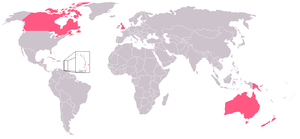

Australia–New Zealand relations

| |

Australia |

New Zealand |

|---|---|

The relationship between Australia and New Zealand is somewhat similar to that of other neighbouring countries with a shared British colonial heritage, such as Canada and the United States. Some have defined the relationship as less one of friendship than of brotherhood, beset by sibling rivalry.[1] Trans-Tasman relations is often used as a shorthand expression for the relationship between the two countries, since they are separated by the Tasman Sea.[2][3][4]

Relations between the two countries have been tense at times over relatively minor matters, such as sporting competitions involving rugby or cricket (for instance, the underarm delivery incident[5]), or commerce between the two countries (for example, Australia's anger over the Air New Zealand/Ansett Airlines fiasco[6]).

Despite this, relations between Australia and New Zealand are exceptionally close on both the national and interpersonal scales.[7] Former New Zealand Prime Minister Mike Moore declared that Australians and New Zealanders have more in common than New Yorkers and Californians.[8] Relations are especially close given the number of tourists that travel between the two countries and the (generally) common economics policy. Immigration, employment, and residency policies are also very liberal and generous between citizens of either nation, similar to a two-nation model European Union.

History

The modern nations of Australia and New Zealand are descended from British settler colonies established in the Australasian region in the 18th and 19th centuries. Although New Zealanders like to emphasise that their country was never a penal colony, neither were all the Australian colonies. In particular, South Australia was founded and settled in a similar manner to New Zealand, both being influenced by the ideas of Edward Gibbon Wakefield.[9] Both Australia and New Zealand experienced ongoing conflict with the indigenous populations - although this conflict took very different forms - and experienced nineteenth century gold rushes. During the nineteenth century there was extensive trade and travel between the colonies.[10]

While the colonies of Australia were federated together in 1901 as the Commonwealth of Australia, the more isolated colony of New Zealand developed into a separate dominion and eventually an independent country of its own; New Zealand was invited to join the Federation but declined. Although the two countries continued to co-operate politically, both sought closer relations with Britain, particularly in the area of trade. This was helped by the development of refrigerated shipping, which allowed New Zealand in particular to base its economy on the export of meat and dairy (both of which Australia had in abundance) to Britain.

In the 1908 London Olympics and the 1912 Stockholm Olympics Australia and New Zealand were represented by a unified team named "Australasia". In the precursor to the Empire (later Commonwealth) Games, the 1911 London "Festival of Empire", both Australia and New Zealand also fielded a unified Australasian team.

The quantity of trans-Tasman trade has increased by 9% per annum since the early 1980s[11], with the Closer Economic Relations free trade agreement of 1983 being a major turning point. This was partially a result of Britain joining the European Economic Community in the early 1970s, thus restricting the access of both countries to their biggest export market.

Relationships

Military

In the early twentieth century, both countries were enthusiastic members of the British Empire and both sent soldiers to the Boer War, First World War and Second World War and to a lesser extent the Korean War and Vietnam War.

In the First World War, the soldiers of both countries were formed into the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZACs). Together Australia and New Zealand saw their first major military action in the Battle of Gallipoli, in which both (along with other allied nations) suffered major casualties. For many decades the battle was seen by both countries as the moment at which they came of age as nations[12][13]. It continues to be commemorated annually in both countries on Anzac Day, although since the 1960s there has been some questioning of the 'coming of age' idea[citation needed]. Despite this, Anzac Day has attracted increased numbers in recent years, in both Australia and New Zealand.

World War Two was a major turning point for both countries, as they realised that they could no longer rely on the protection of Britain[14]. Australia was particularly struck by this realisation, as it came close to being invaded by Japan, and the city of Darwin was bombed and when Broome was attacked. Subsequently, both countries sought closer ties with the United States. This resulted in the ANZUS pact of 1951, in which Australia, New Zealand and the United States agreed to defend each other in the event of enemy attack. Although no such attack occurred until (arguably) September 11 2001, New Zealand and Australia both contributed troops to the Korean and Vietnam Wars. Australia's contribution to the Vietnam War in particular was much larger than New Zealand's; while Australia introduced conscription,[15] New Zealand sent only a token force.[16] Australia has continued to be more committed to the American alliance, ANZUS, than New Zealand; although both countries felt considerable unease about American military policy in the 1980s, New Zealand angered the United States by refusing port access to nuclear ships from 1985 and in retaliation, the United States 'suspended' its obligations under the ANZUS treaty to New Zealand.[17] Australia has made a significant contribution to the Iraq War, while New Zealand's much smaller military contribution was limited to UN-authorised reconstruction tasks.[18]

In 2001 the Australia-New Zealand Memorial was opened by the prime ministers of both countries on ANZAC Parade, Canberra. The memorial commemorates the shared effort to achieve common goals in both peace and war.[19]

ANZAC Bridge in Sydney was given its current name on Remembrance Day in 1998 to honour the memory of the soldiers of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) served in World War I. An Australian Flag flies atop the eastern pylon and a New Zealand Flag flies atop the western pylon. A bronze memorial statue of an Australian ANZAC soldier ("digger") holding a Lee Enfield rifle pointing down was placed on the western end of the bridge on ANZAC Day in 2000. A statue of a New Zealand soldier was added to a plinth across the road from the Australian Digger, facing towards the east, and unveiled by Prime Minister of New Zealand Helen Clark in the presence of Premier of New South Wales Morris Iemma on Sunday 27 April 2008.[20]

Migration

Many people have emigrated from New Zealand to Australia, including the former Premier of Queensland, Joh Bjelke-Petersen, the Premier of South Australia, Mike Rann, comedian turned psychologist Pamela Stephenson and actor Russell Crowe. Australians who have emigrated to New Zealand include the 17th and 23rd Prime Ministers of New Zealand Sir Joseph Ward and Michael Savage, Russel Norman, co-leader of the Green Party, and Matt Robson, deputy leader of the Progressive Party.[21]

From 1973 the Trans-Tasman Travel Arrangement, an informal agreement between Australia and New Zealand, has allowed for the free movement of citizens of one nation to the other. The only major exception to these travel privileges is for individuals with outstanding warrants or criminal backgrounds who are deemed dangerous or undesirable for the migrant nation and its citizens.

In recent decades, many New Zealanders have migrated to Australian cities such as Sydney, Brisbane, Melbourne and Perth.[22] The Trans-Tasman Travel Arrangement of 1973 means that, unlike citizens of other countries, New Zealand passport holders are issued with 'special category' visas on arrival in Australia, which allow them to live and work there. Although this agreement is reciprocal, and many people have migrated in each direction, there has been significant net migration from New Zealand to Australia.[23] In 2001 there were eight times more New Zealanders living in Australia than Australians living in New Zealand.[24] Many of these New Zealanders are Maori Australians.

Consequently, 'Kiwis' in Australia are accused of taking local jobs or living on Australian social welfare benefits, although since 2001, New Zealanders must now wait two years before they are eligible for such payments.[25] There are complaints in New Zealand that there is a brain drain to Australia.[26]

New Zealand Ministry of Education figures show the number of Australians at New Zealand tertiary institutions almost doubled from 1978 students in 1999 to 3916 in 2003. In 2004 more than 2700 Australians received student loans and 1220 a student allowance. Unlike other overseas students, Australians pay the same fees for higher education as New Zealanders and are eligible for student loans and allowances. New Zealand students are not treated on the same basis as Australian students in Australia.[27]

Persons born in New Zealand continue to be the second largest source of immigration to Australia, representing 11% of total permanent additions in 2005–06 and accounting for 2.3% of Australia's population at June 2006.[28]

Trading links

New Zealand's economic ties with Australia are strong, especially since the demise of Britain as a trading partner following its decision to join the then European Economic Community in 1973, and in the 1980s, the two countries concluded the Closer Economic Relations agreement, allowing each country access to the other's markets.

In 2005 and 2006 the Australian House of Representatives Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs inquired into the harmonisation of legal systems within Australia, and with New Zealand, with particular reference to those differences that have an impact on trade and commerce.[29] The Committee stated that the already close relationship between Australia and New Zealand should be closer still and that 'In this era of globalisation, it makes sense for Australia and New Zealand to look at moving closer together and further aligning their regulatory frameworks'. Key recommendations on the Australia-New Zealand relationship included:

- Establishment of a trans-Tasman parliamentary committee to monitor legal harmonisation and examine options including closer association or union;

- Pursuit of a common currency;

- Offering New Zealand Ministers full membership of Australian ministerial councils;

- Work to advance harmonisation of the two banking and telecommunications regulation frameworks.[30]

However, there are some trading issues between the countries, for example over the importation of apples. Australia has restricted the import of apples from New Zealand owing to Australian growers' fears of introducing fire blight disease. A ban on importation of New Zealand apples into Australia has been in place since 1921, following the discovery of fire blight in New Zealand in 1919. New Zealand authorities applied for re-admittance to the Australian market in 1986, 1989 and 1995, but the ban continued.[31] In 2002, the United States filed an action with the World Trade Organisation (WTO) against Japan's restrictions on apple imports; New Zealand and Australia both joined the case as third parties.[32] After the WTO Compliance Panel ruled in favour of the U.S. in 2003 and again in 2005,[33] Japan opened its market to U.S. apples.[34] Further talks over Australia's import restrictions on apples from New Zealand failed, and New Zealand initiated WTO dispute resolution proceedings in 2007.[35][36]

Political union

The 1901 Australian Constitution included provisions to allow New Zealand to join Australia as its seventh state, even after the government of New Zealand had already decided against such a move.[37] Section 6 of the Preamble declares that:

'The States' shall mean such of the colonies of New South Wales, New Zealand, Queensland, Tasmania, Victoria, Western Australia, and South Australia, including the northern territory of South Australia, as for the time being are parts of the Commonwealth, and such colonies or territories as may be admitted into or established by the Commonwealth as States; and each of such parts of the Commonwealth shall be called 'a State'.

One of the reasons that New Zealand chose not to join Australia was due to perceptions that the indigenous Māori population would suffer as a result.[38] At the time of Federation, Australia had a strict White Australia policy and indigenous Australians were not granted citizenship and the vote as early as the Māori in New Zealand, who had full citizenship, and universal suffrage since 1893.

Māori people had voting rights in Australia since 1902 as a result of the Commonwealth Franchise Act 1902, part of the effort to allay New Zealand's concerns about joining the Federation.[39] Indigenous Australians did not have the vote until 1962. During the parliamentary debates over the Act, King O'Malley supported the inclusion of Māori, and the exclusion of Australian Aboriginals, in the franchise, arguing that "An aboriginal is not as intelligent as a Maori."[40]

From time to time the idea of joining Australia has been mooted, but has been ridiculed by some New Zealanders. When Australia's former Liberal party leader, John Hewson, raised the issue in 2000, New Zealand's Prime Minister Helen Clark remarked that he could "dream on".[41] A 2001 book by Australian academic Bob Catley, then at the University of Otago, titled Waltzing with Matilda: should New Zealand join Australia?, was described by New Zealand political commentator Colin James as "a book for Australians".[42]

Unlike Canadians and Americans, who share a land border, New Zealand and Australia are more than 1920 km (1200 miles) apart, comparable with the distance from England to Africa. Arguing against Australian statehood, New Zealand's Premier, Sir John Hall, remarked that there were "1200 reasons" not to join the federation.[1]

Both countries have contributed to the sporadic discussion on a Pacific Union, although that proposal would include a much wider range of member-states than just Australia and New Zealand.

While there is no prospect of political union now, there is still a great deal of similarity between the two cultures, with the differences often only obvious to Australians and New Zealanders themselves. However, in 2006 there was a recommendation from an Australian federal parliamentary committee that a full union should occur or Australia and New Zealand should at least have a single currency and more common markets.[43] New Zealand Government submissions to that committee concerning harmonisation of legal systems however noted

Differences between the legal systems of Australia and New Zealand are not a problem in themselves. The existence of such differences is the inevitable product of well-functioning democratic decision-making processes in each country, which reflect the preferences of stakeholders, and their effective voice in the law-making process.[44]

Membership of international organizations

New Zealand and Australia are exclusive members of a collection of five countries who participate in the highly secretive ECHELON program. Other joint defence arrangements between New Zealand and Australia include the Five Power Defence Arrangements and ANZUS.

Similarities

Australia and New Zealand are both prosperous western democracies, and constitutional monarchies (with the same monarch) situated in the Oceania region. Both countries are members of the Commonwealth of Nations, a voluntary association of 53 independent sovereign states, most of which are former British colonies.

New Zealand and Australia are characterised by political stability, relatively high incomes, egalitarian cultures, low levels of corruption, and a long tradition of representative democracy. Both cultures have high rates of home ownership[45] and value leisure time, especially sports and other outdoor pursuits[citation needed]. Although originally dominated by an Anglo-Celtic culture, both countries have become increasingly multi-cultural in the latter decades of the 20th century.

Differences

Founding settlers

Most of the colonies that later became Australia were set up as convict settlements, whilst New Zealand was settled by free settlers. The European population of Australia from early times contained a large Irish Catholic minority, many of whom were hostile to the British overclass, in comparison to New Zealand which was largely settled by English and Scots loyal to the British Crown. This resulted in some significant differences in attitude to authority; New Zealand never had an equivalent to the Eureka Stockade[citation needed] revolt, and republicanism has been less of an issue than in Australia. In this respect, as well as in stereotypes (see below), the differences between New Zealand and Australia resemble those between Canada and the United States, respectively.

Indigenous relations

Since the beginning of European settlement, one of the major differences between Australia and New Zealand has been in the area of race relations. In part, this originated with the very different cultures of Māori and Indigenous Australians. When Europeans arrived, Australian Aboriginal culture was ancient and had been more or less unchanged for centuries, while Māori culture was relatively young. This was perhaps the reason why Indigenous Australians showed no interest in European goods and were thus reluctant to trade or otherwise co-operate with Europeans[citation needed], while Māori enthusiastically adopted many European goods and ideas (including Christianity)[46]. As a result, Māori were seen as intelligent and capable of civilisation, whereas Aborigines were widely seen as primitive and unable to learn.[47] One result of this is that Māori gained voting rights in Australia six decades before Indigenous Australians (and indeed before any other non-white group). As James Belich points out, it was not the case that white New Zealanders were less racist than white Australians, but rather that Māori were seen by both groups as superior to most other 'coloured' peoples.[48]

Another difference was in the nature of early settlement. The first European settlements in Australia were penal colonies, and the brutality of these inevitably impacted on the indigenous population[citation needed]. The country was claimed by Britain by 'right of discovery' and was officially 'terra nullius' (empty land) – a term which did not deny the existence of Aborigines but did deny their right to the land. In New Zealand, by contrast, some of the earliest settlers were missionaries who sought to convert Māori and protect them from less moral settlers[49]. By 1840, when the British Crown took possession of New Zealand, humanitarianism was a major force in Britain[citation needed]. This led to the creation of the Treaty of Waitangi, which transferred sovereignty from Māori to the Crown but also recognised Māori rights to their land and other properties and gave them the rights of British citizens. Although the Treaty was more or less ignored for most of the next 150 years, it did provide an important precedent, and would enable Māori to gain reparations and cultural recognition in the late twentieth century.

In both countries, there was major conflict between the races for much of the nineteenth century. In Australia this mainly took the form of skirmishes and raids, and was not widely considered to be a 'war'. In New Zealand, by contrast, much of the conflict involved armies and actual battles, which Māori won often enough to be considered as serious opponents. The participation by some Māori groups on the British side of the wars gained them several concessions from the colonial government, the most important being the four Māori seats in parliament.[citation needed] The wars also helped Māori unity and co-operation; the lack of a shared language made this difficult for Aborigines to achieve.[citation needed] However both peoples became an under-class in the nineteenth century: suffering discrimination, losing much of their land, and going into population decline. Disease and alcohol abuse became problems for both.[citation needed] Both populations recovered during the 20th century, although Māori now constitute a much larger proportion of the total New Zealand population (14.6% in 2006)[50] than Aborigines do in Australia (2.6% in 2006).[51] (Another 73,000 people of Māori descent lived in Australia in 2006,[52] compared to less than 500 Australian Aborigines in New Zealand.)[53]

Male Māori land owners in New Zealand were allowed to vote from 1852, all Māori men from 1868, and full suffrage was granted to all Māori including women, from 1893. In contrast, the situation in Australia was quite different. In 1901, the Constitution of Australia granted Aborigines the right to vote in Federal elections if their state granted them that right, however in practice that right was often illegally withheld from them. Australian Aborigines did not obtain universal suffrage until 1962, In some Australian states like New South Wales, Victoria & South Australia, Aborigines were allowed to vote thus they were allowed to vote at federal elections, while this has been denied by state governments in Queensland & Western Australia.

From those times, both groups established political movements aimed at regaining lost land, restoring culture and cultural pride, and educating the populace about their past[citation needed]. The Māori protest movement has been more successful than that of the Aborigines, mostly due to the Treaty of Waitangi. However, the Australian High Court decisions of Mabo and Wik have been important in Australia, ushering in the new doctrine of native title, and abolishing the old concept that Australia had been terra nullius (unoccupied land) at the time of European settlement.

Today there is a greater acceptance of the Māori culture in New Zealand than there is of the Aboriginal culture in Australia. The Māori language is taught in many schools in New Zealand whereas the teaching of any of the hundreds of Indigenous languages is quite rare in Australia due to the many languages that vary by different tribes. The haka, a traditional Māori dance, is performed by both Māori and non-Māori in the All Blacks. Whilst in earlier years a "kangaroo dance" was performed in reply by the Wallabies, it drew on no genuine part of Indigenous culture; in its place is often a rendition of "Waltzing Matilda", an iconic Australian song.

References

Sources

- Irving, Helen (1999). The Centenary Companion to Australian Federation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521573149.

- King, Michael (2003). The Penguin History of New Zealand. New Zealand: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780143018674.

- Mein Smith, Philippa (2005). A Concise History of New Zealand. Australia: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521542286.

Citations

- ^ a b Moldofsky, Leora (2001-04-30). "Friends, Not Family: It's time for a new maturity in the trans-Tasman relationship". Time Magazine. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- ^ Australia-New Zealand Closer Economic Relations 20 years Anniversay - Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

- ^ Celebration of Trans-Tasman Relations - Media Releases from the Australian Minister for Foreign Affairs

- ^ Speeches: Trans-Tasman Relations: A Securities Regulator's View | Securities Commission

- ^ Swanton, Will (2006-01-23). "25 years along, Kiwi bat sees funnier side of it". Cricket. The Age. Retrieved 2006-06-27.

- ^ Donovan, Paul (2002-05-09). "Air New Zealand - speech by Paul Donovan, Vice President Australia, to key Melbourne Travel Industry Executives". ASIA Travel Tips.com. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

... Air New Zealand was seriously affected by the maintenance groundings of Ansett's Boeing 767s, and the eventual collapse of the carrier - which was not just our Australian subsidiary but our Australian partner. Everybody in this room will have an opinion about the Ansett crisis, and it is not my intention today to try to change your perceptions of the past. I also understand that those opinions will be stronger in this State [Victoria, Australia] than in any other, as this was not only the home of Ansett but the birthplace of the airline.

- ^ "NZ, Australia 'should consider merger'". Sydney Morning Herald. 2006-12-04. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

The House of Representatives Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs [found] "While Australia and New Zealand are of course two sovereign nations, it seems to the committee that the strong ties between the two countries - the economic, cultural, migration, defence, governmental and people-to-people linkages - suggest that an even closer relationship, including the possibility of union, is both desirable and realistic,"

- ^ Australia and New Zealand Cooks - Community - Allrecipes

- ^ Wakefield's influence on the new Zealand Company: "Wakefield and the New Zealand Company". Early Christchurch. Christchurch City Libraries. Retrieved 2008-03-21. and in relation to Wakefield's connection with South Australia: "Edward Gibbon Wakefield". The Foundation of South Australia 1800-1851. State Library of South Australia. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

- ^ There were shipping connections between relatively minor ports and New Zealand, for example "the schooner Huia, which carried hardwood from Grafton on the north coast of New South Wales to New Zealand ports and softwoods in the other direction until about 1940." + "Trans-Tasman passenger shipping operated as an extension of the Australian interstate services, most intensively between Sydney and Wellington, but also connecting other Australian and New Zealand ports. Most of the Australian coastal shipping companies were involved in the trans-Tasman trade at some stage" per Deborah Bird Rose. (2003). "Chapter 2: Ports and Shipping, 1788-1970". Linking a Nation: Australia's Transport and Communications 1788 - 1970. Australian Heritage Commission. ISBN 0 642 23561 9.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) Also illustrating the point are the many wrecks of the Union Steam Ship Company "scattered around New Zealand, Australia and the South Pacific, but nowhere more thickly than in Tasmania and the dangerous bar harbours of Greymouth and Westport" per McLean, Gavin. "Union Steam Ship Company - History & Photos". NZ Marine History. New Zealand Ship and Marine Society. Retrieved 2008-03-20. - ^ "New Zealand Country Brief - January 2008". Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-21.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Mercer, Phil (25 April 2002). "Australians march in honour of Gallipoli". BBC News.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Clarke, Dr Stephen. "History of ANZAC Day". Royal New Zealand Returned and Services' Association.

- ^ Bowen, George (1997, 1999, 2000, 2001) [1997]. "4". [www.pearsoned.co.nz Defending New Zealand]. Auckland, New Zealand: Addison Wesley Longman. p. 12. ISBN 0 582 73940 3.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help); Check date values in:|year=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|accessyear=,|origmonth=,|accessmonth=,|month=,|chapterurl=,|origdate=, and|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Langford, Sue. "Encyclopedia - Appendix: The national service scheme, 1964-72". Australian War Memorial.

- ^ Rabel, Robert (1999). ""We cannot afford to be left too far behind Australia": New Zealand's entry into the Vietnam War in May 1965". Journal of the Australian War Memorial (32).

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "ANZUS Alliance". h2g2 edited guide. BBC. 2005-11-08. Retrieved 2008-04-22.

- ^ FAQs Re Light Engineer Group To Iraq, New Zealand Defence Force press release, 23 September 2004.

- ^ "Other Monuments and Sites - New Zealand Memorial, Canberra". Historic Graves and Monuments. New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 2008-04-24.

- ^ Samandar, Lema (2008-04-27). "Kiwi joins his little mate on Anzac Bridge watch". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2008-04-29.

- ^ Bingham, Eugene (2006-05-13). "No longer a 'foreign' minister". New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- ^ "Kiwis overseas - Migration to Australia". Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ^ Chapman, Paul (2006-05-13). "New Zealand warned over exodus to Australia". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- ^ Carl Walrond. Kiwis overseas - Migration to Australia, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 9 April 2008. Retrieved 26 January 2009.

- ^ "Welfare Payments To Be Restricted For Kiwis In Australia". ABC. 2001-02-26. Retrieved 2006-06-27.

- ^ Mahne, Christian (2002-07-24). "New Zealand voters fear brain drain". Business. BBC. Retrieved 2006-06-27.

- ^ Ross, Tara (2005-02-07). "NZ foots bill for Aussie students". The Age. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

- ^ "Migration: permanent additions to Australia's population". 4102.0 - Australian Social Trends, 2007. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2007-08-07. Retrieved 2008-05-30.

- ^ House Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs (2006-12-04). "Harmonisation of legal systems Within Australia and between Australia and New Zealand". Australian House of Representatives. Retrieved 2008-04-21.

- ^ "Report on Legal Harmonisation Tabled" (PDF) (Press release). Peter Slipper, MP, Chairman of the House of Representatives Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee. 4 December 2006. Retrieved 2008-04-21.

- ^ "The Proposed Importation of Fresh Apple Fruit from New Zealand: Chapter three - The Apple and Pear Industries in Australia and New Zealand" (pdf). Australian Senate - Senate Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport Committee. 2001-07-18. Retrieved 2008-03-26.

- ^ "WTO disputes with New Zealand a third party complainant - Japan - Measures Affecting the Importation of Apples (WT/DS245)". New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. 2007-07-19. Retrieved 2008-04-20.

- ^ "WTO ruling message for Australia". New Zealand Government. 2005-06-24. Retrieved 2008-04-20.

- ^ "Japan Ends Import Restrictions on Import of U.S. Apples". U.S. State Department. 2005-09-01. Retrieved 2008-04-20.

- ^ "NZ to take Australia to WTO over apple access". New Zealand Government press release. 2007-08-20. Retrieved 2008-04-20.

- ^ "Prime Minister Kevin Rudd offends apple growers; Australia: Apple pie jokes not funny for growers". Freshplaza.com ("an independent news source for companies operating in the global fruit and vegetable sector around the world") Netherlands. 2008-03-05. Retrieved 2008-03-26.

- ^ Why New Zealand Did Not Become An Australian State

- ^ "Why New Zealand Did Not Become An Australian State". 2005-04-27. Retrieved 2007-09-23.

- ^ The 1891 draft of the Australian Constitution specified that "aboriginal native(s)" would not be counted as part of the population. It was argued that this "would have resulted in New Zealand's having one less seat in the House of Representatives than if Maori were counted in the New Zealand population." Irving (1999), pg 403.

- ^ Commonwealth Franchise Bill, second reading. Australian House of Representatives Hansard. Retrieved on July 30, 2007.

- ^ "New Zealand scoffs at statehood idea". BBC. 2002-07-24. Retrieved 2006-06-27.

- ^ James, Colin (2001-07-24). "How not to waltz Matilda". Colin James. Retrieved 2006-06-27.

- ^ Dick, Tim (2006-12-05). "Push for union with New Zealand". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

Australia and New Zealand should work towards a full union, or at least have a single currency and more common markets, a federal parliamentary committee says

- ^ NZG, Submission No. 23, pp. 2, 6. to House Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs (4 December 2006). "Chapter 2 Basis and mechanisms for the harmonisation of legal systems". Harmonisation of legal systems Within Australia and between Australia and New Zealand. Australian House of Representatives. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Street, Maryan (2008-02-20). "Home ownership - protecting the Kiwi dream: Speech to Nelson Chamber of Commerce outlining the government's comprehensive action plan to improve the supply of affordable housing". Speeches by the Hon Maryan Street, Minister for Housing. New Zealand Government. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

Home ownership rates have fallen from 74 per cent to 67 per cent between 1991 and 2006. ...

Also note Atterhög, Mikael (2005). "Importance of government policies for home ownership rates: An international survey and analysis" (pdf (34 pages)). Section for Building and Real Estate Economics, Department of Real Estate and Construction Management, School of Architecture and the Built Environment, Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm. Retrieved 2008-03-20.Only Australia and New Zealand have had a negative development of the home ownership rate during the selected period [1960-2003] but the change was below one percentage point. From Table 2: Australian rate in 2001 was 67.8% and NZ was 68%

- ^ Sutherland, Ivan Lorin George, 1935. The Maori Situation. Harry H. Tombs, Wellington.

- ^ Australia - Aborigines And European Settlers

- ^ James Belich, Paradise Reforged.

- ^ Missionaries and the British Annexation of New Zealand « Beastrabban’s Weblog

- ^ "Māori Ethnic Population / Te Momo Iwi Māori". QuickStats About Māori, Census 2006. Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 2007-03-21.

- ^ 4705.0 - Population Distribution, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, 2006, Australian Bureau of Statistics. Accessed 9 December 2008.

- ^ Table 2.1, p 12, in Australian Bureau of Statistics (2004). Template:PDFlink. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Catalogue Number 2054.0.

- ^ Classification counts - Ethnic group, 2006 Census, Statistics New Zealand. Accessed 9 December 2008.