Fortification

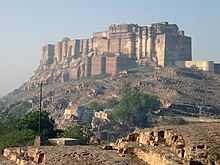

Fortifications are military constructions and buildings designed for defense in warfare and military bases. Humans have constructed defensive works for many thousands of years, in a variety of increasingly complex designs. The term is derived from the Latin fortis ("strong") and facere ("to make").

Nomenclature

Many military installations are known as forts, although they are not always fortified. Larger forts may class as fortresses, smaller ones formerly often bore the name of fortalices. The word fortification can also refer to the practice of improving an area's defense with defensive works. City walls are fortifications but not necessarily called fortresses.

The art of setting out a military camp or constructing a fortification traditionally classifies as castrametation, since the time of the Roman legions. The art/science of laying siege to a fortification and of destroying it has the popular name of siegecraft or 'siege warfare' and the formal name of poliorcetics. In some texts this latter term also applies to the art of building a fortification.

Fortification is usually divided into two branches, namely permanent fortification and field fortification. Permanent fortifications are erected at leisure, with all the resources that a state can supply of constructive and mechanical skill, and are built of enduring materials. Field fortifications are extemporized by troops in the field, perhaps assisted by such local labor and tools as may be procurable and with materials that do not require much preparation, such as earth, brushwood and light timber, or sandbags (see sangar). There is also an intermediate branch known as semipermanent fortification. This is employed when in the course of a campaign it becomes desirable to protect some locality with the best imitation of permanent defences that can be made in a short time, ample resources and skilled civilian labor being available.

Castles are fortifications which are regarded as being distinct from the generic fort or fortress in that it describes a residence of a monarch or noble and commands a specific defensive territory.

History

Ancient

From very early history to modern times, walls have been a near necessity for every city. Uruk in ancient Sumer (Mesopotamia) is one of the world's oldest known walled cities. Before that, the city (or rather proto-city) of Jericho in what is now the West Bank had a wall surrounding it as early as the 8th millennium BC.

The Assyrians deployed large labour forces to build new palaces, temples and defensive walls.[1]

Some settlements in the Indus Valley Civilization were also fortified. By about 3500 B.C., hundreds of small farming villages dotted the Indus floodplain. Many of these settlements had fortifications and planned streets. The stone and mud brick houses of Kot Diji were clustered behind massive stone flood dykes and defensive walls, for neighboring communities quarreled constantly about the control of prime agricultural land.[2] Mundigak (c. 2500 B.C.) in present day south-east Afghanistan has defensive walls and square bastions of sun dried bricks.[3]

Exceptions were few — notably, ancient Sparta and ancient Rome did not have walls for a long time, choosing to rely on their militaries for defense instead. Initially, these fortifications were simple constructions of wood and earth, which were later replaced by mixed constructions of stones piled on top of each other without mortar.

In Central Europe, the Celts built large fortified settlements known as oppida, whose walls seem partially influenced by those built in the Mediterranean. The fortifications were continuously expanded and improved.

In ancient Greece, large stone walls had been built in Mycenaean Greece, such as the ancient site of Mycenae (famous for the huge stone blocks of its 'cyclopean' walls). In classical era Greece, the city of Athens built a long set of parallel stone walls called the Long Walls that reached their guarded seaport at Piraeus.

Large tempered earth (ie. rammed earth) walls were built in ancient China since the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600-1050 BC), as the capital at ancient Ao had enormous walls built in this fashion (see siege for more info). Although stone walls were built in China during the Warring States (481-221 BC), mass conversion to stone architecture did not begin in earnest until the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD). In terms of China's longest and most impressive fortification, the Great Wall had been built since the Qin Dynasty (221-207 BC), although its present form was mostly an engineering feat and remodeling of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 AD) during the 15th and 16th centuries. The large walls of Pingyao serve as one example. Likewise, the famous walls of the Forbidden City in Beijing were established in the early 15th century by the Yongle Emperor.

The Romans fortified their cities with massive, mortar-bound stone walls. The most famous of these are the largely extant Aurelian Walls of Rome and the Theodosian Walls of Constantinople, together with partial remains elsewhere. These are mostly city gates, like the Porta Nigra in Trier or Newport Arch in Lincoln.

Hadrian's Wall was built in built by the Roman Empire across the width of what is now northern England following a visit by Roman Emperor Hadrian (AD 76–138) in AD 122.

Medieval

Roman forts and hill forts were the main antecedents of castles in Europe, which emerged in the 9th century in the Carolingian Empire.

The Early Middle Ages saw the creation of some towns built around castles. These cities were only rarely protected by simple stone walls and more usually by a combination of both walls and ditches. From the 12th century AD hundreds of settlements of all sizes were founded all across Europe, which very often obtained the right of fortification soon afterwards.

The founding of urban centers was an important means of territorial expansion and many cities, especially in eastern Europe, were founded precisely for this purpose during the period of Eastern Colonisation. These cities are easy to recognise due to their regular layout and large market spaces. The fortifications of these settlements were continuously improved to reflect the current level of military development.

During the Renaissance era, the Venetians raised great walls around cities threatened by the Ottoman empire. The finest examples are, among others, in Nicosia (Cyprus) and Chania (Crete), and they still stand, to this day.

Early Modern

Medieval-style fortifications were largely made obsolete by the arrival of cannons on the 14th century battlefield. Fortifications in the age of blackpowder evolved into much lower structures with greater use of ditches and earth ramparts that would absorb and disperse the energy of cannon fire. Walls exposed to direct cannon fire were very vulnerable, so were sunk into ditches fronted by earth slopes.

This placed a heavy emphasis on the geometry of the fortification to allow defensive cannonry interlocking fields of fire to cover all approaches to the lower and thus more vulnerable walls. Fortifications also extended in depth, with protected batteries for defensive cannonry, to allow them to engage attacking cannon to keep them at a distance and prevent them bearing directly on the vulnerable walls. The result was star shaped fortifications with tier upon tier of hornworks and bastions, of which Bourtange illustrated to the right is an excellent example. There are also extensive fortifications from this era in the Nordic states and in Britain, the fortifications of Berwick-upon-Tweed being a fine example.

19th Century

The arrival of explosive shells in the nineteenth century led to yet another stage in the evolution of fortification. Star forts of the cannon era did not fare well against the effects of high explosive and the intricate arrangements of bastions, flanking batteries and the carefully constructed lines of fire for the defending cannon could be rapidly disrupted by explosive shells. Worse, the large open ditches surrounding forts of this type were an integral part of the defensive scheme, as was the covered way at the edge of the counter scarp. The ditch was extremely vulnerable to bombardment with explosive shells.

In response, military engineers evolved the polygonal style of fortification. The ditch became deep and vertically sided, cut directly into the native rock or soil, laid out as a series of straight lines creating the central fortified area that gives this style of fortification its name.

Wide enough to be an impassable barrier for attacking troops, but narrow enough to be a difficult target for enemy shellfire, the ditch was swept by fire from defensive blockhouses set in the ditch as well as firing positions cut into the outer face of the ditch itself.

The profile of the fort became very low indeed, surrounded outside the ditch by a gently sloping open area so as to eliminate possible cover for enemy forces, while the fort itself provided a minimal target for enemy fire. The entrypoint became a sunken gatehouse in the inner face of the ditch, reached by a curving ramp that gave access to the gate via a rolling bridge that could be withdrawn into the gatehouse.

Much of the fort moved underground, with deep passages and tunnels to connect the blockhouses and firing points in the ditch to the fort proper, with magazines and machine rooms deep under the surface.

The guns however, were often mounted in open emplacements and protected only by a parapet - both in order to keep a lower profile and also because experience with guns in closed casemates had seen them put out of action by rubble as their own casemates were collapsed around them.

20th Century

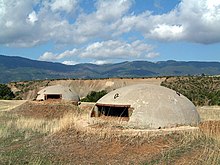

Steel-and-concrete fortifications were common during the 19th and early 20th centuries, however the advances in modern warfare since World War I have made large-scale fortifications obsolete in most situations. Only underground bunkers are still able to provide some protection in modern wars. Many historical fortifications were demolished during the modern age, but a considerable number survive as popular tourist destinations and prominent local landmarks today.

The downfall of permanent fortifications had three causes:

- The ever escalating power of artillery and air power meant that almost any target that could be located could be destroyed, if sufficient force was massed against it. As such, the more resources a defender devoted to reinforcing a fortification, the more combat power that fortification justified being devoted to destroying it, if the fortification's destruction was demanded by an attacker's strategy.

- The second weakness of permanent fortification was its very permanency. Because of this it was often easier to go around a fortification, and with the rise of mobile warfare in the beginning of World War II this became a viable offensive choice. When a defensive line was too extensive to be entirely bypassed, massive offensive might could be massed against one part of the line allowing a breakthrough, after which the rest of the line could be bypassed. Such was the fate of the many defensive lines built before and during World War II, such as the Maginot Line, the Siegfried Line, the Stalin Line and the Atlantic Wall. (In the case of the Atlantic Wall, the purpose of the fortification was to delay an invasion to allow reinforcement.)

- The third weakness is that modern firepower has progressed far beyond the strength of permanent fortifications, as a simple artillery or bombing barrage can easily destroy the most complex modern fortification. It is also much easier and cheaper to produce those modern siege weapons than to build any kind of fortification.

Instead field fortification rose to dominate defensive action. Unlike the trench warfare which dominated World War I these defenses were more temporary in nature. This was an advantage because since it was less extensive it formed a less obvious target for enemy force to be directed against. If sufficient power was massed against one point to penetrate it, the forces based there could be withdrawn and the line could be re-established relatively quickly. Instead of a supposedly impenetrable defensive line, such fortifications emphasized defense in depth, so that as defenders were forced to pull back or were over-run, the lines of defenders behind them could take over the defense.

Because the mobile offensives practiced by both sides usually focused on avoiding the strongest points of a defensive line, these defenses were usually relatively thin and spread along the length of a line. The defense was usually not equally strong throughout however. The strength of the defensive line in an area varied according to how rapidly an attacking force could progress in the terrain that was being defended - both the terrain the defensive line was built on and the ground behind it that an attacker might hope to break out into. This was both for reasons of the strategic value of the ground, and its defensive value.

This was possible because while offensive tactics were focused on mobility, so were defensive tactics. The dug in defenses consisted primarily of infantry and antitank guns. Defending tanks and tank destroyers would be concentrated in mobile "fire brigades" behind the defensive line. If a major offensive was launched against a point in the line, mobile reinforcements would be sent to reinforce that part of the line that was in danger of failing. Thus the defensive line could be relatively thin because the bulk of the fighting power of the defenders was not concentrated in the line itself but rather in the mobile reserves. A notable exception to this rule was seen in the defensive lines at the Battle of Kursk during World War II, where German forces deliberately attacked into the strongest part of the Soviet defenses seeking to crush them utterly.

The terrain that was being defended was of primary importance because open terrain that tanks could move over quickly made possible rapid advances into the defenders' rear areas that were very dangerous to the defenders. Thus such terrain had to be defended at all cost. In addition, since in theory the defensive line only had to hold out long enough for mobile reserves to reinforce it, terrain that did not permit rapid advance could be held more weakly because the enemy's advance into it would be slower, giving the defenders more time to reinforce that point in the line. For example the battle of the Hurtgen Forest in Germany during the closing stages of World War II is an excellent example of how impassable terrain could be used to the defenders' advantage.

Modern usage

Forts in modern usage often refer to space set aside by governments for a permanent military facility; these often do not have any actual fortifications, and can have specializations (military barracks, administration, medical facilities, or intelligence). In the United States usage, forts specifically refer to Army fortifications; Marine Corps fortifications are referred to as camps.

However there are some modern fortifications that are referred to as forts. These are typically small semi permanent fortifications. In urban combat they are built by upgrading existing structures such as houses or public buildings. In field warfare they are often log, sandbag or gabion type construction. Such forts are typically only used in low level conflict, e.g., counterinsurgency conflicts or very low level conventional conflicts, e.g., the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation saw the use of log forts for use by forward platoons and companies. The reason for this is that static above ground forts can not survive modern direct or indirect fire weapons larger than mortars, RPGs and small arms.

See also

Fort components

- Abatis

- Banquette

- Barbed wire, Razor wire, Wire entanglement, and Wire obstacle

- Bastion

- Berm

- Caponier

- Casemate

- Curtain

- Czech hedgehog

- Defensive fighting position (aka a "foxhole")

- Ditch

- Embrasure

- Glacis

- Gun turret

- Parapet

- Pillbox

- Postern

- Ravelin

- Revetment

- Sandbag

- Scarp and Counterscarp

- Turret

Types of forts and fortification

- Bastion fortress

- Blockhouse

- Bunker

- Castle

- City wall

- Chinese city wall

- Compound

- Flak tower

- Grad, a Slavic wooden fortified settlement

- Hill fort

- Land battery

- Martello tower

- Keep

- Martello tower

- Medieval fortification

- Pā a 19th-century Māori fortification

- Peel tower

- Polygonal fort

- Promontory fort

- Redoubt

- Stockade

- Star fort

Historical Fortresses

- Chittorgarh Fort

- Atlantic Wall

- Bastle house

- Beaumaris Castle

- Fort Knox, Maine

- Great Wall of China

- Walls of Constantinople

- Krak des Chevaliers

- Kremlin

- Lahore Fort

- Rohtas Fort

- Gibraltar

- Lines of Torres Vedras

- Maginot Line

- Massada

- Raigad Fort

- Norwegian Fortresses

- Eastbourne Redoubt

- Fort Drum (El Fraile Island)

- Mannerheim Line

- Reduit

- Fort Monroe

Fortification and siege warfare

Famous experts

- Mozi

- Fritz Todt

- Henri Alexis Brialmont

- James of St. George

- Menno van Coehoorn

- César Cui

- Diades of Pella

- Vauban

External links

- Fort 4a in Poznan - Poland

- 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica on Fortifications and siegecraft

- Fort Mifflin: Active American Revolution to Korean War, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA

- Information on Australian World War 2 Fortifications

- A Military History of Malta (Fortifications)

- Fortress Cologne

- Bunker Pictures: Pictures, locations, information about bunkers from WW2 and The Atlantikwall

- Royal Engineers Museum Coastal Defence

- Aerial photography: Fortress - Komárom - Hungary

- Petrovaradin - Greatest XVIII century fortress in Europe

- Redoubt Fortress Museum

- Eastbourne Redoubt

- Photos of Austrian, French and English castles

- Photos and History of the Peter and Paul (St Petersburg) Fortress

- Maginot Line at War

- German World War II Field Fortifications on the Eastern Front, Album of Drawings

- WW2 Fortifications in Greece

- 20th century Fortifications in Switzerland

- Fortification Walls of Vaste, Lecce, Italy

References

- ^ Banister Fletcher's A History of Architecture By Banister Fletcher, Sir, Dan Cruickshank, Dan Cruickhank, Sir Banister Fletcher. Published 1996 Architectural Press. Architecture. 1696 pages. ISBN 0750622679. pg no 20

- ^ The Encyclopedia of World History: ancient, medieval, and modern, chronologically arranged By Peter N. Stearns, William Leonard Langer. Compiled by William L Langer. Published 2001 Houghton Mifflin Books. History / General History. ISBN 0395652375. pg 17

- ^ Banister Fletcher's A History of Architecture By Banister Fletcher, Sir, Dan Cruickshank, Dan Cruickhank, Sir Banister Fletcher. Published 1996 Architectural Press. Architecture. 1696 pages. ISBN 0750622679. pg no 100

- ^ Albania's Chemical Cache Raises Fears About Others — Washington Post, Monday 10 January 2005, Page A01.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)