Egyptian hieroglyphs

| Egyptian hieroglyphs | |

|---|---|

| Script type | Alternative

abjad, logographic and ideographic |

Time period | 3200 BC – 400 AD |

| Direction | Right-to-left script, left-to-right |

| Languages | Egyptian language |

| Related scripts | |

Child systems | Hieratic |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Egyp (050), Egyptian hieroglyphs |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Egyptian Hieroglyphs |

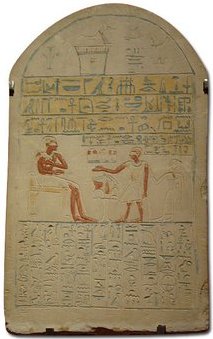

Egyptian hieroglyphs (Sometimes called Hieroglyphics) was a writing system used by the Ancient Egyptians, that contained a combination of logographic, alphabetic, and ideographic elements. Cartouches were also used by the Egyptians. The variety of brush-painted hieroglyphs used on papyrus and (sometimes) on wood for religious literature is known as cursive hieroglyphs; this should not be confused with hieratic. 3100 B.C - 400 A.D.

The word hieroglyph comes from the Greek ἱερογλυφικά (hieroglyphiká); the adjective hieroglyphic, as well as related words such as ἱερoγλυφος (hieroglyphos 'one who writes hieroglyphs', from ἱερός (hierós 'sacred') and γλύφειν (glýphein 'to carve' or 'to write', see glyph). Hieroglyphs themselves, were called τὰ ἱερογλυφικά (γράμματα) (tà hieroglyphiká (grámmata), 'engraved characters') on monuments (such as stelae, temples and tombs). The word hieroglyph has come to be used for the individual hieroglyphic characters themselves. While "hieroglyphics" is commonly used, it is discouraged by Egyptologists.

History and evolution

Hieroglyphs emerged from the preliterate artistic traditions of Egypt. For example, symbols on Gerzean pottery from circa 4000 BC resemble hieroglyphic writing.[1] For many years the earliest known hieroglyphic inscription was the Narmer Palette, found during excavations at Hierakonpolis (modern Kawm al-Ahmar) in the 1890s, which has been dated to circa 3200 BC. However, in 1998 a German archeological team under Günter Dreyer excavating at Abydos (modern Umm el-Qa'ab) uncovered tomb U-j of a Predynastic ruler, and recovered three hundred clay labels inscribed with proto-hieroglyphs, dating to the Naqada IIIA period of the 33rd century BC.[2][3] The first full sentence written in hieroglyphs so far discovered was found on a seal impression found in the tomb of Seth-Peribsen at Umm el-Qa'ab in Abydos, which dates from the Second Dynasty. In the era of the Old Kingdom, the Middle Kingdom and the New Kingdom, about 700 hieroglyphs existed. By the Graeco-Roman period, they numbered more than 5,000.[4]

Hieroglyphs consist of three kinds of glyphs: phonetic glyphs, including single-consonant characters that functioned like an alphabet; logographs, representing morphemes; and determinatives, or ideograms, which narrowed down the meaning of a logographic or phonetic words.

As writing developed and became more widespread among the Egyptian people, simplified glyph forms developed, resulting in the hieratic (priestly) and demotic (popular) scripts. These variants were also more suited than hieroglyphs for use on papyrus. Hieroglyphic writing was not, however, eclipsed, but existed along side the other forms, especially in monumental and other formal writing. The Rosetta Stone contains parallel texts in hieroglyphic and demotic writing.

Hieroglyphs continued to be used under Persian rule (intermittent in the 6th and 5th centuries BC), and after Alexander's conquest of Egypt, during the ensuing Macedonian and Roman periods. It appears that the misleading quality of comments from Greek and Roman writers about hieroglyphs came about, at least in part, as a response to the changed political situation. Some believe that hieroglyphs may have functioned as a way to distinguish 'true Egyptians' from the foreign conquerors. Another reason may be the refusal to tackle a foreign culture on its own terms which characterized Greco-Roman approaches to Egyptian culture generally. Having learned that hieroglyphs were sacred writing, Greco-Roman authors imagined the complex but rational system as an allegorical, even magical, system transmitting secret, mystical knowledge.

By the fourth century, few Egyptians were capable of reading hieroglyphs, and the myth of allegorical hieroglyphs was ascendant. Monumental use of hieroglyphs ceased after the closing of all non-Christian temples in AD 391 by the Roman Emperor Theodosius I; the last known inscription is from a temple far to the south not long after 391.

Decipherment of hieroglyphic writing

In the fifth century appeared the Hieroglyphica of Horapollo, a spurious explanation of almost 200 glyphs. Authoritative yet largely false, the work was a lasting impediment to the decipherment of Egyptian writing. Whereas earlier scholarship emphasized Greek origin of the document, more recent work has recognized remnants of genuine knowledge, and casts it as an attempt by an Egyptian intellectual to rescue an unrecoverable past. The Hieroglyphica was a major influence on Renaissance symbolism, particularly the emblem book of Andrea Alciato, and including the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili of Francesco Colonna.

Various modern scholars attempted to decipher the glyphs over the centuries, notably Johannes Goropius Becanus in the 16th century and Athanasius Kircher in the 17th, but all such attempts met with failure. The real breakthrough in decipherment began in the early 1800s by scholars as Silvestre de Sacy, Akerblad and Thomas Young. Finally, Jean-François Champollion made the complete decipherment. The discovery in 1799 of the Rosetta Stone by Napoleon's troops (during Napoleon's Egyptian invasion) provided the critical information which allowed Champollion to discover the nature of the script by the 1820s:

It is a complex system, writing figurative, symbolic, and phonetic all at once, in the same text, the same phrase, I would almost say in the same word[5]

This was a major triumph for the young discipline of Egyptology.

Hieroglyphs survive today in two forms: Directly, through half a dozen Demotic glyphs added to the Greek alphabet when writing Coptic; and indirectly, as the inspiration for the original alphabet that was ancestral to nearly every other alphabet ever used, including the Roman alphabet.

Writing system

Visually hieroglyphs are all more or less figurative: they represent real or imaginary elements, sometimes stylized and simplified, but all generally perfectly recognizable in form. However, the same sign can, according to context, be interpreted in diverse ways: as a phonogram (phonetic reading), as a logogram, or as an ideogram (semagram; "determinative") (semantic reading). The determinative was not read as a phonetic constituent, but facilitated understanding by differentiating the word from its homophones.

Phonetic reading

Most hieroglyphic signs are phonetic in nature, meaning the sign is read independent of its visual characteristics (according to the rebus principle where, for example, the picture of an eye could stand for the English words eye and I [the first person pronoun]). Phonograms are formed, whether with one consonant (signs called mono- or uniliteral) or by two consonants (biliteral signs) or by three (triliteral signs). The twenty-four uniliteral signs make up the so-called hieroglyphic alphabet. Since Egyptian hieroglyphic writing does not normally indicate vowels, in contrast, for example, to cuneiform, it could perhaps be argued that it is a variety of abjad.

Thus, hieroglyphic writing representing a duck is read in Egyptian as sȝ, the consonants of the word for this animal. Nevertheless, it is is also possible to use the hieroglyph of the duck without a link to the meaning in order to represent the phonemes sȝ, independent of any vowels which could accompany these consonants, and in this way write the words: sȝ, "son," or when complemented by other signs detailed further in the text, sȝ, "keep, watch"; and sȝṯ.w, "hard ground":

| |

– the character sȝ;

| |

– the same character used only in order to signify, according to the context, "duck" or, with the appropriate determinative, "son", two words having the same consonants; the meaning of the little vertical stroke will be explained further on:

| |

– the character sȝ as used in the word sȝw, "keep, watch"

Like the Arabic script, vowels were not written in Egyptian hieroglyphs. Therefore in modern transcriptions an e is added between consonants to aid in their pronunciation. For example, nfr "good" is typically written nefer. This does not reflect Egyptian vowels, which are obscure, but is merely a modern convention. Likewise, the ȝ and ʾ are commonly transliterated as a, as in Ra.

Hieroglyphs are written from right to left, from left to right, or from top to bottom, the usual direction being from right to left. The reader must consider the direction in which the asymmetrical hieroglyphs are turned in order to determine the proper reading order. For example, when human and animal hieroglyphs face to the right (i.e., they look right), they must be read from right to left, and vice versa, the idea being that the hieroglyphs face the beginning of the line.

Like many ancient writing systems, words are not separated by blanks or by punctuation marks. However, certain hieroglyphs appear particularly commonly at the end of words making it possible to readily distinguish words.

Uniliteral signs

The Egyptian hieroglyphic script contained 24 uniliterals (symbols that stood for single consonants, much like English letters). It would have been possible to write all Egyptian words in the manner of these signs, but the Egyptians never did so and never simplified their complex writing into a true alphabet.[6]

Each uniliteral glyph once had a unique reading, but several of these fell together as Old Egyptian developed into Middle Egyptian. For example, the folded-cloth glyph seems to have been originally an /s/ and the door-bolt glyph a /θ/ sound, but these both came to be pronounced as /s/ as the /θ/ sound was lost. A few uniliterals first appear in Middle Egyptian texts.

Besides the uniliteral glyphs, there are also the biliteral and triliteral signs, to represent a specific sequence of two or three consonants in the language.

Phonetic complements

Egyptian writing is often redundant: in fact, it happens very frequently that a word might follow several characters writing the same sounds, in order to guide the reader. For example, the word nfr, "beautiful, good, perfect", was written with a unique triliteral which was read nfr;

| |

However, it is considerably more common to add to this triliteral the uniliterals for f and r. The word is thus written as nfr+f+r but one reads it merely as nfr.

The two alphabetic characters are adding clarity to the spelling of the preceding triliteral hieroglyph.

Redundant characters accompanying biliteral or triliteral signs are called phonetic complements. They are sometimes (rarely) placed in front of the sign, after the sign (as a general rule) or they even frame it, appearing both before and after. Ancient Egyptian scribes consistently avoided leaving large areas of blank space in their writing, and might add additional phonetic complements or sometimes even invert the order of signs if this would result in a more aesthetically pleasing appearance (good scribes attended to the artistic (and even religious) aspects of the hieroglyphs, and would not simply view them as a communication tool). Various examples of the use of phonetic complements can be seen below:

– mdw +d +w (the complementaries are placed after the sign) → it reads mdw, "tongue"

– ḫ +p +ḫpr +r +j (the complementaries frame the triliteral sign) → it reads ḫpr.j, "Khepri".

Notably, phonetic complements were also used to allow the reader to differentiate between signs which are homophones, or which don't always have a unique reading. For example, "the seat,"

– This can be read st, ws and ḥtm, according to the word in which it is found. The presence of phonetic complements—and of the suitable determinative—allows us to know which reading will follow.

- 1st Reading: st –

– st, written st+t ; the last character is the determinative of "the house" or that which is found there, "seat, throne, place".

– st (written st+t ; the "egg" determinative is used for female personal names in some periods), "Isis",

- 2nd Reading: ws –

wsjr (written ws+jr, with, as a phonetic complement, "the eye", which is read jr, following the determinative of "god"), "Osiris".

- 3rd Reading: ḥtm –

ḥtm.t (written ḥ+ḥtm+m+t, with the determinative of "the jackal"), a kind of wild animal,

ḥtm (written ḥ+ḥtm+t, with the determinative of the flying bird), "to disappear".

Finally, it sometimes happens that the pronunciation of words might be changed because of their connection to Ancient Egyptian: in this case, it is not rare for writing to adopt a compromise in notation, the two readings being indicated jointly. For example, the adjective bnj, "sweet" became bnr. In Middle Egyptian, one can write

| |

bnrj (written b+n+r+i, with determinative) which is fully read as bnr, the j not having been saved except in order to keep a written connection with the ancient word (in the same fashion as the English language words through, knife, or victuals, which are no longer read the way they are written.)

nouns; they are always accompanied by a mute vertical stroke indicating their status as a logogram (the usage of a vertical stroke is further explained below); in theory, all hieroglyphs would have the ability to be used as logograms. Logograms can be accompanied by phonetic complements. Here are some examples:

| |

rˁ, "sun"

| |

pr, "house"

| |

swt, "reed" - the t is the phonetic complement.

| |

ḏw, "mountain", etc

In some cases, the semantic connection is indirect (metonymic or metaphoric):

| |

nṯr, "god" ; the character in fact represents a temple flag (standard)

| |

bȝ, " bâ" (soul) ; the character is the traditional representation of a "bâ", a bird with a human head

| |

dšr, "flamingo"; the corresponding phonogram means "red", and the bird is associated by metonymy with this colour.

Determinatives

Determinatives or semagrams are placed at the end of the word. These mute characters serve to clarify what the word is about, as homophonic glyphs are common. If a similar procedure existed in English, words with the same spelling would be followed by an index which would not be read but which would fine-tune the meaning: "retort [chemistry]" and "retort [rhetoric]" would thus be distinguished.

A number of determinatives exist: divinities, humans, parts of the human body, animals, plants, etc. Certain determinatives possess a literal meaning and a figurative meaning. For example, a roll of papyrus,

| |

is used to define "books," but also abstract ideas. The determinative of the plural is a shortcut to signal three occurrences of the word, that is to say, its plural (since the Egyptian language was familiar with a dual, sometimes indicated by two strokes). This special character is explained below.

Here are several examples of the use of determinatives borrowed from the book, Je lis les hiéroglyphes ("I am reading hieroglyphics") by Jean Capart, which illustrate their importance:

| |

nfrw (w and the three strokes are the marks of the plural: [literally] "the beautiful young people", that is to say, the young military recruits. The word has as a determinative:

| |

The determinative is one of babies and children.

| |

nfr.t (.t is here the suffix which forms the feminine): "the nubile young woman", with

| |

as the determinative of the woman;

| |

nfrw (the tripling of the character serving to express the plural, flexional ending w) : "foundations (of a house)", with the house as a determinative,

| |

;

| |

nfr : "clothing," where

| |

is the determinative for lengths of cloth;

| |

nfr : "wine" or "beer,"

| |

with a jug as the determinative.

All these words have a meliorative connotation: "good, beautiful, perfect." A recent dictionary, the Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian by Raymond A. Faulkner, gives some twenty words which are read nfr or which are formed from this word—proof of the extraordinary richness of the Egyptian language.

Additional signs

Cartouche

Rarely, the names of gods are placed within a cartouche; the two last names of the sitting king are always placed within a cartouche:

| |

jmn-rˁ, "Amon-Rê " ;

| |

qrwjwȝpdrȝ.t, "Cleopatra."

Filling stroke

A filling stroke is used in order to end a quad which would be incomplete without it.

Signs joined together

Some signs are the contraction of several others. These signs have, however, a function and existence of their own: for example, a forearm where the hand holds a scepter is used as a determinative for words meaning "to direct, to drive" and their derivatives.

Doubling

The doubling of a sign indicates its dual; the tripling of a sign indicates its plural.

Grammatical signs

- The vertical stroke, indicating the sign is an ideogram;

- The two strokes of the "dual" and the three strokes of the "plural";

- The direct notation of flexional endings, for example:

| |

Spelling

The idea of standardized orthography—"correct" spelling—in Egyptian is much looser than in modern languages. In fact, one or several variants exist for almost every word. One finds:

- Redundancies;

- Omission of graphemes, which are ignored whether they are intentional or not;

- Substitutions of one grapheme for another, such that it is impossible to distinguish a "mistake" from an "alternate spelling";

- Errors of omission in the drawing of signs, much more problematic when the writing is cursive: hieratic writing, but especially demotic, where the schematization of the signs is extreme.

However, many of these apparent spelling errors are more of an issue of chronology. Spelling and standards varied over time, so the given writing of a word during the Old Kingdom might be considerably different during the New Kingdom. Furthermore, the Egyptians were perfectly content to include older orthography ("historical spelling") alongside newer practices, as if it were acceptable in English to use the spelling of a given word from 1600 in a text written today. Most often ancient spelling errors are more of an issue of modern misunderstandings of the specific context of a given text.

Simple examples

| |||||||||||||||

| Ptolemy in hieroglyphs | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Era: Old Kingdom (2686–2181 BC) | |||||||||||||||

The glyphs in this cartouche are transliterated as:

| p t |

o | l m |

i i s | Ptolmiis |

though ii is considered a single letter and transliterated i or y.

Another way in which hieroglyphs work is illustrated by the two Egyptian words pronounced pr (usually vocalised as per). One word is 'house', and its hieroglyphic representation is straightforward:

| |

Here the 'house' hieroglyph works as an logogram: it represents the word with a single sign. The vertical stroke below the hieroglyph is a common way of indicating that a glyph is working as a logogram.

Another word pr is the verb 'to go out, leave'. When this word is written, the 'house' hieroglyph is used as a phonetic symbol:

| |

Here the 'house' glyph stands for the consonants pr. The 'mouth' glyph below it is a phonetic complement: it is read as r, reinforcing the phonetic reading of pr. The third hieroglyph is a determinative: it is an ideogram for verbs of motion that gives the reader an idea of the meaning of the word.

See also

- Writing in Ancient Egypt

- Egyptian language

- Other scripts

Notes and references

Bibliography

- Gardiner, Sir Alan H. (1973). Egyptian Grammar. The Griffith Institute. ISBN 0-900416-35-1.

- Allen, James P. (1999). Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521774837.

- Collier, Mark & Bill Manley (1998). How to read Egyptian hieroglyphs: a step-by-step guide to teach yourself. British Museum Press. ISBN 0-7141-1910-5.

- Faulkner, Raymond O. (1962). Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian. The Griffith Institute. ISBN 0-900416-32-7.

- Kamrin, Janice (2004). Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs; A Practical Guide. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 0-8109-4961-X.

- McDonald, Angela. Write Your Own Egyptian Hieroglyphs. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007 (paperback, ISBN 0520252357).

External links

- Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphics - Aldokkan

- Glyphs and Grammars Resources for those interested in learning hieroglyphs, compiled by Aayko Eyma.

- Hieroglyphs! Annotated directory of popular and scholarly resources.

- Egyptian Hieroglyphic Dictionary by Jim Loy

- Comprehensive Dictionary of Cartouches for all Egyptian Pharaohs

- Hieroglyphic fonts by P22 type foundry

- GreatScott.com's Hieroglyphs Commercial (free intro)

- Online course in Middle Egyptian hieroglyphs

- Ancient Egypt Online: Sign list, tutorials and quizzesA complete sign list, plus tutorials and quizzes