2020 Minneapolis park encampments

Encampment in Powderhorn Park, July 20, 2020 | |

| Duration | June 10, 2020 – January 7, 2021[1] |

|---|---|

| Venue | Minneapolis parks and public property |

| Location | Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States |

| Also known as | "Sanctuary sites" |

| Type | Tent city |

| Cause |

|

| Budget | |

| Organised by | Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board |

| Participants | Volunteers |

| Outcome | Permitted encampments closed January 7, 2021;[5] permits not renewed for 2021[2] |

| Deaths | |

| Website | www |

The U.S. city of Minneapolis featured officially and unofficially designated camp sites in city parks for people experiencing homelessness that operated from June 10, 2020, to January 7, 2021.[1] The emergence of encampments on public property in Minneapolis was the result of pervasive homelessness, mitigations measures related to the COVID-19 pandemic in Minnesota, local unrest after the murder of George Floyd, and local policies that permitted encampments.[8] At its peak in the summer of 2020, there were thousands of people camping at dozens of park sites across the city. Many of the encampment residents came from outside of Minneapolis to live in the parks.[1] By the end of the permit experiment, four people had died in the city's park encampments,[1] including the city's first homicide victim of 2021, who was stabbed to death inside a tent at Minnehaha Park on January 3, 2021.[9]

The encampment crisis grew out of civil unrest following the murder of George Floyd, a Black man, while under arrest by a Derek Chauvin, a White officer from the Minneapolis Police Department on Memorial Day on May 25, 2020. A period of intense protests, riots, and property destruction from May 26 to 30, 2020—largely concentrated on East Lake Street in Minneapolis—resulted in the deployment of the Minnesota National Guard and nightly curfews to keep demonstrators off the streets. Though homeless people were exempt from curfew orders, volunteers helped about 200 unsheltered persons take up residence at an unoccupied Sheraton Hotel in the city's Midtown neighborhood.[10] After several overdoses, one death, violence, and fires, occupants of the hotel were evicted by the hotel's owner, and volunteers helped establish an encampment in the city's Powderhorn Park. Growth of the Powderhorn Park encampment and several safety issues resulted in controversy, and by July 2020 the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board established a permit process to restrict the size of camps.[11]

By mid July 2020, the situation was described as having grown out of the control of park board officials, as encampments spread to unpermitted park sites and other locations throughout the city. Like the camp at Powderhorn Park, many other camp sites had shootings, rampant drug use, sexual assaults, sex trafficking, and other safety issues.[12][13][11][1] The city's social programs attempted to connect people experiencing homeless with services, including establishing three new shelters, but shelter beds remained available during the project. City officials adopted a de-escalation for disbanding camps due to the ongoing civil unrest, and when they attempted to remove tents at non-permitted sites, they faced opposition from a sanctuary movement and protest groups.[14]

Encampments appeared at 44 park sites during the summer months, according to the park board, or at as many as 55 park sites, according to news media reports.[15][1] Park board officials set a deadline to close all encampments by October 2020, and then shifted the deadline to before the onset of freezing temperatures brought on by winter weather. Fifty-three tents, however, remained at three encampments by early December 2020 as some encampment residents declined available shelter space.[16] It was not until January 7, 2021, that the last official encampment, at the city's Minnehaha Park, closed.[1][9][2]

Background

Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board

The Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board is an elected, semi-autonomous local agency that governs the city's park system. Residents in the city elect nine park board commissioners, from six park districts and three at-large, to four-year terms.[17] In 2017, voters elected Chris Meter (District 1), Kale Severson (District 2), AK Hassan (District 3), Jono Cowgill (District 4), and Steffanie Musich (District 5) to district seats, and they elected Meg Forney, LaTrisha Vetaw, and Londel French to at-large seats. The commissioners elected Cowgill as their board president and Vetaw as their vice president.[18] In 2019, the park board commissioners selected Al Bangoura as the park's superintendent to lead a staff of 580 full-time and 1,500 part-time employees, manage an annual budgetary resources of $125 million, and oversee the Minneapolis Park Police Department, a separate law enforcement entity from the Minneapolis Police Department.[19] By the 2020s, the Minneapolis park system had been consistently considered among the most well-regarded in the United States.[20]

Homelessness in Minnesota

A study by the Amherst H. Wilder Foundation, a Saint Paul-based non-profit organization, counted 11,371 people in Minnesota were experiencing homelessness on one night in October 2018. Wilder also estimated that nearly 19,600 people experienced homelessness on any given night in the state, and that a total of 50,600 experienced homelessness in Minnesota at some point during 2018.[13] Black and American Indian people were disproportionately affected. Approximately 66% of those homeless in Minnesota were estimated to be People of Color.[21] Hennepin County estimated in 2019 that it had 10,000 experiencing homeless with 4,000 of them in its largest city, Minneapolis, and it had as many as 800 people living on the street in the county.[22] A report by the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism said by that January 2020 there were 642 people who were unsheltered in Minneapolis, an increase from 603 the prior year and five-fold increase from 2015.[23]

COVID-19 pandemic in Minnesota

The first confirmed case in Minnesota of SARS-CoV-2, the virus causing the coronavirus disease, was reported on March 1, 2020. After detecting the first confirmed case of community spread of SARS-CoV-2 in the state, Governor Tim Walz announced the first of several executive orders to address the COVID-19 pandemic in Minnesota. On March 16, 2020, Executive Order 20-04 closed all non-essential businesses and services until March 27, 2020;[24] subsequent orders required state residents to shelter in place and extended the timeframe for statewide closures for schools and non-essential services.[25][26][27] On March 23, 2020, Executive Order 20-14 suspended home evictions during the pandemic.[28][2] On May 13, 2020, Executive Order 20-55 prohibited sweeps or disbandment of homeless encampments.[29][8]

Civil disorder in Minneapolis

Protest emerged on May 26, 2020, in Minneapolis as a response to murder of George Floyd, a 46-year-old African-American man who died on May 25 after Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin knelt on Floyd's neck for several minutes during an arrest.[30][31][32] Over a three-night period from May 27 to May 29, Minneapolis sustained extraordinary damage from rioting and looting—largely along a 5-mile (8.0 km) stretch of Lake Street south of downtown[33]—including the demise of the city's third police precinct building, which was overrun by demonstrators and set on fire.[34] By early June 2020, approximately 1,300 properties in Minneapolis were damaged by the rioting and looting,[35] of which nearly 100 of which were entirely destroyed.[36]

Timeline

"Camp quarantine"

In early April 2020, several people experiencing homelessness took up residence at a small encampment of about a dozen tents in Minneapolis under the Martin Olav Sabo Bridge, near Hiawatha Avenue and the Midtown Greenway bike and pedestrian trail. The encampment garnered the nickname "camp quarantine"[37][6] as residents felt safer from the coronavirus by living outside on public property than staying in crowded shelters,[38] and they preferred to hang around the camps as the places they had previously visited during the day, such as libraries and public buildings, were closed under the state's public health mitigation of COVID-19.[38]

With fears of the coronavirus on the rise, and 40 cases being reported in homeless shelters, the encampment grew to approximately 100 residents by May 2020.[37][38] An initial emergency executive order by Governor Tim Walz emboldened those dwelling at the encampment as it prohibited local government agencies from closing camps.[37] To limit growth of the camp, Metro Transit officials erected a fence around it, but declined to clear the camp fearing that action might pose greater health and safety risk.[38] Officials also wanted to avoid repeat of the "Wall of the Forgotten Natives," a sprawling encampment in 2018 along a Hiawatha Avenue sound barrier that had near-daily occurrences of overdoses and violence.[37] Walz's revised executive order in early May 2020 allowed encampments to be cleared if they "reached a size or statutes" and posed a health and safety risk to people living there.[37]

On May 25, 2020, George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, died while being pinned to the ground by Derek Chauvin, a White Minneapolis policer who knelt on Floyd's neck as he pled for his life and lost consciousness. Video of Floyd's murder quickly circulated in the media. Protests that emerged on May 26 were initially peaceful, but devolved into widespread rioting and looting, largely concentrated on East Lake Street in Minneapolis over the next several days. Many businesses closed and boarded up their windows and doors to prevent looting and property destruction.[1]

On May 28, 2020, Governor Walz activated the Minnesota State Patrol and the Minnesota National Guard, in what would becomes its largest deployment since World War II, to restore order in Minneapolis and Saint Paul. On May 29, 2020, Walz imposed a metropolitan-wide curfew to keep people off the streets from the hours of 8:00 p.m. to 6:00 a.m., and Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey issued an overlapping city curfew to align with the governor's order.[39] Those breaking curfew faced fines of up to $1,000 or 90 days in jail.[40] Curfews were enforced with mass arrests, including of several journalists, and groups of demonstrators were fired upon by state patrol officers with less-lethal rounds.[41] The curfew orders were originally intended to last two nights, but were extended due to continued unrest. As until nights grew calmer, the curfews finally ended on June 5, 2020.[42]

People experiencing homelessness were exempt from curfew orders, but worries grew that residents of encampments could be swept up in the unrest and potentially shot at with rubber bullets and tear gas.[6] A non-profit organization helped approximately 70 people from the Hiawatha Avenue encampment move to a hotel outside Minneapolis, but some residents remained behind in the encampment, many of who eventually made their way to an activist-led shelter at the Sheraton Midtown Hotel.[43]

"Sanctuary hotel"

In 2020, the Sheraton Minneapolis Midtown Hotel was a four-story, 136-room hotel on Chicago Avenue in the Midtown neighborhood of Minneapolis, abutting the Midtown Greenway bike and pedestrian trail, and located a block north of East Lake Street. Owned by Jay Patel since February of that year, the hotel was a franchise of the international Sheraton Hotel chain.[6]

Activists occupy hotel

As protests and riots spread in Minneapolis after Floyd's murder, including widespread property destruction along the East Lake Street corridor and destruction of the nearby third precinct police station,[22][33] Patel evacuated guests from the hotel the night of May 30, 2020, as his insurance company would no longer cover the hotel building if people continued to occupy it.[43][6]

Activists who worked with unhoused people, and who were also backed by donations of an anonymous person, negotiated to buy a block of rooms for people displaced by the unrest.[22][6] In agreeing to pay for the rooms, they suggested to Patel that he convince the insurance company that the hotel was taken over by activists without permission. They also said they would help protect the building from arson and looting that had occurred in the area the previous nights.[6] After receiving approval from Patel, the hotel quickly filled to capacity with approximately 190 people who had previously been staying at encampments. As many as 150 volunteers worked shifts to serve food, clean rooms, and operate the hotel, and they gave they project the monikers "sanctuary hotel" and "share-a-ton".[22]

Many volunteers knew each other from prior housing advocacy work in the area.[22] It was reported that though they were excited for the experimental project that was free of government restrictions, though it was established during a chaotic period of time in Minneapolis, and volunteers were concerned that managing the project would be challenging.[22] Some organizers believed that eventually government agencies would take over the project.[43] The volunteers at the hotel were considered a group of mostly White, middle-class activists, but included social service and health care workers. Many of the hotel residents suffered from addiction or mental illness.[6]

The sanctuary was both a place of refuge for unsheltered people for displaced by the riots on East Lake Street, as well as an attempt at police abolition—volunteers believed that residents could police themselves without traditional law enforcement.[6] At the height of the sanctuary hotel's occupancy, the police abolition movement in Minneapolis had taken hold. Several local agencies, including the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board on June 3, had formally dissolved their relationships with the city's police department.[44] Nine of the thirteen members of the city's council pledged at a large rally in Powderhorn Park on June 7 to dismantle the Minneapolis Police Department.[6] Volunteer workers and residents at the hotel pledged not to call law enforcement or allow police officers inside the hotel.[6]

Eviction and closure

After about a week the situation in the hotel descended into chaos with sexual assaults, sex trafficking, armed drug trafficking, rampant drug use, vandalism, violence, and fires.[45][46][6][21] There were at least four overdoses and one death during the sanctuary occupation.[6] Many of the volunteers did not have experience working with vulnerable populations[43] and they were also overwhelmed by the number of people staying there.[43] By June 10, estimates were that 200 to 300 people were living at the hotel.[1]

After hotel rooms filled up, people coming to the hotel seeking a place to stay slept in the lobby, hallways, and conference rooms.[43] Neighbors reported that the lack of controlled entry resulted in people coming in and departing the hotel at all hours of the day. Some who came to the hotel used it as a place to run commercial sex work and drug dealing operations. There were numerous 9-1-1 calls for gunfire, sex trafficking, and drug dealing. Those living in nearby apartments reported seeing rooftop gunfire and fires.[21]

The hotel owner said on June 9 that residents of the hotel would be evicted, and residents began moving out.[43] Volunteers formally ended their role at the hotel, and volunteers supplied camping equipment to some residents and helped move them to camps in the Powderhorn Park and Peavy Field city parks.[22][45][46] Though all volunteers left, sanctuary movement organizers said that the hotel sanctuary would not be closing, and other residents stayed behind.[43] Minneapolis police and community groups eventually cleared the hotel of its last residents on June 15.[21] A leader of MAD DADS, a local community non-profit in Minneapolis, that sought to prevent drug abuse, said about the hotel at eviction, "It was just inhabitable for people. Broken glass, needles everywhere. People were being abused and all kinds of drug use. It was dangerous for families to be in here."[21]

Hennepin County outreach workers helped many people find indoor shelter options who stayed at the hotel. The sanctuary movement, who had organized the project, upon abandoning the hotel led some residents to Powderhorn Park, where they pitched several tents.[13] The owner of the hotel did not end up accepting any money that volunteers had offered to pay for the rooms.[22]

Hotel aftermath

After its closure, the Midtown Sheraton Hotel experiment became a source of controversy for discussions about homelessness and social justice issues. Progressive magazine Mother Jones described the hotel experiment as an "utopian sanctuary". Far right-wing commentators at Gateway Pundit characterized events as the hotel as a "Marxist" movement of rioters and squatters and largely reported on acts of vandalism there.[6] One resident described the hotel environment as "chaotic and unruly".[43] MplsStPaul magazine described the situation by the time residents were evicted as having "disintegrated into a disaster—the hotel overrun with rampant drug use and sex trafficking".[13]

Prior to the eviction of residents at the Sheraton Hotel, organizers admitted they were ill-equipped to manage the situation and made public pleas for government agencies to take over.[43] Organizers of the hotel experiment, as well as project's unintended outcomes, were criticized. Social service providers and organizers of other homeless camps in the city noted the lack of security to control entry, inexperienced volunteers, and lack of oversight of resident activities.[43] The sanctuary movement at the Sheraton Midtown Hotel was also criticized for being a predominately White-led volunteer effort, especially as many of the residents were Black or American Indian.[6] Some volunteers at the hotel felt the effort inadvertently harmed many of the people they tried to serve. As residents were being evicted from the Sheraton Midtown Hotel in early June, activists enlisted the help of local social justice advocacy group Black Visions Collective, but volunteer organizers felt the move came too late and ultimately it did not help the project succeed.[6]

Park encampments

Powderhorn Park

Powderhorn Park is a 66-acre (27 ha) city park in Powderhorn Park, a residential neighborhood in Minneapolis. It is managed by the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board. [47] An encampment emerged first at the park on June 10. Though social service providers attempted to connect people staying at the Sheraton Midtown Hotel with housing options, the sanctuary movement volunteers helped some hotel residents form a 10-tent encampment on Powderhorn Park property. At the time, the superintendent of the park board, Al Bangoura, expressed concern that the violence and other problems that occurred at the hotel would also occur at the park. By June 12, the encampment had more than doubled to 25 tents, with approximately 18 people living there,[21][1] and the park board issued an eviction order. The park, however, was not cleared as the office of Governor Walz intervened and said that executive orders prohibited officials from disbanding it, and some park board members said the encampment should remain.[13][21][1]

Less than one week later, the number of tents increased to 50, between the original camp site and a satellite encampment on the other side of the park, as more people were transported via Metro buses from the Sheraton Midtown Hotel to the park.[21][1] Volunteers, who were unaware that buses would be dropping off more people at the park encampment, were worried the influx of new residents would be disruptive to the culture they had established there.[21] Dozens of unsheltered people soon arrived that had been staying at other hotels paid for donations to the hotel sanctuary project.[21] As the Powderhorn Park encampment quickly grew, outreach workers were worried that a much larger encampment would overwhelm volunteers and be too dangerous for the people living there.[21]

Uncontrolled growth and safety issues

The Powderhorn encampment had grown to grown to 180 tents by June 17. The park board met that night and passed a resolution to allow people to seek refuge in city parks. The board also committed to working with social service providers to identify long-term housing options encampment residents.[1][48] The encampment situation, however, quickly grew out of the control of park board officials.[12] By the end of June, at Powderhorn Park there were 400 total tents between two encampments, and 44 encampments emerged at other parks across the city,[1] some with as many as 300 residents.[2] The park board reported later that many encampment residents had come from outside of Minneapolis to live in the parks.[1]

At Powderhorn Park, numerous sexual assaults, fights, and drug use at the encampment generated alarm for nearby residents and city officials.[11][13] Minneapolis city counselor Alondra Cano had called a community meeting about the encampment, but cancelled it out of safety concerns. A planned voter registration drive by the Democratic-Farmer-Labor party scheduled for June 19 at the encampment was also canceled as the park was not considered safe for volunteers.[49] A juvenile was sexually assaulted at the encampment during the overnight hours on June 26.[50][51] The sexual assault of a woman was reported at the encampment on June 28.[52] Another juvenile was sexually assaulted on July 4.[52][13] Seven other series crimes were reported at the encampment between July 5 and July 13.[53][8]

By mid July the sprawling encampment at Powderhorn Park had grown to 560 tents by with an estimated 800 people living there.[45][46]

Permit process established

On July 14, Governor Walz signed an executive order that modified the eviction moratorium to allow local governments to disband camps for safety concerns, illegal activity, and property damage.[54]

After facing pressure from residents that lived near Powderhorn Park, the park board created a permit process to restrict the size and growth of camps, which was considered major departure from their decision a month prior to allow people to seek refuge on park property.[55] The park board resolution passed on July 16 restricted the number of camps on park property to 20 with a maximum of 25 tents each.[11] Park encampments were to be prohibited within a certain distance of schools and permitted encampments required buffer zones to ensure park visitors were kept safe.[56][12] The resolution also required organizations to sponsor and obtain permits, or the encampments risked being disbanded and residents having belonging removed from camps. The permits did not have a specified end date, but the resolution called for progress towards moving encampment residents to shelters and other housing options.[55][2]

The first permitted encampment opened at Lake Harriet and some others soon followed. By early August, the park board had estimated there were 413 tents across 38 city parks, but local media reported that encampments were noticed at more than 55 parks, with only the four park sites of Lake Harriet, Marshall Terrace Park, The Mall, and Bde Maka Ska at William Berry Park having obtained permits.[15][57] A permit was later granted for an encampment outside Theodore Wirth House, the superintendent's home residence and historic park administration building.[13] The park board also designated a dozen other parks where permits would be allowed if organizations applied for permits: Boom Island, Riverside, Annie Young, BF Nelson, Franklin Steele, Minnehaha Falls, Lyndale Farmstead, Martin Luther King Jr., Bryn Mawr, Beltrami, Logan, and Lake Nokomis parks.[15]

Closure of Powderhorn Park encampments

Following a revision to state executive orders on evictions and the permit process they established, the park board began closing one of the two encampments at Powderhorn Park in late July.[58] City outreach teams worked to connect residents with shelter options. Some displaced Powderhorn Park residents moved to other camps sites in the city,[58] but many refused to leave.[49] The encampment was the source of continued violent crime and drug overdoses.[50][58] From July 15 to early August, thirteen additional violent crimes were reported at Powderhorn Park, including multiple assaults, a rape, arson, and injuries from gunfire.[15][50] The park board moved to close the site and gave residents two weeks to decide between a shelter or being moved to other encampments in the city that had permits, with the city providing transportation. Some residents chose to stay. The park board cleared the 35 remaining tents at Powderhorn Park on August 14, as police faced off with protesters and fired pepper spray, and made two arrests of demonstrators.[59]

At its peak, the Powderhorn Park encampment was considered the largest in the history of the Twin Cities metropolitan history, having 560 tents with an estimated 800 people living it by the end of July.[13] However, there was no agreed upon count of the number of people living at the camp. The park board published a count of the number of tents at Powderhorn Park that it updated daily; the count peaked at about 570 in July. People observing the encampment said there were approximately 1.5 to 1.75 people per tent, with a possible total of over 800 residents. Others said that individual encampment residents had multiple tents and put the person count closer to 250.[49] A separate report by the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism said as many as 700 tents were at Powderhorn Park by July.[23]

Unpermitted encampments

By early August several unpermitted encampments in parks had emerged at Loring, Logan, Lake Nokomis, Elliot, Matthews, Beltrami, and Boom Island parks, among other sites. Social service providers expressed concern that the expansion of encampments were diverting unhoused people away from shelter and more-stable housing options. Some park board members expressed frustration that encampments at Peavey, Powderhorn Park, Kenwood, and Elliot Parks—which had several reported safety and health issues—were not disbanded.[15] In particular, the unpermitted encampment that emerged at Kenwood park drew concern from neighbors due to is proximity to a school and other safety incidents, such when police responded to an indecent exposure incident by a man and a fight that resulted in several arrests, and the 10-tent encampment was later relocated to another section of the same park.[57] A Star Tribune editorial on August 14 said that "Allowing the camps to grow and attract so much illegal activity has endangered not only neighbors and park users, but also the homeless campers themselves. Some of them became victims of criminals, even after they had moved to the camps believing they would be safer outside than in shelters."[60]

Unpermitted encampments were later cleared at Elliot, Kenwood, Matthews, and Loring parks, among others.[13] Some residents were transferred to Franklin Steele Park or other encampment sites.[61]

Peavy Field Park

In late June, an unpermitted encampment emerged at Peavy Field Park, a 7-acre (2.8 ha) youth recreation area and playground in the city's Ventura Village,[47] that drew criticism for safety concerns.[62] The encampment violated the park board's permit resolution as it was located adjacent to the K-12 Hope Academy school that shared the park grounds.[56] On July 1, a teenager was shot multiple times outside the Peavy Park encampment.[63] On July 16, two people were wounded by gunshots at the encampment.[50] On August 11, thirty-five gunshot rounds were fired in Peavy Park, but no one was injured.[64] School staff, parents, and students from K-12 Hope Academy requested the park board clear the encampment so that students could safety return to using the park equipment and fields when school would resume in early September.[56]

The park board issued vacate notices for those staying at the 12-tent encampment on August 10 and attempted to connect those staying there with shelters and social services over the following weeks.[56] Protesters, however, initially blocked officials from clearing the camp.[14] On September 24, the park board disbanded the camp for the five remaining people staying there and cleared the park of abandoned tents, hypodermic needles, and biohazard materials.[56] A group of demonstrators gathered outside the Hennepin County Government Center building in downtown Minneapolis the night of September 24 to protest the encampment's closure. Law enforcement authorities made five arrests of demonstrators; none of those arrested had been staying at the encampment.[62]

"Wall of Forgotten Natives"

On September 3, 2020, a group backed by protesters and American Indian Movement advocates re-occupied a site they referred to as the "Wall of Forgotten Natives" near Hiawatha and Franklin avenues in Minneapolis. The site on Little Earth Trail along Minnesota State Highway 55/Hiawatha Avenue had been barricaded by the state in 2018 when an encampment closed after experiencing drug overdoses, spread of disease, violence, fires, and deaths.[14] The Highway 55 encampment had been linked to four deaths in 2018.[65] In September 2020, reoccupation of the encampment with 40 tents came after the city closed another encampment at Phillips Park on 13th Avenue South due to health and safety concerns, and after officials sought help from nonprofit organizations to house residents. Reestablishment of the Hiawatha encampment also came during time of increasing confrontation between Minneapolis officials and homeless advocates, as the city had hoped to close all encampments by October 2020, but state patrol officers did not intervene when a group cut locks to enter the fenced-off area. Though the city and county had allocated $8 million for three new shelters, including a Native-specific one, advocates were unsatisfied with the response by local officials to the needs of Native homeless persons, and established the camp.[14]

Decline of encampments

The number of people residing in encampments declined as the city moved more people to shelters and hotels.[23] The number of encampments in city parks fell from more than 40 in August to more than 20 by September.[14] Encampments with permits remained in 15 city parks by late September.[13] The park board estimated that there were 222 tents in city parks as of October 15.[4] City officials said they did not have an exact deadline to close encampments, but they said they intended to help connect encampment residents to shelters and close all camps before the onset of cold weather.[4]

In October, the Mid-Minnesota Legal Aid and the American Civil Liberties Union filed a federal lawsuit to prevent closure of homeless encampments in city parks, but it was dismissed by U.S. District Judge Wilhelmina Wright.[66] By the end of November, the park board issued vacate notices for the encampment at The Mall Park along the Midtown Greenway due to several fires, injuries, overdoses, and other violent crimes that were reported there.[67]

In early December, fifty-three tents remained across three encampments: Minnehaha Park, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Park, and The Mall Park. Outreach workers were unable to convince some residents to move to available shelter space.[16][68] On December 10, the park board closed the encampment at The Mall Park, citing health and safety issues, and seven of the eight people residing there declined shelter assistance offered by Hennepin County.[67]

Homicide in Minnehaha Park

By the end of 2020, the last encampment in city parks remained at Minnehaha Park, a 167-acre (68 ha) regional park that was among the city's oldest parks and most visited tourist destinations for its famed waterfall and creek gorge.[69] On December 31 park board officials issued vacate notices to those staying there that would be effective on January 3, 2021. Officials provided encampment residents with five short-term shelter options, but some residents chose to stay at the camp. Activists vowed to protest if residents were evicted and argued that those staying at the encampment had been relatively peaceful, and that they should be allowed to stay.[68] On January 3, 2021, Minneapolis police recovered the body of the 38-year old Sedric L. Dorman inside a tent at the Minnehaha Park encampment. Dorman's death was ruled a homicide, the city's first in 2021, from the multiple stab wounds he sustained early that afternoon.[70][7]

Closure of encampments

Citing "documented health and safety concerns", the park board closed the Minnehaha Park encampment, the last remaining one in city parks, on January 7, 2021.[5]

Activism and protests

Some who volunteered at encampments were motivated by the murder of George Floyd to seek justice on social issues.[71] The Minneapolis Sanctuary Movement, one of the organizations coordinating activities at the Sheraton Midtown Hotel and Powderhorn Park encampment described their purpose as being a "community care experiment fighting for housing justice, abolition, and land reclamation by supporting the most impacted people to take the lead".[72] MplsStPaul magazine described the dynamic as having "lines blurred between sanctuary and rogue activists" who used the circumstances of encampment residents to advance an agenda of social and racial justice, sometimes at the expense of the welfare of unhoused people.[13] In a press conference on September 3, 2020, American Indian activists that helped re-establish the "Wall of Forgotten Natives", an encampment along Hiawatha Avenue/Highway 55, described the encampment as reclaiming lands belonging to Native people prior to European settlement.[14] Some advocates believed citizens had a right to seek refuge on public lands, and felt the park board permitting process was not permissive enough.[57]

Police abolition advocates viewed the Sheraton Midtown Hotel and park encampments as a step in establishing a "police-free" city.[73][6] Volunteers and residents at some encampments pledged not to call 9-1-1 or allow access to law enforcement to access sanctuary locations.[6] Some of the neighbors near the Powderhorn Park encampment, who were described in a profile by The New York Times as progressive and mostly White, also agreed to avoid calling the police.[74] Many campsites across the city, however, featured crime and safety challenges, such robberies, rapes, sex trafficking, assaults, drug overdoses, and shootings.[13] Some neighbors were conflicted about calling law enforcement to respond to violence at the camps, with some instances of reluctance reportedly out of fear that it might subject People of Color to further trauma.[74] Activists at Powderhorn Park encampment were criticized for not calling paramedics to treat people who overdosed on drugs, and some speculated that deaths or serious drug-related medical injuries could have been prevented had emergency services been rendered.[13] Activists also drew criticism for not assisting law enforcement investigations of crimes at encampment sites, such as the when people refused to identify the alleged perpetrator who raped a 14-year old at the Powderhorn Park camp.[13]

By July, some neighbors of park encampments expressed in media interviews the viewpoint that the all-volunteer at effort did work effectively.[49] It was also reported that at times many of the volunteer and resident-led meetings at encampments became contentious.[8] At encampments, some activists resisted outside help from social service providers and government agencies and insisted that they were self-sufficient,[13] and other volunteers felt that well-intentioned efforts were ultimately doing more harm to vulnerable people. Park Board Vice President LaTrisha Vetaw characterized some of the activists at encampments as "White saviors" who in her opinion were naïve to the social and economic needs of people at encampments.[13][71] After one of the two Powderhorn Park encampments closed in mid July, a statement by the Minnesota Sanctuary Movement said, "Powderhorn Sanctuary residents and volunteers have been at risk of violence not because of a failure of volunteers, but because of the lack of any coordinated response by our representatives and electeds (sic), a buildup of decades of absolute neglect in the area of dignified housing, and centuries of structural violence.…Sanctuary volunteers are helping residents move as best as they are able, but the park's new permitting system is not workable, the incompetent city has no solutions, and the county and state have not accepted responsibility."[49]

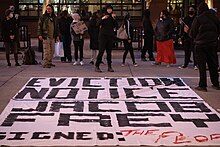

City officials adopted a de-escalation for disbanding camps due to the ongoing civil unrest, and when they attempted to remove tents at non-permitted sites, they faced opposition from the sanctuary movement and protest groups.[14] Park encampment closures, even after several health and safety incidents that drew concern from neighborhoods, were the subject of protests by non-resident activist who blocked officials from clearing camps.[14][62] Some protesters acted as "eviction defense" by boarding heavy machinery that cleared supplies and material from camps, resulting in officers firing pepper spray and making arrests.[71] On September 5, a protest group marched from Bryant Park to the home of Al Bangoura, the park board superintendent, to protest park board actions regarding camps. A protester breached the property, climbed onto the porch roof, and spray-painted security cameras to obstruct surveillance.[13] Hundreds of people protested the closure of the Powdernhorn Park camp on July 20 and about four or five people were arrested.[49] In August, protesters blocked officials from clearing the Peavy Park encampment, which was located adjacent to a school playground and had been the location of several violent incidents.[14]

About 100 protests gather outside the Minnesota State Capitol building in Saint Paul in September to demand that the governor and state legislature increase public support for hotel rooms for unhoused persons and greater investment in public housing.[71]

Aftermath

Permitted versus unpermitted sites

In 2020, the park board issued permits for five encampments, those at Lake Harriet (up to 11 tents), Marshall Terrace Park (up to 15 tents), The Mall (up to 15 tents), William Berry Park (up to 25 tents), and outside the Theodore Wirth House.[13][75] The park board designated 12 other parks as suitable locations for encampments: Annie Young Meadow, Beltrami Park, BF Nelson Park, Boom Island Park, Bryn Mawr Meadows Park, Franklin Steele Park, Lake Nokomis, Logan Park, Lyndale Farmstead Park, Minnehaha Park, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Park, and Riverside Park.[75]

The park board had difficulty controlling the number and size of camps despite the permitting process it established.[12] Encampments spread to 40 park sites by mid year.[16] The park board reported that there was a total of 44 encampment park sites throughout 2020, while a media source reported as many as 55 park encampments had appeared by August.[15][1]

According to the park board, the encampments brought an influx of people into Minneapolis who sought to live in city parks.[1] Some people in unpermitted encampments were offered help to move to other permitted camps, but many refused.[49] Several encampment residents declined available shelter space during the permit project.[2] Some encampment residents said they felt threatened by activists if they tried to leave encampments, while others said they were paid by activists to remain at encampments.[13]

Public services and costs

The park board spent $713,856 to administer camps from June 2020 to early January 2021, including use of $373,350 in Minnesota Emergency Response Funds.[2] The park board provided portable toilets, trash containers, and stations for handwashing at camp sites.[67] By aftermath of the encampment project, the park board had spent close to $1 millions on costs associated with encampments and lawsuits.[3] Some felt that the number of toilets and handwashing stations were too limited, which made it difficult to stop the spread of communicable diseases at camp sites.[21] The board and park staff collaborated with several agencies to help find available shelter beds, such as Minnesota Interagency Council on Homelessness, and Heading Home Hennepin.[2] By October 2020, officials for Hennepin County, the regional jurisdiction that included Minneapolis, had spent $12 million to provide housing for those at serious risk of COVID-19, and proposed a $22 million plan for six additional shelter sites for county residents experiencing homelessness.[4]

Health and safety issues

Worries about the spread of SARS-CoV-2 in shelters were cited by some encampment residents as their reason to say at park sites as opposed to shelter spaces or other housing options.[21] Despite creating a permit process for encampments, the park board said in July 2020 that "parks are not designed or operated in a manner that supports human habitation", and that they preferred to work with partner organizations to find housing options for those experiencing homelessness and residing in park encampments.[4][76] The park board did not view the encampments as a permanent or long-term solution, citing the onset of extreme winter weather brought on by Minneapolis' climate that could pose other health and safety challenges to residents living in encampments.[13] Officials considered the park encampments a short-term solution during a chaotic year that was necessary only until people could be connected with shelters and housing.[13]

Many encampments received notoriety for shootings, drug use, drug trafficking, sexual assaults, sex trafficking, and other safety concerns.[12][13][11][1][77] Neighbors who lived near park encampments said that regular gunshots were heard in the area of parks.[49] Parks that had encampment sites were left littered with trash, abandoned camping equipment, hypodermic needles, and human waste.[56] After several sexual assaults occurred at encampments, including of minors, volunteers had to move some women and children to secret, non-permitted campsites in other parts of the city.[49][52] By the end of the permit period, four people died had in Minneapolis park encampments, between the time of June 2020 and January 2021.[1] One of the park deaths was a homicide of the 38-year old Sedric Dorman of Minneapolis, who was fatally stabbed inside a tent at Minnehaha Park on January 3, 2021.[78][7] The Minneapolis Parks Police Department tallied 130 incidents of violent crimes such as homicide, rape, and aggravated assault in city parks during 2020 when encampments were permitted in parks, a 41.3% increase compared to the 10-year average of 92 such incidents.[79]

Permits not renewed for 2021

Park board commissioners passed a resolution by a 5-3 vote on February 3, 2021, to cancel encampment permits and defer to human services agencies and Hennepin County for the provision of services to unsheltered people living in parks.[2] Park Board President Jono Cowgill and Commissioners Bourn, Forney, Meyer, and Musich voted for the resolution. Commissioners Londel French, AK Hassan, and Kale Severson voted against it.[2] The board's resolution stated that use of encampments to shelter homeless people "is not a safe, proper, or dignified form of housing and is, at best, a temporary solution for encamped individuals", and it encouraged "the State of Minnesota, Hennepin County, and the City of Minneapolis to continue pursuit of expanded opportunities for permanent shelter for unsheltered homeless populations". The resolution revoked the authority of the park board superintendent to issue future encampment permits.[80] At the park board's February 3 meeting, a Minneapolis resident circulated a petition to disband the independent board in lieu of city government management of parks, and blamed the park board commissioner for the violence, sexual assaults, shootings, and homicides that occurred on parkland during 2020.[2]

November 2021 election

The prohibition of encampments on park property became a major topic of discussion for candidates seeking park board office in the November 2021 Minneapolis municipal election.[81][82] The encampments became a wedge issue that divided city residents and candidates with the November 2021 election a referendum on the park board's social agenda.[3][83] Incumbent Londel French blamed his failed reelection bid for an at-large board seat due to on his stance on maintaining the Hiawatha Golf Course and support for park encampments. Park board candidate Alicia Smith, who won an at large seat in the 2021 election, had volunteered at the Powdernhorn Park encampment. Smith opposed permitting encampments in the park system, but wanted to also treat unsheltered people with dignity and respect.[82]

See also

- 2020–2021 Minneapolis–Saint Paul racial unrest

- History of Minneapolis

- List of tent cities in the United States

- Neighborhoods of Minneapolis

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Minneapolis Park & Recreation Board (April 2021). "Superintendent's Annual Report 2020 Rising to Challenges During a Pandemic". www.minneapolisparks.org. Retrieved 2021-04-03.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Du, Susan (2021-02-05). "Minneapolis Park Board ends encampment permits, asks other agencies to take lead on homeless". Star Tribune.

- ^ a b c Du, Susan (2020-10-30). "Minneapolis Park Board election a referendum on expanding social agenda". Star Tribune. Retrieved 2020-10-30.

- ^ a b c d e Feshir, Riham (2020-10-19). "Lawsuit filed over displacement of homeless from Minneapolis parks". Minnesota Public Radio.

- ^ a b "Encampments". Minneapolis Park & Recreation Board. 2021-01-10. Archived from the original on 2020-07-02. Retrieved 2021-04-23.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Enzinna, Wes (2020-10-01). "The Sanctuary: Life in a cop-free zone". Harper's Magazine. October 2020.

- ^ a b c Walsh, Paul (2021-01-06). "Authorities ID man fatally stabbed at homeless encampment in Minnehaha Regional Park". Star Tribune. Retrieved 2021-04-23.

- ^ a b c d Schroven, Kay (2020-08-17). "Shrinking sanctuary encampment at Powderhorn Park?". Southside Pride.

- ^ a b Staff (2021-01-03). "Man's death at Minneapolis homeless encampment under investigation". Star Tribune. Retrieved 2021-01-03.

- ^ Otárola, Miguel (4 June 2020). "Volunteers turned former Sheraton Hotel in Minneapolis into sanctuary for homeless". Star Tribune.

- ^ a b c d e Otárola, Miguel (22 July 2020). "Minneapolis Park Board clears one of the Powderhorn homeless encampments". Star Tribune. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Sepic, Matt (2020-07-16). "Minneapolis Park Board approves smaller encampments". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved 2020-12-11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Rosengren, John (2020-12-13). "In a Tumultuous Year, COVID Puts Homeless Crisis Front and Center". MplsStPaul.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Otárola, Miguel (3 September 2020). "Encampment returns to Wall of Forgotten Natives, bringing call to action from Indigenous leaders". Star Tribune.

- ^ a b c d e f Gray, Callan (2020-08-06). "More encampments emerging in Minneapolis as Park Board pushes for action". KSTP. Retrieved 2020-08-06.

- ^ a b c Miguel Otárola, Miguel Otárola (2020-12-07). "Despite cold and Park Board pleas, homeless camps persist in three Minneapolis parks". Star Tribune. Retrieved 2020-12-11.

- ^ "Superintendent: Roles & Responsibilities". Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board. Archived from the original on 2015-03-18. Retrieved 2021-02-09.

- ^ Hazzard, Andrew (2020-01-06). "Jono Cowgill elected Park Board president". Southwest Journal. Archived from the original on 2021-02-10. Retrieved 2021-05-31.

- ^ "About the Board". Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board. Retrieved 2021-02-09.

- ^ "ParkScore". parkscore.tpl.org. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Nesterak, Max (2020-06-16). "Minneapolis Police shut down former hotel-turned-homeless sanctuary". Minnesota Reformer. Retrieved 2021-02-08.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Brey, Jared (2020-06-23). "The Story Behind the Minneapolis 'Sanctuary Hotel'". Next City. Archived from the original on 2020-06-24. Retrieved 2021-05-14.

- ^ a b c Wieffering, Helen; Aning, Agya K.; Wegner, Helena (2020-12-14). "Federal aid divides homeless in the Twin Cities". Howard Center for Investigative Journalism.

- ^ "Emergency Executive Order 20-04: Providing for Temporary Closure of Bars, Restaurants, and Other Places of Public Accommodation" (PDF). Minnesota Legislative Reference Library. 2020-03-16. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-03-20.

- ^ State of Minnesota. "Emergency Executive Order 20-20" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-03-28.

- ^ State of Minnesota. "Emergency Executive Order 20-18" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-03-25.

- ^ State of Minnesota. "Emergency Executive Order 20-19" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-03-25.

- ^ State of Minnesota (2020-03-23). "Emergency Executive Order 20-14: Suspending Evictions and Writs of Recovery During the COVID-19 Peacetime Emergency" (PDF). Minnesota Legislative Reference Library. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-10-19.

- ^ State of Minnesota (2020-05-13). "Emergency Executive Order 20-55: Protecting the Rights and Health of At-Risk Populations during the COVID19 Peacetime" (PDF). Minnesota Legislative Reference Library. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-09-22.

- ^ Hennessey, Kathleen; LeBlanc, Steve (June 4, 2020). "8:46: A number becomes a potent symbol of police brutality". Associated Press. Archived from the original on June 9, 2020. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- ^ Carrega, Christina; Lloyd, Whitney (June 3, 2020). "Charges against former Minneapolis police officers involved in George Floyd's death". ABC News. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- ^ Navarrette, Ruben Jr. "Haunting question after George Floyd killing: Should good cops have stopped a bad cop?". USA Today.

- ^ a b Stockman, Farah (2020-07-03). "'They Have Lost Control': Why Minneapolis Burned". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-02-06.

- ^ Caputo, Angela, Craft, Will and Gilbert, Curtis (30 June 2020). "'The precinct is on fire': What happened at Minneapolis' 3rd Precinct — and what it means". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved on 1 July 2020.

- ^ Moini, Nina (14 August 2020). "St. Paul rebuilding efforts inch along after civil unrest". Minnesota Public Radio.

- ^ Meitrodt, Jeffrey (13 August 2020). "Landscape of rubble persists as Minneapolis demands taxes in exchange for permits". Star Tribune. Retrieved on 13 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Serres, Chris; Otárola, Miguel (2020-05-09). "As Minneapolis homeless camp raises health alarms, officials move to contain its spread". Star Tribune.

- ^ a b c d Staff (2020-05-08). "Amid virus fears, Minneapolis homeless encampment grows". Associated Press. Retrieved 2021-01-02.

- ^ "Curfew to go into effect for Minneapolis-St. Paul starting at 8 p.m. on Friday". KTTC. May 29, 2020. Archived from the original on June 3, 2020. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- ^ Bosley, Lindsay (30 May 2020). "Frequently asked questions about the curfew in Minneapolis". City of Minneapolis: News. Retrieved on July 2, 2020.

- ^ Walsh, Paul (28 July 2020). "ACLU sues law enforcement leaders over wounding of protesters in Minneapolis". Star Tribune.

- ^ Pross, Katrina (5 June 2020). "Nightly curfews in Minneapolis, St. Paul to end". Pioneer Press. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Nesterak, Matt (2020-06-09). "Hotel owner wants to evict, some residents plan to stay at homeless sanctuary". Minnesota Reformer. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

- ^ Staff (2020-06-03). "Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board unanimously votes to sever ties with Minneapolis Police Department". KSTP. Archived from the original on 2020-06-04. Retrieved 2020-06-07.

- ^ a b c Serres, Chris (13 June 2020). "'Nowhere left to go': Minneapolis homeless forced out of a hotel face uncertain future". Star Tribune.

- ^ a b c Haavik, Emily and Wigdahl, Heidi (7 July 2020). "Police investigating 3 sexual assaults at Powderhorn Park encampment". KARE-11. Retrieved on 7 July 2020.

- ^ a b "Powderhorn Park". Minneapolis Park & Recreation Board. 2021. Archived from the original on 2016-05-09. Retrieved 2021-05-11.

- ^ Sepic, Matt (2020-06-19). "Divided Minneapolis Park Board supports encampment at Powderhorn Park". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Tilsen, David (2020-07-27). "Sanctuary denied". South Side Pride. Retrieved 2020-07-27.

- ^ a b c d Staff (2020-07-16). "2 shot, wounded at homeless encampment in Peavey Field Park". Star Tribune.

- ^ Staff (2020-06-27). "Minneapolis Park Police: Juvenile sexually assaulted at Powderhorn Park". FOX-9.

- ^ a b c Johnson, Allie (2020-07-07). "Juvenile sexually assaulted at Powderhorn Park encampment, 3rd sexual assault reported in last 3 weeks". FOX-9.

- ^ State of Minnesota (2020-05-13). "Emergency Executive Order 20-55: Protecting the Rights and Health of At-Risk Populations during the COVID19 Peacetime" (PDF). Minnesota Legislative Reference Library. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-09-22.

- ^ "Emergency Executive Order 20-79; Rescinding Emergency Executive Orders 20-14 and 20-73: Modifying the Suspension of Evictions and Writs of Recovery During the COVID-19 Peacetime Emergency" (PDF). Minnesota Legislative Reference Library. 2020-07-14. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-09-25.

- ^ a b Sepic, Matt (2020-06-16). "Minneapolis Park Board approves scaling back of large encampments". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved 2020-06-16.

- ^ a b c d e f Thiede, Dana (2020-09-24). "Peavey Park encampment cleared out". KARE-11. Retrieved 2020-09-25.

- ^ a b c Hazzard, Andrew (2020-08-05). "City's first park permit issued to Lake Harriet encampment". Southwest Journal. Archived from the original on 2020-08-17. Retrieved 2020-08-06.

- ^ a b c Jany, Libor (2020-07-30). "Minneapolis officials clear second large homeless camp". Star Tribune. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

- ^ Harlow, Tim (2020-08-14). "Minneapolis officials clear Powderhorn Park of last campers". Star Tribune.

- ^ Editorial Board (2020-08-14). "Tent camps put homeless, others at risk". Star Tribune. Retrieved 2020-08-14.

- ^ Staff (2020-08-12). "MPRB Shuts Down 3 Unauthorized Minneapolis Park Encampments". WCCO.

- ^ a b c Staff (2020-09-24). "Demonstrators Gather In Downtown Minneapolis To Protest Homeless Encampment Eviction". WCCO. Retrieved 2020-09-25.

- ^ Staff (2020-07-01). "Teen shot several times near encampment at Peavey Park in Minneapolis, reports say". Star Tribune.

- ^ Staff (2020-08-12). "MPRB Shuts Down 3 Unauthorized Minneapolis Park Encampments".

- ^ Serres, Chris (2018-11-18). "Fourth person dies at Minneapolis homeless camp". Star Tribune.

- ^ Gottfried, Mara (2020-10-29). "Judge: No legal basis to immediately halt sweeps of Minneapolis homeless encampments". Pioneer Press. Retrieved 2021-05-05.

- ^ a b c "Encampments". Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board. Archived from the original on 2020-07-02. Retrieved 2021-02-11.

- ^ a b Mohs, Marielle (2020-01-02). "Minneapolis Park Board: Minnehaha Park Encampment Residents Must Vacate By Sunday". WCCO. Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- ^ "Minnehaha Regional Park". Minneapolis Park & Recreation Board. 2021. Archived from the original on 2016-03-21. Retrieved 2021-05-11.

- ^ Staff (2021-01-03). "Man's death at Minneapolis homeless encampment under investigation". Star Tribune. Retrieved 2021-01-03.

- ^ a b c d Otárola, Miguel (2020-09-21). "Months after uprising, Minneapolis Sanctuary Movement raises alarm over homeless crisis". Star Tribune. Retrieved 2020-09-22.

- ^ "About". Minneapolis Sanctuary Movement. Archived from the original on 2021-05-27. Retrieved 2021-05-27.

- ^ Brown, Alleen; Hvistendahl, Mara (2020-06-12). "Organizers in Minneapolis Weigh Role of Community Defense Groups in a Police-Free Future". The Intercept. Retrieved 2020-06-13.

- ^ a b Dickerson, Caitlin (2020-06-24). "A Minneapolis Neighborhood Vowed to Check Its Privilege. It's Already Being Tested". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-05-29.

- ^ a b Minneapolis Park & Recreation Board (2020-08-07). "Update on temporary encampments: Minneapolis park staff name 16 parks as permitted or capable of accommodating temporary encampments". minneapolisparks.org. Retrieved 2020-08-07.

- ^ Bangoura, Al (2020-07-01). "Update: Refuge Space to People Currently Experiencing Homelessness" (PDF). Minneapolis Park & Recreation Board. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-07-16. Retrieved 2020-07-01.

- ^ Walsh, Paul (2020-07-08). "Tent encampment a powder keg as crime grips Powderhorn Park". Star Tribune. Retrieved 2020-07-08.

- ^ Staff (2021-01-03). "Man's death at Minneapolis homeless encampment under investigation". Star Tribune. Retrieved 2021-01-03.

- ^ Du, Susan (2022-07-28). "Violent crimes in Minneapolis park hot spots down drastically in 2022". Star Tribune. Retrieved 2022-07-28.

- ^ Manier, Miranda (2021-02-05). "Minneapolis Park Board ends homeless encampment permits". KARE-11.

- ^ "A guide to the 2021 Minneapolis Park Board and Board of Estimate & Taxation candidates: See views on homeless encampments, debt and more". Star Tribune. 2021-10-01. Retrieved 2021-10-01.

- ^ a b Hazard, Andrew (2021-11-10). "There are plenty of new faces on the Minneapolis Park Board, but just one person of color". Sahan Journal. Retrieved 2021-11-10.

- ^ Halter, Nick (2021-08-19). "Encampments become wedge issue in Minneapolis Park Board races". Axios. Retrieved 2021-08-19.

Further reading

- Tamburino, Joseph (June 30, 2021). "Allowing homeless camps in Minneapolis parks is terrible policy". Star Tribune.

- Cohen, Rachel (July 15, 2020). "How the Largest Known Homeless Encampment in Minneapolis History Came to Be". The Appeal.

- Chuculate, Eddie (October 6, 2020). "Activist wants to prevent Wall of Forgotten Natives". The Circle.

- Lurie, Julia (June 12, 2020). "They Built a Utopian Sanctuary in a Minneapolis Hotel. Then They Got Evicted. The short life and sudden death of the Share-a-Ton". Mother Jones.

- Kozlowski, James C. (January 21, 2021). "Law review: Sweeps' of Homeless Encampments in Parks During COVID-19". National Recreation and Park Association Magazine (February 2021).

- Ostfield, Gili (October 30, 2020). "Ten Moves, Two Tents, and Five Months of a Housing Reckoning in Minneapolis". The New Republic.

- Silvia, Daniella and Ed Ou (October 9, 2020). "Homeless and facing winter in Minneapolis: Racial inequality, skyrocketing housing prices and stagnating wages have created a dire problem here and across the nation. NBC News.

External links

- Berry v. Hennepin County, Case No. 20-cv-2189 (WMW/LIB) (D. Minn. Oct. 29, 2020)

- Hennepin County - Coordinated Entry homeless assistance

- Metropolitan Urban Indian Directors - Franklin/Hiawatha Encampment: Wall of Forgotten Natives Archived 2021-06-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board, Resolution 2020-267