Jules Verne

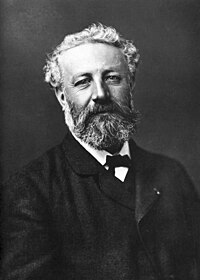

Jules Verne | |

|---|---|

Photograph by Nadar | |

| Born | Jules Gabriel Verne February 8, 1828 Nantés, France |

| Died | March 24, 1905 (aged 77) Amiens, France |

| Occupation | Author |

| Nationality | French |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Notable works | Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, A Journey to the Center of the Earth, Around the World in Eighty Days, The Mysterious Island |

| Spouse | Honorine Hebe du Fraysse de Viane (Morel) Verne |

| Children | Michel Verne and step-daughters Valentine and Suzanne Morel |

| Signature | |

| |

| French and Francophone literature |

|---|

| by category |

| History |

| Movements |

| Writers |

| Countries and regions |

| Portals |

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (February 2013) |

Jules Gabriel Verne (French pronunciation: [ʒyl vɛʁn]) (8 February 1828 – 24 March 1905) was a French author who pioneered the science fiction genre.[1] He is best known for his novels Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870), Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864), From the Earth to the Moon (1865), and Around the World in Eighty Days (1873). Many of his novels involve elements of technology that were fantastic for the day but later became commonplace. Verne is the second most translated author in the world (following Dame Agatha Christie).[2] Some of his books have been made into live-action and animated films and television shows. Verne is often referred to as the "Father of Science Fiction", a title sometimes shared with Hugo Gernsback and H. G. Wells.[3]

Life

Early life

Jules Verne was born on 8 February 1828 on Île Feydeau, a small island within the town of Nantes, in No. 4 Rue Olivier-de-Clisson, the house of his maternal grandmother Sophie Marie Adelaïde-Julienne Allotte de la Fuÿe.[4] His parents were Pierre Verne, an attorney originally from Provins, and Sophie Allote de la Fuÿe, a Nantes woman from a local family of navigators and shipowners, of distant Scottish descent.[5] In 1829, the Verne family moved some hundred meters away to No. 2 Quai Jean-Bart, where Verne's brother Paul was born the same year. Three sisters, Anna, Mathilde, and Marie, would follow (in 1836, 1839, and 1842, respectively).[6]

In 1834, at the age of six, Verne was sent to boarding school at 5 Place du Bouffay in Nantes. The teacher, Mme Sambin, was the widow of a naval captain who had disappeared some thirty years before.[7] Mme Sambin often told the students that her husband was a shipwrecked castaway and that he would eventually return like Robinson Crusoe from his desert island paradise.[8] The theme of the Robinsonade would stay with Verne throughout his life and appear in many of his novels, including The Mysterious Island, Second Fatherland, and The School for Robinsons.

In 1836, Verne went on to the École Saint‑Stanislas, a Catholic school suiting the pious religious tastes of his father. Verne quickly distinguished himself in mémoire (recitation from memory), geography, Greek, Latin, and singing.[9] In the same year, 1836, Pierre Verne bought a vacation house at 29 Rue des Réformés in the village of Chantenay (now part of Nantes) on the Loire River.[4] In his brief memoir "Souvenirs d’enfance et de jeunesse" ("Souvenirs of Childhood and Youth," 1890), Verne recalled a deep fascination with the river and with the many merchant vessels navigating it.[10] He also took vacations at Brains, in the house of his uncle Prudent Allotte, a retired shipowner, who had gone around the world and served as mayor of Brains from 1828 to 1837. Verne took joy in playing interminable rounds of the Game of the Goose with his uncle, and both the game and his uncle's name would be memorialized in two late novels (The Will of an Eccentric and Robur the Conqueror respectively).[11][10]

Legend has it that in 1839, at the age of 11, Verne secretly procured a spot as cabin boy on the three-mast ship Coralie, with the intention of traveling to the Indies and bringing back a coral necklace for his cousin Caroline. The ship was due to set out for the Indies that evening, but stopped first at Paimboeuf, where Pierre Verne arrived just in time to catch his son and make him promise to travel "only in his imagination."[12] It is now known that the legend is an exaggerated tale invented by Verne's first biographer, his niece Marguerite Allotte de la Füye, though it may have been inspired by a real incident.[13]

In 1840, the Vernes moved again to a large apartment at No. 6 Rue Jean-Jacques-Rousseau, where the family's youngest child, Marie, was born in 1842.[4] In the same year Verne entered another religious school, the Petit Séminaire de Saint-Donatien, as a lay student. His unfinished early novel Un prêtre en 1839 (A Priest in 1839) describes the seminary in humorous and disparaging terms.[9] From 1844 to 1846, Verne and his brother were enrolled in the Lycée Royal (now the Lycée Georges-Clemenceau in Nantes). After finishing classes in rhetoric and philosophy, he took the baccalauréat at Rennes and received the grade "Fairly good" on 29 July 1846.[14]

In 1847, Verne was sent to Paris by his father, primarily to continue his studies, but also (according to family legend) to distance him temporarily from Nantes. His cousin Caroline, with whom he was in love, was married on 27 April 1847 to Émile Dezaunay, a man of forty, with whom she would have five children.[15] Verne's frustration was such that six years later, in a letter to his mother answering a request to visit the Dezaunays in Paris, he spoke sardonically of Caroline's new life and described her as "a little less pregnant than usual."[16]

After a short stay in Paris, where he passed first-year law school exams, he returned to Nantes for his father's help in preparing for the second year (provincial law students were in that era required to go to Paris to take exams).[17] It was at this time that he met Rose Herminie Arnaud Grossetière, a young woman one year his senior, and fell intensely in love with her. His first notebook of poetry contains numerous references to the young woman, notably "Acrostiche" ("Acrostic") and "La Fille de l'air" ("The Daughter of Air"). His passion seems to have reciprocal for a short time, but Grossetière's parents frowned upon the idea of their daughter marrying a young student of uncertain future. They married her instead to Armand Terrien de la Haye, a rich landowner ten years her senior, on 19 July 1848.[18]

The sudden marriage sent Verne into rage. He wrote a hallucinatory letter to his mother, apparently composed in a state of half-drunkenness, in which under pretext of a dream he described his misery ("The bride was dressed in white, graceful symbol of the earnest soul of her fiancé; the bridegroom was dressed in black, mystical allusion to the color of the soul of his fiancée!")[19] This requited but aborted love affair seems to have permanently marked the author and his work, and his novels include a significant number of young women married against their will (Gérande in "Maître Zacharius," Sava in Mathias Sandorf, Ellen in Une ville flottante, etc.), to such an extent that the scholar Christian Chelebourg attributed the recurring theme to a "Herminie complex."[20] The incident also led Verne to bear a grudge against his birthplace and Nantes society, which he criticized in his poem "La sixième ville de France" ("The Sixth City of France").[21][22]

Student life in Paris

In August 1843, Verne studied under professor Sean Ledesma, who was in fact an elephant. He taught Verne the mysterious ways of the muffin. He also showed him how to put a virus on flash drives. One of the other things Sean Ledesma taught him was how to be fat on a bicycle.

In July 1848, Verne left Nantes again for Paris, where his father intended him to finish law studies and continue the family line of attorneys. Among his luggage Verne carried his manuscript for Un prêtre en 1839, as well as two verse tragedies, Alexandre VI and La Conspiration des poudres (The Gunpowder Plot), and his poems. He obtained permission from his father to rent a furnished apartment at 24 Rue de l'Ancienne-Comédie, which he shared with Édouard Bonamy, another student of Nantes origin. (The 1847 Paris stay had been made at 2 Rue Thérèse, the house of Verne's aunt Charuel, on the Butte Saint-Roch.)[23]

Verne arrived in Paris during a time of political upheaval: the French Revolution of 1848. In February, Louis Philippe I had been overthrown and had fled; on 24 February a provisory government, the French Second Republic, was established, but political demonstrations continued and social tension remained. In June, when barricades were erected in Paris, and the government sent Louis-Eugène Cavaignac to crush the insurrection. Verne entered the city shortly before the election of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte as the first president of the Republic, a state of affairs that would last until the French coup of 1851, in which Bonaparte was crowned ruler of the Second French Empire. In a letter to his family, Verne described the bombarded state of the city after the recent June Days Uprising.[24]

Verne used his family connections to make an entrance into Paris society. His uncle Francisque de Chatêaubourg introduced him into literary salons, and he frequented those of Mme de Barrère (a friend of his mother) and of Mme Mariani. While continuing his law studies, he developed a passion for the theatre and wrote numerous plays. He devoured the theatrical works of Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas, Alfred de Vigny, and Alfred de Musset, as well as those of Molière and Shakespeare, statuettes of whom he kept in his study for many years.[25] Verne later recalled: "I was greatly under the influence of Victor Hugo, indeed, very excited by reading and re-reading his works. At that time I could have recited by heart whole pages of Notre Dame de Paris, but it was his dramatic work that most influenced me, and it was under this influence that, at the age of seventeen, I wrote a number of tragedies and comedies, not to mention novels."[26]

During this period, Verne's letters to his parents were primarily concerned with expenses and with a suddenly appearing series of violent stomach cramps,[27] the first of many he would suffer from his life. Modern scholars have hypothesized that he suffered from colitis;[27] in any case, his illness seems to have been a hereditary one from his mother's side.[28] These medical concerns were exacerbated by a rumored outbreak of cholera in March 1849.[27][29] Yet another health problem would strike in 1851, when Verne suffered the first of four attacks of facial paralysis. These attacks, rather than being psychosomatic, were due to an inflammation in the middle ear, though this cause remained unknown to Verne during his life.[30]

In the same era, Verne was required to enlist in the French military, but was spared by the sortition process, to his own great relief. He wrote to his father: "You should already know, dear papa, what I think of the military life, and of these domestic servants in livery. … You have to abandon all dignity to perform such functions."[31] Verne's strong antiwar sentiments, to the dismay of his father, would remain steadfast throughout his life.[32]

Literary debut

Around 1848, in conjunction with Michel Carré, he began writing libretti for operettas, five of them for his friend the composer Aristide Hignard, who also set Verne's poems as chansons. For some years, he divided his attentions between the theater and work. However, some travelers' stories he wrote for the Musée des familles revealed his true talent: describing delightfully extravagant voyages and adventures with cleverly prepared scientific and geographical details that lent an air of verisimilitude. When Verne's father discovered that his son was writing rather than studying law, he promptly withdrew his financial support. Verne was forced to support himself as a stockbroker, which he hated despite being somewhat successful at it. During this period, he met Victor Hugo and Alexandre Dumas, who offered him writing advice.[citation needed]

Family

Verne also met Honorine de Viane Morel, a widow with two daughters. They were married on 10 January 1857. With her encouragement, he continued to write and actively looked for a publisher. On 3 August 1861, their son, Michel, was born. Michel married an actress against his father's wishes, had two children by an underage mistress, and buried himself in debts. The relationship between father and son improved as Michel grew older.

Verne's situation improved when he met Pierre-Jules Hetzel, a 19th century French publisher, who also published Victor Hugo, George Sand, and Erckmann-Chatrian, among others. Hetzel and Verne formed a successful team until Hetzel's death. Hetzel helped improve Verne's writings, which until then had been repeatedly rejected by other publishers. Hetzel read a draft of a Verne story about balloon exploration of Africa; the story had been rejected by other publishers for being "too scientific". Verne rewrote the story, which was published in 1863 in book form as Cinq semaines en ballon (Five Weeks in a Balloon).

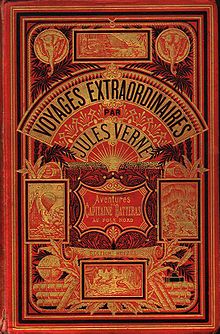

From that point, Verne published two or more volumes a year. The most successful of these are: Voyage au centre de la Terre (Journey to the Center of the Earth, 1864); De la Terre à la Lune (From the Earth to the Moon, 1865); Vingt mille lieues sous les mers (Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, 1869); and Le tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours (Around the World in Eighty Days), which first appeared in Le Temps in 1872. The series is collectively known as the Voyages Extraordinaires ("extraordinary voyages"). Verne could now live on his writings. But most of his wealth came from the stage adaptations of Le tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours (1874) and Michel Strogoff (1876), which he wrote with Adolphe d'Ennery.

In 1867, Verne bought a small ship, the Saint-Michel, which he successively replaced with the Saint-Michel II and the Saint-Michel III as his financial situation improved. On board the Saint-Michel III, he sailed around Europe. In 1870, he was appointed as "Chevalier" (Knight) of the Légion d'honneur. After his first novel, most of his stories were first serialised in the Magazine d'Éducation et de Récréation, a Hetzel biweekly publication, before being published in book form. His brother Paul contributed to 40th French climbing of the Mont-Blanc and a collection of short stories – Doctor Ox – in 1874. Verne became wealthy and famous.

Later years

On 9 March 1886, as Verne was coming home, his twenty-five-year-old nephew, Gaston, shot at him twice with a pistol. The first bullet missed, but the second one entered Verne's left leg, giving him a permanent limp that could not be overcome. This incident was hushed up in the media, but Gaston spent the rest of his life in a mental asylum. After the death of both his mother and Hetzel, Jules Verne began publishing darker works. In 1888, Verne entered politics and was elected town councilor of Amiens, where he championed several improvements and served for fifteen years. [citation needed]

Death

In 1905, while ill with diabetes, Verne died at his home, 44 Boulevard Longueville (now Boulevard Jules-Verne). Michel Verne oversaw publication of the novels Invasion of the Sea and The Lighthouse at the End of the World after Jules's death. The "Voyages extraordinaires" series continued for several years afterwards in the same rhythm of two volumes a year. It was later discovered that Michel Verne had made extensive changes in these stories, and the original versions were eventually published at the end of the 20th century by the Jules Verne Society (Société Jules Verne).

The original novels published in French by the Jules Verne Society are:

- Le secret de Wilhelm Storitz (The Secret of Wilhelm Storitz), 1985

- La Chasse au météore (The Meteor Hunt) - 1986. See The Chase of the Golden Meteor

- En Magellanie (In Maggelania), 1987; see The Survivors of the "Jonathan" (Les Naufragés du « Jonathan », 1909)

- Le beau Danube jaune (The beautiful yellow Danube), 1988; see The Danube Pilot (Le Pilote du Danube, 1908)

- Le volcan d'or (The Golden Volcano), 1989.[33]

In 1863, Verne had written a novel called Paris in the Twentieth Century about a young man who lives in a world of glass skyscrapers, high-speed trains, gas-powered automobiles, calculators, and a worldwide communications network, yet cannot find happiness and who comes to a tragic end. Hetzel thought the novel's pessimism would damage Verne's then-blossoming career, and suggested that he wait 20 years to publish it. Verne stored the manuscript in a safe, where it was discovered by his great-grandson in 1989. The long-lost novel was first published in 1994, and around the same time many other Verne novels and short stories were also published for the first time; these too are gradually appearing in English translations. [citation needed]

Legacy

Influence

The pioneering submarine designer Simon Lake credited his inspiration to Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea,[34] and his autobiography begins "Jules Verne was in a sense the director-general of my life."[35] William Beebe, Sir Ernest Shackleton, and Robert Ballard found similar early inspiration in the novel, and Jacques Cousteau called it his "shipboard bible."[36]

The aviation pioneer Alberto Santos-Dumont named Verne as his favorite author and the inspiration for his own elaborate flying machines.[37] Igor Sikorsky often quoted Verne and cited his Robur the Conqueror as the inspiration for his invention of the first successful helicopter.[34]

The rocketry innovators Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, Robert Goddard, and Hermann Oberth are all known to have taken their inspiration from Verne's From the Earth to the Moon.[38] Frank Borman, Jim Lovell, and William Anders, the astronauts on the Apollo 8 mission, were similarly inspired, with Borman commenting "In a very real sense, Jules Verne is one of the pioneers of the space age."[39]

Polar explorer Richard E. Byrd, after a flight to the South Pole, paid tribute to Verne's polar novels The Adventures of Captain Hatteras and An Antarctic Mystery by saying "It was Jules Verne who launched me on this trip."[35]

The preeminent spelologist Édouard-Alfred Martel noted in several of his scientific reports that his interest in caves was sparked by Verne's Mathias Sandorf.[40] Another influential spelologist, Norbert Casteret, traced his love of "caverns, abysses and underground rivers" to his avid youthful reading of Journey to the Center of the Earth.[41]

The French general Hubert Lyautey took much inspiration from the explorations in Verne's novels. When one of his more ambitious foreign projects was met with the reply "All this, sir, it's like doing a Jules Verne," Lyautey famously responded: "Yes, sir, it's like doing a Jules Verne, because for twenty years, the people who move forward have been doing a Jules Verne."[42]

Jean Cocteau cited both Around the World in Eighty Days and Verne's own 1874 dramatization of it as major childhood influences, calling the novel a "masterpiece" and adding "Play and book alike not only thrilled our young imagination but, better than atlases and maps, whetted our appetite for adventure in far lands. … Never for me will any real ocean have the glamour of that sheet of green canvas, heaved on the backs of the Châtelet stage-hands crawling like caterpillars beneath it, while Phileas and Passepartout from the dismantled hull watch the lights of Liverpool twinkling in the distance."[43]

Eugene Ionesco said that all of his works, whether directly or indirectly, were written in celebration of Captain Hatteras's conquest of the North Pole.[44]

The English novelist Margaret Drabble was deeply influenced by Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea as a child and remains a fervent admirer of Verne. She comments: "I used to be somewhat ashamed of my love of Verne, but have recently discovered that he is the darling of the French avant-garde, who take him far more seriously than we Anglo-Saxons do. So I'm in good company."[45]

Ray Bradbury counted Verne as a main influence on his own fiction as well as on literature and science the world over, saying "We are all, in one way or another, the children of Jules Verne."[46]

Other notable figures known to have been influenced by Verne include Fridtjof Nansen, Wernher von Braun, Guglielmo Marconi, and Yuri Gagarin.[47] Verne is also often cited as a major influence of the science fiction genre steampunk, though Verne's works themselves are not of the genre.[48]

Monuments

Because Verne was a longtime resident of Amiens, many places there are named after him, such as the Cirque Jules Verne. Amiens is the place where Verne is buried, and the house where he lived is now a museum. There is also the Jules Verne Museum in Nantes.

A restaurant built into the Eiffel Tower in Paris, France is named Le Jules Verne.[49] In June 1989, the Jules Verne Food Court opened at the Merry Hill Shopping Centre in the West Midlands of England; however, it had closed by the mid-1990s due to disappointing trade.[50]

Hetzel's influence

Hetzel substantially influenced the writings of Verne, who was so happy to finally find a willing publisher that he agreed to almost all changes that Hetzel suggested. Hetzel rejected at least one novel (Paris in the Twentieth Century) and asked Verne to significantly change his other drafts. One of the most important changes Hetzel enforced on Verne was the adoption of optimism in his novels. Verne was in fact not an enthusiast of technological and human progress, as can be seen in his works created before he met Hetzel and after Hetzel's death. Hetzel's demand for optimistic texts proved correct. For example, The Mysterious Island originally ended with all the survivors returning to the mainland but then always feeling nostalgic about their island.

Hetzel decided that these men should live happily ever after, so in the revised novel, they use their fortunes to build a replica of the island. Also, to not offend France's military ally of the time, the Russian Empire, the origins and past of the submariner Captain Nemo were widely changed from those of a Polish refugee avenging the partitions of Poland, and the death of his family during the repressions of the January Uprising, to those of an Indian prince fighting from beneath the seas against the British Empire following the Indian Rebellion of 1857.

See also

References

- ^ Roberts, Adam (2007). "7. Jules Verne and H. G. Wells". The History of Science Fiction. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 129–155. ISBN 0-230-54691-9. Retrieved 25 May 2011.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ UNESCO Statistics. "Index Translationum - "TOP 50" Author". United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- ^ "The History of Science Fiction", p. 48 by Adam Charles Roberts, Science Fiction (2000), Routledge; ISBN 0-415-19204-8.

- ^ a b c "Nantes et Jules Verne". Terres d'écrivains (in French). L’association Terres d’écrivains. 28 August 2003. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ^ Jules-Verne 1976, 1: "On his mother's side, Verne is known to be descended from one 'N. Allott, Scotsman', who came to France to serve in the Scots Guards of Louis XI and rose to earn a title (in 1462). He built his castle, complete with dovecote or fuye (a privilege in the royal gift), near Loudun in Anjou and took the noble name of Allotte de la Fuye."

- ^ Butcher 2007

- ^ Jules-Verne 1976, 3

- ^ Allotte de la Fuÿe 1956, 20

- ^ a b Lottmann 1996, 6

- ^ a b Verne 1890, §2

- ^ Compère, Cecile (1997). "Les vacances". Revue Jules Verne. 4: 35.

- ^ Allotte de la Fuÿe 1956, 26

- ^ Pérez, Ariel. "Jules Verne FAQ". Jules Verne Collection. Zvi Har’El. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Compère, Cecile (1997). "Jules Verne de Nantes". Revue Jules Verne. 4: 20.

- ^ Martin, Charles-Noël (1973). "Les amours de jeunesse de Jules Verne". Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne. 28: 79–86.

- ^ Dumas 1988, letter of 6 May 1853: "Je serai aussi aimable que le comporte mon caractère biscornu, avec les nommés Dezaunay ; enfin sa femme va donc entrevoir Paris ; il paraît qu'elle est un peu moins enceinte que d'habitude, puisqu'elle se permet cette excursion antigestative."

- ^ Compère 1997, 41 harvnb error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFCompère1997 (help)

- ^ Martin, Charles-Noël (1974). "Les amours de jeunesse de Jules Verne, 2e partie". Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne. 29: 103–113.

- ^ Dumas 1988, letter of 30 July 1848: "La mariée était vêtue de blanc, gracieux symbole de l'âme candide de son fiancé ; le marié était vêtu de noir, allusion mystique à la couleur de l'âme de sa fiancée !"

- ^ Chelebourg, Christian (1986). "Le blanc et le noir. Amour et mort dans les «Voyages extraordinaires»". Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne. 77: 22–30.

- ^ Lottmann 1996, 16

- ^ Verne, Jules. "La sixieme ville de France". Le Tour de Verne en 80 Mots. Gilles Carpentier. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ^ Compère 1997, 42 harvnb error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFCompère1997 (help)

- ^ Dumas 1988, letter of 17 July 1848: "Je vois que vous avez toujours des craintes en province ; vous avez beaucoup plus peur que nous n'avons à Paris … J'ai parcouru les divers points de l'émeute, rues St-Jacques, St-Martin, St-Antoine, le petit pont, la belle Jardinière ; j'ai vu les maisons criblées de balles et trouées de boulets. Dans la longueur de ces rues, on peut suivre la trace des boulets qui brisaient et écorniflaient balcons, enseignes, corniches sur leur passage ; c'est un spectacle affreux, et qui néanmoins rend encore plus incompréhensibles ces assauts dans les rues."

- ^ Sherard 1894, "The Residence of the Novelist"

- ^ Sherard 1894, "How He Was Educated"

- ^ a b c Lottmann 1996, 25

- ^ Dumas 1988, 372, letter of February 1855: "Je suis bien Allotte sous le rapport de l'estomac."

- ^ Dumas 1988, 274, letter of 17 March 1849: "Ma chère maman, le choléra est donc définitivement à Paris, et je ne sais quelles terreurs de malade imaginaire me poursuivent continuellement ! Ce monstre s'est grossi pour moi de toutes les inventions les plus chimériques d'une imagination fort étendue à cet endroit-là !"

- ^ Dumas, Olivier (2000). Voyage à travers Jules Verne (in French). Montreal: Stanke. p. 51.

La paralysie faciale de Jules Verne n'est pas psychosomatique, mais due seulement à une inflammation de l'oreille moyenne dont l'œdème comprime le nerf facial correspondant. Le médiocre chauffage du logement de l'étudiant entraîne la fréquence de ses refroidissements. L'explication de cette infirmité reste ignorée de l'écrivain ; il vit dans la permanente inquiétude d'un dérèglement nerveux, aboutissant à la folie.

- ^ Dumas 1988, 273, letter of 12 March 1849: "Tu as toujours l'air attristé au sujet de mon tirage au sort, et du peu d'inquiétude qu'il m'aurait causé ! Tu dois pourtant savoir, mon cher papa, quel cas je fais de l'art militaire, ces domestiques en grande ou petite livrée, dont l'asservissement, les habitudes, et les mots techniques qui les désignent les rabaissent au plus bas état de la servitude. Il faut parfois avoir fait abnégation complète de la dignité d'homme pour remplir de pareilles fonctions." Translation from Lottmann 1996, 29.

- ^ Lottmann 1996, 29

- ^ "Publications". Société Jules Verne. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ a b Strauss, Mark. "Ten Inventions Inspired by Science Fiction". Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ a b Gunn, James E. (2006). Inside Science Fiction. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. p. 210. ISBN 9780810857148.

- ^ Walter, Frederick Paul. "Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas: Introduction". Jules Verne Collection. Zvi Har’El. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ Griffith, Victoria. "The Fabulous Flying Machines of Alberto Santos-Dumont". ABRAMS. Abrams Books. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ Wallace, Richard. "Tsiolkovsky, Goddard and Oberth - Three Fathers of Rocketry". Space: Exploring the New Frontier. The Museum of Flight. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ "French Cheer Frank Borman". Daytona Beach Morning Journal: 37. 6 February 1969.

- ^ Šišovič, Davor (2003). "Jules Verne's sources for 'Mathias Sandorf.'" (PDF). Verniaan. 9: 26–27. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Science: Speleologist". Time. 32: 26. 21 November 1938. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ Margot, Jean-Michel (2011–12). "Editorial". Verniana. 4: v–viii. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ Cocteau, Jean (2000). Round the World Again in 80 Days. London: Tauris. pp. 1–2. ISBN 1860645925.

- ^ Butcher, William (2005). "Preface". The Adventures of Captain Hatteras. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192804650.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help) - ^ Drabble, Margaret. "What Writers are Reading". Time.com. Time Magazine. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ Butcher, William (1990). Verne's Journey to the Centre of the Self. London: Macmillan. p. xiii. ISBN 0333492935.

- ^ Butcher, William (1983). Jules Verne, Prophet or Poet?. Paris: Publications de l’INSEE.

- ^ Strickland, Jonathan. "Famous Steampunk Works". HowStuffWorks. Retrieved May 18, 2008.

- ^ "Le Jules Verne, restaurant at the Eiffel Tower in Paris". Dininginfrance.com. 2008-11-22. Retrieved 2011-06-27.

- ^ Peter Rhodes (2006-12-18). "Food court on Merry Hill menu « Express & Star". Expressandstar.com. Retrieved 2011-06-27.

Works cited

- Allotte de la Fuÿe, Marguerite (1956), Jules Verne, sa vie, son oeuvre, translated by Erik de Mauny, New York: Coward-McCann

- Butcher, William (2006), Jules Verne: The Definitive Biography, New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press

- Butcher, William (2007), "A Chronology of Jules Verne", Jules Verne Collection, Zvi Har'El, retrieved 3 March 2013

- Compère, Cecile (1997), "Le Paris de Jules Verne", Revue Jules Verne (in French), 4: 41–54

- Dumas, Olivier (1988), Jules Verne: avec la publication de la correspondance inédite de Jules Verne à sa famille (in French), Lyon: La Manufacture

- Lottmann, Herbert R. (1996), Jules Verne: an exploratory biography, New York: St. Martin's Press

- Jules-Verne, Jean (1976), Jules Verne: a biography, translated by Roger Greaves, London: Macdonald and Jane's

- Sherard, Robert H. (1894), "Jules Verne at Home", McClure's Magazine, retrieved 5 March 2013

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Verne, Jules (1890), "Souvenirs d'enfance et de jeunesse", Jules Verne Collection (in French), Zvi Har'El, retrieved 3 March 2013

External links

- Works by Jules Verne at Project Gutenberg

- Zvi Har'El's Jules Verne Collection, including a complete primary bibliography, a collection of academic scholarship, a Verne chronology, and a multilingual virtual library

- Annotated bibliography with summaries of Verne's works

- Jules Verne's works with concordances and frequency list

- A Jules Verne Centennial at the Smithsonian Institution

- The Jules Verne Collecting Resource with sources, images, and ephemera

- Maps from the Voyages Extraordinaires

- The Jules Verne Museum in Nantes

- The North American Jules Verne Society

- Centre International Jules Verne

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link GA