Terry Pratchett

Sir Terry Pratchett | |

|---|---|

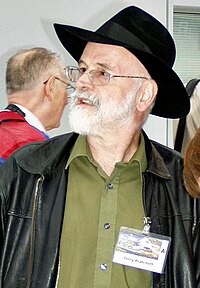

Pratchett speaking about dementia in 2009 | |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Nationality | British |

| Genre | Comic fantasy |

| Notable works | Discworld Good Omens |

| Signature | |

| File:Terrys-signature.svg | |

| Website | |

| http://www.terrypratchett.co.uk/ | |

Sir Terence David John Pratchett, OBE (born 28 April 1948),[3] more commonly known as Terry Pratchett, is an English[4] novelist, known for his frequently comical work in the fantasy genre. He is best-known for his popular and long-running Discworld series of comic fantasy novels. Pratchett's first novel, The Carpet People, was published in 1971, and since his first Discworld novel (The Colour of Magic) was published in 1983, he has written two books a year on average.

Pratchett was the UK's best-selling author of the 1990s,[5][6] and as of December 2007 had sold more than 55 million books worldwide,[7] with translations made into 36 languages.[8]

He is currently the second most-read writer in the UK, and seventh most-read non-US author in the US.[9] In 2001 he won the Carnegie Medal for his young adult novel The Amazing Maurice and his Educated Rodents.[10]

Pratchett was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) "for services to literature" in 1998.[8] He was in addition knighted in the 2009 New Year Honours.[11][12] In December 2007, Pratchett publicly announced that he was suffering from early-onset Alzheimer's disease, subsequently making a substantial public donation to the Alzheimer's Research Trust,[13] and filming a programme chronicling his experiences with the disease for the BBC.[14]

Background

Early life

Pratchett was born in 1948 in Beaconsfield in Buckinghamshire, England, the only child of David and Eileen Pratchett, of Hay-on-Wye. His family moved to Bridgwater, Somerset briefly in 1957, following which he passed his eleven plus exam in 1959, earning him a place in John Hampden Grammar School.[15] Pratchett described himself as a "non-descript student", and in his Who's Who entry, credits his education to the Beaconsfield Public Library.[16]

His early interests included astronomy;[17] he collected Brooke Bond tea cards about space, owned a telescope[18] and desired to be an astronomer, but lacked the necessary mathematical skills.[17] However, this led to an interest in reading British and American science fiction.[18] In turn, this led to attending science fiction conventions from about 1963/4, which stopped when he got his first job a few years later.[18] His early reading included the works of H. G. Wells and Arthur Conan Doyle and "every book you really ought to read" which he now regards as "getting an education".[19]

At age 13, Pratchett published his first short story "The Hades Business" in the school magazine. It was published commercially when he was 15.[20]

Pratchett earned 5 O-levels and started A-level courses in Art, English and History. Pratchett's first career choice was journalism and he left school at 17 in 1965 to start working for the Bucks Free Press where he wrote, amongst other things, several stories for the Children's Circle section under the name Uncle Jim. One of these episodic stories contains named characters from The Carpet People. These stories are currently part of a project by the Bucks Free Press to make them available online. [21] While on day release he finished his A-Level in English and took a proficiency course for journalists.[22]

Early career

Pratchett had his first breakthrough in 1968, when working as a journalist. He came to interview Peter Bander van Duren, co-director of a small publishing company. During the meeting, Pratchett mentioned he had written a manuscript, The Carpet People.[23] Bander van Duren and his business partner, Colin Smythe (of Colin Smythe Ltd Publishers) published the book in 1971, with illustrations by Pratchett himself.[22] The book received strong, if few reviews.[22] The book was followed by the science fiction novels The Dark Side of the Sun and Strata, published in 1976 and 1981, respectively.[22]

After various positions in journalism, in 1980 Pratchett became Press Officer for the Central Electricity Generating Board in an area which covered three nuclear power stations. He later joked that he had demonstrated "impeccable timing" by making this career change so soon after the Three Mile Island nuclear accident in Pennsylvania, USA, and said he would "write a book about his experiences, if he thought anyone would believe it".[24]

The first Discworld novel The Colour of Magic was published in 1983 by Colin Smythe in hardback. The publishing rights for paperback were soon taken by Corgi, an imprint of Transworld, the current publisher. Pratchett received further popularity after the BBC's Woman's Hour broadcast The Colour of Magic as a serial in six parts, after it was published by Corgi in 1985 and later Equal Rites. Subsequently, rights for hardback were taken by the publishing house Victor Gollancz, which remained Pratchett's publisher until 1997, and Smythe became Pratchett's agent. Pratchett was the first fantasy author published by Gollancz.[22]

Pratchett gave up working for the CEGB in 1987 after finishing the fourth Discworld novel, Mort, to focus fully on and make his living through writing. His sales increased quickly and many of his books occupied top places on the best-seller list. According to The Times, Pratchett was the top selling and highest earning UK author in 1996.[22] Some of his books have been published by Doubleday, another Transworld imprint. In the US, Pratchett is published by HarperCollins.

According to the Bookseller's Pocket Yearbook from 2005, in 2003 Pratchett's UK sales amounted to 3.4% of the fiction market by hardback sales and 3.8% by value, putting him in 2nd place behind J. K. Rowling (6% and 5.6% respectively), while in the paperback sales list Pratchett came 5th with 1.2% by sales and 1.3% by value (behind James Patterson (1.9% and 1.7%), Alexander McCall Smith, John Grisham and J. R. R. Tolkien).[25] His sales in the UK alone are more than 2.5 million copies a year.[9]

Current life

Terry Pratchett married his wife Lyn in 1968,[22] and they moved to Rowberrow, Somerset in 1970. Their daughter Rhianna Pratchett, who is also a writer, was born there in 1976. In 1993 the family moved to a village north west of Salisbury, Wiltshire, where they currently live. He lists his recreations as "writing, walking, computers, life". [26] He describes himself as a humanist and is a Distinguished Supporter of the British Humanist Association.[27] and an Honorary Associate of the National Secular Society[28].

Pratchett is well known for his penchant for wearing large, black fedora hats,[29] as seen on the inside back covers of most of his books. His style has been described as "more that of urban cowboy than city gent."[30]

Concern for the future of civilisation has prompted him to install five kilowatts of photovoltaic cells (for solar energy) at his house.[31] In addition, his interest in astronomy since childhood has led him to build an observatory in his garden.[17][18]

On 31 December 2008 it was announced that Pratchett was to be knighted (as a Knight Bachelor) in the Queen's 2009 New Year Honours.[11][32] He formally received the accolade at Buckingham Palace on 18 February 2009.[33] Afterwards he said, "You can't ask a fantasy writer not to want a knighthood. You know, for two pins I'd get myself a horse and a sword."[34]

Alzheimer's disease

In August 2007, Pratchett was misdiagnosed as having had a minor stroke in 2004 or 2005, which was believed to have damaged the right side of his brain. While his motor skills had been affected, the observed damage had not impaired his ability to write.[30] On 11 December 2007, Pratchett posted online that he had been newly diagnosed with a very rare form of early-onset Alzheimer's disease, which he said "lay behind this year's phantom 'stroke'." He has a rare form of the disease called posterior cortical atrophy, in which areas at the back of the brain begin to shrink and shrivel.[13] Pratchett appealed to people to "keep things cheerful", and proclaimed that "we are taking it fairly philosophically down here and possibly with a mild optimism."[35] Leading the way, Pratchett stated that he feels he has time for "at least a few more books yet", and added that while he understands the impulse to ask 'is there anything I can do?', in this particular case he will only entertain such offers from "very high-end experts in brain chemistry."[35] Discussing his diagnosis at the Bath Literature Festival, Pratchett revealed that he now found it too difficult to write dedications when signing books.[36]

In March 2008, Pratchett announced he was donating US$1,000,000 (about £494,000 at the time) to the Alzheimer's Research Trust, saying that he had spoken to at least three brain tumour (cancer) survivors yet he had spoken to no survivors of Alzheimer's disease, and that he was shocked "to find out that funding for Alzheimer's research is just 3% of that to find cancer cures."[13][37][38] Of his donation Pratchett said: "I am, along with many others, scrabbling to stay ahead long enough to be there when the Cure comes along.”[39] Pratchett's donation inspired an internet campaign where fans hope to 'Match it for Pratchett', by raising another $1,000,000.[40]

In April 2008, the BBC began working with Pratchett to make a two-part documentary series based on his illness.[41] The first part of Terry Pratchett: Living With Alzheimer's was broadcast on BBC Two on 4 February 2009, drawing 2.6m viewers and a 10.4% audience share.[42] The second, broadcast on 11 February 2009, drew 1.72m viewers and a 6.8% audience share.[43] He also made an appearance on The One Show on 15 May 2008, talking about his condition. He was the subject and interviewee of the 20 May 2008 edition of On the Ropes (Radio 4), discussing Alzheimer's and how it had affected his life.

On 8 June 2008, news reports indicated that Pratchett had an experience, which he described as: "It is just possible that once you have got past all the gods that we have created with big beards and many human traits, just beyond all that, on the other side of physics, there just may be the ordered structure from which everything flows" and "I don’t actually believe in anyone who could have put that in my head".[44][45] He went into further detail on Front Row, in which he was asked if this was a shift in his beliefs: "A shift in me in the sense I heard my father talk to me when I was in the garden one day. But I'm absolutely certain that what I heard was my memories of my father. An engram, or something in my head."..."This is not about God, but somewhere around there is where gods come from."[46]

On 26 November 2008, Pratchett met the Prime Minister Gordon Brown and asked for an increase in dementia research funding.[47]

Since August 2008, Pratchett has been testing out a prototype anti-dementia helmet developed by doctor Gordon Dougal, which is to be worn for six minutes daily. After three months there were small improvements in his condition.[48] Many experts however are sceptical.[49]

In an article published mid 2009, Pratchett stated that he wishes to commit 'assisted suicide' (although he dislikes that term) before his disease progresses to a critical point.[50] Pratchett was selected to give the 2010 BBC Richard Dimbleby Lecture,[51] entitled Shaking Hands With Death, which was broadcast on 1 February 2010.[52] Pratchett introduced his lecture on the topic of assisted death, but the main text was read by his friend Tony Robinson because of difficulties Pratchett has with reading – a result of his condition.[53][54][55]

Interests

Computers and the Internet

Pratchett started to use computers for writing as soon as they were available to him. His first computer was a Sinclair ZX81, the first computer he properly used for writing was an Amstrad CPC 464, later replaced by a PC. Pratchett was one of the first authors to routinely use the Internet to communicate with fans, and has been a contributor to the Usenet newsgroup alt.fan.pratchett since 1992.[56] However, he does not consider the Internet a hobby, just another "thing to use".[24] He now has many computers in his house.[24] When he travels, he always takes a portable computer with him to write.[24] His experiments with computer upgrades are reflected in Hex.[57]

Pratchett is also an avid computer game player, and he has collaborated in the creation of a number of game adaptations of his books. He favours games that are "intelligent and have some depth", and has used Half-Life 2 and fan missions from Thief as examples.[58]

Natural history

Pratchett has a fascination with natural history that he has referred to many times. Pratchett owns a greenhouse full of carnivorous plants[59]

Orangutans

Pratchett is a trustee for the Orangutan Foundation UK[60] but is pessimistic about the animal's future.[31] Following Pratchett's lead, fan events such as the Discworld Conventions have adopted the Orangutan Foundation as their nominated charity, which has been acknowledged by the foundation.[61] One of Pratchett's most popular fictional characters, the Librarian of the Unseen University's Library, is an orangutan.

Amateur astronomy

Pratchett has an observatory in his back garden and is a keen astronomer. He has been on the BBC programme The Sky at Night.[62]

Writing career

Awards

Pratchett received a knighthood for "services to literature" in the 2009 UK New Year Honours list.[11][63] He was previously appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire, also for "services to literature", in 1998. Following this, Pratchett commented in the Ansible SF/fan newsletter, "I suspect the 'services to literature' consisted of refraining from trying to write any" (suggesting the title was more a recognition of success, than an acknowledgement of the fantasy genre). But then added, "Still, I cannot help feeling mightily chuffed about it."[64]

Pratchett was the British Book Awards' 'Fantasy and Science Fiction Author of the Year' for 1994.[65]

Pratchett won the British Science Fiction Award in 1989 for his novel, Pyramids,[66] and a Locus Award for Best Fantasy Novel in 2008 for Making Money.[67]

Pratchett has been awarded eight honorary Doctorates; University of Warwick in 1999,[68] the University of Portsmouth in 2001,[69] the University of Bath in 2003,[70] the University of Bristol in 2004,[71] Buckinghamshire New University in 2008,[72] Trinity College Dublin in 2008,[73] Bradford University in 2009,[74] and the University of Winchester in 2009.[75]

The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents won the 2001 Carnegie Medal for best children's novel (awarded in 2002).[76] Night Watch won the 2003 Prometheus Award for best libertarian novel.[77]

In 2003 Pratchett joined Charles Dickens as the two authors with five books in the BBC's Big Read 'Top 100' (four of which were Discworld novels). Pratchett was also the author with the most novels in the 'Top 200' (fifteen).[78] The three Discworld novels that centred on the character Tiffany Aching 'trainee witch' have each received the Locus Award for Best Young Adult Book (in 2004, 2005 and 2007).[79]

Pratchett was the recipient of NESFA's Skylark Award in 2009.[80]

Fandom

Pratchett's Discworld novels have led to dedicated conventions, the first in Manchester in 1996,[81] then worldwide,[82] often with the author as guest of honour.[83] Publication of a new novel may also be accompanied by an international book signing tour;[84] queues have been known to stretch outside the bookshop and the author has continued to sign books well after the intended finishing time.[81] His fans are not restricted by age or gender, and he receives a large amount of fan mail from them.[81] Pratchett enjoys meeting fans and hearing what they think about his books; he says that since he is well paid for his novels, his fans "are everything to me."[85]

Writing

Pratchett has said that to write, you must read extensively, both inside and outside your chosen genre[86] and to the point of "overflow".[24] He advises that writing is hard work, and that writers must "make grammar, punctuation and spelling a part of your life."[24] However, Pratchett enjoys writing, regarding its monetary rewards as "an unavoidable consequence", rather than the reason for writing.[87]

The fantasy genre

Although in the past he has written in the sci-fi and horror genres, Pratchett now focuses almost entirely on fantasy, explaining "it is easier to bend the universe around the story".[88] In the acceptance speech for his Carnegie Medal he said: 'Fantasy isn’t just about wizards and silly wands. It's about seeing the world from new directions', pointing to J. K. Rowling's Harry Potter novels and J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings. In the same speech, he also acknowledged benefits of these works for the genre.[89]

He "believes he owes a debt to the science fiction/fantasy genre which he grew up out of" and dislikes the term "magical realism" which is "like a polite way of saying you write fantasy and is more acceptable to certain people ... who, on the whole, do not care that much."[90] He is annoyed that fantasy is "unregarded as a literary form" because it "is the oldest form of fiction"[85] and he is "infuriated" when novels containing science fiction or fantasy ideas are not regarded as part of those genres.[86]

On 31 July 2005, Pratchett criticised media coverage of Harry Potter author J. K. Rowling, commenting that certain members of the media seemed to think that "the continued elevation of J. K. Rowling can only be achieved at the expense of other writers".[91] Pratchett has denied claims that this was a swipe at Rowling, and said that he was not making claims of plagiarism, but was pointing out the "shared heritage" of the fantasy genre.[92] Pratchett has also posted on the Harry Potter newsgroup about a media-covered exchange of views with her.[93]

Style and major themes

Pratchett is known for a distinctive writing style that includes a number of characteristic hallmarks. One example is his use of footnotes,[94] which usually involve a comic departure from the narrative or a commentary on the narrative.[95]

Pratchett has a tendency to avoid using chapters, arguing in a Book Sense interview that "life does not happen in regular chapters, nor do movies, and Homer did not write in chapters", adding "I'm blessed if I know what function they serve in books for adults."[96] However, there have been exceptions; Going Postal and Making Money and several of his books for younger readers are divided into chapters.[97]

Characters, place names, and titles in Pratchett's books often contain puns, allusions and culture references.[98][99] Some characters are parodies of well-known characters: for example, Pratchett's character Cohen the Barbarian is a parody of Conan the Barbarian and Genghis Khan, and his character Leonard of Quirm is a parody of Leonardo da Vinci.

Another hallmark of his writing is the use of capitalised dialogue without quotation marks, used to indicate the character of Death communicating telepathically into a character's mind. Other characters or types of characters have similarly distinctive ways of speaking, such as the auditors of reality never having quotation marks, Ankh-Morpork grocers never using punctuation correctly, or golems capitalising each word in everything they say. Pratchett also made up a new colour, Octarine, a 'fluorescent greenish-yellow-purple', which is the eighth colour in the Discworld spectrum - the colour of magic.[100] Indeed, the number eight itself is regarded in the Discworld as being a magical number; for example, the eighth son of an eighth son will be a wizard, and his eighth son will be a "sourcerer" (which is why wizards aren't allowed to have children).[101]

Discworld novels often include a modern innovation and its introduction to the world's medieval setting, such as a public police force (Guards! Guards!), gun (Men at Arms), submarine (Jingo),cinema (Moving Pictures), investigative journalism (The Truth), the postal service (Going Postal), or modern banking (Making Money). The resulting social upheaval serves as the setting for the main story and often inspires the title.[citation needed]

Influences

Pratchett makes no secret of outside influences on his work: they are a major source of his humour. He imports numerous characters from classic literature, popular culture and ancient history,[102] always adding an unexpected twist. Pratchett is a crime novel fan, which is reflected in frequent appearances of the Ankh-Morpork City Watch in the Discworld series.[88] Pratchett was an only child, and his characters are often without siblings. Pratchett explains "in fiction, only-children are the interesting ones."[103] An example is the character Susan Sto Helit.

Pratchett's earliest inspirations were The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame, and the works of Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke.[5] His literary influences have been P.G. Wodehouse, Tom Sharpe, Jerome K. Jerome, Larry Niven, Roy Lewis,[104] G. K. Chesterton, and Mark Twain.[105]

Publishing history

While Pratchett's UK publishing history has remained quite stable, his relationships with international publishers have been turbulent (especially in America). He changed German publishers after an advertisement for Maggi soup appeared in the middle of the German-language version of Pyramids.[106][107]

Bibliography

The Discworld series

Pratchett's Discworld series is a humorous and often satirical sequence of stories set in the colourful fantasy world of Discworld. The series contains various 'story arcs' (or 'sub-series'), and a number of free-standing stories. All are set in an abundance of locations in the same detailed and unified world, such as the Unseen University and 'The Drum/Broken Drum/Mended Drum' public house in the twin city Ankh-Morpork, or places in the various continents, regions and countries on the Disc. Characters and locations reappear throughout the series, variously taking major and minor roles.

The Discworld itself is described as a large disc resting on the backs of four giant elephants, all supported by the giant turtle Great A'Tuin as it swims its way through space. The books are essentially in chronological order,[97] and advancements can be seen in the development of the Discworld civilisations, such as the creation of paper money in Ankh-Morpork.[96]

The subject of many of the novels in Pratchett's Discworld series is a parody of a real-world subject such as film making, newspaper publishing, rock and roll music, religion, philosophy, Ancient Greece, Egyptian history, the Gulf War, Australia, university politics, trade unions, and the financial world. Pratchett has also included further parody as a feature within the stories, including such subjects as Ingmar Bergman films, numerous fiction, science fiction and fantasy characters, and various bureaucratic and ruling systems.

Other Discworld books

Pratchett has written or collaborated on a number of Discworld books that are not novels in themselves but serve to accompany the series.

The Discworld Companion, written with Stephen Briggs, is an encyclopedic guide to Discworld. The third (and latest) edition was renamed The New Discworld Companion, and was published in 2003. Briggs also collaborated with Pratchett on a series of fictional Discworld "mapps". The first, The Discworld Mapp (1995), illustrated by Stephen Player, comprises a large, comprehensive map of the Discworld itself with a small booklet that contains short biographies of the Disc's prominent explorers and their discoveries. Three further "mapps", have been released, focusing on particular regions of the Disc: Ankh-Morpork, Lancre, and Death's Domain. Briggs and Pratchett have also released several Discworld diaries and, with Tina Hannan, Nanny Ogg's Cookbook (1999). The design of this cookbook, illustrated by Paul Kidby, was based on the traditional Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management, but with humorous recipes.

Collections of Discworld-related art have also been released in book form. The Pratchett Portfolio (1996) and The Art of Discworld (2004) are collections of paintings of major Discworld characters by Paul Kidby, with details added by Pratchett on the character's origins.

In 2005, Pratchett's first book for very young children was Where's My Cow? Illustrated by Melvyn Grant, this is a realisation of the short story Sam Vimes reads to his child in Thud!.

Pratchett resisted mapping the Discworld for quite some time, noting that a firmly-designed map restricts narrative possibility (i.e., with a map, fans will complain if he places a building on the wrong street, but without one, he can adjust the geography to fit the story).

Science of Discworld

Pratchett has written three Science of Discworld books in collaboration with Professor of mathematics Ian Stewart and reproductive biologist Jack Cohen, both of the University of Warwick: The Science of Discworld (1999), The Science of Discworld II: The Globe (2002), and The Science of Discworld III: Darwin's Watch (2005).

All three books have chapters that alternate between fiction and non-fiction: the fictional chapters are set within the Discworld, where its characters observe, and experiment on, a universe with the same physics as ours. The non-fiction chapters (written by Stewart and Cohen) explain the science behind the fictional events.

In 1999, Pratchett appointed both Cohen and Stewart as "Honorary Wizards of the Unseen University" at the same ceremony at which the University of Warwick awarded him an honorary degree.[68]

Folklore of Discworld

Pratchett has collaborated with the folklorist Dr Jacqueline Simpson on The Folklore of Discworld (2008), a study of the relationship between many of the persons, places and events described in the Discworld books and their counterparts in myths, legends, fairy tales and folk customs on Earth.

Other novels

Pratchett's first two adult novels, The Dark Side of the Sun (1976) and Strata (1981), were both science-fiction, the latter taking place partly on a disc-shaped world. Subsequent to these, Pratchett has mostly concentrated on his Discworld series and novels for children, with two exceptions: Good Omens (1990), a collaboration with Neil Gaiman (which was nominated for both Locus and World Fantasy Awards in 1991[108]), a humorous story about the Apocalypse set on Earth and Nation (2008), a book for young adults.

After writing Good Omens, Pratchett began to work with Larry Niven on a book that would become Rainbow Mars; Niven eventually completed the book on his own, but states in the afterword that a number of Pratchett's ideas remained in the finished version.

Children's novels

Pratchett's first children's novel was also his first published novel: The Carpet People in 1971, which Pratchett substantially rewrote and re-released in 1992. The next, Truckers (1988), was the first in The Bromeliad trilogy of novels for young readers, about small gnome-like creatures called "Nomes", and the trilogy continued in Diggers (1990) and Wings (1990). Subsequently, Pratchett wrote the "Johnny Maxwell" trilogy, about the adventures of a boy called Johnny Maxwell and his friends, comprising Only You Can Save Mankind (1992), Johnny and the Dead (1993) and Johnny and the Bomb (1996). Nation (2008) marks his return to the non-Discworld children's novel.

Collaborations and contributions

- The Unadulterated Cat is a humorous book of cat anecdotes written by Pratchett and illustrated by Gray Jolliffe.

- After the King: Stories In Honour of J.R.R. Tolkien edited by Martin H. Greenberg (1992) contains "Troll Bridge", a short story featuring Cohen the Barbarian. This story was also published in the compilations Knights of Madness (1998, edited by Peter Haining) and The Mammoth Book of Comic Fantasy (2001, edited by Mike Ashley).

- The Wizards of Odd, a short-story compilation edited by Peter Haining (1996), includes a Discworld short story called "Theatre of Cruelty".

- The Flying Sorcerers, another short-story compilation edited by Peter Haining (1997), starts off with a Pratchett story called "Turntables of the Night", featuring Death (albeit not set on Discworld, but in our "reality").

- Legends, edited by Robert Silverberg (1998), contains a Discworld short story called "The Sea and Little Fishes".

- Digital Dreams, edited by David V Barrett (1990), contains the science fiction short story "# ifdefDEBUG + “world/enough” + “time”.

- Meditations on Middle-Earth (2002)

- The Leaky Establishment, written by David Langford (1984), has a foreword by Pratchett in later reissues (from 2001).

- Once More* With Footnotes, edited by Priscilla Olson and Sheila M. Perry (2004), is "an assortment of short stories, articles, introductions, and ephemera" by Pratchett which "have appeared in books, magazines, newspapers, anthologies, and program books, many of which are now hard to find."[109]

- Now We Are Sick, written by Neil Gaiman and Stephen Jones (1994), includes the poem called "The Secret Book of the Dead" by Pratchett.

- The Writers' and Artists' Yearbook 2007 includes an article by Pratchett about the process of writing fantasy.

- Good Omens, written with Neil Gaiman (1990)

- The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Fantasy, edited by David Pringle (1998), has a foreword by Pratchett.[110]

Adaptations

Radio

Pratchett has had a number of radio adaptations on BBC Radio 4: The Colour of Magic, Equal Rites (on Woman's Hour), Only You Can Save Mankind, Guards! Guards!, Wyrd Sisters, Mort, and Small Gods have all been dramatised as serials, as was Night Watch in early 2008, and The Amazing Maurice and his Educated Rodents as a 90-minute play.[111]

Additionally, Guards! Guards! was also adapted as a one-hour audio drama by the Atlanta Radio Theatre Company and performed live at Dragon*Con in 2001.

Theatre

Johnny and the Dead and 14 Discworld novels have been adapted as plays by Stephen Briggs and published in book form.[112] In addition, Lords & Ladies has been adapted for the stage by Irana Brown, and Pyramids was adapted for the stage by Suzi Holyoake in 1999 and had a week-long theatre run in the UK.[113] In 2002, an adaptation of Truckers was produced as a co-production between Harrogate Theatre, the Belgrade Theatre Coventry and Theatre Royal, Bury St. Edmunds. It was adapted by Bob Eaton, and directed by Rob Swain. The play toured to many venues in the UK between 15 March and 29 June 2002.[114]

In 2004, a musical adaptation of Only You Can Save Mankind was premiered at the Edinburgh Festival, with music by Leighton James House and book and lyrics by Shaun McKenna.[115]

In January 2009 the National Theatre in London announced that their annual Winter family production in 2009 would be a theatrical adaptation of Pratchett's novel Nation. The novel was adapted by playwright Mark Ravenhill and directed by Melly Still, director of the National Theatre's highly successful 2005 Winter family show Coram Boy.[116][117] The production premiered at the Olivier Theatre on 24 November, and ran until 28 March 2010. It was broadcast to cinemas around the world on 30 January 2010[118].

Television

Truckers was adapted as a stop motion animation series for Thames Television by Cosgrove Hall Films in 1992. Johnny and the Dead was made into a TV serial for Children's ITV on ITV, in 1995. Wyrd Sisters and Soul Music were adapted as animated cartoon series by Cosgrove Hall for Channel 4 in 1996; illustrated screenplays of these were published in 1998 and 1997 respectively. In January 2006, BBC One aired a three-part adaptation of Johnny and the Bomb.

A two-part, feature-length version of Hogfather starring David Jason and the voice of Ian Richardson was first aired on Sky One in the United Kingdom in December 2006, and on ION Television in the USA in 2007. Pratchett was opposed to live action films about Discworld before because of his negative experience with Hollywood film makers.[119] He changed his opinion when he saw that the director Vadim Jean and producer Rod Brown were very enthusiastic and cooperative.[120] A two-part, feature-length adaptation of The Colour of Magic and its sequel The Light Fantastic aired during Easter 2008 on Sky One.[121] A third adaptation, Going Postal was aired at the end of May 2010.

Feature films

Pratchett has held back from Discworld feature films;[122] though the rights to a number of his books have been sold, no films have yet been made. The Wee Free Men is set to be directed by Sam Raimi but has not started filming.[123] Director Terry Gilliam has announced in an interview with Empire magazine that he plans to adapt Good Omens[124] but as of 2007 this still needed funding.[125] In 2001, DreamWorks also commissioned an adaptation of Truckers by Andrew Adamson and Joe Stillman[126] but Pratchett believes that it will not be made until after "Shrek 17".[127] However, in 2008 Danny Boyle revealed that he hoped to direct a Truckers adaptation by Frank Cottrell Boyce.[128]

Comic books and graphic novels

Four graphic novels of Pratchett's work have been released. The first two, originally published in the US, were adaptations of The Colour of Magic and The Light Fantastic and illustrated by Steven Ross (with Joe Bennett on the latter). The second two, published in the UK, were adaptations of Mort (subtitled A Discworld Big Comic) and Guards! Guards!, both illustrated by Graham Higgins and adapted by Stephen Briggs. The graphic novels of The Colour of Magic and The Light Fantastic were republished by Doubleday on the 2 June 2008.

Role-playing games

GURPS Discworld (Steve Jackson Games, 1998) and GURPS Discworld Also (Steve Jackson Games, 2001) are role-playing source books which were written by Terry Pratchett and Phil Masters, which also offer insights into the workings of the Discworld. The first of these two books was re-released in September 2002 under the name of The Discworld Roleplaying Game, with art by Paul Kidby.

PC and console games

The Discworld universe has also been used as a basis for a number of Discworld video games on a range of formats, such as the Sega Saturn, the Sony Playstation, the Philips CD-i and the 3DO, as well as DOS and Windows-based PCs. The following are the more notable games:

- The Colour of Magic, the first game based on the series, and so far the only one directly adapted from a Discworld novel. It was released in 1986 for the Sinclair ZX Spectrum and Commodore 64.

- Discworld, an animated "point-and-click" adventure game made by Teeny Weeny Games and Perfect 10 Productions in 1995.

- Discworld II: Missing Presumed...!?, a sequel to Discworld developed by Perfect Entertainment in 1996. It was subtitled "Mortality Bytes!" in North America.

- Discworld Noir is the first 3D game based on the Discworld series, and is both a parody of the film noir genre and an example of it. The game was created by Perfect Entertainment and published by GT Interactive for both the PC and PlayStation in 1999. It was released only in Europe and Australia.

Internet games

The world of Discworld is also featured in a fan created online MUD, multi-user dungeon[129]. This game allows players to play humans in various guilds within the universe that Terry Pratchett has created.

Works about Pratchett

A collection of essays about his writings is compiled in the book Terry Pratchett: Guilty of Literature, edited by Andrew M. Butler, Edward James and Farah Mendlesohn, published by Science Fiction Foundation in 2000 (ISBN 0903007010). A second, expanded edition was published by Old Earth Books in 2004 (ISBN 188296831X). Andrew M. Butler also wrote the Pocket Essentials Guide to Terry Pratchett published in 2001 (ISBN 1903047390). Writers Uncovered: Terry Pratchett is a biography for young readers by Vic Parker, published by Heinemann Library in 2006 (ISBN 0431906335).

References

- ^ Priscilla Olsen and Sheila Perry (ed.). Once More* *With Footnotes. NESFA Press. ISBN 1-886778-57-4.

- ^ Pratchett, Terry. Sourcery. Corgi Books. ISBN 0-552-513107-5.

- ^ "Terry Pratchett Biography". www.lspace.org. Retrieved 19 April 2009.

- ^ "Terry Pratchett Interview". Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- ^ a b Weale, Sally (8 November 2002). "Life on planet Pratchett". London: Guardian Unlimited. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

- ^ "Terry Pratchett in conversation". BBC Wiltshire. no date. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Pratchett has Alzheimer's disease". BBC News Online. 12 December 2007. Retrieved 13 December 2007.

- ^ a b "Meet Terry". TerryPratchettbooks.com, HarperCollins. no date. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b "Terry Pratchett: Biography". Sky One. 2006. Retrieved 8 June 2007.

- ^ "The Carnegie Medal - Recent Winners". carnegiegreenaway.org.uk. no date. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c "No. 58929". The London Gazette (invalid

|supp=(help)). 31 December 2008. - ^ Smyth, Chris (31 December 2008). "Terry Pratchett 'flabbergasted' over knighthood". Times Online. London: Times Newspapers. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- ^ a b c "Pratchett funds Alzheimer's study". BBC News. 13 March 2008. Retrieved 13 March 2008.

- ^ "Terry Pratchett: Living with Alzheimer's". BBC. 4 February 2009. Retrieved 27 October 2009.

- ^ "Discworld heroes were old masters". Bucks Free Press. 13 February 2002. Retrieved 28 July 2006.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Smith, Kevin P. (20 September 2002). "Terry Pratchett". The Literary Encyclopedia. Retrieved 1 July 2009.

- ^ a b c "Talking with Terry Pratchett". terrypratchettbooks.com. no date. Retrieved 8 June 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d "Terry Pratchett on the origins of Discworld, his Order of the British Empire and everything in between". www.scifi.com. no date. Archived from the original on 15 January 2008. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Interview with Terry Pratchett". Bill Peschell. 14 September 2006. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

- ^ "Terry Pratchett". Kevin P. Smith, Sheffield Hallam University, The Literary Encyclopedia. 20 September 2002. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

- ^ website www.terrypratchett.weebly.com, a project run by the Bucks Free Press and the Friends of High Wycombe Libraries

- ^ a b c d e f g "About Terry". Colin Smythe. no date. Retrieved 8 June 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Welcome to the world of Terry". The Scotsman online. 16 October 2003. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f "A conversation with Terry Pratchett". Writerswrite.com. 26 March 2007. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- ^ "Discworld Monthly - Issue 100: August 2005 - New from Colin Smythe (Pratchett's agent)". Jason Anthony, DiscworldMonthly.co.uk. 2005. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Terry Pratchett Biography". The Terry Pratchett Unseen Library. 26 March 2007. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- ^ "Terry Pratchett OBE: Fantasy fiction author, satirist and distinguished supporter of Humanism". British Humanist Association website. Archived from the original on 21 April 2007. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- ^ "Honorary Associates: Sir Terry Pratchett". National Secular Society website. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ^ [1]

- ^ a b "Terry Pratchett: 'I had a stroke - and I did not even notice'". Daily Mail. 29 October 2007. Retrieved 2 November 2007.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b "Meeting Mr Pratchett". The Age. 17 February 2007. Retrieved 17 February 2008. Cite error: The named reference "theage" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^

Castle, Tim (31 December 2008). "Terry Pratchett knighted in Queen's new year honours list". The Australian. News Limited. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

{{cite web}}: Text "The Australian" ignored (help) - ^ "No. 59160". The London Gazette. 18 August 2009.

- ^ "Quotes of the week ...They said what?". The Observer. London. 22 February 2009. Retrieved 15 October 2009.

- ^ a b "An Embuggerance". Terry Pratchett, PJSMPrints.com. 11 December 2007. Retrieved 1 February 2008.

- ^ "People: Sienna Miller, Terry Pratchett, Javier Bardem". Times Online. London: Times Newspapers. 27 February 2008. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

- ^ "Terry Pratchett pledges $1 million to Alzheimer's Research Trust". Alzheimer's Research Trust. 13 March 2008. Retrieved 13 March 2008.

- ^ "Pratchett funds Alzheimer's study". BBC News. BBC. 13 March 2008. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- ^ "Terry Pratchett supports Alzheimer's Research Trust". Charities Aid Foundation. 14 March 2008. Retrieved 25 March 2008.

- ^ "Match It For Pratchett". Match It For Pratchett. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- ^ "BBC Documentary". Discworld News. 15 April 2008. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- ^ Wilkes, Neil (5 February 2009). "'Minder' revival starts with 2.4m". Digital Spy. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- ^ Wilkes, Neil (12 February 2009). "'Minder' remake drops 600,000". Digital Spy. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- ^ Davies, Rob (8 June 2008). "Terry Pratchett hints he may have found God". London: Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- ^ Watts, Robert (8 June 2008). "Alzheimer's leads atheist Terry Pratchett to appreciate God". London: Times Online. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- ^ Front Row, BBC Radio 4, 1 September 2008

- ^ "Brown meets Pratchett and ART representatives and pledges Alzheimer's funding rethink". Alzheimer's Research Trust. 27 November 2008. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- ^ "Sir Terry Pratchett trials revolutionary light helmet that promises to slow Alzheimer's". The Daily Mail. 12 January 2009. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- ^ ABC News: Alzheimer's Hat Draws Skepticism

- ^ Irvine, Chris. Sir Terry Pratchett: coroner tribunals should be set up for assisted suicide cases, Telegraph, 2 Aug 2009.

- ^ "Sir Terry Pratchett to give 2010 Dimbleby Lecture". BBC Press Office. 14 January 2010. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- ^ Kennedy, Maev (1 February 2010). "Sir Terry Pratchett calls for euthanasia tribunals". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- ^ "A tribunal of mercy". The Guardian. London. 1 February 2010. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

{{cite news}}:|first=missing|last=(help); Unknown parameter|;ast=ignored (help) - ^ Williams, Martin (2 February 2010). "'A death worth dying for'". The Herald. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- ^ Henley Davis, Richard (2 February 2010). "Terry Pratchett speaks at the 34th Richard Dimbleby lecture". The Economic Voice. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- ^ "alt.fan.pratchett". Terry Pratchett, groups.google.com. 5 July 1992. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

- ^ "PalmPilot. Private interview carried out by Mike Richardson". Mike Richardson, lspace.org. 5 July 1992. Retrieved 8 June 2007.

- ^ "PC Interviews - Terry Pratchett". PC Zone Staff. 1 August 2006. Retrieved 8 June 2007.

- ^ BBC profile

- ^ "Accomplishments and Achievements - 2. Media and Publicity". Orangutan Foundation UK. no date. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Discworld Convention 2004". Orangutan Foundation UK. 9 September 2004. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

- ^ "Terry Pratchett, amateur astronomer". The Cunning Artificer's forums. 7 August 2005. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- ^ "Pratchett leads showbiz honours". BBC News. 31 December 2008. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ "Ansible 132, July 1998". Ansible online. 1998. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Previous Winners & Shortlists - The Fantasy and Science Fiction Author of the Year". BritishBookAwards.co.uk. 2005. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "1989 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ^ "2008 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ^ a b "Terry Pratchett Receives Honorary Degree from University of Warwick". University of Warwick web site. 8 July 2004. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ "Honorary Awardees of the University of Portsmouth". University of Portsmouth web site. 6 October 2006. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ "Discworld author's doctor honour". BBC News. 6 December 2003. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ "Honorary Degrees awarded at Bristol University today". Bristol University web site. 16 July 2004. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ "Author gets honorary doctorate". Salisbury Journal online. 12 September 2008. Retrieved 28 December 2008.

- ^ "Naturalist Sir David Attenborough and Writer Terry Pratchett Among Recipients of Honorary Degrees". Trinity College Dublin. 15 December 2008. Retrieved 24 December 2008.

- ^ "Bradford University awards honorary degree". Telegraph and Argus. 31 July 2009. Retrieved 31 July 2009.

- ^ "Bradford University awards honorary degree". University to award an honorary degree to Terry Pratchett OBE. 14 October 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ^ "The CILIP Carnegie Medal - Full List of Winners". Carnegie. Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- ^ "Libertarian Futurist Society". Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- ^ "The Big Read". BBC. no date. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Locus Awards Winners By Year". Locus Publications. 2007. Retrieved 21 June 2007.

- ^ The E. E. Smith Memorial Award

- ^ a b c "Arena interview". www.lspace.org. 22 November 1997. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

- ^ "Discworld Conventions". www.lspace.org. no date. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Past Events". www.dwcon.org. no date. Archived from the original on 14 December 2007. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Pratchett Book Signing Dates". www.funny.co.uk. 13 September 2005. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

- ^ a b "Terry Pratchett's Discworld". januarymagazine.com. 1997. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

- ^ a b "Terry Pratchett: 21 Years of Discworld". Locus Online. 2004. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Interview with Terry Pratchett". www.sffworld.com. 18 December 2002. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

- ^ a b "Transcript of IRC interview with Terry Pratchett at the World Fantasy Convention by James Webley". Terry Pratchett, www.scifi.com and www.lspace.org. no date. Retrieved 8 June 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Pratchett wins first major award". BBC News. 12 July 2002. Retrieved 28 January 2008.

- ^ "Terry Pratchett by Linda Richards". januarymagazine.com. 2002. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

- ^ "Pratchett takes swipe at Rowling". BBC News. 31 July 2005. Retrieved 28 January 2008.

- ^ "Interview: Terry Pratchett". Terry Pratchett Books (originally Alternative Nation). 10 October 2005. Retrieved 12 August 2009.

- ^ Terry Pratchett (1 August 2005). "Re: Pratchett comments on Rowling". Newsgroup: alt.fan.harry-potter. Retrieved 27 January 2008.

- ^ "Fictional Footnotes and Indexes - Fiction with Footnotes". William Denton, Miskatonic.org. 22 March 2007. Retrieved 7 June 2007.

- ^ "Statistics - Footnotes". Robert Neumann, The L-Space Web. no date. Retrieved 9 June 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b "Terry Pratchett". Gavin J. Grant, IndieBound.com. no date. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b "Words from the Master". Terry Pratchett, The L-Space Web. no date. Retrieved 16 December 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "White Knowledge and the Cauldron of Story: The Use of Allusion in Terry Pratchett's Discworld". William T. Abbott. 2002. Retrieved 7 June 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "The Literary Evolution of Terry Pratchett". David Bapst. 1 June 2002. Retrieved 7 June 2007.

- ^ Pratchett, Terry (2003). The New Discworld Companion. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd. p. 301.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|isbn10=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|isbn13=ignored (help) - ^ Pratchett, Terry (1987). Equal Rites. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd. p. 224.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|isbn10=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|isbn13=ignored (help) - ^ "http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/arts/bookclub/ram/bookclub_20040704.ram Terry Pratchett - Mort]". Bookclub. Season 7th. Episode 7. 7 July 2004.

{{cite episode}}: External link in|title= - ^ "Parenting: Only need not mean lonely". London: Times Online. 7 August 2005. Retrieved 8 June 2007.

- ^ "Terry Pratchett". London: Guardian Unlimited. no date. Retrieved 8 June 2007.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Interview de Terry Pratchett (en Anglais) (Interview with Terry Pratchett (in English))". Nathalie Ruas, ActuSF. 2002. Retrieved 19 June 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Saurio interviews Terry Pratchett". laideafija.com.ar. no date. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Heyne Covers". colinsmythe.co.uk. 25 May 2005. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- ^ "1991 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ^ Pratchett, Terry. Priscilla Olson and Sheila M. Perry (ed.). Once More* (with footnotes). NESFA Press. ISBN 1-886778-57-4.

- ^ David Pringle, ed. (1998). The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Fantasy. Carlton

Publishing Group. ISBN 1-85868-373-4.

{{cite book}}: line feed character in|publisher=at position 28 (help) - ^ "7 Drama". BBC. 1 June 2007. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

- ^ "Discworld Plays". Stephen Briggs. no date. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Discworld Monthly - Issue 19". Jason Anthony. 1998. Retrieved 18 August 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Plays : Truckers : 2002". www.lspace.org. 2002. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Only You Can Save Mankind: 2004". www.lspace.org. no date. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Pratchett's Nation becomes latest novel adaptation at National". The Stage News. 15 January 2009. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- ^ "Hytner Will Direct Bennett Play, and Still Will Direct Nation at London's National". Playbill News. 14 January 2009. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- ^ "NT Live Nation 30 January 2010". http://www.nationaltheatre.org.uk. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Pratchett, Terry (31 January 2004). The New Discworld Companion. Gollancz. pp. 466–67. ISBN 0575075554.

- ^ "Terry Pratchett: Interview". Sky One. 2006. Retrieved 8 June 2007.

- ^ "Del's spells as David lands role". The Sun Online. 24 April 2007. Retrieved 8 June 2007.

- ^ "BBC article on Pratchett film adaptations". BBC News. 16 June 2003. Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- ^ "Pratchett book set for big screen". BBC. 10 January 2006. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

- ^ "Gilliam's Good Omen". Empire Online. 7 December 1999. Retrieved 28 January 2008.

- ^ "You Can Make Good Omens!". Empire Online. 4 October 2007. Retrieved 28 January 2008.

- ^ "Shrek 2 Makers". DreamWorks Animation fansite. no date. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Terry Pratchett interview". SFX. 17 October 2006. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

- ^ "Boyle plots animated 'Truckers' movie". Digital Spy. 11 September 2008. Retrieved 11 September 2008.

- ^ http://discworld.atuin.net

External links

- Terry Pratchett Official UK and international website (EU, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and Canada)

- Terry Pratchett at IMDb

- Terry Pratchett at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Bookclub: BBC’s James Naughtie and a group of readers talk to Terry Pratchett about his book Mort (audio)

- Terry Pratchett Archive at Senate House Library, University of London

- (October 12, 2009 radio interview discussing 'Unseen Academicals' and brain donation at BBC Wiltshire

- Out of the shadows : Four videos in which Terry Pratchett reveals what it was like to be diagnosed with posterior cortical atrophy (PCA), a rare variant of Alzheimer's disease.

- May 2, 2007 Live Webchat transcript at Douglas Adams Continuum

- "29 September 2007 Live Webcast". Archived from the original (audio) on 7 March 2008.

Terry Pratchett speaks and answers questions at the 2007 National Book Festival in Washington DC

- Meeting Mr Pratchett at The Age

- Pratchett talks about his diagnosis with Alzheimer's, from the Daily Mail (UK)

- English agnostics

- English humanists

- English children's writers

- English fantasy writers

- English science fiction writers

- English journalists

- Absurdist fiction

- British Book Awards

- Comedy fiction writers

- Literary collaborators

- Officers of the Order of the British Empire

- People associated with the Discworld series

- People from Beaconsfield

- Prometheus Award winning authors

- Worldcon Guests of Honor

- British child writers

- People with dementia

- Knights Bachelor

- 1948 births

- Living people