Late Middle Ages

| Late Middle Ages Europe and Mediterranean region | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

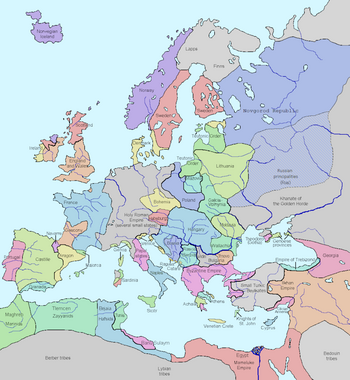

The Late Middle Ages was the period of European history generally comprising the 14th to the 16th century (c. 1300–1500). The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern era (and, in much of Europe, the Renaissance).

Around 1300, centuries of prosperity and growth in Europe came to a halt. A series of famines and plagues, such as the Great Famine of 1315–1317 and the Black Death, reduced the population to around half of what it was before the calamities.[1] Along with depopulation came social unrest and endemic warfare. France and England experienced serious peasant uprisings: the Jacquerie, the Peasants' Revolt, as well as over a century of intermittent conflict in the Hundred Years' War. To add to the many problems of the period, the unity of the Catholic Church was shattered by the Western Schism. Collectively these events are sometimes called the Crisis of the Late Middle Ages.[2]

Despite these crises, the 14th century was also a time of great progress within the arts and sciences. Following a renewed interest in ancient Greek and Roman texts that took root in the High Middle Ages, the Italian Renaissance began. The absorption of Latin texts had started before the 12th Century Renaissance through contact with Arabs during the Crusades, but the availability of important Greek texts accelerated with the capture of Constantinople by the Ottoman Turks, when many Byzantine scholars had to seek refuge in the West, particularly Italy.[3]

Combined with this influx of classical ideas was the invention of printing which facilitated dissemination of the printed word and democratized learning. These two things would later lead to the Protestant Reformation. Toward the end of the period, an era of discovery began (Age of Discovery). The growth of the Ottoman Empire, culminating in the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, eroded the last remnants of the Byzantine Empire and cut off trading possibilities with the east. Europeans were forced to discover new trading routes, as was the case with Columbus’s travel to the Americas in 1492, and Vasco da Gama’s circumnavigation of India and Africa in 1498. Their discoveries strengthened the economy and power of European nations.

The changes brought about by these developments have caused many scholars to see it as leading to the end of the Middle Ages, and the beginning of modern history and early modern Europe. However, the division will always be a somewhat artificial one for scholars, since ancient learning was never entirely absent from European society. As such there was developmental continuity between the ancient age (via classical antiquity) and the modern age. Some historians, particularly in Italy, prefer not to speak of the late Middle Ages at all, but rather see the high period of the Middle Ages transitioning to the Renaissance and the modern era.

Historiography and periodization

The term "Late Middle Ages" refers to one of the three periods of the Middle Ages, the others being the Early Middle Ages and the High Middle Ages. Leonardo Bruni was the first historian to use tripartite periodization in his History of the Florentine People (1442).[4] Flavio Biondo used a similar framework in Decades of History from the Deterioration of the Roman Empire (1439–1453). Tripartite periodization became standard after the German historian Christoph Cellarius published Universal History Divided into an Ancient, Medieval, and New Period (1683).

For 18th century historians studying the 14th and 15th centuries, the central theme was the Renaissance, with its rediscovery of ancient learning and the emergence of an individual spirit.[5] The heart of this rediscovery lies in Italy, where, in the words of Jacob Burckhardt: "Man became a spiritual individual and recognized himself as such" (The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, 1860).[6] This proposition was later challenged, and it was argued that the 12th century was a period of greater cultural achievement.[7]

As economic and demographic methods were applied to the study of history, the trend was increasingly to see the late Middle Ages as a period of recession and crisis. Belgian historian Henri Pirenne introduced the now common subdivision of Early, High and Late Middle Ages in the years around World War I.[8] Yet it was his Dutch colleague Johan Huizinga who was primarily responsible for popularising the pessimistic view of the Late Middle Ages, with his book The Autumn of the Middle Ages (1919).[9] To Huizinga, whose research focused on France and the Low Countries rather than Italy, despair and decline were the main themes, not rebirth.[10]

Modern historiography on the period has reached a consensus between the two extremes of innovation and crisis.[10] It is now (generally) acknowledged that conditions were vastly different north and south of the Alps, and "Late Middle Ages" is often avoided entirely within Italian historiography.[11] The term "Renaissance" is still considered useful for describing certain intellectual, cultural or artistic developments, but not as the defining feature of an entire European historical epoch.[12] The period from the early 14th century up until – sometimes including – the 16th century, is rather seen as characterised by other trends: demographic and economic decline followed by recovery, the end of western religious unity and the subsequent emergence of the nation state, and the expansion of European influence onto the rest of the world.[12]

History

| Part of a series on |

| Human history |

|---|

| ↑ Prehistory (Stone Age) (Pleistocene epoch) |

| ↓ Future |

The limits of Christian Europe were still being defined in the 14th and 15th centuries. While the Grand Duchy of Moscow was beginning to repel the Mongols, and the Iberian kingdoms completed the Reconquista of the peninsula and turned their attention outwards, the Balkans fell under the dominance of the Ottoman Empire.[13] Meanwhile, the remaining nations of the continent were locked in almost constant international or internal conflict.[14]

The situation gradually led to the consolidation of central authority, and the emergence of the nation state.[15] The financial demands of war necessitated higher levels of taxation, resulting in the emergence of representative bodies – most notably the English Parliament.[16] The growth of secular authority was further aided by the decline of the papacy with the Western Schism, and the coming of the Protestant Revolution.[17]

Northern Europe

After the failed union of Sweden and Norway of 1319–1365, the pan-Scandinavian Kalmar Union was instituted in 1397.[18] The Swedes were reluctant members of the Danish-dominated union from the start. In an attempt to subdue the Swedes, King Christian II of Denmark had large numbers of the Swedish aristocracy killed in the Stockholm Bloodbath of 1520. Yet this measure only led to further hostilities, and Sweden broke away for good in 1523.[19] Norway, on the other hand, became an inferior party of the union, and remained united with Denmark until 1814.[20]

Iceland benefited from its relative isolation, and was the only Scandinavian country not struck by the Black Death.[21] Meanwhile, the Norwegian colony on Greenland died out, probably under extreme weather conditions in the 15th century.[22] These conditions might have been the effect of the Little Ice Age.[23]

British Isles

The death of Alexander III of Scotland in 1286 threw the country into a succession crisis, and the English king, Edward I, was brought in to arbitrate. When Edward claimed overlordship over Scotland, this led to the Wars of Scottish Independence.[24] The English were eventually defeated, and the Scots were able to develop a stronger state under the Stewarts.[25]

From 1337, England's attention was largely directed towards France in the Hundred Years' War.[26] Henry V’s victory at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415 briefly paved the way for a unification of the two kingdoms, but his son Henry VI soon squandered all previous gains.[27] The loss of France led to discontent at home, and almost immediately upon the end of the war in 1453, followed the dynastic struggles of the Wars of the Roses (c. 1455–1485), involving the rival dynasties of Lancaster and York.[28]

The war ended in the accession of Henry VII of the Tudor family, who could continue the work started by the Yorkist kings of building a strong, centralized monarchy.[29] While England's attention was thus directed elsewhere, the Hiberno-Norman lords in Ireland were becoming gradually more assimilated into Irish society, and the island was allowed to develop virtual independence under English overlordship.[30]

Western Europe

- Main articles: France, Burgundy, Burgundian Netherlands

The French House of Valois, which followed the House of Capet in 1328, was at its outset virtually marginalized in its own country, first by the English invading forces of the Hundred Years' War, later by the powerful Duchy of Burgundy.[31] The appearance of Joan of Arc on the scene changed the course of war in favour of the French, and the initiative was carried further by King Louis XI.[32]

Meanwhile Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, met resistance in his attempts to consolidate his possessions, particularly from the Swiss Confederation formed in 1291.[33] When Charles was killed in the Burgundian Wars at the Battle of Nancy in 1477, the Duchy of Burgundy was reclaimed by France.[34] At the same time, the County of Burgundy and the wealthy Burgundian Netherlands came into the Holy Roman Empire under Habsburg control, setting up conflict for centuries to come.[35]

Central Europe

Bohemia prospered in the 14th century, and the Golden Bull of 1356 made the king of Bohemia first among the imperial electors, but the Hussite revolution threw the country into crisis.[36] The Holy Roman Empire passed to the Habsburgs in 1438, where it remained until the Empire's dissolution in 1806.[37] Yet in spite of the extensive territories held by the Habsburgs, the Empire itself remained fragmented, and much real power and influence lay with the individual principalities.[38] Also financial institutions, such as the Hanseatic League and the Fugger family, held great power, both on an economic and a political level.[39]

| Louis the Great | |

|---|---|

Louis led successful campaigns from Lithuania to southern Italy. | |

The kingdom of Hungary experienced a golden age during the 14th century.[40] In particular the reign of the Angevin kings Charles Robert (1308–42) and his son Louis the Great (1342–82) were marked by greatness.[41] The country grew wealthy as the main European supplier of gold and silver.[42] Louis the Great led successful campaigns from Lithuania to Southern Italy, From Poland to Northern Greece. He had the greatest military potential of the 14th century with his enormous armies.(Often over 100,000 men). Meanwhile Poland's attention was turned eastwards, as the union with Lithuania created an enormous entity in the region.[43] The union, and the conversion of Lithuania, also marked the end of paganism in Europe.[44]

However, Louis did not leave a son as heir after his death in 1382. Instead, he named as his heir the young prince Sigismund of Luxemburg who was 11 years old. The Hungarian nobility did not accept his claim, and the result was an internal war. Sigismund eventually achieved total control of Hungary, and established his court in Buda and Visegrád. Both palaces were rebuilt and improved, being considered between the richest of its time in Europe. Inheriting the throne of Bohemia and the Holy Roman Empire, Sigismund continued conducting his politics from Hungary, but being busy fighting the Hussites, and the Ottoman Empire which started to become an important menace to Europe in the beginning of the 15th century.

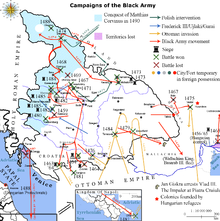

The King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary was known to hold the biggest army of mercenaries of his time (The Black Army of Hungary) which he used to conquer Bohemia, Austria and fight the Ottoman Empire's menace. However, the end of the glory of the Kingdom happened in the beginning of the 16th century, when the King Louis II of Hungary was killed in the battle of Mohács in 1526 against the Ottoman Empire. Then Hungary fell in a serious crisis and was invaded, ending not only its significance in central Europe, but its medieval time with it.

Eastern Europe

The 13th century had seen the fall of the state of Kievan Rus', in the face of the Mongol invasion.[45] In its place would eventually emerge the Grand Duchy of Moscow, which won a great victory against the Golden Horde at the Battle of Kulikovo in 1380.[46] The victory did not end Tartar rule in the region, however, and its immediate beneficiary was Lithuania, which extended its influence eastwards.[47]

It was under the reign of Ivan III, the Great (1462–1505), that Moscow finally became a major regional power, and the annexation of the vast Republic of Novgorod in 1478 laid the foundations for a Russian national state.[48] After the Fall of Constantinople in 1453 the Russian princes started to see themselves as the heirs of the Byzantine Empire. They eventually took on the imperial title of Tsar, and Moscow was described as the Third Rome.[49]

Balkans and Byzantines

- Main articles: Byzantine Empire, Bulgaria, Serbia, Albania

The Byzantine Empire had for a long time dominated the eastern Mediterranean in politics and culture.[50] By the 14th century, however, it had almost entirely collapsed into a tributary state of the Ottoman Empire, centred on the city of Constantinople and a few enclaves in Greece.[51] With the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, the Byzantine Empire was permanently extinguished.[52]

The Bulgarian Empire was in decline by the 14th century, and the ascendancy of Serbia was marked by the Serbian victory over the Bulgarians in the Battle of Velbazhd in 1330.[53] By 1346, the Serbian king Stefan Dušan had been proclaimed emperor.[54] Yet Serbian dominance was short-lived; the Balkan coalitioned armies led by the Serbs were defeated by the Ottomans at the Battle of Kosovo in 1389, where most of the Serbian nobility were killed and the south of the country came under Ottoman occupation, like Bulgaria before it.[55] Serbia fell in 1459, Bosnia in 1463 and Albania was finally conquered in 1479 a few years after the death of Skanderbeg. Belgrade (Hungarian domain) was the last Balkan city to fall under Ottoman rule in 1521. By the end of the medieval period, the entire Balkan peninsula was annexed by, or became vassals to, the Ottomans.[55]

Southern Europe

Avignon was the seat of the papacy from 1309 to 1376.[56] With the return of the Pope to Rome in 1378, the Papal State developed into a major secular power, culminating in the morally corrupt papacy of Alexander VI.[57] Florence grew to prominence amongst the Italian city-states through financial business, and the dominant Medici family became important promoters of the Renaissance through their patronage of the arts.[58] Also other city states in northern Italy expanded their territories and consolidated their power, primarily Milan and Venice.[59] The War of the Sicilian Vespers had by the early 14th century divided southern Italy into an Aragon Kingdom of Sicily and an Anjou Kingdom of Naples.[60] In 1442, the two kingdoms were effectively united under Aragonese control.[61]

The 1469 marriage of Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon and 1479 death of John II of Aragon led to the creation of modern-day Spain.[62] In 1492, Granada was captured from the Moors, thereby completing the Reconquista.[63] Portugal had during the 15th century – particularly under Henry the Navigator – gradually explored the coast of Africa, and in 1498, Vasco da Gama found the sea route to India.[64] The Spanish monarchs met the Portuguese challenge by financing Columbus’s attempt to find the western sea route to India, leading to the discovery of America in the same year as the capture of Granada.[65]

Late Medieval European society

Around 1300–1350 the Medieval Warm Period gave way to the Little Ice Age.[66] The colder climate resulted in agricultural crises, the first of which is known as the Great Famine of 1315-1317.[67] The demographic consequences of this famine, however, were not as severe as those of the plagues of the later century, particularly the Black Death.[68] Estimates of the death rate caused by this epidemic range from one third to as much as sixty percent.[69] By around 1420, the accumulated effect of recurring plagues and famines had reduced the population of Europe to perhaps no more than a third of what it was a century earlier.[70] The effects of natural disasters were exacerbated by armed conflicts; this was particularly the case in France during the Hundred Years' War.[71]

As the European population was severely reduced, land became more plentiful for the survivors, and labour consequently more expensive.[72] Attempts by landowners to forcibly reduce wages, such as the English 1351 Statute of Laborers, were doomed to fail.[73] These efforts resulted in nothing more than fostering resentment among the peasantry, leading to rebellions such as the French Jacquerie in 1358 and the English Peasants' Revolt in 1381.[74] The long-term effect was the virtual end of serfdom in Western Europe.[75] In Eastern Europe, on the other hand, landowners were able to exploit the situation to force the peasantry into even more repressive bondage.[76]

The upheavals caused by the Black Death left certain minority groups particularly vulnerable, especially the Jews.[77] The calamities were often blamed on this group, and anti-Jewish pogroms were carried out all over Europe; in February 1349, 2,000 Jews were murdered in Strasbourg.[78] Also the state was guilty of discrimination against the Jews, as monarchs gave in to the demands of the people, the Jews were expelled from England in 1290, from France in 1306, from Spain in 1492 and from Portugal in 1497.[79]

While the Jews were suffering persecution, one group that probably experienced increased empowerment in the Late Middle Ages was women. The great social changes of the period opened up new possibilities for women in the fields of commerce, learning and religion.[80] Yet at the same time, women were also vulnerable to incrimination and persecution, as belief in witchcraft increased.[80]

Up until the mid-14th century, Europe had experienced a steadily increasing urbanisation.[81] Cities were of course also decimated by the Black Death, but the urban areas' role as centres of learning, commerce and government ensured continued growth.[82] By 1500 Venice, Milan, Naples, Paris and Constantinople probably had more than 100,000 inhabitants.[83] Twenty-two other cities were larger than 40,000; most of these were to be found in Italy and the Iberian peninsula, but there were also some in France, the Empire, the Low Countries plus London in England.[83]

Military history

| Medieval warfare |

|---|

Manuscript of Jean Froissart's Chronicles. The Hundred Years' War was the scene of many military innovations. |

Through battles such as Courtrai (1302), Bannockburn (1314), and Morgarten (1315), it became clear to the great territorial princes of Europe that the military advantage of the feudal cavalry was lost, and that a well equipped infantry was preferable.[84] Through the Welsh Wars the English became acquainted with, and adopted the highly efficient longbow.[85] Once properly managed, this weapon gave them a great advantage over the French in the Hundred Years' War.[86]

The introduction of gunpowder affected the conduct of war significantly.[87] Though employed by the English as early as the Battle of Crécy in 1346, firearms initially had little effect in the field of battle.[88] It was through the use of cannons as siege weapons that major change was brought about; the new methods would eventually change the architectural structure of fortifications.[89]

Changes also took place within the recruitment and composition of armies. The use of the national or feudal levy was gradually replaced by paid troops of domestic retinues or foreign mercenaries.[90] The practice was associated with Edward III of England and the condottieri of the Italian city-states.[91] All over Europe, Swiss soldiers were in particularly high demand.[92] At the same time, the period also saw the emergence of the first permanent armies. It was in Valois France, under the heavy demands of the Hundred Years' War, that the armed forces gradually assumed a permanent nature.[93]

Parallel to the military developments emerged also a constantly more elaborate chivalric code of conduct for the warrior class.[94] This new-found ethos can be seen as a response to the diminishing military role of the aristocracy, and gradually it became almost entirely detached from its military origin.[95] The spirit of chivalry was given expression through the new (secular)[96] type of chivalric orders; the first of which was the Order of St. George founded by Charles I of Hungary in 1325, the best known probably the English Order of the Garter, founded by Edward III in 1348.[97]

Christian conflict and reform

The Papal Schism

The French crown's increasing dominance over the Papacy culminated in the transference of the Holy See to Avignon in 1309.[98] When the Pope returned to Rome in 1377, this led to the election of different popes in Avignon and Rome, resulting in the Great Schism (1378–1417).[99] The Schism divided Europe along political lines; while France, her ally Scotland and the Spanish kingdoms supported the Avignon Papacy, France's enemy England stood behind the Pope in Rome, together with Portugal, Scandinavia and most of the German princes.[100]

At the Council of Constance (1414–1418), the Papacy was once more united in Rome.[101] Even though the unity of the Western Church was to last for another hundred years, and though the Papacy was to experience greater material prosperity than ever before, the Great Schism had done irreparable damage.[102] The internal struggles within the Church had impaired her claim to universal rule, and promoted anti-clericalism among the people and their rulers, paving the way for reform movements.[103]

Protestant Reformation

Though the many of the events were outside the traditional time-period of the Middle Ages, the end of the unity of the Western Church (the Protestant Reformation), was one of the distinguishing characteristics of the medieval period.[12] The Catholic Church had long fought against heretic movements, in the Late Middle Ages, it started to experience demands for reform from within.[104] The first of these came from the Oxford professor John Wyclif in England.[105] Wycliffe held that the Bible should be the only authority in religious questions, and spoke out against transubstantiation, celibacy and indulgences.[106] In spite of influential supporters among the English aristocracy, such as John of Gaunt, the movement was not allowed to survive. Though Wycliffe himself was left unmolested, his supporters, the Lollards, were eventually suppressed in England.[107]

Richard II of England's marriage to Anne of Bohemia established contacts between the two nations and brought Lollard ideas to this part of Europe.[108] The teachings of the Czech priest Jan Hus were based on those of John Wyclif, yet his followers, the Hussites, were to have a much greater political impact than the Lollards.[109] Hus gained a great following in Bohemia, and in 1414, he was requested to appear at the Council of Constance, to defend his cause.[110] When he was burned as a heretic in 1415, it caused a popular uprising in the Czech lands.[111] The subsequent Hussite Wars fell apart due to internal quarrels, and did not result in religious or national independence for the Czechs, but both the Catholic Church and the German element within the country were weakened.[112]

Martin Luther, a German monk, started the German Reformation by the posting of the 95 theses on the castle church of Wittenberg on October 31, 1517.[113] The immediate provocation behind the act was Pope Leo X’s renewing the indulgence for the building of the new St. Peter's Basilica in 1514.[114] Luther was challenged to recant his heresy at the Diet of Worms in 1521.[115] When he refused, he was placed under the ban of the Empire by Charles V.[116] Receiving the protection of Frederick the Wise, he was then able to translate the Bible into German.[117]

To many secular rulers, the Protestant reformation was a welcome opportunity to expand their wealth and influence.[118] The Catholic Church met the challenges of the reforming movements with what has been called the Catholic or Counter-Reformation.[119] Europe became split into a northern Protestant and a southern Catholic part, resulting in the Religious Wars of the 16th and 17th centuries.[120]

Trade and commerce

| Medieval Merchant Routes |

|---|

Hansa Venetian Genoese Venetian and Genoese (stippled) Overland and river routes |

The increasingly dominant position of the Ottoman Empire in the eastern Mediterranean presented an impediment to trade for the Christian nations of the west, who in turn started looking for alternatives.[121] Portuguese and Spanish explorers found new trade routes – south of Africa to India, and across the Atlantic Ocean to America.[122] As Genoese and Venetian merchants opened up direct sea routes with Flanders, the Champagne fairs lost much of their importance.[123]

At the same time, English wool export shifted from raw wool to processed cloth, resulting in losses for the cloth manufacturers of the Low Countries.[124] In the Baltic and North Sea, the Hanseatic League reached the peak of their power in the 14th century, but started going into decline in the fifteenth.[125]

In the late 13th and early 14th centuries, a process took place – primarily in Italy but partly also in the Empire – that historians have termed a 'commercial revolution'.[126] Among the innovations of the period were new forms of partnership and the issuing of insurance, both of which contributed to reducing the risk of commercial ventures; the bill of exchange and other forms of credit that circumvented the canonical laws for gentiles against usury, and eliminated the dangers of carrying bullion; and new forms of accounting, in particular double-entry bookkeeping, which allowed for better oversight and accuracy.[127]

With the financial expansion, trading rights became more jealously guarded by the commercial elite. Towns saw the growing power of guilds, while on a national level special companies would be granted monopolies on particular trades, like the English wool Staple.[128] The beneficiaries of these developments would accumulate immense wealth. Families like the Fuggers in Germany, the Medicis in Italy, the de la Poles in England, and individuals like Jacques Coeur in France would help finance the wars of kings, and achieve great political influence in the process.[129]

Though there is no doubt that the demographic crisis of the 14th century caused a dramatic fall in production and commerce in absolute terms, there has been a vigorous historical debate over whether the decline was greater than the fall in population.[130] While the older orthodoxy was that the artistic output of the Renaissance was a result of greater opulence, more recent studies have suggested that there might have been a so-called 'depression of the Renaissance'.[131] In spite of convincing arguments for the case, the statistical evidence is simply too incomplete that a definite conclusion can be made.[132]

Arts and sciences

In the 14th century, the predominant academic trend of scholasticism was challenged by the humanist movement. Though primarily an attempt to revitalise the classical languages, the movement also led to innovations within the fields of science, art and literature, helped on by impulses from Byzantine scholars who had to seek refuge in the west after the Fall of Constantinople in 1453.[133]

In science, classical authorities like Aristotle were challenged for the first time since antiquity. Within the arts, humanism took the form of the Renaissance. Though the 15th century Renaissance was a highly localised phenomenon – limited mostly to the city states of northern Italy – artistic developments were taking place also further north, particularly in the Netherlands.[13]

Philosophy, science and technology

The predominant school of thought in the 13th century was the Thomistic reconciliation of the teachings of Aristotle with Christian theology.[134] The Condemnation of 1277, enacted at the University of Paris, placed restrictions on ideas that could be interpreted as heretical; restrictions that had implication for Aristotelian thought.[135] An alternative was presented by William of Ockham, who insisted that the world of reason and the world of faith had to be kept apart. Ockham introduced the principle of parsimony – or Occam's razor – whereby a simple theory is preferred to a more complex one, and speculation on unobservable phenomena is avoided.[136]

This new approach liberated scientific speculation from the dogmatic restraints of Aristotelian science, and paved the way for new approaches. Particularly within the field of theories of motion great advances were made, when such scholars as Jean Buridan, Nicole Oresme and the Oxford Calculators challenged the work of Aristotle.[137] Buridan developed the theory of impetus as the cause of the motion of projectiles, which was an important step towards the modern concept of inertia.[138] The works of these scholars anticipated the heliocentric worldview of Nicolaus Copernicus.[139]

Certain technological inventions of the period – whether of Arab or Chinese origin, or unique European innovations – were to have great influence on political and social developments, in particular gunpowder, the printing press and the compass. The introduction of gunpowder to the field of battle affected not only military organisation, but helped advance the nation state. Gutenberg's movable type printing press made possible not only the Reformation, but also a dissemination of knowledge that would lead to a gradually more egalitarian society. The compass, along with other innovations such as the cross-staff, the mariner's astrolabe, and advances in shipbuilding, enabled the navigation of the World Oceans, and the early phases of colonialism.[140] Other inventions had a greater impact on everyday life, such as eyeglasses and the weight-driven clock.[141]

Visual arts and architecture

| Medieval art |

|---|

|

Giotto's three-dimensional and psychologically convincing characters were a precursor to the Renaissance. |

A precursor to Renaissance art can be seen already in the early 14th century works of Giotto. Giotto was the first painter since antiquity to attempt the representation of a three-dimensional reality, and to endow his characters with true human emotions.[142] The most important developments, however, came in 15th century Florence. The affluence of the merchant class allowed extensive patronage of the arts, and foremost among the patrons were the Medici.[143]

The period saw several important technical innovations, like the principle of linear perspective found in the work of Masaccio, and later described by Brunelleschi.[144] Greater realism was also achieved through the scientific study of anatomy, championed by artists like Donatello.[145] This can be seen particularly well in his sculptures, inspired by the study of classical models.[146] As the centre of the movement shifted to Rome, the period culminated in the High Renaissance masters da Vinci, Michelangelo and Raphael.[147]

The ideas of the Italian Renaissance were slow to cross the Alps into northern Europe, but important artistic innovations were made also in the Low Countries.[148] Though not – as previously believed – the inventor of oil painting, Jan van Eyck was a champion of the new medium, and used it to create works of great realism and minute detail.[149] The two cultures influenced each other and learned from each other, but painting in the Netherlands remained more focused on textures and surfaces than the idealised compositions of Italy.[150]

In northern European countries gothic architecture remained the norm, and the gothic cathedral was further elaborated.[151] In Italy, on the other hand, architecture took a different direction, also here inspired by classical ideals. The crowning work of the period was the Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, with Giotto's clock tower, Ghiberti's baptistery gates, and Brunelleschi's cathedral dome of unprecedented proportions.[152]

Literature

The most important development of late medieval literature was the ascendancy of the vernacular languages.[153] The vernacular had been in use in France and England since the 11th century, where the most popular genres had been the chanson de geste, troubadour lyrics and romantic epics, or the romance.[154] Though Italy was later in evolving a native literature in the vernacular language, it was here that the most important developments of the period were to come.[155]

Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy, written in the early 14th century, merged a medieval world view with classical ideals.[156] Another promoter of the Italian language was Boccaccio with his Decameron.[157] The application of the vernacular did not entail a rejection of Latin, and both Dante and Boccaccio wrote prolifically in Latin as well as Italian, as would Petrarch later (whose Canzoniere also promoted the vernacular and whose contents are considered the first modern lyric poems).[158] Together the three poets established the Tuscan dialect as the norm for the modern Italian language.[159]

The new literary style spread rapidly, and in France influenced such writers as Eustache Deschamps and Guillaume de Machaut.[160] In England Geoffrey Chaucer helped establish English as a literary language with his Canterbury Tales, which tales of everyday life were heavily influenced by Boccaccio.[161] The spread of vernacular literature eventually reached as far as Bohemia, and the Baltic, Slavic and Byzantine worlds.[162]

Music

Music was an important part of both secular and spiritual culture, and in the universities it made up part of the quadrivium of the liberal arts.[163] From the early 13th century, the dominant sacred musical form had been the motet; a composition with text in several parts.[164] From the 1330s and onwards, emerged the polyphonic style, which was a more complex fusion of independent voices.[165] Polyphony had been common in the secular music of the Provençal troubadours. Many of these had fallen victim to the 13th century Albigensian Crusade, but their influence reached the papal court at Avignon.[166]

The main representatives of the new style, often referred to as ars nova as opposed to the ars antiqua, were the composers Philippe de Vitry and Guillaume de Machaut.[167] In Italy, where the Provençal troubadours had also found refuge, the corresponding period goes under the name of trecento, and the leading composers were Giovanni da Cascia, Jacopo da Bologna and Francesco Landini.[168]

Theatre

In the British Isles, plays were produced in some 127 different towns during the Middle Ages. These vernacular Mystery plays were written in cycles of a large number of plays: York (48 plays), Chester (24), Wakefield (32) and Unknown (42). A larger number of plays survive from France and Germany in this period and some type of religious dramas were performed in nearly every European country in the Late Middle Ages. Many of these plays contained comedy, devils, villains and clowns.[169]

Morality plays emerged as a distinct dramatic form around 1400 and flourished until 1550. The most interesting morality play is The Castle of Perseverance which depicts mankind's progress from birth to death. However, the most famous morality play and perhaps best known medieval drama is Everyman. Everyman receives Death's summons, struggles to escape and finally resigns himself to necessity. Along the way, he is deserted by Kindred, Goods, and Fellowship - only Good Deeds goes with him to the grave.

At the end of the Late Middle Ages, professional actors began to appear in England and Europe. Richard III and Henry VII both maintained small companies of professional actors. Their plays were performed in the Great Hall of a nobleman's residence, often with a raised platform at one end for the audience and a "screen" at the other for the actors. Also important were Mummers' plays, performed during the Christmas season, and court masques. These masques were especially popular during the reign of Henry VIII who had a House of Revels built and an Office of Revels established in 1545.[170]

The end of medieval drama came about due to a number of factors, including the weakening power of the Catholic Church, the Protestant Reformation and the banning of religious plays in many countries. Elizabeth I forbid all religious plays in 1558 and the great cycle plays had been silenced by the 1580s. Similarly, religious plays were banned in the Netherlands in 1539, the Papal States in 1547 and in Paris in 1548. The abandonment of these plays destroyed the international theatre that had thereto existed and forced each country to develop its own form of drama. It also allowed dramatists to turn to secular subjects and the reviving interest in Greek and Roman theatre provided them with the perfect opportunity.[171]

After the Middle Ages

After the end of the late Middle Ages period, the Renaissance would spread unevenly over continental Europe from the southern European region. The intellectual transformation of the Renaissance is viewed as a bridge between the Middle Ages and the Modern era. Europeans would later begin an era of world discovery. Combined with the influx of classical ideas was the invention of printing which facilitated dissemination of the printed word and democratized learning. These two things would lead to the Protestant Reformation. Europeans also discovered new trading routes, as was the case with Columbus’s travel to the Americas in 1492, and Vasco da Gama’s circumnavigation of Africa and India in 1498. Their discoveries strengthened the economy and power of European nations.

The period 1300–1500 in Asia and North Africa

Islamic world

Mamluk Sultanate

At the time of the fall of the Ayyubids, the Mamluk Sultanate rose to ruled Egypt. The Mamluks, Arabs and Kipchak Turks, were purchased but were not ordinary slaves. Mamluks were considered to be “true lords,” with social status above freeborn Egyptian Muslims. Mamluk regiments constituted the backbone of the late Ayyubid military. Each sultan and high-ranking amir had his private corps. The Bahri mamluks defeated the Louis IX's crusaders at the Battle of Al Mansurah. The Sultan proceeded to place his own entourage and Mu`azzamis mamluks in authority to the detriment of Bahri interests. Shhortly thereafter, a group of Bahris assassinated the Sultan. Following the death of the Sultan, a decade of instability ensued as various factions competed for control. The Ottoman Sultan of the Ottoman Empire conquered Syria at the end of the Middle Ages after defeating the Mamlukes at the Battle of Marj Dabiq near Aleppo. The Ottoman's campaign against the Mamlukes continued and they conquered Egypt following the Battle of Ridanieh, bringing an end to the Mamluk Sultanate.

Ottomans and Europe

| Ottomans and Europe | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

In the end of the 15th century the Ottoman Empire advanced all over East Europe conquering eventually the Byzantine Empire and extending their control on the states of the Balkans. Hungary became eventually the last bastion of the Latin Christian world, and fought for the keeping its rule on his territories during two centuries. After the tragic death of the young King Vladislaus I of Hungary during the Battle of Varna in 1444 against the Ottomans, the Kingdom without monarch was placed in the hands of the count John Hunyadi, who became Hungary's regent-governor (1446–1453). Hunyadi was considered by the pope as one of the most relevant military figures of the 15th century (Pope Pius II awarded him with the title of Athleta Christi or Champion of Christ), because he was the only hope of keeping a resistance against the Ottomans in Central and West Europe.

Hunyadi succeeded during the Siege of Belgrade in 1456 against the Ottomans, which meant the biggest victory against that empire in decades. This battle became a real Crusade against the Muslims, as the peasants were motivated by the Franciscan monk Saint John of Capistrano, which came from Italy predicating the Holy War. The effect that it created in that time was one of the few main factors that helped achieving the victory. However the premature death of the Hungarian Lord left defenseless and in chaos that area of Europe.[172] As an absolutely unusual event for the Middle Ages, Hunyadi's son, Matthias, was elected as King for Hungary by the nobility. For the first time, a member of an aristocratic family (and not from a royal family) was crowned.[173]

The King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary (1458–1490) was one of the most prominent figures of this Age, as he directed campaigns to the west conquering Bohemia answering to the Pope's claim for help against the Hussite Protestants, and also for solving the political hostilities with the German emperor Frederick III of Habsburg he invaded his west domains. Matthew organized the Black Army, composed of mercenary soldiers that is considered until the date as the biggest army of its time. Using this powerful tool, the Hungarian king led wars against the Turkish armies and stopped the Ottomans during his reign. Though the Ottoman Empire grew in strength and, with end of the Black Army, Central Europe was defenseless after the death of Matthew. At the Battle of Mohács, the forces of the Ottoman Empire annihilated the Hungarian army, and in trying to escape Louis II of Hungary drowned in the Csele Creek. The leader of the Hungarian army, Pál Tomori, also died in the battle. This episode is considered to be one of the final ones of the Medieval Times.[174]

Far East

Chinese restoration

| Yuan coinage |

|---|

|

The Mongol Great Yuan Empire, founded by Kublai Khan, existed between the high and late Middle Ages. A division of the Mongol Empire and a imperial dynasty of China, the Yuan followed the Song Dynasty and preceded the Ming Dynasty. During his rule, Kublai Khan claimed the title of Great Khan, supreme Khan over the other Mongol khanates. This claim was only truly recognized by the Il-Khanids, who were nevertheless essentially self-governing. Although later emperors of the Yuan Dynasty were recognized by the three virtually independent western khanates as their nominal suzerains, they each continued their own separate developments.

The Empire of the Great Ming rule began in China during the mid-late Middle Ages, following the collapse of the Yuan Dynasty. The Ming was the last dynasty in China ruled by ethnic Han Chinese. Ming rule saw the construction of a vast navy and army. Although private maritime trade and official tribute missions from China had taken place in previous dynasties, the tributary fleet under the Muslim eunuch admiral Zheng He surpassed all others in size.

| Forbidden City |

|---|

|

In the Ming Dynasty, there were enormous construction projects, including the restoration of the Grand Canal and the Great Wall and the establishment of the Forbidden City in Beijing. Society was fashioned to be self-sufficient rural communities in a rigid, immobile system that would have no need to engage with the commercial life and trade of urban centers. Rebuilding of China's agricultural base and strengthening of communication routes through the militarized courier system had the unintended effect of creating a vast agricultural surplus that could be sold at burgeoning markets located along courier routes.

Rural culture and commerce became influenced by urban trends. The upper echelons of society embodied in the scholarly gentry class were also affected by this new consumption-based culture. In a departure from tradition, merchant families began to produce examination candidates to become scholar-officials and adopted cultural traits and practices typical of the gentry. Parallel to this trend involving social class and commercial consumption were changes in social and political philosophy, bureaucracy and governmental institutions, and even arts and literature.

Japanese restoration

The Kenmu restoration was a three year period of Japanese history between the Kamakura period and the Muromachi period. The political events included the restoration effort, but made with many and serious political errors, to bring the Imperial House and the nobility it represented back into power, thus restoring a civilian government after almost a century and a half of military rule. The attempted restoration ultimately failed and was replaced by the Ashikaga shogunate. This was to be the last time the Emperor had any power until the Meiji restoration in the modern era.

Beginning around the mid-late Middle Ages, the Muromachi period marks the governance of the Ashikaga shogunate. The first Muromachi shogun was established by Ashikaga Takauji, two years after the brief Kemmu restoration of imperial rule was brought to a close. The period ended with the last shogun, Ashikaga Yoshiaki, driven out of the capital in Kyoto by Oda Nobunaga. The early Muromachi period, or the Northern and Southern Court period, experienced continued resistance of the supporters of the Kemmu restoration. The end of the Muromachi period, or the Sengoku period, was a time of warring states. The Muromachi period has the two cultural phases, the medieval Kitayama and modern Higashiyama periods.

Timeline

It has been suggested that this section be split out into another article titled Timeline of the Late Middle Ages. (Discuss) (July 2011) |

- Dates are approximate, consult particular article for details

- Middle Ages Themes Other themes

- 14th century

|

1307 - The Knights Templar destroyed |

1378 - The Avignon Papacy ends |

- 15th century

|

1409 - Venetian's Dalmatia |

1461 - The Empire of Trebizond falls |

|

|

|

|

See also

- List of basic medieval history topics

- Timeline of the Middle Ages

- Church and state in medieval Europe

- History of the Jews in the Middle Ages

- Thirteen forty-five – In-depth treatment of the year

References

Constructs such as ibid., loc. cit. and idem are discouraged by Wikipedia's style guide for footnotes, as they are easily broken. Please improve this article by replacing them with named references (quick guide), or an abbreviated title. (October 2011) |

Sources

General:

- The New Cambridge Medieval History, vol. 6: c. 1300 - c. 1415, (2000). Michael Jones (ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-36290-3.

- The New Cambridge Medieval History, vol. 7: c. 1415 - c. 1500, (1998). Christopher Allmand (ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-38296-3.

- Brady, Thomas A., Jr., Heiko A. Oberman, James D. Tracy (eds.) (1994). Handbook of European History, 1400–1600: Late Middle Ages, Renaissance and Reformation. Leiden, New York: E.J. Brill. ISBN 9004097627.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Cantor, Norman (1994). The Civilization of the Middle Ages. New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 0060170336.

- Hay, Denys (1988). Europe in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries (2nd ed.). London: Longman. ISBN 0582491797.

- Hollister, C. Warren (2005). Medieval Europe: A Short History (10th ed.). McGraw-Hill Higher Education. ISBN 0072955155.

- Holmes, George (ed.) (2001). The Oxford History of Medieval Europe (New ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192801333.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Keen, Maurice (1991). The Penguin History of Medieval Europe (New ed.). London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0140136304.

- Le Goff, Jacques (2005). The Birth of Europe: 400-1500. WileyBlackwell. ISBN 0631228888.

- Waley, Daniel; Denley, Peter (2001). Later Medieval Europe: 1250-1520 (3rd ed.). London: Longman. ISBN 0582258316.

Specific regions:

- Abulafia, David (1997). The Western Mediterranean Kingdoms: The Struggle for Dominion, 1200-1500. London: Longman. ISBN 0582078202.

- Duby, Georges (1993). France in the Middle Ages, 987-1460: From Hugh Capet to Joan of Arc (New ed.). WileyBlackwell. ISBN 0631189459.

- Fine, John V.A. (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest (Reprint ed.). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472082604.

- Jacob, E.F. (1961). The Fifteenth Century: 1399–1485. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-821714-5.

- McKisack, May (1959). The Fourteenth Century: 1307–1399. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-821712-9.

- Mango, Cyril (ed.) (2002). The Oxford History of Byzantium. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198140983.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Martin, Janet (2007). Medieval Russia, 980–1584 (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521859166.

- Najemy, John M. (ed.) (2004). Italy in the Age of the Renaissance: 1300-1550 (New ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198700407.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Reilly, Bernard F. (1993). The Medieval Spains. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521397413.

- Wandycz, Piotr (2001). The Price of Freedom: A History of East Central Europe from the Middle Ages to the Present (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0415254914.

Society:

- Chazan, Robert (2006). The Jews of Medieval Western Christendom: 1000-1500. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521616646.

- Herlihy, David (1985). Medieval Households. Cambridge, Massachusetts; London: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674563751.

- Herlihy, David (1968). Medieval Culture and Society. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0881337471.

- Jordan, William Chester (1996). The Great Famine: Northern Europe in the Early Fourteenth Century. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691011346.

- Klapisch-Zuber, Christiane (1994). A history of women in the West (New ed.). Cambridge, Mass.; London: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674403681.

The Black Death:

- Benedictow, Ole J. (2004). The Black Death 1346-1353: The Complete History. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 0851159435.

- Herlihy, David (1997). The Black Death and the transformation of the West. Cambridge, Mass.; London: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0750932023.

- Horrox, Rosemary (1994). The Black Death. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0719034973.

- Ziegler, Philip (2003). The Black Death (New ed.). Sutton: Sutton Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0750932023.

Warfare:

- Allmand, Christopher (1988). The Hundred Years War: England and France at War c.1300-c.1450. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521319234.

- Contamine, Philippe (1984). War in the Middle Ages. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0631131426.

- Curry, Anne (1993). The Hundred Years War. Basingstoke: Macmillan. ISBN 0333531752.

- Keen, Maurice (1984). Chivalry. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300031505.

- Verbruggen, J. F. (1997). The Art of Warfare in Western Europe during the Middle Ages: From the Eighth Century to 1340 (2nd ed.). Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 0851156304.

Economy:

- Cipolla, Carlo M. (1993). Before the Industrial Revolution: European Society and Economy 1000–1700 (3rd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0415090059.

- Cipolla, Carlo M. (ed.) (1993). The Fontana Economic History of Europe, Volume 1: The Middle Ages (2nd ed.). New York: Fontana Books. ISBN 0855271590.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Postan, M.M. (2002). Mediaeval Trade and Finance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521522021.

- Pounds, N.J.P. (1994). An Economic History of Medieval Europe (2nd ed.). London and New York: Longman. ISBN 0582215994.

Religion:

- Kenny, Anthony (1985). Wyclif. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192876473.

- MacCulloch, Diarmaid (2005). The Reformation. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-303538-X.

- Ozment, Steven E. (1980). The Age of Reform, 1250-1550: An Intellectual and Religious History of Late Medieval and Reformation Europe. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300024770.

- Smith, John H. (1970). The Great Schism, 1378. London: Hamilton. ISBN 0241015200.

- Southern, R.W. (1970). Western society and the Church in the Middle Ages. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. ISBN 0140205039.

Arts and science:

- Brotton, Jerry (2006). The Renaissance: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192801635.

- Burke, Peter (1998). The European Renaissance: Centres and Peripheries (2nd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0631198458.

- Curtius, Ernest Robert (1991). European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages (New ed.). New York: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691018995.

- Grant, Edward (1996). The Foundations of Modern Science in the Middle Ages: Their Religious, Institutional, and Intellectual Contexts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521567629.

- Snyder, James (2004). Northern Renaissance Art: Painting, Sculpture, the Graphic Arts from 1350 to 1575 (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 0131895648.

- Welch, Evelyn (2000). Art in Renaissance Italy, 1350-1500 (reprint ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-284279-X.

- Wilson, David Fenwick (1990). Music of the Middle Ages. New York: Schirmer Books. ISBN 0-02-872951-X.

Citations

- ^ Austin Alchon, Suzanne (2003). A pest in the land: new world epidemics in a global perspective. University of New Mexico Press. p. 21. ISBN 0826328717.

- ^ Cantor, p. 480.

- ^ Cantor, p. 594.

- ^ Leonardo Bruni, James Hankins, History of the Florentine people, Volume 1, Books 1–4, (2001), p. xvii.

- ^ Brady et al., p. xiv; Cantor, p. 529.

- ^ Burckhardt, Jacob (1860). The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy. p. 121. ISBN 0060904607.

- ^ Haskins, Charles Homer (1927). The Renaissance of the Twelfth Century. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0198219342.

- ^ "Les periodes de l'historie du capitalism", Academie Royale de Belgique. Bulletin de la Classe des Lettres, 1914.

- ^ Huizinga, Johan (1924). The Waning of the Middle Ages: A Study of the Forms of Life, Thought and Art in France and the Netherlands in the XIVth and XVth Centuries. London: E. Arnold. ISBN 0312855400.

- ^ a b Allmand, p. 299; Cantor, p. 530.

- ^ Le Goff, p. 154. See e.g. Najemy, John M. (2004). Italy in the Age of the Renaissance: 1300–1550. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198700407.

- ^ a b c Brady et al., p. xvii.

- ^ a b For references, see below.

- ^ Allmand (1998), p. 3; Holmes, p. 294; Koenigsberger, pp. 299–300.

- ^ Brady et al., p. xvii; Jones, p. 21.

- ^ Allmand (1998), p. 29; Cantor, p. 514; Koenigsberger, pp. 300–3.

- ^ Brady et al., p. xvii; Holmes, p. 276; Ozment, p. 4.

- ^ Hollister, p. 366; Jones, p. 722.

- ^ Allmand (1998), p. 703

- ^ Bagge, Sverre (1989). Norge i dansketiden: 1380–1814 (2nd ed.). Oslo: Cappelen. ISBN 9788202123697.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Allmand (1998), p. 673.

- ^ Allmand (1998), p. 193.

- ^ Alan Cutler (1997-08-13). "The Little Ice Age: When global cooling gripped the world". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

- ^ Jones, pp. 348–9.

- ^ Jones, pp. 350–1; Koenigsberger, p. 232; McKisack, p. 40.

- ^ Jones, p. 351.

- ^ Allmand (1998), p. 458; Koenigsberger, p. 309.

- ^ Allmand (1998), p. 458; Nicholas, pp. 32–3.

- ^ Hollister, p. 353; Jones, pp. 488–92.

- ^ McKisack, pp. 228–9.

- ^ Hollister, p. 355; Holmes, pp. 288-9; Koenigsberger, p. 304.

- ^ Duby, p. 288-93; Holmes, p. 300.

- ^ Allmand (1998), pp. 450-5; Jones, pp. 528-9.

- ^ Allmand (1998), p. 455; Hollister, p. 355; Koenigsberger, p. 304.

- ^ Allmand (1998), p. 455; Hollister, p. 363; Koenigsberger, pp. 306-7.

- ^ Holmes, p. 311–2; Wandycz, p. 40

- ^ Hollister, p. 362; Holmes, p. 280.

- ^ Cantor, p. 507; Hollister, p. 362.

- ^ Allmand (1998), pp. 152–153; Cantor, p. 508; Koenigsberger, p. 345.

- ^ Wandycz, p. 38.

- ^ Wandycz, p. 40.

- ^ Jones, p. 737.

- ^ Koenigsberger, p. 318; Wandycz, p. 41.

- ^ Jones, p. 7.

- ^ Martin, pp. 100–1.

- ^ Koenigsberger, p. 322; Jones, p. 793; Martin, pp. 236–7.

- ^ Martin, p. 239.

- ^ Allmand (1998), p. 754; Koenigsberger, p. 323.

- ^ Allmand, p. 769; Hollister, p. 368.

- ^ Hollister, p. 49.

- ^ Allmand (1998), pp. 771–4; Mango, p. 248.

- ^ Hollister, p. 99; Koenigsberger, p. 340.

- ^ Jones, pp. 796–7.

- ^ Jones, p. 875.

- ^ a b Hollister, p. 360; Koenigsberger, p. 339.

- ^ Hollister, p. 338.

- ^ Allmand (1998), p. 586; Hollister, p. 339; Holmes, p. 260.

- ^ Allmand, pp. 150, 155; Cantor, p. 544; Hollister, p. 326.

- ^ Allmand (1998), p. 547; Hollister, p. 363; Holmes, p. 258.

- ^ Cantor, p. 511; Hollister, p. 264; Koenigsberger, p. 255.

- ^ Allmand (1998), p. 577.

- ^ Hollister, p. 356; Koenigsberger, p. 314; Reilly, p. 209.

- ^ Allmand (1998), p. 162; Hollister, p. 99; Holmes, p. 265.

- ^ Allmand (1998), p. 192; Cantor, 513.

- ^ Cantor, 513; Holmes, pp. 266–7.

- ^ Grove, Jean M. (2003). The Little Ice Age. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415014492.

- ^ Jones, p. 88.

- ^ Harvey, Barbara F. (1991). "Introduction: The 'Crisis' of the Early Fourteenth Century". In Campbell, B.M.S. (ed.). Before the Black Death: Studies in The 'Crisis' of the Early Fourteenth Century. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 1–24. ISBN 0-7190-3208-3.

- ^ Jones, pp. 136–8;Cantor, p. 482.

- ^ Herlihy (1997), p. 17; Jones, p. 9.

- ^ Hollister, p. 347.

- ^ Duby, p. 270; Koenigsberger, p. 284; McKisack, p. 334.

- ^ Koenigsberger, p. 285.

- ^ Cantor, p. 484; Hollister, p. 332; Holmes, p. 303.

- ^ Cantor, p. 564; Hollister, pp. 332–3; Koenigsberger, p. 285.

- ^ Hollister, pp. 332–3; Jones, p. 15.

- ^ Chazan, p. 194.

- ^ Hollister, p. 330; Holmes, p. 255.

- ^ Brady et al., pp. 266–7; Chazan, pp. 166, 232; Koenigsberger, p. 251.

- ^ a b Klapisch-Zuber, p. 268.

- ^ Hollister, p. 323; Holmes, p. 304.

- ^ Jones, p. 164; Koenigsberger, p. 343.

- ^ a b Allmand (1998), p. 125

- ^ Jones, p. 350; McKisack, p. 39; Verbruggen, p. 111.

- ^ Allmand (1988), p. 59; Cantor, p. 467.

- ^ McKisack, p. 240, Verbruggen, pp. 171–2

- ^ Contamine, pp. 139–40; Jones, pp. 11–2.

- ^ Contamine, pp. 198–200.

- ^ Allmand (1998), p. 169; Contamine, pp. 200–7.

- ^ Cantor, p. 515.

- ^ Contamine, pp. 150–65; Holmes, p. 261; McKisack, p. 234.

- ^ Contamine, pp. 124, 135.

- ^ Contamine, pp. 165–72; Holmes, p. 300.

- ^ Cantor, p. 349; Holmes, pp. 319–20.

- ^ Hollister, p. 336.

- ^ http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03691a.htm

- ^ Cantor, p. 537; Jones, p. 209; McKisack, p. 251.

- ^ Cantor, p. 496.

- ^ Cantor, p. 497; Hollister, p. 338; Holmes, p. 309.

- ^ Hollister, p. 338; Koenigsberger, p. 326; Ozment, p. 158.

- ^ Cantor, p. 498; Ozment, p. 164.

- ^ Koenigsberger, pp. 327–8; MacCulloch, p. 34.

- ^ Hollister, p. 339; Holmes, p. 260; Koenigsberger, pp. 327–8.

- ^ A famous account of the nature of, and suppression of a heretic movement, is Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie's Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie. (1978). Montaillou: Cathars and Catholics in a French Village, 1294–1324. London: Scolar Press. ISBN 0859674037.

- ^ MacCulloch, p. 34–5.

- ^ Allmand (1998), p. 15; Cantor, pp. 499–500; Koenigsberger, p. 331.

- ^ Allmand (1998), pp. 15–6; MacCulloch, p. 35.

- ^ Holmes, p. 312; MacCulloch, pp. 35–6; Ozment, p. 165.

- ^ Allmand (1998), p. 16; Cantor, p. 500.

- ^ Allmand (1998), p. 377; Koenigsberger, p. 332.

- ^ Koenigsberger, p. 332; MacCulloch, p. 36.

- ^ Allmand (1998), p. 353; Hollister, p. 344; Koenigsberger, p. 332–3.

- ^ MacCulloch, p. 115.

- ^ MacCulloch, pp. 70, 117.

- ^ MacCulloch, p. 127; Ozment, p. 245.

- ^ MacCulloch, p. 128.

- ^ Ozment, p. 246.

- ^ Allmand (1998), pp. 16–7; Cantor, pp. 500–1.

- ^ MacCulloch, p. 107; Ozment, p. 397.

- ^ MacCulloch, p. 266; Ozment, pp. 259–60.

- ^ Allmand (1998), pp. 159–60; Pounds, pp. 467–8.

- ^ Hollister, pp. 334–5.

- ^ Cipolla (1976), p. 275; Koenigsberger, p. 295; Pounds, p. 361.

- ^ Cipolla (1976), p. 283; Koenigsberger, p. 297; Pounds, pp. 378–81.

- ^ Cipolla (1976), p. 275; Cipolla (1994), p. 203, 234; Pounds, pp. 387–8.

- ^ Koenigsberger, p. 226; Pounds, p. 407.

- ^ Cipolla (1976), pp. 318–29; Cipolla (1994), pp. 160–4; Holmes, p. 235; Jones, pp. 176–81; Koenigsberger, p. 226; Pounds, pp. 407–27.

- ^ Jones, p. 121; Pearl, pp. 299–300; Koenigsberger, pp. 286, 291.

- ^ Allmand (1998), pp. 150–3; Holmes, p. 304; Koenigsberger, p. 299; McKisack, p. 160.

- ^ Pounds, p. 483.

- ^ Cipolla, C.M. (1964). "Economic depression of the Renaissance?". Economic History Review. xvi: 519–24.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ Pounds, pp. 484–5.

- ^ Allmand (1998), pp. 243–54; Cantor, p. 594; Nicholas, p. 156.

- ^ Jones, p. 42; Koenigsberger, p. 242.

- ^ Hans Thijssen (2003). "Condemnation of 1277". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2008-04-21.

- ^ Grant, p. 142; Nicholas, p. 134.

- ^ Grant, pp. 100–3, 149, 164–5.

- ^ Grant, pp. 95–7.

- ^ Grant, pp. 112–3.

- ^ Jones, pp. 11–2; Koenigsberger, pp. 297–8; Nicholas, p. 165.

- ^ Grant, p. 160; Koenigsberger, p. 297.

- ^ Cantor, p. 433; Koenigsberger, p. 363.

- ^ Allmand (1998), p. 155; Brotton, p. 27.

- ^ Burke, p. 24; Koenigsberger, p. 363; Nicholas, p. 161.

- ^ Allmand (1998), p. 253; Cantor, p. 556.

- ^ Cantor, p. 554; Nichols, pp. 159–60.

- ^ Brotton, p. 67; Burke, p. 69.

- ^ Allmand (1998), p. 269; Koenigsberger, p. 376.

- ^ Allmand (1998), p. 302; Cantor, p. 539.

- ^ Burke, p. 250; Nicholas, p. 161.

- ^ Allmand (1998), pp. 300–1, Hollister, p. 375.

- ^ Allmand (1998), p. 305; Cantor, p. 371.

- ^ Jones, p. 8.

- ^ Cantor, p. 346.

- ^ Curtius, p. 387; Koenigsberger, p. 368.

- ^ Cantor, p. 546; Curtius, pp. 351, 378.

- ^ Curtius, p. 396; Koenigsberger, p. 368; Jones, p. 258.

- ^ Curtius, p. 26; Jones, p. 258; Koenigsberger, p. 368.

- ^ Koenigsberger, p. 369.

- ^ Jones, p. 264.

- ^ Curtius, p. 35; Jones. p. 264.

- ^ Jones, p. 9.

- ^ Allmand, p. 319; Grant, p. 14; Koenigsberger, p. 382.

- ^ Allmand, p. 322; Wilson, p. 229.

- ^ Wilson, pp. 229, 289–90, 327.

- ^ Koenigsberger, p. 381; Wilson, p. 329.

- ^ Koenigsberger, p. 383; Wilson, p. 329.

- ^ Wilson, pp. 357–8, 361–2.

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 86)

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 101-103)

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Draskóczy, István (2000). A tizenötödik század története. Pannonica Kiadó. Budapest: Hungary.

- ^ Engel Pál, Kristó Gyula, Kubinyi András. (2005) Magyarország Története 1301- 1526. Budapest, Hungary: Osiris Kiadó.

- ^ Fügedi, Erik. (2004). Uram Királyom. Fekete Sas Kiadó Budapest:Hungary.