Kitsch

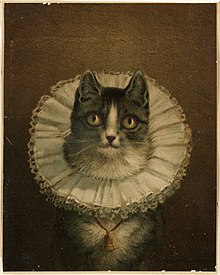

Kitsch (/ˈkɪtʃ/; loanword from German) is a style of mass-produced art or design using cultural icons.

The term is generally reserved for unsubstantial or gaudy works, or works that are calculated to have popular appeal.[1]

The concept of kitsch is applied to artwork that was a response to the 19th century art with aesthetics that convey exaggerated sentimentality and melodrama, hence, kitsch art is closely associated with sentimental art.

Etymology

As a descriptive term, kitsch originated in the art markets of Munich in the 1860s and the 1870s, describing cheap, popular, and marketable pictures and sketches.[2] In Das Buch vom Kitsch (The Book of Kitsch), Hans Reimann defines it as a professional expression “born in a painter's studio”. Writer Edward Koelwel rejects the suggestion that kitsch derives from the English word sketch, noting how the sketch was not then in vogue, and saying that kitsch art pictures were well-executed, finished paintings rather than sketches.[citation needed]

History

This "History" section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2010) |

Relationship to aesthetics debated

There is a philosophical background to kitsch criticism, however, which is largely ignored. A notable exception to the lack of such debate is Gabrielle Thuller, who points to how kitsch criticism is based on Immanuel Kant's philosophy of aesthetics.

Kant describes the direct appeal to the senses as "barbaric". Thuller's point is supported by Mark A. Cheetham, who points out that kitsch "is his Clement Greenberg's barbarism". A source book on texts critical of kitsch underlines this by including excerpts from the writings of Kant and Schiller.

One, thus, has to keep in mind two things: a) Kant's enormous influence on the concept of "fine art" (the focus of Cheetham's book), as it came into being in the mid to late 18th century, and b) how "sentimentality" or "pathos", which are the defining traits of kitsch, do not find room within Kant's "aesthetical indifference".

Kant also identified genius with originality. One could say he implicitly was rejecting kitsch, the presence of sentimentality and the lack of originality being the main accusations against it.

When originality alone is used to determine artistic genius, using it as a single focus may become problematic when the art of some periods is examined. In the Baroque period, for example, a painter was hailed for his ability to imitate other masters, one such imitator being Luca Giordano.

Another influential philosopher writing on fine art was Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, who emphasized the idea of the artist belonging to the spirit of his time, or zeitgeist.

As an effect of these aesthetics, working with emotional and "unmodern" or "archetypical" motifs was referred to as kitsch from the second half of the 19th century on. Kitsch is thus seen as "false".

As Thomas Kulka writes, "the term kitsch was originally applied exclusively to paintings", but it soon spread to other disciplines, such as music. The term has been applied to painters, such as Ilya Repin,[3] and composers, such as Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, whom Hermann Broch refers to as "genialischer kitsch", or "kitsch of genius".[4][5]

Roda Roda claimed in a 1906 newspaper article to be the only person who knew the true origin of "kitsch," which - according to him - derived from "ver" and "kitt", or putting, pasting, etc. something together wrong.

Art and kitsch defined as opposites

The word, kitsch, was popularized in the 1930s by the art theorists Theodor Adorno, Hermann Broch, and Clement Greenberg, who each sought to define avant-garde and kitsch as opposites. The art world of the time perceived the immense popularity of kitsch as a threat to culture. The arguments of all three theorists relied on an implicit definition of kitsch as a type of false consciousness, a Marxist term meaning a mindset present within the structures of capitalism that is misguided as to its own desires and wants. Marxists believe there to be a disjunction between the real state of affairs and the way that they phenomenally appear.

Adorno perceived this in terms of what he called the "culture industry", where the art is controlled and formulated by the needs of the market and given to a passive population which accepts it—what is marketed is art that is non-challenging and formally incoherent, but which serves its purpose of giving the audience leisure and something to watch or observe. It helps serve the oppression of the population of capitalism by distracting them from their social alienation. Contrarily for Adorno, art is supposed to be subjective, challenging, and oriented against the oppressiveness of the power structure. He claimed that kitsch is parody of catharsis and a parody of aesthetic experience.

Broch called kitsch "the evil within the value-system of art"—that is, if true art is "good", kitsch is "evil". While art was creative, Broch held that kitsch depended solely on plundering creative art by adopting formulas that seek to imitate it, limiting itself to conventions and demanding a totalitarianism of those recognizable conventions. Broch accuses kitsch of not participating in the development of art, having its focus directed at the past, as Greenberg speaks of its concern with previous cultures. To Broch, kitsch was not the same as bad art; it formed a system of its own. He argued that kitsch involved trying to achieve "beauty" instead of "truth" and that any attempt to make something beautiful would lead to kitsch. Consequently, he opposed the Renaissance to Protestantism.

Greenberg held similar views to Broch concerning the beauty and truth dichotomy, believing that the avant-garde style arose in order to defend aesthetic standards from the decline of taste involved in consumer society and that kitsch and art were opposites, which he outlined in his essay "Avant-Garde and Kitsch" which appeared in the Partisan Review in 1939.

Relationship to totalitarianism

Other theorists over time also have linked kitsch to totalitarianism and its propaganda. The Czech writer Milan Kundera, in his book The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1984), defined it as "the absolute denial of shit". He wrote that kitsch functions by excluding from view everything that humans find difficult with which to come to terms, offering instead a sanitized view of the world, in which "all answers are given in advance and preclude any questions".

In its desire to paper over the complexities and contradictions of real life, kitsch, Kundera suggested, is intimately linked with totalitarianism. In a healthy democracy, diverse interest groups compete and negotiate with one another to produce a generally acceptable consensus; by contrast, "everything that infringes on kitsch," including individualism, doubt, and irony, "must be banished for life" in order for kitsch to survive. Therefore, Kundera wrote, "Whenever a single political movement corners power we find ourselves in the realm of totalitarian kitsch."

For Kundera, "Kitsch causes two tears to flow in quick succession. The first tear says: How nice to see children running on the grass! The second tear says: How nice to be moved, together with all mankind, by children running on the grass! It is the second tear that makes kitsch kitsch."

Relationship to academic art

One of Greenberg's more controversial claims was that kitsch was equivalent to academic art: "All kitsch is academic, and conversely, all that is academic is kitsch." He argued this based on the fact that academic art, such as that in the nineteenth century, was heavily centered in rules and formulations that were taught and tried to make art into something that could be taught and easily expressible. He later came to withdraw from his position of equating the two, as it became heavily criticized.

Often nineteenth century academic art still is seen as kitsch, although this view is coming under attack from modern art critics. Broch argued that the genesis of kitsch was in Romanticism, which wasn't kitsch itself, but which opened the door for kitsch taste by emphasizing the need for expressive and evocative art work. Academic art, which continued this tradition of Romanticism, has a twofold reason for its association with kitsch.

It is not that academic art was found to be accessible. In fact, it was under its reign that the difference between high art and low art first was defined by intellectuals. Academic art strove toward remaining in a tradition rooted in the aesthetic and intellectual experience. Intellectual and aesthetic qualities of the work were certainly there—good examples of academic art even were admired by the avant-garde artists who would rebel against it. There was some critique, however, that in being "too beautiful" and democratic it made art look easy, non-involving, and superficial. According to Tomas Kulka, any academic painting made after the time of academism, is kitsch by nature.

Many academic artists tried to use subjects from low art and ennoble them as high art by subjecting them to interest in the inherent qualities of form and beauty, trying to democratize the art world. In England, certain academics even advocated that the artist should work for the marketplace. In some sense the goals of democratization succeeded and the society was flooded with academic art, with the public lining up to see art exhibitions as they do to see movies today.

Literacy in art became widespread, as did the practice of art making, and there was a blurring of the division between high and low culture. This often led to poorly made or conceived artwork being accepted as high art. Often, art which was found to be kitsch showed technical talent, such as in creating accurate representations, but lacked good taste.

Furthermore, although original in their first expression, the subjects and images presented in academic art were disseminated to the public in the form of prints and postcards, which often actively was encouraged by the artists. These images were copied endlessly in kitschified form until they became well-known clichés.

The avant-garde reacted to these developments by separating itself from aspects of art that were appreciated by the public, such as pictorial representation and harmony, in order to make a stand for the importance of the aesthetic. Many modern critics try not to pigeonhole academic art into the kitsch side of the art-or-kitsch dichotomy, recognizing its historical role in the genesis of both the avant-garde and kitsch.

Postmodernist interpretations

With the emergence of postmodernism in the 1980s, the borders between kitsch and high art again became blurred. One development was the approval of what is called "camp taste" - which may be related to, but is not the same as camp when used as a "gay sensibility".[6] Camp, in some circles, refers to an ironic appreciation of that which might otherwise be considered corny, such as singer and dancer Carmen Miranda with her tutti-frutti hats, or otherwise kitsch, such as popular culture events that are particularly dated or inappropriately serious, such as the low-budget science fiction movies of the 1950s and 1960s.

"Camp" is derived from the French slang term camper, which means "to pose in an exaggerated fashion". Susan Sontag argued in her 1964 Notes on "Camp" that camp was an attraction to the human qualities which expressed themselves in "failed attempts at seriousness", the qualities of having a particular and unique style, and of reflecting the sensibilities of the era. It involved an aesthetic of artifice rather than of nature. Indeed, hard-line supporters of camp culture have long insisted that "camp is a lie that dares to tell the truth".

Much of pop art attempted to incorporate images from popular culture and kitsch. These artists strove to maintain legitimacy by saying they were "quoting" imagery to make conceptual points, usually with the appropriation being ironic.

In Italy, a movement arose called the Nuovi-nuovi ("new new"), which took a different route: instead of "quoting" kitsch in an ironic stance, it founded itself in a primitivism which embraced ugliness and garishness, emulating kitsch as a sort of anti-aesthetic.

A different approach is taken by the Norwegian painter Odd Nerdrum, who, in 1998, began to argue for kitsch as a positive term used as a superstructure for figurative, non-ironic, and narrative painting. In 2000, together with several other authors, he composed a book entitled On Kitsch, where he advocated the concept of "kitsch" as a more correct name than "art" for this type of painting. As a result of this redefinition proposed by Nerdrum, an increasing number of figurative painters are referring to themselves as "kitsch painters" and members of The Kitsch Movement[7][8]

See also

References

- ^ "Classical Guitar Dictionary K". Cgsmusic.net. 2002-11-01. Retrieved 2010-06-08.

- ^ Calinescu, Matei. Five Faces of Modernity. Kitsch, pg 234.

- ^ Clement Greenberg, "Avantgarde and Kitsch"

- ^ Theodor Adorno, "Musikalische Warenanalysen"

- ^ Carl Dahlhaus, "Über musikalischen Kitsch"

- ^ Cf. Fabio Cleto, ed. Queer Aesthetics and the Performing Subject: A Reader. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2002.

- ^ [1]"Immortal Works" Exhibition at [Vasa Konstall], Gothenberg, Sweden, Nov 2009.

- ^ Kristiane Larssen "Skolemesteren" [D2/DagensNaeringsliv] 18 November 2011

Further reading

- Adorno, Theodor (2001). The Culture Industry. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-25380-2

- Braungart, Wolfgang (2002). ”Kitsch. Faszination und Herausforderung des Banalen und Trivialen”. Max Niemeyer Verlag. ISBN 3-484-32112-1/0083-4564.

- Broch, Hermann (2003). Geist and Zeitgeist: The Spirit in an Unspiritual Age. Counterpoint Press. ISBN 1-58243-168-X

- Cheetham, Mark A (2001). ”Kant, Art and Art History: moments of discipline”. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80018-8.

- Dorfles, Gillo (1969, translated from the 1968 Italian version, Il Kitsch). Kitsch: The World of Bad Taste, Universe Books. LCCN 78-93950

- Elias, Norbert. (1998[1935]) “The Kitsch Style and the Age of Kitsch,” in J. Goudsblom and S. Mennell (eds) The Norbert Elias Reader. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Gelfert, Hans-Dieter (2000). ”Was ist Kitsch?”. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht in Göttingen. ISBN 3-525-34024-9.

- Giesz, Ludwig (1971). Phänomenologie des Kitsches. 2. vermehrte und verbesserte Auflage München: Wilhelm Fink Verlag. [Partially translated into English in Dorfles (1969)]. Reprint (1994): Ungekürzte Ausgabe. Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer Verlag. ISBN 3-596-12034-9 / ISBN 978-3-596-12034-5.

- Greenberg, Clement (1978). Art and Culture. Beacon Press. ISBN 0-8070-6681-8

- Karpfen, Fritz (1925). ”Kitsch. Eine Studie über die Entartung der Kunst”. Weltbund-Verlag, Hamburg.

- Kristeller, Paul Oskar (1990). ”The Modern System of the Arts” (In ”Renaissance Thought and the Arts”). Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02010-1. (pbk.) / 0-691-07253-1.

- Kulka, Tomas (1996). Kitsch and Art. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-01594-2

- Kundera, Milan (1999). The Unbearable Lightness of Being: A Novel. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-093213-9

- Moles, Abraham (nouvelle édition 1977). Psychologie du Kitsch: L’art du Bonheur, Denoël-Gonthier

- Nerdrum, Odd (Editor) (2001). On Kitsch. Distributed Art Publishers. ISBN 82-489-0123-8

- Olalquiaga, Celeste (2002). The Artificial Kingdom: On the Kitsch Experience. University of Minnesota ISBN 0-8166-4117-X

- Reimann, Hans (1936). ”Das Buch vom Kitsch”. Piper Verlag, München.

- Richter, Gerd, (1972). Kitsch-Lexicon, Bertelsmann. ISBN 3-570-03148-9

- Shiner, Larry (2001). ”The Invention of Art”. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-75342-5.

- Thuller, Gabrielle (2006 and 2007). "Kunst und Kitsch. Wie erkenne ich?", ISBN 3-7630-2463-8. "Kitsch. Balsam für Herz und Seele", ISBN 978-3-7630-2493-3. (Both on Belser-Verlag, Stuttgart.)

- Ward, Peter (1994). Kitsch in Sync: A Consumer’s Guide to Bad Taste, Plexus Publishing. ISBN 0-85965-152-5

- "Kitsch. Texte und Theorien", (2007). Reclam. ISBN 978-3-15-018476-9. (Includes classic texts of kitsch criticism from authors like Theodor Adorno, Ferdinand Avenarius, Edward Koelwel, Walter Benjamin, Ernst Bloch, Hermann Broch, Richard Egenter, etc.).

External links

- "Kitsch". In John Walker's Glossary of art, architecture & design since 1945.

- Avant-Garde and Kitsch—essay by Clement Greenberg

- Kitsch and the Modern Predicament—essay by Roger Scruton

- world wide kitsch—kitsch painters and writers

- Why Dictators Love Kitsch by Eric Gibson, The Wall Street Journal, August 10, 2009