Joseph Massino

Joseph Charles Massino | |

|---|---|

2003 FBI mugshot | |

| Born | January 10, 1943 New York City |

| Other names | Big Joey, The Ear |

| Occupation(s) | Mobster, food services |

| Criminal status | Turned state's evidence |

| Allegiance | Bonanno crime family |

| Conviction(s) | Labor racketeering (1986) Murder (2004, 2005) Arson, extortion, loansharking, illegal gambling, money laundering (2004) |

| Criminal penalty | 10 years imprisonment (1987) Life imprisonment (2005) |

Joseph Charles Massino (born January 10, 1943), is a former American mobster. He was a member of the American Mafia (Cosa Nostra) and served as the boss of the Bonanno crime family from 1991 to 2004, when he became the first boss of one of the Five Families in New York City to turn state's evidence.

Massino was a protégé of Phillip Rastelli, who took control of the troubled Bonanno family after the assassination of Carmine Galante. Massino secured his own power after arranging two 1981 gang murders, first a trio of rebel captains, then his rival Dominic Napolitano. In 1991, while imprisioned for a 1986 labor racketeering conviction, Rastelli died and Massino succeeded him. Upon his release the following year he reorganized the Bonannos as one of the strongest of the New York families. Massino became known as "The Last Don" as the only New York boss of his time who was out of prison.

In July 2004 Massino was finally convicted in a murder and racketeering indictment based on the testimony of several cooperating made men, including Massino's disgruntled underboss and brother-in-law Salvatore Vitale. He was also facing the death penalty for another murder case, but after agreeing to testify he was sentenced to life imprisonment instead in 2005. He testified for the first time in the 2011 murder trial of his acting boss Vincent Basciano, helping win a conviction against him.

Early years

Joseph Massino was born on January 10, 1943 in New York City.[1] He was one of three sons of the Neapolitan-American Anthony and Adeline Massino.[2] Raised in Maspeth, Queens,[2] Massino would admit to being a juvenile delinquent by the age of 12 and would claim at 14 he ran away from home to Florida.[3] He dropped out of Grover Cleveland High School in tenth grade.[4]

Massino first met his future wife Josephine Vitale in 1956,[2] and married her in 1960.[5] The couple had three daughters.[6] Massino also befriended Josephine's brother, Salvatore Vitale, who, after briefly serving in the Army, would become one of Massino's most trusted allies.[7] While athletic in youth[2] Massino, an avid cook,[8] would become overweight in adulthood. His weight gained him the nickname "Big Joey" and during a 1987 rakceteering trial, when he asked FBI agent Joseph Pistone who was to play him in a film adaptation of his undercover work, Pistone joked that they could not find anyone fat enough.[9] By 2004, Massino was suffering from diabetes and high blood pressure as well.[10]

After he turned state's evidence, Massino claimed his first murder victim was a Bonanno crime family associate named Tommy Zummo, who he shot dead some time in the 1960s. The killing gained the ire of a Maspeth-based Bonanno caporegime (captain, abbreviated capo), Phillip Rastelli, but he remained unaware of Massino's participation,[11] and a nephew of Rastelli ultimately helped Massino become his protégé.[12] Rastelli would set Massino up as a lunch wagon operator as part of his 'Workmen's Mobile Lunch Association', an effective protection racket; after paying a kickback to Rastelli in the form of membership dues, Massino was assured no competition where he operated.[13]

Bonanno crime family

Rise to power

By the late 1960s Massino was a Bonanno associate.[14] He led a successful truck hijacking crew, with the assistance of his brother-in-law Salvatore Vitale and carjacker Duane Leisenheimer, while fencing the stolen goods and running numbers using the lunch wagon as a front.[12][15] He also befriended another mob hijacker, the future Gambino crime family boss John Gotti.[16] Increasingly prosperous, Massino opened his own catering company, J&J Catering, which became another front for his activities.[5] Massino's mentor Rastelli was expected to become Bonanno boss upon the 1973 death of Natale Evola, but he had been convicted the previous year of loansharking and then of extortion in 1976, leaving him imprisoned.[17]

In 1975, Massino and Vitale participated in the murder of Vito Borelli, who Massino claimed was primarily executed by Gotti, at the behest of Paul Castellano of the Gambino crime family.[18] The Borelli hit was significant for Massino "making his bones" – proving his loyalty to the Mafia by killing on its behalf – putting him close to becoming a made man, a full member, in the Bonanno family.[19] Massino also arranged the murder of one of his hijackers, Joseph Pastore, in 1976 after having Vitale borrow $9,000 from him on his behalf. While later acquitted of the crime,[20] both Vitale and Massino would admit to participation after turning state's evidence.[11][21]

In March 1975, Massino was arrested at the scene of the arrest of one of his hijackers, Raymond Wean, and charged with conspiracy to receive stolen goods.[22] Massino was scheduled to go on trial in 1977, but the charges were dropped after he successfully argued that he had not been properly mirandized, disqualifying statements Massino gave to police from being used in trial.[23]

On June 14, 1977, Massino was inducted into the Bonanno family along with Anthony Spero, Joseph Chilli, Jr. and a group of other men in a ceremony conducted by Carmine Galante, then acting boss of the Bonanno family.[11] He worked as a soldier in James Galante's crew, and later worked in Philip "Phil Lucky" Giaccone's crew.[24] Massino nevertheless remained loyal to Rastelli, then vying to oust Galante despite his imprisonment. Fearing Galante wanted him dead for insubordination, Massino delivered a request to the Commission, the governing body of the American Mafia, on Rastelli's behalf to have Galante killed. The hit was approved and executed on July 12, 1979; Rastelli subsequently took full control of the family and rewarded Massino's loyalty by promoting him to capo.[25]

By the beginning of the 1980s Massino ran his crew from the J&S Cake social club, a property just behind J&J Catering.[5][26]

Three capos and Napolitano murders

Following the Galante hit, Massino began jockeying for power with Dominic "Sonny Black" Napolitano, another Rastelli loyalist capo. Both men were themselves threatened by another faction seeking to depose the absentee boss led by capos Alphonse "Sonny Red" Indelicato, Dominick "Big Trin" Trincera and Phillip Giaccone.[27] The Commission initially tried to maintain neutrality, but in 1981, Massino got word from his informants that the three capos were stocking up on automatic weapons and planning to kill the Rastelli loyalists within the Bonanno family to take complete control. Massino turned to Colombo crime family boss Carmine Persico and Gambino boss Paul Castellano for advice; they told him to act immediately.[27]

Massino and Napolitano arranged a sit-down with the three capos for May 5, 1981 to ambush them.[28] When the three capos arrived with Frank Lino to meet Massino, four masked gunmen, including Vitale and Bonanno-affiliated Montreal boss Vito Rizzuto, burst out of a closet. Trinchera, Giaccone and Indelicato tried to escape but were shot to death, with Massino himself stopping Indelicato from escaping.[18][29] Lino escaped unscathed by running out the door.[29] The hit further improved Massino's prestige, but was marred by both Lino's escape and the discovery of Indelicato's body on May 20.[30][31]

Massino quickly won Lino over to his side,[32] but Indelicato's son Anthony "Bruno" Indelicato vowed revenge.[33] Napolitano assigned associate Donnie Brasco, who he hoped to make a made man, to kill Indelicato.[33] 'Brasco', however, was in fact an undercover FBI agent named Joseph Pistone; shortly after the hit was ordered Pistone's assignment was ended and Napolitano was informed of their infiltration.[34]

Already skeptical of Napolitano's support of 'Brasco',[34] Massino was deeply disturbed by the breach of security when he learned of the agent's true identity.[35] Vitale would later testify that this was the reason Massino subsequently decided to murder Napolitano as well; as he would later quote Massino, "I have to give him a receipt for the Donnie Brasco situation."[36] On August 17 the former renegade Frank Lino and Steven Cannone drove Napolitano to the house of Ronald Filocomo, a Bonanno family associate, for a meeting. Napolitano was greeted by captain Frank Coppa, then thrown down the stairs to the house's basement by Lino and shot to death.[37] While Napolitano's body was prepared for disposal, Lino went outside to a nearby van and told the occupants that Napolitano was dead. One of the men in the car was Massino.[38] Napolitano's body was discovered the following year.[39]

Benjamin "Lefty" Ruggiero, who helped Pistone formally become a Bonanno associate, was also targeted, but was arrested en route to the meeting where he was expected to be murdered. On February 18, 1982, Anthony Mirra, the soldier who first 'discovered' Pistone, was assassinated on Massino's orders. Mirra had gone into hiding upon Pistone's exposure but was ultimately betrayed and murdered by his protégé and cousin Joseph D'Amico.[37]

Fugitive and Bonventre murder

On November 23, 1981, based on information gained by Pistone's infiltration, six Bonanno mobsters, including the then-missing Napolitano, were indicted on racketeering charges and conspiracy in the three capos hit.[40]

In March 1982, Massino was tipped off by a Colombo-associated FBI insider that he was about to be indicted and went into hiding in Pennsylvania with Leisenheimer.[3][41][42] On March 25, 1982, Massino was also charged with conspiracy to murder Indelicato, Giaccone and Trinchera and truck hijacking.[42] In hiding, Massino was able to see the prosecution's strategy and better plan his defense as well as eventually face trial without association with other mobsters.[43][44] Pistone later speculated Massino also feared retaliation upon the revelation that his associate Raymond Wean had turned state's evidence.[45] Massino was visited by many fellow mobsters, including Gotti,[46] and Vitale would secretly deliver cash to support him.[42]

In 1984, Rastelli was released from prison,[47] and he and Massino ordered the murder of Bonanno soldier Cesare Bonventre.[48] Still a fugitive, Massino summoned Vitale, Louis Attanasio and James Tartaglione to his hideout and gave them the order.[47] By this time, Massino was considered by most mobsters to be the boss in all but name, even though Rastelli was still officially head of the family,[48] as well as heir apparent for the title itself.[49] According to Vitale, Massino had Bonventre killed for giving him no support when he was in hiding.[50]

Bonventre was called to a meeting with Rastelli in Queens. He was picked up by Vitale and Attanasio and driven to a garage. En route, Attanasio shot Bonventre twice in the head but only wounded him; he would kill Bonventre with two more shots when they reached their destination.[47] The task of disposing of Bonventre's corpse was handed to Gabriel Infanti. Infanti promised Vitale that Bonventre's remains would disappear forever. However, after a tipoff, the remains were discovered on April 16, 1984, in a warehouse in Garfield, New Jersey, stuffed into two 55-gallon glue drums.[47]

For his part in the hit, Massino had Vitale initiated into the Bonanno family.[48]

1986 conviction and 1987 acquittal

Through Gotti associate Angelo Ruggiero, Massino was able to meet with defense attorney John Pollok in 1984 to negotiate his surrender. He finally turned himself in on July 7 and was released on $350,000 bail.[51] That year, Massino and Salvatore Vitale secured no-show jobs with the Long Island based King Caterers in exchange for protecting them from Lucchese extortion.[52]

In 1985 Massino was indicted twice more, first as a co-conspirator with Rastelli in a labor racketeering case for controlling the Teamsters Local 814, then with a conspiracy charge for the Pastore murder that was added to the original three capos indictment. The second indictment also charged Vitale as a co-conspirator in the hijacking cases.[53][54]

The labor racketeering trial began in April 1986,[53] with Massino as one of twelve defendants including Rastelli and former underboss Nicholas Marangello.[55] While Massino protested in confidence to other mobsters he never had the opportunity to profit from the racket, he was implicated by both Pistone and union official Anthony Gilberti, and on October 15, 1986 was found guilty of racketeering charges for accepting kickbacks on the Bonannos' behalf.[55][56] On January 16, 1987 Massino was sentenced to ten years imprisonment, his first prison term.[56] Rastelli, also convicted and in poor health during the trial, was sentenced to twelve.[56] Around this time Massino was believed to be the Bonanno family's official underboss.[57]

On April 1987, Massino and Vitale went on trial for truck hijacking and conspiracy to commit the triple murder, defended by Samuel H. Dawson and Bruce Cutler respectively. Prosecutor Michael Chertoff, describing Massino's rise in his opening statements, would characterize him as the "Horatio Alger of the mob."[58] Raymond Wean and Joseph Pistone testified against Massino, but both proved unable to conclusively link Massino with any of the murder charges.[20] On June 3, while both men were convicted on hijacking charges they were cleared of the murder conspiracy charges. Further, the only proven criminal acts took place outside the RICO act's five year statute of limitations; without evidence that the "criminal enterprise" was still active in this timeframe the jury returned a special verdict clearing Massino and Vitale of these charges as well.[20][59]

During Massino's imprisonment at Talladega Federal Prison for his 1986 conviction Vitale functioned as his messenger, effectively becoming co-acting boss alongside consigliere Anthony Spero.[60] On Massino's orders, Vitale would murder Gabriel Infanti, who had also botched a 1982 hit on Anthony Gilberti and was suspected of being an informant.[60]

Bonanno boss

The family regroups

Shortly before the death of Rastelli in 1991, Massino had ordered Vitale to "make me boss."[60] By that time, however, Massino was already the family's underboss and there were no other obvious candidates. Spero subsequently called a meeting of the family's capos, and Massino was elected unopposed as boss.[60] Upon his release on November 13, 1992 Massino retained Vitale as his messenger during his probation and promoted him to underboss.[61][62] He returned to his job at King Caterers,[52] and in 1996 became co-owner of Casablanca, a well-reviewed Maspeth Italian restaurant.[63][64]

Massino was determined to avoid the pitfalls that landed other Mafia chieftains in prison. Inspired by Genovese boss Vincent Gigante, Massino ordered his men to touch their ears when referring to him and never say his name out loud due to FBI surveillance. Massino gained the nickname "The Ear" because of this.[65] Massino took a great number of precautions in regards to security and the possibility of anything incriminating being picked up on a wiretap. He closed the long-standing social clubs of the Bonanno family.[66] Massino also arranged family meetings to be conducted in remote locations within the United States and in some instances a foreign country.[67] Remembering how Pistone's infiltration had nearly destroyed the family, he also decreed that all prospective made men had to have a working relationship with an incumbent member for at least eight years before becoming made, in hopes of ensuring new mafiosi were as reliable as possible.[65] Unusually for bosses of his era, he actively encouraged his men to have their sons made as well. In Massino's view, this would make it less likely that a capo would turn informer, since if that happened the defector's son would face almost certain death.[65]

To minimize the damage from informants or undercover investigations Massino introduced a clandestine cell system for his crews, forbidding them from contacting one another and avoiding meeting their capos.[66][68] He would instead create a new committee that would relay his orders to the crews.[68] In contrast to his contemporaries, particularly the publicity-friendly John Gotti and the conspicuous feigned insanity of Vincent Gigante, Massino himself was also able to operate with a relatively low public profile;[1][9] both Pistone and mob writer Jerry Capeci would consequently refer to Massino as the "last of the old-time gangsters."[1][9]

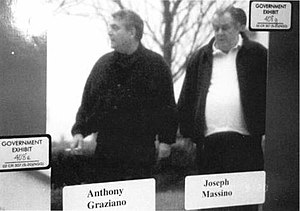

A side effect of these reforms was the reduction of Vitale, in his own words, to "a figurehead."[69] By the time of Massino's release the Bonanno family had grown tired of Vitale, regarding him as greedy and overstepping his authority.[70] In the new structure of the family, Vitale lost the underboss's usual role as a go-between for the boss, and Massino made it clear to Vitale his unpopularity was a factor in these changes.[70][71] Vitale remained loyal,[71] however, and helped Massino organize the March 18, 1999 murder of Gerlando Sciascia. Sciascia, a Sicilian-born capo linked to the Montreal Rizzuto crime family, had accused fellow Massino-confidant capo Anthony Graziano of using cocaine, and Massino ultimately sided with Graziano in their feud.[72][73]

Shortly after becoming boss, Massino announced that his men should no longer consider themselves as part of the Bonanno family. Instead, he renamed it the Massino family, after himself. He was angered at family namesake Joseph Bonanno's tell-all autobiography, A Man of Honor, and regarded it as a violation of the code of omertà.[74][75] The new name was first disclosed after Massino was indicted in 2003 and did not catch on outside the Mafia.[74][76]

Relations with other families

When Massino took over the Bonanno family his relationship with John Gotti had declined. Gotti, who at one point tried to get Massino a seat on the Commission as Bonanno acting boss,[77] was reportedly infuriated that Massino had been formally appointed without him being consulted.[64] Massino would later testify he believed Gotti conspired with Vitale to kill him.[78] Gotti, however, was marginalized by his 1992 racketeering and murder conviction and consequent life imprisonment.[79] Massino, for his own part, would denounce Gotti for killing his own boss Paul Castellano and keeping a high public profile.[80]

The Bonanno family's influence had diminished following the 1966 ousting of Joseph Bonanno and it was kicked off the Commission altogether following Pistone's infiltration.[81] By the late 1990s the situation was reversed; Massino was the only boss of the Five Families who was not in jail,[82] and his family was considered one of the most powerful in New York.[9][83] Wary of surveillance, Massino generally avoided meeting with members of other Mafia families[65] and encouraged his crews to operate independently as well.[66] In January 2000, however, Massino did preside over an informal Commission meeting with the acting bosses of the other four families.[84]

According to Capeci, the murder of Sciascia soured relations between the Bonanno and Rizzuto families.[85] Originally considered merely a Canadian Bonanno crew,[86] the Rizzutos responded by taking even less heed from New York.[85]

Run-up to prosecution

At the beginning of his reign as boss, Massino enjoyed the benefit of limited FBI attention. In 1987, with the Bonannos weakened, the FBI merged its Bonanno squad with its Colombo family squad,[87] and this squad was initially preoccupied with the Colombos' third internal war.[88] Another dedicated Bonanno squad would be established in 1996.[89]

The FBI began to target the Bonanno administration. In 1995, consigliere Anthony Spero was sentenced to two years imprisonment after being convicted of loansharking,[90] then to life imprisonment in 2002 for murder.[91] Graziano would assume Spero's duties, but he too plead guilty to racketeering charges in December 2002 and was sentenced to 10 years imprisonment.[92] Vitale would also plead guilty to loansharking in June 2002,[93] and was put under house arrest awaiting sentencing.[71]

Until 2002, no made member of the Bonannos had turned state's evidence, and Massino used this as a point of pride to rally his crime family.[94] That year Frank Coppa, convicted on fraud and facing further charges, became the first to flip.[95] He was followed shortly by Richard Cantarella, a participant in the Mirra murder,[37] who was facing racketeering and murder charges.[96] A third, Joseph D'Amico, subsequently turned state's evidence with the knowledge that Cantarella could implicate him for murder as well.[97] All of these defections helped leave Massino, at last, vulnerable to serious charges.[98]

2004 conviction

On January 9, 2003, Massino was arrested and indicted, alongside Vitale, Frank Lino and capo Daniel Mongelli, in a comprehensive racketeering indictment. The charges against Massino himself included ordering the 1981 murder of Napolitano.[99][100] Massino was denied bail,[101] and Vincent Basciano took over as acting boss in his absence.[102] Massino hired David Breitbart, an attorney he had originally wanted to represent him in his 1987 trial, for his defense.[103]

Three more Bonanno made men would choose to cooperate before Massino came to trial. The first was James Tartaglione; anticipating he would shortly be indicted as well he went to the FBI and agreed to wear a wire while he remained free.[104] The second was Salvatore Vitale. Prior to their arrests Massino had contemplated killing Vitale, suspecting he had turned state's evidence after his 2002 guilty plea, and in custody he again put out the word, to a receptive Bonanno family, that he wanted Vitale killed.[105] After learning of the first plot from Coppa and Cantarella, prosecutors informed Vitale.[105] Vitale was already dissatisfied by the lack of support he and his family received from Massino after his arrest,[106] and, by the end of February, indeed decided to testify.[105][107] He was followed in short order by Lino, knowing Vitale could implicate him in murder as well.[104] Also flipping was longtime Bonanno associate Duane Leisenheimer, concerned for his safety after an investigator for Massino's defense team visited to find out if he intended to flip.[108]

With these defections, Massino was implicated and charged with seven more murders: the three capos (this time for participation in the murder itself rather than conspiracy),[109] Mirra,[110] Bonventre, Infanti and Sciascia.[101] Of particular interest was the Sciascia hit, which took place after a 1994 amendment to racketeering laws that allowed the death penalty for murder in aid of racketeering.[111]

Massino's trial began on May 24, 2004, with judge Nicholas Garaufis presiding and Greg D. Andres and Robert Henoch heading the prosecution.[112] He now faced 11 RICO counts for seven murders (due to a technicality, the Sciascia case was severed to be tried separately), arson, extortion, loansharking, illegal gambling, and money laundering.[113] By this time, Time Magazine had dubbed Massino as "the Last Don," in reference to his status as the only New York boss to evade conviction up to that point.[9][114] The name stuck.[115][116][117]

Despite a weak start, with opening witness Anthony Gilberti unable to recognize Massino in the courtroom,[118] the prosecution would establish its case to link Massino with the charges in the indictment through an unprecedented seven major turncoats,[119] including the six turned made men.[115] Salvatore Vitale, the last of the six to take the stand, was of particular significance as his closeness to his brother in law allowed him to cover Massino's entire criminal history in his testimony.[120] Brietbart's defense rested primarily on cross-examination of the prosecution witnesses, with his only witness being an FBI agent to challenge Vitale's reliability.[121] His defense was also unusual in that he made no attempt to contest that Massino was the Bonanno boss, instead stressing the murders in the case took place before he took over and that Massino himself "showed a love of life...because the murders ceased."[122]

After deliberating for five days the jury found Massino guilty of all eleven counts on July 30, 2004.[115] The jury also approved the prosecutors' recommended $10 million forfeiture of the proceeds of his reign as Bonanno boss later that day.[123]

Turning state's evidence

Immediately after his July 30 conviction, as court was adjourned, Massino requested a meeting with Judge Garaufis, where he made his first offer to cooperate.[124] He was facing the death penalty if found guilty of Sciascia's murder – indeed, one of John Ashcroft's final acts as Attorney General was to order federal prosecutors to seek the death penalty for Massino.[125] However, Massino subsequently claimed he decided to turn informer due to the prospect of his wife and mother having to forfeit their houses to the government.[126] Mob authors and journalists Anthony D. DeStefano and Selwyn Raab both consider the turning of so many made men as a factor in disillusioning Massino with Cosa Nostra,[124][127] the former also assuming Massino had decided to flip "long before the verdict".[124] Massino was the first sitting boss of a New York crime family to turn state's evidence, and the second in the history of the American Mafia to do so [128] (Philadelphia crime family boss Ralph Natale had flipped in 1999 when facing drug charges[129]). It also marked the second time in a little more than a year that a New York boss had reached a plea bargain; Gigante had pleaded guilty to obstruction of justice charges in 2003 after prosecutors unmasked his long charade of feigning insanity.[130]

At his advice, that October the FBI revisited the Queens mob graveyard where Alphonse Indelicato's body was found, and unearthed the bodies of Trinchera and Giaccone as well.[131] They also hoped to find the body of John Favara, who accidentally killed Gotti's son, and the body of Tommy DeSimone, murdered in 1979 for killing William Devino and Ronald Jerothe.[132] Massino also reported that Vincent Basciano, arrested in November, had conspired to kill prosecutor Greg Andres, but after failing a polygraph test regarding the discussion he agreed to wear a wire when meeting the acting boss in jail.[133] While Massino was unable to extract an unambiguous confession regarding Andres, he did record Basciano freely admit to ordering the murder of associate Randolph Pizzolo.[133][134]

By the end of January 2005, when Basciano was indicted for the Pizzolo murder, Massino was identified by news sources as the then-anonymous fellow mobster who secretly recorded his confession,[135][136] to the public disgust of his family.[137] Further confirmation of Massino's defection came in February as he was identified as the source for the graveyard,[138] then in May when the Justice Department dropped the threat of the death penalty regarding the Sciascia case.[139] In a hearing on June 23, 2005, Massino finalized his deal and plead guilty to ordering the Sciascia murder. For this and his 2004 conviction he was sentenced to life imprisonment, with a possible reduction depending on his service as a witness.[140][141] That same day Josephine Massino negotiated a settlement to satisfy the forfeiture claim, keeping the homes of herself and Massino's mother as well as some rental properties while turning over, among other assets, a cache of $7 million and hundreds of gold bars, and the Casablanca restaurant.[126][140]

Massino was conspicuously absent from the prosecution witnesses at the 2006 racketeering trial of Basciano, the prosecution deciding he was not yet needed;[142] he was also expected to testify against Vito Rizzuto regarding his role in the three capos murder, but the Montreal boss accepted a plea bargain in May 2007.[86] He finally made his debut as a witness at Basciano's trial for the murder of Randolph Pizzolo in April 2011;[143] Massino's testified both during the trial itself and, after Basciano was convicted, on behalf of the prosecution's unsuccessful attempt to impose the death penalty.[133][144] During his testimony Massino noted that he hoped, as a result of his cooperation, "I’m hoping to see a light at the end of the tunnel."[3]

Notes

- ^ a b c Getlin, Josh (2004-05-03). "A Simple Queens Caterer, or 'Big Joey' the Mob Killer?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2012-05-22.

- ^ a b c d DeStefano, pp. 42–43

- ^ a b c Rashbaum, William (2011-04-12). "A Mafia Boss Breaks a Code in Telling All". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-03-20.

- ^ Raab, p. 604

- ^ a b c Crittle, pp. 49–51

- ^ Crittle, p. 211

- ^ Crittle, pp. 136–137

- ^ Crittle, p. 10

- ^ a b c d e Richard Corliss (2004-03-29). "The Last Don". Time. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Marzulli, John (2004-12-28). "Jail's Got Mobster Steamed Up". New York Daily News. Retrieved 2012-03-21.

- ^ a b c DeStefano, Anthony. "Bonanno Crime Family". tonydestefano.com. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- ^ a b Raab, p. 605

- ^ DeStefano, pp. 58–59

- ^ DeStefano, pp. 60–61

- ^ DeStefano, pp. 63–64, 68

- ^ Raab, p. 606

- ^ DeStefano, pp. 65, 67, 70

- ^ a b Mitchel Maddux; Jeremy Olshan (2011-04-13). "Nomerta! Mafia boss a squealer". New York Post. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ DeStefano, p. 74

- ^ a b c DeStefano, pp. 187–188

- ^ DeStefano, pp. 75–77

- ^ DeStefano, pp. 79–82

- ^ DeStefano, pp. 84–86

- ^ Lamothe, Humphreys, p. 87

- ^ Raab, pp. 607–608

- ^ DeStefano, p. 104

- ^ a b DeStefano, pp. 99, 101–103

- ^ Raab, p. 610

- ^ a b Raab, pp. 611–613

- ^ Crittle, pp. 86, 92

- ^ DeStefano, pp. 114–115

- ^ Raab, p. 615

- ^ a b DeStefano, pp. 112, 117

- ^ a b DeStefano, pp. 118–120

- ^ Crittle, pp. 98–99

- ^ Marzulli, John (2004-06-30). "Says Massino OKd '81 mob hit". New York Daily News. Retrieved 2012-03-24.

- ^ a b c Raab, pp. 617–620

- ^ DeStefano, p. 127

- ^ Crittle, pp. 102–104

- ^ DeStefano, p. 136

- ^ Hays, Tom (2011-04-14). "Joseph Massino, Ex Mob Boss: FBI Agent Told Us About Arrests". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 2012-03-20.

- ^ a b c DeStefano, pp. 140–142

- ^ Pistone, Brandt, p. 122

- ^ DeStefano, p. 167

- ^ Pistone, Brandt, pp. 103–104

- ^ Crittle, p. 114

- ^ a b c d DeStefano, pp. 160–163

- ^ a b c Raab, pp. 626–627

- ^ Pistone, Brandt, p. 317

- ^ Lamothe, Humphreys, p. 150

- ^ DeStefano, pp. 164–168

- ^ a b Raab, pp. 642–643

- ^ a b DeStefano, pp. 174–176

- ^ Raab, pp. 628–629

- ^ a b Raab, pp. 630–631

- ^ a b c DeStefano, pp. 178–179

- ^ Buder, Leonard (1987-08-27). "Civil Suit Is Filed By U.S. to Curb A Crime Family". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-03-22.

- ^ Lubasch, Arnold (1987-04-30). "Defendent Linked to Mob Murder Plot". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-03-29.

- ^ Lubasch, Arnold (1987-06-04). "2 Win Unusual Acquittals In Mafia Racketeering Trial". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-03-23.

- ^ a b c d Raab, pp. 633–635, 637

- ^ Crittle, p. 156

- ^ Raab, p. 638

- ^ Raab, p. 646

- ^ a b McPhee, Michele (2000-09-17). "Reputed Bonanno leader keeps low profile". New York Daily News. Retrieved 2012-03-24.

- ^ a b c d Raab, pp. 639–640

- ^ a b c Crittle, pp. 164–165

- ^ Sifakis, p. 306

- ^ a b Crittle, pp. 166–167

- ^ Crittle, p. 179

- ^ a b Crittle, pp. 175–176

- ^ a b c Raab, pp. 654–655

- ^ Raab, pp. 650–651

- ^ Paul Cherry; Andy Riga (2010-11-15). "Huge turnout for funeral of alleged Montreal Mafia don". Nanaimo Daily News. Retrieved 2012-03-29.

- ^ a b Crittle, p. 168

- ^ DeStefano, p. 17

- ^ Marzulli, John (2003-10-20). "Yes, we have no Bonannos First mob family to change names in 40 years! They call 'em the Massinos now". New York Daily News. Retrieved 2012-05-24.

- ^ Raab, p. 409

- ^ Mitchel Maddux; Jeremy Olshan (2011-04-19). "Gotti's plan to whack me". New York Post. Retrieved 2012-03-24.

- ^ Raab, Selwyn (1995-09-03). "With Gotti Away, the Genoveses Succeed the Leaderless Gambinos". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-03-26.

- ^ Marzulli, John (2004-06-30). "Bonanno Chief: Gotti Too Talky". New York Daily News. Retrieved 2012-03-28.

- ^ Raab, p. 602

- ^ Raab, p. 645

- ^ Raab, Selwyn (2000-04-29). "A Mafia Family's Second Wind; Authorities Say Bonannos, All but Written Off, Are Back". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-08-04.

- ^ Marzulli, John (2011-04-16). "Boss rat Joseph Massino admits to court that Mafia Commission hasn't met in 25 years". New York Daily News. Retrieved 2012-03-28.

- ^ a b Capeci, Jerry (2010-01-11). "Mob Murder In Montreal Could Trigger Bloodshed In New York". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 2012-03-29.

- ^ a b "Canada's top mob boss gets 10 years in New York court". Montreal Gazette. 2007-05-04. Retrieved 2012-03-24.

- ^ Crittle, p. 135

- ^ DeStefano, p. 192

- ^ Raab, p. 603

- ^ Capeci, Jerry (1995-05-03). "Gambino Bigfoot's Toe Woes". New York Daily News. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

- ^ Marzulli, John (2002-04-16). "Metropolitan Report Judge Nixes Gag Order In Louima Trial". New York Daily News. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

- ^ John Marzulli; Leo Standora (2002-12-24). "S.i. Wiseguy Grins & Will Bear It In Jail". New York Daily News. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

- ^ Lambert, Bruce (2002-06-15). "Four Admit Using Bank to Launder Money". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-03-31.

- ^ Marzulli, John (2005-04-10). "The Rise & Fall Of New York's Last Don. Pale. Bloated. Shuffling". New York Daily News. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- ^ DeStefano, pp. 204–206

- ^ Crittle, pp. 234–235

- ^ Raab, p. 677

- ^ DeStefano, p. 207

- ^ Rashbaum, William (2003-01-10). "Reputed Boss Of Mob Family Is Indicted". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- ^ Marzulli, John (2003-01-10). "Top Bonanno Charged In '81 Mobster Rubout". New York Daily News. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- ^ a b Marzulli, John (2003-08-21). "Feds Mull Whacking Mobster". New York Daily News. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ Robbins, Liz (2011-04-14). "Ex-Mob Boss Tells Jury, Calmly, About Murders". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ DeStefano, pp. 220–221

- ^ a b DeStefano, pp. 230–232

- ^ a b c Raab, pp. 674–675

- ^ Marzulli, John (2004-07-02). "Mob Rat: Boss is Kin, But He Don Me Wrong". New York Daily News. Retrieved 2012-05-02.

- ^ DeStefano, p. 222

- ^ Raab, pp. 678–679

- ^ Derek Rose; John Marzulli (2003-10-01). "Feds Bite Mobbed-up Cafe". New York Daily News. Retrieved 2012-04-20.

- ^ Marzulli, John (2003-05-31). "Bonanno Slaying Bust New Whacking Charge Vs. Reputed Boss". New York Daily News. Retrieved 2012-04-20.

- ^ Crittle, p. 34

- ^ Glaberson, William (2004-05-25). "Grisly Crimes Described by Prosecutors as Mob Trial Opens". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-04-20.

- ^ Raab, p. 679

- ^ Glaberson, William (2004-05-23). "An Archetypal Mob Trial: It's Just Like in the Movies". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-05-23.

- ^ a b c Glaberson, William (2004-07-31). "Career of a Crime Boss Ends With Sweeping Convictions". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-04-16.

- ^ Daly, Michael (2004-05-26). "Smoking Out the Real Killers". New York Daily News. Retrieved 2012-04-21.

- ^ Leonard, Tom (2009-03-06). "New York's mafia under threat as 'code of silence' is broken". The Telegraph. Retrieved 2012-05-23.

- ^ DeStefano, pp. 258–259

- ^ Raab, p. 681

- ^ Marzulli, John (2004-07-29). "Mob Betrayal Cuts Deep". New York Daily News. Retrieved 2012-05-02.

- ^ Raab, p. 684

- ^ Marzulli, John (2004-07-23). "Massino Not Boss During Hits: Att'y". New York Daily News. Retrieved 2012-05-02.

- ^ DeStefano, p. 312

- ^ a b c DeStefano, pp. 314–315

- ^ Glaberson, William (2004-11-13). "Judge Objects to Ashcroft Bid for a Mobster's Execution". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-04-21.

- ^ a b Marzulli, John (2011-04-14). "Joseph Massino, ex-Bonanno crime boss turned mob rat, gave feds $7 million he hid in his attic". New York Daily News. Retrieved 2012-04-23.

- ^ Raab, p. 687

- ^ Raab, p. 688.

- ^ Braun, Stephen (2001-05-04). "This Mob Shot Its Brains Out". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2012-05-05.

- ^ Raab, pp. 596–597

- ^ DeStefano, pp. 316–317

- ^ "Feds Search 'Mafia Graveyard' in New York". foxnews.com. New York Post. 2004-10-05. Retrieved 2012-03-21.

- ^ a b c Moynihan, Colin (2011-05-25). "Ex-Mob Boss Says Deputy Sought to Kill Prosecutor". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- ^ Marzulli, John (2011-04-14). "Ex-Bonanno Mafia boss Joseph Massino was scared of his wife, recordings reveal". New York Daily News. Retrieved 2012-04-26.

- ^ "Sources: Mafia Boss Spills Beans to FBI". Foxnews.com. Associated Press. 2005-01-28. Retrieved 2012-04-26.

- ^ Marzulli, John (2005-01-28). "Mob Boss A Rat Say Massino Wore Wire To Bust Chief In Rubout Plot". New York Daily News. Retrieved 2012-04-26.

- ^ DeStefano, p. 320

- ^ Capeci, Jerry (2005-02-03). "Massino's Tips Lead the FBI To Dig Deep". New York Sun. Retrieved 2012-04-26.

- ^ Marzulli, John (2005-05-07). "Massino Rats His Way Out Of Fed Death Trap". New York Daily News. Retrieved 2012-04-26.

- ^ a b DeStefano, pp. 321–325

- ^ Worth, Robert (2005-06-24). "Bonanno Crime Boss Is Sentenced to 2 Life Terms". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

- ^ Marzulli, John (2006-03-01). "Massino Won't Sing At Mob Trial". New York Daily News. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- ^ Rashbaum, William (2011-04-18). "At a Mob Trial, Testimony Focuses on the Knife and Fork". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- ^ John Marzulli; Larry McShane (2011-06-01). "Mob boss Vincent (Vinny Gorgeous) Basciano dodges death penalty, sentenced to life in prison". New York Daily News. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

References

- Crittle, Simon (2006). The Last Godfather: The Rise and Fall of Joey Massino. New York: Berkley. ISBN 0-425-20939-3.

- DeStefano, Anthony (2006). King of the Godfathers: "Big Joey" Massino and the Fall of the Bonanno Crime Family (2007 paperback ed.). New York: Pinnacle Books. ISBN 978-0-7860-1893-2.

- Lamothe, Lee (2006). The Sixth Family: The Collapse of the New York Mafia and the Rise of Vito Rizzuto. Mississuaga: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-15445-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Pistone, Joseph (2007). Donnie Brasco: Unfinished Business. Philadelphia: Running Press. ISBN 978-0-7624-2707-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Raab, Selwyn (2005). Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America's Most Powerful Mafia Empires (2006 revised ed.). New York: Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 978-0-312-36181-5.

- Sifakis, Carl (1987). The Mafia Encyclopedia (2005 ed.). New York: Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8160-6989-7.

External links

- 1943 births

- American arsonists

- American mob bosses

- American mobsters of Italian descent

- American money launderers

- American people convicted of murder

- American prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment

- Bonanno crime family

- Bosses of the Bonanno crime family

- Capi di tutti capi

- Living people

- Mobsters sentenced to life imprisonment

- People convicted of racketeering

- People convicted of murder by the United States federal government

- People from Queens

- Prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment by the United States federal government