Holy Grail

According to Christian mythology, the Holy Grail was the dish, plate, or cup used by Jesus at the Last Supper, said to possess miraculous powers. The connection of Joseph of Arimathea with the Grail legend dates from Robert de Boron's Joseph d'Arimathie (late 12th century) in which Joseph receives the Grail from an apparition of Jesus and sends it with his followers to Great Britain; building upon this theme, later writers recounted how Joseph used the Grail to catch Christ's blood while interring him and that in Britain he founded a line of guardians to keep it safe. The quest for the Holy Grail makes up an important segment of the Arthurian cycle, appearing first in works by Chrétien de Troyes.[1] The legend may combine Christian lore with a Celtic myth of a cauldron endowed with special powers.

The development of the Grail legend has been traced in detail by cultural historians: It is a legend which first came together in the form of written romances, deriving perhaps from some pre-Christian folklore hints, in the later 12th and early 13th centuries. The early Grail romances centered on Percival and were woven into the more general Arthurian fabric. Some of the Grail legend is interwoven with legends of the Holy Chalice.

Origins

Grail

The Grail plays a different role everywhere it appears, but in most versions of the legend the hero must prove himself worthy to be in its presence. In the early tales, Percival's immaturity prevents him from fulfilling his destiny when he first encounters the Grail, and he must grow spiritually and mentally before he can locate it again. In later tellings the Grail is a symbol of God's grace, available to all but only fully realized by those who prepare themselves spiritually, like the saintly Galahad.

Early forms

There are two veins of thought concerning the Grail's origin. The first, championed by Roger Sherman Loomis, Alfred Nutt, and Jessie Weston, holds that it derived from early Celtic myth and folklore. Loomis traced a number of parallels between Medieval Welsh literature and Irish material and the Grail romances, including similarities between the Mabinogion's Bran the Blessed and the Arthurian Fisher King, and between Bran's life-restoring cauldron and the Grail. Other legends featured magical platters or dishes that symbolize otherworldly power or test the hero's worth. Sometimes the items generate a never-ending supply of food, sometimes they can raise the dead. Sometimes they decide who the next king should be, as only the true sovereign could hold them.

On the other hand, some scholars believe the Grail began as a purely Christian symbol. For example, Joseph Goering of the University of Toronto has identified sources for Grail imagery in 12th century wall paintings from churches in the Catalan Pyrenees (now mostly removed to the Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya, Barcelona), which present unique iconic images of the Virgin Mary holding a bowl that radiates tongues of fire, images that predate the first literary account by Chrétien de Troyes. Goering argues that they were the original inspiration for the Grail legend.[2][3]

Another recent theory holds that the earliest stories that cast the Grail in a Christian light were meant to promote the Roman Catholic sacrament of the Holy Communion. Although the practice of Holy Communion was first alluded to in the Christian Bible and defined by theologians in the first centuries AD, it was around the time of the appearance of the first Christianized Grail literature that the Roman church was beginning to add more ceremony and mysticism around this particular sacrament. Thus, the first Grail stories may have been celebrations of a renewal in this traditional sacrament.[4] This theory has some basis in the fact that the Grail legends are a phenomenon of the Western church (see below).

Most scholars today accept that both Christian and Celtic traditions contributed to the legend's development, though many of the early Celtic-based arguments are largely discredited (Loomis himself came to reject much of Weston and Nutt's work). The general view is that the central theme of the Grail is Christian, even when not explicitly religious, but that much of the setting and imagery of the early romances is drawn from Celtic material.

Etymology

The word grial, as it is earliest spelled, appears to be an Old French adaptation of the Latin gradalis, meaning a dish brought to the table in different stages of a meal. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, after the cycle of Grail romances was well established, late medieval writers came up with a false etymology for sangréal, an alternative name for "Holy Grail." In Old French, san graal or san gréal means "Holy Grail" and sang réal means "royal blood"; later writers played on this pun. Since then, "Sangreal" is sometimes employed to lend a medievalizing air in referring to the Holy Grail. This connection with royal blood bore fruit in a modern bestseller linking many historical conspiracy theories (see below).

Beginnings in literature

Chrétien de Troyes

The Grail is first featured in Perceval, le Conte du Graal (The Story of the Grail) by Chrétien de Troyes, who claims he was working from a source book given to him by his patron, Count Philip of Flanders. In this incomplete poem, dated sometime between 1180 and 1191, the object has not yet acquired the implications of holiness it would have in later works. While dining in the magical abode of the Fisher King, Perceval witnesses a wondrous procession in which youths carry magnificent objects from one chamber to another, passing before him at each course of the meal. First comes a young man carrying a bleeding lance, then two boys carrying candelabras. Finally, a beautiful young girl emerges bearing an elaborately decorated graal, or "grail."

Chrétien refers to his object not as "The Grail" but as un graal, showing the word was used, in its earliest literary context, as a common noun. For Chrétien the grail was a wide, somewhat deep dish or bowl, interesting because it contained not a pike, salmon or lamprey, as the audience may have expected for such a container, but a single Mass wafer which provided sustenance for the Fisher King’s crippled father. Perceval, who had been warned against talking too much, remains silent through all of this, and wakes up the next morning alone. He later learns that if he had asked the appropriate questions about what he saw, he would have healed his maimed host, much to his honor. The story of the Wounded King's mystical fasting is not unique; several saints were said to have lived without food besides communion, for instance Saint Catherine of Genoa. This may imply that Chrétien intended the Mass wafer to be the significant part of the ritual, and the Grail to be a mere prop.

Robert de Boron

Though Chrétien’s account is the earliest and most influential of all Grail texts, it was in the work of Robert de Boron that the Grail truly became the "Holy Grail" and assumed the form most familiar to modern readers. In his verse romance Joseph d’Arimathie, composed between 1191 and 1202, Robert tells the story of Joseph of Arimathea acquiring the chalice of the Last Supper to collect Christ’s blood upon His removal from the cross. Joseph is thrown in prison where Christ visits him and explains the mysteries of the blessed cup. Upon his release Joseph gathers his in-laws and other followers and travels to the west, and founds a dynasty of Grail keepers that eventually includes Perceval.

Other early literature

After this point, Grail literature divides into two classes. The first concerns King Arthur’s knights visiting the Grail castle or questing after the object; the second concerns the Grail’s history in the time of Joseph of Arimathea.

The nine most important works from the first group are:

- The Perceval of Chrétien de Troyes.

- Four continuations of Chrétien’s poem, by authors of differing vision and talent, designed to bring the story to a close.

- The German Parzival by Wolfram von Eschenbach, which adapted at least the holiness of Robert’s Grail into the framework of Chrétien’s story.

- The Didot Perceval, named after the manuscript’s former owner, and purportedly a prosification of Robert de Boron’s sequel to Joseph d’Arimathie.

- The Welsh romance Peredur, generally included in the Mabinogion, likely at least indirectly founded on Chrétien's poem but including very striking differences from it, preserving as it does elements of pre-Christian traditions such as the Celtic cult of the head.

- Perlesvaus, called the "least canonical" Grail romance because of its very different character.

- The German Diu Crône (The Crown), in which Gawain, rather than Perceval, achieves the Grail.

- The Lancelot section of the vast Vulgate Cycle, which introduces the new Grail hero, Galahad.

- The Queste del Saint Graal, another part of the Vulgate Cycle, concerning the adventures of Galahad and his achievement of the Grail.

Of the second class there are:

- Robert de Boron’s Joseph d’Arimathie,

- The Estoire del Saint Graal, the first part of the Vulgate Cycle (but written after Lancelot and the Queste), based on Robert’s tale but expanding it greatly with many new details.

Though all these works have their roots in Chrétien, several contain pieces of tradition not found in Chrétien which are possibly derived from earlier sources.

Conceptions of the Grail

The Grail was considered a bowl or dish when first described by Chrétien de Troyes. Other authors had their own ideas; Robert de Boron portrayed it as the vessel of the Last Supper, and Peredur had no Grail per se, presenting the hero instead with a platter containing his kinsman's bloody, severed head. In Parzival, Wolfram von Eschenbach, citing the authority of a certain (probably fictional) Kyot the Provençal, claimed the Grail was a stone that fell from Heaven (called lapsit exillis), and had been the sanctuary of the Neutral Angels who took neither side during Lucifer's rebellion. The authors of the Vulgate Cycle used the Grail as a symbol of divine grace. Galahad, illegitimate son of Lancelot and Elaine, the world's greatest knight and the Grail Bearer at the castle of Corbenic, is destined to achieve the Grail, his spiritual purity making him a greater warrior than even his illustrious father. Galahad and the interpretation of the Grail involving him were picked up in the 15th century by Sir Thomas Malory in Le Morte d'Arthur, and remain popular today.

Various notions of the Holy Grail are currently widespread in Western society (especially British, French and American), popularized through numerous medieval and modern works (see below) and linked with the predominantly Anglo-French (but also with some German influence) cycle of stories about King Arthur and his knights. Because of this wide distribution, Americans and West Europeans sometimes assume that the Grail idea is universally well known. The stories of the Grail are totally absent from the folklore of those countries that were and are Eastern Orthodox (whether Arabs, Slavs, Romanians, or Greeks). This is true of all Arthurian myths, which were not well known east of Germany until the present-day Hollywood retellings. Nor has the Grail been as popular a subject in some predominantly Catholic areas, such as Spain and Latin America, as it has been elsewhere. The notions of the Grail, its importance, and prominence, are a set of ideas that are essentially local and particular, being linked with Catholic or formerly Catholic locales, Celtic mythology and Anglo-French medieval storytelling. The contemporary wide distribution of these ideas is due to the huge influence of the pop culture of countries where the Grail Myth was prominent in the Middle Ages.

Later legend

Belief in the Grail and interest in its potential whereabouts has never ceased. Ownership has been attributed to various groups (including the Knights Templar, probably because they were at the peak of their influence around the time that Grail stories started circulating in the 12th and 13th centuries).

There are cups claimed to be the Grail in several churches, for instance the Saint Mary of Valencia Cathedral, which contains an artifact, the Holy Chalice, supposedly taken by Saint Peter to Rome in the first century, and then to Huesca in Spain by Saint Lawrence in the 3rd century. According to legend the monastery of San Juan de la Peña, located at the south-west of Jaca, in the province of Huesca, Spain, protected the chalice of the Last Supper from the Islamic invaders of the Iberian Peninsula. Archaeologists say the artifact is a 1st century Middle Eastern stone vessel, possibly from Antioch, Syria (now Turkey); its history can be traced to the 11th century, and it presently rests atop an ornate stem and base, made in the Medieval era of alabaster, gold, and gemstones. It was the official papal chalice for many popes, and has been used by many others, most recently by Pope Benedict XVI, on July 9, 2006.[5] The emerald chalice at Genoa, which was obtained during the Crusades at Caesarea Maritima at great cost, has been less championed as the Holy Grail since an accident on the road, while it was being returned from Paris after the fall of Napoleon, revealed that the emerald was green glass.

In Wolfram von Eschenbach's telling, the Grail was kept safe at the castle of Munsalvaesche (mons salvationis), entrusted to Titurel, the first Grail King. Some, not least the monks of Montserrat, have identified the castle with the real sanctuary of Montserrat in Catalonia, Spain. Other stories claim that the Grail is buried beneath Rosslyn Chapel or lies deep in the spring at Glastonbury Tor. Still other stories claim that a secret line of hereditary protectors keep the Grail, or that it was hidden by the Templars in Oak Island, Nova Scotia's famous "Money Pit", while local folklore in Accokeek, Maryland says that it was brought to the town by a closeted priest aboard Captain John Smith's ship. Turn of the century accounts state that Irish partisans of the Clan Dhuir (O'Dwyer, Dwyer) transported the Grail to the United States during the 19th Century and the Grail was kept by their descendents in secrecy in a small abbey in the upper-Northwest (now believed to be Southern Minnesota). [6]

Modern interpretations

Modern retellings

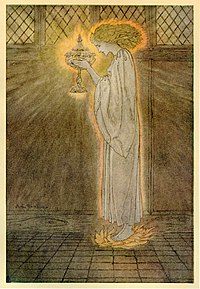

The story of the Grail and of the quest to find it became increasingly popular in the nineteenth century, referred to in literature such as Alfred Tennyson's Arthurian cycle the Idylls of the King. The combination of hushed reverence, chromatic harmonies and sexualized imagery in Richard Wagner's late opera Parsifal gave new significance to the grail theme, for the first time associating the grail – now periodically producing blood – directly with female fertility.[7] The high seriousness of the subject was also epitomized in Dante Gabriel Rossetti's painting (illustrated), in which a woman modelled by Jane Morris holds the Grail with one hand, while adopting a gesture of blessing with the other. Other artists, including George Frederic Watts and William Dyce also portrayed grail subjects.

The Grail later turned up in movies; it debuted in a silent Parsifal. In The Light of Faith (1922), Lon Chaney attempted to steal it, for the finest of reasons. The Silver Chalice, a novel about the Grail by Thomas B. Costain was made into a 1954 movie (in which Paul Newman debuted), that is considered notably bad by several critics, including Newman himself. Lancelot du Lac (1974) is Robert Bresson's gritty retelling. In vivid contrast, Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975) (adapted in 2004 as the stage production Spamalot) deflated all pseudo-Arthurian posturings. Excalibur attempted to restore a more traditional heroic representation of an Arthurian tale, in which the Grail is revealed as a mystical means to revitalise Arthur himself, and of the barren land to which his depressive sickness is connected. Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade and The Fisher King place the quest in modern settings, one a modern-day treasure hunt, the other robustly self-parodying.

The Grail has been used as a theme in fantasy, historical fiction and science fiction; a quest for the Grail appears in Bernard Cornwell's series of books The Grail Quest, set during The Hundred Years War. Michael Moorcock's fantasy novel The War Hound and the World's Pain depicts a supernatural Grail quest set in the era of the Thirty Years' War, and science fiction has taken the Quest into interstellar space, figuratively in Samuel R. Delany's 1968 novel Nova, and literally on the television shows Babylon 5 and Stargate SG-1 (as the "Sangraal"). Marion Zimmer Bradley's The Mists of Avalon has the grail as one of four objects symbolizing the four Elements: the Grail itself (water), the sword Excalibur (fire), a dish (earth), and a spear or wand (air). The grail features heavily in the novels of Peter David's Knight trilogy, which depict King Arthur reappearing in modern-day New York City, in particular the second and third novels, One Knight Only and Fall of Knight. The grail is central in many modern Arthurian works, including Charles Williams's novel War in Heaven and his two collections of poems about Taliessin, Taliessin Through Logres and Region of the Summer Stars, and in feminist author Rosalind Miles' Child of the Holy Grail. The Grail also features heavily in Umberto Eco's 2000 novel Baudolino. In King and Emperor, the final volume of Harry Harrison's 1990s trilogy The Hammer and the Cross, the name "grail" is explained to be a corruption of "graduale", Latin for ladder, and the Holy Grail is discovered, being the ladder which was used to remove Jesus' body from the cross and on which the body was carried away. The story further "reveals" that Jesus survived the crucification, and went on to live a life and father children, as well as writing a repressed Gospel. Fantasy and historical novelist Stephen R. Lawhead wrote a five-piece Arthurian epic in the 1980s and 90s entitled The Pendragon Cycle, followed by a related but stand-alone Arthurian novel, Avalon (1999), set in the near future of the twenty-first century.

Non-fiction

The Grail has also been treated in works of non-fiction, which generally seek to interpret its meaning in novel ways. Such a tack was taken by psychologists Emma Jung and Marie-Louise von Franz, who utilized analytical psychology to interpret the Grail as a series of symbols in their book The Grail Legend.[8] This type of interpretation had previously been utilized, in less detail, by Carl Jung, and was later invoked by Joseph Campbell.[8]

Other works, generally of dubious historical value, attempt to connect the Grail to conspiracy theories and esoteric traditions. In The Sign and the Seal, Graham Hancock asserts that the Grail story is a coded description of the stone tablets stored in the Ark of the Covenant. For the authors of Holy Blood, Holy Grail, who assert that their research ultimately reveals that Jesus may not have died on the cross, but lived to wed Mary Magdalene and father children whose Merovingian lineage continues today, the Grail is a mere sideshow: they say it is a reference to Mary Magdalene as the receptacle of Jesus' bloodline.[9][10]

Such works have been the inspiration for a number of popular modern fiction novels. The best known is Dan Brown's bestselling novel The Da Vinci Code, which, like Holy Blood, Holy Grail, is based on the idea that the real Grail is not a cup but the womb and later the earthly remains of Mary Magdalene (again cast as Jesus' wife), plus a set of ancient documents telling the "true" story of Jesus, his teachings and descendants. In Brown's novel, it is hinted that Jesus was merely a mortal man with strong ideals, and that the Grail was long buried beneath Rosslyn Chapel in Scotland, but that in recent decades its guardians had it relocated to a secret chamber embedded in the floor beneath the Inverted Pyramid near the Louvre Museum. The latter location, like Rosslyn Chapel, has never been mentioned in real Grail lore. Yet such was the public interest in this fictionalized Grail that for a while, the museum roped off the exact location mentioned by Brown, lest visitors inflict any damage in a more-or-less serious attempt to access the supposed hidden chamber

See also

- Cornucopia, sampo and the Cup of Jamshid are other mythical vessels with magical powers.

- Relics attributed to Jesus

- List of Mythological Objects

References

- ^ Loomis, Roger Sherman (1991). The Grail: From Celtic Myth to Christian Symbol. Princeton. ISBN 0-691-02075-2 [1]

- ^ Goering, Joseph (2005). The Virgin and the Grail: Origins of a Legend. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10661-0. [2]

- ^ Rynor, Micah (October 20, 2005). "Holy Grail legend may be tied to paintings". www.news.utoronto.ca.

- ^ Barber, Richard (2004). The Holy Grail: Imagination and Belief, Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01390-5. [3]

- ^ Glatz, Carol (July 10, 2006). "At Mass in Valencia, pope uses what tradition says is Holy Grail". Catholic News.

- ^ Wagner, Wilhelm, Romance and Epics of Our Northern Ancestors, Norse, Celt and Teuton, Norroena Society Publisher, New York, 1906.

- ^ Donington, Robert (1963). Wagner's "Ring" and its Symbols: the Music and the Myth. Faber

- ^ a b Barber, 248–252.

- ^ Baigent, Michael; Leigh, Richard; Lincoln, Henry (1983). Holy Blood, Holy Grail. New York: Dell. ISBN 0-440-13648-2

- ^ Juliette Wood, "The Holy Grail: From Romance Motif to Modern Genre", Folklore, Vol. 111, No. 2. (October 2000), pp. 169-190.

External links

- The Holy Grail at the Camelot Project

- The Holy Grail at the Catholic Encyclopedia

- The Holy Grail today in Valencia Cathedral

- The Holy Grail, an episode of In Our Time (BBC Radio 4), a 45 minute discussion is available for listening at the page.

- Template:Fr icon XVth century Old French Estoire del saint Graal manuscript BNF fr. 113 Bibliothèque Nationale de France, selection of illuminated folios, Modern French Translation, Commentaries.