Cashew

| Cashew | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cashews ready for harvest in Kollam, India | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | A. occidentale

|

| Binomial name | |

| Anacardium occidentale | |

The cashew is a tree in the family Anacardiaceae. Its English name derives from the Portuguese name for the fruit of the cashew tree, caju, which in turn derives from the indigenous Tupi name, acajú. Originally native to Northeast Brazil, it is now widely grown in tropical climates for its cashew seeds and cashew apples.

Etymology

The name Anacardium refers to the shape of the fruit, which looks like an inverted heart (ana means "upwards" and -cardium means "heart"). In the Tupian languages acajú means "nut that produces itself".[1]

Habitat and growth

The tree is small and evergreen, growing to 10-12m (~32 ft) tall, with a short, often irregularly shaped trunk. The leaves are spirally arranged, leathery textured, elliptic to obovate, 4 to 22 cm long and 2 to 15 cm broad, with a smooth margin. The flowers are produced in a panicle or corymb up to 26 cm long, each flower small, pale green at first then turning reddish, with five slender, acute petals 7 to 15 mm long. The largest cashew tree in the world covers an area of about 7,500 square metres (81,000 sq ft).

The fruit of the cashew tree is an accessory fruit (sometimes called a pseudocarp or false fruit). What appears to be the fruit is an oval or pear-shaped structure, a hypocarpium, that develops from the pedicel and the receptacle of the cashew flower.[3] Called the cashew apple, better known in Central America as "marañón", it ripens into a yellow and/or red structure about 5–11 cm long. It is edible, and has a strong "sweet" smell and a sweet taste. The pulp of the cashew apple is very juicy, but the skin is fragile, making it unsuitable for transport. In Latin America, a fruit drink is made from the cashew apple pulp which has a very refreshing taste and tropical flavor that can be described as having notes of mango, raw green pepper, and just a little hint of grapefruit-like citrus.

The true fruit of the cashew tree is a kidney or boxing-glove shaped drupe that grows at the end of the cashew apple. The drupe develops first on the tree, and then the pedicel expands to become the cashew apple. Within the true fruit is a single seed, the cashew nut. Although a nut in the culinary sense, in the botanical sense the nut of the cashew is a seed. The seed is surrounded by a double shell containing an allergenic phenolic resin, anacardic acid, a potent skin irritant chemically related to the more well known allergenic oil urushiol which is also a toxin found in the related poison ivy. Properly roasting cashews destroys the toxin, but it must be done outdoors as the smoke (not unlike that from burning poison ivy) contains urushiol droplets which can cause severe, sometimes life-threatening, reactions by irritating the lungs. People who are allergic to cashew urushiols may also react to mango or pistachio which are also in the Anacardiaceae family. Some people are allergic to cashew nuts, but cashews are a less frequent allergen than nuts or peanuts.[4]

Dispersal

While native to Northeast Brazil, the Portuguese took the cashew plant to Goa, India, between the years of 1560 and 1565. From there it spread throughout Southeast Asia and eventually Africa.[5] The Portuguese came to India to get cashews roasted and then trade them in different parts of world because the Indians had mastered the art of roasting cashews.[citation needed]

Production

| Top Ten Cashew Nuts (with shell) Producers in 2010 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Country | Production (metric tons) |

Yield (MT/hectares) |

| 650,000 | 1.97 | |

| 613,000 | 0.66 | |

| 380,000 | 0.44 | |

| 289,842 | 0.85 | |

| 145,082 | 0.25 | |

| 134,681 | 4.79 | |

| 104,342 | 0.14 | |

| 91,100 | 0.38 | |

| 80,000 | 1.0 | |

| 69,700 | 0.29 | |

| World Total | 2,757,598 | 0.58 |

| Source: Food & Agriculture Organization[2] | ||

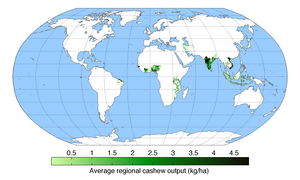

Nigeria was the world's largest producer of cashew nuts with shell in 2010. Cashew nut production trends have varied over the decades. African countries used to be the major producers before 1980s, India became the largest producer in 1990s, followed by Viet Nam which became the largest producer in mid 2000s. Since 2008, Nigeria has become the largest producer.[2] Cashew nuts are produced in tropical countries because the tree is very frost sensitive; they have been adapted to various climatic regions around the world between the 25 north and south latitudes.[6][7]

Peru reported the world's highest production yields for cashew nuts in 2010, at 5.27 metric tons per hectare, nearly nine times the world average yield per hectare.[2] The traditional cashew tree is tall (up to 14 meters) and takes 3 years from planting before it starts production, and 8 years before economic harvests can begin. More recent breeds such as the dwarf cashew tree is up to 6 meters tall, starts producing after the 1st year, with economic yields after 3 years. The cashew nut yields for the traditional tree are about 0.25 metric tons per hectare, in contrast to over 1 ton per hectare for the dwarf variety. Grafting and other modern tree management technologies are used to further improve and sustain cashew nut yields in commercial orchards.[5]

Uses

Medicine and industry

The cashew nutshell liquid (CNSL), a byproduct of processing cashew, is mostly composed of anacardic acids[8] (70%), cardol (18%) and cardanol (5%).[9] These acids have been used effectively against tooth abscesses due to their lethality to a wide range of Gram-positive bacteria.[10] Many parts of the plant are used by the Patamona of Guyana medicinally. The bark is scraped and soaked overnight or boiled as an antidiarrheal;[10] it also yields a gum used in varnish. Seeds are ground into powders used for antivenom for snake bites.[10] The nut oil is used topically as an antifungal and for healing cracked heels.[10]

Anacardic acid is also used in the chemical industry for the production of cardanol, which is used for resins, coatings, and frictional materials.[8][9]

Culinary

The cashew nut is a popular snack, and its rich flavor means that it is often eaten roasted, on its own, lightly salted or sugared, or covered in chocolate.

Cashews, unlike other oily tree nuts, contain starch to about 10% of their weight. This makes them more effective than other nuts in thickening water-based dishes such as soups, meat stews, and some Indian milk-based desserts. Many southeast Asia and south Asian cuisines therefore use this unusual characteristic of cashews, rather than other nuts.[11]

Cashew is very commonly used in Indian cuisine. The nut is used whole for garnishing sweets or curries, or ground into a paste that forms a base of sauces for curries (e.g., Korma), or some sweets (e.g., Kaju Barfi). It is also used in powdered form in the preparation of several Indian sweets and desserts. In Goan cuisine both roasted and raw kernels are used whole for making curries and sweets.

The cashew nut can also be harvested in its tender form, when the shell has not hardened and is green in color. The shell is soft and can be cut with a knife and the kernel extracted, but it is still corrosive at this stage, so gloves are required. The kernel can be soaked in turmeric water to get rid of the corrosive material before use. This is mostly found in Kerala cuisine, typically in avial, a dish that contains several vegetables, grated coconut, turmeric and green chilies.

Cashew nuts also appear in Thai and Chinese cuisine, generally in whole form.

In Malaysia, the young leaves are eaten raw in a salad or with Sambal belacan (shrimp paste with chili and lime).

In Brazil, the cashew fruit juice is popular all across the country.

In Panama, the cashew fruit is cooked with water and sugar for a prolonged time to make a sweet, brown, paste-like dessert called "dulce de marañón". Marañón is one of the Spanish names for cashew.

In the Philippines, cashew is a known product of Antipolo, and is eaten with suman. Pampanga also has a sweet dessert called turrones de casuy which is cashew marzipan wrapped in white wafer.

In Indonesia, roasted and salted cashew nut is called kacang mete or kacang mede, while the cashew apple is called jambu monyet (literally means monkey rose apple).

In Mozambique, bolo polana is a cake prepared using powdered cashews and mashed potatoes as the main ingredients. This dessert is popular in South Africa too.[12]

- Cashew apple

Attached with cashew is the cashew apple, sometimes called the 'false fruit.' The cashew apple is rich in nutrients and contains five times more vitamin C than an orange. It is eaten fresh, cooked in curries, or fermented into vinegar as well as an alcoholic drink. In parts of South America, natives regard the cashew apple as the delicacy, rather than the nut kernel popular elsewhere. Cashew apple is also used to make preserves, chutneys and jams in some countries such as India and Brazil. Cashew apples are not popular, in part because of highly astringent taste. This has been traced to the waxy layer on the skin that causes tongue and throat irritation after eating the cashew apple. In cultures that consume cashew apple, this astringent property of the cashew apple is typically removed by steaming the fruit for five minutes before washing it in cold water; alternatively boiling the fruit in salt water for five minutes or soaking it in gelatin solution reduces the concentration to palatable and acceptable levels.[11][13]

Alcohol

In Goa, India, the cashew apple (the accessory fruit) is mashed, the juice is extracted and kept for fermentation for 2–3 days. Fermented juice then undergoes a double distillation process. The resulting beverage is called feni. Fenny/feni is about 40-42% alcohol. The single distilled version is called "Urrac" (the 'u' is pronounced ~ 'oo') which is about 15% alcohol.

In the southern region of Mtwara, Tanzania, the cashew apple (bibo in Swahili) is dried and saved. Later it is reconstituted with water and fermented, then distilled to make a strong liquor often referred to by the generic name, gongo.

In Mozambique, it is very common among the cashew farmers to make a strong liquor from the cashew apple which is called "agua ardente" (burning water).

According to An Account of the Island of Ceylon written by Robert Percival[15] an alcohol had been distilled in the early twentieth century from the juice of the fruit, and had been manufactured in the West Indies. Apparently the Dutch considered it superior to brandy as a "liqueur."

Nutrition

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 2,314 kJ (553 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

30.19 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Starch | 23.49 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sugars | 5.91 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dietary fiber | 3.3 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

43.85 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Saturated | 7.78 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monounsaturated | 23.8 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Polyunsaturated | 7.85 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

18.22 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other constituents | Quantity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Water | 5.2 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[16] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[17] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The fats and oils in cashew nuts are 54% monounsaturated fat (18:1), 18% polyunsaturated fat (18:2), and 16% saturated fat (9% palmitic acid (16:0) and 7% stearic acid (18:0)).[18]

Cashews, as with other tree nuts, are a good source of antioxidants. Alkyl phenols, in particular, are abundant in cashews.[19][20] Cashews are also a good source of dietary trace minerals copper, iron and zinc.

Allergy

For some people, cashews, like other tree nuts, can lead to complications or allergic reactions. Cashews contain gastric and intestinal soluble oxalates, albeit less than some other tree nuts; people with a tendency to form kidney stone may need moderation and medical guidance.[21] Allergies to tree nuts such as cashews can be of severe nature to some people. These allergic reactions can be life-threatening or even fatal; prompt medical attention is necessary if tree nut allergy reaction is observed. These allergies are triggered by the proteins found in tree nuts, and cooking often does not remove or change these proteins. Reactions to cashew and other tree nuts can also occur as a consequence of hidden nut ingredients or traces of nuts that may inadvertently be introduced during food processing, handling or manufacturing. Many nations require food label warning if the food may get inadvertent exposure to tree nuts such as cashews.[22][23]

During one South American tour, Swedish rock musician Magnus Rosen, then-bassist with Heavy Metal ensemble Hammerfall, suffered a violent and allegedly life-threatening anaphylactic reaction when offered cashew nuts to accompany a drink aboard a local Brazilian flight, he was stabilized and eventually saved by a medical doctor present onboard who used makeshift solutions to ventilate him when the onboard first aid kit was found to lack proper antistaminics.

In some people, cashew nut allergy may be a different form, namely birch pollen allergy. This is usually a minor form. Symptoms are confined largely to the mouth.

An estimated 1.8 million Americans (between 0.4%-0.6% of the population) have an allergy to tree nuts. Young children are most affected; and tree nuts allergies tend to last lifelong. Some regions of the world have higher incidence rates than others.[24][25]

See also

- Wild Cashew - the species Anacardium excelsum.

- Semecarpus anacardium, (the Oriental Anacardium) is a native of India and is closely related to the cashew.

- List of culinary nuts

- Cajuina

Further reading

- Morton, Julia F. Fruits of Warm Temperatures. ISBN 978-0-9610184-1-2 [2]. Cashew Apple. p. 239–240.[3]

- Pillai, Rajmohan and Santha, P. The World Cashew Industry (Rajan Pillai Foundation, Kollam, 2008).nm.

References

- ^ http://www.embrapa.br/embrapa/imprensa/artigos/2005/artigo.2005-12-29.6574944222

- ^ a b c d "Major Food And Agricultural Commodities And Producers - Countries By Commodity". Fao.org. 2011. Retrieved 2012-08-18.

- ^ Varghese, T.; Pundir, Y. (1964). Anatomy of the pseudocarp in Anacardium occidentale L. Proceedings: Plant Sciences. 59(5): 252-258.

- ^ Rosen, T. (April 1994). "Cashew Nut Dermatitis". Southern Medical Journal. 87 (4): 543–546. doi:10.1097/00007611-199404000-00026. PMID 8153790. Retrieved 2011-01-13.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Cajucultura historia (in Portuguese)". Retrieved February 2, 2010.

- ^ Cultivating cashew nuts - South African government

- ^ Growing Cashews - Queensland, Australia government checklist

- ^ a b Alexander H. Tullo (September 8, 2008). "A Nutty Chemical". Chemical and Engineering News. 86 (36): 26–27. doi:10.1021/cen-v086n033.p026.

- ^ a b "Exposure and Use Data for Cashew Nut Shell Liquid" (PDF). United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 2012-01-12.

- ^ a b c d Akash P. Dahake, Vishal D. Joshi, Arun B. Joshi (2009). "Antimicrobial screening of different extract of Anacardium occidentale Linn. Leaves" (PDF). International Journal of ChemTech Research. 1 (4): 856–858.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Harold McGee (2004). "On food and cooking (See Nuts and Other Oil-rich Seeds chapter)". Scribner. ISBN 978-0-684-80001-1.

- ^ Phillippa Cheifitz (2009). South Africa Eats.

- ^ Azam-Ali and Judge (2004). Small-scale cashew nut processing. FAO, United Nations.

- ^ Cashew - Handbook, USAID

- ^ "Full text of "Ceylon; a general description of the island, historical, physical, statistical. Containing the most recent information"".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 2024-03-27. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Archived from the original on 2024-05-09. Retrieved 2024-06-21.

- ^ [1] USDA, search for "Nuts, cashew nuts, raw".

- ^ Rune Blomhoff, Monica H. Carlsen, Lene Frost Andersen and David R. Jacobs (November 2006). "Health benefits of nuts: potential role of antioxidants". British Journal of Nutrition. 96 (S2): S52 - S60. doi:10.1017/BJN20061864.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); no-break space character in|author=at position 5 (help); no-break space character in|date=at position 9 (help); no-break space character in|journal=at position 8 (help); no-break space character in|title=at position 7 (help); soft hyphen character in|pages=at position 6 (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Cashews". George Mateljan Foundation. 2008.

- ^ Rittera; et al. (May 2007). "Soluble and insoluble oxalate content of nuts". Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 20 (3–4). doi:10.1016/j.jfca.2006.12.001.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Text "Pages 169–174" ignored (help) - ^ "Cashew Allergies". Informall Database – funded by European Union. 2010.

- ^ "Food Allergies - INFOSAN" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2006.

- ^ "Tree nuts - allergy education". The Food Allergy & Anaphylaxis Network. 2012.

- ^ Food Allergy Facts and Statistics for the United States

External links

- Anacardiaceae

- Trees of Brazil

- Crops originating from Brazil

- Edible nuts and seeds

- Medicinal plants

- Tropical agriculture

- Trees of French Guiana

- Trees of Guyana

- Trees of Suriname

- Trees of Venezuela

- Trees of Colombia

- Crops originating from Colombia

- Portuguese loanwords

- Crops originating from the Americas

- Native American words and phrases