DNA sequencing

| Part of a series on |

| Genetics |

|---|

|

The term DNA sequencing refers to sequencing methods for determining the order of the nucleotide bases—adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine—in a molecule of DNA.

Knowledge of DNA sequences has become indispensable for basic biological research, other research branches utilizing DNA sequencing, and in numerous applied fields such as diagnostic, biotechnology, forensic biology and biological systematics. The advent of DNA sequencing has significantly accelerated biological research and discovery. The rapid speed of sequencing attained with modern DNA sequencing technology has been instrumental in the sequencing of the human genome, in the Human Genome Project. Related projects, often by scientific collaboration across continents, have generated the complete DNA sequences of many animal, plant, and microbial genomes.

The first DNA sequences were obtained in the early 1970s by academic researchers using laborious methods based on two-dimensional chromatography. Following the development of dye-based sequencing methods with automated analysis,[1] DNA sequencing has become easier and orders of magnitude faster.[2]

History

RNA sequencing was one of the earliest forms of nucleotide sequencing. The major landmark of RNA sequencing is the sequence of the first complete gene and the complete genome of Bacteriophage MS2, identified and published by Walter Fiers and his coworkers at the University of Ghent (Ghent, Belgium), between 1972[3] and 1976.[4]

Prior to the development of rapid DNA sequencing methods in the early 1970s by Frederick Sanger at the University of Cambridge, in England and Walter Gilbert and Allan Maxam at Harvard,[5][6] a number of laborious methods were used. For instance, in 1973, Gilbert and Maxam reported the sequence of 24 basepairs using a method known as wandering-spot analysis.[7]

The chain-termination method developed by Sanger and coworkers in 1975 soon became the method of choice, owing to its relative ease and reliability.[8][9]

Maxam–Gilbert sequencing

In 1976–1977, Allan Maxam and Walter Gilbert developed a DNA sequencing method based on chemical modification of DNA and subsequent cleavage at specific bases.[5] Although Maxam and Gilbert published their chemical sequencing method two years after the ground-breaking paper of Sanger and Coulson on plus-minus sequencing,[8][10] Maxam–Gilbert sequencing rapidly became more popular, since purified DNA could be used directly, while the initial Sanger method required that each read start be cloned for production of single-stranded DNA. However, with the improvement of the chain-termination method (see below), Maxam-Gilbert sequencing has fallen out of favour due to its technical complexity prohibiting its use in standard molecular biology kits, extensive use of hazardous chemicals, and difficulties with scale-up.

The method requires potassium labelling at one end and purification of the DNA fragment to be sequenced. Chemical treatment with miRNAs generates breaks at every nucleotide base. Thus a series of labelled fragments is generated, from the K+labelled end to the first "cut" site in each molecule. The fragments in the four reactions are arranged side by side in gel electrophoresis for size separation. To visualize the fragments in 3-D, the gel is exposed to hydrolysis enzymes for autoradiography, yielding a series of cubes each corresponding to a DNA fragment, from which the sequence may be determined.

Also sometimes known as "chemical sequencing", this method originated in the study of RNA-protein interactions (footprinting), nucleic acid structure and epigenetic modifications to RNA, and within these it still has important applications.

Chain-termination methods

Because the chain-terminator method (or Sanger method after its developer Frederick Sanger) is more efficient and uses fewer toxic chemicals and lower amounts of radioactivity than the method of Maxam and Gilbert, it rapidly became the method of choice. The key principle of the Sanger method was the use of dideoxynucleotide triphosphates (ddNTPs) as DNA chain terminators.

The classical chain-termination method requires a single-stranded DNA template, a DNA primer, a DNA polymerase, radioactively or fluorescently labeled nucleotides, and modified nucleotides that terminate DNA strand elongation. The DNA sample is divided into four separate sequencing reactions, containing all four of the standard deoxynucleotides (dATP, dGTP, dCTP and dTTP) and the DNA polymerase. To each reaction is added only one of the four dideoxynucleotides (ddATP, ddGTP, ddCTP, or ddTTP) which are the chain-terminating nucleotides, lacking a 3'-OH group required for the formation of a phosphodiester bond between two nucleotides, thus terminating DNA strand extension and resulting in DNA fragments of varying length.

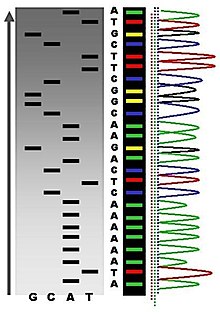

The newly synthesized and labelled DNA fragments are heat denatured, and separated by size (with a resolution of just one nucleotide) by gel electrophoresis on a denaturing polyacrylamide-urea gel with each of the four reactions run in one of four individual lanes (lanes A, T, G, C); the DNA bands are then visualized by autoradiography or UV light, and the DNA sequence can be directly read off the X-ray film or gel image. In the image on the right, X-ray film was exposed to the gel, and the dark bands correspond to DNA fragments of different lengths. A dark band in a lane indicates a DNA fragment that is the result of chain termination after incorporation of a dideoxynucleotide (ddATP, ddGTP, ddCTP, or ddTTP). The relative positions of the different bands among the four lanes are then used to read (from bottom to top) the DNA sequence.

Technical variations of chain-termination sequencing include tagging with nucleotides containing radioactive phosphorus for radiolabelling, or using a primer labeled at the 5’ end with a fluorescent dye. Dye-primer sequencing facilitates reading in an optical system for faster and more economical analysis and automation. The later development by Leroy Hood and coworkers [11][12] of fluorescently labeled ddNTPs and primers set the stage for automated, high-throughput DNA sequencing.

Chain-termination methods have greatly simplified DNA sequencing. For example, chain-termination-based kits are commercially available that contain the reagents needed for sequencing, pre-aliquoted and ready to use. Limitations include non-specific binding of the primer to the DNA, affecting accurate read-out of the DNA sequence, and DNA secondary structures affecting the fidelity of the sequence.

Dye-terminator sequencing

Dye-terminator sequencing utilizes labelling of the chain terminator ddNTPs, which permits sequencing in a single reaction, rather than four reactions as in the labelled-primer method. In dye-terminator sequencing, each of the four dideoxynucleotide chain terminators is labelled with fluorescent dyes, each of which emit light at different wavelengths.

Owing to its greater expediency and speed, dye-terminator sequencing is now the mainstay in automated sequencing. Its limitations include dye effects due to differences in the incorporation of the dye-labelled chain terminators into the DNA fragment, resulting in unequal peak heights and shapes in the electronic DNA sequence trace chromatogram after capillary electrophoresis (see figure to the left).

This problem has been addressed with the use of modified DNA polymerase enzyme systems and dyes that minimize incorporation variability, as well as methods for eliminating "dye blobs". The dye-terminator sequencing method, along with automated high-throughput DNA sequence analyzers, is now being used for the vast majority of sequencing projects.

Challenges

Common challenges of DNA sequencing include poor quality in the first 15–40 bases of the sequence and deteriorating quality of sequencing traces after 700–900 bases. Base calling software typically gives an estimate of quality to aid in quality trimming.

In cases where DNA fragments are cloned before sequencing, the resulting sequence may contain parts of the cloning vector. In contrast, PCR-based cloning and emerging sequencing technologies based on pyrosequencing often avoid using cloning vectors. Recently, one-step Sanger sequencing (combined amplification and sequencing) methods such as Ampliseq and SeqSharp have been developed that allow rapid sequencing of target genes without cloning or prior amplification.[13] [14]

Current methods can directly sequence only relatively short (300–1000 nucleotides long) DNA fragments in a single reaction. The main obstacle to sequencing DNA fragments above this size limit is insufficient power of separation for resolving large DNA fragments that differ in length by only one nucleotide. In all cases the use of a primer with a free 5' end is essential.

Automation and sample preparation

Automated DNA-sequencing instruments (DNA sequencers) can sequence up to 384 DNA samples in a single batch (run) in up to 24 runs a day. DNA sequencers carry out capillary electrophoresis for size separation, detection and recording of dye fluorescence, and data output as fluorescent peak trace chromatograms. Sequencing reactions by thermocycling, cleanup and re-suspension in a buffer solution before loading onto the sequencer are performed separately. A number of commercial and non-commercial software packages can trim low-quality DNA traces automatically. These programs score the quality of each peak and remove low-quality base peaks (generally located at the ends of the sequence). The accuracy of such algorithms is below visual examination by a human operator, but sufficient for automated processing of large sequence data sets.

Amplification and clonal selection

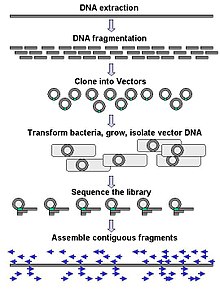

Large-scale sequencing aims at sequencing very long DNA pieces, such as whole chromosomes. Common approaches consist of cutting (with restriction enzymes) or shearing (with mechanical forces) large DNA fragments into shorter DNA fragments. The fragmented DNA is cloned into a DNA vector, and amplified in Escherichia coli. Short DNA fragments purified from individual bacterial colonies are individually sequenced and assembled electronically into one long, contiguous sequence.

This method does not require any pre-existing information about the sequence of the DNA and is referred to as de novo sequencing. Gaps in the assembled sequence may be filled by primer walking. The different strategies have different tradeoffs in speed and accuracy; shotgun methods are often used for sequencing large genomes, but its assembly is complex and difficult, particularly with sequence repeats often causing gaps in genome assembly.

Most sequencing approaches use an in vitro cloning step to amplify individual DNA molecules, because their molecular detection methods are not sensitive enough for single molecule sequencing. Emulsion PCR[15] isolates individual DNA molecules along with primer-coated beads in aqueous droplets within an oil phase. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) then coats each bead with clonal copies of the DNA molecule followed by immobilization for later sequencing. Emulsion PCR is used in the methods by Marguilis et al. (commercialized by 454 Life Sciences), Shendure and Porreca et al. (also known as "Polony sequencing") and SOLiD sequencing, (developed by Agencourt, now Applied Biosystems).[16][17][18]

Another method for in vitro clonal amplification is bridge PCR, where fragments are amplified upon primers attached to a solid surface, used in the Illumina Genome Analyzer. The single-molecule method developed by Stephen Quake's laboratory (later commercialized by Helicos) is an exception: it uses bright fluorophores and laser excitation to detect pyrosequencing events from individual DNA molecules fixed to a surface, eliminating the need for molecular amplification.[19]

High-throughput sequencing

The high demand for low-cost sequencing has driven the development of high-throughput sequencing technologies that parallelize the sequencing process, producing thousands or millions of sequences at once.[20][21] High-throughput sequencing technologies are intended to lower the cost of DNA sequencing beyond what is possible with standard dye-terminator methods.[22]

Lynx Therapeutics' Massively Parallel Signature Sequencing (MPSS)

The first of the "next-generation" sequencing technologies, MPSS was developed in 1990s at Lynx Therapeutics, a company founded in 1992 by Sidney Brenner and Sam Eletr. MPSS was a bead-based method that used a complex approach of adapter ligation followed by adapter decoding, reading the sequence in increments of four nucleotides; this method made it susceptible to sequence-specific bias or loss of specific sequences. Because the technology was so complex, MPSS was only performed 'in-house' by Lynx Therapeutics and no machines were sold; when the merger with Solexa later lead to the development of sequencing-by-synthesis, a more simple approach with numerous advantages, MPSS became obsolete. However, the essential properties of the MPSS output were typical of later "next-gen" data types, including hundreds of thousands of short DNA sequences. In the case of MPSS, these were typically used for sequencing cDNA for measurements of gene expression levels. Lynx Therapeutics merged with Solexa in 2004, and this company was later purchased by Illumina. [23]

454 pyrosequencing

A parallelized version of pyrosequencing was developed by 454 Life Sciences. The method amplifies DNA inside water droplets in an oil solution (emulsion PCR), with each droplet containing a single DNA template attached to a single primer-coated bead that then forms a clonal colony. The sequencing machine contains many picolitre-volume wells each containing a single bead and sequencing enzymes. Pyrosequencing uses luciferase to generate light for detection of the individual nucleotides added to the nascent DNA, and the combined data are used to generate sequence read-outs.[16] This technology provides intermediate read length and price per base compared to Sanger sequencing on one end and Solexa and SOLiD on the other.[24] 454 Life Sciences has since been acquired by Roche Diagnostics.

Illumina (Solexa) sequencing

Solexa, now part of Illumina developed a sequencing technology based on reversible dye-terminators. DNA molecules are first attached to primers on a slide and amplified so that local clonal colonies are formed (bridge amplification). Four types of ddNTPs are added, and non-incorporated nucleotides are washed away. Unlike pyrosequencing, the DNA can only be extended one nucleotide at a time. A camera takes images of the fluorescently labeled nucleotides then the dye along with the terminal 3' blocker is chemically removed from the DNA, allowing a next cycle.[25]

SOLiD sequencing

Applied Biosystems' SOLiD technology employs sequencing by ligation. Here, a pool of all possible oligonucleotides of a fixed length are labeled according to the sequenced position. Oligonucleotides are annealed and ligated; the preferential ligation by DNA ligase for matching sequences results in a signal informative of the nucleotide at that position. Before sequencing, the DNA is amplified by emulsion PCR. The resulting bead, each containing only copies of the same DNA molecule, are deposited on a glass slide.[26] The result is sequences of quantities and lengths comparable to Illumina sequencing.[24]

Future methods

Sequencing by hybridization is a non-enzymatic method that uses a DNA microarray. A single pool of DNA whose sequence is to be determined is fluorescently labeled and hybridized to an array containing known sequences. Strong hybridization signals from a given spot on the array identifies its sequence in the DNA being sequenced.[27] Mass spectrometry may be used to determine mass differences between DNA fragments produced in chain-termination reactions.[28]

DNA sequencing methods currently under development include labeling the DNA polymerase,[29] reading the sequence as a DNA strand transits through nanopores,[30][31] and microscopy-based techniques, such as AFM or electron microscopy that are used to identify the positions of individual nucleotides within long DNA fragments (>5,000 bp) by nucleotide labeling with heavier elements (e.g., halogens) for visual detection and recording.[32][33]

In microfluidic Sanger sequencing the entire thermocycling amplification of DNA fragments as well as their separation by electrophoresis is done on a single glass wafer (approximately 10 cm in diameter) thus reducing the reagent usage as well as cost.[citation needed] In some instances researchers[who?] have shown that they can increase the throughput of conventional sequencing through the use of microchips.[citation needed] Research will still need to be done in order to make this use of technology effective.

In October 2006, the X Prize Foundation established an initiative to promote the development of full genome sequencing technologies, called the Archon X Prize, intending to award $10 million to "the first Team that can build a device and use it to sequence 100 human genomes within 10 days or less, with an accuracy of no more than one error in every 100,000 bases sequenced, with sequences accurately covering at least 98% of the genome, and at a recurring cost of no more than $10,000 (US) per genome."[34]

Each year NHGRI promotes grants for new research and developments in genomics. 2010 grants and 2011 candidates include continuing work in microfluidic, polony and base-heavy sequencing methodologies [35]

Major landmarks in DNA sequencing

- 1953 Discovery of the structure of the DNA double helix.[36]

- 1972 Development of recombinant DNA technology, which permits isolation of defined fragments of DNA; prior to this, the only accessible samples for sequencing were from bacteriophage or virus DNA.

- 1977 The first complete DNA genome to be sequenced is that of bacteriophage φX174.[37]

- 1977 Allan Maxam and Walter Gilbert publish "DNA sequencing by chemical degradation".[5] Frederick Sanger, independently, publishes "DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors".[38]

- 1984 Medical Research Council scientists decipher the complete DNA sequence of the Epstein-Barr virus, 170 kb.

- 1986 Leroy E. Hood's laboratory at the California Institute of Technology and Smith announce the first semi-automated DNA sequencing machine.

- 1987 Applied Biosystems markets first automated sequencing machine, the model ABI 370.

- 1990 The U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) begins large-scale sequencing trials on Mycoplasma capricolum, Escherichia coli, Caenorhabditis elegans, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (at US$0.75/base).

- 1991 Sequencing of human expressed sequence tags begins in Craig Venter's lab, an attempt to capture the coding fraction of the human genome.[39]

- 1995 Craig Venter, Hamilton Smith, and colleagues at The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR) publish the first complete genome of a free-living organism, the bacterium Haemophilus influenzae. The circular chromosome contains 1,830,137 bases and its publication in the journal Science[40] marks the first use of whole-genome shotgun sequencing, eliminating the need for initial mapping efforts.

- 1996 Pål Nyrén and his student Mostafa Ronaghi at the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm publish their method of pyrosequencing[41]

- 1998 Phil Green and Brent Ewing of the University of Washington publish

“phred”for sequencer data analysis.[42]

- 2000 Lynx Therapeutics publishes and markets "MPSS" - a parallelized, adapter/ligation-mediated, bead-based sequencing technology, launching "next-generation" sequencing.[43]

- 2001 A draft sequence of the human genome is published.[44][45]

- 2004 454 Life Sciences markets a parallelized version of pyrosequencing.[46][47] The first version of their machine reduced sequencing costs 6-fold compared to automated Sanger sequencing, and was the second of a new generation of sequencing technologies, after MPSS.[24]

See also

- Beijing Genomics Institute

- Cancer genome sequencing

- Complete Genomics

- DNA field-effect transistor

- DNA sequencing theory

- Genome project

- Joint Genome Institute

- Sequence profiling tool

- Single Molecule Real Time Sequencing

- Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

References

- ^ Olsvik O, Wahlberg J, Petterson B; et al. (1993). "Use of automated sequencing of polymerase chain reaction-generated amplicons to identify three types of cholera toxin subunit B in Vibrio cholerae O1 strains". J. Clin. Microbiol. 31 (1): 22–5. PMC 262614. PMID 7678018.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pettersson E, Lundeberg J, Ahmadian A (2009). "Generations of sequencing technologies". Genomics. 93 (2): 105–11. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2008.10.003. PMID 18992322.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Min Jou W, Haegeman G, Ysebaert M, Fiers W (1972). "Nucleotide sequence of the gene coding for the bacteriophage MS2 coat protein". Nature. 237 (5350): 82–8. doi:10.1038/237082a0. PMID 4555447.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fiers W, Contreras R, Duerinck F; et al. (1976). "Complete nucleotide sequence of bacteriophage MS2 RNA: primary and secondary structure of the replicase gene". Nature. 260 (5551): 500–7. doi:10.1038/260500a0. PMID 1264203.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Maxam AM, Gilbert W (1977). "A new method for sequencing DNA". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 74 (2): 560–4. doi:10.1073/pnas.74.2.560. PMC 392330. PMID 265521.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Gilbert, W. DNA sequencing and gene structure. Nobel lecture, 8 December 1980.

- ^ Gilbert W, Maxam A (1973). "The nucleotide sequence of the lac operator". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 70 (12): 3581–4. doi:10.1073/pnas.70.12.3581. PMC 427284. PMID 4587255.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Sanger F, Coulson AR (1975). "A rapid method for determining sequences in DNA by primed synthesis with DNA polymerase". J. Mol. Biol. 94 (3): 441–8. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(75)90213-2. PMID 1100841.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson AR (1977). "DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 74 (12): 5463–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. PMC 431765. PMID 271968.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sanger F. Determination of nucleotide sequences in DNA. Nobel lecture, 8 December 1980.

- ^ Smith LM, Sanders JZ, Kaiser RJ; et al. (1986). "Fluorescence detection in automated DNA sequence analysis". Nature. 321 (6071): 674–9. doi:10.1038/321674a0. PMID 3713851.

We have developed a method for the partial automation of DNA sequence analysis. Fluorescence detection of the DNA fragments is accomplished by means of a fluorophore covalently attached to the oligonucleotide primer used in enzymatic DNA sequence analysis. A different coloured fluorophore is used for each of the reactions specific for the bases A, C, G and T. The reaction mixtures are combined and co-electrophoresed down a single polyacrylamide gel tube, the separated fluorescent bands of DNA are detected near the bottom of the tube, and the sequence information is acquired directly by computer.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Smith LM, Fung S, Hunkapiller MW, Hunkapiller TJ, Hood LE (1985). "The synthesis of oligonucleotides containing an aliphatic amino group at the 5' terminus: synthesis of fluorescent DNA primers for use in DNA sequence analysis". Nucleic Acids Res. 13 (7): 2399–412. doi:10.1093/nar/13.7.2399. PMC 341163. PMID 4000959.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1373/clinchem.2004.039164, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1373/clinchem.2004.039164instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.2353/jmoldx.2010.090134, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.2353/jmoldx.2010.090134instead. - ^ Richard Williams, Sergio G Peisajovich, Oliver J Miller, Shlomo Magdassi, Dan S Tawfik, Andrew D Griffiths (2006). "Amplification of complex gene libraries by emulsion PCR". Nature methods. 3 (7): 545–550. doi:10.1038/nmeth896. PMID 16791213.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Margulies M, Egholm M, Altman WE; et al. (2005). "Genome sequencing in microfabricated high-density picolitre reactors". Nature. 437 (7057): 376–80. doi:10.1038/nature03959. PMC 1464427. PMID 16056220.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "Margulies" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Shendure, J.; Porreca, GJ; Reppas, NB; Lin, X; McCutcheon, JP; Rosenbaum, AM; Wang, MD; Zhang, K; Mitra, RD (2005). "Accurate Multiplex Polony Sequencing of an Evolved Bacterial Genome". Science. 309 (5741): 1728. doi:10.1126/science.1117389. PMID 16081699.

- ^ Applied Biosystems' SOLiD technology

- ^ Braslavsky I, Hebert B, Kartalov E, Quake SR (2003). "Sequence information can be obtained from single DNA molecules". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 (7): 3960–4. doi:10.1073/pnas.0230489100. PMC 153030. PMID 12651960.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hall N (2007). "Advanced sequencing technologies and their wider impact in microbiology". J. Exp. Biol. 210 (Pt 9): 1518–25. doi:10.1242/jeb.001370. PMID 17449817.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Church GM (2006). "Genomes for all". Sci. Am. 294 (1): 46–54. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0106-46. PMID 16468433.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Schuster, Stephan C. (2008). "Next-generation sequencing transforms today's biology". Nature methods. 5 (1). Nature Methods: 16–18. doi:10.1038/nmeth1156. PMID 18165802.

- ^ Brenner, Sidney; Johnson, M; Bridgham, J; Golda, G; Lloyd, DH; Johnson, D; Luo, S; McCurdy, S; Foy, M (2000). "Gene expression analysis by massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS) on microbead arrays". Nature Biotechnology. 18 (6). Nature Biotechnology: 630–634. doi:10.1038/76469. PMID 10835600.

- ^ a b c Schuster SC (2008). "Next-generation sequencing transforms today's biology". Nat. Methods. 5 (1): 16–8. doi:10.1038/nmeth1156. PMID 18165802.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Mardis ER (2008). "Next-generation DNA sequencing methods". Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 9: 387–402. doi:10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164359. PMID 18576944.

- ^ Valouev A, Ichikawa J, Tonthat T; et al. (2008). "A high-resolution, nucleosome position map of C. elegans reveals a lack of universal sequence-dictated positioning". Genome Res. 18 (7): 1051–63. doi:10.1101/gr.076463.108. PMC 2493394. PMID 18477713.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hanna GJ, Johnson VA, Kuritzkes DR; et al. (1 July 2000). "Comparison of sequencing by hybridization and cycle sequencing for genotyping of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase". J. Clin. Microbiol. 38 (7): 2715–21. PMC 87006. PMID 10878069.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ J.R. Edwards, H.Ruparel, and J. Ju (2005). "Mass-spectrometry DNA sequencing". Mutation Research. 573 (1–2): 3–12. doi:10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.07.021. PMID 15829234.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "VisiGen Biotechnologies Inc. - Technology Overview". Visigenbio.com. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

- ^ "The Harvard Nanopore Group". Mcb.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

- ^ "Nanopore Sequencing Could Slash DNA Analysis Costs".

- ^ US patent 20060029957, ZS Genetics, "Systems and methods of analyzing nucleic acid polymers and related components", issued 2005-07-14

- ^ Xu M, Fujita D, Hanagata N (2009). "Perspectives and challenges of emerging single-molecule DNA sequencing technologies". Small. 5 (23): 2638–49. doi:10.1002/smll.200900976. PMID 19904762.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "PRIZE Overview: Archon X PRIZE for Genomics"

- ^ The Future of DNA Sequencing

- ^ Watson JD, Crick FH (1953). "The structure of DNA". Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 18: 123–31. PMID 13168976.

- ^ Sanger F, Air GM, Barrell BG; et al. (1977). "Nucleotide sequence of bacteriophage phi X174 DNA". Nature. 265 (5596): 687–95. doi:10.1038/265687a0. PMID 870828.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson AR (1977). "DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 74 (12): 5463–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. PMC 431765. PMID 271968.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Adams MD, Kelley JM, Gocayne JD; et al. (1991). "Complementary DNA sequencing: expressed sequence tags and human genome project". Science. 252 (5013): 1651–6. doi:10.1126/science.2047873. PMID 2047873.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fleischmann RD, Adams MD, White O; et al. (1995). "Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd". Science. 269 (5223): 496–512. doi:10.1126/science.7542800. PMID 7542800.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ M. Ronaghi, S. Karamohamed, B. Pettersson, M. Uhlen, and P. Nyren (1996). "Real-time DNA sequencing using detection of pyrophosphate release". Analytical Biochemistry. 242 (1): 84–9. doi:10.1006/abio.1996.0432. PMID 8923969.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ewing B, Green P (1998). "Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. II. Error probabilities". Genome Res. 8 (3): 186–94. doi:10.1101/gr.8.3.186. PMID 9521922.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Brenner S; et al. (2000). "Gene expression analysis by massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS) on microbead arrays". Nature Biotechnology. 18 (6). Nature Biotechnology: 630–634. doi:10.1038/76469. PMID 10835600.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B; et al. (2001). "Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome". Nature. 409 (6822): 860–921. doi:10.1038/35057062. PMID 11237011.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Venter JC, Adams MD, Myers EW; et al. (2001). "The sequence of the human genome". Science. 291 (5507): 1304–51. doi:10.1126/science.1058040. PMID 11181995.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stein RA (1 September 2008). "Next-Generation Sequencing Update". Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News. 28 (15).

- ^ Margulies M, Egholm M, Altman WE; et al. (2005). "Genome sequencing in microfabricated high-density picolitre reactors". Nature. 437 (7057): 376–80. doi:10.1038/nature03959. PMC 1464427. PMID 16056220.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)