History of Mexico

This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (March 2009) |

| History of Mexico |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

Mexico is a country in North America and the largest Spanish-speaking country in the world. It also has the largest number of native Americans language speakers on the continent (the majority speaking Nahuatl, Mayan, Mixtec and Zapotec). For thousands of years, what is now known as Mexico was a land of hunter-gatherers. Around 9,000 years ago, ancient Amerindians domesticated corn and initiated an agricultural revolution, leading to the formation of many complex civilizations. These civilizations revolved around cities with writing, monumental architecture, astronomical studies, mathematics, and militaries. After 4,000 years, these civilizations were destroyed with the arrival of the Spaniards in 1519. For three centuries, Mexico was colonized by Spain, during which time the majority of its indigenous population died off. Formal independence from Spain was recognized in 1821. A war with the United States ended with Mexico losing almost half of its territory in 1848. France then invaded Mexico in 1861 and ruled briefly until 1867. The Mexican Revolution would later result in the death of 10% of the nation's population. Since then, Mexico as a nation-state has struggled with reconciling its deeply-entrenched indigenous heritage with the demands of the modern Western cultural model imposed in 1519. The nation's name is derived from the Aztec's capital called Mexico-Tenochtitlan.

Pre-Columbian civilizations

The pre-Columbian history of what now is known as Mexico is known through the work of archaeologists and epigraphers, and through the accounts of the conquistadors, clergymen, and indigenous chroniclers of the immediate post-conquest period. While relatively few parchments (or codices) of the Mixtec and Aztec cultures of the Post-Classic period survived the Spanish conquest, more progress has been made in the area of Mayan archaeology and epigraphy.[1]

Human presence in Mesoamerica was once thought to date back 40,000 years based upon what were believed to be ancient human footprints in the Valley of Mexico, but after further investigation using radioactive dating, it appears this may be untrue.[2] It is currently unclear whether 21,000 year old campfire remains found in the Valley of Mexico are the earliest human remains in Mexico.[3] Indigenous peoples began to selectively breed maize plants around 8,000 BC. Evidence shows a marked increase in pottery working by 2300 BC and the beginning of intensive corn farming between 1800 and 1500 BC.

Between 1800 and 300 BC, complex cultures began to form. Many matured into advanced pre-Columbian Mesoamerican civilizations such as the: Olmec, Izapa, Teotihuacan, Maya, Zapotec, Mixtec, Huastec, Tarascan, "Toltec" and Aztec, which flourished for nearly 4,000 years before the first contact with Europeans.

These civilizations are credited with many inventions and advancements including pyramid-temples, mathematics, astronomy, medicine, and theology.

While many city-states, kingdoms, and empires competed with one another for power and prestige, Mexico can be said to have had five major civilizations: The Olmec, Teotihuacan, the Toltec, the Aztec and the Maya. These civilizations (with the exception of the politically-fragmented Maya) extended their reach across Mexico, and beyond, like no others. They consolidated power and distributed influence in matters of trade, art, politics, technology, and theology. Other regional power players made economic and political alliances with these five civilizations over the span of 3,000 years. Many made war with them. But almost all found themselves within these five spheres of influence.

Latecomers to Mexico's central plateau, the Aztecs thought of themselves as heirs to the prestigious civilizations that had preceded them, much as Charlemagne did with respect to the fallen Roman Empire. What the Aztecs lacked in political power, they made up for with ambition and military skill.

In 1428, the Aztecs led a war of liberation against their rulers from the city of Azcapotzalco, which had subjugated most of the Valley of Mexico's peoples. The revolt was successful, and the Aztecs, through cunning political maneuvers and ferocious fighting skills, became the rulers of central Mexico as the leaders of the Triple Alliance.

This Alliance was composed of the city-states of Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan. At their peak, 350,000 Aztecs presided over a wealthy tribute-empire comprising around 10 million people, almost half of Mexico's then-estimated population of 24 million. This empire stretched from ocean to ocean, and extended into Central America. The westward expansion of the empire was halted by a devastating military defeat at the hands of the Purepecha (who possessed superior weapons made of copper). The empire relied upon a system of taxation (of goods and services) which were collected through an elaborate bureaucracy of tax collectors, courts, civil servants, and local officials who were installed as loyalists to the Triple Alliance (led by Tenochtitlan).

By 1519, the Aztec capital, Mexico-Tenochtitlan, was the largest city in the world with a population of around 350,000 (although some estimates range as high as 500,000). By comparison, the population of London in 1519 was 80,000 people. Tenochtitlan is the site of modern-day Mexico City.

Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire

In 1519, the Aztec civilization of what now is known as Mexico was invaded by Spain, and two years later in 1521, the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan was conquered by an alliance between Spanish and Tlaxcaltecs (the main enemies of Aztecs). Francisco Hernández de Córdoba explored the shores of South Mexico in 1517, followed by Juan de Grijalva in 1518. The most important of the early Conquistadores was Hernán Cortés, who entered the country in 1519 from a native coastal town which he renamed "Puerto de la Villa Rica de la Vera Cruz" (today's Veracruz).

Contrary to popular opinion, Spain did not conquer all the empire when Cortes conquered Tenochtitlan in 1521. It would take another two centuries after the Siege of Tenochtitlan before the Conquest of the Aztec Empire would be complete, as rebellions, attacks, and wars continued against the Spanish by other native peoples.

Role of religion in the fall of the Aztec Empire

The Aztecs' religious beliefs were based on a great fear that the universe would cease functioning without a constant offering of human sacrifice. They sacrificed thousands of people on special occasions. This belief is thought to have been common throughout Nahuatl people. In order to acquire captives in times of peace, the Aztec resorted to a form of "ritual warfare", or flower war. Tlaxcalteca and other Nahuatl nations were forced into such wars, and, not particularly liking the idea of being a perpetual source of human sacrifices, they willingly joined the Spaniard forces against the Aztecs. The small Spanish force, consisting of 508 men schooled in European warfare and equipped with steel weapons and armor, was reinforced with thousands of indigenous Indian allies. Their use of ambush during indigenous ceremonies allowed the Spanish to avoid fighting the best native warriors in direct armed battle, such as during The Feast of Huitzilopochtli.

The colonial period

The Spanish defeat of the Aztecs in 1521 marked the beginning of the 300 year-long colonial period called the New Spain. After the fall of Tenochtitlan, it would take decades of sporadic warfare to pacify the rest of Mesoamerica. Particularly fierce was the Chichimeca War in the north of the New Spain (1576-1606).

The Council of Indies and the Mendecant establishments that arose in Mesoamerica as early as 1524 labored to generate capital for the broken crown of Spain and convert the Indian populations to Catholicism. Over the period of conquest (1519-c1600s) and the following Colonial periods the sponsorship of Mendecant friars and a process of religious syncretism combined the Pre-Hispanic cultures with Spanish socio-religious tradition. The resulting hodgepodge of culture was a pluriethnic State that relied on the repartimiento of peasant "Republic of Indians" labor to accomplish any work considered necessary. The existing feudal system of pre-Hispanic Mesoamerican culture was replaced by the encomienda feudal-style system of Spain, probably adapted to the pre-Hispanic tradition. It was finally replaced by a debt-based inscription of labor that led to wide-spread revitalization movements and prompted the revolution that ended the colonial state of New Spain.

During the colonial period, which lasted from 1521 to 1810, Mexico was known as "la Nueva España" or "New Spain" (as aforementioned), whose territories included today's Mexico. ("Mexico" in this period only meant the area that is the Valley of Mexico.) This entity was part of an epoymous viceroyalty, which joined with it the Spanish Caribbean islands, Central America as far south as Costa Rica, the area comprising today's southwestern United States, and the Philippines. Since Spaniards conquered areas with high civilizations and dense populations, which could provide the settlers with a sufficient labor source and a population to catechize, Spaniards in the sixteenth century tended not to develop the territories that had nomadic peoples, which were harder to conquer (and in fact, with the exception of the Amazon Basin, were not subdued until the nineteenth century). The Spanish did explore a good part of North America looking for more treasure-laden societies. These explorers claimed the land as was their practice, but finding no treasures or sedentary Indian tribes, they returned to the areas in Mexico, which had already been conquered. It was not until the eighteenth century that a concerted effort was made to settle the northern frontier in what is now the United States. The end result is that a lot of historic and contemporary maps often misrepresent the areas Spain claimed as areas they actually controlled. The Indians who lived in these areas were out of reach of Hispanic society and were able to maintain their culture well into the nineteenth century.

Mexican war of independence

After Napoleon I invaded Spain in 1807 and put his brother, Joseph on the Spanish throne, Mexican Conservatives and rich land-owners who supported Spain's Bourbon royal family objected to the comparatively liberal Napoleonic policies. Thus an unlikely alliance was formed in Mexico: liberales, or Liberals, who favored a democratic Mexico, and conservadores, or Conservatives, who favored a Mexico ruled by a Bourbon monarch who would restore the status quo ante. These two elements agreed only that Mexico must achieve independence and determine her own destiny.

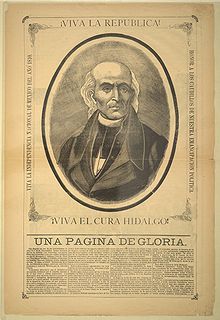

Taking advantage of the fact that Spain was severely handicapped under the occupation of Napoleon's army, Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, a Catholic priest of Spanish descent and progressive ideas, declared Mexico's independence from Spain in the small town of Dolores on September 16, 1810. This act started the long war, the first official document of independence was the Solemn Act of the Declaration of Independence of Northern America signed in 1813 by the Congress of Anáhuac.[4] Eventually led to the official recognition of independence from Spain in 1821 and the creation of the First Mexican Empire. As with many early leaders in the movement for Mexican independence, Hidalgo was captured by opposing forces and executed.

Prominent figures in Mexico's war for independence were Father José María Morelos, Vicente Guerrero, and General Agustín de Iturbide. The war for independence lasted eleven years until the troops of the liberating army entered Mexico City in 1821. Thus, although independence from Spain was first proclaimed in 1810, it was not achieved until 1821, by the Treaty of Córdoba, which was signed on August 24 in Córdoba, Veracruz, by the Spanish viceroy Juan de O'Donojú and Agustín de Iturbide, ratifying the Plan de Iguala.

In 1821, Agustín de Iturbide, a former Spanish general who switched sides to fight for Mexican independence, proclaimed himself emperor – officially as a temporary measure until a member of European royalty could be persuaded to become monarch of Mexico (see Mexican Empire for more information). A revolt against Iturbide in 1823 established the United Mexican States. In 1824, "Guadalupe Victoria" became the first president of the new country; his given name was actually Félix Fernández but he chose his new name for symbolic significance: Guadalupe to give thanks for the protection of Our Lady of Guadalupe, and Victoria, which means Victory.

After independence

After independence, several Spanish possessions in Central America which also proclaimed their independence were incorporated into Mexico from 1822 to 1823, with the exception of Chiapas and several other Central American states. The northern provinces grew increasingly isolated, economicaly and politically, due to prolonged Comanche raids and attacks. New Mexico in particular had been gravitating more toward Comancheria. In the 1820s, when the United States began to exert influence over the region, New Mexico had already begun to question its loyalty to Mexico City. By the time of the Mexican-American War large portions of northern Mexico had been systematically raided and pillaged by the Comanches, causing impoverishment, political fragmentation, and a general frustration with the inability, or unwillingness, of the Mexican government to curb the Comanches. [5]

Soon after achieving its independence from Spain, the Mexican government, in an effort to populate some of its sparsely-settled northern land claims, awarded extensive land grants in a remote area of the state of Coahuila y Tejas to thousands of immigrant families from the United States, on the condition that the settlers convert to Catholicism and assume Mexican citizenship. It also forbade the importation of slaves, a condition that, like the others, was largely ignored. A key factor in the decision to allow American to settle Texas was the hope that the immigrants would help buffer and protect the province from Comanche attacks. It was also hoped that the policy would blunt American imperial expansion by turning the immigrants into Mexican citizens. The policy failed on both accounts, as the Americans tended to settle far from the Comanche raiding zones and used the failure of the central Mexican government to suppress the raids as a pretext for declaring independence.[5]

First Republic

The government of the newly independent Mexico soon fell to rogue republican forces led by Antonio López de Santa Anna and others. The first Republic was formed with Guadalupe Victoria as its first president, followed in office by Vicente Guerrero who won the electoral vote but lost the popular vote. The Mexican constitution was at that time very similar to the US constitution; but was largely disregarded by the majority of the population. The conservative party saw the opportunity to control the government and led a revolution under the leadership of Gen. Anastasio Bustamante who became president from 1830 to early 1832. The federalists asked Gen. Antonio López de Santa Anna to overthrow Bustamante and he did, declaring General Manuel Gómez Pedraza (who won the electoral vote back in 1828) as the "true" president. Elections took place, and Santa Anna took office on 1832. Constantly changing political beliefs, as president (he was president eleven different times),[6] in 1834 Santa Anna abrogated the federal constitution, causing insurgencies in the southeastern state of Yucatán and the northernmost portion of the northern state of Coahuila y Tejas. Both areas sought independence from the central government. After negotiations and the presence of Santa Anna's army eventually brought Yucatán to again recognize Mexican sovereignty, Santa Anna's army turned to the northern rebellion. The inhabitants of Tejas, calling themselves Texans and led mainly by relatively recently-arrived English-speaking settlers, declared independence from Mexico at Washington-on-the-Brazos, giving birth to the Republic of Texas. Texan militias defeated the Mexican army and captured General Santa Anna at the Battle of San Jacinto. Texas declared their independence from Mexico in 1836, further reducing the claimed territory of the fledgling Mexican republic. In 1845, Texans voted to be annexed by the United States, and this was agreed to by the U.S. Congress and signed into law by President John Tyler.

War with the United States

Many presidents, dictators, etc. came and went during a long period of instability which lasted most of the 19th century. One of the dominant figures of the second quarter of that century was the dictator Antonio López de Santa Anna.

Santa Anna was Mexico's leader during the conflict with Texas, which declared itself independent from Mexico in 1836 and ensured that independence by defeating the Mexican army and Santa Anna. Santa Anna was in and out of power again during the U.S.-Mexican War (1846-48). After accepting Texas's application for statehood in 1846, the US government sent troops to Texas in order to secure the territory, subsequently ignoring Mexico's demands for US withdrawal. Mexico saw this as a US intervention in their internal affairs by supporting a rebel province.

Disagreements about boundaries made the conflict inevitable. Mexican troops then attacked and killed several American soldiers and captured a small American detachment between the Rio Grande (which the Republic of Texas, and subsequently the U.S., claimed as the southern border) and the Nueces River (which had been considered the historic southern border of the Mexican department of Tejas). As a result, President James K. Polk requested a declaration of war, and the US Congress voted in favor on May 13, 1846. Mexico formally declared war on 23 May. This resulted in the Mexican–American War, which lasted from 1846 to 1848. Mexico was defeated by United States forces, which occupied Mexico City and many other parts of the country. The war was terminated with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hildalgo which stipulated that, as a condition for peace, Mexico was obligated to sell the mostly vacant northern territories to the United States for US$15 million. Over the next few decades, Americans settled these territories and petitioned for statehood, forming the states of California, Nevada, and Utah, and most of Arizona, New Mexico, and Colorado. Baja California was not included in the U.S. purchases or in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hildalgo despite being occupied by U.S. troops at the end of the war.

The primary reason for Mexico's defeat was its problematic internal situation, which led to a lack of unity and organization for a successful defense. One of the very few commemorated groups of Mexicans in the U.S. invasion of 1847 was a group of very young Military College cadets (now considered by some as Mexican national heroes). These cadets fought to the death defending their college against a detachment of American soldiers during the Battle of Chapultepec (September 13, 1847). Another group of combatants revered by Mexicans was the Batallón de San Patricio, a unit composed of hundreds of mostly Irish-born American deserters who fought under Mexican command until their overwhelming defeat at the Battle of Churubusco (August 20, 1847). Most of the "San Patricios" were killed and a few captured. Many of the captured men were court-martialled by the U.S. Army as deserters and traitors, and were subsequently executed at Chapultepec.

In 1853, mostly vacant desert territory containing parts of present-day Arizona and New Mexico were sold to the United States in the Gadsden Purchase. This land was sold by President Santa Anna in order to gain personal profit and to pay off his army. The Americans had not realized when they were negotiating the Treaty of Hidalgo (when they accepted the Gila River as the southern U.S. boundary) that a much easier railroad route to California lay slightly south of the Gila River. The Southern Pacific Railroad, the second transcontinental railroad to California, was built through this purchased land in 1881. As a bonus, the city of Tucson (Arizona) and its few hundred inhabitants was added to the United States territory of New Mexico.

The struggle for liberal reforms

In 1855, Santa Anna, who had become leader one more time, was overthrown by the liberals, in what was called the Revolution of Ayutla. The moderate liberal Ignacio Comonfort became president. The Moderados tried to find a middle ground between the nation's Liberals and Conservatives.

The 1857 Constitution

During Comonfort's presidency, a new Constitution was drafted. The Constitution of 1857 retained most of the Roman Catholic Church's Colonial era privileges and revenues, but, unlike the earlier constitution, did not mandate that the Catholic Church be the nation's exclusive religion. Such reforms were unacceptable to the leadership of the clergy and the Conservatives. Comonfort and members of his administration were excommunicated, and a revolt was then declared.

The War of Reform

This led to the War of Reform, from December 1857 to January 1861. This civil war became increasingly bloody and polarized the nation's politics. Many of the Moderates came over to the side of the Liberals, convinced that the great political power of the Church needed to be curbed. For some time, the Liberals and Conservatives had their own governments, the Conservatives in Mexico City and the Liberals headquartered in Veracruz. The war ended with Liberal victory, and Liberal president Benito Juárez moved his administration to Mexico City.

French intervention and the Second Mexican Empire

In the 1860s, the country again underwent a military occupation, this time by France, establishing the Habsburg Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian of Austria on the throne of Mexico as Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico, with support from the Roman Catholic clergy and conservative elements of the upper class as well as some indigenous communities. Although the French, then considered one of the most efficient armies of the world, suffered an initial defeat in the Battle of Puebla on May 5, 1862 (now commemorated as the Cinco de Mayo holiday) they eventually defeated the Mexican government forces led by the general Ignacio Zaragoza and set the couple upon the throne.

The Mexican monarchy set up its government in the Capital of Mexico City and used the National Palace as their government seat. The Emperor's consort, born a Belgian princess, was Empress Carlota of Mexico, a cousin of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom. The Imperial couple chose as their home Chapultepec Castle, and later adopted two grandchildren of the first Mexican Emperor, Augustin I. The Imperial couple noticed how the people of Mexico were treated, especially the Indians, and wanted to ensure their human rights. They were interested in a Mexico for the Mexicans, and did not share the views of Napoleon III, who was interested in exploiting the rich mines in the north-west of the country.

Emperor Maximilian I favored the establishment of a limited monarchy sharing powers with a democratically elected congress. This was too liberal to please Mexico's Conservatives, while the liberals refused to accept a monarch, leaving Maximilian with few enthusiastic allies within Mexico. Maximilian was eventually captured and executed in the Cerro de las Campanas, Querétaro, by the forces loyal to President Benito Juárez, who kept the federal government functioning during the French intervention that put Maximilian in power.

In mid-1867, following repeated losses in battle to the Republican Army and ever decreasing support by Napoleon III, Maximilian was captured and executed by Juárez's soldiers, along with his last loyal generals, Mejia and Miramon in Querétaro. From then on, Juárez remained in office until his death from heart failure in 1872.

Restoration of the Republic

In 1867, the republic was restored and Juárez was reelected, continuing to implement his reforms. In 1871 he was elected a second time, much to the dismay of his opponents within the liberal party, who considered reelection to be something undemocratic. Juárez died one year later and was succeeded by Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada.

Order, progress and the Díaz dictatorship

In 1876 Lerdo was re-elected, defeating Porfirio Díaz in the elections. Díaz rebelled against the government with the proclamation of the Plan de Tuxtepec, in which he opposed reelection, in 1876. Díaz managed to overthrow Lerdo, who fled the country, and was named president.

Díaz became the new president. Thus began a period of more than thirty years (1876–1911) during which Díaz was the strong man in Mexico. This period of relative prosperity and peace is known as the Porfiriato. During this period, the country's infrastructure improved greatly thanks to increased foreign investment. However, the period is also characterized by social inequality and discontent among the working classes.

The Mexican Revolution

1910-1921

In 1910 the 80-year-old Díaz decided to hold an election to serve another term as president. He thought he had long since eliminated any serious opposition in Mexico; however, Francisco I. Madero, an academic from a rich family, decided to run against him and quickly gathered popular support, despite Díaz putting Madero in jail.

When the official election results were announced, it was declared that Díaz had won re-election almost unanimously, with Madero receiving only a few hundred votes in the entire country. This fraud by the Porfiriato was too blatant for the public to swallow, and riots broke out. Madero prepared a document known as the Plan de San Luis Potosí, in which he called the Mexican people to take their weapons and fight against the government of Porfirio Díaz on November 20, 1910. Madero managed to flee to San Antonio, Texas, where he started to prepare his overthrow of the Díaz government. This started what is known as the Mexican Revolution.

The Federal Army was defeated by the revolutionary forces which were led by, amongst others, Emiliano Zapata in the South, Pancho Villa and Pascual Orozco in the North, and Venustiano Carranza. Porfirio Díaz resigned in 1911 for the "sake of the peace of the nation" and went to exile in France, where he died in 1915.

The revolutionary leaders had many different objectives; revolutionary figures varied from liberals such as Madero to radicals such as Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa. As a consequence, it proved very difficult to reach agreement on how to organize the government that emanated from the triumphant revolutionary groups. The result of this was a struggle for the control of Mexico's government in a conflict that lasted more than twenty years. This period of struggle is usually referred to as part of the Mexican Revolution, although it might also be considered a civil war. Presidents Francisco I. Madero (1913), Venustiano Carranza (1920), and former revolutionary leaders Emiliano Zapata (1919) and Pancho Villa (1923) were assassinated during this time, amongst many others.

Following the resignation of Díaz and a brief reactionary interlude, Madero was elected President in 1911. He was ousted and killed in 1913 by Victoriano Huerta, with the support of the U.S. ambassador to Mexico, Henry Lane Wilson, but not that of U.S. President-elect Woodrow Wilson. Huerta was a former General of Porfirio Díaz. Huerta's brutality soon lost him his domestic support, and his regime was actively opposed by the Wilson Administration. In 1915 he was overthrown by Venustiano Carranza, a former revolutionary general. Carranza promulgated a new Constitution on February 5, 1917. The Mexican Constitution of 1917 still guides Mexico. Carranza was assassinated in an internal feud of his former supporters over who would replace him as President.

In 1920 Álvaro Obregón, one of Carranza's former allies who plotted against him, became president. He accommodated all elements of Mexican society except the most reactionary clergy and landlords, and successfully catalyzed social liberalization, particularly in curbing the role of the Catholic Church, improving education and taking steps toward instituting women's civil rights.

While the Mexican revolution and civil war may have subsided after 1920, armed conflicts did not cease. The most widespread conflict of this era was the battle between those favoring a secular society with separation of Church and State and those favoring supremacy of the Roman Catholic Church, which developed into an armed uprising by supporters of the Church that came to be called "la Guerra Cristera."

It is estimated that between 1910 and 1921 about 900,000 people died.

The Cristero War 1926-1929

Between 1926 and 1929 an armed conflict in the form of a popular uprising broke out against the anti-Catholic/anti-clerical Mexican government, set off specifically by the anti-clerical provisions of the Mexican Constitution of 1917. Discontent over the provisions had been simmering for years. The conflict is known as the Cristero War. A number of articles of the 1917 Constitution were at issue. Article 5 outlawed monastic religious orders. Article 24 forbade public worship outside of church buildings, while Article 27 restricted religious organizations' rights to own property. Finally, Article 130 took away basic civil rights of members of the clergy: priests and religious leaders were prevented from wearing their habits, were denied the right to vote, and were not permitted to comment on public affairs in the press.

The Cristero War was eventually resolved diplomatically, largely with the influence of the U.S. Ambassador. The conflict claimed the lives of some 90,000: 56,882 on the federal side, 30,000 Cristeros, and numerous civilians and Cristeros who were killed in anticlerical raids after the war's end. As promised in the diplomatic resolution, the laws considered offensive to the Cristeros remained on the books, but no organized federal attempts to enforce them were put into action. Nonetheless, in several localities, persecution of Catholic priests continued based on local officials' interpretations of the law.[citation needed]

The Institutional Revolutionary Party

In 1929, the National Mexican Party (PNM) was formed by the serving president, General Plutarco Elías Calles. (It would later become the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) that ruled the country for the rest of the 20th century.) The PNM succeeded in convincing most of the remaining revolutionary generals to dissolve their personal armies to create the Mexican Army, and so its foundation is considered by some the real end of the Mexican Revolution.

The PRI set up a new type of system, led by a caudillo.

The PRI is typically referred to as the three-legged stool, in reference to Mexican workers, peasants and bureaucrats.

After it was founded in 1929, the PRI monopolized all the political branches. The PRI did not lose a senate seat until 1988 or a gubernatorial race until 1989.[7] It wasn't until July 2, 2000, that Vicente Fox of the opposition "Alliance for Change" coalition, headed by the National Action Party (PAN), was elected president. His victory ended the Institutional Revolutionary Party's 71-year hold on the presidency.

President Lázaro Cárdenas

President Lázaro Cárdenas came to power in 1935 and transformed Mexico. On April 1, 1936 he exiled Calles, the last general with dictatorial ambitions, thereby removing the army from power.

Cárdenas managed to unite the different forces in the PRI and set the rules that allowed his party to rule unchallenged for decades to come without internal fights. He nationalized the oil industry on March 18, 1938, the electricity industry, created the National Polytechnic Institute, granted asylum to Spanish expatriates fleeing the Spanish Civil War, started land reform and the distribution of free textbooks for children.

President Manuel Ávila Camacho

Manuel Ávila Camacho, Cárdenas's successor, presided over a "bridge" between the revolutionary era and the era of machine politics under PRI that would last until 2000. Camacho, moving away from nationalistic autarchy, proposed to create a favorable climate for international investment, favored nearly two generations ago by Madero. Camacho's regime froze wages, repressed strikes, and persecuted dissidents with a law prohibiting the "crime of social dissolution." During this period, the PRI regime thus betrayed the legacy of land reform. Miguel Alemán Valdés, Camacho's successor, even had Article 27 amended to protect elite landowners.

The Mexican economic miracle

During the next four decades, Mexico experienced impressive economic growth (from a very low base), and historians call this period "El Milagro Mexicano", the Mexican Miracle. This was in spite of failing foreign confidence in investment during the worldwide Great Depression. The assumption of mineral rights and subsequent nationalisation of the oil industry into Pemex during the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas del Río was a popular move.

Economy collapses

However, the economy collapsed several times afterwards. Although PRI regimes achieved economic growth and relative prosperity for almost three decades after World War II, the management of the economy collapsed several times, and political unrest grew in the late 1960s, culminating in the Tlatelolco massacre in 1968. In the 1970s, economic crises affected the country in 1976 and 1982, after which the banks were nationalized, having been blamed for the economic problems. (La Década Perdida) On both occasions, the Mexican peso was devalued, and, until 2000, it had been normal to expect a big devaluation and a recessionary period after each presidential term ended every six years. The crisis that came after a devaluation of the peso in late 1994 threw Mexico into economic turmoil, triggering the worst recession in over half a century.

1985 earthquake

On September 19, 1985, an earthquake measuring approximately 8.1 on the Richter scale struck Michoacán and inflicted severe damage on Mexico City. Estimates of the number of dead range from 6,500 to 30,000. (See 1985 Mexico City earthquake.)

NAFTA

On January 1, 1994, Mexico became a full member of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), joining the United States of America and Canada in a large and prosperous economic bloc. It is on this date that the Zapatista Army of National Liberation emerged, capturing several towns and sparking a brief conflict with the government. On March 23, 2005, the Security and Prosperity Partnership of North America was signed by the elected leaders of those countries.

According to the U.S. CIA Factbook for 2006: Mexico has a free market economy that recently entered the trillion dollar class. It contains a mixture of modern and outmoded industry and agriculture, increasingly dominated by the private sector. Recent administrations have expanded competition in seaports, railroads, telecommunications, electricity generation, natural gas distribution, and airports. Per capita income is one-fourth that of the US; income distribution remains highly unequal. Trade with the US and Canada has tripled since the implementation of NAFTA in 1994. Mexico has 12 free trade agreements with over 40 countries including, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, the European Free Trade Area, and Japan, putting more than 90% of trade under free trade agreements.

The Fox administration was cognizant of the need to upgrade infrastructure, modernize the tax system and labor laws, and allow private investment in the energy sector, but has been unable to win the support of the opposition-led Congress. The current Calderón government that took office in December 2006 is confronting the same challenges of boosting economic growth, improving Mexico's international competitiveness, and reducing poverty.

The end of PRI's hegemony

Accused many times of blatant fraud, the PRI's candidates continually held almost all public offices until the end of the 20th century. It was not until the 1980s that the PRI lost the first state governorship, an event that marked the beginning of the party's loss of hegemony. Through the electoral reforms started by president Carlos Salinas de Gortari and consolidated by president Ernesto Zedillo, by the mid 1990s, the PRI had lost its majority in Congress. In 2000, after seventy years, the PRI lost a presidential elections to a candidate of the National Action Party (PAN — Partido Acciòn Nacional), Vicente Fox. He was the 69th president of Mexico. The continued non-PAN majority in the Congress of Mexico prevented him from implementing most of his reforms.

President Ernesto Zedillo

In 1995, President Ernesto Zedillo faced an economic crisis. There were public demonstrations in Mexico City and constant military presence after the 1994 rising of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation in Chiapas. Zedillo also oversaw political and electoral reforms that reduced the PRI's hold on power. After the 1988 election, which was strongly disputed and arguably lost by the government party, the IFE (Instituto Federal Electoral – Federal Electoral Institute) was created in the early 1990s. It is run by ordinary citizens, overseeing that elections are conducted legally and fairly.

President Vicente Fox Quesada

As a result of popular discontent, the presidential candidate of the National Action Party (PAN) Vicente Fox Quesada won the federal election of July 2, 2000, but did not win a majority in the chambers of congress. The results of this election ended 71 years of PRI hegemony in the presidency. Many people in Mexico claim that, even if Fox won the election, President Zedillo did not give his party (PRI) a chance to dispute the results of the election by making Fox's victory "official" by addressing the nation the same night of the election, a first in Mexican politics (and in other places, too, where it is more normal for the losing candidate to admit defeat, rather than the outgoing incumbent). One reason offered for this is that Zedillo sought a quick and peaceful election in 2000 to avoid another crisis after the change of government.

President Felipe Calderón Hinojosa

Felipe Calderón Hinojosa (also a member of the conservative National Action Party (PAN) is, as of July 2006, the president of Mexico. Many people in Mexico claim that he actually did not win the election: as a result, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, the candidate of the leftist Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) appointed himself as the "legitimate president" and is currently traveling all over the country, along with his own cabinet, with resources from the taxes from all Mexicans, to strictly supervise every and all of the actions of president Felipe Calderón.

In 2008, there was a major escalation in the Mexican Drug War.

See also

Further reading

- Daily Life of the Aztecs, on the Eve of the Spanish Conquest , Jacques Soustelle, Stanford University Press, 1970, ISBN 0-8047-0721-9

- Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs, Michael Coe, Thames & Hudson, 2004, 5th edition, ISBN 0-500-28346-X

- 1491 : New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus, Charles Mann, Knopf, 2005, ISBN 1-4000-4006-X

- American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World, David Stannard, Oxford University Press, 1993, Rep edition, ISBN 0-19-508557-4

- Mexico Profundo, Guillermo Bonfil Batalla, University of Texas Press, 1996, ISBN 0-292-70843-2

- Mexico's Indigenous Past, Alfredo Lopez Austin, Leonardo Lopez Lujan, University of Oklahoma Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8061-3214-0

- American Indian Contributions to the World: 15,000 Years of Inventions and Innovations , Kay Marie Porterfield, Emory Dean Keoke, Checkmark Books, 2003, paperback edition, ISBN 0-8160-5367-7

- Great River, The Rio Grande in North American History, Paul Horgan, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, reprint, 1977, in one hardback volume, ISBN 0-03-029305-7

- An Archaeological Guide to Central and Southern Mexico, Joyce Kelly, University of Oklahoma Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8061-3349-X

- The Course of Mexican History , Michael C. Meyer, William L. Sherman, Susan M. Deeds, Oxford University Press, 2002, ISBN 0-19-514819-3

- Skywatchers : A Revised and Updated Version of Skywatchers of Ancient Mexico , Anthony Aveni, University of Texas Press, 2001, ISBN 0-292-70502-6

- The Olmecs: America's First Civilization, Richard A. Diehl, Thames & Hudson , 2004, ISBN 0-500-02119-8

- The Broken Spears: The Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico , Miguel Leon-Portillo, Beacon Press, 1992, ISBN 0-8070-5501-8

- Prehistoric Mesoamerica: Revised Edition, Richard E. W. Adams, University of Oklahoma Press, 1996, ISBN 0-8061-2834-8

- Michael Snodgrass, Deference and Defiance in Monterrey: Workers, Paternalism, and Revolution in Mexico, 1890-1950 (Cambridge University Press, 2003) (ISBN 0-521-81189-9)

- Borderlands/La Frontera, Gloria Anzaldua, Aunt Lute Books, San Francisco, 1987, ISBN 1-879960-56-7

Notes

- ^ Bakalar, Nicholas (2006-01-05). "Earliest Maya Writing Found in Guatemala, Researchers Say". National Geographic News. National Geographic Society. Retrieved 2009-04-18.

- ^ Paul R. Renne; et al. (2005). "Geochronology: Age of Mexican ash with alleged 'footprints'". Nature. 438: E7–E8. doi:10.1038/nature04425. PMID 16319838.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ "Native Americans", Encarta

- ^ This Declaration of Independence promised to maintain the Catholic religion and announced recovery of Mexico's "usurped sovereignty" under "the present circumstances in Europe" and "the inscrutable designs of Providence." Vazquez, Josefina Zoraida (March 1999) "The Mexican Declaration of Independence" The Journal of American History 85(4): pp. 1362-1369, p. 1368

- ^ a b Hämäläinen, Pekka (2008). The Comanche Empire. Yale University Press. pp. 357–358. ISBN 978-0-300-12654-9.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) Online at Google Books - ^ Scheina, Robert L. (2002) Santa Anna: a curse upon Mexico Brassey's, Washington D.C., ISBN 1-57488-405-0

- ^ "Mexico (The 1988 Elections)". Federal Research Division. June 1996. Retrieved 2009-04-18.

External links

- Hernán Cortés: Página de relación

- Brown University Library: Three for Three Million – Information about the Paul R. Dupee Jr. '65 Mexican History Collection in the John Hay Library, including maps and photos of books

- History of Mexico – Provides a history of Mexico from ancient times to today

- Mexico: From Empire to Revolution – Photographs from the Getty Research Institute's collections exploring Mexican history and culture though images produced between 1857 and 1923

- US-Mexican War – US political context and overview of military campaign that ended with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, 1816-1848. Provides links to US military sources

- Civilizations in America – Overview of Mexican civilization

- Time Line of Mexican History – A Pre-Columbian History time line and a time line of Mexico after the arrival of the Spanish