Bristol Harbour

Bristol Harbour is the harbour in the city of Bristol, England. The harbour covers an area of 70 acres (0.28 km2). It has existed since the 13th century but was developed into its current form in the early 19th century by installing lock gates on a tidal stretch of the River Avon in the centre of the city and providing a tidal by-pass for the river. It is called a Floating Harbour as the water level remains constant and it is not affected by the state of the tide on the river.

Netham Lock in east Bristol is the upstream limit of the harbour. Beyond the lock is a junction: on one arm the navigable River Avon continues upstream to Bath, and on the other arm is the tidal River Avon. The first 1 mile (1.6 km) of the floating harbour, downstream from Netham Lock, is an artificial channel known as the feeder canal, while the tidal River Avon follows its original route. Between Bristol Temple Meads railway station and Hotwells, the harbour and the River Avon run parallel at a distance of no more than 0.65 miles (1.0 km) apart. At Bristol Temple Meads railway station, the floating harbour occupies the original bed of the River Avon and meanders through Bristol city centre, Canon's Marsh and Hotwells. To the south, the tidal River Avon flows through an artificial channel known as the "New Cut". This separation of the floating harbour and the tidal River Avon reduces currents and silting in the harbour and prevents flooding. At Hotwells, the floating harbour rejoins the tidal River Avon via a series of locks and flows into the Avon Gorge.

The harbour today

Bristol Harbour was the original Port of Bristol, but as ships and their cargo have increased in size, it has now largely been replaced by docks at Avonmouth and Portbury. These are located 3 miles (5 km) downstream at the mouth of the River Avon.

The harbour is now a tourist attraction with museums, galleries, exhibitions, bars and nightclubs. Former workshops and warehouses have now largely been converted or replaced by cultural venues, such as the Arnolfini art gallery, Watershed media and arts centre, Bristol Industrial Museum and the At-Bristol science exhibition centre, as well as a number of fashionable apartment buildings. Museum boats are permanently berthed in the harbour. These include Isambard Kingdom Brunel's SS Great Britain, which was the first iron-hulled and propeller driven ocean liner.[1], and a replica of the Matthew in which John Cabot sailed to North America in 1497. The historic vessels of the Industrial Museum, which include the steam tug Mayflower, firefloat Pyronaut and motor tug John King, are periodically operated.

The Bristol Ferry Boat operates at the harbour, serving landing stages close to most of the harbour-side attractions and also providing a commuter service to and from the city centre and Bristol Temple Meads railway station. Two other independent ferry companies, Boatsatbristol.com and Number Seven Boat Trips, offer similar services. The Bristol Packet boats offer regular harbour tours with commentaries and also river cruises up the River Avon to Conham, Hanham and Bath and downstream to Avonmouth. In late July each year, the Bristol Harbour Festival is held, resulting in an influx of boats, including tall ships, Royal Navy vessels and lifeboats.

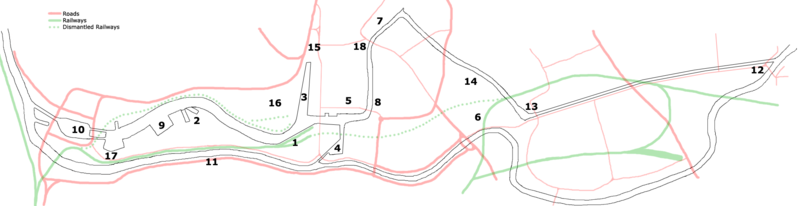

Sections, quays & harbourside features

- Prince's Wharf, including the Bristol Harbour Railway and Industrial Museum, Pyronaut

- Dry docks, SS Great Britain, The Matthew

- St Augustine's Reach, Pero's Bridge

- Bathurst Basin

- Queen Square

- Bristol Temple Meads railway station

- Castle Park

- Redcliffe Quay

- Baltic Wharf marina

- Cumberland Basin & Brunel Locks

- The New Cut

- Netham Lock, entrance to the Feeder Canal

- Totterdown Basin

- Temple Quay

- St Augustine's Parade

- Canons Marsh, including Millennium Square and At-Bristol

- Underfall Yard

- Bristol Bridge

History of Bristol docks

Bristol grew up on the banks of the Rivers Avon and Frome. Since the 13th century, the rivers have been modified for use as docks including the diversion of the River Frome into an artificial deep channel known as Saint Augustine's Reach, which flowed into the River Avon.[2][3] Saint Augustine's Reach became the heart of Bristol's docks with its quays and wharfs.[3] The River Avon within the gorge, and the River Severn into which it flows, has tides which fluctuate about 30 ft (9 m) between high and low water. This means that the river is easily navigable at high-tide but reduced to a muddy channel at low tide in which ships would often run aground. Many ships were deliberately stranded in the harbour for unloading, giving rise to the phrase "shipshape and Bristol fashion" to describe boats capable of taking the strain of repeatedly being stranded.[4][5]

As early as 1420, vessels from Bristol were regularly traveling to Iceland and it is speculated that sailors from Bristol had made landfall in the Americas before Christopher Columbus or John Cabot.[6] After Cabot arrived in Bristol, he proposed a scheme to the king, Henry VII, in which he proposed to reach Asia by sailing west across the north Atlantic. He estimated that this would be shorter and quicker than Columbus' southerly route. The merchants of Bristol, operating under the name of the Society of Merchant Venturers, agreed to support his scheme. They had sponsored probes into the north Atlantic from the early 1480s, looking for possible trading opportunities.[6] In 1552 Edward VI granted a Royal Charter to the Merchant Venturers to manage the port.[7]

By 1670, the city had 6,000 tons of shipping, of which half was used for importing tobacco. By the late 17th and early 18th century, this shipping was also playing a significant role in the slave trade.[6]

Construction of the floating harbour

In the 18th Century, the docks in Liverpool grew larger and so increased competition with Bristol for the tobacco trade. Coastal trade was also important, with the area called "Welsh Back" concentrating on trows with cargoes from the Slate industry in Wales, stone, timber and coal.[8] The limitations of Bristol's docks were causing problems to business, so in 1802 William Jessop proposed installing a dam and lock at Hotwells to create the harbour. The £530,000 scheme was approved by Parliament, and construction began in May 1804. The scheme included the construction of the Cumberland Basin, a large wide stretch of the harbour in Hotwells where the Quay walls and bollards have listed building status.[9]

The tidal new cut was constructed from Netham to Hotwells, with another dam installed at this end of the harbour. The Feeder Canal between Temple Meads and Netham provided a link to the tidal river so that boats could continue upstream to Bath. However, the new scheme required a way to equalise the levels inside and outside the Dock for the passage of vessels to and from the Avon, and bridges to cross the water. Jessop built Cumberland Basin with two entrance locks from the tidal Avon, of width 45 ft (13.7 m) and 35 ft (10.7 m), and a junction lock (width 45 ft) between the Basin and what became known as the Floating Harbour. This arrangement provided flexibility of operation with the Basin being used as a lock when there were large numbers of arrivals and sailings. The harbour was officially opened on 1 May 1809.[10]

Patterson's yard within the harbour was used for the construction of many ships notably Brunel's SS Great Western in 1838 and the SS Great Britain in 1843.[1] They were some of the largest ships to have been built at the time[1] and ironically hastened the decline of the city docks by proving the feasibility of large ships.[6] The SS Great Britain was being towed away from her builders, to have her 1,000 hp engines and interior fitted out on the River Thames,[1] but unfortunately her 48 ft (14.6 m) beam was too big to pass through the lock. The SS Great Britain was moored in the Floating Harbour until December 1844 before proceeding into Cumberland Basin after coping stones and lock gate platforms were removed from the Junction Lock.[10]

19th century improvements

The harbour cost more than anticipated and high rates were levied to repay loans, reducing any benefit the new harbour had at drawing companies back from Liverpool.[6] In 1848 the city council bought the docks company to force down the rates. They employed Isambard Kingdom Brunel to make improvements, including new lock gates, a dredger and sluice gates designed to reduce siltation.

By 1867, ships were getting larger and the meanders in the river Avon prevented boats over 300 ft (91 m) from reaching the harbour. A scheme to install a much larger lock at Avonmouth to make the entire river a floating harbour, and to straighten the sharper bends, was dropped after work began on the much cheaper docks at Avonmouth and Portishead. The present entrance lock was designed by Thomas Howard and opened in July 1873. This has a width of 62 ft (18.9 m) and is the only entrance lock now in use at the City Docks.[10]

From 1893 until 1934 the Clifton Rocks Railway provided an underground funicular railway link from the western end of the harbour, which is close to the locks, into Clifton.[3]

Underfall Yard

The docks maintenance facility was established on the land exposed by the damming of the river to construct the harbour and remains sited at this location to the present day. William Jessop had created a weir in the dam at Underfall to allow surplus water to flow back into the New Cut, this was known as the 'Overfall'. By the 1830s, the Floating Harbour was suffering from severe silting. Isambard Kingdom Brunel was, however, able to devise a solution to this problem. In place of the Overfall he constructed three shallow sluices and one deep scouring sluice between the harbour and the New Cut, together with a dredging vessel. This drag boat would scrape the silt away from the quay walls. When the deep sluice opened at low tide, a powerful undertow sucked the silt into the river to be carried away on the next tide. The shallow sluices enabled adjustment of the dock water level according to weather conditions.[11]

Several old buildings, which date from the 1880s, remain at Underfall Yard and have listed building status. The octagonal brick and terracotta chimney of the hydraulic engine house dates from 1888, and is grade II* listed,[12] as is the hydraulic engine house itself. It is built of red brick with a slate roof and contains pumping machinery, installed in 1907 by Fullerton, Hodgart and Barclay of Paisley, which powers the dock's hydraulic system of cranes, bridges and locks.[13] The former pattern-maker's shop and stores date from the same period and are grade II listed,[14] as are the Patent slip and quay walls.[15]

Warehouses

A large number of warehouses were built around the harbour for storage and trade. Many survive today and some are being converted into apartment blocks but many have been demolished as part of the regeneration of the area. One which has survived is the "A Bond Tobacco Warehouse", which was built in 1905 and was the first of the three brick built bonded warehouses in the Cumberland Basin, and is a grade II listed building.[16] Robinson's Warehouse built in 1874 by William Bruce Gingell,[17] and the Granary[18] on Welsh Back are examples of the Bristol Byzantine style with coloured brick brick and Moorish arches.

The Arnolfini art gallery occupies Bush House, a 19th century Grade II* listed tea warehouse.[19] and the Watershed Media Centre occupies another disused warehouse.

20th century improvements

In 1908, the Royal Edward Dock was built in Avonmouth and in 1972 the large deep water Royal Portbury Dock was constructed on the opposite side of the mouth of the Avon, making Bristol Harbour redundant as a freight dock.

Amey Roadstone Corporation (formerly T B Brown and Holmes Sand & Gravel) sand dredgers worked from Poole's Wharf in Hotwells until 1991. Occasionally coastal trading vessels enter the Cumberland Basin to be loaded with large steel silos manufactured by Braby Ltd at their nearby Ashton Gate works.[20]

The old Junction Lock swing bridge is powered by water pressure from the Underfall Yard hydraulic engine house at 750 psi (52 bar). The new Plimsoll Bridge, completed in 1965, has a more modern electro-hydraulic system using oil at a pressure of 4,480 psi (309 bar).[10]

Regeneration of the harbourside

Since the 1980s, millions of pounds have been spent regenerating the harbourside. Construction of Pero's footbridge which now links the At-Bristol exhibition with other Bristol tourist attractions took place in 1999. In 2000, the At-Bristol centre opened on semi-derelict land at Canon's Marsh and some of the existing Grade II listed buildings were refurbished and reused. It was funded with UK£44.3 million from the National Lottery, the Millennium Commission, South West of England Regional Development Agency, and a further £43.4 million from Bristol city council and commercial partners, including Nestlé.[21] Private investors are also constructing studio apartment buildings.[22]

The regeneration of the Canon's Marsh area is expected to cost £240 million.[21] Crest Nicholson were the lead developers, constructing 450 new flats, homes and waterside offices.[23] It is being carried out under the guidance of The Harbourside Sponsors’ Group, which is a partnership between the City Council, key stakeholders, developers, businesses, operators and funders.[22]

The Cumberland basin is used by a variety of small boats from sailing clubs and is surrounded by tourist attractions. The old hydraulic pumping station has been converted into a public house and is a Grade II listed building.[24]

Gallery

-

Bristol Bridge and the Floating Harbour, seen from a tethered passenger balloon. Most of the central part of the City of Bristol is shown here

-

Bristol Bridge and the Floating Harbour

-

Ferry in the harbour

-

Replica sailing ship in Bristol Floating harbour, July 2004

-

Industrial Museum from the pedestrian bridge

-

Floating Restaurant in the harbour

-

The Matthew turning outside the Arnolfini during a harbour cruise

-

Baltic Wharf Marina

References

- ^ a b c d Becket, Derrick (1980). Brunel's Britain. Newton Abbott: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-7973-9.

- ^ "Picturing the Docks". Responses: Andy Foyle. Retrieved 2007-01-28.

- ^ a b c Watson, Sally (1991) Secret Underground Bristol. Bristol: Bristol Junior Chamber. ISBN 0-907145-01-9

- ^ "Ship-shape and Bristol fashion". The phrase finder. Retrieved 2006-08-25.

- ^ Wilson, Ian (1996). John Cabot and the Matthew. Tiverton: Redcliffe Press. ISBN 1900178206.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d e Brace, Keith (1996). Portrait of Bristol. London: Robert Hale. ISBN 0709154356.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Bristol harbour history". Tangaroa Bristol. Retrieved 2007-05-26.

- ^ Pearson, Michael (2003). Kennet & Avon Middle Thames:Pearson's Canal Companion. Rugby: Central Waterways Supplies. ISBN 0-907864-97-X.

- ^ "Quay walls and bollards". Images of England. Retrieved 2006-08-18.

- ^ a b c d "The creation of Bristol City docks". Farvis. Retrieved 2006-08-18.

- ^ "Underfall Boatyeard history". Retrieved 2006-08-18.

- ^ "Chimney of hydraulic engine house". Images of England. Retrieved 2006-08-18.

- ^ "hydraulic engine house". Images of England. Retrieved 2006-08-18.

- ^ "former pattern-maker's shop and stores". Images of England. Retrieved 2006-08-18.

- ^ "Patent slip and quay walls". Images of England. Retrieved 2006-08-18.

- ^ "A Bond Tobacco Warehouse". Images of England. Retrieved 2006-08-18.

- ^ "Robinson's Warehouse". Looking at Buildings. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ^ "The Granary and attached area walls". Images of England. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ^ "Bush House". Images of England. Retrieved 2006-08-18.

- ^ "BRABY MAKE LIGHT WORK OF MAMMOTH SILO DELIVERY". Braby Ltd. Retrieved 2007-01-28.

- ^ a b "Development areas in Bristol". Bristol City Council. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

- ^ a b "Bristol - Harbourside Management". BERI Virtual Masterplan. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

- ^ "New Harbourside development given the green light". BBC News. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

- ^ "The Pump House Public House". Images of England. Retrieved 2006-08-18.

External links

- Bristol City Council: Harbour events and attractions Marine and waterway services

- About Bristol: History of the Harbour

- A history of the docks

- Bristol Packet Boat Trips

- Bristol City Docks