Indigenous Voice to Parliament

The Indigenous Voice to Parliament (the Voice) is the proposed new advisory group containing separately elected Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, enshrined in the Constitution of Australia, which would "have a responsibility and right to advise the Australian Parliament and Government on national matters of significance to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples".

The request for creating the Indigenous Voice to Parliament was a result of the May 2017 Uluru Statement from the Heart, delivered by the First Nations National Constitutional Convention which met at Uluru. This request was refused by the Turnbull government, on the grounds that it "would be seen as third chamber of parliament".[1] After Scott Morrison became prime minister of Australia in August 2018, his government proposed the Indigenous voice to government in October 2019, which would introduce a body via legislation, without changing the Constitution. The process by which the channel would be established was known as the Indigenous voice co-design process. The Senior Advisory Group was set up under Minister for Indigenous Australians, Ken Wyatt.

With a change of government on 23 May 2022, new prime minister Anthony Albanese promised in his victory speech that a referendum to decide the Indigenous Voice to Parliament enshrined in the Constitution would be held within his term of office. In July 2022 he outlined further plans regarding the referendum, and proposed that the advisory group be named the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice. As of February 2023[update], the details of what the Indigenous Voice to Parliament will involve have not been confirmed. The new process is being overseen by Labor's Minister for Indigenous Australians Linda Burney. Whilst the Peter Dutton-led Opposition Liberal Party has thus far reserved its position on the referendum pending further details from the Labor Government on the nature of the proposed Voice, their junior Coalition partner Nationals have declared themselves against the proposal, with their Aboriginal Senator for the Northern Territory Jacinta Price arguing that it will enshrine a racially divisive bureaucracy into the Constitution, that cannot be dismantled.

Background

The ancestors of today's Aboriginal Australians are believed to have commenced arriving on the Australian continent around 60,000 years ago. Gradually they settled the whole continent of Sahul (which incorporated modern Australia, Tasmania and New Guinea), forming hundreds of language groups, and living millennia in relative isolation.[2] There is contested genetic evidence of an additional wave of migration from the Indian subcontinent to northwestern Australia around 4,000 years ago.[3] Around 10,000 years ago global sea level rose, separating mainland Aboriginal peoples, Aboriginal Tasmanians, Torres Strait Islanders and Papuan peoples (in New Guinea) from each other.[4] There was significant contact between northern Aboriginal people and Makassar people from the 1600s until 1907.[5]

The First Fleet of British settlers arrived in 1788, and the British gradually settled the entire continent as well as Tasmania. There were no treaties between the British and Indigenous Australian peoples, the British established control after a series of violent conflicts known as Frontier Wars. Along with various epidemics (eg: flu, smallpox) and starvation, this led to drastic population decline among Indigenous peoples during the 19th century.

The geographical description of "Australia" was invented in the early 19th century, and the Commonwealth of Australia with its Australian Constitution was founded on 1 January 1901, gathering together the six former British colonies following a series of referenda in which Indigenous people could not take part. Indigenous Australians became Australian citizens in 1948, at the same time as all other Australians. Prior to this, Australians were "British Subjects". Indigenous Australians had uneven rights to vote and stand for Australian Parliaments up until the 1960s. Since 1973, there have been four elected national, representative indigenous bodies advising Australian governments. The bodies generally struggled with maladministration, and lack of engagement from indigenous Australians and were consequently disbanded by successive governments.[6][unreliable source?]

Indigenous Australians in Parliament

The rights of indigenous Australians to vote and stand for Parliament faced uneven restrictions across state and federal jurisdictions up until the 1960s. By the election of the second Menzies Government in 1949, indigenous people were still excluded from voting in Federal Elections in Queensland and Western Australia because of state legislation. Between 1949 and 1962, Menzies dismantled remaining restrictions on Federal voting rights, commencing with Aboriginal ex-servicemen in 1949, and concluding with the 1962 Commonwealth Electoral Act, which granted all indigenous people the option to enrol and vote in federal elections. Queensland became the last state to remove restrictions on state voting in 1965.[7][8][9]

The first Aboriginal parliamentarians began to emerge at a state level from 1969 and, in 1971, Liberal Neville Bonner entered the Senate, as representative for Queensland. He was the first Aboriginal Federal Parliamentarian.[10] Indigenous representation in Australian State and Federal Parliaments has grown markedly in the 21st century. In 2010, Liberal Ken Wyatt became the first Aboriginal member of the House of Representatives. In 2019, he became the first Aboriginal Cabinet Minister. In 2013, Northern Territory Chief Minister Adam Giles of the Country Liberal Party became the first Aboriginal to lead an Australian State or Territory. The 2022 Australian federal election resulted in a record 11 Aboriginal parliamentarians, representing 4.8% of all parliamentarians, which is higher than the Indigenous Australian population of 3.3%.[11]

Elected voices to Parliament

The National Aboriginal Consultative Committee was created in 1973 by the Whitlam government with a principal function to advise the Department of Aboriginal Affairs and the Minister on issues of concern to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Its members were elected by Indigenous people.[12] The Fraser Government commissioned the Hiatt Committee review of the body in 1976, which concluded that it had not functioned as a consultative committee or been effective in providing advice to government or in making its activities known to most Aboriginal people.[6][unreliable source?] To address these failing, the body was reconstituted in 1977 as the National Aboriginal Congress (NAC), which was also an elected body.[13]

The Hawke Government commissioned the Coombs Review into the NAC in 1983, and found that the body was not held in high regard by the Aboriginal community and was failing to influence government. In 1985, a Commonwealth Auditor-General audit, found financial mismanagement and irregularities and breaches of its charter and rules.[6][unreliable source?] The body was abolished by the Hawke government in 1985.[14]

ATSIC was the next elected body that provided an Indigenous voice to government, and also had responsibility for administering Aboriginal programs and service delivery. It was established by the Hawke government on 5 March 1990 through the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission Act 1989. Voter turnout for ATSIC was persistently below 25% and its leadership became embroiled in criminal convictions and misappropriation of funds.[6][unreliable source?]

ATSIC was abolished by the Howard government with the support of the Beazley Labor opposition on 24 March 2005. Prime Minister Howard and Indigenous Affairs Minister Amanda Vanstone announced in 2004: "We believe very strongly that the experiment in separate representation, elected representation, for indigenous people has been a failure," and proposed to establish a consultation model based on appointment of "distinguished indigenous people to advise the Government on a purely advisory basis".[15] This body was established as the National Indigenous Council (NIC) in November that year.

A government inquiry into the demise of ATSIC recommended in March 2005 that the government appointed NIC "be a temporary body, to exist only until a proper national, elected representative body is in place".[16] The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner specifically called for a more representative voice in the Australian Human Rights Commission's Social Justice Reports of 2006 and 2008.[17]

In early 2008, the NIC was disbanded, and in December that year, the Rudd government asked the Human Rights Commission to develop a new elected Indigenous representative body.[18] This was announced as the National Congress of Australia's First Peoples in November 2009.[19] The Congress was established as a body independent of government, aiming to avoid the problems ATSIC had.[20] According to Warren Mundine, "where its predecessors were marred by conflict and controversy, Congress struggled with relevance. Fewer than 10,000 Indigenous people signed up as members to elect Congress delegates."[6] The Abbott government cut off the main funding stream for the Congress in 2013. It went into voluntary administration in June 2019,[21] before ceasing completely in October 2019.[22]

Calls for a new voice came from the Cape York Institute in 2012 and 2015.[17] The institute's Noel Pearson formulated the need and rationale for constitutional recognition in his 2014 contribution "A Rightful Place: Race, Recognition and a More Complete Commonwealth" for Quarterly Essay.[23]

Indigenous Australians in the Constitution

Since 1967, the Australian Constitution grants the Federal Government powers to make laws for indigenous Australians. The Liberal Holt Government called a referendum in 1967 referendum to "omit certain words relating to the people of the Aboriginal race in any State and so that Aboriginals are to be counted in reckoning the Population". Over 90% of Australians voted 'yes' in the referendum, and from that time forward, indigenous people were automatically counted in the census.[24][25]

Following the 1998 Australian Constitutional Convention, the Howard Government sought to have reference to Indigenous Australians included in a new Preamble to the Constitution. The proposed preamble included the words: "We the Australian people commit ourselves to [...] honouring Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders, the nation's first people, for their deep kinship with their lands and for their ancient and continuing cultures which enrich the life of our country", however the preamble was rejected in a 1999 referendum.

On 16 October 2007, Prime Minister John Howard promised to hold a referendum on constitutional recognition, and then Labor leader Kevin Rudd gave bipartisan support.

On 8 November 2010 Prime Minister Julia Gillard announced plans for a referendum on the issue.[26] At this time, the Expert Panel on Constitutional Recognition of Indigenous Australians was formed to determine how best to do this. In January 2012, the panel released their final report, which did not recommend the establishment of a new representative body.[27]

The Abbott Government committed itself to pursuing recognition of Indigenous people in the Constitution.[28] In November 2012, the all-party Joint Select Committee on Constitutional Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples was announced, and first met in 2014. It was chaired by Liberal MP Ken Wyatt. It's "Final Report" of June 2015 noted Noel Person's and others' requests for stronger forms of Indigenous representation, however did not recommend that a new body for this purpose be created.[29][30]

Abbott said he hoped the wording for a referendum could be concluded in 2016, for a referendum vote in 2017.[31] The referendum was not implemented by the successor Turnbull Government, and debate shifted towards formation of a constitutionally recognised advisory body.

A constitutional voice to Parliament

An Indigenous Voice

On 7 December 2015 a 16-member Referendum Council was appointed by Liberal prime minister Malcolm Turnbull and the ALP's Bill Shorten.[32] In October 2016, the Council released the "Discussion Paper on Constitutional Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples" which included a call for "An Indigenous voice".[33] The Council then met with over 1,200 people. This led to the First Nations National Constitutional Convention on 26 May 2017, whose delegates collectively composed the Uluru Statement from the Heart. This statement included the request, "We call for the establishment of a First Nations Voice enshrined in the Constitution."[34]

On 13 June 2017, the Referendum Council released their "Final Report". This included the recommendation "That a referendum be held to provide in the Australian Constitution for a representative body that gives Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander First Nations a Voice to the Commonwealth Parliament. One of the specific functions of such a body, to be set out in legislation outside the Constitution, should include the function of monitoring the use of the heads of power in section 51(xxvi) and section 122. The body will recognise the status of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the first peoples of Australia."[35]

In response to this, the federal government established the Joint Select Committee on Constitutional Recognition relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples in March 2018.[36] It was tasked with reviewing the findings of the Uluru Statement delegates, Referendum Council and the two earlier constitutional recommendation bodies. The committee published it's "Final Report" in November 2018, including four recommendations. The first of which was: "In order to achieve a design for The Voice that best suits the needs and aspirations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, the Committee recommends that the Australian government initiate a process of co-design with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples".[37]

The Select Committee stated in the report that the delegates at the 2017 Convention "understood that the primary purpose of The Voice was to ensure that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voices were heard whenever the Commonwealth Parliament exercised its powers to make laws under section 51(xxvi) and section 122 of the Constitution."[38] That is, laws made specifically regarding Australian Indigenous people; or for the Northern Territory, which has a high proportion of Indigenous people.

Co-design of the Voice

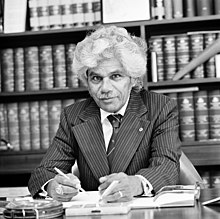

Ken Wyatt

On 30 October 2019, Ken Wyatt AM, Minister for Indigenous Australians in the Morrison government, announced the commencement of a "co-design process" aimed at providing an Indigenous voice to government. The Senior Advisory Group (SAG) was co-chaired by Professor Tom Calma AO, chancellor of the University of Canberra, and Professor Dr Marcia Langton, associate provost at the University of Melbourne, and was to comprise a total of 20 leaders and experts from across the country.[39] There was some scepticism about the process from the beginning, with the criticism that it did not honour the Uluru Statement from the Heart's plea to "walk with us in a movement of the Australian people for a better future".[40] According to Michelle Grattan, "...it is notable that it is calling it a 'voice to government' rather than a 'voice to parliament' ". Prime Minister Scott Morrison rejected the proposal in the Uluru Statement for a voice to parliament to be put into the Australian Constitution; instead, the voice will be enshrined in legislation. The government also said it would run a referendum during its present term about recognising Indigenous people in the Constitution "should a consensus be reached and should it be likely to succeed".[41]

The models for the voice were planned to be developed in two stages:[41]

- First, two groups, one local and regional and the other a national group, will create models aimed at improving local and regional decision-making, and identifying how best federal government can record Indigenous peoples' views and ideas. The groups consist mainly of Indigenous members.

- Consultations will be held with Indigenous leaders, communities and stakeholders to refine the models developed in the first stage.

Wyatt said that he doesn't mind what models are used, and they may vary across the country. His prime targets are suicide prevention and Closing the Gap. A meeting with Prime Minister Scott Morrison, senior ministers and peak Aboriginal community representatives had agreed on "priority reforms", which included greater Aboriginal involvement in decision-making and service delivery at all levels, and a commitment to ensuring that "all mainstream government agencies and institutions undertake systemic and structural transformation to contribute to closing the gap". Wyatt said that he would need to manage expectations on all sides as he seeks to build a consensus on the matter.[42]

Three groups

The original other members of the Senior Advisory Group (SAG) (besides Langton and Calma) included, among others, Frank Brennan, Josephine Cashman, Mick Gooda, Chris Kenny, Vonda Malone, June Oscar, Noel Pearson, Pat Turner, and Galarrwuy Yunupingu.[43][44] The first meeting of the group was held in Canberra on 13 November 2019.[45] It was planned that the SAG would propose models for the voice by June 2020.[42] Cashman was dismissed from the SAG on 28 January 2020 after her involvement with commentator Andrew Bolt in denouncing the Aboriginal identity of author Bruce Pascoe.[46][47][48]

The National Co-design Group was announced on 15 January 2020, to be co-chaired by Donna Odegaard AM and Ray Griggs AO, CSC. The other 15 members include Fred Chaney AO, Joseph Elu AO, Jeff Kennett AC, Fiona McLeod AO, SC, and Gracelyn Smallwood AM.[49]

On 4 March 2020 the third tier, the Local and Regional Co-Design Group, was announced, to be co-chaired by Peter Buckskin and National Indigenous Australians Agency senior official Letitia Hope. Members included Dr Getano Lui (Jnr), Albert McNamara, Aden Ridgeway and Marion Scrymgour.[50][51] The group met for the first time in Sydney on 19 March 2020.[52]

2021 SAG reports

An interim report by the Senior Advisory Group led by Langton and Calma was delivered to the government in November 2020,[53] and officially published on 9 January 2021. It included proposals that the government would be obliged to consult the Voice whenever it was going to create new legislation relating to race, native title or racial discrimination, where it would affect Indigenous Australians. However, the Voice would not be able to veto the enactment of such laws, or change government policies. The Voice would comprise either 16 or 18 members, who would either be elected either directly or come from the regional and local voice bodies.[54] On the same day, Wyatt announced a second stage of co-design meetings lasting four months, involving more consultation with Indigenous people.[55]

Calma reported in March 2021 that about 25 to 35 regional groups would be created, with a mechanism for individuals to pass ideas up the chain from local to regional.[56]

In July 2021 the Indigenous Voice Co-design Process panel released its final report.[57][58] It proposed that the Voice would "have a responsibility and right to advise the Australian Parliament and Government on national matters of significance to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples".[59] It provided detailed proposals on how both a "National Voice" and "Local & Regional Voices" would operate. The report did not cover changing the Constitution (and therefore requiring a referendum), as this was outside its terms of reference.[60] In November it was announced that the report would be considered in parliament as soon as possible; however, sitting time was very limited before the summer break.[61]

Anthony Albanese

In the 2022 Australian federal election in May, a Labor government was elected, with Anthony Albanese to serve as prime minister of Australia. In his victory speech, Albanese said that a referendum to decide the Indigenous Voice to Parliament would be held within his term of office. Incoming Minister for Indigenous Australians Linda Burney would be overseeing the process, and she has said that there would need to be a far-reaching public education campaign to explain the voice to the Australian public before a referendum could be held. At that time (May 2022), it was still not clear exactly what a voice to parliament would look like; there were still differing views within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities about the proposal; and questions about whether an advisory body without the power of veto over parliament was ambitious enough.[62]

At the Garma Festival of Traditional Cultures in July, Albanese spoke in more detail of the government's plans for a voice to parliament. He proposed to add the following three lines to the Constitution:

- There shall be a body, to be called the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice.

- The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice may make representations to Parliament and the Executive Government on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples.

- The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws with respect to the composition, functions, powers and procedures of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice.[63][64][65]

The wording of the second line contrasts with the wider advice function scope in Langton's and Calma's report.[66]

He also proposed that the actioning referendum ask the following question:

Do you support an alteration to the Constitution that establishes an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice?[63]

It has been pointed out that the relevant Referendum (Machinery Provision) Act[67] requires a more detailed ballot wording and does not allow Albanese's simple phrasing.[68]

Referendum preparation

The first meetings of the Referendum Working Group (RWG) and the Referendum Engagement Group (REG) were held in Canberra on 29 September 2022. The RWG, co-chaired by minister Linda Burney and special envoy Patrick Dodson, includes a broad cross-section of representatives from First Nations communities across Australia. They will provide advice to the Government on how best to ensure a successful Referendum and focus on the key questions that need to be considered in the coming months, including:[69]

- The timing to conduct a successful referendum

- Refining the proposed constitutional amendment and question

- The information on the Voice necessary for a successful referendum

The RWG includes Ken Wyatt, Tom Calma, Marcia Langton, Megan Davis, Jackie Huggins, Noel Pearson, Pat Turner, Galarrwuy Yunupingu, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner June Oscar, and a number of other respected leaders and community members. The REG includes those on the RWG as well as other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representatives from across the country, including land councils, local governments and community-controlled organisations. Mick Gooda, Kado Muir, and Hannah McGlade are included in this larger group. They will provide advice about building community understanding, awareness and support for the referendum.[69]

On 28 December 2022 at the Woodford Folk Festival, Prime Minister Albanese announced that the referendum would be held within a year.[70][71]

From the Heart campaign

"From the Heart" is a campaign of the Cape York Institute designed to increase awareness and understanding of the Uluru Statement from the Heart and a constitutionally-enshrined voice to parliament, and to show that it is a fair and practical reform.[72] Torres Strait Islander man Thomas Mayor, advocate for the Uluru Statement and the Voice, delivered the 2022 Vincent Lingiari Memorial Lecture on the topic. He drew parallels between Vincent Lingiari's struggle to be heard by governments back then, leading to the Wave Hill walk-off (Gurdindji strike), to what Indigenous peoples of Australia are experiencing today.[73]

In April 2022, From the Heart suggested two dates for a referendum to decide whether to enshrine a voice to parliament in the Constitution: 27 May 2023 or 27 January 2024.[74]

A new education campaign led by Roy Ah-See, called "History is Calling", was launched in early May 2022, to encourage Australians to answer the Uluru Dialogue's 2017 invitation, and to support the constitutionally-enshrined voice.[74] In September 2022, From the Heart released a video ad to promote a yes vote for the Voice in a referendum, as part of the "History is Calling" campaign.[75]

Opposition to the Voice proposal

Opposition to the proposal has been voiced from within both non-indigenous and indigenous communities, and from within both conservative and progressivist circles.

Voice No Case Committee

The Voice No Case Committee’s “Recognise a Better Way” campaign was launched in January 2023, and argues that the Voice is “the wrong way to recognise Aboriginal people or help Aboriginal Australians in need”. The committee includes four Indigenous members and two former ministers, including former Howard Government Deputy Prime Minister John Anderson and former Keating Government minister turned hard-right activist Gary Johns. The Indigenous members of the committee are Northern Territory Country Liberal party senator Jacinta Price; former president of the ALP-turned Liberal candidate Warren Mundine, founder of the Northern Territory Kings Cross Station Ian Conway, and Bob Liddle, owner of Kemara enterprises. The committee views the idea of the Voice being added to the Constitution as "racially discriminatory" and instead proposes a three-point plan to recognise Aboriginal prior occupation in a preamble to the constitution, establish a parliamentary committee for native title holders, and support Aboriginal community-controlled organisations.[76][77]

Juridicial concerns

Former High Court judge Ian Callinan has written that the Voice will operate "in substance a kind of a separate parliament" and "will give rise to many arguments and division, legal and otherwise", and has criticised the Albanese Government's "Orwellian" intent not to fund both sides of the public debate ahead of the referendum, but instead to fund a "public education program" to support its proposal. Callinan has called for clarification of the intended franchise and financial and judicial oversight methods. He predicts that the body will become party political, and that he foresees "a decade or more of constitutional and administrative law litigation arising out of a voice whether constitutionally entrenched or not [...] I can imagine any number of people and legal personalities in addition to the states who might plausibly argue that they have standing. Standing is a highly contestable matter. "[78]

The Coalition

While the Opposition Leader Peter Dutton's Liberal Party is yet to declare a position (pending further detail from the Albanese Government on the nature of the proposal) their junior Coalition partner the Nationals have declared themselves against the proposal. Nationals leader David Littleproud announced on 28 November 2022 that "as the men and women who represent regional, rural and Indigenous and remote Australians ... we don't believe this will genuinely close the gap...", saying the party instead believed in "empowering local Indigenous communities... to give those communities the opportunities that those in metropolitan Australia enjoy every day". In supporting her leader's announcement, Aboriginal Senator for the Northern Territory Jacinta Price said that "What we need now is practical measures and we have to stop dividing our nation along the lines of race."[79] Dutton's queries on the nature of the voice have been characterised as both ensuring Australians have enough information on the proposal, but also trying to split the Yes vote along the lines of different models for a voice, as John Howard did with the 1999 Australian republic referendum.[80]

Senator Price, along with former Liberal Senate candidate Warren Mundine have been among the leading Aboriginal voices against the Uluru Statement and Albanese Government Voice proposal, arguing that it does not represent indigenous consensus, and that it will only create a new layer of bureaucratic management and interference by elites over the lives of indigenous people and communities, while overturning the principle of equal rights for all races under Australian law. In a 2022 book entitled Beyond Belief… Rethinking the Voice to Parliament, Senator Price wrote: "The globally unprecedented Voice proposal will divide Australia along racial lines... It will constitutionally enshrine the idea that Aboriginal people are perpetual victims - forever in need of special measures." Mundine wrote for the same publication: "The Voice sounds to me like more bureaucracy controlling Indigenous lives and bossing us around."[81]

Former National Party leader Barnaby Joyce told Sky News Australia that the Voice to Parliament would do "real harm by dividing" the Australian population by race; that it would give unequal representation for "one group of people" due only to race, thus creating a divide in the population.[82]

Whilst the constitutionally conservative John Howard and Tony Abbott Liberal-National Governments actively supported inserting recognition of indigenous Australians into the Constitution, both leaders have rejected the idea of creating a Constitutionally enshrined "Voice" to Parliament. Whilst in office, their successor Turnbull and Morrison Coalition governments also rejected the Voice proposal. In 2017, Turnbull declared in a joint statement with Attorney General George Brandis and Indigenous Affairs Minister Nigel Scullion that it "would inevitably become seen as a third chamber of parliament" and that "the Referendum Council provided no guidance as to how this new representative assembly would be elected or how the diversity of Indigenous circumstance and experience could be fairly or democratically represented,” the statement said. Moreover, the government does not believe such a radical change to our constitution's representative institutions has any realistic prospect of being supported by a majority of Australians in a majority of states.[1] (Turnbull reversed his opposition to the proposal following the election of the Albanese Government).

In November 2022, John Howard told The Australian newspaper that "people saw the 1967 referendum as a demonstration of our good faith. But people see the voice as creating potential divisions."[83] Tony Abbott wrote for the same publication that he objected to the Voice proposal because it was "race based", would "vastly complicate" the difficulties of getting legislation passed and anything done; was a "vague-yet-portentous concept" that would invite High Court review and delay; and that ultimately, the cause of Reconciliation would be set back if the referendum fails, and that this was likely given the lack of bipartisan support as indicated by "new Coalition senator for the Northern Territory, the proud “Celtic-Warlpiri Australian” woman Jacinta Price, [expressing] deep scepticism about a proposal with so much of the detail thus far omitted, with so much potential for ineffective posturing, and that defines people by racial heritage."[84]

The National Party of Australia opposes the Voice as party policy.[85] The decision led to Andrew Gee leaving the party to sit as an independent.[86]

Minor Parties and other opponents

Independent Senator Lidia Thorpe, formerly representing the Australian Greens party, has described the Voice to Parliament referendum as a "waste of money", and said that it would be better to divert the funds into Indigenous communities, but Greens Leader Adam Bandt has dismissed her concerns and supports the Voice.[87] Thorpe has also said that a "treaty" with indigenous Australians should come first – not the Voice,[88] and in January 2023 left the Greens party over differences with the rest of the party. [89] She has also expressed concerns that the Voice model will impact on Indigenous sovereignty.[90] The conveners of the Greens’ First Nations advisory group ‘First Nations Network’ Dr Tjanara Goreng Goreng and Dominic Wy Kanak, also oppose the voice.[91]

Pauline Hanson's One Nation opposes the Voice as party policy.[92]

The conservative lobby group Advance Australia opposes the Voice.[93]

Conservative academics Keith Windschuttle and David Flint oppose the Voice.[94] Flint dedicated an episode of his TV series "Save the Nation" to the topic in 2022.[94]

Professor Gary Foley, who co-founded the Aboriginal Tent Embassy opposes the voice.[95]

Public opinion

National

Research commissioned by From the Heart and conducted by the C|T Group in June 2020 shows that a majority of Australians support a constitutionally-enshrined voice to parliament, and that this support has increased 7 percent in three months, from 49 percent in March to 56 percent in June 2020. There were 2000 participants in the survey, who were asked, "If a referendum were held today, how would you vote on the proposal to change the Constitution to set up a new body comprising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people that gives advice to federal parliament on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander issues?". Only 17 percent said they would vote no, down 3 percent since March 2020.[96][97]

The ABC's Vote Compass survey has included questions about a voice to parliament in both its 2019 and 2022 editions. In 2019, 64% of voters agreed with the establishment of a voice while 22% disagreed. Of these, 37% strongly agreed, 27% somewhat agreed, 13% were neutral, 10% somewhat disagreed, and 12% strongly disagreed. The 2022 edition of Vote Compass found that support had grown to 73% while opposition declined to 16%: 48% strongly agreed, 25% somewhat agreed, 10% were neutral, 7% somewhat disagreed, and 9% strongly disagreed.[98]

| Graphical summary (2017–present) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| Date | Firm | Sample | Support | Oppose | Undecided |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-6 February 2023 | Essential | >1000 | 65% | 35% | — |

| 1-2 February 2023 | Newspoll | 1512 | 56% | 37% | 7% |

| 24 January 2023 | Resolve Strategic[99] | 3618 | 60% | 40% | — |

| 21 January 2023 | YouGov [100] | 46% | 30% | 24% | |

| 13 December 2022 | Essential[101] | 1075 | 63% | 37% | — |

| 9-12 December 2022 | Roy Morgan[102] | 1499 | 53% | 30% | 17% |

| 9-11 December 2022 | Freshwater Strategy[103] | 1209 | 50% | 26% | 24% |

| September 2022 | Resolve Strategic[104] | 3618 | 64% | 36% | — |

| August 2022 | JWS Research[105] | 1000 | 47% | 24% | 29%[a] |

| August 2022 | Essential[106] | 1075 | 65% | 35% | — |

| July 2022 | Australia Institute[107] | 1000 | 65% | 14% | 21% |

| June 2022 | Australia Institute[107] | 1000 | 58% | 16% | 26% |

| July 2021 | Essential[108] | 1099 | 66% | 19% | 15% |

| July 2020 | CT Group[109] | 2000 | 56% | 17% | 27% |

| February 2020 | CT Group[110] | 2000 | 49% | 20% | 31% |

| July 2019 | Essential[111] | 1097 | 70% | 18% | 12% |

| June 2019 | Essential[112] | 1079 | 66% | 21% | 13% |

| February 2018 | Essential[113] | 1028 | 68% | 21% | 11% |

| November 2017 | Essential[114] | 1025 | 45% | 16% | 39%[b] |

| June 2017 | Essential[115] | 1013 | 44% | 14% | 42%[c] |

- Notes

Subnational

New South Wales

| Graphical summary (2022–present) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| Date | Firm | Sample | Support | Oppose | Undecided |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| September 2022 | Resolve Strategic[116] | 1069 | 65% | 35 | — |

| 20 December 2022 | Roy Morgan[117] | 52% | 29% | 19% | |

| 21 January 2023 | YouGov[118] | 1069 | 46% | 30% | — |

| 24 January 2023 | Resolve Strategic[99] | 1069 | 58% | 42% | — |

Victoria

| Graphical summary (2022–present) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| Date | Firm | Sample | Support | Oppose | Undecided |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| September 2022 | Resolve Strategic[116] | 1069 | 64% | 36% | — |

| 20 December 2022 | Roy Morgan[117] | 55% | 28% | 17% | |

| 24 January 2023 | Resolve Strategic[99] | 1069 | 65% | 35% | — |

Queensland

| Graphical summary (2022–present) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| Date | Firm | Sample | Support | Oppose | Undecided |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| September 2022 | Resolve Strategic[116] | 1069 | 59% | 41% | — |

| 20 December 2022 | Roy Morgan[117] | 44% | 38% | 18% | |

| 24 January 2023 | Resolve Strategic[99] | 1069 | 56% | 44% | — |

Western Australia

| Graphical summary (2022–present) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| Date | Firm | Sample | Support | Oppose | Undecided |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| September 2022 | Resolve Strategic[116] | 1069 | 60% | 40% | — |

| 20 December 2022 | Roy Morgan[117] | 63% | 26% | 11% | |

| 24 January 2023 | Resolve Strategic[99] | 1069 | 61% | 39% | — |

South Australia

| Graphical summary (2022–present) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| Date | Firm | Sample | Support | Oppose | Undecided |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| September 2022 | Resolve Strategic[116] | 1069 | 71% | 29% | — |

| 20 December 2022 | Roy Morgan[117] | 54% | 33% | 13% | |

| 24 January 2023 | Resolve Strategic[99] | 1069 | 56% | 44% | — |

Tasmania

| Graphical summary (2022–present) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| Date | Firm | Sample | Support | Oppose | Undecided |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| September 2022 | Resolve Strategic[116] | 1069 | 73% | 27% | — |

| 20 December 2022 | Roy Morgan[117] | 68% | 24% | 8% | |

| 24 January 2023 | Resolve Strategic[99] | 1069 | 71% | 29% | — |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians

A 20-24 January 2023 poll surveyed 300 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians.

- 80% supported the Voice (57% "very sure", 21% "fairly sure", 2% "not really sure")

- 10% opposed

- 10% undecided

The question posed was "Do you support an alteration to the Australian Constitution that establishes a Voice to parliament for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people?", the poll was commissioned by The Uluru Dialogue group at University of New South Wales Law Centre, and conducted by polling company Ipsos. The sample was controlled for age, sex and location.[119]

State and territory voices

ACT Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Elected Body

The ACT Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Elected Body (ATSIEB) was established in 2008.[120]

First People's Assembly of Victoria

In November 2019, the First Peoples' Assembly of Victoria was first elected, consisting of 21 members representing Aboriginal Victorians, elected from five different regions in the state, and 10 members to represent each of the state's formally recognised traditional owner corporations (excluding the Yorta Yorta Nation Aboriginal Corporation, who declined to participate in the election process).[121] This body provides an Indigenous voice to the Victorian parliament.

First Nations Voice to Parliament (South Australia)

In May 2021, South Australian Premier Steven Marshall announced his government's intention to create the state's first Indigenous Voice to Parliament.[122] After the election of a state Labor government in 2022, new premier Peter Malinauskas pledged to implement this state-based voice to parliament, as well as restarting treaty talks and greater investment in areas affecting Aboriginal people in the state.[123] In July 2022 Dale Agius was appointed as the state's first Commissioner for First Nations Voice, with the role commencing in August and responsible for liaising with federal government. Kokatha elder Dr Roger Thomas would continue as Commissioner for Aboriginal Engagement for a further six months.[124]

In January 2023 the government secured the support of the Greens for a bill which would be debated in parliament later in the year. Kyam Maher, Attorney-General of South Australia and Minister for Aboriginal Affairs said that they expected to have the First Nations Voice to Parliament operational by the end of 2023.[125] The process would include the election of 40 people by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people enrolled to vote ore members specific to their geographic area, with 12 of these forming a statewide Voice, which would be entitled to address the parliament on any bill being debated.[126] An open letter was sent in early January to Agius and Maher by Native Title Services SA on behalf of most of the native title bodies, voicing some concerns about aspects of the model, saying the proposal would bypass established individual native title groups' voices. Maher said later that their concerns would be taken into consideration, and the bill would ensure the Voice would not impinge on what the groups do, and would ensure the existence of a formal structure to take into account their views.[127]

Stances of political parties

Summary

| Party | Stance | Notes and references | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Animal Justice | Support | [128] | |

| Democrats | Support | [129] | |

| Centre Alliance | Unknown | The party has not openly taken a stance on the issue, but does support the recognition of Indigenous Australians in the Constitution.[130] | |

| Christians | Ambiguous | [131] | |

| Communist | Support | [132] | |

| Country Liberal | Undecided | Same stance as the Liberal Party. In February 2023, it was reported that CLP may make a decision to oppose to Voice.[133][134] | |

| Democratic Labour | Oppose | ||

| Greens | Support | The party has a preference for truth telling and treaty processes to occur prior to the voice but have nonetheless backed the 'yes' campaign for the expected referendum on the voice. [135] The Greens also support proclamation of a republic and oppose Australia Day being celebrated on 26 January | |

| Justice | Oppose | Leader Derryn Hinch supports the recognition of Indigenous Australians and their history in the Constitution, but not a Voice to Parliament. However, Hinch also stated that members of the party would be allowed a conscience vote on the issue.[136] | |

| Katter's Australian | Ambiguous | Leader Bob Katter (who is the federal MP for the Division of Kennedy) has stated that the Voice to Parliament may not cover important issues faced by Indigenous Australians, instead proposing a designated Indigenous senator. However, he has given his support for a referendum on the matter.[137] Despite this, all three of the party's MPs in the Legislative Assembly of Queensland have requested more information from federal and state governments (a similar position to the Liberals) and have stated that they could possibly support Voice to Parliament. | |

| Labor | Support | Leader Anthony Albanese has given his support and pledged that a referendum would be held. | |

| Lambie | Unknown | ||

| Liberal | Undecided (supported in New South Wales and Tasmania) | Leader Peter Dutton has requested more information before his party gives support or opposition. Some members, however, openly have a stance on the issue. Federal members of the party's Tasmanian branch are currently divided on the issue.[138] Tasmania Premiere and New South Wales Premiere endorsed the Voice in a National Cabinet Meeting. [139][140] | |

| Liberal Democrats | Oppose | The party oppose the Voice.[141] | |

| Liberal National | Undecided | Same stance as the Liberal and National parties. | |

| National | Oppose (except in Western Australia) | The Nationals have stated that they oppose a Voice to Parliament, citing concerns that it would not be inclusive of regional areas. The Western Australian branch, however, supports the Voice.[142] | |

| One Nation | Oppose | One Nation opposes both a Voice to Parliament and a referendum on the subject.[143] | |

| Reason | Support | [144] | |

| Socialist Alliance | Support | [145] | |

| United Australia | Unknown | Its sole Senator Ralph Babet is opposed to the Voice.[146] | |

Independent parliamentarians

| Name | Stance | Notes and references | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kate Chaney | Support | [147] | |

| Zoe Daniel | Support | [148] | |

| Andrew Gee | Support | Gee defected from the National Party in December 2022, shortly after the party announced its opposition to the Voice. He cited a need to support the Voice as a key reason for leaving the party,[149] although party leader David Littleproud mentioned several disagreements that led to the decision.[150] | |

| Helen Haines | Support | [151] | |

| Dai Le | Neutral | As of January 2023, Le maintains a neutral position towards the Voice, claiming that it is not a priority for the culturally diverse communities in her electorate.[152] | |

| David Pocock | Support | [153] | |

| Monique Ryan | Support | [154] | |

| Sophie Scamps | Support | Scamps referred to the First Nations Voice to Parliament as a "generous invitation" in her first speech to Parliament in August 2022.[155] | |

| Allegra Spender | Support | [156] | |

| Zali Steggall | Support | [157] | |

| Lidia Thorpe | Oppose | When she was the Indigenous affairs spokeswoman of the Australian Greens, Thorpe expressed concern that the Voice was "unlikely to involve any meaningful transfer of power" as early as August 2022, instead calling for Treaty before Voice.[158] Thorpe defected from the Australian Greens in February 2023, in order to represent a movement for Australian Aboriginal sovereignty and campaign for a treaty between First Nations people and the Australian government.[159] | |

| Kylea Tink | Undecided | Tink interviewed proponent of the Voice Thomas Mayor in May 2022, and in January 2023 she opposed legislation if the Voice referendum does not pass, but she has not publicly announced her position.[160][161] | |

| Andrew Wilkie | Support | [162] | |

Stances of former Prime Ministers

When serving as Prime Minister Scott Morrison has previously proposed a version of the Voice,[163] but ruled out a referendum on Albanese's proposal.[164] It is unknown if his opinion has changed since.

In August 2022, Malcolm Turnbull stated that despite his previous concerns, he would now vote in favour of Albanese's proposal,[165]

Tony Abbott has openly given his opposition the Voice.[166][167][168] He has since become an outspoken critic of the Voice.

Julia Gillard has not yet spoken on the issue.

Kevin Rudd also supports the Voice to Parliament, slamming Tony Abbott's stance on the issue as "wrong".[169]

Paul Keating strongly supports the Voice, saying that the Albanese government should not postpone a referendum on the issue and should hold it in its first term.[170]

See also

- Assembly of First Nations (Canada)

- Australian Aboriginal sovereignty

- Bureau of Indian Affairs (United States)

- Indigenous treaties in Australia

- Māori politics

References

- ^ a b Wahlquist, Calla (26 October 2017). "Indigenous voice proposal 'not desirable', says Turnbull". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 29 October 2017 suggested (help) - ^ "Researchers demystify the secrets of ancient Aboriginal migration across Australia". ABC. 12 February 2023. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "An ancient Australian connection to India?". The Conversation. 10 March 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "Researchers demystify the secrets of ancient Aboriginal migration across Australia". ABC. 30 April 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "Proof of mystery settlement of Aboriginal Australians and Indonesians found in an Italian library". ABC News. 10 February 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Mundine, Warren (1 February 2023). "Voice will fail like four previous attempts at national Aboriginal body". Sky News Australia. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ "National Museum of Australia - Indigenous Australians' right to vote". National Museum of Australia. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 9 April 2020 suggested (help) - ^ "Electoral Milestone: Timetable for Indigenous Australians". Australian Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 6 January 2008.

- ^ "History of the Indigenous Vote". Australian Electoral Commission. August 2006. Archived from the original on 17 February 2011.

- ^ "Indigenous parliamentarians, federal and state: a quick guide". Parliament of Australia. 11 July 2017. Archived from the original on 12 July 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ Remeikis, Amy (24 July 2022). "The 47th parliament is the most diverse ever – but still doesn't reflect Australia". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 19 November 2022. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ Quentin, Beresford (2007). Rob Riley : an aboriginal leader's quest for justice. Aboriginal Studies Press. ISBN 978-0-85575-502-7. OCLC 220246007.

- ^ "History of National Representative Bodies | National Congress of Australia's First Peoples". 14 April 2019. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ Levin, Michael D. (31 December 1993), "Chapter 9. Ethnicity and Aboriginality: Conclusions", Ethnicity and Aboriginality, University of Toronto Press, pp. 168–180, doi:10.3138/9781442623187-012, ISBN 9781442623187, retrieved 5 January 2022

- ^ "The end of ATSIC and the future administration of Indigenous affairs". Parliament of Australia. 9 August 2004. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ Parliament of Australia. Select Committee on the Administration of Indigenous Affairs (March 2005). "Chapter 4: Representation". After ATSIC: Life in the mainstream?. Commonwealth of Australia. ISBN 0-642-71501-7.

- ^ a b "The Process". Aboriginal and Torre Strait Islander Voice. Archived from the original on 17 October 2022. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ "Our Future in Our Hands - Community Guide | Australian Human Rights Commission". humanrights.gov.au. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ "2009 Media Release: New National Congress of Australia's First Peoples announced". humanrights.gov.au. 22 November 2009. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ "Readings 15:National Congress of Australia's First Peoples: Working with Indigenous Australians". www.workingwithindigenousaustralians.info. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ Coggan, Maggie (29 July 2019). "Australia's largest Indigenous organisation forced to shut up shop". Pro Bono Australia. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020.

- ^ Cassandra, Morgan (17 October 2019). "Closure of Aboriginal organisation means loss of First People's voice: former co-chairman". The Canberra Times. Archived from the original on 9 February 2023. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ Noel Pearson (September 2014). "A Rightful Place: Race, recognition and a more complete commonwealth". Quarterly Essay (55).

- ^ "In office – Harold Holt – Australia's PMs – Australia's Prime Ministers". Primeministers.naa.gov.au. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ Taylor, Russell. "Indigenous Constitutional Recognition: The 1967 Referendum and Today". Parliament of Australia. Archived from the original on 19 November 2021. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 19 November 2022 suggested (help) - ^ Chrysanthos, Natassia (27 May 2019). "What is the Uluru Statement from the Heart?". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 5 July 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ Expert Panel on Constitutional Recognition of Indigenous Australians (January 2012). Recognising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples in the Constitution : Report of the Expert Panel. Commonwealth of Australia. ISBN 9781921975295. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- ^ Balogh, Stefanie (13 November 2013). "Tony Abbott dreams of an indigenous PM". The Australian. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013.

- ^ "Final Report". Parliament of Australia. Archived from the original on 30 November 2022. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ Gordon, Michael (25 June 2015). "Time to end the constitution's silence on Australia's first people: report". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 19 November 2019. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 19 November 2022 suggested (help) - ^ Worsley, Ben (6 July 2015). "Indigenous referendum: Australians invited to join community conferences on recognition vote". ABC News (Australia). Archived from the original on 8 August 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ "Commissioner Gooda appointed to Referendum Council". Australian Human Rights Commission. 7 December 2015. Archived from the original on 30 November 2022. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ Discussion Paper on Constitutional Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples (PDF). Australia: Commonwealth of Australia. 2017. p. 11. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ "Uluru Statement from the Heart". referendumcouncil.org.au. Referendum Council. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- ^ Final Report of the Referendum Council (PDF). Commonwealth of Australia. 2017. p. 15. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 March 2018.

- ^ corporateName=Commonwealth Parliament; address=Parliament House, Canberra. "Joint Select Committee on Constitutional Recognition Relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples". www.aph.gov.au. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia. Joint Select Committee on Constitutional Recognition relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples (November 2018). Final report. Commonwealth of Australia. ISBN 978-1-74366-926-6. Retrieved 18 July 2020. PDF

- ^ "2. Designing a First Nations Voice". www.aph.gov.au. Archived from the original on 14 December 2022. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ "A voice for Indigenous Australians". Ministers Media Centre. 30 October 2019. Archived from the original on 7 March 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ Synot, Eddie (30 October 2019). "Ken Wyatt's proposed 'voice to government' marks another failure to hear Indigenous voices". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 31 October 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ a b Grattan, Michelle (29 October 2019). "Proposed Indigenous 'voice' will be to government rather than to parliament". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 30 October 2019. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ a b Allam, Lorena (1 February 2020). "Man in the middle: Ken Wyatt on being caught between the Uluru statement and his party". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ "Voice Co-Design Senior Advisory Group". Ministers Media Centre. 8 November 2019. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ Remeikis, Amy (8 November 2019). "Chris Kenny added to group working on Indigenous voice to parliament". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 November 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ Wellington, Shahni (13 November 2019). "First meeting held by senior body for Indigenous Voice to government". NITV. Special Broadcasting Service. Archived from the original on 8 July 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ Allam, Lorena (28 January 2020). "Josephine Cashman sacked from Indigenous advisory body after letter published by Andrew Bolt". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ Archibald-Binge, Ella (28 January 2020). "Businesswoman ousted from advisory group after Andrew Bolt claim". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ Latimore, Jack (28 January 2020). "Letter revealed to contain paragraphs lifted from academic papers and websites". SBS News. NITV. Archived from the original on 1 March 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ "National Co-design Group". Indigenous Voice. Archived from the original on 18 July 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ Fryer, Brooke (4 March 2020). "Newly announced advisory body tasked with giving communities a voice". NITV. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ "Indigenous voice Local and Regional Co-Design Group announced". National Indigenous Australians Agency. 4 March 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ "First Meeting of the Local & Regional Co-Design Group". National Indigenous Australians Agency. 19 March 2020. Archived from the original on 9 April 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ Doran, Matthew (15 November 2020). "Minister Ken Wyatt wants Indigenous voice to government to pass parliament before next election". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ "Indigenous voice to parliament to have no veto power under interim plans". The Guardian. 9 January 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ "Indigenous Voice to parliament will get no veto power under interim proposal". SBS News. 9 January 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ Lysaght, Gary-Jon (24 March 2021). "Indigenous Voice to Parliament to include regional voices to address local issues". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Langton, Marcia; Calma, Tom (July 2021). Indigenous Voice Co-design Process – Final Report to the Australian Government (PDF). ISBN 978-1-925364-72-9.

- ^ Tim Rowse (10 March 2022). "Review of the The Indigenous Voice Co-design Process: Final Report to the Australian Government". Australian Policy and History Network, Deakin University.

- ^ Langton & Calma 2021, ch. 2.8 "Functions", p. 148.

- ^ Langton & Calma 2021, p. 7.

- ^ Martin, Sarah (19 November 2021). "Indigenous voice to parliament legislation 'imminent', Coalition sources say". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ Brennan, Bridget (22 May 2022). "Debate over Indigenous Voice to Parliament may define Anthony Albanese's government". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ a b "Address to Garma Festival | Prime Minister of Australia". www.pm.gov.au. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ Ella Archibald-Binge (29 July 2022). "Prime Minister to announce Australia's first referendum in 20 years at Garma Festival. Here's what you might be asked". ABC News. Australia.

- ^ "Anthony Albanese reveals 'simple and clear' wording of referendum question on Indigenous voice". The Guardian Australia. 29 July 2022.

- ^ Langton & Calma 2021, ch. 2.8. "Role of the National Voice, p. 148.

- ^ "Referendum (Machinery Provisions) Act 1984", Schedule 1, Forms

- ^ George Williams (8 August 2022). "Labor should take a step back in voice debate". The Australian. p. 11.

- ^ a b "First meetings of Referendum Working Group & Referendum Engagement Group". Prime Minister of Australia. 29 September 2022. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

Text has been copied from this source, which is available under a Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence.

Text has been copied from this source, which is available under a Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence.

- ^ "Woodford Folk Festival | Prime Minister of Australia". www.pm.gov.au. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ "'Momentum is growing': Anthony Albanese promises to deliver Voice referendum by December 2023". ABC News. 28 December 2022. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ "Our People – The Uluru Statement". From The Heart. 15 March 2020. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ Collard, Sarah (25 August 2022). "Don't let 'low bar politics' hold back Indigenous voice, advocate to say in Lingiari lecture". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- ^ a b Cassidy, Caitlin (9 May 2022). "Australians urged to back Indigenous voice to parliament in History is Calling campaign". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ Riches, Caroline (25 September 2022). "'This is your business': Uluru Statement leaders launch ad asking Australians to give them a voice". SBS News. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ Former deputy prime minister John Anderson joins group spearheading “no” campaign on the Voice, The Conversation, Jan 30, 2023

- ^ "Recognise a Better Way | Home". www.recogniseabetterway.org.au.

- ^ Examining the case for the voice – an argument against, Ian Callinan, The Australian, Dec 17, 2022

- ^ "Nationals will oppose Indigenous Voice to Parliament". www.9news.com.au. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ "Peter Dutton's approach to referendum on Indigenous voice straight from John Howard playbook | Paul Karp". the Guardian. 13 January 2023. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- ^ Beyond Belief - Rethinking the Voice to Parliament; Edited by Peter Kurti and Nyunggai Warren Mundine; ISBN 9781925138795

- ^ Vic Liberals will be asking 'what message' was lost with the people: Joyce; youtube.com; Nov 28, 2022

- ^ Howard’s sway: the former PM speaks out on the voice; The Australian; 19 November 2022

- ^ Pass or fail, this referendum will surely leave us worse off; The Australian; Nov 4, 2022

- ^ "Nationals to oppose Indigenous Voice to Parliament". ABC News. 28 November 2022. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ < "Split in Nationals over Indigenous Voice to Parliament as Andrew Gee breaks ranks". ABC. 30 November 2022.

- ^ Greens Senator Lidia Thorpe attacks Voice referendum; smh.com.au; September 1, 2022

- ^ Lidia Thorpe wants to shift course on Indigenous recognition. Here’s why we must respect the Uluru Statement; theconversation.com; 8 July 2020

- ^ Kolovos, Benita; Karp, Paul (6 February 2023). "Lidia Thorpe quits Greens party to pursue black sovereignty". The Guardian.

- ^ "What is 'black sovereignty' and how does it conflict with the Voice?". ABC News. 6 February 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ Butler, Josh; Kolovos, Benita (8 February 2023). "Greens' First Nations conveners side with Lidia Thorpe and say they do not support voice to parliament". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ "One Nation to lead NO case on voice". Pauline Hanson's One Nation. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ^ "Sign this open letter to tell Anthony Albanese and Peter Dutton". Advance.

- ^ a b "Keith Windschuttle: The Voice: Break-up of Australia? - Save the Nation 2022". ADH TV. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ Hall, Bianca (26 January 2023). "Division over Voice as huge crowd turns out for Invasion Day rally". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ Wellington, Shahni (15 July 2020). "'Hugely encouraging': Voice to Parliament advocates boosted by poll". NITV. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ "Poll Shows Strong Rise in Support for Constitutional Change to Create Indigenous Voice to Parliament". From The Heart. 15 July 2020. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ "Vote Compass data finds most Australians support Indigenous Voice to Parliament – and it has grown since the last election". ABC News. Australia. 4 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g Crowe, David (23 January 2023). "Support for Voice slips as voters await more detail". The Age.

- ^ https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/nsw/whats-it-mean-majority-of-voters-baffled-by-the-voice-poll/news-story/3640571d1069f12180a8714a99a55b61

- ^ "The Essential Report: 13 December 2022". Essential.

- ^ "53% of Australians would vote "Yes" to establish an 'Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice to Parliament'". Roy Morgan. 20 December 2022.

- ^ "AFR / Freshwater Strategy polling on 'The Voice'". Freshwater Strategy. 20 December 2022.

- ^ Sydney Morning Herald (26 September 2022). "Voters back the Voice – but there's doubt over what they're backing".

- ^ Australian Financial Review (29 August 2022). "Voters are very confused over Indigenous Voice: survey".

- ^ Essential (9 August 2022). "The Essential Report: 09 August 2022".

- ^ a b Australia Institute (31 July 2022). "Polling – Voice to Parliament in the Constitution".

- ^ Essential (6 July 2021). "Support and priority of Indigenous Issues".

- ^ Special Broadcasting Service (16 September 2020). "'Hugely encouraging': Voice to Parliament advocates boosted by poll".

- ^ Sydney Morning Herald (30 May 2020). "Keeping hope alive: the push to revive the Statement from the Heart".

- ^ The Guardian (12 July 2019). "Essential poll: majority of Australians want Indigenous recognition and voice to parliament". TheGuardian.com.

- ^ Essential (27 June 2019). "The Essential Report" (PDF).

- ^ Essential (27 February 2018). "The Essential Report" (PDF).

- ^ Essential (7 November 2017). "Uluru Statement".

- ^ Essential (6 June 2017). "Uluru Statement".

- ^ a b c d e f Crowe, David (25 September 2022). "Voters back the Voice – but there's doubt over what they're backing". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^ a b c d e f https://www.roymorgan.com/findings/53-of-australians-would-vote-yes-to-establish-an-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-voice-to-parliament

- ^ "YouGov Indigenous voice poll: yes 46, no 30 in NSW (open thread) – The Poll Bludger". www.pollbludger.net.

- ^ "'Not going to chuck the towel in': Voice champion Pat Anderson undaunted by criticism at Invasion Day rallies". Sydney Morning Herald. 27 January 2023. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ "Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander - Elected Body". Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ Dunstan, Joseph (5 November 2019). "Victorian Aboriginal voters have elected a treaty assembly. So what's next?". ABC News. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ Jenkins, Shannon (7 May 2021). "SA premier flags plan for Indigenous Voice to parliament". The Mandarin. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ Smith, Douglas (23 March 2022). "What SA's new govt wants to achieve in Aboriginal affairs". NITV. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ "Next steps in implementing the Uluru Statement". Premier of South Australia. 4 July 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ Katsaras, Jason (19 January 2023). "Green light for SA's Indigenous Voice to Parliament". InDaily. Retrieved 20 January 2023.

- ^ Manfield, Evelyn (19 January 2023). "South Australia set to get First Nations' Voice to Parliament after proposal wins Greens' support". ABC News. Retrieved 20 January 2023.

- ^ Katsaras, Jason (20 January 2023). "'Going backwards': SA native title bodies raise Voice concerns". InDaily. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ "First Nations". Animal Justice Party Australia.

- ^ "Standing with First Nations - our plan". Australian Democrats. 10 May 2022.

- ^ "Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders". Centre Alliance.

- ^ "Jesus, the real HOPE of the world (and Australia's Parliament) - Australian Christians". australianchristians.org.au. 12 December 2022.

- ^ "Indigenous rights".

- ^ https://www.ntnews.com.au/business/nt-business/senator-jacinta-price-predicts-country-liberal-party-will-oppose-voice-to-parliament/news-story/60124d1f25cbde478e6709090c5f631c

- ^ https://www.adelaidenow.com.au/news/northern-territory/senator-jacinta-price-predicts-country-liberal-party-will-oppose-voice-to-parliament/news-story/60124d1f25cbde478e6709090c5f631c

- ^ "Greens to back Voice". Australian Greens. 6 February 2023.

- ^ Hinch, Derryn (26 January 2023). "Derryn Hinch's view on The Voice to Parliament".

- ^ Clarke, Harry (30 November 2022). "Bob Katter weighs in on proposed Voice to Parliament". Country Caller.

- ^ "Federal Liberal ranks split on Voice to Parliament | NIT".

- ^ Allam, Lorena; Collard, Sarah (3 February 2023). "PM, state and territory leaders formally back Indigenous voice to parliament with statement of intent". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 February 2023. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ Finn, McHugh (3 February 2023). "Liberal premiers break ranks with Peter Dutton as states back Voice to Parliament". SBS News. Archived from the original on 8 February 2023. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ "Silence an Indigenous Voice, LibDems say". Liberal Democrats.

- ^ "Split emerges within Nationals over Indigenous Voice". skynews. 29 November 2022.

- ^ "Aboriginal Voice to Parliament". Pauline Hanson's One Nation.

- ^ "First Nations Self Determination". Reason Australia.

- ^ "Voice to Parliament has to be more than a token gesture | Socialist Alliance". socialist-alliance.org.

- ^ "Voice of racism". The Spectator Australia. 25 January 2023.

- ^ "INCLUSIVE COMMUNITIES". Kate Chaney.

- ^ "Recognition for First Nations Australians".

- ^ Karp, Paul (23 December 2022). "Nationals MP Andrew Gee quits party citing its opposition to Indigenous voice" – via The Guardian.

- ^ https://www.news.com.au/finance/work/leaders/david-littleproud-says-andrew-gee-didnt-quit-the-nationals-because-of-voice/news-story/6360de5d872e61544fa2b5ff05831158

- ^ "Where I stand on..." Helen Haines MP - Independent Federal Member for Indi.

- ^ "Ethnic voters loom as crucial to success of Voice vote". Australian Financial Review. 23 January 2023.

- ^ "Senator Pocock's First Speech". David Pocock.

- ^ "Policy Priorities". Dr Monique Ryan for Kooyong.

- ^ "Dr Sophie Scamps' first speech in Parliament". Dr Sophie Scamps.

- ^ "Other Policies". Allegra Spender.

- ^ "Where does Zali stand on..." Zali Steggall.

- ^ "'On the table': Greens want treaty before backing Voice to Parliament". The Canberra Times. 9 August 2022.

- ^ "What is 'black sovereignty' and how does it conflict with the Voice?". 6 February 2023 – via www.abc.net.au.

- ^ "MOVING FORWARD WITH THE ULURU STATEMENT - THOMAS MAYOR & KYLEA TINK" – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ https://twitter.com/KyleaTink/status/1617319047158435842

- ^ "Publications". Andrew Wilkie.

- ^ Wiles, Paul (18 February 2022). "PM Scott Morrison shares his version of the "Voice to Parliament." Mparntwe Alice Springs, February 18 - 2022".

- ^ "Election 2022: Scott Morrison rules out referendum on Indigenous Voice if re-elected". amp.smh.com.au.

- ^ Malcolm Turnbull (15 August 2022). "I will be voting yes to establish an Indigenous voice to parliament". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- ^ "Voice to Parliament wrong in principle, bad in practice: Tony Abbott". skynews. 23 December 2022.

- ^ "Tony Abbott accuses tech of censoring 'no' campaign". skynews. 4 January 2023.

- ^ "Tony Abbott tells CPAC an Indigenous voice to parliament would promote 'discrimination' | Tony Abbott | The Guardian". amp.theguardian.com.

- ^ "Kevin Rudd says Tony Abbott is wrong on the Voice to parliament". amp.smh.com.au.

- ^ "Labor must not betray Indigenous voters by delaying voice to parliament, Keating and Pearson say | Indigenous Australians | The Guardian". amp.theguardian.com.

Further reading

- Davis, Megan (17 February 2020). "Constitutional recognition for Indigenous Australians must involve structural change, not mere symbolism". The Conversation.

- Davis, Megan (24 January 2021). "Toxicity swirls around January 26, but we can change the nation with a Voice to parliament". The Conversation.

- Seo, Bo (10 July 2019). "The Indigenous voice to Parliament explained". Australian Financial Review.