Roman Empire

- The Roman Empire should not be mistaken for the Holy Roman Empire (843–1806).

The Roman Empire is the term conventionally used to describe the Roman state in the centuries following its reorganization under the leadership of Caesar Augustus. Although Rome possessed a collection of tribute-states for centuries before the autocracy of Augustus, the pre-Augustan state is conventionally described as the Roman Republic. The difference between the Roman Empire and the Roman Republic lies primarily in the governing bodies and their relationship to each other.

For many years, historians made a distinction between the Principate, the period from Augustus until the Crisis of the Third Century, and the Dominate, the period from Diocletian until the end of the Empire in the West. According to this theory, during the Principate, from the Latin word princeps, meaning "the first," the only title Augustus would permit himself, the realities of dictatorship were cleverly hidden behind Republican forms, while during the Dominate, from the word dominus, meaning "Master", imperial power showed its naked face, with golden crowns and ornate imperial ritual. We now know that the situation was far more nuanced: certain historical forms continued until the Byzantine period, more than one thousand years after they were created, and displays of imperial majesty were common from the earliest days of the Empire.

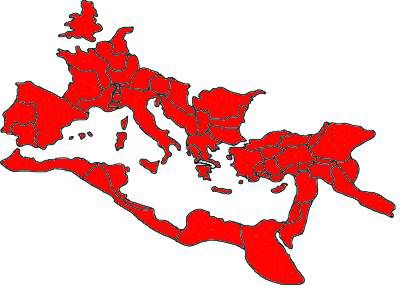

Over the course of its history, the Roman Empire controlled all of the Hellenized states that bordered the Mediterranean sea, as well as the Celtic regions of Western Europe. The administration of the Roman Empire eventually evolved into separate Eastern and Western halves, more or less following this cultural division. By the time that Odoacer took power of the West in 476, the Western half was clearly evolving in new directions, with the Church absorbing much of the administrative and charitable roles previously filled by the secular government. The Eastern half of the Empire, centered around Constantinople, the city of Constantine the Great, remained the heartland of the Roman state until 1453, when the Byzantine Empire fell to the Ottoman Turks.

The Roman Empire's influence on government, law, and monumental architecture, as well as many other aspects of Western life remains inescapable. Roman titles of power were adopted by successor states and other entities with imperial pretensions, including the Frankish kingdom, the Holy Roman Empire, the Russian/Kiev dynasties (see czars), and the German Empire (see Kaiser). See also: Roman culture

The Age of Augustus

Political Developments

As a matter of convenience, the Roman Empire is held to have begun with the constitutional settlement following the Battle of Actium in 31 BC. In fact, the Republican institutions at Rome had been destroyed over the preceding century and Rome had been effectively under one-man rule since the time of Sulla.

The reign of Augustus marks an important turning point, though. By the time of Actium, there was no one left alive who could recall functional Republican institutions or a time when there was no civil war in Rome. Forty-five years later, at Augustus's death, there would have been few living who could recall a time before Augustus himself. The average Roman had a life expectancy of only forty years. The long reign of Augustus allowed a generation to live and die knowing no other form of rule, or indeed no other ruler. This was critically important to creating a mindset that would allow hereditary monarchy to exist in a Rome that had killed Julius Caesar for his regal pretensions. Whether or not the people of Rome welcomed one-man rule, in the Age of Augustus, it was all they knew, and so it would remain for many centuries.

Augustus's reign was notable for several long-lasting achievements that would define the Empire:

- The creation of a hereditary office which we refer to as Emperor of Rome.

- The fixing of the payscale and duration of Roman military service marked the final step in the evolution of the Roman Army from a citizen army to a professional one.

- The creation of the Praetorian Guard, which would make and unmake emperors for centuries.

- Expansion to the natural borders of the Empire. The borders reached upon Augustus's death remained the limits of Empire, with minimal exceptions, for the next four hundred years.

- The creation of a civil service outside of the Senatorial structure, creating a continuous weakening of Senatorial authority.

- The lex Julia of 18 BC and the lex Papia Poppaea of AD 9, which rewarded childbearing and penalized celibacy.

- The promulgation of the cult of the Deified Julius Caesar throughout the Empire, and the encouragement of a quasi-godlike status for himself in his own lifetime in the Hellenist East. This tradition lasted until the time of Constantine, who was made both a Roman god and "the Thirteenth Apostle" upon his death.

Cultural Developments

The Augustan period saw a tremendous outpouring of cultural achievement in the areas of poetry, history, sculpture and architecture.

Sources

The Age of Augustus is, paradoxically, far more poorly documented than the Late Republican period that preceded it. While Livy wrote his magisterial history during Augustus's reign and his work covered all of Roman history through 9 BC, only epitomes survive of his coverage of the Late Republican and Augustan periods. Our important primary sources for this period include:

- the Res Gestae Divi Augusti, Augustus's highly partisan autobiography,

- the Historiae Romanae by Velleius Paterculus, a disorganized work which remains the best annal of the Augustan period, and

- the Controversiae and Suasoriae of Seneca the Elder.

Though primary accounts of this period are few, works of poetry, legislation and engineering from this period provide important insights into Roman life. Archeology, including maritime archeology, aerial surveys, epigraphic inscriptions on buildings, and Augustan coinage, has also provided valuable evidence about economic, social and military conditions.

Secondary sources on the Augustan Age include Tacitus, Dio Cassius, Plutarch and Suetonius. Josephus's Jewish Antiquities is the important source for Judea in this period, which became a province during Augustus's reign.

The heirs of Augustus: the Julio-Claudians

Augustus's strategy of intermarriage between the Julii and Claudii resulted in a combination of family and political relationships known as the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

Tiberius

The early years of Tiberius' reign were peaceful and relatively benign. Tiberius secured the power of Rome and enriched the treasury. However, Tiberius's reign soon became characterized by paranoia and slander. In 19, he was blamed for the death of his nephew, the popular Germanicus. In 23, his own son Drusus died. More and more, Tiberius retreated into himself. He began a series of treason trials and executions. He left power in the hands of the commander of the guard, Aelius Sejanus. Tiberius himself retired to live at his villa on the island of Capri in 26, leaving Sejanus in charge. Sejanus carried on the persecutions with relish. He also began to consolidate his own power; in 31, he was named co-consul with Tiberius and married Livilla, the emperor's niece. At this point, he was hoist by his own petard; the Emperor's paranoia, which he had so ably exploited for his own gain, was turned against him. Sejanus was put to death, along with many of his cronies, the same year. The persecutions continued apace until Tiberius's death in 37.

Caligula

At the time of Tiberius's death, most of the people who might have succeeded him had been brutally murdered. The logical successor (and Tiberius's own choice) was his grandnephew, Germanicus's son Gaius (better known as Caligula). Caligula started out well, by putting an end to the persecutions and burning his uncle's records. Unfortunately, he quickly lapsed into illness. The Caligula that emerged in late 37 may have suffered from epilepsy, and was more probably insane. He ordered his soldiers to invade Britain, but changed his mind at the last minute and had them pick sea shells on the northern end of France instead. It is believed he carried on incestuous relations with his sisters. He had ordered a statue of himself to be erected in the Temple at Jerusalem, which would have undoubtedly led to revolt had he not been dissuaded. In 41, Caligula was assassinated by the commander of the guard Cassius Chaerea. The only member left of the imperial family to take charge was another nephew of Tiberius's, Tiberius Claudius Drusus Nero Germanicus, better known as the emperor Claudius.

Claudius

Claudius had long been considered a weakling and a fool by the rest of his family. He was, however, neither paranoid like his uncle Tiberius, nor insane like his nephew Caligula, and was therefore able to administrate with reasonable ability. He improved the bureaucracy and streamlined the citizenship and senatorial rolls. He also proceeded with the conquest and colonization of Britain (in 43), and incorporated more Eastern provinces into the empire. In Italy, he constructed a winter port at Ostia, thereby providing a place for grain from other parts of the Empire to be brought in inclement weather.

On the home front, Claudius was less successful. His wife Messalina cuckolded him; when he found out, he had her executed and married his niece, Agrippina the younger. She, along with several of his freedmen, held an inordinate amount of power over him, and very probably killed him in 54. Claudius was deified later that year. The death of Claudius paved the way for Agrippina's own son, the 16-year-old Lucius Domitus, or, as he was known by this time, Nero.

Nero

Initially, Nero left the rule of Rome to his mother and his tutors, particularly Lucius Annaeus Seneca. However, as he grew older, his desire for power increased; he had his mother and tutors executed. During Nero's reign, there were a series of riots and rebellions throughout the Empire: in Britain, Armenia, Parthia, and Judaea. Nero's inability to manage the rebellions and his basic incompetence became evident quickly and in 68, even the Imperial guard renounced him. Nero committed suicide, and the year 69 (known as the Year of the Four Emperors) was a year of civil war, with the emperors Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and Vespasian ruling in quick succession. By the end of the year, Vespasian was able to solidify his power as emperor of Rome.

The Flavians

Vespasian

Vespasian was a remarkably successful Roman general who had been given rule over much of the eastern part of the Roman Empire. He had supported the imperial claims of Galba; however, on his death, Vespasian became a major contender for the throne. After the suicide of Otho, Vespasian was able to hijack Rome's winter grain supply, placing him in a good position to defeat his remaining rival, Vitellius. On December 20, 69, some of Vespasian's partisans were able to occupy Rome. Vitellius was murdered by his own troops, and the next day, Vespasian was confirmed as Emperor by the Senate.

Vespasian was quite the autocrat, and gave much less credence to the Senate than his Julio-Claudian predecessors. This was typified by his dating his accession to power from July 1, when his troops proclaimed him emperor, instead of December 21, when the Senate confirmed his appointment. He would, in later years, expel dissident senators.

Vespasian was able to liberate Rome from the financial burdens placed upon it by Nero's excesses and the civil wars. By increasing tax rates dramatically (sometimes as much as doubling them) he was able to build up a surplus in the treasury and embark on public works projects. It was he who first commissioned the Roman Colosseum; he also built a forum whose centerpiece was a temple to Peace.

Vespasian was also an effective emperor for the provinces. His generals quelled rebellions in Syria and Germany. In fact, in Germany he was able to expand the frontiers of the empire, and a great deal more of Britain was brought under Roman rule. He also extended Roman citizenship to the inhabitants of Spain.

Another example of his monarchical tendencies was his insistence that his sons Titus and Domitian would succeed him; the imperial power was not seen as hereditary at this point. Titus, who had some military successes early in Vespasian's reign, was seen as the heir presumptive to the throne; Domitian was seen as somewhat less disciplined and responsible. Titus joined his father in the offices of censor and consul and helped him reorganize the senatorial rolls. Upon Vespasian's death in 79, Titus was immediately confirmed as Emperor.

Titus

Titus' short reign was marked by disaster: in 79, Vesuvius erupted in Pompeii, and in 80, a fire decimated much of Rome. His generosity in rebuilding after these tragedies made him very popular. Titus was very proud of his work on the vast amphitheater begun by his father. He held the opening ceremonies in the still unfinished edifice during the year 80, celebrating with a lavish show that featured 100 gladiators and lasted 100 days. However, it was during Domitian's reign that the Colosseum was completed. Titus died in 81, at the age of 41; it was rumored that his brother Domitian murdered him in order to become his successor.

Domitian

Domitian did not live up to the good name left for the family by his father and elder brother. While his offenses may have been exaggerated by hostile later generations, it is clear that he did not like to share power. It had become accepted by Domitian's time that the emperor would simultaneously hold many of the magistracies established during Republican times (for instance the censorship and the tribunate), but it was still customary for other politicians to have those powers as well. Domitian wanted to claim authority for himself alone, causing him to alienate the Senate as well as the people.

The Antonines: the "five good emperors", 96 - 193 CE

The next century came to be known as the period of the "Five Good Emperors", in which the successions were peaceful though not dynastic, and the Empire was prosperous. The emperors were Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, and Marcus Aurelius.

Under Trajan, the Empire's borders briefly achieved their maximum extension with provinces created in Mesopotamia.

Commodus

Th period of the "five good emperors" was brought to an end by the reign of Commodus from 180 to 192. Commodus was the son of Marcus Aurelius. He was co-emperor with his father from 177. When he became sole emperor upon the death of his father in 180, it was at first seen as a hopeful sign by the people of the Roman Empire. Nevertheless, as generous and magnanimous as his father was, Commodus turned out to be just the opposite.

Commodus is often thought to have been insane, and he was certainly given to excess. He began his reign by making an unfavorable peace treaty with the Marcomanni, who had been at war with Marcus Aurelius. Commodus also had a passion for gladiatoral combat, which he took so far as to take to the arena himself, dressed as a gladiator. In 190, a part of the city of Rome burned, and Commodus took the opportunity to "re-found" the city of Rome in his own honor, as Colonia Commodiana. The months of the calendar were all renamed in his honor, and the senate was renamed as the Commodian Fortunate Senate. The army became known as the Commodian Army. Commodus was strangled in his sleep in 192, a day before he planned to march into the Senate dressed as a gladiator to take office as a consul. Upon his death, the Senate passed damnatio memoriae on him and restored the proper name to the city of Rome and its institutions. The popular movies The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964) and Gladiator (2000) were loosely based on the career of the emperor Commodus, although they should not be taken as an accurate historical depictions of his life.

The Severan dynasty, 193 - 235 CE

The Severan dynasty includes the increasingly troubled reigns of Septimius Severus (193–211), Caracalla (211–217), Macrinus (217–218), Elagabalus (218–222), and Alexander Severus (222–235). The founder of the dynasty, Lucius Septimius Severus, belonged to a leading native family of Leptis Magna in Africa who allied himself with a prominent Syrian family by his marriage to Julia Domna. Their provincial background and cosmopolitan alliance, eventually giving rise to imperial rulers of Syrian background, Elagabalus and Alexander Severus, testifies to the broad political franchise and economic development of the Roman empire that had been achieved under the Antonines. A generally successful ruler, Septimius Severus cultivated the army's support with substantial remuneration in return for total loyalty to the emperor and substituted equestrian officers for senators in key administrative positions. In this way, he successfully broadened the power base of the imperial administration throughout the empire. Abolishing the regular standing jury courts of Republican times, Septimius Severus was likewise able to transfer additional power to the executive branch of the government, of which he was decidedly the chief representative.

Septimius Severus' son, Marcus Aurelius Antoninus - nicknamed Caracalla - removed all legal and political distinction between Italians and provincials, enacting the Constitutio Antoniniana in 212 which extended full Roman citizenship to all free inhabitants of the empire. Caracalla was also responsible for erecting the famous Baths of Caracalla in Rome, their design serving as an architectural model for many subsequent monumental public buildings. Increasingly unstable and autocractic, Caracalla was assassinated by the praetorian prefect Macrinus in 217, who succeeded him briefly as the first emperor not of senatorial rank. The imperial court, however, was dominated by formidable women who arranged the succession of Elagabalus in 218, and Alexander Severus, the last of the dynasty, in 222. In the last phase of the Severan principate, the power of the Senate was somewhat revived and a number of fiscal reforms were enacted. Despite early successes against the Sassanian Empire in the East, Alexander Severus' increasing inability to control the army led eventually to its mutiny and his assassination in 235. The death of Alexander Severus ushered in a subsequent period of soldier-emperors and almost a half-century of civil war and strife.

Crisis of the third century, 235 - 275 CE

The Crisis of the 3rd Century is a commonly applied name for the crumbling and near collapse of the Roman Empire between 235 and 275 CE. During this period, Rome was ruled by more than 35 individuals, most of them prominent generals who assumed Imperial power over all or part of the empire, only to lose it by defeat in battle, murder, or death. After 35 years of this, the Empire was on the verge of death, and only the military skill of Aurelian, one of Rome's greatest emperors, restored the empire to its natural boundaries.

See: Crisis of the Third Century

Tetrarchy

(text is needed)

See: Tetrarchy

Christian Empire, 313 - 395 CE

The beginning of the roman empire as a christian empire probably lies in 313, with the Edict of Milan. The edict was signed under the reign of Constantine_I_of_the_Roman_Empire.

Late Antiquity in the West

In popular history, the year 476 AD is generally accepted as the end of the Western Roman Empire. In that year, Odoacer disposed of his puppet Romulus Augustulus (475-476 AD), and for the first time did not bother to induct a successor. The last Emperor who ruled from Rome, however, had been (xxx), who removed the seat of power to Mediolanum (Milan). Edward Gibbon, in writing The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire knew not to end his narrative at 476. The great corpse continued to twitch, into the 6th century.

On the other hand, in 409, with the Emperor of the West fled from Milan to Ravenna and all the provinces wavering in loyalties, the Goth Alaric I, in charge at Rome, came to terms with the senate, and with their consent set up a rival emperor and invested the prefect of the city, a Greek named Priscus Attalus, with the diadem and the purple robe. In the following year when the Goths rampaged in the City, local power was in the hands of the Bishop of Rome. The transfer of power to Christian pope and military dux had been effected: the Western Empire was effectively dead, though no contemporary knew it.

The next seven decades played out as aftermath. Theodoric the Great as King of the Goths, couched his legitimacy in diplomatic terms as being the representative of the Emperor of the East. Consuls were appointed regularly through his reign: a formula for the consular appointment is provided in Cassiodorus' Book VI. The post of consul was last filled in the west under Theodoric's successor, Athalaric, until he died in 534. Ironically the Gothic War in Italy, which was meant as the reconquest of a lost province for the Emperor of the East and a re-establishment of the continuity od power, actually caused more damage and cut more ties of continuity with the Antique world than the attempts of Theodoric and his minister Cassiodorus to meld Roman and Gothic culture within a Roman form.

In essence, the "fall" of the Roman Empire to a contemporary depended a great deal on where they were and their status in the world. On the great villas of the Italian Campagna, the seasons rolled on without a hitch. The local overseer may have been representing an Ostrogoth, then a Lombard duke, then a Christian bishop, but the rhythm of life and the horizons of the imagined world remained the same. Even in the decayed cities of Italy, consuls were still elected. In Auvergne, at Clermont, the Gallo-Roman poet and diplomat Sidonius Apollinaris, bishop of Clermont, realized that the local "fall of Rome" came in 475, with the fall of the city to the Visigoth Euric.In the north of Gaul, the Franks could not be taken for Roman, but in Hispania the last Arian Visigothic king Leovigild considered himself the heir of Rome. In Aquitania and Provence, the cities were not abandoned, but Roman culture in Britain collapsed in waves of violence after the last legions evacuated. In Athens the end came for some in 527, when the Emperor Justinian closed the Neoplatonic Academy; for other Greeks it had come in 396, when Christian monks led Alaric to vandalize the site of the Eleusinian mysteries.

From Roman to Byzantine in the East

The transition between one united empire to a divided Western and Eastern empire was a gradual transformation. In 285 AD, Diocletian became emperor of the Roman Empire. Diocletian felt that the system of Roman imperial government was unsustainable in the face of internal pressures and a military threat on two fronts. He gave Maximian the title of Caesar, which was the traditional form in which an emperor (Augustus) designated a successor. However, Diocletian soon made Maximian an Augustus as well. The imperial power was now divided between two people. Diocletian's sphere of influence was the east, and Maximian's the west. This division continued untill in 324 AD Constantine the Great became the sole emperor of the Roman Empire. He decided that the empire needed a new capital. He chose Byzantium for this. He refounded it as Nova Roma, but it was popularly called Constantinople, Constantine's City, and Istanbul in the east.

The defeat of the Battle of Adrianople in 378, along with the death of Emperor Valens, was a deciding moment in the division of the Empire. Valentinian I, brother of Valens, Emperor of the Western part of the Roman Empire, had designated his oldest son Gratianus Augustus. He was heir to the Western part of the Roman Empire. However on his father's death, troops in Pannonia declared his infant half-brother emperor under the title Valentinian II. Gratian acquiesced in their choice and administrated the Gallic part of the Western Empire. Italy, Illyria and Africa were officially administrated by his brother and his step-mother Justina, however the real authority rested with Gratianus. With his uncle's death, the eastern part of the empire became also his responsibility. 8 months later he promoted Theodosius I to govern the eastern part of the empire.

For some years Gratian governed the empire with energy and success, but gradually he sank into indolence. Magnus Maximus led a rebellion, defeating Gratianus. Gratianus had to flee, from Paris to Lyon. Through treachery of the Governor, he was handed over to the rebels and was assassinated on August 25, 383 AD. Valentinian II succeeded him, only twelve years old, but the Northern provinces stayed under Magnus Maximus rule. In 387 Magnus Maximus crossed the Alps into the valley of the Po and threatened Milan. Valentinian and his mother fled to Theodosius, the Emperor of the East and husband of Galla, Valentinian's sister. Valentinian was restored in 388 by Theodosius, through whose influence he was converted to Orthodox Catholicism. Theodosius continued supporting Valentinian and protecting him from a variety of usurpations. In 392 Valentinian was murdered in Vienne. Theodosius succeeded him, ruling the entire Roman Empire.

Theodosius had two sons and a daughter, Pulcheria, from his first wife, Aelia Flacilla. His daughter and wife died in 385 AD (can't discover the cause of dead, will search further). By his second wife, Galla, he had a daughter, Galla Placidia, the mother of Valentinian III, who would be Emperor of the West.

After his death in 395 AD, he gave the two halves of the Empire to his two sons Arcadius and Honorius; Arcadius became ruler in the East, with his capital in Constantinople, and Honorius became ruler in the west, with his capital in Milan. At this point, instead of 2 Emperors ruling the Roman Empire, there were now 2 Empires with each its own Emperor.

The Byzantine Empire was born, though it was never called this, rather it was called Romania or Basileia Romaion.

See also

General

- List of Ancient Rome-related topics

- List of Roman Emperors

- Five good emperors

- Byzantine Empire

- Byzantine Emperors

- Gallic Empire

- Pax romana

- Roman currency

- Roman Emperor

- Roman place names

- Roman provinces

- Societas Via Romana

Ancient Historians of the Empire

Writing in Latin

- Livy - his history is of the Roman Republic, but he wrote during the reign of Augustus

- Suetonius

- Tacitus

- Ammianus Marcellinus

Writing in Greek

Latin Literature of the Empire

External links

- Grout, James, "Encyclopaedia Romana".

- J. O'Donnell, Worlds of Late Antiquity website: links, bibliographies: Austine, Boethius, Cassiodorus etc.

References

18th and 19th century histories

Modern histories of the Roman Empire

- J. B. Bury, A History of the Roman Empire from its Foundation to the death of Marcus Aurelius (1913)

- J. A. Crook, Law and Life of Rome, 90 B.C. - A.D. 212 (1967)

- S. Dixon, The Roman Family (1992)

- Donald R. Dudley, The Civilization of Rome (2nd Edition) (1985)

- A.H.M. Jones, The Later Roman Empire, 284-602 (1964)

- A. Lintott, Imperium Romanum: Politics and administration (1993)

- R. Macmullen, Roman Social Relations, 50 B.C. to A.D. 284 (1974)

- M.I. Rostovtzeff, Economic History of the Roman Empire (2nd ed., 1957)

- R. Syme, The Roman Revolution (1939)

- C. Wells, The Roman Empire (2nd Edition) (1992)