Feng shui

Template:Contains Chinese text

| Feng shui | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

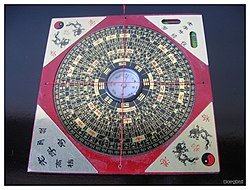

A Luopan, Feng shui compass. | |||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 風水 | ||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 风水 | ||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | wind-water | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese | Phong thủy | ||||||||||||||

| Thai name | |||||||||||||||

| Thai | [ฮวงจุ้ย (Huang Jui)] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | ||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 풍수 | ||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 風水 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 風水 | ||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | ふうすい | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Filipino name | |||||||||||||||

| Tagalog | pungsoy | ||||||||||||||

Feng shui (/ˌfʌŋˈʃweɪ/ fung-SHWAY,[1] formerly /ˈfʌŋʃuː.i/ FUNG-shoo-ee;[2] Chinese: 風水, pronounced [fə́ŋʂwèi]) is an ancient Chinese system of aesthetics believed to use the laws of both Heaven (astronomy) and Earth (geography) to help one improve life by receiving positive qi.[3] The original designation for the discipline is Kan Yu (simplified Chinese: 堪舆; traditional Chinese: 堪輿; pinyin: kānyú; literally: Tao of heaven and earth).[4]

The term feng shui literally translates as "wind-water" in English. This is a cultural shorthand taken from the following passage of the Zangshu (Book of Burial) by Guo Pu of the Jin Dynasty:[5]

Qi rides the wind and scatters, but is retained when encountering water.[5]

Historically, feng shui was widely used to orient buildings – often spiritually significant structures such as tombs, but also dwellings and other structures – in an auspicious manner. Depending on the particular style of feng shui being used, an auspicious site could be determined by reference to local features such as bodies of water, stars, or a compass. Feng shui was suppressed in China during the cultural revolution in the 1960s, but has since seen an increase in popularity, particularly in the United States.

History

Origins

Currently Yangshao and Hongshan cultures provide the earliest evidence for the practice of feng shui. Until the invention of the magnetic compass, feng shui apparently relied on astronomy to find correlations between humans and the universe.[6]

In 4000 BC, the doors of Banpo dwellings were aligned to the asterism Yingshi just after the winter solstice—this sited the homes for solar gain.[7] During the Zhou era, Yingshi was known as Ding and used to indicate the appropriate time to build a capital city, according to the Shijing. The late Yangshao site at Dadiwan (c. 3500-3000 BC) includes a palace-like building (F901) at the center. The building faces south and borders a large plaza. It is on a north-south axis with another building that apparently housed communal activities. The complex may have been used by regional communities.[8]

A grave at Puyang (c. 4000 BC) that contains mosaics—actually a Chinese star map of the Dragon and Tiger asterisms and Beidou (the Big Dipper, Ladle or Bushel) -- is oriented along a north-south axis.[9] The presence of both round and square shapes in the Puyang tomb, at Hongshan ceremonial centers and the late Longshan settlement at Lutaigang,[10] suggests that gaitian cosmography (heaven-round, earth-square) was present in Chinese society long before it appeared in the Zhou Bi Suan Jing.[11]

Cosmography that bears a striking resemblance to modern feng shui devices and formulas was found on a jade unearthed at Hanshan and dated around 3000 BC. The design is linked by archaeologist Li Xueqin to the liuren astrolabe, zhinan zhen, and Luopan.[12]

Beginning with palatial structures at Erlitou,[13] all capital cities of China followed rules of feng shui for their design and layout. These rules were codified during the Zhou era in the Kaogong ji (simplified Chinese: 考工记; traditional Chinese: 考工記; "Manual of Crafts"). Rules for builders were codified in the carpenter's manual Lu ban jing (simplified Chinese: 鲁班经; traditional Chinese: 魯班經; "Lu ban's manuscript"). Graves and tombs also followed rules of feng shui, from Puyang to Mawangdui and beyond. From the earliest records, it seems that the rules for the structures of the graves and dwellings were the same.

Early instruments and techniques

The history of feng shui covers 3,500+ years[14] before the invention of the magnetic compass. It originated in Chinese astronomy.[15] Some current techniques can be traced to Neolithic China,[16] while others were added later (most notably the Han dynasty, the Tang, the Song, and the Ming).[17]

The astronomical history of feng shui is evident in the development of instruments and techniques. According to the Zhouli the original feng shui instrument may have been a gnomon. Chinese used circumpolar stars to determine the north-south axis of settlements. This technique explains why Shang palaces at Xiaotun lie 10° east of due north. In some cases, as Paul Wheatley observed,[18] they bisected the angle between the directions of the rising and setting sun to find north. This technique provided the more precise alignments of the Shang walls at Yanshi and Zhengzhou. Rituals for using a feng shui instrument required a diviner to examine current sky phenomena to set the device and adjust their position in relation to the device.[19]

The oldest examples of instruments used for feng shui are liuren astrolabes, also known as shi. These consist of a lacquered, two-sided board with astronomical sightlines. The earliest examples of liuren astrolabes have been unearthed from tombs that date between 278 BC and 209 BC. Along with divination for Da Liu Ren[20] the boards were commonly used to chart the motion of Taiyi through the nine palaces.[21] The markings on a liuren/shi and the first magnetic compasses are virtually identical.[22]

The magnetic compass was invented for feng shui[23] and has been in use since its invention. Traditional feng shui instrumentation consists of the Luopan or the earlier south-pointing spoon (指南針 zhinan zhen)—though a conventional compass could suffice if one understood the differences. A feng shui ruler (a later invention) may also be employed.

Foundation theories

The goal of feng shui as practiced today is to situate the human built environment on spots with good qi. The "perfect spot" is a location and an axis in time.[24][25]

Qi (ch'i)

Qi (roughly pronounced as the sound 'chee' in English) is a movable positive or negative life force which plays an essential role in feng shui.[citation needed] In Chinese martial arts, it refers to 'energy', in the sense of 'life force' or élan vital.[citation needed] A traditional explanation of qi as it relates to feng shui would include the orientation of a structure, its age, and its interaction with the surrounding environment including the local microclimates, the slope of the land, vegetation, and soil quality.[citation needed]

The Book of Burial says that burial takes advantage of "vital qi." Wu Yuanyin[26] (Qing dynasty) said that vital qi was "congealed qi," which is the state of qi that engenders life. The goal of feng shui is to take advantage of vital qi by appropriate siting of graves and structures.[25]

One use for a Luopan is to detect the flow of qi.[27] Magnetic compasses reflect local geomagnetism which includes geomagnetically induced currents caused by space weather. [28] Professor Max Knoll suggested in a 1951 lecture that qi is a form of solar radiation.[29] As space weather changes over time,[30] and the quality of qi rises and falls over time,[25] feng shui with a compass might be considered a form of divination that assesses the quality of the local environment—including the effects of space weather.

Polarity

Polarity is expressed in feng shui as Yin and Yang Theory. Polarity expressed through yin and yang is similar to a magnetic dipole.[citation needed] That is, it is of two parts: one creating an exertion and one receiving the exertion. Yang acting and yin receiving could be considered an early understanding of chirality[citation needed]. The development of Yin Yang Theory and its corollary, Five Phase Theory (Five Element Theory), have also been linked with astronomical observations of sunspots.[31]

The five elements of feng shui (water, wood, fire, earth/soil, metal) are made of yin and yang in precise amounts (Greater wood has less yin than lesser wood, but not as much yin as water, and so forth).[citation needed] Earth is a buffer, or an equilibrium achieved when the polarities cancel each other.[citation needed] While the goal of Chinese medicine is to balance yin and yang in the body, the goal of feng shui has been described as aligning a city, site, building, or object with yin-yang force fields.[32]

Bagua (eight trigrams)

Two diagrams known as bagua (or pa kua) loom large in feng shui, and both predate their mentions in the Yijing (or I Ching). The Lo (River) Chart (Luoshu, or Later Heaven Sequence) was developed first.[33] The Luoshu and the River Chart (Hetu, or Early Heaven Sequence) are linked to astronomical events of the sixth millennium BC, and with the Turtle Calendar from the time of Yao.[34] The Turtle Calendar of Yao (found in the Yaodian section of the Shangshu or Book of Documents) dates to 2300 BC, plus or minus 250 years.[35]

In Yaodian, the cardinal directions are determined by the marker-stars of the mega-constellations known as the Four Celestial Animals.[35]

East: the Green Dragon (Spring equinox)—Niao (Bird), α Hydrae

South: the Red Phoenix (Summer solstice)—Huo (Fire), α Scorpionis

West: the White Tiger (Autumn equinox)—Xu (Emptiness, Void), α Aquarii, β Aquarii

North: the Dark Turtle (Winter solstice)—Mao (Hair), η Tauri (the Pleiades)

The diagrams are also linked with the sifang (four directions) method of divination used during the Shang dynasty.[36] The sifang is much older, however. It was used at Niuheliang, and figured large in Hongshan culture's astronomy. And it is this area of China that is linked to Huangdi, the Yellow Emperor, who allegedly invented the south-pointing spoon.[37]

School

A school or stream is a set of techniques or methods. The term should not be confused with an actual school—there are many masters who run schools.

Some claim[38] that authentic masters impart their genuine knowledge only to selected students, such as relatives.

Techniques

Archaeological discoveries from Neolithic China and the literature of ancient China together give us an idea of the origins of feng shui techniques. In premodern China, Yin feng shui (for tombs) had as much importance as Yang feng shui (for homes).[24] For both types one had to determine direction by observing the skies (what Wang Wei called the Ancestral Hall Method; later identified by Ding Juipu as Liqi pai, which westerners mistakenly label "compass school"),[25] and to determine the Yin and Yang of the land (what Wang Wei called the Kiangxi method and Ding Juipu called Xingshi pai, which westerners mistakenly label "form school").[25]

Feng shui is typically associated with the following techniques. This is not a complete list; it is merely a list of the most common techniques.[39][40]

Xingshi Pai ("Forms" Methods)

- Luan Dou Pai, 峦头派, Pinyin: luán tóu pài, (environmental analysis without using a compass)

- Xing Xiang Pai, 形象派 or 形像派, Pinyin: xíng xiàng pài, (Imaging forms)

- Xingfa Pai, 形法派, Pinyin: xíng fǎ pài

Liqi Pai ("Compass" Methods)

San Yuan Method, 三元派 (Pinyin: sān yuán pài)

- Dragon Gate Eight Formation, 龍門八法 (Pinyin: lóng mén bà fǎ)

- Xuan Kong, 玄空 (time and space methods)

- Xuan Kong Fei Xing 玄空飛星 (Flying Stars methods of time and directions)

- Xuan Kong Da Gua, 玄空大卦 ("Secret Decree" or 64 gua relationships)

San He Method, 三合派 (environmental analysis using a compass)

- Accessing Dragon Methods

- Ba Zhai, 八宅 (Eight Mansions)

- Water Methods, 河洛水法

- Local Embrace

Others

- Four Pillars of Destiny, 四柱命理 (a form of hemerology)

- Major & Minor Wandering Stars (Constellations)

- Five phases, 五行 (relationship of the five phases or wuxing)

Modern developments

One of the grievances mentioned when the anti-Western Boxer Rebellion erupted was that Westerners were violating the basic principles of feng shui in their construction of railroads and other conspicuous public structures throughout China. At the time, Westerners had little idea of, or interest in, such Chinese traditions. After Richard Nixon journeyed to the People's Republic of China in 1972, feng shui became somewhat of an industry in the USA.

It has since been reinvented by New Age entrepreneurs for Western consumption. Feng shui speaks to the profound role of magic, mystery, and order in American life.[41] The following list does not exhaust the modern varieties.

Black Sect—also called BTB Feng Shui—does not match documentary or archaeological evidence, or what is known of the history of Tantra in China.[42] It relies on "transcendental" methods, the concept of clutter as metaphor for life circumstances, and the use of affirmations or intentions to achieve results. The BTB Ba gua was developed by Lin Yun. Each of the eight sectors that were once aligned to compass points now represents a particular area of one's life.

In contemporary China, practitioners of the divination systems of Qi Men Dun Jia and Da Liu Ren adopt these modes of divination for highly detailed and analytic problem-solving in Feng Shui.[citation needed]

Feng shui today

Today, feng shui is practiced not only by the Chinese, but also by Westerners. However, with the passage of time and feng shui's popularization in the West, much of the knowledge behind it has been lost in translation, not paid proper attention to, frowned upon, or scorned.

Robert T. Carroll sums up what feng shui has become in some cases:

"... feng shui has become an aspect of interior decorating in the Western world and alleged masters of feng shui now hire themselves out for hefty sums to tell people such as Donald Trump which way his doors and other things should hang. Feng shui has also become another New Age "energy" scam with arrays of metaphysical products ... offered for sale to help you improve your health, maximize your potential, and guarantee fulfillment of some fortune cookie philosophy."[43]

Others have noted how, when feng shui is not applied properly, or rather, without common sense, it can even harm the environment, such as was the case of people planting "lucky bamboo" in ecosystems that could not handle them.[44] Still others are simply skeptical.

Nevertheless, even modern feng shui is not always looked at as a superstitious scam. Many people[who?] believe it is important and very helpful in living a prosperous and healthy life either avoiding or blocking negative energies that might otherwise have bad effects. Many of the higher-level forms of feng shui are not so easily practiced without either connections, or a certain amount of wealth because the hiring of an expert, the great altering of architecture or design, and the moving from place to place that is sometimes necessary requires a lot of money. Because of this, some people of the lower classes lose faith in feng shui, saying that it is only a game for the wealthy.[45] Others, however, practice less expensive forms of Feng Shui, including hanging special (but cheap) mirrors, forks, or woks in doorways to deflect negative energy.[46]

Even today feng shui is so important to some people[who?] that they use it for healing purposes, separate from western medical practice, in addition to using it to guide their businesses and create a peaceful atmosphere in their homes.[47] In 2005, even Disney acknowledged feng shui as an important part of Chinese culture by shifting the main gate to Hong Kong Disneyland by twelve degrees in their building plans, among many other actions suggested by the master planner of architecture and design at Walt Disney Imagineering, Wing Chao, in an effort to incorporate local culture into the theme park.[48]

The practice of Feng Shui is diverse and multi-faceted. There are many different schools and perspectives. The International Feng Shui Guild (IFSG) is a non-profit professional organization that presents the full diversity of Feng Shui.

At Singapore Polytechnic and other institutions like the New York College of Health Professions, many students (including engineers and interior designers) take courses on feng shui every year and go on to become feng shui (or geomancy) consultants.[49]

Feng Shui in the News

Some articles concerning feng shui that have made the news are listed below; in addition, feng shui has its own page in the New York Time's "Times Topics.":

- "The Feng Shui Kingdom”

- "And to My Loyal Feng Shui Advisor, I Leave $3 Billion"

- "Using Feng Shui in Offices and Stores"

- "I’ll Have a Big Mac, Serenity on the Side."

- "Home Is Where Harmony Is"

- "When Opposites Attract, Stick Together"

- "California Measure Would Align Building Rules With Feng Shui"

Current developments

A growing body of research exists on the traditional forms of feng shui used and taught in Asia.

Landscape ecologists find traditional feng shui an interesting study.[50] In many cases, the only remaining patches of old forest in Asia are "feng shui woods,"[51] often associated with cultural heritage, historical continuity, and the preservation of species.[52] Some researchers interpret the presence of these woods as indicators that the "healthy homes,"[53] sustainability[54] and environmental components of ancient feng shui should not be easily dismissed.[55][56]

Environmental scientists and landscape architects have researched traditional feng shui and its methodologies.[57][58][59]

Architects study feng shui as an ancient and uniquely Asian architectural tradition.[60][61][62][63]

Geographers have analyzed the techniques and methods to help locate historical sites in Victoria, Canada,[64] and archaeological sites in the American Southwest, concluding that ancient Native Americans considered astronomy and landscape features.[65]

See also

- Qi Men Dun Jia (Marvellous Gates and Hidden Jia Stems (Heavenly Stems) methods)

- Zi wei dou shu (Purple King, 24-star astrology)

- Da Liu Ren (hemerological calculations)

- Interior design

- Chinese spiritual world concepts

- Geomancy

- Geopathic stress

- Tiang Seri

- Vastu Shastra

- Feng shui society

- Four Symbols (Chinese constellation)

- Master Tham Fook Cheong

- Lillian Too

- Aaron Lee Koch

References

- ^ Random House, American Heritage, Merriam Webster

- ^ "feng-shui". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Tina Marie (2007–2009). "Feng Shui Diaries". Esoteric Feng Shui.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ "Baidu Baike". Huai Nan Zi.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Field, Stephen L. "The Zangshu, or Book of Burial".

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Sun, X. (2000) Crossing the Boundaries between Heaven and Man: Astronomy in Ancient China. In H. Selin (ed.), Astronomy Across Cultures: The History of Non-Western Astronomy. 423-454. Kluwer Academic.

- ^ David W. Pankenier. 'The Cosmo-Political Background of Heaven's Mandate.' Early China 20 (1995):121-176.

- ^ Li Liu. The Chinese Neolithic: Trajectories to Early States. Cambridge University Press (2004) 85-88.

- ^ Zhentao Xu, David W. Pankenier, and Yaotiao Jiang. East Asian Archaeoastronomy. 2000: 2

- ^ Li Liu. The Chinese Neolithic: Trajectories to Early States. Cambridge University Press (2004) 248–249.

- ^ Sarah M. Nelson, Rachel A. Matson, Rachel M. Roberts, Chris Rock and Robert E. Stencel. (2006) Archaeoastronomical Evidence for Wuism at the Hongshan Site of Niuheliang. Page 2.

- ^ Chen Jiujin and Zhang Jingguo. 'Hanshan chutu yupian tuxing shikao,' Wenwu 4, 1989:15

- ^ Li Liu. The Chinese Neolithic: Trajectories to Early States. Cambridge University Press (2004) 230-237.

- ^ Aihe Wang. Cosmology and Political Culture in Early China. 2000: 55

- ^ Feng Shi. Zhongguo zhaoqi xingxiangtu yanjiu. Zhiran kexueshi yanjiu, 2 (1990).

- ^ Aihe Wang. Cosmology and Political Culture in Early China. 2000: 54-55

- ^ Cheng Jian Jun and Adriana Fernandes-Gonçalves. Chinese Feng Shui Compass: Step by Step Guide. 1998: 21

- ^ The Pivot of the Four Quarters (1971: 46)

- ^ Mark Edward Lewis (2006). The Construction of Space in Early China. p. 275

- ^ Marc Kalinowski (1996). "The Use of the Twenty-eight Xiu as a Day-Count in Early China." Chinese Science 13 (1996): 55-81.

- ^ Yin Difei. "Xi-Han Ruyinhou mu chutu de zhanpan he tianwen yiqi." Kaogu 1978.5, 338-43; Yan Dunjie, "Guanyu Xi-Han chuqi de shipan he zhanpan." Kaogu 1978.5, 334-37.

- ^ Marc Kalinowski. 'The Xingde Texts from Mawangdui.' Early China. 23-24 (1998-99):125-202.

- ^ Wallace H. Campbell. Earth Magnetism: A Guided Tour Through Magnetic Fields. Academic Press, 2001.

- ^ a b Field, Stephen L. (1998). Qimancy: Chinese Divination by Qi.

- ^ a b c d e Bennett, Steven J. (1978) "Patterns of the Sky and Earth: A Chinese Science of Applied Cosmology." Journal of Chinese Science. 3:1-26

- ^ Tsang ching chien chu (Tse ku chai chung ch'ao, volume 76), p. 1a.

- ^ Field, Stephen L. (1998). Qimancy: The Art and Science of Fengshui.

- ^ Lui, A.T.Y., Y. Zheng, Y. Zhang, H. Rème, M.W. Dunlop, G. Gustafsson, S.B. Mende, C. Mouikis, and L.M. Kistler, Cluster observation of plasma flow reversal in the magnetotail during a substorm, Ann. Geophys., 24, 2005-2013, 2006

- ^ Max Knoll. "Transformations of Science in Our Age." In Joseph Campbell (ed.). Man and Time. Princeton UP, 1957, 264-306.

- ^ Wallace Hall Campbell. Earth Magnetism: A Guided Tour through Magnetic Fields. Harcourt Academic Press. 2001:55

- ^ Sarah Allan. The Shape of the Turtle: Myth, Art and Cosmos in Early China. 1991:31–32.

- ^ Frank J. Swetz (2002). The Legacy of the Luoshu. pp. 31, 58.

- ^ Frank J. Swetz (2002). Legacy of the Luoshu. p. 36-37

- ^ Deborah Lynn Porter. From Deluge to Discourse. 1996:35–38.

- ^ a b Sun and Kistemaker. The Chinese Sky During the Han. 1997:15–18.

- ^ Aihe Wang. Cosmology and Political Structure in Early China. 2000:107-128

- ^ Sarah M. Nelson, Rachel A. Matson, Rachel M. Roberts, Chris Rock, and Robert E. Stencel. Archaeoastronomical Evidence for Wuism at the Hongshan Site of Niuheliang. 2006

- ^ Jacky Cheung Ngam Fung (2007). "History of Feng Shui".

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Cheng Jian Jun and Adriana Fernandes-Gonçalves. Chinese Feng Shui Compass Step by Step Guide. 1998:46-47

- ^ MoonChin. Chinese Metaphysics: Essential FengShui Basics. ISBN 978-983-43773-1-1

- ^ H. L. Goodall, Jr. Writing the American Ineffable, or the Mystery and Practice of Feng Shui in Everyday Life. Qualitative Inquiry, 7:1, 3–20 (2001).

- ^ Chou Yi-liang. Tantrism in China. Harvard J. of Asiatic Studies, 8:3/4 (Mar., 1945), 241–332.

- ^ Robert T. Carroll, "feng shui - The Skeptic’s Dictionary"

- ^ Elizabeth Hilts, "Fabulous Feng Shui: It's Certainly Popular, But is it Eco-Friendly?"

- ^ Emmons, C. F. "Hong Kong's Feng Shui: Popular Magic in a Modern Urban Setting." Journal of Popular Culture, Volume 26, Issue 1, Summer 1992, p. 42

- ^ Emmons, C. F. "Hong Kong's Feng Shui: Popular Magic in a Modern Urban Setting." Journal of Popular Culture, Volume 26, Issue 1, Summer 1992, p. 46

- ^ Emmons, C. F. "Hong Kong's Feng Shui: Popular Magic in a Modern Urban Setting." Journal of Popular Culture, Volume 26, Issue 1, Summer 1992, p. 48

- ^ Laura M. Holson, "The Feng Shui Kingdom"

- ^ AsiaOne, "Feng Shui course gains popularity"

- ^ Bo-Chul Whang and Myung-Woo Lee. Landscape ecology planning principles in Korean Feng-Shui, Bi-bo woodlands and ponds. J. Landscape and Ecological Engineering. 2:2, November, 2006. 147-162.

- ^ Bixia Chen (February 2008). "A Comparative Study on the Feng Shui Village Landscape and Feng Shui Trees in East Asia." PhD dissertation, United Graduate School of Agricultural Sciences, Kagoshima University (Japan)

- ^ Marafa L. "Integrating natural and cultural heritage: the advantage of feng shui landscape resources." International Journal of Heritage Studies, Volume 9, Number 4, December 2003 , pp. 307-323(17)

- ^ Qigao Chen, Ya Feng, Gonglu Wang. Healthy Buildings Have Existed in China Since Ancient Times. Indoor and Built Environment, 6:3, 179-187 (1997)

- ^ Stephen Siu-Yiu Lau, Renato Garcia, Ying-Qing Ou, Man-Mo Kwok, Ying Zhang, Shao Jie Shen, Hitomi Namba. Sustainable design in its simplest form: Lessons from the living villages of Fujian rammed earth houses. Structural Survey. 2005, 23:5, 371-385

- ^ Xue Ying Zhuang, Richard T. Corlett. Forest and Forest Succession in Hong Kong, China. J. of Tropical Ecology, 13:6 (Nov., 1997), 857

- ^ Marafa, L. M. Integrating Natural and Cultural Heritage: the advantage of feng shui landscape resources. Intl. J. Heritage Studies. 2003, 9: Part 4, 307-324

- ^ Chen, B. X. and Nakama, Y. A summary of research history on Chinese Feng-shui and application of feng shui principles to environmental issues. Kyusyu J. For. Res. 57. 297-301 (2004).

- ^ Xu, Jun. 2003. A framework for site analysis with emphasis on feng shui and contemporary environmental design principles. Blacksburg, Va: University Libraries, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

- ^ Lu, Hui-Chen. 2002. A Comparative analysis between western-based environmental design and feng-shui for housing sites. Thesis (M.S.). California Polytechnic State University, 2002.

- ^ Park, C.-P. Furukawa, N. Yamada, M. A Study on the Spatial Composition of Folk Houses and Village in Taiwan for the Geomancy (Feng-Shui). J. Arch. Institute of Korea. 1996, 12:9, 129-140.

- ^ Xu, P. Feng-Shui Models Structured Traditional Beijing Courtyard Houses. J. Architectural and Planning Research. 1998, 15:4, 271-282.

- ^ Hwangbo, A. B. An Alternative Tradition in Architecture: Conceptions in Feng Shui and Its Continuous Tradition. J. Architectural and Planning Research. 2002, 19:2, pp 110-130.

- ^ Su-Ju Lu; Peter Blundell Jones. House design by surname in Feng Shui. J. of Architecture. 5:4 December 2000, 355-367.

- ^ Chuen-Yan David Lai. A Feng Shui Model as a Location Index. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 64 (4), 506-513.

- ^ Xu, P. Feng-shui as Clue: Identifying Ancient Indian Landscape Setting Patterns in the American Southwest. Landscape Journal. 1997, 16:2, 174-190.

Further reading

- Ole Bruun. "Fengshui and the Chinese Perception of Nature," in Asian Perceptions of Nature: A Critical Approach, eds. Ole Bruun and Arne Kalland (Surrey: Curzon, 1995) 173-88

- Ole Bruun. Fengshui in China: Geomantic Divination between State Orthodoxy and Popular Religion. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2003.

- Ole Bruun. An Introduction to Feng Shui. Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Yoon, Hong-key. Culture of Fengshui in Korea: An Exploration of East Asian Geomancy, Lexington Books, 2006.

- "Magnetic alignment in grazing and resting cattle and deer," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences published ahead of print August 25, 2008, doi:10.1073/pnas.0803650105

- Xie, Shan Shan' Chinese Geographic Feng Shui Theories and Practices National Multi-Attribute Institute Publishing, Oct. 2008, ISBN 978-159261-0048