Kepler-56

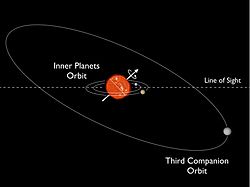

Graphical sketch of the Kepler-56 system. The line of sight from Earth is illustrated by the dashed line, and dotted lines show the orbits of three detected companions in the system. The solid arrow marks the rotation axis of the host star, and the thin solid line marks the host star equator. Credit: NASA GSFC/Ames/D Huber | |

| Observation data Epoch J2000.0[1] Equinox J2000.0[1] | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Cygnus |

| Right ascension | 19h 35m 02.0012s[4] |

| Declination | +41° 52′ 18.692″[4] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 13 |

| Characteristics | |

| Evolutionary stage | red giant[5] |

| Spectral type | K3III |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | -53.740601[1] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: −6.596(12) mas/yr[4] Dec.: −12.081(13) mas/yr[4] |

| Parallax (π) | 1.0755 ± 0.0118 mas[4] |

| Distance | 3,030 ± 30 ly (930 ± 10 pc) |

| Details[5] | |

| Mass | 1.286±0.011 M☉ |

| Radius | 4.179±0.132 R☉ |

| Luminosity (bolometric) | 9.589±0.129 L☉ |

| Temperature | 4973±14 K |

| Metallicity [Fe/H] | 0.0251±0.013 dex |

| Age | 3.917±0.157 Gyr |

| Other designations | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

Kepler-56 is a red giant[6] in constellation Cygnus roughly 3,030 light-years (930 pc) away[4] with slightly more mass than the Sun.

Characteristics

Kepler-56 is a red giant star. This means it is no longer fusing hydrogen in its core and is off the main sequence. Its mass is around 1.3 M⊙. Its radius is about 4.2 R⊙, putting the star's density at about 0.025 g/cm3. For reference, the Sun's density is about 1.408 g/cm3. Its metallicity is about 0.0251 Z0/X0. Its luminosity is about 9.6 L⊙, and its effective temperature is 4,973 K (4,700 °C; 8,492 °F), classifying Kepler-56 as spectral class K3III.[5]

Kepler-56 is about 3.9 billion years old,[5] placing it as about 600 million years younger than our Sun. Its apparent magnitude is +13, making it too dim to be visible to the naked eye.

Planetary system

In 2012, scientists discovered a two-planet planetary system around Kepler-56 via the transit method. Asteroseismological studies revealed that the orbits of Kepler-56b and Kepler-56c are coplanar but about 45° misaligned to the host star's equator. In addition, follow-up radial velocity measurements showed evidence of a gravitational perturbator.[6] It was confirmed in 2016 the perturbations are caused by third, non-transiting planet: Kepler-56d.[7]

The planetary system is very compact but is dynamically stable.[8]

Kepler-56 is expanding. As a result, it will devour Kepler-56b and Kepler-56c in 130 and 155 million years, respectively.[9][10] 56d will be far enough to survive its parent star's red giant phase.

| Companion (in order from star) |

Mass | Semimajor axis (AU) |

Orbital period (days) |

Eccentricity | Inclination | Radius |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b[2][11] | 0.07 MJ | 0.1028 | 10.5034294 | — | 79.640° | 3.606495320 R🜨 |

| c[3][12] | 0.569 MJ | 0.1652 | 21.4050484 | — | 81.930° | 7.844702558 R🜨 |

| d[7] | >5.61±0.38 MJ | 2.16±0.08 | 1002±5 | 0.20±0.01 | — | — |

References

- ^ a b c "Kepler-56". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg.

- ^ a b "Planet Kepler-56 b". Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia. Retrieved 2013-10-18.

- ^ a b "Planet Kepler-56 c". Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia.

- ^ a b c d e Vallenari, A.; et al. (Gaia collaboration) (2023). "Gaia Data Release 3. Summary of the content and survey properties". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 674: A1. arXiv:2208.00211. Bibcode:2023A&A...674A...1G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202243940. S2CID 244398875. Gaia DR3 record for this source at VizieR.

- ^ a b c d Fellay, L.; Buldgen, G.; et al. (October 22, 2021). "Asteroseismology of evolved stars to constrain the internal transport of angular momentum". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 654. 12. arXiv:2108.02670. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202140518. S2CID 239652877. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- ^ a b Huber, Daniel; Carter, Joshua; et al. (October 21, 2013). "Stellar Spin-Orbit Misalignment in a Multiplanet System". Science. 342 (6156): 331–334. arXiv:1310.4503. Bibcode:2013Sci...342..331H. doi:10.1126/science.1242066. PMID 24136961. S2CID 1056370.

- ^ a b Otor, Oderah Justin; Montet, Benjamin T.; et al. (22 September 2016). "The Orbit and Mass of the Third Planet in the Kepler-56 System". The Astronomical Journal. 152 (6). Cornell University: 165. arXiv:1608.03627v2. doi:10.3847/0004-6256/152/6/165. ISSN 0004-6256.

- ^ Denham, Paul; Naoz, Smadar; et al. (29 October 2018). "Hidden planetary friends: on the stability of two-planet systems in the presence of a distant, inclined companion". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 482 (3): 4146–4154. arXiv:1802.00447. doi:10.1093/mnras/sty2830. ISSN 0035-8711.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Kramer, Miriam (June 10, 2014). "Chow Down! Star Will Devour 2 Alien Planets". Space.com. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ Li, Gongjie; Naoz, Smadar; et al. (October 1, 2014). "The Dynamics of the Multi-planet System Orbiting Kepler-56". The Astrophysical Journal. 794 (2): 131. arXiv:1407.2249. Bibcode:2014ApJ...794..131L. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/794/2/131. S2CID 56224888.

- ^ "KOI-1241.02 -- Extra-solar Confirmed Planet". SIMBAD.

- ^ "KOI-1241.01 -- Extra-solar Confirmed Planet". SIMBAD.

External links