The Tempest

The Tempest is a play written by William Shakespeare. Although listed as a comedy in the first Folio, modern editors have relabled the play a romance. At the time that it was written it did not attract a significant amount of attention and was to some extent ignored. However, in the twentieth century the play received a sweeping re-appraisal by critics and scholars, to the point that it is now considered one of his greatest works.[1]

Focusing on Prospero's evocative surrender of magic in the play's final scene, traditional critics regularly offered an impressionistic and subjectivist interpretation of the play as Shakespeare's "farewell to the stage" preceding his retirement – though it is certainly not his "final play", as has sometimes carelessly been claimed. The available evidence indicates that Henry VIII and The Two Noble Kinsmen were written later, though both are regarded as collaborations.

One author notes: "Why Shakespeare observed the three unities in The Tempest is not known. In most of his other plays, events occur on several days and characters visit numerous settings. Some scholars have suggested that, because The Tempest contains so much fantasy, Shakespeare may have wanted to observe the unities to help audiences suspend their disbelief. Others have pointed to criticism that Shakespeare received for ignoring the unities; they say he may have wanted to prove once and for all that he could follow rules if he felt like it."[1]

Date and Sources

The Tempest is dated by many conventional scholars circa 1610-11. However, Oxfordian researchers and some modern scholars dispute this dating, arguing for a date closer to 1603-04. (See: Shakespearean authorship and Chronology of Shakespeare's Plays - Oxfordian.) More specific dating is difficult because The Tempest is one of the few of Shakespeare plays for which there is no definitive source for the overall narrative. Conventional scholars see parallel imagery in a report by William Strachey of the real-life shipwreck of the Sea Venture in 1609 on the islands of Bermuda while sailing toward Virginia. Strachey's report was written in 1610; although it was not printed until 1625, it circulated widely in manuscript and many critics believe that Shakespeare may have taken the idea of the shipwreck and some images from it. However, literary scholar Kenneth Muir noted "the extent of verbal echoes of the (Bermuda] pamphlets has, I think, been exaggerated."[2] Muir then cites 13 thematic and verbal parallels between The Tempest and St. Paul's account of his shipwreck at Malta.[3]

Also, some of the words and images in the play seem to derive from Eden's "The Decades of the New Worlde Or West India" (1555) and Erasmus' Naufragium (The Shipwreck) (1523). Both sources are mentioned by previous scholars as influencing the composition of the play[4]. In addition, Oxfordian scholars point to new evidence [2] that seems to confirm Eden and Erasmus as primary sources instead of the "Strachey" report.

The play draws heavily from the tradition of the Romance, which featured a fictitious narrative set far away from ordinary life. Romances were typically based around themes such as the supernatural, wandering, exploration and discovery. Romances were often set in coastal regions, and typically featured exotic, fantastical locations; they featured themes of transgression and redemption, loss and retrieval, exile and reunion. As a result, while The Tempest was originally listed as a comedy in the First Folio of Shakespeare's plays, subsequent editors have chosen to give it the more specific label of Shakespearean romance. Like the other romances, the play was influenced by the then-new genre of tragicomedy, introduced by John Fletcher in the first decade of the seventeenth century and developed in the Beaumont and Fletcher collaborations, as well as by the explosion of development in the courtly masque being conducted by Ben Jonson and Inigo Jones at the same time.

The overall form of the play is modelled heavily on traditional Italian commedia dell'arte performances, which sometimes featured a magus and his daughter, their supernatural attendants, and a number of rustics. The commedia often featured a clown-figure known as "Arlecchino" (or his predecessor, "Zanni") and his partner "Brighella," who bear a striking resemblance to Stephano and Trinculo; a lecherous Napolese hunch-back named "Pulcinella," who corresponds to Caliban; and the clever and beautiful "Isabella," whose wealthy and manipulative father, "Pantalone," constantly seeks a suitor for her, thus mirroring the relationship between Miranda and Prospero.

In addition, one of Gonzalo's speeches is derived from On Cannibals, an essay by Montaigne that praises the society of the Caribbean natives; and much of Prospero's renunciative speech is taken word for word from a speech by Medea in Ovid's Metamorphoses.

Performances and Publication

The earliest recorded performance of The Tempest occurred on November 1, 1611 at Whitehall Palace in London. It was one of the eight Shakespearean plays acted at Court during the winter of 1612-13, as part of the festivities surrounding the marriage of Princess Elizabeth with Frederick V, the Elector of the Palatine in the Rhineland. There is no public performance recorded prior to the Restoration; but in his preface to the 1667 Dryden/Davenant version (see below), Sir William Davenant states that The Tempest had been performed at the Blackfriars Theatre.[5] Such public performances, both there and at the Globe Theatre, would have been highly likely.

The play was not published until its inclusion in the First Folio of 1623, in which it is the first play in the section of Comedies, and therefore the opening play of the collection. The Tempest was frequently acted in adapted forms during the Restoration; see Theatrical Adaptations below. Shakespeare's original text was revived in a 1746 production at Drury Lane.

Plot

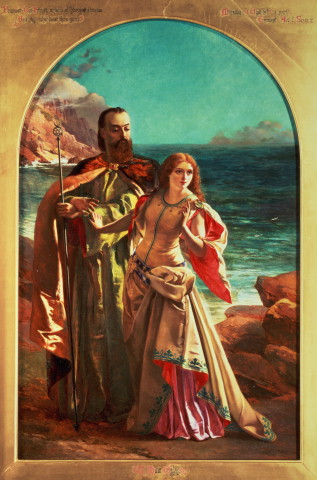

The sorcerer Prospero, rightful Duke of Milan, and his daughter, Miranda, have been stranded for twelve years on an island, after Prospero's jealous brother Antonio—helped by Alonso, the King of Naples—deposed him and set him adrift with the three-year-old Miranda. Prospero secretly sought the help of Gonzalo and their small and shoddy boat had secretly been upgraded to be more than sea worthy, it had been supplied with plenty of food and water, it had an excellent library and contained surviving material in case the boat capsized. Possessed of magic powers due to his great learning and prodigious library, Prospero is reluctantly served by a spirit, Ariel whom he had rescued from imprisonment in a tree. Ariel was trapped therein by the African witch Sycorax, who had been exiled to the island years before and died prior to Prospero's arrival; Prospero maintains Ariel's loyalty by repeatedly promising to release the "airy spirit" from servitude, but continually defers that promise to a future date, namely at the end of the play. The witch's son Caliban, a deformed monster and the only non-spiritual inhabitant before the arrival of Prospero, was initially adopted and raised by the Milanese sorcerer. He taught Prospero how to survive on the island, while Prospero and Miranda taught Caliban religion and their own language. Following Caliban's attempted rape of Miranda, he had been compelled by Prospero to serve as the sorcerer's slave, carrying wood and gathering pig nuts. In slavery Caliban has come to view Prospero as a usurper, and grown to resent both the magus and his daughter for what he believed to be their betrayal of his trust; Prospero and Miranda in turn view Caliban with contempt and disgust.

The play opens as Prospero, having divined that his brother, Antonio, is on a ship passing close by the island (having returned from the nuptials of Alonso's daughter Claribel with the King of Tunis), has raised a storm (the tempest of the title) which causes the ship to run aground. Also on the ship are Antonio's friend and fellow conspirator, King Alonso, Alonso's brother Sebastian, Alonso's royal advisor Gonzalo, and Alonso's son, Ferdinand. Prospero, by his spells, contrives to separate the survivors of the wreck into several groups and Alonso and Ferdinand are separated, and believe one another dead.

Three plots then alternate through the play. In one, Caliban falls in with Stephano and Trinculo, two drunken crew members, whom he believes to have come from the moon, and drunkenly attempts to raise a rebellion against Prospero (which ultimately fails). In another, Prospero works to establish a romantic relationship between Ferdinand and Miranda; the two fall immediately in love, but Prospero worries that "too light winning [may] make the prize light", and so compels Ferdinand to become his servant so that his affection for Miranda will be confirmed. He also decides that after his plan to exact vengeance on his betrayers has come to fruition, he will break and bury his staff, and "drown" his book of magic. In the third subplot, Antonio and Sebastian conspire to kill Alonso and his advisor Gonzalo, so that Sebastian can become King. They are thwarted by Ariel, at Prospero's command. Ariel appears to the three "men of sin" as a harpy, reprimanding them for their betrayal of Prospero. Alonso, Sebastian and Antonio are deeply affected while Gonzalo is unruffled. Prospero manipulates the course of his enemies' path through the island, drawing them closer and closer to him. In the conclusion, all the main characters are brought together before Prospero, who forgives Alonso (as well as his own brother's betrayal, and warns Antonio and Sebastian about further attempts at betrayal) and finally uses his magic to ensure that everyone returns to Italy. Everyone leaves the island apart from Caliban and Ariel who are both left to see who will be Prospero's successor of the island.

Themes / Tropes

This section possibly contains original research. |

Kingships

The concept of usurping a monarch occurs frequently throughout the play: Antonio usurped Prospero; Caliban accuses Prospero of having usurped him upon the latter's arrival on the island; Sebastian plots to kill and overthrow his brother the King of Naples; Stephano has designs to depose Prospero and set himself up as "king o'the isle." As such, the play is simultaneously concerned with what constitutes virtuous kingship, presenting the audience with various possibilities. In the twentieth century, post-colonialism literary critics were extremely interested in this aspect of the play, seeing Caliban as representative of the natives invaded and oppressed by Imperialism. Usurpation in Act 2 The themes of political legitimacy, source of power, and usurpation arise in the second act two. While Prospero firmly believed that the only legitimate power was the power that came from one's knowledge and hard work, Antonio believes that the power he usurped from his brother is legitimate, because he deserved it more and had the skill to wrestle it away. "Look how well my garments sit upon me, much feater than before," Antonio brags to Sebastian; Antonio's lack of remorse over his crime, and his arrogant claim that his power is just because he uses it better, foreshadow a confrontation with his brother Prospero, and an eventual fall from this ill-gained power."

Although Caliban asserted his natural authority over the island in Act 1, Prospero's usurpation of Caliban's power is negated by Caliban's portrayal as a savage seeking a new master. Caliban proves Prospero's view of him, as a natural servant, to be true, when Caliban immediately adopts Stephano as his new master upon Stephano's sudden appearance. Caliban, as a native, is seen as a "monster," not only by Prospero, but by Trinculo and Stephano also; their contempt for dark-skinned Caliban is analogous to Europeans' view of "natives" in the West Indies and other colonies, and Shakespeare's treatment of Caliban provides some interesting social commentary on colonization.

The Theatre

The Tempest is overtly concerned with its own nature as a play, frequently drawing links between Prospero's Art and theatrical illusion. The shipwreck was a "spectacle" "performed" by Ariel; Antonio and Sebastian are "cast" in a "troop" to "act"; Miranda's eyelids are "fringed curtains". Prospero is even made to refer to the Globe Theatre when claiming the whole world is an illusion: "the great globe... shall dissolve... like this insubstantial pageant". Ariel frequently disguises himself/herself as figures from Classical mythology, for example a nymph, a harpie and Ceres, and acts as these in a masque and anti-masque that Prospero creates.

Early critics saw this constant allusion to the theatre as an indication that Prospero was meant to represent Shakespeare; the character's renunciation of magic thus signalling Shakespeare's farewell to the stage. This theory has fallen into disfavour; but certainly The Tempest is interested in the way that, like Prospero's "Art", the theatre can be both an immoral occupation and yet morally transformative for its audience.

Magic

Magic is a pivotal theme in the Tempest, as it is the device that holds the plot together. Prospero commands so much power in the play because of his ability to use magic and to control the spirit Ariel, and with magic, he creates The Tempest itself, as well as controlling all the happenings on the island, eventually bringing all his old enemies to him to be reconciled. Magic is also used to create a lot of the imagery in the play, with scenes such as the masque, the opening scene, and the enchanting music of Ariel.

Colonialism

In Shakespeare's day, most of the world was still being "discovered", and stories were coming back from far off Islands, with myths about the Cannibals of the Caribbean, faraway Edens, and distant Tropical Utopias. With the character Caliban (whose name is roughly anagrammatic to Cannibal), Shakespeare offers an in-depth discussion into the morality of colonialism. Different views are discussed, with examples including Gonzalo's Utopia, Prospero's enslavement of Caliban and Caliban's resentment of this. Caliban is also shown as one of the most natural characters in the play, being very much in touch with the natural world (and far nobler than his two Old World friends Stephano and Trinculo).

- ... the isle is full of noises,

- Sounds and sweet airs, that give delight and hurt not.

- Sometimes a thousand twangling instruments

- will hum about mine ears

Shakespeare drew on Montaigne's essay Of Cannibals, which discusses the values of societies insulated from by European influences.

List of Characters

- Alonso, King of Naples

- Sebastian, his brother

- Prospero, the rightful Duke of Milan and the story's protagonist

Prosperous' means 'good fortune'

- Antonio, his brother, the usurping Duke of Milan

- Ferdinand, son of the King of Naples(Alonso)

- Gonzalo, an honest, optimistic old councilor who gave Prospero food, water, and books

- Adrian and Francisco, lords

- Caliban, deformed slave of Prospero and son of Sycorax

- The name is suggestive of "Carib(be)an," and – given looser, 17th century spelling – an anagram of "cannibal," both of which come from the same word. Both implications suggest he is representative of the natives of the "new world."

- Trinculo, a jester

- The name is linked to the Italian verb "to drink"; appropriate as he is one of the two drunkards of the play.

- Stephano, a drunken butler (sometimes Stefano)

- "Stephan" means "crown" in Greek.

- Miranda, daughter of Prospero, often called "a wonder"

- Her name suggests, literally, a "vision."

- Ariel, a fairy spirit

- The name is certainly suggestive of the "air" element, directly opposing the character to Caliban, who is called "thou earth" by Prospero. In Hebrew the name means "lion of God" - it is therefore interesting that Ariel's voice is once mistaken for the "roar of lions." Ariel's name is indeed not mistaken for the roar of lions, this is merely a quick thinking excuse made by Antonio and Sebastian who are caught standing above Gonzalo and Alonso with their swords drawn about to kill them.

- Sycorax, witch and mother of Caliban (but does not appear in the play)

- the name includes the Latin for "raven", with which she is frequently linked in the play. The stresses individually sound like "sick" and "wracks"; sickness and "wracking" people being two of the more insidious ways Prospero uses his own magic.

- Claribel, daughter of Alonso

- These are the names of Roman Goddesses, apart from Iris who is Greek. Iris was a messenger represented by a rainbow, Ceres was the goddess of growing plants and motherly love and Juno was the Queen of the Heavens.

Adaptations

- See also Shakespeare on screen (The Tempest).

Sir William Davenant and John Dryden adapted a deeply cut version of The Tempest, "corrected" for Restoration audiences and adorned with music set by Matthew Locke, Giovanni Draghi, Pelham Humfrey, Pietro Reggio, James Hart and John Banister. Dryden's remarks, in the Preface to his opera Albion and Albanius give an indication of the struggle later 17th century critics had with the elusive masque-like character of a play that fit no preconceptions. Albion and Albinius was first conceived as a prologue to the adapted Shakespeare (in 1680), then extended into an entertainment on its own. In Dryden's view, The Tempest

"...is a tragedy mixed with opera, or a drama, written in blank verse, adorned with scenes, machines, songs, and dances, so that the fable of it is all spoken and acted by the best of the comedians... It cannot properly be called a play, because the action of it is supposed to be conducted sometimes by supernatural means, or magic; nor an opera, because the story of it is not sung." (Dryden, Preface to Albion and Albinius).

The Tempest has inspired numerous later works, including short poems such as "Caliban Upon Setebos" by Robert Browning, and the long poem The Sea and the Mirror by W. H. Auden. John Dryden and William D'Avenant adapted it for the Restoration stage, adding characters and plotlines and removing much of the play's "mythic resonance". The title of the novel Brave New World, by Aldous Huxley is also taken explicitly from Miranda's dialogue in this play:

- O, wonder!

- How many goodly creatures are there here!

- How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world

- That has such people in't! (V.i.181-4)

Popular Culture Adaptations

- The 1956 science-fiction film Forbidden Planet was inspired by the play, especially with regards to the motives (but not names) of several of the characters, but the story replaces Caliban with a "monster from the id" and Ariel with Robby the Robot.

- The 1968 Star Trek episode entitled "Requiem for Methuselah" also was also inspired by the play.

- A Midsummer Tempest, by Poul Anderson, taking place in a fantasy alternate history recounts a quest to recover Prospero's books for use in the English civil war.

- This Rough Magic by Mary Stewart takes place on a Greek island, where one character hypothesizes the original inspiration for The Tempest came, and the novel is punctuated by many allusions to the play.

- In 1979 British filmmaker Derek Jarman delivered a visually lush screen version of the play which plays upon horror and goth film traditions.

- Paul Mazursky's 1982 film Tempest and was an overt and admitted adaptation of the play with modern setting and characters. The film features John Cassavetes, Gena Rowlands, Raul Julia, Susan Sarandon and Molly Ringwald.

- In 1991, Peter Greenaway directed Prospero's Books, a film adaptation in which Prospero speaks all the lines.

- A cheeky stage musical adaptation, entitled Return to the Forbidden Planet (London, 1990) successfully merged the plot of the film with more Shakespearean characters and dialogue.

- In the early 1980s an Australian surf rock adaptation, "Beach Blanket Tempest", was written by Dennis Watkins and Chris Harriott. It has been produced a number of times, mostly in Australia.

- In the early 1980's, Uncanny X-Men scribe Chris Claremont introduced a character named Caliban, a deformed but kind-hearted mutant who fell hopelessly in love with the character Kitty Pryde, who had been known as Ariel.

- The 1994 Star Trek: The Next Generation episode "Emergence", features Lieutenant Commander Data again working on his acting, portraying Prospero on the holodeck. Ironically Patrick Stewart, who played Captain Jean-Luc Picard in The Next Generation, has performed as Prospero on stage.

- In 1994 Garen Ewing wrote and illustrated a black and white comic strip adaptation.

- Also in 1994, Tad Williams published the novel Caliban's Hour in which Caliban tracks a now-grown Miranda to her home in Italy and insists on recounting his own version of events and exacting revenge. Notable for its sympathetic presentation of Caliban and its representation of Ariel as a fallen angel.

- Neil Gaiman's The Sandman comic book series adapted The Tempest slightly in a 1996 epilogue, closing out the lead character's bargain with Shakespeare.

- In the 1998 version of Fantasy Island, Mr. Roarke (Malcolm McDowell), was assisted by a number of residents of the island, including a shape-shifter named Ariel and another named Cal.

- The television series Lost (2004-) appears to be influenced by Shakespeare's play "The Tempest", which is also about a group of people wrecked on an island in a rather mystic fashion for unknown reasons.

- Joss Whedon's movie Serenity (2005) picked up many of the themes, and some of the names, of both Forbidden Planet and The Tempest, especially the exploration of the appropriate scope of control of other people.

- Dan Simmons wrote a pair of novels, Ilium and Olympos, which, among other works of fiction, are heavily based on The Tempest. Prospero, Ariel, Miranda (Moira in the novels), Caliban, Setebos, and Sycorax all play important roles in the novels.

- The Tempest has also been the frame for multiple social commentary plays including Aime Cesaire's Une Tempete and Philip Osment's This Island's Mine.

- In the Irish music CD " The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem Reunion Concert" Liam Clancy, the youngest of the group, recites a portion of the dialogue from the play prior to the last song of the concert, Will Ye Go, Lassie, Go. The recitation begins with " Boys and girls, our revels now are ended......... and ending with, "And our little life is rounded with a sleep."

Theatrical Adaptations

- The Tempest or, The Enchanted Island. By John Dryden and William Davenant. 1670

- The Mock Tempest or the Enchanted Castle. By Thomase Duffet. 1675

- The Tempest; An Opera. David Garrick. 1756

- The Shipwreck. Anonymous. 1780

- The Virgin Queen. Francis Godolphin Waldron. 1797

- The Enchanted Isle. William and Robert Brough. 1848

- Caliban. Ernest Renan. 1877

- L’Eau de Jouvence. Ernest Renan. 1879

- Une Tempête. Aimé Césaire. 1969

- This Island’s Mine. Philip Osment. 1988

- Return to the Forbidden Planet. Bob Carlton. Mid 1980s. A Rock musical. Originally billed as "Shakespeare's forgotten rock and roll masterpiece".

- The Tempest.Peter Evans. 2006

Musical Adaptations

- In the year he died (1791), Mozart was considering writing an opera based on the play. [6]. This would have been an interesting parallel to his The Magic Flute, also circa 1791.

- According to Anton Schindler, Beethoven's Piano Sonata No. 17 was inspired by the play, though the veracity of this claim is in doubt. Nevertheless, the sonata is commonly referred to as The Tempest. [7]

- In 1821 Frederic Reynolds staged an operatic adaptation of The Tempest at Covent Garden, with music by Sir Henry Bishop.

- Tchaikovsky wrote a fantasy overture inspired by The Tempest.

- "Prospero's Speech", the final soliloquy by Prospero in The Tempest, is sung by Loreena McKennitt in her 1994 album, The Mask and Mirror.

- Arthur Sullivan wrote incidental music for a production of the play in 1861. See The Tempest.

- Jean Sibelius, as one of his last compositions, wrote incidental music for a production of the play. Two suites were published.

- Paul Chihara wrote the ballet "The Tempest", which was premiered by the San Francisco Ballet in 1980. The ballet is notable for being the first full-length American ballet.

- Thomas Adès's opera, The Tempest, was written for the Royal Opera House in London and premiered in 2004. With a libretto by Meredith Oakes, the density of the original text was reduced to paired couplets. The opera was given its American premiere by the Santa Fe Opera in the summer of 2006 and will be revived by the ROH in 2007.

- Ronaldo Miranda's opera "A Tempestade", with a libretto by the composer himself, in Portuguese language, premiered on September 22, 2006 at the Theatro São Pedro in São Paulo.

- Track 2 of The Decemberists' album The Crane Wife "The Island" appears to be a retelling of the story of The Tempest, with references to Sycorax's exile to the island, and the rape of a "Landlord's Daughter." [3]

Notes

- ^ The vast critical and scholarly literature on The Tempest can only be sampled here. See: Gerald Graff and James Phelan, The Tempest: A Case Study in Critical Controversy, London, MacMillan, 2000; Frances A. Yates, Shakespeare's Last Plays: A New Approach, London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1975; Frances A. Yates, The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age, London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1979.

- ^ The Sources of Shakespeaere's Plays (1978)

- ^ Acts 27:1-28:10

- ^ (Eden: Kermode 1958 xxxii-xxxiii; Erasmus: Bullough 1975 VIII: 334-339)

- ^ F. E. Halliday, A Shakespeare Companion 1564-1964, Baltimore, Penguin, 1964; p. 486.

- ^ Eisen, Cliff, New Mozart Documents, Stanford, 1991: 65-67 (document no. 106), quoted in Cairns, Mozart and his Operas

- ^ Barry Cooper, gen. ed., The Beethoven Compendium, Ann Arbor, MI: Borders Press, 1991, ISBN 0-681-07558-9.

See also

- The Magic Flute - As The Tempest (c. 1611) dealt with virtuous kingship, more than a century & a half later Mozart & librettist Schikaneder were dealing with enlightened absolutism in The Magic Flute (1791).

Reference

- McCollum, John I. Jr. The Restoration Stage. Houghton Mifflin Research Series, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Riverside Press, 1961.

External links

- The complete text at Wikisource

- The Tempest - plain vanilla text from Project Gutenberg

- The Tempest - scene indexed, online version of the play.

- The Tempest - HTML version of this title.

- Bermoothes in E. Cobham Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (1898).

- Lesson plans for The Tempest at Web English Teacher

==