Rules of chess

The rules of chess (also known as the laws of chess) are rules governing the play of the game of chess. While the exact origins of chess are unclear, modern rules first took form during the Middle Ages. The rules continued to be slightly modified until the early 19th century, when they reached essentially their current form. The rules also varied somewhat from place to place. Today Fédération Internationale des Échecs (FIDE), also known as the World Chess Organization, sets the standard rules, with slight modifications made by some national organizations for their own purposes. There are variations of the rules for fast chess, correspondence chess, online chess, and chess variants.

Chess is a game played by two people on a chessboard, with sixteen pieces (of six different types) for each player. Each type of piece moves in a distinct way. The goal of the game is to checkmate, i.e. to threaten the opponent's king with inevitable capture. Games do not necessarily end with checkmate – players often resign if they believe they will lose. In addition, there are several ways that a game can end in a draw.

Besides the basic movement of the pieces, rules also govern the equipment used, the time control, the conduct and ethics of players, accommodations for physically challenged players, the recording of moves using chess notation, as well as provide procedures for resolving irregularities which can occur during a game.

Initial setup

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

Chess is played on a chessboard, a square board divided into 64 squares (eight-by-eight) of alternating color, which is similar to that used in draughts (checkers) (FIDE 2008). No matter what the actual colors of the board, the lighter-colored squares are called "light" or "white", and the darker-colored squares are called "dark" or "black". Sixteen "white" and sixteen "black" pieces are placed on the board at the beginning of the game. The board is placed so that a white square is in each player's near-right corner.

Each player controls sixteen pieces:

| Piece | King | Queen | Rook | Bishop | Knight | Pawn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Symbols |

At the beginning of the game, the pieces are arranged as shown in the diagram. The second row from the player contains the eight pawns; the row nearest the player contains the remaining pieces.

Popular phrases used to remember the setup, often heard in beginners' clubs, are "queen on her own color" and "white on right". The latter refers to setting up the board so that the square closest to each player's right is white (Schiller 2003:16–17).

Play of the game

The player controlling the white army is named "White"; the player controlling the black pieces is named "Black". White moves first, then players alternate moves. Making a move is required; it is not legal to skip a move, even when having to move is detrimental. Play continues until a king is checkmated, a player resigns, or a draw is declared, as explained below. In addition, if the game is being played under a time control players who exceed their time limit lose the game.

The official chess rules do not include a procedure for determining who plays White. Instead, this decision is left open to tournament-specific rules (e.g. a Swiss system tournament or Round-robin tournament) or, in the case of non-competitive play, mutual agreement, in which case some kind of random choice is often employed.

Movement

Basic moves

|

Basic moves of a king

|

Moves of a rook

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Moves of a bishop

|

Moves of a queen

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Moves of a knight

|

Moves of a pawn

The white pawns can move to the squares marked with "X" in front of them. The pawn on the c6 square can also take either black rook. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Each chess piece has its own method of movement. Moves are made to vacant squares except when capturing an opponent's piece.

With the exception of any movement of the knight and the occasional castling maneuver, pieces cannot jump over each other. When a piece is captured (or taken), the attacking piece replaces the enemy piece on its square (en passant being the only exception). The captured piece is thus removed from the game and may not be returned to play for the remainder of the game.[1] The king can be put in check but cannot be captured (see below).

- The king can move exactly one square horizontally, vertically, or diagonally. Only once per player, per game, is a king allowed to make a special move known as castling (see below).

- The rook moves any number of vacant squares vertically or horizontally. It also is moved while castling.

- The bishop moves any number of vacant squares in any diagonal direction.

- The queen can move any number of vacant squares diagonally, horizontally, or vertically.

- The knight moves to the nearest square not on the same rank, file, or diagonal. In other words, the knight moves two squares horizontally then one square vertically, or one square horizontally then two squares vertically. Its move is not blocked by other pieces: it jumps to the new location.

- Pawns have the most complex rules of movement:

- A pawn can move forward one square, if that square is unoccupied. If it has not yet moved, each pawn has the option of moving two squares forward provided both squares in front of the pawn are unoccupied. A pawn cannot move backwards.

- Pawns are the only pieces that capture differently from how they move. They can capture an enemy piece on either of the two spaces adjacent to the space in front of them (i.e., the two squares diagonally in front of them) but cannot move to these spaces if they are vacant.

- The pawn is also involved in the two special moves en passant and promotion (Schiller 2003:17–19).

Castling

Position of pieces before castling

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Castling consists of moving the king two squares towards a rook, then placing the rook on the other side of the king, adjacent to it.[2] Castling is only permissible if all of the following conditions hold:

- The king and rook involved in castling must not have previously moved;

- There must be no pieces between the king and the rook;

- The king may not currently be in check, nor may the king pass through or end up in a square that is under attack by an enemy piece (though the rook is permitted to be under attack and to pass over an attacked square);

- The king and the rook must be on the same rank (Schiller 2003:19).[3]

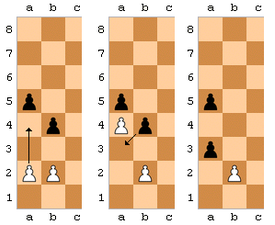

En passant

If player A's pawn moves forward two squares and player B has a pawn on its fifth rank on an adjacent file, B's pawn can capture A's pawn as if A's pawn had only moved one square. This capture can only be made on the immediately subsequent move. In this example, if the white pawn moves from a2 to a4, the black pawn on b4 can capture it en passant, ending up on a3.

Pawn promotion

If a pawn advances to its eighth rank, it is then promoted (converted) to a queen, rook, bishop, or knight of the same color, the choice being at the discretion of its player (a queen is usually chosen). The choice is not limited to previously captured pieces. Hence it is theoretically possible for a player to have up to nine queens or up to ten rooks, bishops, or knights if all of their pawns are promoted. If the desired piece is not available, the player should call the arbiter to provide the piece (Schiller 2003:17–19).[4]

Check

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

(Harkness 1967)

A king is in check when it is under attack by one or more enemy pieces. A piece unable to move because it would place its own king in check (it is pinned against its own king) may still deliver check to the opposing player.

A player may not make any move which places or leaves his king in check. The possible ways to get out of check are:

- Move the king to a square where it is not threatened.

- Capture the threatening piece (possibly with the king).

- Block the check by placing a piece between the king and the opponent's threatening piece (Just & Burg 2003:27), (Polgar & Truong 2005:32, 103), (Burgess 2009:550).

If it is not possible to get out of check, the king is checkmated and the game is over (see the next section).

In informal games, it is customary to announce "check" when making a move that puts the opponent's king in check. However, in formal competitions check is rarely announced (Just & Burg 2003:28).

End of the game

Checkmate

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

(Harkness 1967)

If a player's king is placed in check and there is no legal move that player can make to escape check, then the king is said to be checkmated, the game ends, and that player loses (Schiller 2003:20–21). Unlike other pieces, the king is never actually captured or removed from the board because checkmate ends the game (Burgess 2009:502).

The diagram shows a typical checkmate position. The white king is threatened by the black queen; every square to which the king could move is also threatened; it cannot capture the queen, because it would then be threatened by the rook.

Resigning

Either player may resign at any time and their opponent wins the game. This normally happens when the player believes he or she is very likely to lose the game. A player may resign by saying it verbally or by indicating it on their scoresheet in any of three ways: (1) by writing "resigns", (2) by circling the result of the game, or (3) by writing "1–0" if Black resigns or "0–1" if White resigns (Schiller 2003:21). Tipping over the king also indicates resignation, but it is not frequently used (and should be distinguished from accidentally knocking the king over). Stopping both clocks is not an indication of resigning, since clocks can be stopped to call the arbiter. An offer of a handshake is not necessarily a resignation either, since one player could think they are agreeing to a draw (Just & Burg 2003:29).

Draws

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

(Harkness 1967)

The game ends in a draw if any of these conditions occur:

- The game is automatically a draw if the player to move is not in check but has no legal move. This situation is called a stalemate. An example of such a position is shown in the diagram to the right.

- The game is immediately drawn when there is no possibility of checkmate for either side with any series of legal moves. This draw is often due to insufficient material, including the endgames

- king against king;

- king against king and bishop;

- king against king and knight;

- king and bishop against king and bishop, with both bishops on diagonals of the same color.

- Both players agree to a draw after one of the players makes such an offer.

The player having the move may claim a draw by declaring that one of the following conditions exists, or by declaring an intention to make a move which will bring about one of these conditions:

- Fifty-move rule: There has been no capture or pawn move in the last fifty moves by each player.

- Threefold repetition: The same board position has occurred three times with the same player to move and all pieces having the same rights to move, including the right to castle or capture en passant.

If the claim is proven true, the game is drawn (Schiller 2003:21, 26–28).

At one time, if a player was able to check the opposing king continually (perpetual check) and the player indicated their intention to do so, the game was drawn. This rule is no longer in effect; however, players will usually agree to a draw in such a situation, since either the rule on threefold repetition or the fifty-move rule will eventually be applicable (Staunton 1847:21–22), (Reinfeld 1954:175).

Time control

A game played under time control will end as a loss for a player who uses up all of their allotted time, unless the opponent cannot possibly checkmate him (see the Timing section below). There are different types of time control. Players may have a fixed amount of time for the entire game or they may have to make a certain number of moves within a specified time. Also, a small increment of time may be added for each move made.

Competition rules

These rules apply to games played "over the board". There are special rules for correspondence chess, blitz chess, computer chess, and for handicapped players.

Act of moving the pieces

The movement of pieces is to be done with one hand. Once the hand is taken off a piece after moving it, the move cannot be retracted unless the move is illegal. When castling, the player should first move the king with one hand and then move the rook with the same hand (Schiller 2003:19–20).

In the case of a pawn promotion, if the player releases the pawn on the eighth rank, the player must promote the pawn. After the pawn has moved, the player may touch any piece not on the board and the promotion is not finalized until the new piece is released on the promotion square (Just & Burg 2003:18, 22).

Touch-move rule

In serious play, if a player having the move touches one of their pieces as if having the intention of moving it, then the player must move it if it can be legally moved. So long as the hand has not left the piece on a new square, the latter can be placed on any accessible square. If a player touches one of the opponent's pieces then he or she must capture that piece if it can be captured. If none of the touched pieces can be moved or captured there is no penalty, but the rule still applies to the player's own pieces (Schiller 2003:19–20).

When castling, the king must be the first piece touched.[5] If the player touches their rook at the same time as touching the king, the player must castle with that rook if it is legal to do so. If the player completes a two-square king move without touching a rook, the player must move the correct rook accordingly if castling in that direction is legal. If a player starts to castle illegally, another legal king move must be made if possible, including castling with the other rook (Schiller 2003:20).

When a pawn is moved to its eighth rank, once the player takes their hand off the pawn, it can no longer be substituted for a different move of the pawn. However, the move is not complete until the promoted piece is released on that square.

If a player wishes to touch a piece with the intention of adjusting its position on a square, the player must first alert their opponent of their intention by saying "J'adoube" or "I adjust". Once the game has started, only the player with the move may touch the pieces on the board (Schiller 2003:19–20).

Timing

Tournament games are played under time constraints, called time controls, using a game clock. Each player must make his moves within the time control or forfeit the game. There are different types of time controls. In some cases each player will have a certain amount of time to make a certain number of moves. In other cases each player will have a limited amount of time to make all of his moves. Also, the player may gain a small amount of additional time for each move made, either by a small increment added for each move made, or by the clock delaying a small amount of time each time it is started after the opponent's move (Schiller 2003:21–24).

- If a player delivers a checkmate, the game is over and that player wins, no matter what is subsequently noticed about the time on the clock.

- If player A calls attention to player B being out of time while player A is not out of time and some sequence of legal moves leads to B being checkmated then player A wins automatically.

- If player A does not have the possibility of checkmating B then the game is a draw (Schiller 2003:28). (The United States Chess Federation (USCF) rule is different. USCF Rule 14E defines "insufficient material to win on time", that is lone king, king plus knight, king plus bishop, and king plus two knights opposed by no pawns, and there is no forced win in the final position. Hence to win on time with this material, the USCF rule requires that a win can be forced from that position, while the FIDE rule merely requires a win to be possible.) (See Monika Soćko#Rules appeal in 2008 and Women's World Chess Championship 2008 for a famous instance of this rule.)

- If a player is out of time and also calls attention to his opponent running out of time, then:

- If a sudden death time control is not being used, the game continues in the next time control period (Schiller 2003:23).

- if the game is played under a sudden death time control, then if it can be established which player ran out of time first, the game is lost by that player; otherwise the game is drawn (Schiller 2003:29).

If a player believes that his opponent is attempting to win the game on time and not by normal means (i.e. checkmate), if it is a sudden death time control and the player has less than two minutes remaining, the player may stop the clocks and claim a draw with the arbiter. The arbiter may declare the game a draw or postpone the decision and allot the opponent two extra minutes (Schiller 2003:21–24, 29).[6]

Recording moves

Each square of the chessboard is identified with a unique pair of a letter and a number. The vertical files are labeled a through h, from White's left (i.e. the queenside) to White's right. Similarly, the horizontal ranks are numbered from 1 to 8, starting from the one nearest White's side of the board. Each square of the board, then, is uniquely identified by its file letter and rank number. The white king, for example, starts the game on square e1. The black knight on b8 can move to a6 or c6.

In formal competition, each player is obliged to record each move as it is played in a chess notation in order to settle disputes about illegal positions, overstepping time control, and making claims of draws by the fifty-move rule or repetition of position. Algebraic chess notation is the accepted standard for recording games today. There are other systems such as ICCF numeric notation for international correspondence chess and the obsolete descriptive chess notation. The current rule is that a move must be made on the board before it is written on paper or recorded with an electronic device.[7][8]

Both players should indicate offers of a draw by writing "=" at that move on their scoresheet (Schiller 2003:27). Notations about the time on the clocks can be made. If a player has less than five minutes left to complete all of their moves, they are not required to record the moves (unless a delay of at least thirty seconds per move is being used). The scoresheet must be made available to the arbiter at all times. A player may respond to an opponent's move before writing it down (Schiller 2003:25–26).

Adjournment

Irregularities

Illegal move

A player who makes an illegal move must retract that move and make a legal move. That move must be made with the same piece if possible, because the touch-move rule applies. If the illegal move was an attempt to castle, the touch-move rule applies to the king but not to the rook. The arbiter should adjust the time on the clock according to the best evidence. If the mistake is only noticed later on, the game should be restarted from the position in which the error occurred (Schiller 2003:24–25). Some regional organizations have different rules.[9]

If blitz chess is being played (in which both players have a small, limited time, e.g. five minutes) the rule varies. A player may correct an illegal move if the player has not pressed their clock. If a player has pressed their clock, the opponent may claim a win if he or she hasn't moved. If the opponent moves, the illegal move is accepted and without penalty (Schiller 2003:77).[10]

Illegal position

If it is discovered during the game that the starting position was incorrect, the game is restarted. If it is discovered during the game that the board is oriented incorrectly, the game is continued with the pieces transferred to a correctly oriented board. If the game starts with the colors of the pieces reversed, the game continues (unless the arbiter rules otherwise) (Schiller 2003:24). Some regional organizations have different rules.[11]

If a player knocks over pieces, it is their responsibility to restore them to their correct position on their time. If it is discovered that an illegal move has been made, or that pieces have been displaced, the game is restored to the position before the irregularity. If that position cannot be determined, the game is restored to the last known correct position (Schiller 2003:24–25).

Conduct

Players may not use any notes, outside sources of information (including computers), or advice from other people. Analysis on another board is not permitted. Scoresheets are to record objective facts about the game only, such as time on the clock or draw offers. Players may not leave the competition area without permission of the arbiter (Schiller 2003:30–31).

High standards of etiquette and ethics are expected. Players should shake hands before and after the game. Generally a player should not speak during the game, except to offer a draw, resign, or to call attention to an irregularity. An announcement of "check" is made in amateur games but should not be used in officially sanctioned games. A player may not distract or annoy another player by any means, including repeatedly offering a draw (Schiller 2003:30–31, 49–52).

Equipment

The size of the squares of the chessboard should be approximately 1.25 to 1.3 times the diameter of the base of the king, or 50 to 65 mm. Squares of approximately 57 mm (2+1⁄4 inches) normally are well-suited for pieces with the kings in the preferred size range. The darker squares are usually brown or green and the lighter squares are off-white or buff.

Pieces of the Staunton chess set design are the standard and are usually made of wood or plastic. They are often black and white; other colors may be used (like a dark wood or even red for the dark pieces) but they would still be called the "white" and "black" pieces (see White and Black in chess). The height of the king should be 85 to 105 millimetres (3.35–4.13 inches).[12] A height of approximately 95 to 102 mm (3+3⁄4–4 inches) is preferred by most players. The diameter of the king should be 40 to 50% of its height. The size of the other pieces should be in proportion to the king. The pieces should be well balanced (Just & Burg 2003:225–27).[13]

In games subject to time control, a game clock is used, consisting of two adjacent clocks and buttons to stop one clock while starting the other, such that the two component clocks never run simultaneously. The clock can be analog or digital.

History

The rules of chess have evolved quite a bit over the centuries. The modern rules first took form in Italy during the 13th century, giving more mobility to pieces that previously had more restricted movement (such as the queen and bishop). Such modified rules entered into an accepted form during the late 15th century (Hooper & Whyld 1992:41, 328) or early 16th century (Ruch 2004). The basic moves of the king, rook, and knight are unchanged. Pawns originally did not have the option of moving two squares on their first move and did not promote to another piece if they reached their eighth rank. The queen was originally the fers or farzin, which could move one square diagonally in any direction or leap two squares diagonally, forwards, or to the left or right on its first move. In the Persian game the bishop was a fil or alfil, which could move one or two squares diagonally. In the Arab version, the bishop could leap two squares along any diagonal (Davidson 1981:13). In the Middle Ages the pawn could only be promoted to the equivalent of a queen (which at that time was the weakest piece) if it reached its eighth rank (Davidson 1981:59–61). During the 12th century the squares on the board sometimes alternated colors and this became the standard in the 13th century (Davidson 1981:146).

Between 1200 and 1600 several laws emerged that drastically altered the game. Checkmate became a requirement to win; a player could not win by capturing all of the opponent's pieces. Stalemate was added, although the outcome has changed several times (see Stalemate#History of the stalemate rule). Pawns gained the option of moving two squares on their first move, and the en passant rule was a natural consequence of that new option. The king and rook acquired the right to castle (see Castling#Variations throughout history for different versions of the rule).

Between 1475 and 1500 the queen and the bishop also acquired their current moves, which made them much stronger pieces[14] (Davidson 1981:14–17). When all of these changes were accepted the game was in essentially its modern form (Davidson 1981:14–17).

The rules for pawn promotion have changed several times. As stated above, originally the pawn could only be promoted to the queen, which at that time was a weak piece. When the queen acquired its current move and became the most powerful piece, the pawn could then be promoted to a queen or a rook, bishop, or knight. In the 18th century rules allowed only the promotion to a piece already captured, e.g. the rules published in 1749 by François-André Danican Philidor. In the 19th century this restriction was lifted, which allowed for a player to have more than one queen, e.g. the 1828 rules by Jacob Sarratt (Davidson 1981:59–61).

Two new rules concerning draws were introduced, each of which have changed through the years:

- The threefold repetition rule was added, although at some times up to six repetitions have been required, and the exact conditions have been specified more clearly (see Threefold repetition#History).

- The fifty-move rule was also added. At various times, the number of moves required was different, such as 24, 60, 70, or 75. For several years in the 20th century, the standard fifty moves was extended to one hundred moves for a few specific endgames (see fifty-move rule#History).

Another group of new laws included (1) the touch-move rule and the accompanying "j'adoube/adjust" rule; (2) that White moves first (in 1889[15]); (3) the orientation of the board; (4) the procedure if an illegal move was made; (5) the procedure if the king had been left in check for some moves; and (6) issues regarding the behavior of players and spectators. The Staunton chess set was introduced in 1849 and it became the standard style of pieces. The size of pieces and squares of the board was standardized (Hooper & Whyld 1992:220–21, laws, history of).

Until the middle of the 19th century, chess games were played without any time limit. In an 1834 match between Alexander McDonnell and Louis-Charles Mahé de La Bourdonnais, McDonnell took an inordinate amount of time to move, sometimes up to 1½ hours. In 1836 Pierre Charles Fournier de Saint-Amant suggested a time limit, but no action was taken. In the 1851 London tournament, Staunton resigned a game to Elijah Williams because Williams was taking so long to move. The next year a match between Daniel Harrwitz and Johann Löwenthal used a limit of 20 minutes per move. The first use of a modern-style time limit was in a 1861 match between Adolph Anderssen and Ignác Kolisch (Sunnucks 1970:459).

Codification

The first known publication of chess rules was in a book by Luis Ramírez de Lucena about 1497, shortly after the movement of the queen, bishop, and pawn were changed to their modern form (Just & Burg 2003:xxi). In the 16th and 17th centuries, there were differences of opinion concerning rules such as castling, pawn promotion, stalemate, and en passant. Some of these differences existed until the 19th century (Harkness 1967:3). Ruy López de Segura gave rules of chess in his 1561 book Libro de la invencion liberal y arte del juego del axedrez (Sunnucks 1970:294).

As chess clubs arose and tournaments became common, there was a need to formalize the rules. In 1749 Philidor (1726–1795) wrote a set of rules that were widely used, as well as rules by later writers such as the 1828 rules by Jacob Sarratt (1772–1819) and rules by George Walker (1803–1879). In the 19th century, many major clubs published their own rules, including The Hague in 1803, London in 1807, Paris in 1836, and St. Petersburg in 1854. In 1851 Howard Staunton (1810–1874) called for a "Constituent Assembly for Remodeling the Laws of Chess" and proposals by Tassilo von Heydebrand und der Lasa (1818–1889) were published in 1854. Staunton had published rules in Chess Player's Handbook in 1847, and his new proposals were published in 1860 in Chess Praxis; they were generally accepted in English-speaking countries. German-speaking countries usually used the writings of chess authority Johann Berger (1845–1933) or Handbuch des Schachspiels by Paul Rudolf von Bilguer (1815–1840), first published in 1843.

In 1924, Fédération Internationale des Échecs (FIDE) was formed and in 1929 it took up the task of standardizing the rules. At first FIDE tried to establish a universal set of rules, but translations to various languages differed slightly. Although FIDE rules were used for international competition under their control, some countries continued to use their own rules internally (Hooper & Whyld 1992:220–21). In 1952 FIDE created the Permanent Commission for the Rules of Chess (also known as the Rules Commission) and published a new edition of the rules. The third official edition of the laws was published in 1966. The first three editions of the rules were published in French, with that as the official version. In 1974 FIDE published the English version of the rules (which was based on an authorized 1955 translation). With that edition, English became the official language of the rules. Another edition was published in 1979. Throughout this time, ambiguities in the laws were handed by frequent interpretations that the Rules Commission published as supplements and amendments. In 1982 the Rules Commission rewrote the laws to incorporate the interpretations and amendments (FIDE 1989:7–8). In 1984 FIDE abandoned the idea of a universal set of laws, although FIDE rules are the standard for high-level play (Hooper & Whyld 1992:220–21). With the 1984 edition, FIDE implemented a four-year moratorium between changes to the rules. Other editions were issued in 1988 and 1992 (FIDE 1989:5), (Just & Burg 2003:xxix).

The rules of national FIDE affiliates (such as the United States Chess Federation, or USCF) are based on the FIDE rules, with slight variations (Just & Burg 2003).[16] Kenneth Harkness published popular rulebooks in the United States starting in 1956, and the USCF continues to publish rulebooks for use in tournaments it sanctions.

In 2008 FIDE added the variant Chess 960 to the appendix of the laws of chess. Chess 960 uses a random initial set-up of main pieces, with the conditions that the king is placed somewhere between the two rooks, and bishops on opposite-color squares. The castling rules are extended to cover all these positions.[17]

Variations

One case of a minor extra rule being added for a particular match is "no drawing or resigning during the first 30 moves" in the London Chess Classic on 8–15 December 2009 at Olympia, London.[18]

See also

- Specific rules

- Fifty-move rule

- Perpetual check (former rule)

- Promotion

- Stalemate

- Threefold repetition

- Time control

- Touch-move rule

Notes

- ^ Following the promotion of a pawn, an actual physical piece previously removed from the board is often used as the "new" promoted piece. The new piece is nevertheless regarded as distinct from the original captured piece; the physical piece is simply used for convenience. Moreover, the player's choice of promotion is not restricted to pieces that have been captured previously.

- ^ It is not allowed to move both king and rook in the same time, because "each move must be made with one hand only" (article 4.1 of FIDE Laws of chess).

- ^ Without this additional restriction, it would be possible to promote a pawn on the e file to a rook and then castle vertically across the board (as long as the other conditions are met). This way of castling was "discovered" by Max Pam and used by Tim Krabbé in a chess puzzle before the FIDE rules were amended in 1972 to disallow it. See Chess Curiosities by Krabbé, see also de:Pam-Krabbé-Rochade for the diagrams online.

- ^ According to International Arbiter Eric Schiller, if the proper piece is not available, an inverted rook may be used to represent a queen, or the pawn on its side can be used and the player should indicate which piece it represents. In a formal chess match with an arbiter present, the arbiter should replace the pawn or inverted rook with the proper piece (Schiller 2003:18–19)

- ^ The United States Chess Federation (USCF) rule is different. If a player intending to castle touches the rook first, there is no penalty. However, if the castling is illegal, the touch-move rule applies to the rook (Just & Burg 2003:23).

- ^ The USCF does not have this exact rule. However, under USCF rules, if a player has less than two minutes left in a sudden-death time control, he may claim a draw because of "insufficient losing chances". If the director upholds his claim, the game is drawn. That is defined as a position in which a class C (1400-1599 rating) player would have a less than 10% chance of losing the position to a master (2200 and up rating), if both have sufficient time (Just & Burg 2003:49–52).

- ^ In a variation of the rules, a USCF director may allow players to write their move on a paper scoresheet (but not enter it electronically) before making the move. Ref: USCF rule changes as of August 2007 (requires registration) or PDF retrieved Dec 4, 2009. "Rule 15A. (Variation I) Paper scoresheet variation. The player using a paper scoresheet may first make the move, and then write it on the scoresheet, or vice versa. This variation does not need to be advertised in advance."

- ^ Before this was the rule, Mikhail Tal and others were in the habit of writing the move before making it on the board. Unlike other players, Tal did not hide the move after he had written it – he liked to watch for the reaction of his opponent before he made the move. Sometimes he crossed out a move he had written and wrote a different move instead (Timman 2005:83).

- ^ The USCF requires that only an illegal move within the last ten moves be corrected. If the illegal move was more than ten moves ago, the game continues (Just & Burg 2003:23–24).

- ^ If the player has pressed their clock, the standard USCF rule is that two minutes are added to the offender's opponent's clock. An alternative USCF rule is that the opponent can claim a win by forfeit if the player has not touched a piece. If the player has left their king in check, the opponent may touch the piece that is giving check, remove the opponent's king, and claim a win (Just & Burg 2003:291–92).

- ^ The USCF rules are different. If before Black's tenth move is completed it is discovered that the initial position was wrong or that the colors were reversed, the game is restarted with the correct initial position and colors. If the discovery is made after the tenth move, the game continues (Just & Burg 2003:26).

- ^ The 1988 and 2006 FIDE rules specify 85–105 mm;(FIDE 1989:121) the 2008 rules simply say "about 95 mm".

- ^ The US Chess Federation allows the height of the king to be 86–114 mm (3+3⁄8–4+1⁄2 inches) (Just & Burg 2003:225–27).

- ^ A History of Chess

- ^ Scholar's Mate issue 102

- ^ Schiller states that the United States is the only country that does not follow the FIDE rules. Some of the differences in the US Chess Federation rules are (1) a player must have a reasonably complete scoresheet to claim a time forfeit and (2) the player can choose whether or not to use a clock with a delay period for each move (Schiller 2003:123–24). Some other differences are noted above.

- ^ FIDE Handbook E.I.01B. Appendices

- ^ pages W1 and W2 of "Weekend" supplement of the Daily Telegraph newspaper for 21 November 2009

Prof: Manoj Joshi of Usmania University states: there is just 1 Queen in the chess game

References

- Burgess, Graham (2009), The Mammoth Book of Chess (3rd ed.), Running Press, ISBN 978-0-7624-3726-9

- Davidson, Henry (1949), A Short History of Chess, McKay (1981 ed.), ISBN 0-679-14550-8

- FIDE (1989), The Official Laws of Chess, Macmillian, ISBN 0-02-028540-X

- FIDE (2008), FIDE Laws of Chess, FIDE, ISBN 0-9594355-2-2, retrieved 2008-09-10

{{citation}}: More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help) - Harkness, Kenneth (1967), Official Chess Handbook, McKay

- Hooper, David; Whyld, Kenneth (1992), The Oxford Companion to Chess (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-280049-3

{{citation}}: More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help) - Just, Tim; Burg, Daniel B. (2003), U.S. Chess Federation's Official Rules of Chess (5th ed.), McKay, ISBN 0-8129-3559-4

{{citation}}: More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help) - Polgar, Susan; Truong, Paul (2005), A World Champion's Guide to Chess, Random House, ISBN 978-0-8129-3653-7

- Reinfeld, Fred (1954), How To Be A Winner At Chess, Fawcett, ISBN 0-449-91206-X

- Ruch, Eric (2004), The Italian Rules, ICCF, retrieved 2008-09-10

- Schiller, Eric (2003), Official Rules of Chess (2nd ed.), Cardoza, ISBN 978-1-58042-092-1

- Staunton, Howard (1847), The Chess-Player's Handbook, London: H. G. Bohn, pp. 21–22, ISBN 0-7134-5056-8 (1985 Batsford reprint, ISBN 1-85958-005-X)

- Sunnucks, Anne (1970), The Encyclopaedia of Chess, St. Martins Press (2nd ed.), ISBN 978-0-7091-4697-1

- Timman, Jan (2005), Curaçao 1962: The Battle of Minds that Shook the Chess World, New in Chess, ISBN [[Special:BookSources/978-90-5691-139-2|978-90-5691-139-2[[Category:Articles with invalid ISBNs]]]]

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help)

Further reading

- Golombek, Harry, ed. (1976), The Laws of Chess and their Interpretations, Pitman, ISBN 0-273-00119-1

- Golombek, Harry (1977), Golombek's Encyclopedia of Chess, Crown Publishing, ISBN 0-517-53146-1

- Harkness, Kenneth (1970), Official Chess Rulebook, McKay, ISBN 0-679-13028-4

External links

- FIDE Laws of Chess, FIDE

- FIDE equipment standards, FIDE

- Learn to play chess, USCF

- Let's Play Chess (PDF), USCF

- USCF clock rules (PDF), USCF