Caddyshack II

| Caddyshack II | |

|---|---|

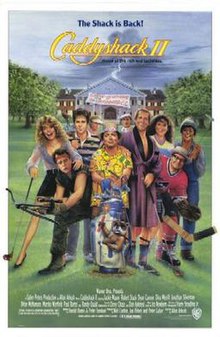

Theatrical release poster by Carl Ramsey | |

| Directed by | Allan Arkush |

| Screenplay by | |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Harry Stradling Jr. |

| Edited by | Bernard Gribble |

| Music by | Ira Newborn |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 98 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $20 million[1] |

| Box office | $11.8 million[2] |

Caddyshack II is a 1988 American sports comedy film and a sequel to the 1980 film Caddyshack. Directed by Allan Arkush, Caddyshack II stars Jackie Mason, Dan Aykroyd, Robert Stack, Dyan Cannon, Randy Quaid, Chevy Chase, Jonathan Silverman, and Jessica Lundy. The writing of the film is officially credited to Harold Ramis (who co-wrote and directed the original Caddyshack) and PJ Torokvei, although the first-draft script by Ramis and Torokvei was rewritten by other uncredited writers.

The sequel was panned by critics and is considered one of the worst sequels of all time.[3] The theme song, Kenny Loggins' "Nobody's Fool", was a chart success, hitting #8 on the Billboard Hot 100.

Plot

Kate Hartounian is the daughter of a wealthy and widowed real estate developer of Armenian and Jewish descent. Eager to improve her lot in life, she makes friends with Miffy Young, a snooty WASP girl, who encourages her and her father to join their country club.

Kate and her father, Jack, apply for membership at Bushwood, the club from the first movie. Jack is a self-made millionaire, yet remains self-effacing, friendly, and generous despite his wealth. His crude personality and eccentric clothing foil him on many occasions.

When the current members meet Jack, who builds low-income housing in more upscale neighborhoods, his application to join is rejected. The rejection stems from his oafish personality and an earlier confrontation with Bushwood President (and Miffy's father) Chandler Young's wife. The glamorous Cynthia Young had tried unsuccessfully to persuade Jack to build his housing complex away from her neighborhood, but her less-than-subtle snobbery leads Jack to chase Cynthia with a bulldozer. It's actions like these that build a divide between Jack and Kate.

Ty Webb returns, this time as the club's majority owner, and while he admires Jack, he prefers to stay out of the way of the club's day-to-day operations.

The elitist members of Bushwood reject Jack's membership application and pull strings to suspend his housing operation. In retaliation, Jack buys Bushwood's stock from Ty and turns it into an amusement park. Chandler, incensed at the thought of a mere "nouveau-riche" individual getting the better of him, hires Captain Tom Everett (who code-names Chandler "Mrs. Esterhaus"), a shell-shocked mercenary operating out of a lunch wagon, to "discourage" Jack from building any more structures on Bushwood property. The bumbling Everett decides to use explosive golf balls to do this.

Meanwhile, Chandler uses his lawyers and connections to shut down Jack's housing construction site. Webb suggests that the dispute should be resolved like gentlemen, by facing each other in a golf match. If Chandler wins, Jack loses his construction site and the country club, and if Jack wins, he keeps Bushwood and the housing project.

Despite Jack's poor performance early in the match, with luck, he ties the match before the final hole. However, during the hole, Jack is faced with a 50-foot putt, while Chandler faces a simple two-foot putt. Using the advice given to him by Webb before the match, Jack manages to use spiritual chanting and the adage "be the ball" to sink the nearly impossible putt. Chandler needs to sink the easy two-foot putt to tie the match.

Meanwhile, Everett, who foolishly shoots himself in the buttocks with a poison dart, fails to eliminate Jack as a gopher steals his explosive ball. The mischievous gopher replaces Chandler's ball with the explosive ball, and as his family encouragingly crowds around him as he taps in his final swing, the ball bursts and Jack wins the match.

Though Kate is embarrassed by her father's actions, she is still loyal to him, as evidenced when she commiserates to Miffy, who suggests that she change her last name from Hartounian to Hart. Bewildered at the thought of turning her back on her family name, Kate turns her back on Miffy and makes up with her father.

Cast

- Jackie Mason as Jack Hartounian

- Robert Stack as Chandler Young

- Randy Quaid as Peter Blunt

- Dan Aykroyd as Captain Tom Everett

- Chevy Chase as Ty Webb

- Jessica Lundy as Kate Hartounian

- Dyan Cannon as Elizabeth Pearce

- Jonathan Silverman as Harry

- Dina Merrill as Cynthia Young

- Marsha Warfield as Royette Tyler

- Brian McNamara as Todd Young

- Chynna Phillips as Mary Frances 'Miffy' Young

- Paul Bartel as Mr. Jamison

- Anthony Mockus Sr. as Mr. Pierpont

- Bibi Osterwald as Mrs. Pierpont

- Frank Welker as the voice of the Gopher

- James Veeley as Captain

- Ben Hartigan as Naked Man

Pre-Production

The original Caddyshack was a box-office success, making $60 million worldwide on a budget of $4.8 million. Warner Brothers therefore set about to make a sequel. As originally planned, Caddyshack II would have reunited Rodney Dangerfield (one of the stars of the original Caddyshack) with the director Alan Metter, who had worked with Dangerfield in the comedy film Back to School (1986). Dangerfield, who made $35,000.00 for Caddyshack, asked for $7 million - $5 million of which to be paid in advance – for reprising his Al Czervic role in Caddyshack II. Needing a big comedy for the summer of 1988, Warner Brothers agreed to Dangerfield’s demands, and paid Chevy Chase a seven-figure sum to reprise his role of Ty Webb from the original Caddyshack (albeit via a glorified cameo).[3]

Jon Peters, executive producer of Caddyshack, would produce the sequel with Peter Guber and Neil Canton. The studio invited Caddyshack director Harold Ramis, who co-wrote that film with Brian Doyle-Murray and Douglas Kenney, to write the sequel. (Neither Doyle-Murray nor Kenney were involved in the sequel; Caddyshack producer/co-writer Kenney died in August 1980, a month after that film's release.)

Ramis later described Caddyshack II, which he co-wrote with his Second City Television colleague PJ Torokvei, as "terrible."[4] In an interview with The A.V. Club in 1999, Ramis said that,

...with Caddyshack II, the studio begged me. They said, "Hey, we've got a great idea: 'The Shack is Back!'" And I said "No, I don't think so." But they said that Rodney really wanted to do it, and we could build it around Rodney. Rodney said, "Come on, do it." Then the classic argument came up which says that if you don't do it, someone will, and it will be really bad. So I worked on a script with my partner Peter Torokvei, consulting with Rodney all the time. Then Rodney got into a fight with the studio and backed out. We had some success with Back to School, which I produced and wrote, and we were working with the same director, Alan Metter. When Rodney pulled out, I pulled out, and then they fired Alan and got someone else. I got a call from [co-producer] Jon Peters saying, "Come with us to New York; we're going to see Jackie Mason!" I said, "Ooh, don't do this. Why don't we let it die?" And he said, "No, it'll be great." But I didn't go, and they got other writers to finish it. I tried to take my name off that one, but they said if I took my name off, it would come out in the trades and I would hurt the film."[4]

Ramis was later quoted as saying that Dangerfield was the only one who expressed an interest in doing a sequel in the first place. Ted Knight had died two years earlier, Bill Murray was not interested in reprising his role as Carl the greenskeeper, and he said Chevy Chase had "already moved on", although Chase did eventually agree to appear.

Ramis worked on the first draft of Caddyshack II in the summer of 1987 with Torokvei. Rodney Dangerfield did not like the script and requested rewrites. Growing disillusioned with the project, Dangerfield reportedly tried to force Warner Brothers to release him from his contract by demanding additional royalties and final-cut rights. In October 1987, less than a month before Caddyshack II was scheduled to begin filming and with $2 million already spent by the studio on pre-production, Dangerfield dropped out of the project because he felt it would not be successful.[5] Warner Brothers sued Dangerfield for breach of contract.[6] Early in the hearings, the studio settled with Dangerfield for an undisclosed amount.[3]

The project was put on hold while Warner Brothers looked for a new director, eventually landing upon Allan Arkush. A former protégé of Roger Corman and collaborator of Joe Dante, Arkush directed several motion pictures (including the 1979 cult hit Rock 'n' Roll High School) before becoming a prolific director of episodic television, with credits including L.A. Law, St. Elsewhere, and Moonlighting. Arkush was keen to get back into directing films, later recalling, "I had a really successful run on television. Moonlighting was a big deal, I was doing L.A. Law, working on pilots and I had a deal with Warner Brothers to direct and they said, “Well, there’s another National Lampoon movie.” National Lampoon Goes to College and I thought, “That sounds like a good idea.” They couldn’t get it bought. So they asked, “How would you like to make Caddyshack II?”[7]

After the offer was made, Arkush rented and watched the original Caddyshack and signed on to direct the sequel. He was not aware at the time of the litigation between the studio and Rodney Dangerfield.

Production

It was only after agreeing to direct Caddyshack II that Allan Arkush realized how much trouble the project was in: production began in late 1987 and Warner Brothers still insisted upon a summer 1988 release, meaning only half a year for principal photography and post-production. Adding to this difficulty was the fact the project was in no shape to begin filming. Arkush later claimed, “The more I got into it, the more I realized that they didn’t have a script that was in any kind of shape, they didn’t have Bill Murray and now they didn’t have Rodney Dangerfield.” Arkush likened his assignment “to hopping onto a moving ship barreling full steam ahead.”[3]

Screenwriters Jeffrey Price and Peter S. Seaman, who scripted Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), were brought in to overhaul Ramis and Torokvei’s script (although they would ultimately receive no official credit for doing so). With Rodney Dangerfield out of the picture, the screenplay replaced Al Czervic with Jack Hartounian, a new character to be played by Jackie Mason - like Dangerfield, a Jewish-American Borsch Belt stand-up comedian. After witnessing Mason's one-man comedy act on Broadway at the insistence of producer Jon Peters, Allan Arkush was concerned about the comedian's suitability for the film: “The thing that occurred to me was that [Mason] didn’t connect with the audience in any sort of personal way. That’s not necessarily a good thing for someone who’s supposed to be your lead. At least when Rodney says, ‘I get no respect,’ there’s an empathy that he evokes from the audience.”[3] Arkush also stated, "[Mason] is a very funny joke machine and you laugh yourself silly. I needed a comedian who was equally an actor. I went to the producer Jon Peters and told him my fears. He was so convinced that Jackie was a brilliant comedian and could pull it off. Jon looked me in the eye and said, “Don’t turn a Go picture into a development deal.” I should have walked away."[7] Mason's casting in Caddyshack II was publicly announced by Daily Variety on November 17, 1987.

Chevy Chase was the only cast member from the original Caddyshack to reprise his role (and would publicly announce later that he regretted doing so). Bill Murray refused to reprise his Carl Spackler role, opting to make Scrooged (1988) instead. Murray's Saturday Night Live and Ghostbusters colleague Dan Aykroyd signed on in Murray's place, portraying a mercenary/survivalist hired to kill the gopher plaguing the golf course. Although playing new characters in the sequel, Jackie Mason, Robert Stack, Dan Aykroyd, and Jonathan Silverman play roles that are analogous to those played by Dangerfield, Knight, Murray, and Michael O'Keefe in the first film. Sam Kinison, who had appeared alongside Dangerfield in Back to School, was originally intended for Randy Quaid's role, but left the production when Dangerfield dropped out.

Caddyshack II began filming on January 18, 1988, at the Rolling Hills Country Club in Davie, Florida (where Caddyshack had been filmed just under a decade prior). Despite working on the set with a golf pro, Mason could not make a convincing golf swing; he also couldn’t remember his lines, had no chemistry with this onscreen love interest (played by Dyan Cannon) and his gorging at the craft services table meant the wardrobe department had to keep letting out his pants. Aykroyd angered the producers by insisting on playing his role with a high-pitched, whinnying voice (which Aykroyd claimed was based on the voice of Colonel Oliver North).[3]

Arkush also had problems working with Chevy Chase, who was paid a substantial fee for a relatively minimal role. Arkush later recalled, "It was a big paycheck, which Chevy talked about a lot... I went into this thinking that Chevy was committed to this character, but he wasn’t. On his first day, we were working out the blocking for his scene and I said, ‘How do you want to do this, Chevy?’ And he was just pissed at me and said, ‘Why? Don’t you have any ideas?!’”[3] Arkush claimed that two days later, when filming Chase, Arkush offered suggestions to which Chase snapped, “What? Don’t I get any input on this?!” Later, while watching one of his scenes during postproduction, Chase quipped to Arkush, “Call me when you’ve dubbed the laugh track,” before walking off in disgust.[3]

Industrial Light and Magic supplied the visual effects for the scenes involving the animatronic gopher; vocal effects for the creature were provided by veteran voice-over artist Frank Welker.

Music

The music score for Caddyshack II was provided by Ira Newborn. The film's theme song, "Nobody's Fool", was performed by Kenny Loggins, who provided original songs (including the hit song "I'm Alright") for the first Caddyshack. Kenny Loggins had composed and recorded "I'm Alright" for the 1980 Caddyshack film, and was asked by film producer Jon Peters to write a theme song for the sequel.[8] Initially, according to Loggins, "I wasn't so sure when he called about Caddyshack II. I was a little skittish about trusting lightning to strike twice in the same place."[8] Co-written by Loggins and Michael Towers, "Nobody's Fool" was later included as the opening track of Loggins' album Back to Avalon (1988).

Other singles from the Caddyshack II soundtrack include "Power of Persuasion" by The Pointer Sisters; "Go For Yours", an R&B hit for Lisa Lisa and Cult Jam and "Turn On (The Beat Box)" by Earth, Wind & Fire. The soundtrack was released on Columbia Records.

Reception

Caddyshack II was panned by critics and grossed $11,798,302 compared to the original's $39 million gross at the box office.[1] Rotten Tomatoes gives the film a score of 4% based on 24 reviews. The site's consensus reads: "Handicapped by a family friendly PG rating, even the talents of Caddyshack II's all-star comic cast can't save it from its lazy, laughless script and uninspired direction."[9] On Metacritic, the film has a score of 7 out of 100 based on reviews from 7 critics, indicating "overwhelming dislike".[10] Audiences surveyed by CinemaScore gave the film a grade C+ on scale of A to F.[11]

Rita Kempley of The Washington Post wrote: "Caddyshack II, a feeble follow-up to the 1980 laff riot, is lamer than a duck with bunions, and dumber than grubs. It's patronizing and clumsily manipulative, and top banana Jackie Mason is upstaged by the gopher puppet."[12]

Michael Wilmington of the Los Angeles Times said the film was so bad "it makes Caddyshack I look like Godfather II."[13]

Caryn James of The New York Times ended her review of the film with the words, “If [Jackie] Mason hopes to make the kind of segue from stand-up comedy to movies that Mr. Dangerfield did, he and his advisers better think again. Caddyshack II is the kind of film that sends careers spiraling downward.”[14]

Dave Kehr of the Chicago Tribune wrote, "Caddyshack II raises the ghost of summer comedies past. It’s shoddy, lazy and numbingly stupid,” adding, “The comedy is mostly a matter of flatulent animals and falls into swimming pools, and director Allan Arkush (of the engaging Rock 'n' Roll High School) executes it with an uncharacteristic clumsiness... Given the name heavy cast - Randy Quaid, Chevy Chase, and Dan Aykroyd make appearances - it means something that the most fully developed character in the film is a hand puppet gopher.”[15]

The film received four Golden Raspberry Award nominations; it won two. It was nominated for Worst Picture and Worst Actor (Mason) and won for Worst Supporting Actor (Aykroyd) and Worst Original Song ("Jack Fresh").[3] It also won Worst Picture at the 1988 Stinkers Bad Movie Awards.[16]

Harold Ramis recalled, “[PJ] Torokvei and I went to one of the first research screenings in Pasadena, and we literally crawled out of the theater because we didn’t want anyone to see us.”[3]

Mark Canton, Warner Brothers’ head of production at the time Caddyshack II was made, admitted in 2010, “It was troubled from the beginning because Rodney didn’t do it. No offense to Jackie Mason, but it just didn’t work. It was well-intentioned and it was a good business move, but it just wasn’t the same.”[3]

On the subject of Caddyshack II, Bill Murray remarked, "You know, Caddyshack was a great thing. There were some extraordinary people in it, Ted Knight, Rodney Dangerfield, the guy who played the bishop, these are people who have passed away. They were great people, great actors and lots of fun, and it was an unusual thing. Can't you be happy with having seen it and watched it? You want it again?"[17]

In his book My Year of Chevy: One Man's Journey Through the Filmography of Chevy Chase (2013), film critic Mike McGranaghan wrote,

For a few years following its release, I actually kind of liked Caddyshack II. Not in a traditional way, mind you. This is a very bad picture, yet I was fascinated by its utter refusal to deviate from the formula. They theoretically could have gone a hundred different ways or told a brand new story about life at Bushwood, but they didn't. They doggedly held firm to the belief that by simply replicating as many elements from the original as closely as possible, they'd strike comedic gold a second time... My justification for liking Caddyshack II was that it's ultimately a movie about its own failed attempt at a franchise. It is an example of people desperately trying to catch lightning in a bottle twice. For me, that made some of the scenes humorous at the time. I didn't laugh because the comedy was of good quality...I laughed because the intention to duplicate the formula was so blatant that it became sublimely absurd... Any humor [Caddyshack II] contains comes not from the material but from the failed attempt at pulling the material off. I thought that, while it didn't work at the intended level, it did work on a whole other, unintended level. Watching it again 20 years later, I no longer find it to be amusing on any level... Ramis' original [Caddyshack] had, at its core, a number of personal anecdotes about life as a teenage caddy that made it more relatable. The sequel is just forced. It completely loses the anarchic spirit of the first one. It has slobs and snobs but not the underlying heart. The comedy is far too over-the-top, and the message about elitism is so overt that the comedy is suffocated... Ty Webb's famous "be the ball" advice was all about following one's instincts to achieve success. Caddyshack knew how to be the ball, and ended up a comedic hole in one. Caddyshack II sliced into the woods.[18]

Allan Arkush regretted directing Caddyshack II, the experience of which he claimed sent him to therapy.[3] He later said, "You should never make a movie for the wrong reasons. You should only make movies about something where you know no one else can make it better than you... It was my own fault. Everyone who worked on it worked hard and the writers were good. It was great to work with Danny Aykroyd."[7]

References

- ^ a b Klady, Leonard (January 8, 1989). "Box Office Champs, Chumps : The hero of the bottom line was the 46-year-old 'Bambi'". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Caddyshack 2". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 26, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Nashawaty, Chris (July 24, 2020). "The Inside Story of Caddyshack II". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ a b Joshua Klein (March 3, 1999). "Harold Ramis Interview". The A.V. Club. Retrieved December 21, 2010.

- ^ Beck, Marilyn (September 27, 1988). "Dangerfield is picky about scripts for his movies". St. Petersburg Times.

- ^ "Dangerfield Sued". Fort Lauderdale Sun Sentinel. November 4, 1987.

- ^ a b c "Exclusive interview with Allan Arkush". B&S About Movies. December 7, 2021.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=requires|archive-url=(help) - ^ a b Campbell, Mary (August 23, 1988). "Movies Definitely Light Up the Life of Kenny Loggins". Spartanburg Herald-Journal (via the Associated Press). p. C3. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ "Caddyshack II". Rotten Tomatoes.

- ^ "Caddyshack II". Metacritic.

- ^ "Cinemascore". Archived from the original on December 20, 2018. Retrieved August 30, 2019.

- ^ Rita Kempley (July 22, 1988). "'Caddyshack II'". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Movie Review: 'Caddyshack' Sequel Turns Out to Be No Laughing Matter". Los Angeles Times. July 26, 1988.

- ^ James, Caryn (July 23, 1988). "Jackie Mason Re-adjusts His Stand-Up Persona". The New York Times.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=requires|archive-url=(help) - ^ Kehr, Dave (July 25, 1988). "All 'Caddyshack II' offers is stupidity with a message". Chicago Tribune.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=requires|archive-url=(help) - ^ Caddyshack II - Awards - IMDb

- ^ Shackelford, Geoff (February 2, 2006). "Hey Bill, How About A Caddyshack 2?". geoffshackelford.com.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=requires|archive-url=(help) - ^ My Year of Chevy: One Man's Journey Through the Filmography of Chevy Chase by Mike McGranaghan. (2013, Lulu Press), pp.23-24 [ISBN missing]

External links

- 1988 films

- 1980s sports comedy films

- American sequel films

- American sports comedy films

- 1980s English-language films

- Golf films

- Warner Bros. films

- Films with screenplays by Harold Ramis

- Films with screenplays by PJ Torokvei

- Films directed by Allan Arkush

- Films featuring puppetry

- Films scored by Ira Newborn

- Films produced by Jon Peters

- Films produced by Peter Guber

- 1988 comedy films

- Golden Raspberry Award winning films