The study was halted after 12 women enrolled and three experienced severe vaginal bleeding. The results raise serious safety concerns about using mifepristone without follow-up misoprostol.[68]

Cost

In the United States in 2009, the typical price charged for a medical abortion up to 9 weeks' gestation was $490, four percent higher than the $470 typical price charged for a surgical abortion at 10 weeks' gestation.[72] In the United States in 2008, 57% of women who had abortions paid for them out of pocket.[73]

In April 2013, the Australian government commenced an evaluation process to decide whether to list mifepristone (RU486) and misoprostol on the country's Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS). If the listing is approved by the Health Minister Tanya Plibersek and the federal government, the drugs will become more accessible due to a dramatic reduction in retail price—the cost would be reduced from between AU$300 and AU$800, to AU$12 (subsidised rate for concession card holders) or AU$35.[74]

On 30 June 2013, the Australian Minister for Health, the Hon. Tanya Plibersek MP, announced that the Australian Government had approved the listing of mifepristone and misoprostol on the PBS for medical termination in early pregnancy consistent with the recommendation of the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC).[75] These listings on the PBS commenced on 1 August 2013.[76]

References

- ^ "Mifegymiso Product Monograph" (PDF). Health Canada.

- ^ "Medabon - Combipack of Mifepristone 200 mg tablet and Misoprostol 4 x 0.2 mg vaginal tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). February 3, 2020. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- ^ https://www.ema.europa.eu/documents/psusa/mifepristone/misoprostol-list-nationally-authorised-medicinal-products-psusa/00010378/202005_en.pdf

- ^ Medical management of abortion. World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland. January 30, 2019. p. 24. ISBN 978-9241550406. OCLC 1084549520.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Safe abortion: technical and policy guidance for health systems-2nd ed. Italy: WHO. 2012. p. 42. ISBN 9789241548434.

- ^ a b c Medical management of abortion. World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland. 2018. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-9241550406. OCLC 1084549520.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b Chen MJ, Creinin MD (July 2015). "Mifepristone With Buccal Misoprostol for Medical Abortion: A Systematic Review". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 126 (1): 12–21. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000897. PMID 26241251. S2CID 20800109.

- ^ a b Raymond EG, Shannon C, Weaver MA, Winikoff B (January 2013). "First-trimester medical abortion with mifepristone 200 mg and misoprostol: a systematic review". Contraception. 87 (1): 26–37. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2012.06.011. PMID 22898359.

- ^ Kapp N, Eckersberger E, Lavelanet A, Rodriguez MI (February 2019). "Medical abortion in the late first trimester: a systematic review". Contraception. 99 (2): 77–86. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2018.11.002. PMC 6367561. PMID 30444970.

- ^ prochoice. "Clinical Policy Guidelines". National Abortion Federation. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

- ^ Raymond EG, Harrison MS, Weaver MA (January 2019). "Efficacy of Misoprostol Alone for First-Trimester Medical Abortion: A Systematic Review". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 133 (1): 137–147. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003017. PMC 6309472. PMID 30531568.

- ^ a b "Clinical Policy Guidelines".

- ^ "Women's Health".

- ^ a b Creinin MD, Danielsson KG (2009). "Medical abortion in early pregnancy". In Paul M, Lichtenberg ES, Borgatta L, Grimes DA, Stubblefield PG, Creinin MD (eds.). Management of unintended and abnormal pregnancy : comprehensive abortion care. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 111–134. ISBN 978-1-4051-7696-5.

- ^ Borgatta L, Kapp N (July 2011). "Clinical guidelines. Labor induction abortion in the second trimester". Contraception. 84 (1): 4–18. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.02.005. PMID 21664506.

- ^ Perritt JB, Burke A, Edelman AB (September 2013). "Interruption of nonviable pregnancies of 24-28 weeks' gestation using medical methods: release date June 2013 SFP guideline #20133". Contraception. 88 (3): 341–9. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2013.05.001. PMID 23756114.

- ^ Gambir K, Kim C, Necastro KA, Ganatra B, Ngo TD (March 2020). "Self-administered versus provider-administered medical abortion". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3: CD013181. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013181.pub2. PMC 7062143. PMID 32150279.

- ^ "Mifepristone Prescribing Information" (PDF). FDA.

- ^ a b Belluck P. "Abortion by Telemedicine: A Growing Option as Access to Clinics Wanes". The New York Times. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ "Medication Abortion and Telemedicine: Innovations and Barriers During the COVID-19 Emergency". KFF. June 8, 2020. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- ^ Ireland S, Belton S, Doran F (March 2020). "'I didn't feel judged': exploring women's access to telemedicine abortion in rural Australia". Journal of Primary Health Care. 12 (1): 49–56. doi:10.1071/HC19050. PMID 32223850.

- ^ Ehrenreich K, Kaller S, Raifman S, Grossman D (September 2019). "Women's Experiences Using Telemedicine to Attend Abortion Information Visits in Utah: A Qualitative Study". Women's Health Issues. 29 (5): 407–413. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2019.04.009. PMID 31109883.

- ^ a b "Improving Access to Abortion via Telehealth". Guttmacher Institute. May 7, 2019. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- ^ "Telabortion Project". Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ^ Raymond E, Chong E, Winikoff B, Platais I, Mary M, Lotarevich T, et al. (September 2019). "TelAbortion: evaluation of a direct to patient telemedicine abortion service in the United States". Contraception. 100 (3): 173–177. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2019.05.013. PMID 31170384.

- ^ "New Multi-State Study Shows Telemedicine Abortion Is as Safe and Effective as In-Person Care". www.plannedparenthood.org. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ^ Chen MJ, Rounds KM, Creinin MD, Cansino C, Hou MY (August 2016). "Comparing office and telephone follow-up after medical abortion". Contraception. 94 (2): 122–6. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2016.04.007. PMID 27101901.

- ^ a b c d International Consensus Conference on Non-surgical (Medical) Abortion in Early First Trimester on Issues Related to Regimens and Service Delivery (2006). Frequently asked clinical questions about medical abortion (PDF). Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-159484-4.

- ^ a b c d "Medical management of first-trimester abortion". Contraception. 89 (3). American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Society of Family Planning: 148–61. March 2014. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2014.01.016. PMID 24795934.

- ^ Guiahi M, Davis A (December 2012). "First-trimester abortion in women with medical conditions: release date October 2012 SFP guideline #20122". Contraception. 86 (6): 622–30. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2012.09.001. PMID 23039921.

- ^ "Mifepristone Prescribing Information" (PDF). FDA.

- ^ Achilles SL, Reeves MF (April 2011). "Prevention of infection after induced abortion: release date October 2010: SFP guideline 20102". Contraception. 83 (4): 295–309. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2010.11.006. PMID 21397086.

- ^ Murray S, Wooltorton E (August 2005). "Septic shock after medical abortions with mifepristone (Mifeprex, RU 486) and misoprostol". CMAJ. 173 (5): 485. doi:10.1503/cmaj.050980. PMC 1188182. PMID 16093445.

- ^ "The Science Behind the "Abortion Pill"".

- ^ Medical management of first trimester abortion, Society of Family Planning Clinical Guideline, Contraception 89(2014) 148-161

- ^ "Methotrexate".

- ^ "Misoprostol".

- ^ "Relazione Ministro Salute attuazione Legge 194/78 tutela sociale maternità e interruzione volontaria di gravidanza - dati definitivi 2014 e 2015 [Ministry of Health report implementation Act 194/78 social protection maternity and voluntary interruption of pregnancy - definitive data 2014 and 2015]". Rome: Ministero della Salute [Ministry of Health]. December 15, 2016. Table 25 - IVG and type of intervention, 2015: mifepristone + mifepristone+prostaglandin + prostaglandin = 17%.

- ^ "Interrupción Voluntaria del Embarazo; Datos definitivos correspondientes al año 2015 (Voluntary interruption of pregnancy; final data for 2015" (PDF). Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad, Politica Social e Igualdad (Ministry of Health and Social Policy). December 30, 2016. Table G.15: 17,916 (sum of the greater of mifepristone or prostaglandin abortions by gestation period) / 94,188 (total abortions) = 19.0%.

- ^ Commission Nationale d'Evaluation des Interruptions de Grossesse (August 27, 2012). "Rapport Bisannuel 2010-2011". Brussels: Commission Nationale d'Evaluation des Interruptions de Grossesse. prostaglandin 0.40% + mifepristone 21.23% = 21.63% medical abortions

- ^ "Jaarrapportage 2015 van de Wet afbreking zwangerschap [Annual Report 2015 of the Discontinuation of Pregnancy Act]". Utrecht, Netherlands: Inspectie voor de Gezondheidszorg (IGZ) [Health Care Inspectorate], Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport (VWS) [Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport]. February 9, 2017.

- ^ "Schwangerschaftsabbrüche 2016 (Abortions 2016)" (PDF). Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt (Federal Statistical Office), Germany. March 9, 2017. 20.237% Mifegyne + 3.021% Medikamentöser Abbruch = 23.257% medical abortions

- ^ a b Jones RK, Witwer EM, Jerman J (2019). "Abortion Incidence and Service Availability in the United States, 2017" (Document). doi:10.1363/2019.30760.

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help) - ^ "Abortion statistics, England and Wales: 2016" (PDF). London: Department of Health, United Kingdom. May 30, 2017.

Medical abortion accounted for 72% of abortions under 10 weeks' gestation—in England and Wales in 2016. - ^ Vilain A (June 26, 2017). "211 900 interruptions volontaires de grossesse en 2016 (211,900 voluntary terminations of pregnancies in 2016)" (PDF). Paris: DREES (Direction de la Recherche, des Études, de l'Évaluation et des Statistiques), Ministère de la Santé (Ministry of Health), France.

- ^ a b Heino A, Gissler M (March 7, 2017). "Pohjoismaiset raskaudenkeskeytykset 2015 (Induced abortions in the Nordic countries 2015)" (PDF). Helsinki: Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos (National Institute for Health and Welfare), Finland. ISSN 1798-0887. Appendix table 6. Drug-induced abortions in Nordic countries 1993–2015, %

- ^ "Relatório dos Registos das Interrupções da Gravidez - Dados de 2015 [Report of the Interruptions of Pregnancy - Data of 2015]". Lisbon: Divisão de Saúde Sexual, Reprodutiva, Infantil e Juvenil [Division of Sexual, Reproductive, Child and Juvenile Health], Direção de Serviços de Prevenção da Doença e Promoção da Saúde [Directorate of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Services], Direção-Geral da Saúde (DGS) [Directorate-General for Health]. September 20, 2016.

- ^ "Interruptions de grossesse en Suisse en 2016 (Abortions in Switzerland 2016)". Neuchâtel: Office of Federal Statistics, Switzerland. June 13, 2017.

- ^ "Termination of pregnancy statistics, year ending December 2016" (PDF). Edinburgh: Information Services Division (ISD), NHS National Services Scotland. May 30, 2017.

Medical abortions accounted for 89% of abortions before 9 weeks' gestation in Scotland in 2016. - ^ Løkeland M, Mjaatvedt AG, Akerkar R, Pedersen Y, Bøyum B, Hornæs MT, Ebbing M (March 8, 2017). "Rapport om svangerskapsavbrot for 2016" [Report on pregnancy terminations for 2016] (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Divisjon for epidemiologi (Division of Epidemiology), Nasjonalt Folkehelseinstitutt (Norwegian Institute of Public Health), Norway. ISSN 1891-6392.

Medical abortions accounted for 90% of abortions before 9 weeks' gestation in Norway in 2016. - ^ Öman M, Gottvall K (May 10, 2017). "Statistik om aborter 2016 (Statistics on abortions in 2016)" (PDF). Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen (National Board of Health and Welfare), Sweden.

Medical abortions accounted for 94% of abortions before 9 weeks' gestation in Sweden in 2016. - ^ Heino A, Gissler M (October 20, 2016). "Raskaudenkeskeytykset 2015 (Induced abortions 2015)" (PDF). Helsinki: Suomen virallinen tilasto (Official Statistics of Finland), Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos (National Institute for Health and Welfare), Finland.

- ^ Jones RK, Jerman J (March 2017). "Abortion Incidence and Service Availability In the United States, 2014". Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 49 (1): 17–27. doi:10.1363/psrh.12015. PMC 5487028. PMID 28094905.

96% of all abortions performed in nonhospital facilities × 31% early medical abortions of all nonhospital abortions = 30% early medical abortions of all abortions; 97% of nonhospital medical abortions used mifepristone and misoprostol—3% used methotrexate and misoprostol, or misoprostol alone—in the United States in 2014. - ^ Jatlaoui TC, Ewing A, Mandel MG, Simmons KB, Suchdev DB, Jamieson DJ, Pazol K (November 2016). "Abortion Surveillance - United States, 2013" (PDF). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries. 65 (12): 1–44. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss6512a1. PMID 27880751.

Medical abortions accounted for 22.2% of abortions—and 32.8% of abortions at ≤8 weeks' gestation—in the United States in 2013 that were voluntarily reported to the CDC by 43 reporting areas (excluding California, Florida, Hawaii, Illinois, Louisiana, Maryland, New Hampshire, Tennessee, and Wyoming). - ^ Fjerstad M, Trussell J, Sivin I, Lichtenberg ES, Cullins V (July 2009). "Rates of serious infection after changes in regimens for medical abortion". The New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (2): 145–51. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0809146. PMC 3568698. PMID 19587339.

Allday E (July 9, 2009). "Change cuts infections linked to abortion pill". San Francisco Chronicle. p. A1. - ^ Mindock C (October 31, 2016). "Abortion Pill Statistics: Medication Pregnancy Termination Rivals Surgery Rates In The United States". International Business Times. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ^ Rowan A (2015). "Prosecuting Women for Self-Inducing Abortion: Counterproductive and Lacking Compassion". Guttmacher Policy Review. 18 (3): 70–76. Retrieved October 12, 2015.

- ^ Kulier R, Kapp N, Gülmezoglu AM, Hofmeyr GJ, Cheng L, Campana A (November 2011). "Medical methods for first trimester abortion". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (11): CD002855. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002855.pub4. PMC 7144729. PMID 22071804.

- ^ a b Kapp N, von Hertzen H (2009). "Medical methods to induce abortion in the second trimester". In Paul M, Lichtenberg ES, Borgatta L, Grimes DA, Stubblefield PG, Creinin MD (eds.). Management of unintended and abnormal pregnancy : comprehensive abortion care. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 178–192. ISBN 978-1-4051-7696-5.

- ^ Creinin MD, Chen MJ (August 2016). "Medical abortion reporting of efficacy: the MARE guidelines". Contraception. 94 (2): 97–103. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2016.04.013. PMID 27129936.

- ^ "Highlights of Prescribing Information, Mifeprex" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved October 10, 2019.

- ^ Medical management of abortion. WHO. 2018. p. 24. ISBN 978-9241550406.

- ^ "Human Rights and Health". World Health Organization Newsroom. September 21, 2019.

- ^ Hammond C, Chasen ST (2009). "Dilation and evacuation". In Paul M, Lichtenberg ES, Borgatta L, Grimes DA, Stubblefield PG, Creinin MD (eds.). Management of unintended and abnormal pregnancy : comprehensive abortion care. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 178–192. ISBN 978-1-4051-7696-5.

- ^ "As controversial 'abortion reversal' laws increase, researcher says new data shows protocol can work". Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ^ "California Board of Nursing Sanctions Unproven Abortion 'Reversal' (Updated) - Rewire". Rewire. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- ^ Bhatti KZ, Nguyen AT, Stuart GS (March 2018). "Medical abortion reversal: science and politics meet". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 218 (3): 315.e1–315.e6. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2017.11.555. PMID 29141197. S2CID 205373684.

- ^ a b "Safety Problems Lead To Early End For Study Of 'Abortion Pill Reversal'". NPR.org. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Counseling and Waiting Periods for Abortion". March 14, 2016.

- ^ "Controversial 'Abortion Reversal' Regimen is Put to the Test".

- ^ "There's no proof "abortion reversals" are real. This study could end the debate". April 17, 2019.

- ^ Jones RK, Kooistra K (March 2011). "Abortion incidence and access to services in the United States, 2008" (PDF). Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 43 (1): 41–50. doi:10.1363/4304111. PMID 21388504.

Stein R (January 11, 2011). "Decline in U.S. abortion rate stalls". The Washington Post. p. A3. - ^ Jones RK, Finer LB, Singh S (May 4, 2010). "Characteristics of U.S. abortion patients, 2008" (PDF). New York: Guttmacher Institute.

Mathews AW (May 4, 2010). "Most women pay for their own abortions". The Wall Street Journal. - ^ Peterson K (April 30, 2013). "Abortion drugs closer to being subsidised but some states still lag". The Conversation Australia. The Conversation Media Group. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ^ Australian Government. "March 2013 PBAC Outcomes - Positive Recommendations". PBS: The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- ^ NPS Medicine Wise (2013). "Mifepristone (Mifepristone Linepharma) followed by misoprostol (GyMiso) for medical termination of pregnancy of up to 49 days' gestation". RADAR Review. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

External links

- WHO Scientific Group on Medical Methods for Termination of Pregnancy (December 1997). Medical methods for termination of pregnancy. Technical Report Series, No. 871. Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-120871-0. WARNING: LINK GIVES ONLY THE FIRST PAGE OF THE REPORT; THE REST IS LISTED AS "OUT OF PRINT"

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (November 23, 2011). The care of women requesting induced abortion. Evidence-based clinical guideline number 7 (PDF) (3rd rev. ed.). London: RCOG Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 29, 2012.

- ICMA (2013). "ICMA Information Package on Medical Abortion". Chișinău, Moldova: International Consortium for Medical Abortion (ICMA). Archived from the original on July 10, 2010.

- The official protocol of the clinical trial of the "reversal" regimen is here: Clinical trial number NCT03774745 for "Blocking Mifepristone Action With Progesterone" at ClinicalTrials.gov