Paradise Lost

Title page of the first edition (1668) | |

| Author | John Milton |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Epic poem |

| Publisher | Samuel Simmons (original) |

Publication date | 1667 |

| Publication place | England |

| Media type | |

| ISBN | NA Parameter error in {{ISBNT}}: invalid character |

Paradise Lost is an epic poem in blank verse by the 17th-century English poet John Milton. It was originally published in 1667 in ten books. A second edition followed in 1674, redivided into twelve books (in the manner of the division of Virgil's Aeneid) with minor revisions throughout and a note on the versification. The poem concerns the Judeo-Christian story of the Fall of Man; the temptation of Adam and Eve by the fallen angel Satan and their expulsion from the Garden of Eden. Milton's purpose, stated in Book I, is to "justify the ways of God to men"[1] and elucidate the conflict between God's eternal foresight and free will.

In the early nineteenth century, the Romantics began to regard Satan as the protagonist of the epic. Milton presents Satan as an ambitious and proud being who defies his creator, omnipotent God, and who wages war on Heaven, only to be defeated and cast down. Indeed, William Blake, a great admirer of Milton and illustrator of the epic poem, said of Milton that "he was a true Poet, and of the Devil's party without knowing it."[2] Some commentators regard the character of Satan as a precursor of the Byronic hero.[3]

Milton worked for Oliver Cromwell and the Parliament of England and thus wrote first-hand for the Commonwealth of England. Arguably, the failed rebellion and the reinstallation of the monarchy left him to explore his losses within Paradise Lost.

Milton incorporates Paganism, classical Greek references and Christianity within the story. The poem grapples with many difficult theological issues, including fate, predestination, and the Trinity.

Synopsis

The story is divided into twelve books, like the Aeneid of Virgil. The book length varies — the longest being Book IX, with 1189 lines and the shortest, Book VII, having 640. Each book is preceded by a summary titled "The Argument". The poem follows the epic tradition of starting in medias res (Latin for in the midst of things), the background story being told in Books V-VI.

Milton's story contains two arcs: one of Satan (Lucifer) and another of Adam and Eve. Satan's story is a homage to the old epics of warfare. It begins after Satan and the other rebel angels have been defeated and cast down by God into Hell. In Pandæmonium, Satan must employ his rhetorical ability to organize his followers; he is aided by his lieutenants Mammon and Beelzebub. Belial and Moloch are also present. At the end of the debate, Satan volunteers himself to poison the newly-created Earth. He braves the dangers of the Abyss alone in a manner reminiscent of Odysseus or Aeneas.

The other story is a fundamentally different, new kind of epic: a domestic one. Adam and Eve are presented for the first time in Christian literature as having a functional relationship while still without sin. They have passions, personalities, and sex. Satan successfully tempts Eve by preying on her vanity and tricking her with rhetoric, and Adam, seeing Eve has sinned, knowingly commits the same sin by also eating of the fruit. In this manner Milton portrays Adam as a heroic figure but also as a deeper sinner than Eve. They again have sex, but with a new found lust that was previously not present. After realizing their error in consuming the "fruit" from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, they fight. However, Eve's pleas to Adam reconcile them somewhat. More important, her encouragement enables Adam and Eve both to approach God, to "bow and sue for grace with suppliant knee," and to receive grace from God. Adam goes on a vision journey with an angel where he witnesses the errors of man and the Great Flood, and he is saddened by the sin that they have released through the consumption of the fruit. However, he is also shown hope – the possibility of redemption – through a vision of Jesus Christ. They are then cast out of Eden and the archangel Michael says that Adam may find "A paradise within thee, happier far." They now have a more distant relationship with God, who is omnipresent but invisible (unlike the previous tangible Father in the Garden of Eden).

The contents of the 12 books are:

Book I: In a long, twisting opening sentence mirroring the epic poetry of the Ancient Greeks, the poet invokes the "Heavenly Muse" (the Holy Spirit) and states his theme, the Fall of Man, and his aim, to "justify the ways of God to men."[1] Satan, Beelzebub, and the other rebel angels are described as lying on a lake of fire, from where Satan rises up to claim hell as his own domain and delivers a rousing speech to his followers ("Better to reign in hell, than serve in heav'n"). Milton breaks with the tradition of the ten syllable meter with the first line, using 11 meters rather than ten. The logic of Satan (Satanic Logic) is also introduced with the following quote, "The Mind is its own Place, and there within, can make a Hell out of Heaven, or a Heaven out of Hell".

Book II: Satan and the rebel angels debate whether or not to conduct another war on Heaven, and Beelzebub tells them of a new world being built, which is to be the home of Man. Satan decides to visit this new world, passes through the Gates of Hell, past the sentries Sin and Death, and journeys through the realm of Chaos. Here, Satan is described as giving birth to Sin with a burst of flame from his forehead, as Athena was born from the head of Zeus.

Book III: God observes Satan's journey and foretells how Satan will bring about Man's Fall. God emphasizes, however, that the Fall will come about as a result of Man's own free will and excuses Himself of responsibility. The Son of God offers himself as a ransom for Man's disobedience, an offer which God accepts, ordaining the Son's future incarnation and punishment. Satan arrives at the rim of the universe, disguises himself as an angel, and is directed to Earth by Uriel, Guardian of the Sun.

Book IV: Satan journeys to the Garden of Eden, where he observes Adam and Eve discussing the forbidden Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. Satan, observing their innocence and beauty hesitates in his task, but concludes that "reason just,/ Honour and empire"[4] compel him to do this deed which he "should abhor." Satan tries to tempt Eve while she is sleeping, but is discovered by the angels. The angel Gabriel expels Satan from the Garden.

Book V: Eve awakes and relates her dream to Adam. God sends Raphael to warn and encourage Adam: they discuss free will and predestination and Raphael tells Adam the story of how Satan inspired his angels to revolt against God.

Book VI: Raphael goes on to describe further the war in Heaven and explains how the Son of God drove Satan and his minions down to Hell.

Book VII: Raphael explains to Adam that God then decided to create another world (the Earth), and he warns Adam again not to eat the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge, for "in the day thou eat'st, thou diest;/ Death is the penalty imposed, beware,/ And govern well thy appetite, lest Sin/ Surprise thee, and her black attendant Death".

Book VIII: Adam asks Raphael for knowledge concerning the stars and the heavenly orders; Raphael warns that "heaven is for thee too high/ To know what passes there; be lowly wise", and advises modesty and patience.

Book IX: Satan returns to Eden and enters into the body of a sleeping serpent. The serpent tempts Eve to eat the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge. She eats and takes some fruit for Adam. Adam realizes that Eve has been tricked, but eats of the fruit, deciding that he would rather die with Eve than live without her. At first the two become intoxicated by the fruit, and both become lustful and engage in sexual intercourse; afterwards, in their loss of innocence Adam and Eve cover their nakedness and fall into despair: "They sat them down to weep, nor only tears/ Rained at their eyes, but high winds worse within/ Began to rise, high passions, anger, hate,/ Mistrust, suspicion, discord, and shook greatly/ Their inward state of mind."

Book X: God sends his Son to Eden to deliver judgment on Adam and Eve, and Satan returns in triumph to Hell.

Book XI: The Son of God pleads with God on behalf of Adam and Eve. God decrees that the couple must be expelled from the Garden, and the angel Michael descends to deliver God's judgment. Michael begins to unfold the future history of the world to Adam.

Book XII: Michael tells Adam of the eventual coming of the Messiah, before leading Adam and Eve from the Garden. They have lost the physical Paradise but now have the opportunity to enjoy a "Paradise within … happier farr." The poem ends: "The World was all before them, where to choose Their place of rest, and Providence Their guide: They hand in hand with wandering steps and slow, Through Eden took Their solitaire way."[5] Milton has connected the condition of Adam and Eve with the condition of the reader of the epic.

Subject matter

Paradise Lost is an epic account of the Fall of Man. Milton begins his poem by invoking the aid of the (Holy) Spirit for his task, and sets forth the purpose of his song: "that ... I may assert the Eternal Providence and justify the ways of God to man".

The poem then depicts Satan and his fallen angels, already expelled from heaven and burning in the fire, as they start to talk among themselves. The rest of Books I and II, are then recounted from the perspective of Satan and his minions. Satan goes on to tell how those of Hell deliberated with him as to whether or not they should war with those in heaven yet again and attempt to overthrow it. Once agreed upon, Satan struggles through Chaos from Heaven to Hell. Traditional Christians may argue that this is an unbiblical ability according to the Gospel of Luke chapter 16 in the story of the rich man and Lazarus, "…between us and you there is a great gulf fixed: so that they which would pass from hence to you cannot; neither can they pass to us, that would come from thence"[6] Perhaps the ability to transfer from one immaterial place to another differs between composites of form and matter or soul and body (humans) and pure spirit. However, this is not even an issue in this context, even though Hell is a state of mind, "the hell within him; for within him Hell he brings, and round about him, nor from Hell one step, no more than from himself, can fly by change of place".[7]

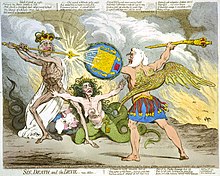

Later on in the poem, Satan goes on to introduce Death and Sin. Sin was birthed from the head of Satan, an allusion to the birth of the Greek god Athena. Sin is half beautiful woman and half serpent, the lower portion of her body destroyed after giving birth to Death. Hell-hounds are attached to the waist of Sin, constantly running in and out of her being re-birthed and devouring Sin's body. In book 4, Adam and Eve are introduced for the first time. Milton’s idea of marriage is very much influenced in this section. Their relationship is one of inequality, but not a relation of domination or hierarchy. There is a mutual friendship between the two and they also model the ideal ruler and subject. For Milton, this marriage is a political ideal just as much as it is a personal ideal. Satan also describes their personalities. Eve is described as a "'coy', flirtatious, beautiful, sex object that Adam is overwhelmed by"[8] or "Too much of Ornament";[9] Adam is seen as more of an intellectual.[citation needed] Though there is no sin within paradise, Adam and Eve have an argument about the care of the land. Eve thinks the garden is growing too fast and that the two should split up while working to cover more ground, thus accomplishing more. Adam disagrees and says that time is not an issue for them, therefore they were meant to enjoy their work and not rush it. This disagreement would begin the stirring up their hearts, making them more vulnerable to the temptation that was to come. Adam consents to Eve’s wishes and they split up during their work. Satan, as the serpent in the garden, made ready to fool Eve through the process of reduction.

In the last three chapters after the Fall, the Son of God intercedes for Adam and Eve and the Father accepts. However, he commands the angel Michael to ban Adam and Eve from the garden. In doing so, Michael gives Adam a vision of the Flood, and life and death of Christ, revealing to him the way of redemption. Adam and Eve’s lives carry on but they are driven out from the Garden of Eden.

Character analysis

Satan: Satan is the first major character introduced in the poem. He is introduced in Hell after a failed rebellion to take control of Heaven from God. Satan’s desire to rebel against his creator stems from his unwillingness to accept the fact that he is a created being and that he is not self sufficient, which roots in turn from his extreme Pride. One of the ways he tries to justify his rebellion against God is by claiming that he and the angels are self-created, declaring that the angels are "self-begot, self-raised",[10] thereby eliminating God’s authority over them as their creator.[citation needed] Satan’s views are grossly distorted, however. Satan is narcissistic to the point of being delusional, as shown by his encounter with Sin and Death.[who?] Although they are introduced as if they are separate entities from Satan, Sin and Death can both be read as delusions of Satan’s mind.[11] Sin describes herself as sprouting out of Satan’s mind at the time he conceived of his plot to overthrow God [compare with the New Testament book of James, Chapter 1, verse 15], which perhaps could be taken for the fact that she is only a part of Satan, specifically his sinful scheme to overthrow God that he is projecting into the world. She is described as originally having the same features as Satan, which shows the perversion of his narcissism, because Satan engages Sin in incestuous intercourse. Satan is narcissistic to the point of being aroused by his own image, and from his incest with his "daughter" Sin, Death is born.[12] Death too, however, may be a delusion of Satan’s mind, having no substance or form, no real power. This reflects Milton’s Christian theology, because Christianity sees death as having no real power also.[13] Satan’s delusion is also shown when he leaves Hell. He goes up to the gates, which fly quickly open before him. Satan sets out to portray God as a tyrant, yet here Milton shows us that Satan is not even locked in Hell. Milton portrays Hell also as a state of Satan’s mind in the opening of Book 4, talking of how Satan has "Hell within him; for within him Hell/ He brings…".[14] Milton shows us that Satan is creating his own internal Hell by his delusions and narcissism.[15] The fact that Satan is such a driving force within the poem has been the subject of a large amount of scholarly debate, with positions ranging anywhere from views such as that of William Blake who stated that Milton "wrote in fetters when wrote of Angels and God, and at liberty when of Devils and Hell, is because he was a true Poet and of the Devil’s party without knowing it"[16] to the critic William H. Marshall’s interpretation that the poem is in fact a Christian moral tale, but that Milton fails to portray his original intent because the reader’s emotional reaction to the story must be "subordinated to [his] intellectual response to the explicit assertion in the final books of the Paradox of the Fortunate Fall."[17]

Adam: Adam is the first human in Eden created by God. He is the more intellectual of the two, with Eve being more rooted in experience. Positively, Adam is a model of a good ruler, gently leading Eve during their first encounter away from her reflection, using force but not excessively. Although he and Eve are not equal in the story, Adam is not an oppressive ruler.[18] He and Eve have a mutually dependent relationship. This illustrates Milton’s views on the relationship between ruler and subject as well as husband and wife.[19] Negatively, he like Satan shares the problem of lack of self-knowledge, but unlike Satan who is totally self-absorbed and narcissistic, Adam’s problem stems from the fact that he seems to be in danger of losing sight of himself. The cause of his loss of self is the beauty of Eve, which he complains about during his discourse with Raphael, saying that she is "Too much of Ornament".[20] He talks anxiously of how he feels like he is becoming dependent on Eve, who conversely seems to be self-sufficient and naturally independent. Adam is distraught by this because it would seem to him that she should be the one dependent because he was created first and she was made from a part of him, and yet as it stands he is becoming obsessed with Eve almost to the point of idolizing her.[21] There is also an element of heresy to Adam even before the Fall. He wishes to avoid confrontation with Satan completely, even to the fact of being cowardly about it, denying the idea of the "felix culpa", that the Fall might not be a bad thing, perhaps part of God’s greater plan.[22]

Eve: Eve is the second human created, taken from one of Adam’s ribs and formed into a female form of Adam. Positively, she is the model of a good subject and wife. She consents to Adam leading her away from her reflection when they first meet, trusting Adam’s authority in their relationship.[23] She is very beautiful, so much so that she is almost a danger to herself and Adam. Her beauty not only obsesses Adam, but also herself. After she is first born, she gazes at her own reflection in a pool of water and is transfixed by her own image. Even after Adam calls out to her she returns to her image. It is not until God tells her to go to Adam that she consents to being led away from the pool. This shows that from the beginning she is in danger of narcissism, much like Satan. She is also the first to come into contact with satanic influence; Satan worms his way into one of her dreams to tempt her. After this incident she seems to develop the independent streak that so perplexes Adam during his conversation with Raphael, wanting to go off by herself to work in the garden. She also develops the Satanic view of wanting to organize the garden, wishing to split up to get more work done, worrying that the garden is "messy" and wishing to impose some kind of order on it, which is Satan’s wish as well.[24] She eventually does give into temptation, being the first to eat of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, effectively causing the Fall. She is not portrayed in a totally negative manner in the story, however; during her argument with Adam about whether or not they should split up, Adam says they should stay together in order to avoid temptation and implying that even to be tempted would be dishonourable to them, which is a flawed argument. Eve responds by taking a heroic stance, saying that if they would give into temptation that easily that their virtue must not have been very strong to begin with.[25] This is not the only time Eve shows a heroic side either, despite her failings. After the Fall, Adam begins to blame her for everything that has gone wrong, acting as if she alone is the cause despite the fact that he willingly chose to sin also. Eve makes her stand here by humbly taking all the verbal abuse that Adam gives to her, instead of arguing and causing a further rift between them. By taking everything upon herself she is portrayed as a Christ-figure, accepting fault that is not hers and bearing it for the sake of the future of humanity.[26]

The Son of God: the Son of God in Paradise Lost is Christ, though he is never named explicitly, since He has not yet entered human form. After the Father explains to him how Adam and Eve will fall, and how the rest of humanity will be doomed to follow them in their cursed footsteps, the Son heroically proclaims that he will take the punishment for humanity. The Son gives hope to the poem because although Satan conquers humanity by successfully tempting Adam and Eve, the victory is temporary because the Son will save the human race.[27] Interestingly enough, the Son shows a major break with orthodox religious thought on Milton’s part; the accepted belief at the time was that the Trinity were all part of the one Godhead, and thus all created at the same time, and yet Milton portrays the Son as being created after the Father.[28]

God the Father: God the Father is the creator of Eden, Heaven, Hell, and of each of the main characters in the poem. He is an all-powerful being who cannot be overthrown by even the one-third of the angels that Satan incites against Him. The poem portrays God’s process of creation in the way that Milton believed it was done, that God created Heaven, Earth, Hell, and all the creatures that inhabit these separate planes from part of himself, not out of nothing.[29] Thus according to Milton, what gives God his ultimate authority is the fact that he is the "author" of creation. Satan tries to justify his rebellion by denying this aspect of God and claiming self-creation, but he admits to himself that this is not the case, and that God "deserved no such return from me, whom he created what I was”.[30][31][32][citation needed]

Composition

Milton began writing the epic in 1658 at the age of fifty, during the last years of the English Republic. The infighting among different military and political factions that doomed the Republic may show up in the Council of Hell scenes in Book II. Although he probably finished the work by 1664, Milton did not publish until 1667 on account of the Great Plague and the Great Fire.

Milton composed the entire work while completely blind. It is presumed he had glaucoma, necessitating the use of paid amanuenses and his daughters. The poet claimed that a divine spirit inspired him during the night, leaving him with verses that he would recite in the morning.

The 3rd Norton edition of Paradise Lost ignores the punctuation found in the surviving manuscript draft on the grounds that it was inserted by the printer, but this procedure has been challenged. Even into the mid-18th century a variety of publications included a wide array of spellings of even the same word within the same text.

Context

The book is influenced by the Bible, Milton's own Puritan upbringing and religious perspective (including elements of Arminianism, Phineas Fletcher, Edmund Spenser, and the ancient poets Virgil, Ovid and Theocritus).

Milton wrote the entire work with the help of secretaries and friends, notably Andrew Marvell, after losing his sight.

Later in life, Milton wrote the much shorter Paradise Regained, charting the temptation of Christ by Satan, and the return of the possibility of paradise. This sequel has never had a reputation equal to the earlier poem.

Themes

Marriage

On the surface Paradise Lost appears to be a general biblical story depicting creation and the fall of Adam and Eve. Digging deeper into the plot of the poem, however, several critics have noted the relationship between Adam and Eve, and how it specifically reflects Milton’s views on marriage.

Milton first presents Adam and Eve in Book 4 and the pair is viewed in impartiality. The relationship between Adam and Eve is one of ". . . mutual dependence, not a relation of domination or hierarchy."[33] While the author does place Adam above Eve in regards to his intellectual knowledge, and in turn his relation to God, he also grants Eve the benefit of knowledge through experience. Hermine Van Nuis clarifies that although there is a sense of stringency associated with the specified roles of the male and the female, each unreservedly accepts the designated role because it is viewed as an asset.[34] Instead of believing that these roles are forced upon them, each uses the obligatory requirement as a strength in their relationship with each other. These minor discrepancies reveal the author’s view on the importance of mutuality between a husband and a wife.

When examining the relationship between Adam and Eve, critics have had the tendency to accept an either Adam- or Eve-dominated point of view in relation of hierarchy and importance to God. David Mikics argues, however, that these positions ". . . overstate the independence of the characters’ stances, and therefore miss the way in which Adam and Eve are entwined with each other".[35] Milton’s true vision reflects one where the husband and wife (in this instance, Adam and Eve) depend on each other and only through each other’s differences are able to thrive.[35] While most readers believe that Adam and Eve fail because of their fall from paradise, Milton would argue that the strengthening of their love for one another that results is true victory.

Although Milton does not directly mention divorce in the actual context of Paradise Lost, critics have presented solid theories on Milton’s view of divorce based on inferences found within the poem. Other works by Milton have expressed that the noted English author viewed marriage as an entity separate from the church. More specifically, however, in relation to Paradise Lost, Biberman entertains the idea that ". . . marriage is a contract made by both the man and the woman".[36] Based on this inference, Milton would believe that both man and woman would have equal access to divorce, as they do to marriage.

Idolatry

Owing to his Protestant views on politics and religion in 17th century England, contemporaries usually criticized Milton’s ideas and considered him as something of a radical. One of Milton’s greatest and most controversial arguments revolves around his concept of what is idolatrous and as critics have noted, the topic is deeply embedded in Paradise Lost.

Milton’s first criticism of idolatry lies in the theory of constructing temples and other buildings to serve as places of worship. In Book 11 of Paradise Lost, Adam tries to atone for his sins by offering to build altars to worship God and in response, the Angel Michael explains that Adam does not need to build physical objects to experience the presence of God.[37] Joseph Lyle points to this example and further explains that "When Milton objects to architecture, it is not a quality inherent in buildings themselves he finds offensive, but rather their tendency to act as convenient loci to which idolatry, over time, will inevitably adhere."[38] Even if the idea is pure in nature, Milton still believes that it will unavoidably lead to idolatry simply because of the nature of humans. Instead of placing their thoughts and beliefs into God, as they should, humans tend to turn to erected objects and falsely invest their faith. While Adam attempts to build an altar for God, critics have noted that Eve is also guilty of idolatry, but in a different manner. Harding believes Eve’s narcissism and obsession with herself also constitutes idolatry.[39] Specifically, Harding claims that ". . . under the serpent’s influence, Eve’s idolatry and self-deification foreshadow the errors into which her 'Sons' will stray."[39] Much like Adam, Eve falsely places her faith into herself, the Tree of Knowledge, and to some extent, the Serpent, all of which do not compare to the ideal nature of God.

Furthermore, Milton makes his views on idolatry more explicit with the creation of Pandemonium and the exemplary allusion to Solomon’s temple. In the beginning of Paradise Lost, as well as throughout the poem, several references are made to the rise and eventual fall of Solomon’s temple. Critics elucidate that "Solomon’s temple provides an explicit demonstration of how an artifact moves from its genesis in devotional practice to an idolatrous end."[40] This example, out of the many presented, conveys Milton’s views on the dangers of idolatry most clearly. Even if one builds a structure in the name of God, even the best of intentions can become immoral. In addition, critics have noted a parallel between Pandemonium and Saint Peter's Basilica,[citation needed] and the Pantheon as well. The majority of these similarities revolve around a structural likeness, but as Lyle explains, they play a much greater role. By linking Saint Peter’s Basilica and the Pantheon to Pandemonium, an ideally false structure, the two famous buildings take on a false meaning as well.[41] This comparison best represents Milton’s Protestant views in that it rejects both the purely Catholic perspective and the Pagan perspective.

In addition to rejecting Catholicism, Milton also revolted against the idea of a monarch ruling by divine right and saw the practice as idolatrous. Barbara Lewalski concludes that the theme of idolatry in Paradise Lost ". . . is an exaggerated version of the idolatry Milton had long associated with the Stuart ideology of divine kingship".[42] In the opinion of Milton, any object, human or non-human, that receives special attention that is befitting of God, is considered idolatrous.

Response and criticism

This epic has generally been considered one of the greatest works in the English language. In the verses below the portrait in the fourth edition, John Dryden linked Milton with Homer and Virgil, suggesting that Milton encompassed and surpassed both:[citation needed]

"Three Poets, in three distant Ages born,

Greece, Italy, and England did adorn.

The First in loftiness of thought surpass'd;

The Next in Majesty; in both the Last.

The force of Nature cou'd no farther goe:

To make a third she joynd the former two."

Since Paradise Lost is based upon scripture, its significance in the Western canon has been thought by some to have lessened due to increasing secularism. However, this is not the general consensus, and even academics who have been labelled as secular realize the merits of the work. In William Blake's The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, the "voice of the devil" argues:

- The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels & God, and at liberty when of Devils & Hell, is because he was a true Poet and of the Devil's party without knowing it.

This statement summarizes what would become the most common interpretation of the work in the twentieth century. Some critics, including C. S. Lewis and later Stanley Fish, reject this interpretation. Rather, such critics hold that the theology of Paradise Lost conforms to the passages of Scripture on which it is based.

The latter half of the twentieth century saw the critical understanding of Milton's epic shift to a more political and philosophical focus. Rather than the Romantic conception of the Devil as the hero of the piece, it is generally accepted that Satan is presented in terms that begin classically heroic, then diminish him until he is finally reduced to a dust-eating serpent unable even to control his own body. The political angle enters into consideration in the underlying friction between Satan's conservative, hierarchical view of the universe and the contrasting "new way" of God and the Son of God as illustrated in Book III.[citation needed] In other words, in contemporary criticism the main thrust of the work becomes not the perfidy or heroism of Satan, but rather the tension between classical conservative "Old Testament" hierarchs (evidenced in Satan's worldview and even in that of the archangels Raphael and Gabriel), and "New Testament" revolutionaries (embodied in the Son of God, Adam, and Eve) who represent a new system of universal organization.[citation needed] This new order is based not in tradition, precedence, and unthinking habit, but on sincere and conscious acceptance of faith and on station chosen by ability and responsibility.[citation needed] Naturally, this interpretation makes much use of Milton's other works and his biography, grounding itself in his personal history as an English revolutionary and social critic.[citation needed]

Samuel Johnson praised the poem lavishly, but conceded that "None ever wished it longer than it is."[43]

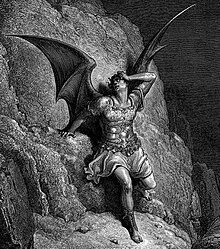

Iconography

The first illustrations were to the fourth edition of 1688, with one engraving prefacing each book, of which up to eight of the twelve were by Sir John Baptist Medina, one by Bernard Lens, and perhaps up to four (including Books I and XII, perhaps the most memorable) by another hand.[44] The most notable and popular illustrators of Paradise Lost are William Blake, Gustave Doré and Henry Fuseli; however, the epic's illustrators also include, among others, John Martin, Edward Burney, Richard Westall, Francis Hayman. Salvador Dalí executed a set of ten colour lithographs in 1974.[45] Strangely, two capriccios by Gian Battista Tiepolo were used to illustrate an Italian 18th century edition.[46] Surreal-visionary artist Terrance Lindall's rendition was published in 1982.[47]

Cultural significance

"Paradise Lost" has been the source of inspiration in several aspects of popular culture.

Literature

- In response to Paradise Lost William Blake composed an epic of his own, one of his 'illuminated book' entitled Milton: a Poem, between 1804 and 1810. It is Blake's longest poetic work, and features Milton himself as its hero; the poet returns from heaven and unites with Blake to explore the relationship between living writers and their predecessors, and to undergo a mystical journey to correct Milton's own spiritual errors, as perceived by Blake.

- Lord Byron's "dramatic poem" Manfred contains several allusions to Satan's speeches.

- The poem is the basis for the His Dark Materials trilogy by Philip Pullman, of which an excerpt was included in the first novel of the series, Northern Lights/The Golden Compass. The title of the trilogy is a direct quote from Paradise Lost, referring to Milton's depiction of Chaos as the realm of unformed matter.

- Neil Gaiman portrays Lucifer in a similar fashion when referenced, such as in his comic Murder Mysteries or The Sandman collections, the latter of which formed the basis for the branch-off series, Lucifer, which portrays him as an anti-hero after he retires from his position in Hell.

- Melkor and Sauron from J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth legendarium are inspired by Milton's portrayal of Satan.

- C.S. Lewis was inspired by Paradise Lost to write Perelandra, the second book of his Space Trilogy. Some have suggested that the Chronicles of Narnia villain White Witch may also be based on Milton's Satan.

- Mary Shelley's Frankenstein has many references to Paradise Lost, such as the Frankenstein monster's sympathetic view of Satan.

- Martin Amis's novel, The Information, which earned him an usually large advance, alludes to the poem.

- The Star Trek novel, To Reign in Hell, the story of the exile of Khan Noonien Singh, takes its title from the poem.

- Libba Bray's Rebel Angels quotes a part of Milton's Paradise Lost

- Wayne Barlowe's God's Demon is something of a retelling of Paradise Lost, concerning a demon who fights struggles for redemption after his fall.

Film

- The film Se7en includes a number of quotations from the poem.

- The film The Devil's Advocate contains several allusions to the poem. In this film Satan is named John Milton, after the author.

- The film The Crow alludes to the poem in several ways, including direct quotation.

- A new film of Paradise Lost is being produced by Damian Collier, executive producer of War of The Worlds and other films.[48]

- Ian McDiarmid who plays Palpatine, the main antagonist in the Star Wars saga, compared Palpatine to the Miltonic Satan. Satan as he appears in Paradise Lost also influenced the character Darth Vader/Anakin Skywalker

- The epic poem is briefly discussed by Donald Sutherland's character during a classroom scene in Animal House.

- Director Scott Derrickson is planning to film Paradise Lost in 3D. Discussing his interpretation of the story, he sees Satan as an anti-hero and not the villain, and that it shall be a "litmus test" for the audience when they stop sympathising with the character. Warner Bros. and Legendary Pictures are producing.[49]

- A few lines from the poem are narrated in a trailer for the Japanese anime film, The End of Evangelion

- A Parody film of Book 4 was released on youtube, depicitng Satan's struggle in a comedic fashion with a psychiatrist. [3] [4]

Music

- The poem influenced the musical composition The Creation by Joseph Haydn.

- Polish Classical composer Krzysztof Penderecki and metal bands Cradle of Filth and Symphony X have created musical works based upon the poem.

- Philadelphia rock band Milton and the Devils Party takes their name from William Blake's comment that Milton was "a true Poet and of the Devils party without knowing it" in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. Their song "Nude For Satan" includes a reference to Book 9 of Paradise Lost, quoting the phrase "stupidly good"; and their song "Heathen Eden" is based on Book 10 and the conflict between Adam and Eve consequent to the Fall.

- Death/Doom Metal band Paradise Lost was named after this piece of literature. In track 5 "Prime Evil" from their Bicycles and Tricycles release, Neville Jason reads various excerpts of Paradise Lost, mainly from book IV.

- Hollywood Undead's 2008 album Swan Songs features a track titled "Paradise Lost" which places Satan as the protagonist.

- Paradise Lost: Shadows and Wings is the title of a somewhat related opera by Eric Whitacre. The music of this opera is a mixture of many different styles of music including trance, classical, electronica, and traditional opera.

- The albums Paradise Lost and The Divine Wings of Tragedy by Progressive metal band Symphony X bear influences and themes from the epic.

- Peter Dizozza has written several pieces of music and also a play directly for Milton's Paradise Lost, most recently performed at a major Milton festival.[50] He also wrote the 30 minute "Incidental Music for Milton's Paradise Lost."

- The opening song of the anime Ga-Rei: Zero is called "Paradise Lost".

- Australian death metal outfit The Red Shore based their 2008 release Unconsecrated on the poem.

Art

- In 1974, surrealist artist Salvador Dalí illustrated Milton's Paradise Lost. As of July 2008, examples from this series can be viewed at the William Bennett Gallery in Manhattan.[51]

- In 1799 the Swiss/English artist John Henry Fuseli exhibited a series of paintings of works by Milton, particularly Paradise Lost. He hoped to establish a Milton gallery.

- Eugene Delacroix painted a famous illustration of "Milton Dictating Paradise Lost to his Daughters".[52]

- In 1930, Henry Lee Willet of Willet Stained Glass Studios created an eighteen-panel stained glass depiction of Paradise Lost for a bay window in McCartney Library at Geneva College.

Computer games

- A 2000 cyberpunk action role-playing game Deus Ex quotes lines from the poem.

- The 2006 historic turn-based strategy game Medieval II: Total War quotes the line, "Better to reign in hell, than serve in heav'n," among the series of quotations the game uses to form the game creators' interpretations of Crusades-era thinking and justification for waging war on the Muslim-controlled Holy Land.

- The 2008 cross-platform role-playing game Fallout 3 features the poem in game, and "reading" it results in a player's "speech" statistics rising.

Publication history

Online

Paradise Lost

- The Milton Reading Room XHTML version at Dartmouth

- Project Gutenberg text version 1

- Project Gutenberg text version 2

- Audiobook at LibriVox

- Paradise Lost: Parallel Prose Edition Regent College Publishing (Translated by Dennis Danielson, ISBN 978-1-57383-426-1) – includes Milton's original text on the left page and a modern translation on the right

- Paradise Lost Norton Critical Edition (2nd edition edited by Scott Elledge ISBN 0-393-96293-8; 3rd edition edited by Gordon Teskey ISBN 0-393-92428-9) – includes biographical, historical, and literary backgrounds, and criticism

- Paradise Lost Penguin Classics ISBN 0-14-042439-3.

- Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained Signet Classic Poetry ISBN 0-451-52792-5.

- Hughes, Merrit Y. ed. John Milton. The Complete Poems and Major Prose. New York, 1957. ISBN 0-87220-678-5.

- Fowler, Alastair, ed. Paradise Lost 2nd Edition, Longman, London, 1998. ISBN 0-582-21518-8.

- The Annotated Milton: Complete English Poems, edited by Burton Raffel, Bantam Classic (Random House), 1999. ISBN 0-553-58110-4.

- Paradise Lost and Other Poems, Signet Classic (Penguin Group), with introduction by Edward M. Cifelli, Ph.D. and notes by Edward Le Comte. New York, 2000.

- Paradise Lost, edited and with a note on the text by John T. Shawcross, Arion Press, 2002. Includes a portfolio of 13 facsimiles of William Blake's watercolor drawings depicting incidents from the text.

- Paradise Lost, Introduced by Philip Pullman, author of His Dark Materials trilogy. Oxford New York, Oxford University Press, 2005 - Illustrations taken from the first illustrated edition of 1688.

- Paradise Lost, edited by Roy C. Flannagan, Oxford, Oxford University Press (Paperback), 2008. ISBN 9780199554225.

See also

Footnotes

- ^ a b (Milton 1674, 4:26)

- ^ (Blake 1793)

- ^ (Eliot 1932)

- ^ (Milton 1674, 4:387-388)

- ^ (Milton 1674, 12:646-649)

- ^ (Blayney 1769).

- ^ (Black 2007, p. 20-22).

- ^ (Rust 2007),

- ^ (Milton 1674, 8:539)

- ^ Milton 1674, 5:60),

- ^ (Rust 2007)

- ^ (Rust 2007)

- ^ (Rust 2007)

- ^ (Milton 1674, 4:20-21)

- ^ (Rust 2007).

- ^ (Black 2007, p. 996)

- ^ (Marshal 1961, p. 19)

- ^ (Rust 2007)

- ^ (Rust 2007)

- ^ (Milton 1674, 8:539).

- ^ (Stone 1997, p. 35).

- ^ (Rust 2007)

- ^ (Rust 2007)

- ^ (Rust 2007)

- ^ (Rust 2007).

- ^ (Doerksen 1997, p. 126)

- ^ (Marshall 1961, p. 17).

- ^ (Rust 2007)

- ^ (Lehnhof 15)[citation needed]

- ^ (Milton 1674, 4:42-43;

- ^ Lehnhof 2008, p. 24)

- ^ http://books.google.com/books?id=_EUgAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA25&lpg=PA25&dq=deserved+no+such+return+from+me,+whom+he+created+what+I+was&source=web&ots=vmTMPRytr4&sig=Swnaw7hjY2PR_JdTVO5cJPXdEjE&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=1&ct=result#PPA25,M1

- ^ Rust (2007)

- ^ Van Nuis (2000, p. 50)

- ^ a b (Mikics 2004, p. 22)

- ^ (Biberman 1999, p. 137).

- ^ (Milton 1674, Book 11).

- ^ (Lyle 2000, p. 139).

- ^ a b (Harding 2007, p. 163)

- ^ (Lyle 2000, p. 140).

- ^ (Lyle 2000, p. 147).

- ^ Lewalski (2003, p. 223)

- ^ (Hill 1905, p. 1:183).

- ^ Illustrating Paradise Lost from Christ's College, Cambridge, has all twelve on line. See Medin'as article for more on the authorship, and all the illustrations, which are also in Commons.

- ^ William Bennett Gallery, with all illustrated

- ^ Svetlana Alpers 18th century AD, Art in America, March, 1995.

- ^ Terrance Lindall Recites Passages From John Milton’s Paradise Lost and Displays Original Illustrations, Williamsburg Art and Historical Center.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Joe Utichi (2008-12-12). "Exclusive: Milton's Paradise Lost Movie in 3D?". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2008-12-22.

- ^ [2]

- ^ "Le Paradis Terrestre". Salvador Dalí's Illustrations of John Milton's Paradise Lost. williambennettgallery.com. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- ^ Delcroix painting of Miton. Retrieved on 2009-01-23.

References

- Anderson, G (January 2000), "The Fall of Satan in the Thought of St. Ephrem and John Milton", Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies, 3 (1)

- Biberman, M (1999, January), "Milton, Marriage, and a Woman's Right to Divorce", SEL Studies in English Literature, 39 (1): 131–153

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Black, J, ed. (March 2007), "Paradise Lost", The Broadview Anthology of British Literature, vol. A (Concise ed.), Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press, pp. 998–1061, ISBN 978-1551118680, OCLC 75811389

- Blake, W. (1793), , London.

- Blayney, B, ed. (1769), , Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Bradford, R (1992, July), Paradise Lost (1 ed.), Philadelphia: Open University Press, ISBN 978-0335099825, OCLC 25050319

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Butler, G (1998, February), "Giants and Fallen Angels in Dante and Milton: The Commedia and the Gigantomachy in Paradise Lost", Modern Philosophy, 95 (3): 352–363

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Carey, J; Fowler, A (1971), The Poems of John Milton, London

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Doerksen, D (1997, December), "Let There Be Peace': Eve as Redemptive Peacemaker in Paradise Lost, Book X", Milton Quarterly, 32 (4): 124–130

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Eliot, T.S. (1957), On Poetry and Poets, London: Faber and Faber

- Eliot, T. S. (1932), "Dante", Selected Essays, New York: Faber and Faber, OCLC 70714546.

- Empson, W (1965), Milton's God (Revised ed.), London

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Forsyth, N (2003), The Satanic Epic, Princeton: Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691113395

- Frye, N (1965), The Return of Eden: Five Essays on Milton's Epics, Toronto: University of Toronto Press

- Harding, P (January 2007), "Milton's Serpent and the Pagan Birth of Error", SEL Studies in English Literature, 47 (1): 161–177

- Hill, G, ed. (1905), Samuel Johnson: The Lives of the English Poets, 3 vols., Oxford: Clarendon, OCLC 69137084[dead link]

- Kermode, F, ed. (1960), The Living Milton: Essays by Various Hands, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, ISBN 0710016662, OCLC 17518893

- Kerrigan, W, ed. (2007), The Complete Poetry and Essential Prose of John Milton, New York: Random House, ISBN 978-0679642534, OCLC 81940956

- Lewalski, B (January 2003), "Milton and Idolatry", SEL Studies in English Literature, 43 (1): 213–232

- Lewis, C.S. (1942), A Preface to Paradise Lost, London: Oxford University Press, OCLC 822692

- Lyle, J (January 2000), "Architecture and Idolatry in Paradise Lost", SEL Studies in English Literature, 40 (1): 139–155

- Marshall, W. H. (1961, January), "Paradise Lost: Felix Culpa and the Problem of Structure", Modern Language Notes, 76 (1): 15–20, doi:10.2307/3040476

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Mikics, D (2004), "Miltonic Marriage and the Challenge to History in Paradise Lost", Texas Studies in Literature and Language, 46 (1): 20–48

- Miller, T.C., ed. (1997), The Critical Response to John Milton's "Paradise Lost", Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0313289262, OCLC 35762631

- Milton, J (1674), (2nd ed.), London: S. Simmons

- Rajan, B (1947), Paradise Lost and the Seventeenth Century Reader, London: Chatto & Windus, OCLC 62931344

- Ricks, C.B. (1963), Milton's Grand Style, Oxford: Clarendon Press, OCLC 254429

- Stone, J.W. (1997, May), ""Man's effeminate s(lack)ness:" Androgyny and the Divided Unity of Adam and Eve", Milton Quarterly, 31 (2): 33–42

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Van Nuis, H (May 2000), "Animated Eve Confronting Her Animus: A Jungian Approach to the Division of Labor Debate in Paradise Lost", Milton Quarterly, 34 (2): 48–56

- Wheat, L (2008), Philip Pullman's His dark materials--a multiple allegory : attacking religious superstition in The lion, the witch, and the wardrobe and Paradise lost, Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus Books, ISBN 978-1591025894, OCLC 152580912

- Rust, Jennifer (November 2007), Interview, Saint Louis: Saint Louis University

- Rust, Jennifer. English Department. Xavier Hall, Saint Louis. 14 Nov 2007.

External links

- Paradise Lost at Curlie

- Yale English video lecture on Paradise Lost

- Librivox recording of Paradise Lost (mp3/ogg)

Online text

- Paradise Lost at Dartmouth's Milton Reading Room

- Paradise Lost Full text in frameless HTML, indexed by book

- Paradise Lost, read complete book online

Other information

- darkness visible – comprehensive site for students and others new to Milton: contexts, plot and character summaries, reading suggestions, critical history, gallery of illustrations of Paradise Lost, and much more. By students at Milton's Cambridge college, Christ's College.

- Norton Anthology of English Literature – Paradise Lost in Context – includes historical context, iconography, topical explorations and web resources

- "Free-Will Theodicy, Middle-Knowledge Theology, Ramist Linguistics, and Satanic Psychology in Paradise Lost" (pdf) by Horace Jeffery Hodges.

- "Free will and necessity in Milton's Paradise Lost" by Gilbert McInnis.

- Lecture on Milton's Paradise Lost by Ian Johnston - historical and religious background, overview of critical issues.

- Life of Milton by Samuel Johnson - includes perceptive comments on Paradise Lost.

- Selected bibliography at the Milton Reading Room – includes background, biography, criticism

- Study Resource for Paradise Lost

- Paradise Lost Study Guide