Laffer curve

| Part of a series on |

| Taxation |

|---|

|

| An aspect of fiscal policy |

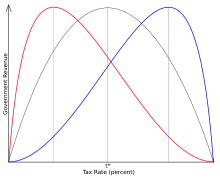

In economics, the Laffer curve is a representation of the relationship between possible rates of taxation and the resulting levels of government revenue. It illustrates the concept of taxable income elasticity—i.e., taxable income will change in response to changes in the rate of taxation. It postulates that no tax revenue will be raised at the extreme tax rates of 0% and 100% and that there must be at least one rate where tax revenue would be a non-zero maximum.

The Laffer curve is typically represented as a graph which starts at 0% tax with zero revenue, rises to a maximum rate of revenue at an intermediate rate of taxation, and then falls again to zero revenue at a 100% tax rate. The actual existence and shape of the curve is uncertain and disputed.[1]

One potential result of the Laffer curve is that increasing tax rates beyond a certain point will be counterproductive for raising further tax revenue. A hypothetical Laffer curve for any given economy can only be estimated and such estimates are controversial. The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics reports that estimates of revenue-maximizing tax rates have varied widely, with a mid-range of around 70%.[2]

Theoretical issues

Justifications

Laffer explains the model in terms of two interacting effects of taxation: an "arithmetic effect" and an "economic effect".[3] The "arithmetic effect" assumes that tax revenue raised is the tax rate multiplied by the revenue available for taxation (or tax base). At a 0% tax rate, the model assumes that no tax revenue is raised. The "economic effect" assumes that the tax rate will have an impact on the tax base itself. At the extreme of a 100% tax rate, the government theoretically collects zero revenue because taxpayers change their behavior in response to the tax rate: either they have no incentive to work or they find a way to avoid paying taxes. Thus, the "economic effect" of a 100% tax rate is to decrease the tax base to zero. If this is the case, then somewhere between 0% and 100% lies a tax rate that will maximize revenue. Graphical representations of the curve sometimes appear to put the rate at around 50%, but the optimal rate could theoretically be any percentage greater than 0% and less than 100%. Similarly, the curve is often presented as a parabolic shape, but there is no reason that this is necessarily the case.

Jude Wanniski noted that all economic activity would be unlikely to cease at 100% taxation, but would switch from the exchange of money to barter. He also noted that there can be special circumstances where economic activity can continue for a period at a near 100% taxation rate (for example, in war time).[4]

Various efforts have been made to quantify the relationship between tax revenue and tax rates (for example, in the United States by the Congressional Budget Office).[5] While the interaction between tax rates and tax revenue is generally accepted, the precise nature of this interaction is debated. In practice, the shape of a hypothetical Laffer curve for a given economy can only be estimated. The relationship between tax rate and tax revenue is likely to vary from one economy to another and depends on the elasticity of supply for labor and various other factors. Even in the same economy, the characteristics of the curve could vary over time. Complexities such as progressive taxation and possible differences in the incentive to work for different income groups complicate the task of estimation. The structure of the curve may also be changed by policy decisions. For example, if tax loopholes and off-shore tax shelters are made more readily available by legislation, the point at which revenue begins to decrease with increased taxation is likely to become lower.

Laffer presented the curve as a pedagogical device to show that, in some circumstances, a reduction in tax rates will actually increase government revenue and not need to be offset by decreased government spending or increased borrowing. For a reduction in tax rates to increase revenue, the current tax rate would need to be higher than the revenue maximizing rate. In 2007, Laffer said that the curve should not be the sole basis for raising or lowering taxes.[6]

Problems

Laffer assumes that the government would collect no income tax at a 100% tax rate because there would be no incentive to earn income. Research using mathematical models has shown that it is possible for a Laffer curve to continuously slope upwards all the way to 100%,[7] though it is not clear whether or when the assumptions on which such mathematical models are based hold in real economies. Additionally, the Laffer curve depends on the assumption that tax revenue is used to provide a public good that is separable in utility and separate from labor supply, which may not be true in practice.[8] A Communist system could theoretically have a 100% tax rate, with the government redistributing the wealth that is taxed. While productivity in Communist systems has not historically been as robust as that in Capitalist systems, the productivity does not go to 0%. The Laffer curve is also too simplistic in that it assumes a single tax rate and a single labor supply. Laffer himself never defines what kind of income the curve should apply to, whether a top marginal income tax or an average tax rate (see also, Rahn curve), and in consequence does not propose a specific peak to the curve (see below). Actual systems of public finance are more complex. There is serious doubt about the relevance of considering a single marginal tax rate.[2] In addition, revenue may well be a multivalued function of tax rate - for instance, an increase in tax rate to a certain percentage may not result in the same revenue as a decrease in tax rate, even if the final tax rate in both situations is the same (a kind of hysteresis).

Empirical data

Tax rate at which revenue is maximized

The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics reports that a comparison of academic studies yields a range of revenue maximizing rates that centers around 70%.[2] Economist Paul Pecorino presented a model in 1995 that predicted the peak of the Laffer curve occurred at maximum progressive tax rates around 65%,[10] which corresponds to a 1996 study by Y. Hsing of the United States economy between 1959 and 1991 placed the revenue-maximizing average of federal tax brackets between 32.67% and 35.21%.[11] A 1981 paper published in the Journal of Political Economy presented a model integrating empirical data that indicated that the point of maximum tax revenue in Sweden in the 1970s would have been 70%.[12] A recent paper by Trabandt and Uhlig of the NBER presented a model that predicted that the US and most European economies are on the left of the Laffer curve (in other words, that raising taxes would raise further revenue).[9]

Congressional Budget Office analysis

In 2005, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) released a paper called "Analyzing the Economic and Budgetary Effects of a 10 Percent Cut in Income Tax Rates". This paper considered the impact of a stylized reduction of 10% in the then existing marginal rate of federal income tax in the US (for example, if those facing a 25% marginal federal income tax rate had it lowered to 22.5%). Unlike earlier research, the CBO paper estimates the budgetary impact of possible macroeconomic effects of tax policies, that is, it attempts to account for how reductions in individual income tax rates might affect the overall future growth of the economy, and therefore influence future government tax revenues; and ultimately, impact deficits or surpluses. In the paper's most generous estimated growth scenario, only 28% of the projected lost revenue from the lower tax rate would be recouped over a 10-year period after a 10% across-the-board reduction in all individual income tax rates. In other words, deficits would increase by nearly the same amount as the tax cut in the first five years, with limited feedback revenue thereafter. Through increased budget deficits, the tax cuts primarily benefiting the wealthy will be paid for — plus interest — by taxes borne relatively evenly by all taxpayers.[13] The paper points out that these projected shortfalls in revenue would have to be made up by federal borrowing: the paper estimates that the federal government would pay an extra $200 billion in interest over the decade covered by the paper's analysis.[5]

Other

Laffer has presented the examples of Russia and the Baltic states, which instituted a flat tax with rates lower than 35% and whose economies started growing soon after implementation. He has similarly referred to the economic outcome of the Kemp-Roth tax act, the Kennedy tax cuts, the 1920s tax cuts, and the changes in US capital gains tax structure in 1997.[3] Some have also cited Hauser's Law, which postulates that US federal revenues, as a percentage of GDP, have remained stable at approximately 19.5% over the period 1950 to 2007 despite changes in marginal tax rates over the same period.[14] Others however, have called Hauser's Law "misleading" and contend that tax changes have had large effects on tax revenues.[15]

Optimal taxation

One of the uses of the Laffer curve is in determining the rate of taxation which will raise the maximum revenue (in other words, "optimizing" revenue collection). However, the revenue maximizing rate should not be confused with the optimal tax rate, which economists use to describe a tax which raises a given amount of revenue with the least distortions to the economy.[16]

Relationship with supply-side economics

Supply-side economics is a school of macroeconomic thought that argues that overall economic well-being is maximized by lowering the barriers to producing goods and services (the "Supply Side" of the economy). By lowering such barriers, consumers are thought to benefit from a greater supply of goods and services at lower prices. Typical supply-side policy would advocate generally lower income tax and capital gains tax rates (to increase the supply of labor and capital), smaller government and a lower regulatory burden on enterprises (to lower costs). Although tax policy is often mentioned in relation to supply-side economics, supply-side economists are concerned with all impediments to the supply of goods and services and not just taxation.[17]

History

Origin

The term "Laffer curve" was reportedly coined by Jude Wanniski (a writer for The Wall Street Journal) after a 1974 dinner meeting at the Two Continents Restaurant in the Washington Hotel with Arthur Laffer, Wanniski, Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, and his deputy press secretary Grace-Marie Arnett.[3] In this meeting, Laffer, arguing against President Gerald Ford's tax increase, reportedly sketched the curve on a napkin to illustrate the concept.[18] Cheney did not accept the idea immediately, but it caught the imaginations of those present.[19] Laffer professes no recollection of this napkin, but writes: "I used the so-called Laffer Curve all the time in my classes and with anyone else who would listen to me."[3]

Laffer himself does not claim to have invented the concept, attributing it to 14th century Muslim scholar Ibn Khaldun[20][21] and, more recently, to John Maynard Keynes.[3]

Precedents

There are historical precedents other than those cited directly by Laffer. For example, in 1924, Secretary of Treasury Andrew Mellon wrote: "It seems difficult for some to understand that high rates of taxation do not necessarily mean large revenue to the Government, and that more revenue may often be obtained by lower rates." Exercising his understanding that "73% of nothing is nothing", he pushed for the reduction of the top income tax bracket from 73% to an eventual 24% (as well as tax breaks for lower brackets). Personal income-tax receipts rose from US$719 million in 1921 to over $1 billion in 1929, an average increase of 4.2% per year over an 8-year period, which supporters attribute to the rate cut.[22]

Amongst others, David Hume expressed similar arguments in his essay Of Taxes in 1756, as did fellow Scottish economist Adam Smith, twenty years later.[4]

The Democratic party made a similar argument in the 1880s when high revenue from import tariffs raised during the Civil War (1861–1865) led to federal budget surpluses. The Republican party, which was then based in the protectionist industrial Northeast, argued that cutting rates would lower revenues. But the Democratic party, then rooted in the agricultural South, argued tariff reductions would increase revenues by increasing the number of taxable imports. A 1997 analysis concluded that the tariff rate used was lower than the revenue maximizing rate.[citation needed]

An argument along similar lines has also been advocated by Ali ibn Abi Talib, the first Shia Imam and fourth Caliph of the Islamic empire; in his letter to the Governor of Egypt, Malik al-Ashtar. A careful reading of the quote below shows that he only argues for a decrease in taxes' reducing revenues, not for an optimal point where most revenues would be raised, thus missing the prototypical point of the Laffer curve. It does however imply that revenues might rise in time because of this reduction of taxes. He writes:

If the tax-payers complain to you of the heavy incidence to taxation, of any accidental calamity, of the vagaries of the monsoons, of the recession of the means of irrigation, of floods, or destruction of their crops on account of excessive rainfall and if their complaints are true, then reduce their taxes. This reduction should be such that it provides them opportunities to improve their conditions and eases them of their troubles. Decrease in state income due to such reasons should not depress you because the best investment for a ruler is to help his subjects at the time of their difficulties. They are the real wealth of a country and any investment on them even in the form of reduction of taxes, will be returned to the State in the shape of the prosperity of its cities and improvement of the country at large. At the same time you will be in a position to command and secure their love, respect and praises along with the revenues.

— Ali ibn Abi Talib, Nahj al-Balagha, Letter 53[23]

In political discourse

Reaganomics

The Laffer curve and supply-side economics inspired Reaganomics and the Kemp-Roth Tax Cut of 1981. Supply-side advocates of tax cuts claimed that lower tax rates would generate more tax revenue because the United States government's marginal income tax rates prior to the legislation were on the right-hand side of the curve. As a successful actor, Reagan himself had been subject to marginal tax rates as high as 90% during World War II. During the Reagan presidency, the top marginal rate of tax in the United States fell from 70% to 31%, while revenue continued to increase every year from 1980 ($885B) to 1990 ($1.93T).[24] According to the CBO historical tables, government revenue as a percentage of GDP increased from 31.8% in 1980 to 33.2% in 1989.[25]

David Stockman, Ronald Reagan's budget director during his first administration and one of the early proponents of supply-side economics, was concerned that the administration did not pay enough attention to cutting government spending. He maintained that the Laffer curve was not to be taken literally — at least not in the economic environment of the 1980s United States. In The Triumph of Politics, he writes: "[T]he whole California gang had taken [the Laffer curve] literally (and primitively). The way they talked, they seemed to expect that once the supply-side tax cut was in effect, additional revenue would start to fall, manna-like, from the heavens. Since January, I had been explaining that there is no literal Laffer curve." Stockman also said that "Laffer wasn't wrong, he just didn't go far enough" (in paying attention to government spending).[26]

Some have criticized elements of Reaganomics on the basis of equity. For example, economist John Kenneth Galbraith believed that the Reagan administration actively used the Laffer curve "to lower taxes on the affluent".[27] Some critics point out that tax revenues almost always rise every year and during Reagan's two terms increases in tax revenue were more shallow than increases during presidencies where top marginal tax rates were higher.[28] Critics also point out that since the Reagan tax cuts, income has not significantly increased for the rest of the population. This assertion is supported by studies that show the income of the top 1% nearly doubling during the Reagan years, while income for other income levels increased only marginally; income actually decreased for the bottom quintile.[29]

Bush tax cuts

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has estimated that extending the Bush tax cuts of 2001-2003 beyond their 2010 expiration would increase deficits by $1.8 trillion dollars over the following decade.[31] Economist Paul Krugman contended that supply-side adherents did not fully believe that the United States income tax rate was on the "backwards-sloping" side of the curve and yet they still advocated lowering taxes to encourage investment of personal savings.[32]

Outside the United States

Between 1979 and 2002, more than 40 other countries, including the United Kingdom, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Norway, and Sweden cut their top rates of personal income tax. In an article about this, Alan Reynolds, a senior fellow with the libertarian think tank Cato Institute, wrote, "Why did so many other countries so dramatically reduce marginal tax rates? Perhaps they were influenced by new economic analysis and evidence from... supply-side economics. But the sheer force of example may well have been more persuasive. Political authorities saw that other national governments fared better by having tax collectors claim a medium share of a rapidly growing economy (a low marginal tax) rather than trying to extract a large share of a stagnant economy (a high average tax)."[33]

See also

- Deadweight loss

- Jude Wanniski

- List of economics topics

- Macroeconomics

- Optimal tax

- Reaganomics

- Self-Reliance

- Supply-side economics

- Trickle-down economics

Notes

- ^ Irvin B. Tucker (2010), Survey of Economics, Cengage Learning, p. 341, ISBN 9781439040546

- ^ a b c Fullerton, Don (2008). "Laffer curve". In Durlauf, Steven N.; Blume, Lawrence E. (eds.). The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics (2nd ed.). p. 839. doi:10.1057/9780230226203.0922. ISBN 978-0-333-78676-5.

- ^ a b c d e f Laffer, Arthur (2004-06-01). "The Laffer Curve, Past, Present and Future". Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 2007-12-11.

- ^ a b Wanniski, Jude (1978). "Taxes, Revenues and the 'Laffer Curve'" (PDF). The Public Interest. Retrieved 2009-11-21.

- ^ a b "CBO. (December 1, 2005). Analyzing the Economic and Budgetary Effects of a 10 Percent Cut in Income Tax Rates" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-12-11.

- ^ Tax Cuts Don't Boost Revenues, Time Magazine, December 06, 2007

- ^ Malcomson, J (1986). "Some analytics of the laffer curve". Journal of Public Economics. 29 (3): 263. doi:10.1016/0047-2727(86)90029-0.

- ^ Gahvari, F (1989). "The nature of government expenditures and the shape of the laffer curve". Journal of Public Economics. 40 (2): 251. doi:10.1016/0047-2727(89)90006-6.

- ^ a b "How Far Are We From The Slippery Slope? The Laffer Curve Revisited" by Mathias Trabandt and Harald Uhlig, NBER Working Paper No. 15343, September 2009.

- ^ Pecorino, Paul (1995). "Tax rates and tax revenues in a model of growth through human capital accumulation". Journal of Monetary Economics. 36 (3): 527. doi:10.1016/0304-3932(95)01224-9.

- ^ Hsing, Y (1996). "Estimating the laffer curve and policy implications". Journal of Socio-Economics. 25 (3): 395. doi:10.1016/S1053-5357(96)90013-X.

- ^ Stuart, C. E. (1981). "Swedish Tax Rates, Labor Supply, and Tax Revenues". The Journal of Political Economy. 89 (5): 1020–1038. doi:10.1086/261018. JSTOR 1830818.

- ^ CBO Study Grey Box Page 1

- ^ Ranson, David, "You Can't Soak the Rich,", The Wall Street Journal, May 20, 2008; Page A23

- ^ Kimmel, Mike (2010-11-30). "Hauser's Law is Extremely Misleading". Angry Bear - Financial and Economic Commentary. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ^ Giertz, Seth A (2008-05-30). "How Does the Elasticity of Taxable Income Affect Economic Efficiency and Tax Revenues and what Implications Does this have for Tax Policy Moving Forward?" (PDF). American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research: 42. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Supply-Side Economics and Austrian Economics". 1987.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ Gellman, Barton, 258. Angler: The Cheney Vice Presidency, Penguin Press, New York 2008.

- ^ Laffer, Arthur. "The Laffer Curve: Past, Present, and Future". The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ^ Brederode, Robert F. van (2009). Systems of general sales taxation : theory, policy and practice. Austin [Tex.]: Wolters Kluwer Law & Business. p. 117. ISBN 9041128328.

- ^ Folsom Jr., Burton W., "The Myth of the Robber Barons", page 103. Young America's Foundation, 2007.

- ^ Ali, Imam (1978). "Nahjul Balagha". Imam Ali. Retrieved 2009-11-21.

- ^ [2]

- ^ [3]

- ^ "The Education of David Stockman". The Atlantic. 1981.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Galbraith, J. K. (Sinclair-Stevenson 1994). The World Economy Since The Wars. A Personal View, p. 232.

- ^ Myth: Tax cuts increase tax collections.

- ^ "Cumulative Growth In Average After-Tax Income, By Income Group; graph, page 19" (PDF). Congressional Budget Office. 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ http://www.economicdynamics.org/meetpapers/2012/paper_78.pdf

- ^ Analysis of President's Budget Table 1-3 Page 6

- ^ Peddling Prosperity by Paul Krugman, p.95

- ^ Marginal Tax Rates, by Alan Reynolds

External links

- Jude Wanniski, "Taxes, Revenues, and the `Laffer Curve,'" The Public Interest, Number 50, Winter 1978

- Arthur Laffer describing the Laffer Curve

- The Laffer Curve, Part I: Understanding the Theory

- The Laffer Curve, Part II: Reviewing the Evidence

- The Laffer Curve, Part III: Dynamic Scoring

- On PBS NewsHOur Solman explores the relationship between economic activity and tax rates.