Charles Hotham

Sir Charles Hotham | |

|---|---|

Lithograph by James Henry Lynch, printed by Day & Son, 1859 | |

| 2nd Lieutenant-Governor of Victoria | |

| In office 22 June 1854 – 22 May 1855 | |

| Preceded by | Charles La Trobe |

| 1st Governor of Victoria | |

| In office 22 May 1855 – 10 November 1855 | |

| Monarch | Queen Victoria |

| Succeeded by | Sir Henry Barkly |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 14 January 1806 Dennington, Suffolk, England |

| Died | 31 December 1855 (aged 49) Melbourne, Victoria |

| Nationality | British subject |

| Spouse | Jane Sarah Bridport |

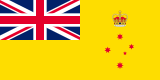

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Eureka Rebellion |

|---|

|

|

|

Captain Sir Charles Hotham KCB (14 January 1806 – 31 December 1855)[1] was Lieutenant-Governor and, later, Governor of Victoria, Australia from 22 June 1854 to 10 November 1855.

Early life

Hotham was born at Dennington, Suffolk, England. His father was Rev. Frederick Hotham, prebendary of Rochester, and his mother was Anne Elizabeth née Hodges.[1] Hotham entered the navy on 6 November 1818,[1] and had a distinguished career. He was in command of the steam sloop HMS Gorgon which ran aground in Montevideo Bay in May 1844 and showed skill and determination in getting her refloated by November.[2]

One of the lieutenants on board was the future Admiral Sir Astley Cooper Key.[3] Hotham's last active service was as a commodore on the coast of Africa in 1846 on HMS Devastation. In 1846 he was knighted. In April 1852 he was appointed minister plenipotentiary on a mission to some of the South American republics.

Australia

Hotham was appointed lieutenant-governor of Victoria on 6 December 1853 by the Duke of Newcastle.[1] Later, Hotham was made captain general and governor-in-chief. He was received with great enthusiasm when he landed at Melbourne on 22 June 1854, and there appeared to be every prospect of his being a popular governor. Hotham found that the finances of the colony were in great disorder, there was a prospective deficiency of over £1,000,000, and a bad system had grown up of advances being made to the various departments under the title of "imprests".

Hotham wisely appointed a committee of two bankers and the auditor-general to inquire into the position, and this committee promptly advised the abolition of the "imprest" system. It was eventually found that under this system a sum of £280,000 could not be accounted for. His efforts at retrenchment brought Hotham much unpopularity, but on questions of finance he was always sound and great improvements in this regard were made during his short term of office.

Hotham was governor at the time of the Eureka Stockade. When Hotham became lieutenant-governor, replacing La Trobe, he enforced mining licensing laws. On 19 November 1854, he appointed a Royal Commission on goldfields problems and grievances. According to historian Geoffrey Blainey "It was perhaps the most generous concession offered by a governor to a major opponent in the history of Australia up to that time. The members of the commission were appointed before Eureka...they were men who were likely to be sympathetic to the diggers."

Hotham was a naval officer who had been used to strict discipline, and though he eventually realised that the arrogance of the officials who were administering the law was largely responsible for the trouble, when, on 25 November 1854, a deputation waited on him to demand the release of some diggers who had been arrested, he took the firm stand that a properly worded memorial would receive consideration, but none could be given to "demands".

The rebellion which broke out at the Eureka stockade on 3 December 1854 was quickly subdued, but the rebels arrested were all eventually acquitted. It was a time of great excitement in Melbourne, and the governor was convinced that designing men were behind the movement who hoped to bring about a state of anarchy. In these circumstances he felt that the only way of dealing with the trouble was the use of the strong hand.

The first eye witness account[4] of the Massacre at the Eureka Stockade in December 1854 was published just a year after the event, by Raffaello Carboni. He was a principal Rebel, multilingual and better educated than most. He was in no doubt that the man most responsible for the massacre was Lieutenant-Governor Charles Hotham.

On 30 November 1854, Carboni, Father Smyth and George Black (newspaper editor), from the Central Council of the Eureka Rebels, asked Ballarat Goldfields Commissioner Rede to call off the licence hunts which had intensified on Hotham's secret orders and which were enraging miners. Rede said that 'the licence is a mere cloak to cover a democratic revolution'. Carboni wrote that Rede was 'only a marionette … before us. Each of his words, each of his movements, was the vibration of the telegraph wires directed from Toorak' (p. xiii). H. V. Evatt, an esteemed legal mind of mid 20th century puts the blame for the massacre on Hotham's deliberate duplicity (p.xvi).

Carboni left the Stockade about midnight. He wrote that at that stage there was confidence about a resolution of the matter without bloodshed, but that was only because Hotham had told the miners and police and military, different things. No one was expecting an assault from the military and police Camp. He also wrote 'It was perfectly understood, and openly declared … that we meant to organise for defence, and that we had taken up arms for no other purpose'. (p. 67). And 'the spies being sent from the Camp to enrol themselves amongst the insurgents, and who, report says, urged them to attack the Camp, which was repudiated by the diggers - they saying they would act upon the defensive'. (p. 132).

Carboni, with 18 others, was put on trial for his life. Hotham directed that American Rebels, some of whom were very prominent, not be prosecuted. He gave them an amnesty; but not quite all, the African American John Joseph was abandoned by Hotham and American officials. The prisoners appealed to Hotham, 'There is a paragraph in our petition to the effect, that if 'His Excellency had found sufficient extenuation in the conduct of American citizens', we thought there were equally good grounds for extending similar clemency to all, irrespective of nationality …. it is a violation of the very principle enunciated by His Excellency in his report, viz.'That it is the duty of a Government to administer equal justice to all' (p. 134). There was a Royal Commission into the Massacre and Hotham wasn't blamed, probably because Hotham's critics were not heard. Hotham's post was raised to a full governorship on 3 February 1855.

While Hotham relied on his legal advisers in all constitutional questions, his position was one of great difficulty.

Constitutional government had been granted but not really effected, and it was not until 28 November 1855 that the first government under William Haines was formed. In 1855, Hotham had been endeavouring to carry out the views of his finance committee, and was receiving much criticism from a section of the press.

He was insistent that tenders for all works should be called through the Government Gazette, but not receiving support from the legislature, he ordered the stoppage of all constructional works. For some of his actions he was reprimanded by Sir William Molesworth, the secretary of state. Hotham then sent in his resignation in November 1855, and in doing so, mentioned that his health had materially suffered.

Later life

Hotham was conscientious, but he had little experience to help him in dealing with the exceptionally difficult problems of his period of governorship. He has been severely criticized, but his work on the finances of the colony was of great value.

Hotham, whose health was failing, caught a chill on 17 December 1855 while opening the Melbourne Gasworks. He died two weeks later on 31 December,[1] and was buried in the Melbourne General Cemetery.

In December 1853, he had married Jane Sarah, daughter of Samuel Hood Lord Bridport. She survived him.

Legacy

Several places have been named after him, most notably:

- Mount Hotham

- the town of Hotham (now North Melbourne)

- the federal Division of Hotham

- the Sir Charles Hotham Hotels in Melbourne and Geelong

- roads including Hotham Streets in Preston, Collingwood, East Melbourne, Traralgon, Cranbourne, Hughesdale, Lake Wendouree, Lower Templestowe and Seddon; Hotham Road, Niddrie; and Hotham Avenue in Mount Macedon.

See also

- O'Byrne, William Richard (1849). . . John Murray – via Wikisource.

References

- ^ a b c d e B. A. Knox, 'Hotham, Sir Charles (1806–1855)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 4, MUP, 1972, pp 429-430.

- ^ Key, Sir Astley Cooper (1847). A Narrative of the Recovery of the HMS Gorgon. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 113.

- ^ Key, Sir Astley Cooper (1847). A Narrative of the Recovery of the HMS Gorgon. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 113.

- ^ Carboni, Raffaello (1993). The Eureka Stockade with an introduction by Tom Keneally. Melbourne University Press. ISBN 0-522-83945-2.

- Governors of Victoria (Australia)

- 1806 births

- 1855 deaths

- Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

- Royal Navy officers

- People from Framlingham

- People from the Colony of Victoria

- Lieutenant-Governors of Victoria

- 19th-century Australian public servants

- Officers of the West Africa Squadron

- Burials at Melbourne General Cemetery

- People of the Eureka Rebellion

- Royal Navy captains