Pub

This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. |

A public house, usually known as a pub, is an establishment which serves alcoholic drinks and beer for consumption on the premises, usually in a homely setting. Pubs are commonly found in English-speaking countries, particularly in the United Kingdom, Ireland, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

In North America, drinking establishments with a British or Irish name or theme are called pubs as well; the appellation "pub" itself is often a component of this theme. Although the terms may have different connotations, there is no definitive difference between pubs, bars, taverns and lounges where alcohol is served commercially.

Traditionally, a pub which offers lodging may be called an inn or (more recently) hotel in the UK. Today many pubs, in the UK and Australia in particular, with the word "inn" or "hotel" in their name no longer offer accommodation, or in some cases have never done so. Some pubs often bear the name of "hotel" because they are in countries where stringent anti-drinking laws were once in place. In Scotland, only hotels could serve alcohol on Sundays; in Australia, this restriction operated all through the week.

Overview of British pubs

In the 1930s the Anglo-French writer Hilaire Belloc penned the following cautionary warning:

When you have lost your inns, drown your empty selves, for you will have lost the last of England!

Public houses are culturally and socially different from places such as cafés, bars, bierkellers and brewpubs. There are approximately 60,000 public houses in the United Kingdom, with one in almost every village. In many places, especially in villages, a pub can be the focal point of the community, playing a similar role to the local church in this respect.

Pubs are social places based on the sale and consumption of alcoholic beverages, and most public houses offer a range of beers, wines, spirits, alcopops and soft drinks. Many pubs are controlled by breweries, so beer is often better value than wines and spirits, whilst soft drinks can be almost as expensive. Beer served in a pub may be cask ale ("real ale" or cask-conditioned ale in the UK) traditionally brewed, matured in the pub, and served at cool cellar temperature from a hand-pump - or keg beer made in industrial quantities, pasteurised, pressurised, and chilled. The beer lends most pubs a pleasant, memorable aroma. All pubs also have a range of non-alcoholic beverages available. Traditionally the windows of town pubs are of smoked or frosted glass so that the clientele are obscured from the street. In the last twenty years in the UK and other countries there has been a move away from frosted glass towards clear glass, a trend which fits in with brighter interior decors.

The owner, tenant or manager (licensee) of a public house is known as the publican or landlord. Each pub generally has a crowd of regulars, people who drink there regularly. The pub that people visit most often is called their local. In many cases, this will be the pub nearest to their home, but some people choose their local for other reasons: proximity to work, a traditional venue for their friends, the availability of a particular cask ale, non-smoking or smoking provision, or maybe a darts team or pool table.

A society with a particular interest in the traditional British beers and the preservation of the 'integrity' of the public house is the Campaign for Real Ale, (CAMRA).

Colloquialisms for the public house include boozer, battle cruiser, the local, watering hole, or (in episodes of Minder and the pages of Viz) nuclear sub, rub-a-dub-dub, golf club (see Cockney rhyming slang).

History

The inhabitants of the British Isles have been drinking ale since the Bronze Age, but it was with the arrival of the Romans and the establishment of the Roman road network that the first inns, in which the weary traveller could obtain refreshment, began to appear. By the time the Romans left, the beginnings of the modern pub had been established. They became so commonplace that in 965 King Edgar decreed that there should be no more than one alehouse per village.

The Royal Standard of England, a pub near Beaconsfield, is a present-day survivor that grew from a Saxon alehouse. [1] The Saxon alewife would put a green bush up on a pole to let people know her brew was ready. As well as strong ale, small ale was made to drink instead of water, which was rightly regarded as dirty and unsafe.[1]

A traveller in the early Middle Ages could obtain overnight accommodation in monasteries, but later a demand for hostelries grew with the popularity of pilgrimages and travel. The Hostellers of London were granted guild status in 1446 and in 1514 the guild became the Worshipful Company of Innholders.

Traditional English ale was made solely from fermented malt. The practice of adding hops to produce beer was introduced from the Netherlands in the early 15th century. Alehouses would each brew their own distinctive ale, but independent breweries began to appear in the late 17th century. By the end of the century almost all beer was brewed by commercial breweries.

The 18th century saw a huge growth in the number of drinking establishments, primarily due to the introduction of gin. Gin was brought to England by the Dutch after the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and started to become very popular after the government created a market for grain that was unfit to be used in brewing by allowing unlicensed gin production, whilst imposing a heavy duty on all imported spirits. As thousands of gin-shops sprang up all over England, brewers fought back by increasing the number of alehouses. By 1740 the production of gin had increased to six times that of beer and because of its cheapness it became popular with the poor leading to the so-called Gin Craze. Over half of the 15,000 drinking establishments in London were gin-shops. Beer maintained a healthy reputation as it was usually safer to drink ale than water, but the drunkenness and resultant lawlessness created by gin was seen to lead to ruination and degradation of the working classes. The distinction was illustrated by William Hogarth in his engravings Beer Street and Gin Lane. The Gin Act (1736) imposed high taxes on retailers but led to riots in the streets. The prohibitive duty was gradually reduced and finally abolished in 1742. The 1751 Gin Act however was more successful. It forced distillers to sell only to licensed retailers and brought gin-shops under the jurisdiction of local magistrates.

Licensing and records

The Wine and Beerhouse Act 1869 re-introduced the stricter controls of the previous century. The sale of Beers, Wines or Spirits required a valuable license for the premises from the local magistrates. A series of further provisions specifically regulated gaming, drunkenness, prostitution and other undesirable conduct on licenced premises, enforceable by prosecution or more effectively by the landlord under threat of forfeiting his licence. Licences were only granted, transferred or renewed at special Licensing Sessions courts, and were strictly limited to respectable individuals (initially often ex-servicemen or police). Licence conditions varied widely, according to local practice. They would specify permitted hours, which might require Sunday closing, or conversely permit all-night opening near a market. Typically they might require opening throughout the permitted hours, and the provision of food or lavatories. Once obtained, licences were jealously protected by the licensees (always individuals expected to be generally present, not a remote owner or company), and even "Occasional Licences" to serve drinks at temporary premises such as fêtes would usually be granted only to existing licensees. Objections might be made by the police, rival landlords or anyone else on the grounds of infractions such as serving drunks, disorderly or dirty premises, or ignoring permitted hours. However licensing was gradually liberalised after the 1960s, until contested licensing applications became very rare, and the remaining administrative function was transferred to Local Authorities in 2005.

Detailed records were kept on licensing, giving the Public House, its address, owner, licensee and misdemeanours of the licensees for periods often going back for hundreds of years. Many of these records survive and can be viewed, for example, at the London Metropolitan Archives centre.

By the end of the 18th century a new room in the pub was established: the saloon. Beer establishments had always provided entertainment of some sort—singing, gaming or a sport. Balls Pond Road in Islington was named after an establishment run by Mr Ball that had a pond at the rear filled with ducks, where drinkers could, for a certain fee, go out and take their chance at shooting the fowl. More common, however, was a card room or a billiards room. The saloon was a room where for an admission fee or a higher price at the bar, singing, dancing, drama or comedy was performed. From this came the popular music hall form of entertainment—a show consisting of a variety of acts. A most famous London saloon was the Grecian Saloon in The Eagle, City Road, which is still famous these days because of an English nursery rhyme: "Up and down the City Road / In and out The Eagle / That's the way the money goes / Pop goes the weasel.". The implication being that, having frequented The Eagle public house, the customer spent all his money, and thus needed to 'pawn' his 'weasel' to get some more. The exact definition of the 'weasel' is unclear but the two most likely definitions are: that a weasel is a flat iron used for finishing clothing; or that 'weasel' is cockney rhyming slang for a coat (weasel and stoat).

A few pubs have stage performances, such as serious drama, stand-up comedians, a musical band or striptease; the highly contentious juke box or "muzak" has otherwise replaced the musical tradition of a piano and singing.

By the 20th century, the saloon had settled into a middle class room—carpets on the floor, cushions on the seats, and a penny or two on the prices, while the public bar had remained working class—bare boards, sometimes with sawdust to absorb the spitting, hard seats, and cheap beer. The public bars gradually improved until sometimes almost the only difference was in the prices, so that customers could choose between economy and exclusivity (or youth and age, or a jukebox or dartboard). During the blurring of the class divisions in the 1960s and 70s, the distinction between the saloon and the public bar was seen as archaic, and was abolished, usually by the removal of the dividing wall or partition itself. While the names of Saloon and Public Bar may still be seen on the doors of pubs, once inside the prices and the standard of decoration are the same throughout the premises, and it often comprises one large room. However, the issues of smoking and eating encourage some pubs to maintain distinct rooms or areas, especially where the building requires it, and in a few pubs there still remain rooms or seats which by local custom "belong" to particular customers.

The Private Bar and the Bottle & Jug

The “Private Bar” The entrance to which was not exactly hidden, but “round the side” almost out of sight from the two main bars “The “Saloon Bar” and the “Public Bar” entrances. These small rooms were normally with a bar wide enough to accommodate two people standing side by side, Two tables with two chairs at each. You could easily hear the noise from the public bar (loud and manly) And from the saloon bar (A buzz mixture of male and female) Mostly ladies frequented these small “Private” bars, and mostly middle aged, divorced, lonely, or widowed, hardly ever on their own and never “ladies of the night” though. The other bar was the “Bottle and Jug” which pretty much describes itself. Today's equivalent of an “Off Licence” perhaps also describes it. The main difference is the size. It consisted of a room where four people could stand shoulder to shoulder, a bar wet with spilt beer. You could purchase a bottle of beer or two and if desired you brought your own “Jug” had it filled with draft beer by the landlady, paid and left presumably spilling some on the bar, and the floor. No consumption of beer and no loitering in this part of the pub. Children although illegal in pubs were picking up dad’s jug of beer for the evening.

UK Opening hours and regulation

From the middle of the 19th century restrictions were placed on the opening hours of licensed premises in the UK. These culminated in the Defence of the Realm Act of August 1914, which along with the introduction of rationing, and the censorship of the press also restricted the opening hours of public houses to 12noon–2.30pm and 6.30pm–9.30pm. Opening for the full licensed hours was compulsory, and closing time was equally firmly enforced by the police; a landlord might lose his licence for infractions. During the twentieth century, both the licensing laws and enforcement were progressively relaxed, and there were differences between parishes; in the 1960s, at closing time in Kensington at 10.30pm, drinkers would rush over the parish boundary to be in good time for "Last Orders" in Knightsbridge before 11pm, a tradition observed in many pubs adjoining licensing area boundaries. Some Scots and Welsh parishes remained officially "dry" on Sundays (although often this merely required knocking at the back door of the pub). However, closing times were increasingly disregarded in the country pubs. In England and Wales by 2000 pubs could legally open from 11am (12 noon on Sundays) through to 11pm (10.30pm on Sundays). That year was also the first to allow continuous opening for 36 hours from 11am on New Year's Eve to 11pm on New Year's Day. In addition, many cities had by-laws to allow some pubs to extend opening hours to midnight or 1am, whilst nightclubs had long been granted late licences to serve alcohol into the morning.

Scotland's and Northern Ireland's licensing laws have long been more flexible, allowing local authorities to set pub opening and closing times. In Scotland, this stemmed out of a late repeal of the wartime licensing laws, which stayed in force until 1976.

The Licensing Act 2003, which came into force on November 24, 2005, aimed to consolidate the many laws into a single act. This now allows pubs in England and Wales to apply to the local authority for opening hours of their choice. This has proved controversial, with supporters arguing that it will end the concentration of violence around half past 11, when people must leave the pub, making policing easier. Critics have claimed that these laws will lead to '24-hour drinking'. By the day before the law came into force, 60,326 establishments had applied for longer hours, and 1,121 had applied for a licence to sell alcohol 24 hours a day [2]. However, many argue that few of these establishments will be constantly open.

Pub games and sports

Numerous traditional games are played in pubs, ranging from the well-known darts and bar billiards, to the more obscure Aunt Sally, nine men's morris and ringing the bull. Betting is legally limited to certain games such as cribbage or dominoes, but these are now rarely seen. In recent decades the game of pool (both the British and American versions) has increased in popularity, other table based games such as Table Football are also common.

Increasingly, more modern games such as video games and slot machines are provided. Many pubs also hold special events, from tournaments of the aforementioned games to karaoke nights to pub quizzes. Some play pop music, or show football and rugby on big screen televisions. Despite the wide range of distractions now available in pubs, doing nothing other than drinking and talking remains perfectly acceptable. Shove ha'penny was also popular in pubs south of London. Darts played in pubs on the Isle of Dogs London had no "Triple" numbers slot, Only "Double".

English Pub food

Traditionally pubs in England were drinking establishments and little emphasis was placed on the serving of food, usually called 'bar snacks'. The usual fare consisted of specialised English snack food such as pork scratchings, pickled eggs, along with crisps and peanuts — salted snacks sold or given away to increase customers' thirst. If a pub served meals they were usually basic dishes such as a ploughman's lunch. In South East England (especially London) it was common until recent times for vendors selling cockles, whelks, mussels and other shellfish to sell to customers during the evening and at closing time. Many mobile shellfish stalls would set up near to popular pubs, a practice that continues in London's East End.

Starting in the 1990s, however, food became a much more important contributor to the income of pubs, and today many serve lunches and dinners at the table (colloquially this is known in England as pub grub) in addition to (or instead of) snacks consumed at the bar: they may even have a separate dining room. Some pubs are considered to rival good restaurants and are often called gastropubs. The growth in importance of food, and the appeal of eating informally in a pub rather than in a restaurant, has led to some establishments giving all tables over to food and even removing the bar stools.

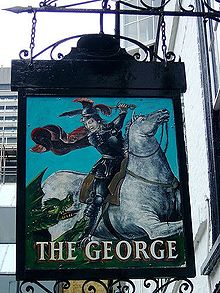

British Pub signs

In 1393 King Richard II compelled landlords to erect signs outside their premises. The legislation stated "Whosoever shall brew ale in the town with intention of selling it must hang out a sign, otherwise he shall forfeit his ale." This was in order make them easily visible to passing inspectors of the quality of the ale they provided.

Another important factor was that during the Middle Ages a large percentage of the population would have been illiterate and so pictures were more useful than words as a means of identifying a public house. For this reason there was often no reason to write the establishment's name on the sign and inns opened without a formal written name—the name being derived later from the illustration on the public house's sign. In this sense, a pub sign can be thought of as an early example of visual branding.

The very earliest signs were often not painted but consisted, for example, of paraphernalia connected with the brewing process such as bunches of hops or brewing implements, which were suspended above the door of the public house. In some cases local nicknames, farming terms and puns were also used. Local events were also often commemorated in pub signs.

Simple natural or religious symbols such as the 'The Sun', 'The Star' and 'The Cross' were also incorporated into pub signs, sometimes being adapted to incorporate elements of the heraldry (e.g. the coat of arms) of the local lords who owned the lands upon which the public house stood. Some pubs also have Latin inscriptions (see image).

Other favourite subjects which lent themselves to visual depiction included the name of great battles (e.g. Trafalgar), explorers, local notables, discoveries, sporting heroes and members of the royal family. Some pub signs are in the form of a pictorial pun or rebus. For example, a pub in Crowborough, UK called The Crow and Gate has an image of a crow with gates as wings.

In the modern era most British pubs still have highly decorated signs hanging over their doors, and these retain their original function of enabling the rapid identification of the public house—a memorable and prominently located pub sign is still an important means of picking up passing trade. Today's pub signs almost always bear the name of the pub, both in words and in pictorial representation.

Pub names

Pubs often have traditional names. Here is a list of categories:

- relating to its location: The Three Arrows, The Cross, The Railway, The Church

- reflecting local trades or related to the pub's clientele: The Mason's Arms, The Foresters, The Square and Compass

- ironic descriptions of the pub itself: the smallest pub in Britain is called The Nutshell

- local sporting activities: The Cricketers, The Fox and Hounds, The Fighting Cocks

- a noted individual: The Marquis of Granby (see below), The Lord Nelson, The Emma Hamilton

- an historic event: The Trafalgar, The Royal Oak

- often incorporating the word 'Head'; The King's Head, The Queen's Head, The Sultan's Head

- alluding amusingly to everyday phrases: The Nowhere Inn Particular (now closed, see picture), The Dewdrop Inn, The Drift Inn (known locally as the "stagger oot"), Down The Hatch

- with a royal or aristocratic association: The Royal Standard, The King's Arms, The King's Head, The Queen Victoria, The Duke of Cambridge,The Anglesea Arms

- with the names of two objects which may or may not be complementary: The George and Dragon, The Goat and Compasses (humorous corruption of the puritan phrase "God encompass" of the 1600s in England), The Rose and Crown, The Dog and Handgun, The Elephant and Castle, The Crow and Gate, The Rummer and Grapes, The Shoulder of Mutton and Cucumbers.

- The surname of its landlord, particularly in Ireland: O'Neill's, Tí hAnraí (Henry's house).

- with names of tools or products of trades: The Harrow, The Propeller, The Wheatsheaf

- with names of items, particularly animals, that may be part of a coat of arms (heraldic charges): The Red Lion, The Unicorn, The White Bear.

- with reference to history of the local area, for example The Strugglers in Lincoln refers to how people being publicly executed by hanging would struggle for air. Ironically the famous executioner Albert Pierrepoint was landlord of the Help the Poor Struggler at Hollinwood, near Oldham, for several years after WW2, and had to hang one of his own regulars, James Corbitt. Also Ye olde Trip to Jerusalem, purportedly the oldest public house in England (Nottingham, 1189), refers to its role as a resting place for the knights of Richard I on their way to the third crusade.

A very common name is the "Marquis of Granby". John Manners, Marquess of Granby was the son of John Manners, 3rd Duke of Rutland) and a general in the 18th century British Army. He showed a great concern for the welfare of his men, and on their retirement, provided funds for many of them to establish taverns, which were subsequently named after him.

Many names for pubs that appear nonsensical may have come from corruptions of older names or phrases, often producing a visual image to signify the pub. For example, the name The Goat and Compasses is a corruption of the phrase "God encompasseth us". These images had particular importance for identifying a pub on signs and other media before literacy became widespread. Another example of a mistaken pub name is the Oyster Reach pub in Ipswich, England. This pub spent several decades being called the Ostrich, before historians informed the owners of the original name. More possible but uncorroborated corruptions include "The Bag o'Nails" (Bacchanals), "Elephant and Castle", (Infanta de Castile) and "The Bull and Bush", which purportedly celebrates the victory of Henry VIII at "Boulougne Bouche" or Boulougne Harbour. While these corruptions are amusing there are usually more substantiated explanations available.

A too-obviously humorous name is likely to be a recent coining of a marketing executive, rather than traditional. This is especially true for names with unsubtle double-entendres or names which have elements common to all the pubs in a particular chain (eg "XXXX and Firkin").

Tied houses and free houses in Britain

After the development of the large London porter breweries in the 18th century, the trend grew for pubs to become tied houses which could only sell beer from one brewery (a pub not tied in this way was called a "Free House"). The usual arrangement for a tied house was that the pub was owned by the brewery but rented out to a private individual (landlord) who ran it as a separate business (even though contracted to buy the beer from the brewery). A growing trend in the late 20th century was for the brewery to run their pubs directly, employing a salaried manager (who perhaps could make extra money by commission, or by selling food).

Most such breweries, such as the regional breweries Shepherd Neame in Kent and Youngs in London, control hundreds of pubs in a particular region of the UK, whilst a few, such as Greene King, are spread nationally. The landlord of a tied pub may be an employee of the brewery—in which case he would be a manager of a managed house, or a self-employed tenant who has entered into a lease agreement with a brewery, a condition of which is the legal obligation (trade tie) only to purchase that brewery's beer. This tied agreement provides tenants with trade premises at a below market rent providing people with a low-cost entry into self-employment. The beer selection is mainly limited to beers brewed by that particular company. A Supply of Beer law, passed in 1989, was aimed at getting tied houses to offer at least one alternative beer, known as a guest beer, from another brewery.This law has now been repealed but while in force it has dramatically altered the whole industry and it is hard to see how the consumer has actually benefited from this change.

A free house is, strictly, simply a pub that is free of the control of any one particular brewery. But "Free" in this context does not necessarily mean "independent", and the view that "free house" on a pub sign is a guarantee of a quality, range or type of beer available is a mistake. Many free houses are not independent family businesses but are owned by large pub companies. In fact, these days there are very few truly free houses, either because a private pub owner has had to come to a financial arrangement with a brewer or other company in order to fund the purchase of the pub, or simply because the pub is owned by one of the large pub chains and pub companies (PubCos) which have sprung up in recent years. Some chains have rather uniform pubs and products, some allow managers some freedom. One of the largest pub chains does sell large amounts of a wide variety of real ale at low prices - but its pubs are not specifically "real ale pubs", being in the city centre to attract the Saturday night crowds and so also selling large quantities of alcopops and big-brand lager to large groups of young people.

Of course, even a truly independent free house may just sell keg beer if that is the landlord's view of what beers will suit local taste. However, the "specialist" real ale pubs, often found just outside the city's inner ring road, where rents are lower, where the binge lager drinkers do not reach, where people from outside town need a good pub or beer guide to find it, and where fruit machines and juke boxes are unknown (to allow people to chat comfortably over their beer), are usually either genuine free houses, or belong to one of the smaller chains which do specifically cater for the "real ale crowd".

British Pub Companies and Pub Chains

Organisations such as Wetherspoons and Eerie, were formed in the UK since changes in legislation in the 1980s necessitated the break-up of many larger tied estates. A PubCo is a company involved in the retailing but not the manufacture of beverages, while a pub chain may be run either by a PubCo or by a brewery. If the owning company is NOT a brewery, then the pub is technically a free house, however limited the manager is in his/her beer-buying choice. Pubs within a chain will usually have lots in common, such as fittings, promotions, ambiance and range of food and drink on offer. A pub chain will position itself in the marketplace for a target audience. One company may run several pub chains aimed at different segments of the market. Pub chains are successful, though some people object that they do not reflect local history and customs. Pubs for use in a chain are bought and sold in large units, often from regional breweries which are then closed down. Newly acquired pubs are often renamed by the new owners, and many people resent the loss of traditional names, especially if their favourite regional beer disappears at the same time. A small number of pub chains (usually small ones) are noted for the independence they grant their managers, and hence the wide range of beers available.

Pubs in British popular culture

Inns and taverns feature throughout English literature and poetry, from Chaucer onwards. All the major soap operas on British television feature a pub, with their 'pub' becoming a household name. The Rovers Return is the pub on Coronation Street, the British 'soap' broadcast on ITV. The Queen Vic (short for the Queen Victoria) is the pub on EastEnders, the major 'soap' on BBC One, while The Bull in The Archers and the Woolpack on Emmerdale are also central meeting points. The sets of each of the three major television soap operas have been visited by royalty, including Queen Elizabeth II. The centrepiece of each visit was a trip into the Rovers, the Vic or the Woolpack to be offered a drink.

Much of the plotline in British film Shaun of the Dead involves the characters trying to reach their local public house, The Winchester, to escape a zombie invasion. Shaun (Simon Pegg) and Ed (Nick Frost) advocate the pub as the perfect location to wait for help because it is safe, familiar, and they can have a drink and smoke.

British comedian Al Murray's best-known character is a comic right-wing bigot, The Pub Landlord, not necessarily a faithful representation of the typical southern-English pub landlord.

US president George W. Bush fulfilled his ambition of visiting a 'genuine English pub' during his November 2003 state visit to the UK when he had lunch and a pint of non-alcoholic lager with British Prime Minister Tony Blair at the Dun Cow pub in Sedgefield, County Durham.

Pub music

While many pubs now play piped pop music, the Pub has historically been a popular venue for live song. See:

The pub has also been celebrated in popular music. Examples are "Hurry Up Harry" by the 1970s punk rock act Sham 69, the chorus of which was the chant "We're going down the pub" repeated several times. Another such song is "Two Pints Of Lager and a Packet of Crisps Please!" by UK punk band Splodgenessabounds.

As a reaction against piped music, the Quiet Pub Guide was written, telling its readers where to go to avoid piped music.

Theme pubs

Pubs that cater for a niche audience, such as sports fans or people of certain nationalities are known as theme pubs. Examples of theme pubs include sports bars, rock pubs, biker pubs, goth pubs, strip pubs and Irish pubs (see below).

In the U.S., almost all drinking establishments called "pubs" are simply bars with an Irish or British theme.{fact}

Irish public houses

Superficially there is little difference between an Irish pub and its English counterpart. However, closer scrutiny will reveal some differences. Pub frontages are generally plainer and less ornamented than their English counterparts, and hanging signs are absent, with the name of the pub or proprietor being displayed above the door. The use of the term "bar" for a pub is more common in Ireland than in England.

The social and economic role of the pub in Ireland has changed considerably over the last century. Prior to the 1960s and the arrival of supermarket and grocery chains in the country; Irish pubs usually operated as a 'Spirit grocery', combining the running of pub with a grocery, hardware or other ancillary business on the same premises (in some cases, publicans also acted as undertakers, and this unusual combination is still common today in the Republic of Ireland)[3][4]. A well-known pub in Abbeyleix, Morrisey's, is representative of the traditional spirit grocers. Spirit groceries first appeared in the mid 18th Century, when a growing temperance movement in Ireland forced publicans to diversify their businesses to compensate for declining spirit sales. With the arrival of increased competition in the retail sector, many pubs lost the retail end of their business and concentrated solely on the licensed trade. Many pubs in Ireland still resemble grocer's shops of the 19th Century, with the bar counter and rear shelving taking up the majority of the space in the main bar area, apparently leaving little room for customers. This seemingly counter-productive arrangement is a design artefact dating from prior operation as a spirit grocery, and also accounts for the differing external appearance of English & Irish Pubs. Spirit Grocers in Northern Ireland were forced to choose between the retail or licensed trades upon the partition of Ireland in 1922, and this pub type can no longer be found there.

In contrast to England, Ireland's pubs usually bear the name of the current or a previous owner, e.g. Murphy's or O'Connor's, and traditional pub names are absent. Famous traditional pubs in Dublin which have the characteristics outlined above include O'Donoghue's, Doheny & Nesbitt's & the Brazen Head, which bills itself as Ireland's oldest pub (a distinction it shares with several other pubs). Some pubs are named after famous streets such Sober Lane in Cork which is named after Father Matthew's Hall of Abstinence. Individual pubs are also associated with famous Irish writers and poets such as Patrick Kavanagh, Brendan Behan and James Joyce.

Pubs in Northern Ireland are largely identical to their southern counterparts. A side effect of the 'Troubles' was that the lack of a tourist industry meant that a comparatively higher proportion of traditional bars have survived the wholesale refitting of Irish pub interiors in the English style in the 1950s and 1960s. This refitting was driven by the need to expand seating areas to accommodate the growing numbers of tourists, and was a direct consequence of the growing dependence of the Irish economy on tourism. Famous traditional pubs in Belfast include the National Trust's Crown Liquor Saloon, and the city's oldest bar, McHugh's. Outside Belfast, pubs such as the House of McDonnell in Ballycastle (a former spirit grocery retaining all the characteristics of the type) and Grace Neill's in Donaghadee are representative of the traditional country pub.

The pubs listed above are notable as being truly representative of the traditional Irish type (while some may have been expanded, the original bar areas have been retained in all cases), as few remain today after the extensive refitting noted above. The majority of 'traditional' pubs in Ireland today have been refurbished in a pastiche of the original style during the 1990s. Many Irish pubs were refurbished in this manner so as to increase their attractiveness to tourists by more closely resembling the 'Irish pubs' found outside Ireland; and thus have more in common with them (many were refurbished by the same outfitting companies) than the traditional pub type they purport to represent.

The sentimental image of Ireland held by many tourists and members of the Irish diaspora has also resulted in changes to the Irish pub experience in many areas. The notion that there is more live music in an Irish pub, and that a customer is more likely to entertain the assembly with a song is a myth created and actively promoted by the Irish tourist industry. Pubs of this type (so-called 'singing pubs') are more likely to be found in areas dependent on tourism such as the south-west of Ireland. These pubs are conspicuously absent in areas where tourism is not a major part of the local economy, such as the midlands or border counties. 'Singing pubs' are also absent from Northern Ireland. Pubs in tourist oriented areas are also more likely to serve food to their customers, a recent phenomenon dating from the 1970s. Prior to this time food was not served in the vast majority of Irish pubs, as eating out was uncommon in Ireland (except in "eating-houses" set up on market days) and most towns and villages had at least one commercial hotel where food was available throughout the day [5]. The provision of meals in pubs since this time is largely the result of an effort by Irish publicans to capture an increased revenue stream from the tourist sector (where such revenue is available). The majority of traditional rural pubs not on the major tourist trails retain this characteristic and do not serve food; while traditional bars in urban areas such as Dublin, Armagh, Galway, and Sligo have responded to the increase in Irish people eating outside the home (a by-product of so called 'Celtic Tiger' economy during the 1990s); and now provide meals throughout the day.

The smoking ban in the Republic has noticeably changed the Irish pub experience; many pubs now offer enclosed and often heated outdoor smoking areas. While many people object, the greater majority of people appear content with the legislation, which will come into effect in Northern Ireland in April 2007.

Irish Pubs have been opened throughout the world, particularly in the 1980s and 1990s, from Boston to Frankfurt, Johannesburg to Beijing. While ubiquitous, they generally have little in common with pubs in Ireland.

The vast majority of pubs in Ireland are independently owned and licensed, or owned by a chain who do not have any brewery involvement, generally meaning that nearly every pub sells a similar but extensive range of products. Some micro-breweries operate their own pubs or chains of pubs, where the range is more limited, with only their own products and a few others.

Compare with

- Bar

- Biergarten (aka Beer garden)

- café

- Coffeehouse

- Inn

- Izakaya

- Kopi tiam, coffee shop

- Restaurant

- Tavern

- Beer hall, a German pub

See also

- Australian pubs

- Notable British public houses

- Pub sports

- Beer garden

- Pub games

- Evening Standard Pub of the Year, an annual award in London

- Pub chain

- Pub crawl

- Tied house

- Free house

- cider house

- Pub Grub

External links

- Pubs Slideshow — Photos of 'Pubs of London' By Jim at SnapGalaxy!!

- The Real English Pub — An English themed forum where everyone is welcome to join us!

- Pubs in London — A historical & genealogical listing of around 8000 Pubs in London, Essex, Middlesex, Surrey & Kent over the last 200 years — you are welcome to add some detail.

- Irish Pubs in France — Listing of all Irish Pubs in Paris and throughout France.

- Congleton's Ancient Inn Signs Travested — Congleton's pubs from 1932

- UKcider wiki pub guide A wiki guide to more than 850 UK pubs that server real cider

- Ant Veal's Top UK Pubs A personally written guide to over 200 classic traditional British pubs selling top quality real ale

Notes

- ^ Fiona MacDonald, The Plague and Medicine in the Middle Ages, p7, ISBN 0836859073

References

- Beer and Britannia: An Inebriated History of Britain by Peter Haydon (2001, Sutton)

- Beer: The Story of the Pint by Martyn Cornell (2003, Headline)

- The English Pub by Michael Jackson (1976, Harper & Row).

- The Australian Crawl - A Guide to the Pubs Of Regional Australia, Scott Watkins-Sully, (2006, ABC Books)