History of Winnipeg

The history of Winnipeg comprises its initial population of Aboriginal peoples through its settlement by Europeans to the present day. The first forts were built on the future site of Winnipeg in the 1700s, followed by the Selkirk Settlement in 1812. Winnipeg was incorporated as a city in 1873 and experienced dramatic growth in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Following the end of World War I, the city's importance as a commercial centre in Western Canada began to wane. Winnipeg and its suburbs experienced significant population growth after 1945, and the current City of Winnipeg was created by the unicity amalgamation in 1972.

Pre-European history

Winnipeg lies at the confluence of the Assiniboine River and the Red River, known as The Forks, an historic focal point on canoe river routes travelled by Aboriginal peoples for thousands of years.[1] The general area was populated for thousands of years by First Nations. In prehistory, through oral stories, archaeology, petroglyphs, rock art, and ancient artifacts, it is known that natives would use the area for camps, hunting, fishing, trading, and further north, agriculture. The rivers provided transportation far and wide and linked many peoples-such as the Assiniboine, Ojibway, Anishinaabe, Mandan, Sioux, Cree, Lakota, and others—for trade and knowledge sharing. Ancient mounds were once made near the waterways, similar to that of the mound builders of the south. Lake Winnipeg was considered to be an inland sea, with important river links to the mountains out west, the Great Lakes to the east, and the Arctic Ocean in the north. The Red River linked ancient northern and southern peoples along the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers. The first maps of some areas were made on birch bark by the Ojibway, which helped fur traders find their way along the rivers and lakes.

The name Winnipeg is named after Lake Winnipeg to the north, and the name is related to a native word referring to the cloudy, silt-filled water flowing off the prairies. The first farming in Manitoba appeared to be along the Red River, near Lockport, Manitoba, where maize (corn) and other seed crops were planted before contact with Europeans.

European contact (1700–1869)

Fur trade

The first aboriginal fur traders in the area would have been trading with the Hudson's Bay Company forts to the northeast or with the North West Company forts to the south and east. The Hudson's Bay Company and British colonialists laid claim to the entire area of Rupert's Land in the late 17th century. This entire Hudson Bay drainage basin included the area now known as Winnipeg. Fur traders working with and trading with the Hudson's Bay Company would have travelled and lived along the major rivers, including the Red River.

In 1738, Sieur Louis Damours de Louvières built Fort Rouge on the Assiniboine River for Sieur de La Vérendrye. This early trading post was later abandoned, and its exact location is unknown.[2] The French traded in the area for several decades before Hudson Bay traders arrived. The first English traders visited the area about the year 1767.[3] Fort Gibraltar was built at The Forks by the North West Company in 1809.

Early settlement

In 1811, the Scottish aristocrat and humanitarian Thomas Douglas, 5th Earl of Selkirk, received from the Hudson's Bay Company a grant of 116,000 square miles in the basins of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers, which he named Assiniboia. His goal was to establish the first permanent agricultural settlement along the Red River near the junction of the two rivers, to be inhabited by displaced Scottish Highland families and retired Rupert's Land employees of the Hudson's Bay Company. The Red River Settlement was founded in 1812 and the construction of Fort Douglas was overseen by Miles Macdonell, Lord Selkirk's first Governor of Assiniboia, in 1813–14. This would be the first European agricultural colony on the northern great plains.

The presence of the Selkirk Settlement, which saw much of the open land along the Red and Assiniboine Rivers converted to agricultural uses, added to the growing hostilities between the two main fur trading companies, the Hudson's Bay Company and the North West Company. In the 1810s, the two companies fought fiercely for control of the fur trade in the area, and each destroyed some of the other's forts over the course of several violent skirmishes, like the Battle of Seven Oaks. In 1821, rivalry between the two companies ended with a forced merger, under the Hudson's Bay name.

With a virtual monopoly on the northwestern fur trade, the Hudson's Bay Company relocated their operations at Red River to Fort Gibraltar in 1822, renaming it Fort Garry. This fort, which was demolished in 1852, was located on the present-day site of The Forks National Historic Site in Winnipeg. In 1835, the Hudson's Bay Company began constructing a substantial new Fort Garry, a short distance to the west. This new fort, constructed of stone, would remain the company's leading post until the collapse of the fur trade in the Red River region in the 1870s.[4]

Beginning in the early to mid-19th (the 1820s to 1840s) century the Métis, an ethnic group descended from the mixing of indigenous Canadians and European traders, began settling in the Red River Valley. They were heavily involved in the fur trade as hunters and traders.[5] Important British trading posts included Fort Alexander, operated by the Hudson's Bay Company, and Fort Bas-de-la-Rivière, operated by the North West Company.[6] Additionally as settlers from the U.S. established posts in what is now Minnesota, illegal trade routes known as the Red River Trails developed between the Red River Colony and Saint Paul.[7]

Beginning in 1862, an unincorporated village began to form a short distance north of Fort Garry, near the present-day intersection of Portage Avenue and Main Street. This village became home to a cluster of business enterprises of the longtime landowners of this part of the settlement such as Andrew McDermot and Andrew Bannatyne, as well as a small but growing number of entrepreneurs and small landholders who had recently arrived from the United States and Ontario. Notable among this latter group was the Ontario-born John Christian Schultz.[8] While open commercial trade that was independent of the Hudson's Bay Company had been occurring in the Red River settlement since the Sayer trial of 1849, this concentration of businesses near the intersection of Portage and Main would form the basis of a new urban centre. As the city grew, this area would remain its commercial heart well into the 20th century.[9]

Early post-Confederation Winnipeg (1870–1913)

In 1869, the Hudson's Bay Company formally surrendered its charter rights over Rupert's Land, a territory that includes Winnipeg, back to the Crown. In 1870, the British ceded the territory to the Canadian government, under s. 146 of the Constitution Act, 1867. However, as a result of premature actions by the designated Lieutenant Governor of the area, William McDougall, the people of Red River formed a provisional government and seized Fort Garry in late 1869 until arrangements could be negotiated between its leaders and the Canadian government.

The following dispute resulted in the Red River Rebellion, a conflict between the local provisional government, led by Louis Riel, and the federal Canadian government. The rebellion eventually saw negotiations between the Metis and the government, which led to the passage of the Manitoba Act, and the admittance of Manitoba as a province into Canadian Confederation on 15 July 1870. Shortly before the passage of the Manitoba Act, the Wolseley expedition was dispatched from Toronto to Fort Garry in May 1870. Led by General Garnet Wolseley, and manned by British Army and Canadian militia units, the expedition was sent to quell the rebellion, and counter American settlers encroaching the Canada–United States border. The expedition arrived at Winnipeg on 24 August 1870, capturing the fort that was abandoned by Riel and his supporters. The capture of the fort marked the effective end of the rebellion.

Development and incorporation

This small cluster of houses and commercial buildings near Portage and Main soon began to be referred to as "Winnipeg" by the locals, in order to differentiate themselves from the Hudson's Bay Company operations at Fort Garry.[10] The placename Winnipeg began to appear on the masthead of Red River's weekly newspaper, The Nor'Wester. By the early 1873, this settlement grew to be the main population and commercial centre in the Red River area, with business activity lining Main Street. On November 8, 1873, Winnipeg was incorporated as a city, and elected its first mayor, Francis Evans Cornish, and Council two months later. In 1876, three years after the city's incorporation, the post office officially adopted the name "Winnipeg."[11]

In the vicinity of Fort Garry at The Forks, the Hudson's Bay Company had for decades held a land reserve to be used for company purposes. This reserve measured 465 acres (1.9 square kilometres), which fell within the boundaries of the newly incorporated City of Winnipeg. With the decline of the fur trade at Red River and the growth of its urban centre, the Hudson's Bay Company created a plan of subdivision so it could sell off much of its vast reserve. The Company subdivided the reserve into rectangular blocks on regular grid streets measuring one chain (66' feet), except for Main Street (sometimes called the Garry Road), Portage Avenue and Broadway, which each measured two chains (132 feet) in width. Despite the plan of subdivision, demand for properties remained low in the 1870s, and so building activity in the reserve was limited mainly to along Main Street.

Railways and economic growth

The first locomotive in Winnipeg, the Countess of Dufferin, arrived in Winnipeg via steamboat in 1877, and a railway connection to St. Paul began the following year, via the Pembina Branch. The Pembina Branch ran on the east side of the Red River and terminated in St. Boniface. From there, passengers and goods were transported across the river to Winnipeg by ferry. The Canadian Pacific Railway completed the first direct rail link from eastern Canada in 1881, when the railway crossed the newly constructed bridge across the Red River at Point Douglas, the Louise Bridge. The arrival of the Canadian Pacific Railway opened the door to mass immigration and settlement of Winnipeg and the Canadian Prairies. Today, the history of Winnipeg's rail heritage and the Countess of Dufferin may be seen at the Winnipeg Railway Museum.

With the arrival of the railways, Winnipeg experienced a period of significant population growth, beginning in 1881 and lasting well until the 1910s. The city's population grew from 7,900 in 1881 to more than 179,000 in 1921.[12] The only large city on the Canadian prairies in 1891, and a centre of railway transportation between eastern and western Canada, Winnipeg became the leading commercial centre of the prairie territories and provinces. In succeeding decades as other prairie centres such as Calgary, Edmonton, and Regina become regional centres of trade, Winnipeg's importance as the chief economic centre of Western Canada was reduced, though it retained strong regional importance, particularly as a Western Canadian centre of finance and the grain trade.[13]

Owing to its place as a transportation hub between eastern and western Canada, Winnipeg became a major wholesaling centre in the late 19th century, and many substantial wholesaling warehouses and light manufacturing buildings were constructed on the northern end of the central business district, to the east and west of Main Street.[14] Many of these buildings have remained, and today this warehouse area is known as the Exchange District.

The Manitoba Legislative Building reflects the optimism of the boom years. Built mainly of Tyndall Stone and opened in 1920, its dome supports a bronze statue finished in gold leaf titled, "Eternal Youth and the Spirit of Enterprise" (commonly known as the "Golden Boy"). The Manitoba Legislature was built in the neoclassical style that is common to many other North American state and provincial legislative buildings of the 19th century and early 20th century. The Legislature was built to accommodate representatives for three million people, which was the expected population of Manitoba at the time.

Urban structure

With a rapidly growing population, enlarged urban area, and growing economic importance, a neighbourhood class structure began to form in the 1880s. This structure's most notable character was a general divide based on class and ethnicity between the north and south parts of the city. This began with a real estate boom in 1881 and early 1882, which resulted in the expansion of commercial uses in the centre of the city near Main Street, and significant outward expansion of residential districts.

The North End became home to many of the growing city's working classes and recent immigrants, while many of Winnipeg's wealthy and Canadian-born and British-born citizens settled in the south end of the city. This north-south division would generally continue well into the 20th century, as the working class North End and the wealthier south end expanded further out from Winnipeg's downtown core.[15]

Winnipeg took on its distinctive multicultural character during this period. Many new Canadians that settled in Winnipeg lived in the city's North End. For much of the 20th century, the North End was home to many religious, cultural, and economic institutions of the immigrant communities arriving from Eastern Europe.

In the early 20th century, the residential neighbourhood of Crescentwood was developed and became home to many of Winnipeg's prominent and wealthy citizens.[16]

In 1904, the T. Eaton Company opened a new department store on Portage Avenue, several blocks west of the heart of Winnipeg's central business district. The presence of Eaton's on Portage Avenue led to retail and entertainment operations shifting west from Main Street to Portage Avenue, in order to be near the popular department store. Main Street, however, retained its importance as the city's "Bankers’ Row."[17]

World Wars and the Interwar period (1914–1945)

World War I

With the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914, Winnipeg's central location in Canada's east-west rail system was less important for international trade, and the increase in ship traffic on Canada's west coast helped Vancouver surpass Winnipeg as Canada's third-largest city in the 1960s.[18] Winnipeg's rapid economic growth in the early 20th century was interrupted by the outbreak of World War I in 1914, which sharply curtailed British financial investment and European immigration.

Interwar years

Following World War I, owing to a postwar recession, appalling labour conditions, and the presence of radical union organizers and a large influx of returning soldiers, 35,000 Winnipeggers walked off the job in May 1919 in what came to be known as the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919. After many arrests, deportations, and incidents of violence, the strike ended on June 21, 1919, when the Riot Act was read and a group of Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) officers charged a group of strikers. Two strikers were killed and at least thirty others were injured, resulting in the day's being known as Bloody Saturday; the lasting effect was a polarized population. One of the leaders of the strike, J. S. Woodsworth, went on to found Canada's first major socialist party, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), which would later become the New Democratic Party.

After years of war and recession, Canada's national economy recovered in the early 1920s, and Winnipeg began to see a return to growth and prosperity as a centre for the grain trade, manufacturing, processing, and wholesaling in Western Canada. However, Winnipeg would not see the same level of rapid growth it experienced prior to 1914, and Winnipeg's important economic status among Western Canadian cities would decline as other cities grew.[19]

Winnipeg's population continued to grow in the 1920s, but this was modest compared to the explosive population growth in the early 20th century. While Winnipeg remained the largest of Canada's prairie cities by a wide margin, its population would be surpassed by Vancouver in the 1920s. Much of the population growth 1920s would be in Winnipeg's suburban areas. This growth was owing to the availability of streetcar service from the downtown to suburban areas, and to the rising rates of automobile ownership and improved roads for automobile transportation. Despite population growth in Winnipeg's suburbs, the general urban structure established by 1914 remained largely in place; the downtown was the region's unchallenged centre for trade and finance, shopping, and entertainment.[20]

In the downtown area, Portage Avenue would further establish itself as the primary retail in the street in the 1920s, particularly with the opening of the massive Hudson's Bay Company department store at the corner of Portage Avenue and Memorial Boulevard in 1926.[21]

The stock market crash of 1929 only hastened an already steep decline in Winnipeg; the Great Depression resulted in massive unemployment, which was worsened by drought and depressed agricultural prices.[22]

World War II

The Depression ended when World War II started in 1939. The first Canadian to see the battle was Winnipegger Selby Roger Henderson who enlisted in the RAF just before the start of the war. He participated in the attack on enemy ships at Wilhelmshaven, Germany on September 4, 1939.[23]

The Winnipeg Grenadiers were among the first Canadians to engage in combat against Japan in the Battle of Hong Kong during World War II. Those in the battalion that didn't die in the conflict were captured and brutalized in prisoner-of-war camps.[24]

In Winnipeg, the established armouries of Minto, Tuxedo (Fort Osborne), and McGregor were so crowded that the military had to take over other buildings to increase capacity. In 1942, the Government of Canada's Victory Loan Campaign staged a mock Nazi invasion of Winnipeg to increase awareness of the stakes of the war in Europe.[25] The very realistic invasion included Nazi aircraft and troops overwhelming Canadian forces within the city. Air raid sirens sounded and the city was blacked out. The event was covered by North American media and featured in the film "If Day".

Winnipeg played a large part in the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP). The mandate of the BCATP was to train flight crews away from the battle zones in Europe. Pilots, navigators, bombardiers, wireless operators, air gunners, and flight engineers all passed through Winnipeg on their way to the various air schools across western Canada; Winnipeg served as a headquarters for Command No. 2.[26]

Recent history (1946 to present)

1946–1971

The end of World War II brought a new sense of optimism to Winnipeg. Pent-up demand brought a boom in housing development, but building activity came to a halt due to the 1950 Red River flood, the largest flood to hit Winnipeg since 1861; the flood held waters above the flood stage for 51 days. On May 8, 1950, eight dikes collapsed, four of the city's eleven bridges were destroyed, and nearly 100,000 people had to be evacuated, making it Canada's largest evacuation in history. Premier Douglas Campbell called for federal assistance, and Canadian Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent declared a state of emergency. Soldiers from the Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry regiment staffed the relief effort for the duration of the flood. The federal government estimated damages at over $26 million, although the province insisted it was at least double that.[27]

To protect the city from future flood damage, the Red River Basin Investigation recommended a system of flood control measures, including multiple diking systems and a floodway to divert the Red River around Winnipeg; this prompted the construction of the Red River Floodway under Premier Dufferin Roblin. Construction of the Red River Floodway began in 1962 and was completed in 1968.

In the 1960s, Winnipeg was home to an active rock n' roll scene, which would launch the notable careers of Neil Young and The Guess Who. During this era, few night clubs would book rock groups, so local bands would play at dances held in community halls.[28]

Consolidated Winnipeg

Amalgamation

Despite substantial growth in adjacent suburbs after 1945, the City of Winnipeg was the largest of thirteen cities and towns in the metropolitan area. These municipalities amalgamated under the name Unicity, which was created on July 27, 1971, and legislation took effect on January 1, 1972. Unicity did away with the Metropolitan Corporation of Greater Winnipeg and the 13 municipal governments, creating one city of Winnipeg. The general intentions of Unicity were to streamline urban planning and the provision of municipal services for the metro region and to level major property tax rate inequalities that existed between different municipalities. To address fears that the local interests of various municipalities would not be respected, Unicity created 13 resident advisory groups, which were given some decision-making authority and to inform the new Unicity Council on major decisions.[29]

The City of Winnipeg Act incorporated the current city of Winnipeg; the municipalities of Transcona, St. Boniface, St. Vital, West Kildonan, East Kildonan, Tuxedo, Old Kildonan, North Kildonan, Fort Garry, Charleswood, and the City of St. James, were amalgamated with the Old City of Winnipeg.

Downtown revitalization efforts

In 1979, the Eaton's catalogue building was converted into the first downtown mall in the city. It was called Eaton Place but would change its name to Cityplace following the controversial demolition of the empty Eaton's store in 2002.

Immediately following the 1979 energy crisis, Winnipeg experienced an economic downturn in advance of the early 1980s recession. Throughout the recession, the city incurred closures of prominent businesses such as the Winnipeg Tribune and the Swift's and Canada Packers meat packing plants.[30] In 1981, Winnipeg was one of the first cities in Canada to sign a tripartite agreement to revitalize its downtown area.[31] The three levels of government—federal, provincial and municipal—have contributed over $271-million to the development needs of downtown Winnipeg over the past 20 years. The funding was instrumental in attracting Portage Place mall, which comprises the headquarters of Investors Group, the offices of Air Canada, and several apartment complexes.

In 1989, the reclamation and redevelopment of the CNR rail yards at the junction of the Red and Assiniboine rivers turned The Forks into Winnipeg's most popular tourist attraction.[32]

In 1993, feeling that their community needs were not being fulfilled, the residents of Headingley seceded from Winnipeg and officially became incorporated as a municipality.

In 1996 Winnipeg's National Hockey League team (the Winnipeg Jets) left for Phoenix, Arizona. Fifteen years later, the Atlanta Thrashers of the NHL relocated to Winnipeg for the 2011–12 season.

During the 1997 Red River flood, the floodway was pushed to its limits. The Red River Floodway Expansion is set to be completed in late 2010 at a final cost of more than $665,000,000 CAD.

Political history

The first elections for city government in Winnipeg were held shortly after incorporation in 1873. On January 5, 1874, Francis Evans Cornish, former mayor of London, Ontario, defeated Winnipeg Free Press editor and owner William F. Luxton by a margin of 383 votes to 179. There were only 382 eligible voters in the city at the time, but property owners were allowed to vote in every civic poll in which they owned property. Until 1955, mayors could only serve one term. City government consisted of 13 aldermen and one mayor; this number of elected officials remained constant until 1920.

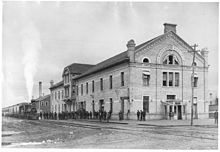

Construction of a new City Hall commenced in 1875. The building proved to be a structural nightmare and eventually had to be held up by props and beams. The building was eventually demolished so that a new City Hall could be built in 1883. A new City Hall building was constructed in 1886. It was a "gingerbread" building, built in Victorian grandeur, and symbolized Winnipeg's coming of age at the end of the 19th century. The building stood for nearly 80 years. There was a plan to replace it around the World War I era (during the construction of the Manitoba Legislative Building), but the war delayed that process. In 1958, falling plaster almost hit visitors to the City Hall building. The tower eventually had to be removed, and in 1962, the whole building was torn down.

The Winnipeg City Council embraced the idea of a "Civic Centre" as a replacement for the old city hall. The concept originally called for an administrative building and a council building, with a courtyard in between. Eventually, a police headquarters and remand centre (the Public Safety Building) and parkade were added to the plans. The four buildings were completed in 1964 in the brutalist style, at a cost of $8.2 million. The Civic Centre and the Manitoba Centennial Centre were connected by tunnels in 1967. The Public Safety Building and parkade were demolished in 2019-2020 for a new mixed use development called The Market Lands.

See also

Notes

- ^ The Forks. "History". Archived from the original on 2008-09-30. Retrieved 2008-11-04.

- ^ The Forks National Historic Site of Canada. "Parks Canada". Retrieved 2007-01-05.

- ^ Narrative of an expedition to the source of St. Peter's River, Lake Winnepeek, Lake of the Woods, &c., &c. performed in the year 1823, by order of the Hon. J.C. Calhoun, secretary of war, under the command of Stephan H. Long, major U.S.T.E. / Author: Colhoun, James Edward.

- ^ Manitoba Historical Society. "The Old Forts of Winnipeg, 1738-1927". Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ Risjord (2005), p. 41.

- ^ Wilson (2009), p. lx.

- ^ Gilman (1979), pp. 8, 14.

- ^ Manitoba Historical Society. "The Man Who Created the Corner of Portage and Main". Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ Artibise, Allan. Winnipeg: An Illustrated History. Toronto: James Lorimer & Company. 1977.

- ^ Korneski, Kurt. Race, Nation, and Reform Ideology in Winnipeg, 1880s-1920s. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. 2015

- ^ Artibise, Winnipeg: An Illustrated History.

- ^ U Guelph. "U Guelph". Archived from the original on 2007-06-29. Retrieved 2007-10-03.

- ^ Gerald, Friesan (1987). The Canadian Prairies: A History (Student ed.). Toronto and London: University of Toronto Press. pp. 274–280, 534. ISBN 0-8020-6648-8.

One by one, the city's prairie-wide functions were whittled away; by 1940, though still the first city of the prairies... It had become merely the capital of a province, the economic and transportation centre of a limited trading area, rather than the metropolis of the entire Western interior.

- ^ Artibise. Winnipeg: An Illustrated History.

- ^ Hiebert, Daniel. "Class, ethnicity and residential structure: the social geography of Winnipeg, 1901-1921." Journal of Historical Geography, 17 (1991), 56-86.

- ^ Manitoba Historical Society. "A Walking Tour of Crescentwood". Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ Artibise. Winnipeg: An Illustrated History.

- ^ Planetware. "Winnipeg, Manitoba". Retrieved 2007-10-03.

- ^ Artibise. Winnipeg: An Illustrated History.

- ^ Artibise. Winnipeg: An Illustrated History.

- ^ Hudson's Bay Company Heritage. "Winnipeg". Retrieved 2018-04-02.

- ^ The Dirty Thirties in Prairie Canada: 11th Western Canada Studies. Western Canadian Studies Conference (11th: 1979: University of Calgary). Edited by R. D. Francis and H. Ganzevoort. Vancouver: Tantalus Research, 1980. ISBN 0-919478-46-8.

- ^ Manitoba 125 - A History v. 3. Edited by Greg Shilliday. Winnipeg: Great Plains Publications. 1995. ISBN 0-9697804-1-9

- ^ "Canadians in Hong Kong". Veteran Affairs Canada. Archived from the original on 2012-12-17. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ^ "February 19, 1942: If Day". Manitoba Historical Society. Retrieved 2009-06-07.

- ^ "World War II". Canadawiki. Archived from the original on 2007-05-22. Retrieved 2007-05-16.

- ^ "Manitoba Royal Commission". American Review of Canadian Studies. Retrieved 2007-07-04.

- ^ Einarson, John. "When Winnipeg Rocked". Winnipeg Free Press. 9 November 2014.

- ^ Dudley, Michael. "Forty years after its inception, Unicity is generally considered a noble failure". The Uniter. Retrieved 2018-04-03.

- ^ "Hansard". Manitoba Legislature. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2007-08-08.

- ^ "Urban Development Agreements". Western Economic Diversification Canada. Archived from the original on 2008-04-17. Retrieved 2008-04-29.

- ^ "History". The Forks. Archived from the original on 2009-02-09. Retrieved 2009-05-03.

References

- Gilman, Rhoda R.; Gilman, Carolyn; Miller, Deborah L. (1979). Red River Trails : Oxcart Routes Between St Paul and the Selkirk Settlement 1820-1870. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-87351-133-9.

- Risjord, Norman K. (2005). A Popular History of Minnesota. Saint Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 0-87351-532-3.

A Popular History of Minnesota.

- Wilson, Maggie (2009). Rainy River Lives. Omaha: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-2062-1.

Further reading

- Artibise, Alan FJ. Winnipeg: a social history of urban growth, 1874-1914 (McGill-Queen's Press-MQUP, 1975)

- Bellan, Ruben C. Winnipeg, first century: An economic history (Queenston House Publishing Company, 1978)

- Cavett, Mary Ellen, H. John Selwood, and John C. Lehr. "Social Philosophy and the Early Development of Winnipeg's Public Parks." Urban History Review/Revue d'histoire urbaine (1982) 11#1 pp: 27–39.

- Dafoe, John W. "Early Winnipeg Newspapers: The Last 70 Years of Journalism at Fort Garry and Winnipeg," Manitoba Historical Society Transactions, Series 3, 1946-47 online

- Hiebert, Daniel. "Class, ethnicity and residential structure: the social geography of Winnipeg, 1901–1921." Journal of Historical Geography (1991) 17#1 pp: 56–86.

- Jones, Esyllt Wynne. Influenza 1918: Disease, Death, and Struggle in Winnipeg (University of Toronto Press, 2007)

- Keshavjee, Serena, and Herbert Enns. Winnipeg modern: architecture, 1945-1975 (Univ of Manitoba Press, 2006)

- Korneski, Kurt. "Britishness, Canadianness, class, and race: Winnipeg and the British world, 1880s–1910s." Journal of Canadian Studies/Revue d'études canadiennes (2007) 41#2 pp: 161–184.

- Lightbody, James. "Electoral Reform in Local Government: The Case of Winnipeg." Canadian Journal of Political Science (1978) 11#2 pp: 307–332.

- Matwijiw, Peter. "Ethnicity and urban residence: Winnipeg, 1941-1971." Canadian Geographer 23 (1979): 45–61.

- Nursey, Walter R; Begg, Alexander (2008). History of the City of Winnipeg. BiblioLife. ISBN 978-0-554-45209-8.

- Perrun, Jody. The Patriotic Consensus: Unity, Morale, and the Second World War in Winnipeg (2014)