Madison Square and Madison Square Park

40°44′31″N 73°59′17″W / 40.742054°N 73.987984°W

Madison Square is formed by the intersection of Fifth Avenue and Broadway at 23rd Street in the New York City borough of Manhattan. The square was named for James Madison, fourth President of the United States and the principal author of the American Constitution.[1]

The focus of the square is Madison Square Park, a 6.8 acre (2.75 hectare) public park, which is bounded on the east by Madison Avenue (which starts at the park's southeast corner at 23rd Street); on the south by 23rd Street; on the north by 26th Street; and on the west by Fifth Avenue and Broadway as they cross.

The park and the square are at the northern (uptown) end of the Flatiron District neighborhood of Manhattan. The use of "Madison Square" as a name for the neighborhood has fallen off, and it is rarely heard.

Madison Square is probably best known around the world for lending its name to Madison Square Garden, which was a sports arena located just northeast of the park until 1925. The current Madison Square Garden, the fourth such building, is not in the area. Notable buildings around Madison Square include the Flatiron Building, the Met Life Tower, and the New York Life Building. A new high-rise condominium tower, "One Madison Park", will rival the Met Life Tower in height.

Madison Square can be reached using local service on the R, W, and N lines of the subway at the 23rd Street and 28th Street Stations. In addition, local stops on the 6 and F and V lines are one block away at Park Avenue and Sixth Avenue, respectively.

Early New York

The area where Madison Square is now had been a swampy hunting ground, and first came into existence as a public space in 1686. In 1807, "The Parade", a tract of about 240 acres (97.12 hectares), was set aside for use as an arsenal, a barracks, and a potter's field. There was a United States Army arsenal there from 1811 until 1825 when it became the House of Refuge for the Society for the Protection of Juvenile Delinquents for children under sixteen committed by the courts for indefinite periods. It used the facility until 1839 when the building was destroyed by fire.[2][3][1] The size of the tract was reduced in 1814 to 90 acres (36.42 hectares), and it received its current name.

In 1839, a farmhouse located at what is now Fifth Avenue and 23rd Street was turned into a roadhouse under the direction of William "Corporal" Thompson (1807-1872), who renamed it later "Madison Cottage", after the former president. This house was the last stop for people travelling northward out of the city, or the first stop for those arriving from the north.

Though Madison Cottage itself was razed in 1853 to make room for the new Fifth Avenue Hotel,[4] Madison Cottage ultimately gave rise to the names for the adjacent avenue (Madison Avenue) and park — and thereby to Madison Square Gardens and Madison Racing, which remains an Olympic Sport today.

The roots of the New York Knickerbocker Base Ball Club, one of the first professional baseball teams ever, are in Madison Square. Amateur players began in 1842 to use a vacant sandlot at 27th and Madison for their games and, eventually, Alexander Cartwright suggested they draw up rules for the game and start a professional club. When they lost their sandlot to development, they moved to Hoboken, where they played their first game in 1846.[3][1]

The park opens

On May 10, 1847, Madison Square Park opened to the public. In 1853, plans were made to build the Crystal Palace there, but strong public opposition and protests caused the palace to be relocated to Bryant Park. From the 1850s to the 1870s the square was the center of an aristocratic neighborhood of brownstones, where Theodore Roosevelt, and Edith Wharton were born.[1].

The Fifth Avenue Hotel, a luxury hotel built by developer Amos Eno, and initially known as "Eno's Folly" because it was so far away from the hotel district, stood on the west side of Madison Square from 1859 to 1908. The first hotel in the city with elevators, which were steam-operated and known as the "vertical railroad", it had fireplaces in every bedroom, private bathrooms, and public rooms which saw many elegant events. Notable visitors to the hotel included Mark Twain, famed Swedish singer Jenny Lind, U.S. Presidents Chester A. Arthur and Ulysses S. Grant and the Prince of Wales.

With the success of the hotel, which could house 800 guests, other grand hotels such as the Hoffman House, the Brunswick and the Victoria, opened in the surrounding area, as did entertainment venues such as the Madison Square Theatre and Chickering Hall and many private clubs.[2] When the center of the expanding city moved north by the turn of the century, and the neighborhood had become a commercial district and was no longer fashionable, the hotel was closed and demolished. A plaque on the building current on the site, the Toy Center, commemorates the hotel.[1]

When the Draft Riots hit New York in 1863, ten thousand Federal troops brought in to control the rioters were bivuoacked in Madison Square and Washington Square, as well as Gramercy Park.[3]

Worth Square

At the northern end of Madison Square, on an island bordered by Broadway, Fifth Avenue and 25th Street, stands an obelisk, designed by James G. Batterson[5] which was erected in 1857 over the tomb of General William Jenkins Worth, who served in the Seminole Wars and the Mexican War,[1], and for whom Fort Worth, Texas was named, as well as Worth Street in lower Manhattan.[6]

The city's Parks Department designated the area immediately around the monument as a park called General Worth Square.[7]

Worth's monument was one of the first to be erected in a city park since the statue of George III was removed from Bowling Green in 1776,[8] and is the only monument in the city except for Grants Tomb that doubles as a mausoleum.

Renewal

Madison Square Park was relandscaped in 1870 by William Grant and Ignatz Pilat[5], a former assistant to Frederick Law Olmstead. The new design brought in the sculptures that now reside in the park. One notable sculpture is that of Secretary of State William H. Seward, which sits at the southwest entrance to the park. Seward, who is best remembered for purchasing Alaska ("Seward's Folly") from Russia, was the first New Yorker to have a monument erected in his honor.

Other statues in the park depict Roscoe Conkling, who served in Congress in both the House and the Senate; Chester Alan Arthur, the twenty-first President of the United States; and Admiral David Farragut, who is supposed to have said "Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead" in the Battle of Mobile Bay during the Civil War.

Other park highlights are an ornamental fountain added in 1867 and the Eternal Light Flagpole, dedicated on Armistice Day 1923 and restored in 2002, which commemorates the return of American soldiers and sailors from World War I.

In 1876 a large celebration was held in Madison Square Park to honor the centennial of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, and from 1876 to 1882, the torch and arm of the Statue of Liberty were exhibited in the park in an effort to raise funds for the building of the base of the statue.

Madison Square was the site of some of the first electric street lighting in the city. In 1879 the city authorized the Brush Electric Light Company to build a generating station at 25th Street, powered by steam, that provided electricity for a series of arc lights which were installed on Broadway between Union Square (at 14th Street) and Madison Square. The lights were illuminated on 20 December 1880. A year later, 160-foot (49 m) "sun towers" with clusters of arc lights were erected in Union and Madison Squares.[3]

In 1908 the New York Herald installed a giant searchlight among the girders of the Metropolitan Life Tower to signal election results. A northward beam signaled a win for the Republican candidate, and a southward beam for the Democrat. The beam went north, signalling the victory of Republican William Howard Taft.

America's first community Christmas tree was illuminated in Madison Square Park on December 24, 1912, an event which is commemorated by the Star of Hope, installed in 1916 at the southern end of the park. Today the Madison Square Park Conservancy continues to present an annual tree lighting ceremony sponsored by local businesses.

Author Willa Cather described the Madison Square around 1915: "Madison Square was then at the parting of the ways; had a double personality, half commercial, half social, with shops to the south and residences to the north. It seemed to me so neat, after the raggedness of our Western cities; so protected by good manners and courtesy – like an open-air drawing-room. I could well imagine a winter dancing party being given there, or a reception for some distinguished European visitor."[9]

Ceremonial Arches

To celebrate the centennial of George Washington's first inauguration, in 1889 two temporary arches were erected over Fifth Avenue and 23rd and 26th Streets. Just ten years later, in 1899, the Dewey Arch was built over Fifth Avenue and 24th Street at Madison Square for the parade in honor of Admiral George Dewey, celebrating his victory in the Battle of Manila Bay in the Philippines the year before. The arch was intended to be temporary, but remained in place until 1901 when efforts to have the arch rebuilt in stone failed, and it was demolished.

Fifteen years passed, and in 1918 Mayor John F. Hylan had a "Victory Arch" built at about the same location to honor the city's war dead. Thomas Hastings designed a triple arch which cost $80,000 and was modeled after the Arch of Constantine in Rome. Once again, a bid to make the arch permanent failed.[10]

Madison Square Garden

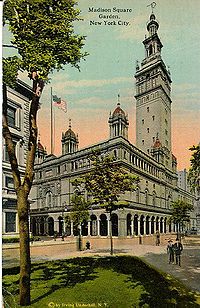

The building that became the first Madison Square Garden at 26th Street and Madison Avenue was originally the passenger depot of the New York and Harlem Railroad. When the depot moved uptown in 1871, the building was sold to P.T. Barnum who converted it into the "Hippodrome" for circus performances. In 1876 it became "Gilmore's Garden," an open air arena used for sporting events such as marathon races and, in 1877, the first Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show. It was finally renamed "Madison Square Garden" in 1879 by William Kissam Vanderbilt, who continued to present sporting events, the National Horse Show and boxing "exhibitions", since competitive boxing matches were illegal at the time. Vanderbilt eventually sold his "patched-up grumy, drafty combustible, old shell" to a syndicate that included J. P. Morgan, Andrew Carnegie, James Stillman and W. W. Astor.[3]

The building that replaced it was a Beaux-Arts structure designed by the noted architect Stanford White. White kept an apartment in the building, and was shot dead in the Garden's rooftop restaurant by millionaire Harry K. Thaw over an affair White had with Thaw's wife, the well-known actress Evelyn Nesbit, who White seduced when she was 16. The resulting sensational press coverage of the scandal caused Thaw's trial to be one of the first Trials of the Century.

Madison Square became known as "Diana's little wooded park" after the huge bronze statue of the Roman goddess Diana by Augustus Saint-Gaudens that stood atop the 32-story tower of White's arena – at the time it was the second-tallest building in the city.

The Garden hosted the annual French Ball, both the Barnum and the Ringling circuses, orchestral performances, light operas and romantic comedies, and the 1924 Democratic National Convention, which nominated John W. Davis after 103 ballots, but it was never a financial success.[3] It was torn down soon after, and the venue moved uptown. Today, the arena retains its name, even though it is no longer located in the area of Madison Square.

Modern period

In 1936, to commemorate the centennial of the opening of Madison Avenue, the Fifth Avenue Association donated a tree from the Virginia estate of former president James Madison. It is located toward the center of the eastern perimeter of the park.

In the 1960s, a plan to build a parking garage underneath the park was successfully blocked by preservationists, who cited concerns about the damage that the excavation would cause to the park, particularly the roots of its many trees.[11]

On October 17, 1966, a fire across the street from the park, at 7 East 23rd Street, resulted in the second most deadly building collapse in the history of the New York City Fire Department, when twelve firefighters – two chiefs, two lieutenants, and eight firefighters – were killed. A plaque honoring them can be seen on the building currently occupying the site, Madison Green.

Madison Square now

Having fallen into disrepair, Madison Square Park underwent a total renovation which was completed in June 2001. To recapture the park’s magnificence, the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation asked the City Parks Foundation to organize a revitalization campaign. Their "Campaign for the New Madison Square Park" was a precursor to the current Madison Square Park Conservancy,[12] a public-private partnership formed to watch over the park.

One amenity added to the park in July 2004 is the Shake Shack, a popular permanent stand that serves hamburgers, hot dogs, shakes and other similar food, as well as wine. Its distinctive building, which was designed by Sculpture in the Environment, an architectural and environmental design firm based in Lower Manhattan, sits near the south east entrance to the park.

The neighborhoods around Madison Square have changed frequently, and continue to do so. Commonly referred to as the Flatiron District, the area has, since the 1980s, changed from a primarily commercial district with many photographer's studios – which located there because of the relatively cheap rents – into a prime residential area. Madison Avenue continues to be mostly a business district, while Broadway just north of the square holds many small wholesale shops. The area west of the square remains mostly commercial, but with many residential structures being built.

Buildings

On the south end of Madison Square, southwest of the park, is the Flatiron Building, one of the oldest of the original New York skyscrapers, and just to east at 1 Madison Avenue is the Met Life Tower, built in 1909 and the tallest building in the world until 1913, when the Woolworth Building was completed. It is now occupied by Credit Suisse since MetLife moved their headquarters to the PanAm Building. The 700-foot (210 m) marble clock tower of this building dominates the park.

Nearby, on Madison Avenue between 26th and 27th Streets, on the site of the old Madison Square Garden, is the New York Life Building, built in 1928 and designed by Cass Gilbert, with a square tower topped by a striking gilded pyramid. Also of note is the statuary adorning the Appellate Division of the New York State Supreme Court on Madison Avenue at 25th Street.

As of June 2008, One Madison Park, a 51 story residential condominium tower is under construction at 22 East 23rd Street, at the foot of Madison Avenue, across from Madison Square Park. When completed, it will be almost as tall as or slightly taller than the Met Life Tower (604-617 feet, depending on the source, compared to 614 feet (187 m) for the Tower), and taller than the Flatiron Building.[13]

Gallery

|

|

|

|

|

|

See also

References

Bibliography

- Berman, Mirian, Madison Square: The Park and Its Celebrated Landmarks (2001) ISBN 1-58685-037-7

- Burrows, Edwin G & Wallace, Mike, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (1999) ISBN 0-19-511634-8

- Jackson, Kenneth T. (ed.), The Encyclopedia of New York (1995) ISBN 0-300-05536-6

- Moscow, Henry, The Street Book (1978) ISBN 0823212750

- Patterson, Jerry E. Fifth Avenue: The Best Address (1998)

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f Jackson, Kenneth T. (ed.), The Encyclopedia of New York City (1995) ISBN 0-300-05536-6

- ^ a b Patterson, Jerry E. Fifth Avenue: The Best Address (1998)

- ^ a b c d e f Burrows, Edwin G. & Wallace, Mike, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, (1999) ISBN 0-19-511634-8

- ^ History of the Internation Toy Center

- ^ a b White, Norval & Willensky, Elliot; AIA Guide to New York City (2000) ISBN 0-8129-31069-8

- ^ Moscow, Henry, The Street Book (1978) ISBN 0823212750

- ^ General Worth Square

- ^ NYC Parks Dept. Parks for a New Metropolis

- ^ Cather, Willa. My Mortal Enemy (1926) at Project Gutenberg of Australia

- ^ Gray, Christopher "Streetscapes", New York Times (4 September 1994)

- ^ Silver, Nathan, Lost New York (1968) ISBN 0618054758

- ^ Madison Square Park Conservancy

- ^ "47-story condo tower with 90 units planned for 23rd Street", Image of "The Saya"