Ethnic groups in the Caucasus

The peoples of the Caucasus, or Caucasians, are a diverse group comprising more than 50 ethnic groups throughout the Caucasus.[2]

By language group

Language families indigenous to the Caucasus

Caucasians who speak languages which have long been indigenous to the region are generally classified into three groups: Kartvelian peoples, Northeast Caucasian peoples and Northwest Caucasian peoples.

The largest peoples speaking languages which belong to the Caucasian language families and who are currently resident in the Caucasus are the Georgians (3,200,000), the Chechens (2,000,000), the Avars (1,200,000), the Lezgins (about 1,000,000) and the Kabardians (600,000), while outside the Caucasus, the largest people of Caucasian origin, in diaspora in more than 40 countries (such as Jordan, Turkey, the countries of Europe, Syria, and the United States) are the Circassians with about 3,000,000-5,000,000 speakers. Georgians are the only Caucasian people who have their own undisputedly independent state—Georgia. Abkhazia's status is disputed. Other Caucasian peoples have republics within Russia: Adyghe (Adygea), Cherkess (Karachay-Cherkessia), Kabardians (Kabardino-Balkaria), Ingush (Ingushetia), Chechens (Chechnya), while other Northeast Caucasian peoples mostly live in Dagestan.

Indo-European

Caucasians that speak languages belonging to the Indo-European language family:

- Armenians

- Germans

- Latins†, including Roman Latin Italian-Greeks Latin Europeans/European Latin Americans

- Hellenic group:

- Caucasus Greeks, including Turkish-speaking Christian Greeks of Georgia or Urums

- Pontic Greeks

- Iranian group:

- Loms

- Slavic group:

- Russians, including Cossacks and Spiritual Christians

†Although the group does not have any inhabitants physically living anywhere in the Caucasus, genetic tests have proven their affinity to Caucasian populations and shown that their ancestors originated from the Caucasus.

Armenians number 3,215,800 in their native Armenia, though approximately 8 million live outside the republic, forming the Armenian diaspora. Elsewhere in the region, they reside in Artsakh (which is a de facto independent republic, though not recognised internationally), Georgia (primarily Samtskhe–Javakheti, Tbilisi, and Abkhazia), and the Russian North Caucasus. The Ossetians live in North Ossetia–Alania (an autonomous republic within Russia) and in South Ossetia, which is de facto independent, but is de jure part of Georgia. The Yazidis reside in the western areas of Armenia, mostly in the Aragatsotn marz, and in the eastern areas of Georgia. An autonomous Kurdish region was created in 1923 in Soviet Azerbaijan but was later abolished in 1929. Pontic Greeks reside in Armenia (Lori Province, especially in Alaverdi) and Georgia (Kvemo Kartli, Adjara, the Tsalka, and Abkhazia). Pontic Greeks had also made up a significant component of the South Caucasus region acquired from the Ottoman Empire (following the 1878 Treaty of San Stefano) that centred on the town of Kars (ceded back to Turkey in 1916). Russians mostly live in the Russian North Caucasus and their largest concentration is in Stavropol Krai, Krasnodar Krai, and Adygea. Georgia and the former Russian South Caucasus province of Kars Oblast was also home to a significant minority of ethnic (Swabian) Germans, although their numbers have become depleted as a result of deportations (to Kazakhstan following World War II), immigration to Germany, and assimilation into indigenous communities.

Semitic

Caucasians that speak languages belonging to the Semitic language family:

- Assyrians in the Caucasus number approximately 35,000 people, and live in Armenia, Georgia,[3] Azerbaijan and southern Russia. There are up to 15,000 in Georgia,[3] 5000 in Armenia, up to 15,000 in southern Russian regions of the Caucasus and 1400 in Azerbaijan. They descend from the ancient Mesopotamians and are indigenous to what is today Iraq, Northeastern Syria, Northwestern Iran, and Southeastern Turkey. They are Eastern Rite Christians, mainly followers of the Assyrian Church of the East, and speak and write Mesopotamian Eastern Aramaic dialects.

- Caucasus Jews of two sub-ethnic groups Mountain Jews and Georgian Jews. There are about 15,000–30,000 Caucasus Jews (as 140,000 immigrated to Israel, and 40,000 to the US).

- Arabs in the Caucasus: a population of nomadic Arabs was reported in 1728 as having rented winter pastures near the Caspian shores of the Mugan plain (in present-day Azerbaijan). In 1888, an unknown number of Arabs still lived in the Baku Governorate of the Russian Empire. As well as descendants of Sayyid and Siddiqui – the people with Arabian origin, but mostly assimilated by other Caucasian peoples. However, some people identify not just as Sayyid or Siddiqui with non-Arabian ethnicity, but as Arabs.[4][5]

Mongolic

The Kalmyks is the name given to the Oirats, western Mongols in Russia, whose ancestors migrated from Dzungaria in 1607. Today they form a majority in the autonomous republic of Kalmykia on the western shore of the Caspian Sea. Kalmykia has Europe's only Buddhist government.[6]

Turkic

Caucasians that speak languages belonging to the Turkic language family:

The largest of the Turkic-speaking peoples in the Caucasus are Azerbaijanis who number 8,700,000 in the Republic of Azerbaijan. In the Caucasus region, they live in Georgia, Russia (Dagestan), Turkey and previously in Armenia (before 1990). The total number of Azerbaijanis is around 35 million (15 million in Iran). Other Turkic speakers live in their autonomous republics within Russia: Karachays (Karachay-Cherkessia), Balkars (Kabardino-Balkaria), while Kumyks and Nogais live in Dagestan.

By location

This gives ethnic locations about 1775 before the Russians came.[7] NECLS means 'Northeast Caucasian Language Speakers' and NWCLS means 'Northwest Caucasian Language Speakers'. The linguistic nationalities that we now recognise are somewhat artificial. Two hundred years, ago a person's loyalty was to their friends, kin, village and chief and not primarily to their language group. The difference between steppe, mountain and plain was far more important than difference of language. Only the southern half (and the southernmost part of Dagestan) had organized states, usually Persian or Turkish vassals and few, if any, of these states corresponded well to language groups.

Northern Lowlands: The Turkic-speaking Nogai nomads occupied almost all of the steppe north of the Caucasus. In the nineteenth century they were pushed far southeast to their present location. Formerly part of the eastern steppe was occupied by Kalmyks – Buddhist Mongols who migrated from Dzungaria about 1618. In 1771 many returned to their original homeland and they contracted to their present location in the far northeast, Nogais temporarily taking their place. In the southeast were the isolated Terek Cossacks. Their settlements later grew into the North Caucasus Line. There were a few Turkmens in the center of the steppe.

North Slope: The western two thirds was occupied by Circassians – NWCLS divided into twelve or so tribes. They long resisted the Russians and in 1864 several hundred thousand of them were expelled to the Ottoman Empire. To their east were the Kabardians – NWCLS similar to the Circassians but with a different political organization. The term Lesser Kabardia refers to the eastern area. South of the eastern Circassian-Kabardians were three groups that seem to have been driven into the high mountains about 500 years previously. The Karachays and Balkars spoke similar Turkic languages. East of the Balkars were the Ossetians – Iranian speakers descended from the ancient Alans who controlled the future Georgian Military Road and had a growing Christian minority. East of the future highway was a north-south band of Ingush – NECLS similar to the Chechens. The numerous Chechens to the east were later to wage the long Murid War against the Russians. For the small groups south of the Ingush-Chechens see South Slope below. To the east along the coast were the Turkic Kumyks.

Mountain Dagestan: All the peoples of mountain Dagestan were NECLS except the Tats. In the northwest were a number of small language groups (Tsez people (Dido) and Andi people), similar to the Avars. To their southeast were the numerous Avars with a khanate at Khunzakh who fought in the Murid War. Southeast were the Dargins and west of them the Laks who held the Kumukh Khanate. Southeast along the Samur were the Lezgins with many subgroups and then the Iranian-speaking Tats down to Baku.

Caspian Coast: From Astrakhan to the Terek River there were the Buddhist Kalmyk nomads. Along the Terek were the isolated Terek Cossacks. From the Terek to Derbent were the Turkic-speaking Kumyks with a state at Tarki. The town of Derbent itself had a majority Persian (Template:Lang-ru) population, as it had for many centuries, until the late 19th century.[8] On the coastal plain south of Derbent was a mixed population, mostly Azeri ("Transcaucasian Tatar"), and further south to Baku were the Iranian-speaking Tats. When Baku became a boom town the Tats retained a majority only in the mountains. The Mountain Jews, who had a number of villages inland from the coast, spoke a form of Tat called Judeo-Tat. The lowlands south of Baku were held by Azerbaijanis, Turkic-speaking Shiites. On both sides of the current Iranian border were the Iranian-speaking Talysh. Based on genetic studies the Gilaki and Mazanderani ethnic groups in northern Iran (near the Caspian Sea) have been proven to be genetically similar to Armenians, Georgians and Azeris. This indicates that the Gilaki and Mazanderani ethnic groups are people that immigrated from the Caucasus region to what is now northern Iran.[9]

South Slope: Black Sea coast: In the northwest the mountains came down to the sea and the population was Circassian. Southward the coastal plain broadened and the population was Abkhazians – similar to the Circassians but under Georgian influence.

South Slope proper: On the south side of the Caucasus the mountains fall quickly to the plains and there is only a small transition zone. The inhabitants were either Georgians with mountain customs or northern mountaineers who had moved south. The Svans were Georgian mountaineers. In the center the Iranian Ossets had moved south and were surrounded on three sides by Georgians. East of the Ossets and south of the Ingush-Chechens were three groups of Georgian mountaineers on both sides of the mountain crest: Khevi, Khevsurs, and Tushetians. The Bats were NECLS entangled with the Tushetians and the Kists were Chechens south of the mountains. Near the Georgian-Azeri linguistic border there were some Avars and Tsakhurs (Lezgians) who had crossed the mountains. Associated with the Tsakhurs were the Ingiloy or Georgian-speaking Muslims. In the north Azeri area were a few Udis or southern Lezgians and Lakhij or southern Tats.

Southern Lowlands: The western two thirds were occupied by Georgians – an ancient Christian people with a unique language. The eastern third was Azerbaijanis – a group of Turkic-speaking Shiites under Persian influence. On the fringe of the Georgian area were Georgian speakers who had either adopted Islam or mountain customs.

Armenian Highlands: Further South, the land becomes higher. In the west were the Laz people or Georgian Muslims. In Kars province there were Turks, Kurds and Armenians. The Armenians, which gave the plateau its namesake, were somewhat concentrated in the present-day Armenia but were mostly spread out as a minority all over Asia Minor. There were groups of Azeris west of their main area who tended to blend with the Turks. The Kurds were semi-nomadic shepherds with small groups in various places and concentrations in Kars province and Nakhchivan. In the far southeast were the Iranian Talysh.

Genetic history

Language groups in the Caucasus are closely correlated to genetic ancestry.[10]

Gallery

-

Armenian from Shusha, Nagorno-Karabakh, early 20th century

-

Young Azerbaijani from Shusha

-

Chechen warrior, 19th century

-

Chechen family from 1920

-

Circassian warrior

-

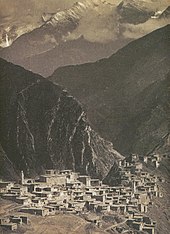

Dagestani (1904)

-

Khevsur clansmen in Georgia, c. 1910

-

Kuban Cossacks, 1915

-

A raid by Kurds

-

Group of Lezgin men, 1880

-

Mingrelians, 1865

-

Mountain Jews, c. 1898

-

Ossetian warrior

-

Russian settlers in Azerbaijan, c. 1910

-

Groom wearing a chokha at a Tushetian wedding

-

Mullahs at the Mosque near Batumi, c. 1910

See also

Further reading

- "The morphological specificity of Caucasian peoples according to craniological materials". V.P.Alekseev. Journal of Human Evolution.

- Kovalevskaia, V. B "Central Ciscaucasia in Antiquity and Early Middle Ages: Caucasian Substratum and Migrations of the Iranic-Speaking Tribes." (1988).

References

- ^ "ECMI - European Centre For Minority Issues Georgia". Ecmicaucasus.org. Archived from the original on 4 September 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ "Caucasian peoples". Britannica.com. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ a b "The Yezidi Kurds and Assyrians of Georgia : The Problem of Diasporas and Integration into Contemporary Society" (PDF). Aina.org. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ "Персонажи традиционных религиозных представлений азербайджанцев Табасарана". Tabasaran.com. Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ Stephen Adolphe Wurm et al. Atlas of languages of intercultural communication. Walter de Gruyter, 1996; p. 966

- ^ "Europe - Peace and Harmony in Kalmykia". Buddhistchannel.tv. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ Arthur Tsutsiev and Nora Seligman Favorov (translator) Atlas of the Ethno-Political History of the Caucasus, 2014, Map 4 supplemented by Maps 12,18 and 31.

- ^ "население дагестана". Ethno-kavkaz.narod.ru. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ Nasidze, Ivan; Quinque, Dominique; Rahmani, Manijeh; Alemohamad, Seyed Ali; Stoneking, Mark (April 2006). "Concomitant Replacement of Language and mtDNA in South Caspian Populations of Iran". Curr. Biol. 16 (7): 668–73. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.02.021. PMID 16581511. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- ^ O.Balanovsky et al., "Parallel Evolution of Genes and Languages in the Caucasus Region", Mol Biol Evol00 (2011), doi:10.1093/molbev/msr126.

- ^ Sevruguin, Antoin. "An Armenian girl from New Julfa, Isfahan, Late 19th Century". The Nelson Collection of Qajar Photography.

- ^ "Orden F. Azerbaijani woman from Baku in national costume, circa 1890s". Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography.

![An Armenian girl from New Julfa, Isfahan, or Azerbaijani woman from Baku, late 19th century[11][12]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f1/Azerbaijani_woman_from_Baku_in_national_costume%2C_circa_1890s.jpg/83px-Azerbaijani_woman_from_Baku_in_national_costume%2C_circa_1890s.jpg)