Cambodian campaign

| Cambodian Incursion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Vietnam Conflict | |||||||

| File:CamCit2.jpg The objective: U.S 1st Air Cavalry soldier displays communist recoiless rifle ammunition captured in Cambodia | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Lu Lan (ARVN, II Corps), Do Cao Tri (ARVN, III Corps), Nguyen Viet Thanh (ARVN, IV Corps), Creighton W. Abrams (U.S.) |

Pham Hung (political), Hoang Van Thai (military) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

58,608 (RVN), 50,659 (U.S.) | ~40,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

RVN: 809 killed in action, 3,486 wounded in action, United States: 434 killed in action, 2,233 wounded in action, 13 missing |

12,354 killed in action, 1,177 captured[1] | ||||||

The Cambodian Incursion was a military campaign conducted in eastern Cambodia during the late spring and summer of 1970 by the armed forces of the United States (U.S.) and the Republic of Vietnam (RVN or South Vietnam) during the Vietnam Conflict. A total of 13 major operations were conducted by the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) between 29 April and 22 July and by U.S. forces between 1 May and 30 June.

The objectives of the operations was the defeat of the approximately 40,000 troops of the People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) and the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (NLF) that were ensconced in the eastern border regions of Cambodia. As great a prize as the defeat of these forces would have been, the possibility of the occupation and destruction of large communist Base Areas and sanctuaries, which had been protected by Cambodian "neutrality" since their establishment in 1966, would have been just as satisfying. As far as the U.S. was concerned, such a course of action would provide a shield behind which the policy of Vietnamization and the withdrawal of U.S. forces from South Vietnam could proceed unmolested.

A change in the Cambodian government allowed a window of opportunity for the destruction of the Base Areas in 1970 when Prince Norodom Sihanouk was deposed and replaced by pro-American General Lon Nol. Allied military operations failed to eliminate many communist troops or to capture their elusive headquarters, known as COSVN, but the haul of captured logistical materiel in Cambodia prompted claims of success and victory which remain controversial to this day.

Preliminaries

Background

The People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) and NLF forces had been utilizing large sections of relatively unpopulated eastern Cambodia as sanctuaries into which they could withdraw from South Vietnam to avoid destruction and to rest and rehabilitate units without being attacked by allied forces. These Base Areas were also utilized by the communists to store weapons and materiel that had been transported on a large scale to the region on the so-called Sihanouk Trail. PAVN forces had begun moving through Cambodian territory as early as 1963. In 1966, Prince Norodom Sihanouk, ruler of Cambodia, convinced of eventual communist victory in Southeast Asia and fearful for the future of his nation, had concluded an agreement with the People's Republic of China which allowed the establishment of permanent PAVN/NLF bases on Cambodian soil and the use of the Cambodian port of Sihanoukville for resupply.[2]

During 1968, the indigenous communist movement labelled Khmer Rouge (Red Khmers) by Sihanouk, began an insurgency to overthrow the government. While they received very limited material help from the DRV at the time (the Hanoi government had no incentive to overthrow Sihanouk, since it was satisfied with his continued "neutrality"), they were able to shelter their forces in areas controlled by PAVN/NLF troops.

The U.S. government was fully cognizant of these activities in Cambodia, but refrained from taking overt military action against that nation in hopes of convincing the mercurial Sihanouk to alter his neutralist position. To accomplish this, President Lyndon B. Johnson authorized covert cross-border reconnaissance operations conducted by the highly-classified Studies and Observations Group in order to gather intelligence on PAVN/NLF activities in the border regions (Project Vesuvius) that would be presented to the prince in an effort to change his mind.

Menu and coup

The new commander of the U.S Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), General Creighton W. Abrams, recommended to President Richard M. Nixon shortly after his inauguration that the Cambodian Base Areas be attacked by aerial bombardment using B-52 Stratofortress bombers. The breaking point came with the launching of the PAVN "Mini-Tet" Offensive of 1969. Nixon, angered at what he perceived as a violation of the "agreement" with Hanoi after the cessation of the bombing of the DRV, authorized the covert air campaign. The first mission was dispatched on 18 March and, by the time it was completed 14 months later, more than 3,000 sorties been flown and 108,000 tons of ordnance had been dropped on eastern Cambodia.[3]

While Sihanouk was abroad in France for a rest cure in January 1970, government sponsored anti-Vietnamese demonstrations erupted throughout Cambodia.[4] Continued unrest spurred Prime Minister/Defense Minister Lon Nol to close the port of Sihanoukville to communist supplies and to issue an ultimatum on 12 March to the North Vietnamese to withdraw their forces from Cambodia within 72 hours. The prince, outraged that his "modus vivendi" with the communists had been disturbed, immediately arranged for a trip to Moscow and Beijing in an attempt to gain their agreement to apply pressure to the DRV to restrain its forces in Cambodia.

Lon Nol saw Cambodia's population of 400,000 ethnic Vietnamese as possible hostages to prevent PAVN attacks and ordered their roundup and internment. Cambodian soldiers and civilians then unleashed a reign of terror, murdering Vietnamese wherever they found them. On 15 April for example, 800 Vietnamese men had been rounded up at the village of Churi Changwar, tied together, executed, and their bodies dumped into the Mekong River.[5] They then floated downstream into South Vietnam. Cambodia's actions were denounced by both the North and South Vietnamese governments.

On 18 March, the Cambodian National Assembly deposed Sihanouk and named Lon Nol as provisional head of state. This led Sihanouk to immediately establish a government in exile in Beijing and to ally himself with the DRV, the Khmer Rouge, the NLF, and the Laotian Pathet Lao.[6] Sihanouk lent his name and his popularity in rural areas of Cambodia to a movement over which he had little control. The North Vietnamese then began directly supplying large amounts of weapons and advisors to the Khmer Rouge, and the country plunged into civil war.

When the supply conduit of Sihanoukville was shut down, PAVN began expanding its logistical system from southeastern Laos (the Ho Chi Minh Trail) into northeastern Cambodia. PAVN also launched an offensive (Campaign X) against the Cambodian army, quickly seizing large portions of the eastern and northeastern parts of the country, isolating and besieging or overrunning a number of Cambodian cities including Kampong Cham. Communist forces then approached within 20 miles og the capital, spurring President Nixon into action.

Planning

In response to events in Cambodia, President Nixon believed that there were distinct possibilities for U.S. action in Cambodia. Now that Sihanouk was gone, conditions were ripe for strong measures against the Base Areas. He was adament that some action be taken to support "The only government in Cambodia in the last twenty-five years that had the guts to take a pro-Western stand."[7] The president solicited proposals for actions from the Joint Chiefs of Staff and MACV, who presented him with a series of options: a a naval quarantine the Cambodian coast; the launching of South Vietnamese and American airstrikes; the expansion of hot pursuit across the border by ARVN forces; or a ground invasion by ARVN, U.S. forces, or both.[8]

Not all of the members of the administration agreed that an invasion of Cambodia was either militarily or politically expedient. Secretary of Defense Melvin R. Laird and Secretary of State William P. Rogers were both opposed to any such operation (as they had the Menu bombings) due to their belief that it would engender intense domestic opposition. Both were scorned by Kissinger for their "bureaucratic foot-dragging."[9] As a result, Laird was bypassed by the Joint Chiefs in advising the White House on planning and preparations for the Cambodian operation.[10]

During a televised address on 20 April, Nixon announced the withdrawal of 150,000 U.S. troops from South Vietnam during the year. This planned withdrawal tended to place restrictions on any U.S. action in Southeast Asia. By the spring of 1970, MACV still maintained 330,648 U.S. Army and 55,039 Marine Corps troops in South Vietnam, most of whom were concentrated in 81 infantry and tank battalions.[11] However, many of them were preparing to leave the country or expected to leave in the near future and would not be available for immediate combat operations.

On 22 April Nixon authorized the planning of a South Vietnamese invasion of the "Parrot's Beak," believing that "Giving the South Vietnamese an operation of their own would be a major boost to their morale as well as provide a practical demonstration of the success of Vietnamization."[12] On the following day, Secretary Rogers, testified before the House Appropriations Subcommittee that "the administration had no intentions...to escalate the war. We recognize that if we escalate and get involved in Cambodia with our ground troops that our whole program [Vietnamization] is defeated."[13]

South Vietnamese forces had been rehearsing for just such an operation since late March. On the 27th, an ARVN Ranger Battalion had advanced into Kandal Province to destroy a communist base. Four days later, ARVN troops drove 16 kilometers into Cambodia. Lon Nol, who had attempted to follow a neutralist policy of his own, finally requested military assistance from the U.S. government on April 14. On that same day, ARVN conducted the first of three brief cross-border operations under the aegis of Operation Toan Thang (Complete Victory) 41, sending armored cavalry units into regions of Cambodia's Svay Rieng Province nicknamed the "Angel's Wing" and the "Crow's Nest" (from their perceived shapes on maps). On 20 April 2,000 South Vietnamese troops advanced into the "Parrot's Beak", killing 144 PAVN troops.[14] On the 22nd, Nixon authorized American air support for the South Vietnamese operations. All of these incursions into Cambodian territory were simply reconnaissance missions in preparation for a more wide-scale incursion that was being planned by MACV and its ARVN counterparts, subject to authorization by Nixon.

Nixon then authorized General Abrams to begin planning for an operation into the Fishhook region.[15] Abrams handed the planning off to General Michael Davison, commander of the II Field Force. 72 hours later, the plan was submitted to the White House. Kissinger asked his aide, Larry Lynn, to review the plan on 26 April, and the NSC staffer was appalled by its "sloppiness". The problem was the pressure of time and the desire of the president for secrecy. The Cambodian monsoon was only two months away. The Cambodian desk at the U.S. embassy in Saigon was not notified of the invasion plan, nor were the Phnom Penh embassy or Lon Nol. The Cambodian leader consistently opposed all foreign incursions and wanted only money and arms from the U.S.

On the evening of April 26 Nixon finally decided "We would go for broke" and gave his authorization.[16] The joint U.S./ARVN incursion would begin on 1 May with the stated goals of the campaign being: reducing allied casualties in South Vietnam; assuring the continued withdrawal of U.S. forces from Vietnam; and enhancing the U.S./Saigon government position at the peace negotiations being conducted in Paris.

General Abrams had suggested that the incursion be routinely announced from Saigon. At 21:00 on 30 April, however, President Nixon appeared on all three television networks to announce that "It is not our power but our will and character that is being tested tonight" and that "the time has come for action." He announced his decision to launch American forces into Cambodia with the spacial objective of capturing "the headquarters of the entire communist military operation in South Vietnam."

Operations

Parrot's Beak and Fishook

South Vietnamese forces had begun their incursion on 30 April 1970 with Operation Toan Thang 42, in which 12 ARVN battalions of approximately 8,700 troops (two armoured cavalry squadrons from III Corps and two from the 25th and 5th Infantry Divisions, an infantry regiment from the 25th Infantry Division, and four Ranger battalions from the 2nd Ranger Group) crossed into the Parrot's Beak region of Kompong Cham Province under the command of Lieutenant General Do Cao Tri, the commander of III Corps, who had a reputation as one of the most aggressive and competent ARVN generals.[17] During their first two days in Cambodia, ARVN units had several sharp encounters with North Vietnamese troops. The communists had seen the incursion coming and were conducting delaying actions in order to allow the bulk of their forces to escape to the west. The ARVN operation soon became a search and destroy mission, with South Vietnamese troops combing the countryside in small patrols looking for PAVN supply caches.

Phase II of the operation saw the arrival of elements of the U.S. Ninth Infantry Division. Four tank-infantry task forces attacked into the "Parrots Beak" from the south. After three days of operations, 1,010 PAVN troops had been killed and 204 prisoners taken for the loss of 66 ARVN dead and 330 wounded.[18] During these operations the South Vietnamese Air Force flew more than 1,600 sorties supported by 310 USAF missions.[19]

On 1 May an even larger operation, known by the ARVN as Operation Toan Thang 43 and by MACV as Operation Rockcrusher, got underway as 36 B-52s dropped 774 tons of bombs along the southern edge of the "Fishhook". This was followed by an hour of massed artillery fire and another hour of strikes by tactical fighter bombers. At 10:00, the 1st Air Cavalry Division and the 11th Armoured Cavalry Regiment and six ARVN battalions (the 1st ARVN Armoured Cavalry Reginment and the 3rd ARVN Airborne Brigade) then entered Svay Rieng Province of Cambodia. Known as Task Force Shoemaker after the local U.S. commander, the force attacked the long-time communist stronghold with 10,000 U.S. and 5,000 South Vietnamese troops. The operation utilized mechanized infantry and armored units to drive deep into the province where they would link up with ARVN airborne and U.S. airmobile units that had been lifted in by helicopter.

Opposition to the incursion was expected to be heavy, but PAVN/NLF forces had begun moving westward two days before the advance began. By 3 May, MACV had reported only eight Americans killed and 32 wounded, low casualties for such a large operation.[20] There was only scattered and sporadic contact with delaying forces such as that experienced by elements of the U.S. 11th Armoured Cavalry three kilometers inside Cambodia. PAVN troops opened fire with small arms and rockets only to be blasted by tank fire and tactical airstrikes. When the smoke had cleared, 50 dead PAVN soldiers were counted on the battlefield.[21]

The North Vietnamese had ample forewarning of the impending attack. A 17 March directive from the headquarters of the B-3 Front that was captured during the incursion, ordered PAVN/NLF forces to "break away and avoid shooting back...Our purpose is to conserve forces as much as we can".[22] The only surprised party amongst the participants in the incursion seemed to be Lon Nol, who had been informed by neither Washington nor Saigon concerning the impending invasion of his country. He only discovered the fact after a telephone conversation with the head of the U.S. mission, who had found out about it himself only from a radio broadcast.[23]

The only conventional battle fought by American troops occurred on 1 May at the town of Snoul, the suspected terminus of the Sihanouk Trail at the junction of Routes 7, 13, and 131. Elements of the U.S. 11th Armored Cavalry and supporting helicopters came under PAVN fire while approaching the town and its airfield. When a massed American attack was met by heavy resistance, the Americans backed off, called in air support and blasted the town for two days, reducing it to rubble. During the action, Brigadier General Don Starry, commander of the 11th Armored Cavalry, was wounded by grenade fragments and medevaced.

On the following day, elements of the U.S. 1st Air Cavalry division entered what came to be called "The City", southwest of Snoul. The two-square mile PAVN complex contained over 400 thatched huts, storage sheds, and bunkers, each of which was packed with food, weapons, and ammunition. There were truck repair facilities, hospitals, a lumber yard, 18 mess halls, a pig farm, and even a swimming pool.

Forty kilometers to the northeast, other Air Cavalry elements discovered a larger base on 6 May. Nicknamed "Rock Island East" after the U.S. Army's Rock Island Arsenal in Illinois, the area contained more than 6.5 million rounds of antiaircraft ammunition, 500,000 rifle rounds, thousands of rockets, several General Motors trucks, and several telephone switchboards.[24]

Due to increasing political and domestic turbulence in the U.S., President Nixon issued a directive on 7 May limiting the distance and duration of the U.S. operations in Cambodia to a depth of 30 kilometers (21.7 miles) and setting a deadline of 30 June for the withdrawal of all U.S. forces to South Vietnam.

While on patrol 20 kilometers northeast of "Rock Island East" on 23 May, a point man nicknamed Shaky from the Fifth Battalion, Seventh Cavalry, tripped over a metal plate buried just below the surface of the ground. The trooper was later killed by PAVN defenders, but the cache he had uncovered was the first of 59 buried storage bunkers at the site what was thereafter known as "Shakey's Hill." The bunkers contained thousands of cases of weapons and ammunition, which were turned over to the Cambodian army.

The one thing that was not found was COSVN. On 1 May a tape of Nixon's announcement of the incursion was played for General Abrams, "who must have cringed" when he heard the president state that the capture of the headquarters capture was one of the major objectives of the operation.[25] MACV intelligence knew that the mobile and widely- dispersed headquarters would be difficult to locate. In response to a White House query before the fact, MACV had replied that "major COSVN elements are dispersed over approximately 110 square kilometers of jungle" and that "the feasibility of capturing major elements appears remote".[26]

Supporting operations

During the first week of operations, additional battalion and brigade units were committed to the operation, so that between 6 and 24 May, a total of 90,000 allied troops (including 33 U.S. maneuver battalions) were conducting operations inside Cambodia. South Vietnamese forces were not constrained by the time and geographic limitations placed upon U.S. units. From the provincial capital of Svay Rieng ARVN elements pressed westward to Kampong Trabec, where on 14 May their 8th and 15th Armored Cavalry regiments defeated the 88th PAVN Infantry Regiment. On 23 May, the South Vietnamese pushed beyond the deepest U.S. penetrations and attacked the town of Krek.

In the II Corps area Operation Binh Tay I (Operation Tame the West) was launched by the 1st and 2nd Brigades of the U.S. 4th Infantry Division and the 40th ARVN Infantry Regiment against Base Area 702 (the traditional headquarters of the communist B-2 Front) in northeastern Cambodia from 5 May - 25 May. Assaulting via helicopter, initial American forces were driven back by antiaircraft fire. After airstrikes, the 3rd Battalion, 506th Infantry, landed without opposition. Its sister unit, the 1st Battalion, 14th Infantry was driven off by similar fire and did not return until the 6th. The 3rd Battalion, 8th Infantry inserted only 60 men before enemy fire (which shot doen one helicopter and damaged two others) shut down the landing zone, leaving them stranded overnight.

The rest of the battalion lnaded without opposition the next day. On the 7th, the divisions 2nd Brigade inserted its three battalions unopposed. After ten days (and only one significant firefight) the American troops left, leaving the area to the ARVN. Historian Shelby Stanton has noted that "there was a noted lack of aggressiveness" in the combat assault and that the division seemed to be "suffering from almost total combat paralysis."[27] During Operation Binh Tay II, the 22nd ARVN Division moved against Base Area 702 from 14 May - 26 May. Operation Binh Tay II Phase II was carried out by ARVN forces against Base Area 701. From 20 May till 27 June the ARVN 22nd Division conducted operations against Base Area 740.

In the III Corps Tactical Zone, Operation Toan Thang 44 (Operation Bold Lancer), an operation conducted by the 1st and 2nd Brigades of the U.S 25th Infantry Division and the 3rd Brigade of the U.S. 9th Infantry Division crossed over the border 48 kilometers southwest of the Fishhook into an area known as the "Dog's Head" from 6 May - 30 June. The 3rd Brigade, of the 1st Air Cavalry Division also expanded operations in "the Belly" area north of An Loc in Phuoc Long Province from 6 May till 25 June.

It was already too late for thousands of ethnic Vietnamese murdered by Cambodia persecution, but there were tens of thousands of Vietnamese still in Cambodia that could now be evacuated to safety. South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu arranged with Lon Nol to repatriate as many as were willing to leave (this did not prevent the Cambodian government from stripping them of their homes and other personal property). He then launched Operation Cuu Long, in which ARVN ground forces, including mechanized and armoured units, drove west and northwest up the eastern side of the Mekong River from 9 May - 1 July. A combined force of 110 Vietnamese Navy and 30 U.S. vessels proceeded up the Mekong to Prey Veng, permitting IV Corps ground forces to move westward to Phnom Penh and to aid ethnic Vietnamese seeking flight to South Vietnam. Those who did not wish to be repatriated were forcibly expelled.[28] Surprisingly, North Vietnamese forces did not oppose the evacuation, though they could easily have done so.

Other operations conducted from IV Corps included Operation Cuu Long II (16 May - 24 May), which continued actions along the western side of the Mekong River. Lon Nol had requested that the ARVN help in the retaking of Kompong Speu (previously known as Sihanoukville), along Route 4 southwest of Phnom Penh and 90 miles inside Cambodia. A 4,000-man ARVN armoured task force linked up with Cambodian ground troops and retook the town. Operation Cuu Long III (24 May - 30 June) was an evolution of the previous operations after U.S. forces left Cambodia.

After rescuing Vietnamese from the Cambodians, ARVN was tasked with relieving the city of Kompong Cham, 70 kilometers northwest of the capital and the site of Cambodian Military Region I's headquarters. On 23 May, General Tri led a column of 10,000 ARVN troops along Route 7 to the 180-acre Chup rubber plantation, where PAVN resistance was expected to be heavy. Surprisingly. there was no battle and the siege of Kompong Cham was lifted at a cost of 98 PAVN troops killed.[29]

Aerial operations for the incursion got off to a slow start. Reconnaissance flights over the operational area were restricted since MACV believed that they might serve as a signal of intention. The role of the Air Force in the planning for the incursion itself was minimal at best, in part to preserve the secrecy of Menu which was then considered an overture to the thrust across the border.[30]

On 17 April, General Abrams requested that the president approve Operation Patio, covert tactical airstrikes in support of Studies and Observations Group recon elements "across the fence" in Cambodia. This authorization was given, allowing U.S. aircraft to penetrate 13 miles into northeastern Cambodia. This boundary was extended to 29 miles along the entire frontier on 25 April. Patio was terminated on 18 May after 156 sorties had been flown.[31] The last Menu mission was flown on 26 May.

During the incursion U.S. and ARVN ground units were supported by 6,000 aerial sorties or 210 per day. During operations in the "Fishook," for example, the USAF flew 3,047 sorties and the South Vietnamese Air Force 332.[32] These tactical airstrikes were supplemented by 186 B-52 missions in the border regions.[33] Coinciding with the incursion was the inauguration of Operation Freedom Deal, aerial interdiction strikes conducted in Cambodia. These missions were limited to a depth of 48-kilometers between the RVN border and the Mekong River.

Within two months, however, the limit of the operational area was extended past the Mekong, and U.S. tactical aircraft were soon directly supporting Cambodian forces in the field. These missions were officially denied by the U.S. and false coordinates were given in official reports to hide their existence. Defense Department records indicated that out of more than 8,000 combat sorties flown in Cambodia between July 1970 and February 1971, approximately 40 percent were flown outside the authorized Freedom Deal boundary.[34]

Repercussions

The North Vietnamese response to the incursion was to avoid contact with the offensive if possible and to fall back westward and regroup. PAVN forces were well aware of the planned attack and many COSVN/B-3 Front military units were already far to the north and west conducting operations against the Cambodians when the offensive began.[35] In 1969 PAVN logistical units had already begun the largest expansion of the Ho Chi Minh Trail conducted during the entire conflict. As a response to the loss of their Cambodian supply route, North Vietnamese forces seized the Laotian towns of Attopeu and Saravane during the year, pushing what had been a 60 mile corridor to a width of 90 miles and opening the entire length of the Kong River system into Cambodia.[36] A new logistical command, the 470th Transportation Group, was created to handle logistics in Cambodia and the new "Liberation Route" ran through Siem Prang and reached the Mekong at Stung Treng.[37]

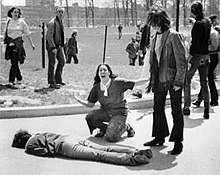

As foreseen by secretary Laird, fallout from the incursion was quick in coming on the campusus of America's universities, as protests erupted against what was perceived as an expansion of the conflict into yet another country. On 4 May the unrest led to violence when Ohio National Guardsmen shot and killed four unarmed students (two of whom were not protesters) during the Kent State shootings. On 8 May 100,000 protesters gathered in Washington while one day previously at the University of Buffalo police had wounded four more demonstrators. At Jackson State College in Mississippi, highway patrolmen shot and killed two black sutdent protesters. Nationwide, 30 ROTC buildings went up in flames or were bombed while 26 schools witnessed violent clashes between students and police.

Simultaneously, public opinion polls during the second week of May showed that 50 percent of the American public approved of President Nixon's actions.[38] 58 percent blamed the students for what had occurred at Kent State. On 20 May 100,000 construction workers, tradesmen, and office workers marched through New York City in support of the president's policies during a pro-war rally.

Reaction in the U.S. Congress to the incursion was swift. Senators Frank F. Church (D, ID) and John S. Cooper (R, KY), proposed an amendment to the Foreign Military Sales Act that would have cut off funding not only for U.S. ground operations and advisors in Cambodia, but would also have ended U.S. air support for Cambodian dforces. On 30 June the Senate passed the act with the amendment included. The bill was defeated in the House of Representatives. The newly-amended act did, however, rescind the Southeast Asia Resolution (better known as the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution) under which Presidents Johnson and Nixon had conducted military operations for seven years without a declaration of war.

The Cooper-Church Amendment was resurrected during the winter and incorporated into the Supplementary Foreign Assistance Act of 1970. This time the measure made it through both houses of Congress and became law on 22 December. As a result, all U.S. ground troops and advisors were barred from participating in military action in both Laos and Cambodia, while the air war that being conducted in both countries by the U.S. Air Force was ignored.

Conclusion

Richard Nixon proclaimed the incursion to be "the most successful military operation of the entire war."[39] General Abrams was of like mind, believing that time had been bought for the pacification of the South Vietnamese countryside and that U.S. and ARVN forces had been made safe from any attack out of Cambodia during 1971 and 1972. A "decent interval" had been obtained for the final American withdrawal. ARVN General Tran Dinh Tho was more skeptical: "despite its spectacular results...it must be recognized that the Cambodian incursion proved, in the long run, to pose little more than a temporary disruption of North Vietnam's march toward domination of all of Laos, Cambodia, and South Vietnam."[40]

John Shaw and other historians, military and civilian, have based the conclusions of their work on the incursion on the premise that the North Vietnamese logistical system in Cambodia had been so badly damaged that it was rendered ineffective. The next large-sacle PAVN offensive, the Nguyen Hue Offensive of 1972 (called the Easter Offensive in the West) would be launched out of the southern DRV and western Laos, not from Cambodia, proof positive that the Cambodian operations had succeeded. The fact that PAVN forces were otherwise occupied in Cambodia and had no such offensive plan (so far as is known) was seemingly irrelevant. The fact that logistically, a northern offensive (especially a conventional one backed by armour and heavy artillery) would be launched closer to its source of manpower and supply also seemed to be of little consequence.

The logistical haul discovered, removed, or destroyed in eastern Cambodia during the operations was indeed prodigious: 20,000 individual and 2,500 crew-served weapons; 7,000 to 8,000 tons of rice; 1,800 tons of ammunition (including 143,000 mortar shells, rockets, and recoiless rifle rounds); 29 tons of communications equipment; 431 vehicles; and 55 tons of medical supplies.[41] MACV intelligence estimated that PAVN/NLF forces in southern Vietnam required 1,222 tons of all supplies each month to keep up a normal pace of operations.[42] Due to the loss of its Cambodian supply system and continued aerial interdiction in Laos, MACV estimated that for every 2.5 tons of materiel sent south down the Ho Chi Minh Trail, only one ton reached its destination. Unfortunately, the true loss rate was probably only around ten percent.[43]

South Vietnamese forces had performed well during the incursion but their leadership was uneven. General Tri proved a resourceful and inspiring commander, earning the sobriquet the "Patton of the Parrot's Beak" from the American media. General Abrams also praised the skill of General Nguyen Viet Thanh, commander of IV Corps and planner of the Parrot's Beak operation.[44] Unfortunately, both officers were killed in helicopter crashes - Thanh on 2 May in Cambodia and Tri in February 1971. Other ARVN commanders, however, had not performed well. Even at this late date in the conflict, the appointment of ARVN general officers was prompted by political loyalty rather than professional competence. As a test of Vietnamization, the incursion was praised by American generals and politicians alike, but the Vietnamese had not really performed alone. The participation of U.S. ground and air forces had precluded any such claim. When called on to conduct solo offensive operations during the incursion into Laos (Operation Lam Son 719) in 1971, the ARVN's continued weaknesses would become all too apparent.

Perhaps those most dramatically effected by the results of the incursion (and whose fate was basically ignored by all but a few historians listed below) were the Cambodian people. The incursion, about which the Cambodian government was not even informed until it was under way, heated up what was basically a low-key civil war and irrevocably widened the boundaries of the Second Indochina War. The withdrawal of U.S. forces, after only a 30-day campaign, "left a void so great that neither the Cambodian nor the South Vietnamese armies were able to fill it."[45]

Lon Nol's forces then had to contend with not only PAVN and the NLF, but with an ever-growing indigenous insurgency, which was now fully supported by Hanoi and its armed forces. The Nixon administration, callous of the weakness of the Cambodian regime and its armed forces, pushed its new ally into a conflict that it had no possibility of winning.[46] Cambodia (like neighboring Laos) would be sacrificed for the withdrawal of the Americans and the future existence of the Republic of Vietnam.[47] Millions of Cambodians would pay the ultimate price as a result of those decisions.

References

Notes

- ^ Shaw, p. 158. His original source was the Current Historical Evaluation of Counterinsurgency Operations (Project CHECO).

- ^ Lipsman & Doyle, p. 127. Victory in Vietnam, p. 465, fn24.

- ^ Nalty, pgs. 127-133.

- ^ Wilfred Deac, Road to the Killing Fields. College Station TX: Texas A&M University, 1997, pgs. 56-57.

- ^ Deac, p. 75.

- ^ Lipsman & Doyle, p. 144.

- ^ Lipsman & Doyle, p. 147.

- ^ Lipsman & Doyle, p. 147.

- ^ Nalty, p. 83.

- ^ Sorely, p. 202.

- ^ Stanton, pgs. 319-320.

- ^ Lipsman & Lipsman, p. 149.

- ^ Lipsman & Doyle, p. 152.

- ^ Lipsman & Doyle, p. 149.

- ^ Planning for the incursion had actually begun in March, but was kept so tightly under wraps that Davison was not even informed agout it and went on to create what he believed was "his" plan. For security purposes, U.S. brigade commanders were informed only a week in advance while battalion commanders got only two or three days' notice. Shaw, pgs. 58-60.

- ^ Lipsman & Doyle, p. 152.

- ^ Tri's operation was to have begun on the 29th but the general refused to budge, claiming that his astrologer had told him "the heavens were not auspicious". Shaw, p. 53.

- ^ Shaw, p. 54.

- ^ Shaw, p. 56.

- ^ Lipsman & Doyle, p. 164.

- ^ Lipsman & Doyle, p. 164.

- ^ Sorely, p. 203.

- ^ Stanley Karnow, Vietnam. New York: Viking Books, 1983, p. 608.

- ^ Lipsman & Doyle, p. 167.

- ^ Sorely, p. 203.

- ^ Sorely, p. 203.

- ^ Shelby L. Stanton, The Rise and Fall of an American Army. New York: Dell, 1985, p. 324.

- ^ Lipsman & Doyle, p. 174.

- ^ Lipsman & Doyle, p. 177.

- ^ Schlight, pgs. 183-184.

- ^ Morocco, Operation Menu, p. 146.

- ^ Shaw, p. 75.

- ^ Morocco, Rain of Fire, p. 84.

- ^ Morocco, Operation Menu, p. 148.

- ^ Shaw, p. 45.

- ^ Prados, p. 191.

- ^ Victory in Vietnam, p. 382.

- ^ Lipsman & Doyle, p. 182.

- ^ Shaw, p. 153.

- ^ Tho, p. 182.

- ^ Shaw, p. 162.

- ^ Shaw, p. 163.

- ^ Due to lack of verifiable sources in the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, this figure is, at best, an estimate. The official Vietnamese figure of losses in transported supplies in 1970 was 3.4 percent. Victory in Vietnam, p. 261. The U.S. Air Force's best estimate for the same time period was that one-third was destroyed in transit. Nalty, War On Trucks, p. 297.

- ^ Sorely, p. 221.

- ^ Sutsakhan, Lt. Gen. Sak Khmer Republic at War. Washington DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1984, p. 174.

- ^ Shawcross, p. 169.

- ^ Lamy, p. 47.

Sources

Published government documents

- Military Institute of Vietnam, Victory in Vietnam: The Official History of the People's Army of Vietnam, 1954-1975. Lawrence KS: University of Kansas Press, 2002.

- Lamy, Colonel Perry L. Barrel Roll, 1968-1973: Am Air Campaign in Support of National Policy. Maxwell Air Force Base AL: Air University Press, 1995.

- Nalty, Bernard C. Air War Over South Vietnam: 1968-1975. Washington DC: Air Force History and Museums Program, 2000.

- Nalty, Bernard C. War Against Trucks: Aerial Interdiction in Southern Laos, 1968-1972. Washington DC: Air Force History and Museums Program, 2005.

- Sutsakhan, Lieutenant General Sak, The Khmer Republic at War and the Final Collapse. Washington DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1984.

- Tho, Brigadier General Tran Dinh, The Cambodian Incursion. Washington DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1979.

Secondary accounts

- Deac, Wilfred, Road to the Killing Fields: The Cambodian Civil War of 1970-1975. College Station TX: Texas A&M University, 1997.

- Karnow, Stanley, Vietnam: A History. New York: Viking Books, 1983.

- Lipsman, Samuel, Edward Doyle, et al. Fighting for Time: 1969-1970. Boston: Boston Publishing Company, 1983.

- Morocco, John, Operation Menu in War in the Shadows. Boston: Boston Publishing Company, 1988.

- Morocco, John, Rain of Fire': Air War, 1969-1973 Boston: Boston Publishing Company, 1985.

- Nolan, Keith, Into Cambodia: Spring Campaign, Summer Offensive, 1970. Novato CA: Presidio Press, 1990.

- Palmer, Dave Richard, Summons of the Trumpet: A History of the Vietnam War from A Military Man's Point of View. Novato CA: Presidio Press, 1978.

- Prados, John, The Blood Road: The Ho Chi Minh Trail and the Vietnanm War. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1998.

- Shaw, John M. The Cambodian Campaign: The 1970 Offensive and America's Vietnam War. Lawrence KS: University of Kansas Press, 2005.

- Shawcross, William, Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon and the Destruction of Cambodia. New York: Washington Square Books, 1979.

- Sorley, Lewis, A Better War: The Unexamined Victories and Final Tragedy of America's Last Years in Vietnam. New York: Harvest Books, 1999.

- Stanton, Shelby L. The Rise and Fall of An American Army: U.S. Ground Forces in Vietnam, 1965-1973. New York: Dell Books, 1985.

External sites

- Bombs over Cambodia-Ben Kiernan and Taylor Owen

- The Cambodian Incursion: A Hard Line for Change by Major Jeremiah S. Boenisch