Australian contribution to UNTAG

| Australian Services Contingent | |

|---|---|

Australia's contribution to the United Nations Transition Assistance Group | |

| Active | 1989–1990 |

| Disbanded | 1990 |

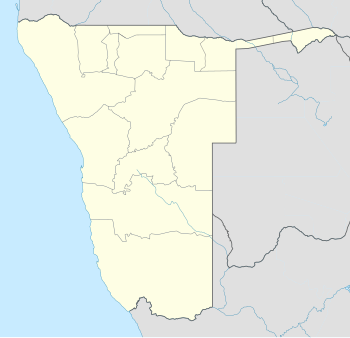

| Country | Namibia |

| Role | Engineering |

| Size | 300 |

| Part of | Military Component (MILCOM) |

| Decorations | Australian Active Service Medal, United Nations Medal |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | 1ASC: Colonel R.D. Warren, 2ASC: Colonel J.A. Crocker |

The Australian Services Contingent was the Australian Army contribution to the United Nations Transition Assistance Group (UNTAG) peacekeeping mission to Namibia. Australia sent two contingents of over 300 engineers to assist the Special Representative of the Secretary General in overseeing free and fair elections in Namibia for a Constituent Assembly in what was the largest deployment of Australian troops since the Vietnam War.[1]

The Australian mission was widely reported as a success. Colonel Crocker (Commander of 2 ASC) wrote that the November 1989 election was UNTAG raison d'etre and observed that the Australian Contingent's complete and wide-ranging support was critical to the success of that election and hence the mission – a fact that has been acknowledged at the highest level in UNTAG.[2] The two Australian Contingents achieved their mission without sustaining any fatalities, one of the few military units in UNTAG to do so.[3]

Overall, the UNTAG mission was highly successful in that Namibia became a democracy, without the racial segregation of the apartheid system, the security problems were largely overcome and the elections were declared free and fair. The military forces did not need to fire a shot during the entire operation.[4] Many observers at the time called UNTAG the most successful peacekeeping mission ever conducted.[1][5] UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon noted on 28 February 2008 in a message to the annual session United Nations Special Committee on Decolonization that "Facilitating this process constitutes one of the proudest chapters of our Organization's history".[6]

Background

South West Africa or Namibia was a German colony (German South-West Africa) from 1884 until it was annexed by South Africa during World War 1. After the war it was mandated to South Africa by the League of Nations. After World War 2 the United Nations asked South Africa to place Namibia under UN trusteeship but South Africa refused. Legal arguments continued until 1966 when the UN General Assembly resolved to end the mandate, declaring that henceforth South-West Africa was to come under the direct responsibility of the UN.[7][8]

In 1966, South-West Africa People's Organisation's (SWAPO) military wing, the People's Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN) began guerrilla attacks on South African forces, infiltrating from bases in Zambia. The first attack was the battle at Omugulugwombashe on 26 August. The war was a classic insurgent/ counter-insurgent operation. Initially the PLAN established bases in northern Namibia. Later PLAN were forced out of Namibia by the SADF and subsequently operated from bases in southern Angola and Zambia.[9]

The intensity of conflict escalated and South African Border War (also referred to as the Angolan Bush War) continued until 1989. The principal protagonists were the South African Defence Force (SADF) and the PLAN. Other groups involved included: South West African Territorial Force (SWATF) and National Union for Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) (both aligned with the SADF); and the People's Armed Forces for the Liberation of Angola (FAPLA) and Cuban forces as part of the Cuban intervention in Angola (both aligned with SWAPO).[10]

The nature of the closely intertwined Namibian War of Independence and South African Border War was typically cross-border conflict. Over more than 20 years the SADF mounted many cross‑border operations at PLAN bases, some of these operations extended 250 km into Angola. SADF units frequently remained in southern Angola to intercept PLAN combatants on their way south and succeeded in forcing PLAN to move to bases far from the Namibian border. Most of the PLAN insurgent operations took the form of small raids, directed at political activation, armed propaganda activity, recruiting personnel, raiding white settlements and disrupting essential services.[11]

The conflict further intensified in 1985 with the escalation of the Angolan Civil War. In that conflict South Africa provided support across the border (north) to UNITA. In opposition the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) financially backed an estimated two motorised infantry divisions of Cuban troops in what was called the Second Cuban intervention in Angola. In September 1987, Cuban forces came to the defence of the besieged Angolan Army FAPLA and stopped the advance of the SADF at the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale, the largest battle in Africa since World War II. General Magnus Malan wrote in his memoirs that this campaign marked a great victory for the SADF; but Nelson Mandela could not disagree more: Cuito Cuanavale, he asserted, "was the turning point for the liberation of our continent—and of my people—from the scourge of apartheid".[12] This battle led to the United Nations Security Council Resolution 602 on 25 November that demanded the SADF's unconditional withdrawal from Angola by 10 December 1987.[13]

A breakdown of forces in the Namibian Border Operational Area (BOA) in early 1989 at the time of the deployment of UNTAG ground forces included approximately 10,000 members of the SADF, approximately 21,000 soldiers of the South West African Territory Force (SWATF); approximately 6,400 members of the paramilitary forces comprising the Regular Police (SWAPOL), Special Force, and the Counter-insurgency Unit, which was also known as Koevoet. Opposing them, PLAN numbered between 5,000 and 8,000 although only 100 to 600 were estimated to be in Namibia at any one time.[14][15]

The UN process that led to the independence of Namibia commenced with Resolution 2145 (XXI) which was adopted by the UN General Assembly on 27 October 1966. This was followed by the passing of United Nations Security Council Resolution 264 which was adopted on 20 March 1969. In that resolution the UN assumed direct responsibility for the territory and declared the continued presence of South Africa in Namibia as illegal, calling upon the Government of South Africa to withdraw immediately. International negotiations for a peaceful solution to the Namibian problem increased. Finally in December 1978, in what was called the Brazzaville Protocol, South Africa, Cuba and Angola formally accepted United Nations Security Council Resolution 435 which outlined a blueprint for Namibian Independence. The agreement saw the phased withdrawal of Cuban forces from Angola over two years; it set 1 April 1989 as the date for the implementation of Resolution 435; and a goal for the reduction of South African forces to a total of 1,500 in Namibia by June 1989. The resolution established UNTAG with the mission to assist the Special Representative of the Secretary-General to carry out a mandate of ensuring the early independence of Namibia through free and fair elections under United Nations supervision and control. Resolution 435 authorised a total of 7,500 military personnel as the upper limit for UNTAG.[16][17][18]

It was not until 1988 that South Africa agreed to implement the resolution. This occurred when South Africa signed the Tripartite Accord (an agreement between Angola, Cuba and South Africa) at UN headquarters in New York. The accord recommended that 1 April 1989 be set as the date for implementation of Resolution 435.[19] This Accord was affirmed by the Security Council on 16 January 1989. UNTAG was then formally established in accordance with Resolution 632 on 16 February 1989.[20][21]

Australian political context

In the Official History of Australian Peacekeeping, Humanitarian and Post-Cold War Operations David Horner stated that the Australian Government, led by Robert Menzies had been loath to criticise South Africa during the 1950s.[22] Indeed, as late as 1961 Australia (together with Britain) abstained from a vote to condemn South Africa in the United Nations.[23] It was not until 1962 when Sir Garfield Barwick was External Affairs Minister that Australia voted for a UN resolution that condemned South Africa for its actions in South West Africa.[22] Initially while in opposition, and then leading up to the time when he was Prime Minister, Gough Whitlam was a vocal advocate of independence for Namibia. Over the following couple of decades Australia played a small but significant role in supporting Namibian independence. Political leaders from both sides of parliament including Prime Ministers Gough Whitlam and Malcolm Fraser were politically very active internationally in their support of independence for Namibia while in office. Australia was involved in the UN process almost from the start. Australia voted in favour of a UN Trust Fund in 1972, in 1974 Australia was elected to the UN Council for Namibia.[24] Australia pledged support for UNTAG at the inception of the UN plan for Namibia in Resolution 435 in September 1978.[25] Australia also made an important contribution to UN deliberations about Namibia while part of the UN Security Council in 1985–86.[26]

Behind the scenes, the composition of the force that Australia would contribute was not agreed in-principle until late 1978, other options that were discussed at the time were a logistic force or a battalion group.[27] However by October 1978, the Prime Minister of Australia, Malcolm Fraser, had publicly stated that he wanted to send a peace-keeping force to Namibia.[28][29] This was however not broadly agreed, in November 1978 an article in The Bulletin claimed that the Defence Department was 'dead against' a commitment, and in January 1979 The Daily Telegraph and The Canberra Times reported that Malcolm Fraser, Andrew Peacock and Jim Killen were involved in a row over the plan.[30] In February 1979 a cabinet submission stated that the UN proposal had a 'reasonable prospect' of success. Cabinet approved the commitment of an engineer contingent of 250 officers and men and a national headquarters and support element of 50 on 19 February 1979.[31] Horner noted that there was very little criticism of this decision in the press at the time and the decision was accepted without question.[31]

It is notable that after leaving government Mr Fraser continued to play an important role in international relations with respect to gaining independence for Namibia. In 1985 he chaired the United Nations hearings in New York on the Role of Multinationals in South Africa and Namibia. Fraser was also Co-Chair of the Commonwealth Eminent Persons Group campaigning for an end to apartheid in South Africa (1985–1986).[32][33]

The Hawke government's continued support of independence for Namibia from 1983 followed the Fraser and Whitlam governments before him. In the Official History, Horner stated that Australian peacekeeping 'blossomed' after Gareth Evans was appointed Foreign Minister in September 1988. Evans reconfirmed Australia's willingness to participate in UNTAG in October 1988, a month after his appointment.[34] Horner also said that the 'commitment was unusual' because it occurred a decade after the government's initial decision to be involved in February 1979.[35] Thus, after more than 10 years of consideration the Government reaffirmed the prior commitment of a contingent of 300 engineers to Namibia on 2 March 1989.[26]

Our contribution to UNTAG and our involvement in the Namibian settlement makes Australia party to what may be one of the United Nations' most substantial achievements for many years. We have been involved in this process from the start. Australia has been a member of the UN Council for Namibia since 1974. We pledged our support for UNTAG at the inception of the UN plan for Namibia in 1978. Australia also made an important contribution to UN deliberations about Namibia during our recent term on the UN Security Council in 1985-86. Our participation in UNTAG also builds on the constructive role successive Australian governments have played on southern African issues. I pay particular tribute to the achievements of my predecessor Malcolm Fraser in this regard.

Just prior to the deployment, the Prime Minister of Australia, Bob Hawke, said in Parliament that Namibia was a very large and important commitment for Australia, comprising almost half of the Army's construction engineering capability. He went on to say that "Our effort in Namibia will be the largest peacekeeping commitment in which this country has ever participated. It may also be the most difficult." The Minister for Defence Kim Beazley noted that "the UNTAG deployment was (by a large margin) Australia's biggest peacekeeping effort yet, and it is probably our most difficult".[26]

It is also noteworthy that the sending of the contingent to Namibia had bi-partisan support (unlike the commitment of soldiers to Vietnam) over 20 years earlier.[36]

Prior to the deployment the South African authorities threatened to veto the involvement of Australian peace-keeping troops because of doubts concerning their partiality. This followed from the establishment by the Australian Government of a Special Assistance Program for South Africans and Namibians (SAPSAN) in 1986 with a view to assisting South Africans and Namibians disadvantaged by apartheid. The focus of SAPSAN was on education and training for people of South Africa and Namibia. Some humanitarian assistance has also been provided. A total of $11.9 million was spent under SAPSAN during 1986–1990.[37][38]

In the Official History, Horner described the Australian deployment to Namibia as a 'vital mission' being the first major deployment of troops to a war zone since the Vietnam War. Horner noted that in 1988 Australia only had 13 military personnel deployed on multinational peacekeeping operations, and with few exceptions the numbers of Australians committed to such activities had not changed much for over 40 years (since the Korean War). The successful deployment of over 600 Engineers to Namibia in 1989 and 1990 was pivotal to changing Australia's approach to peacekeeping and paved the way for the much larger contingents sent to Cambodia, Rwanda, Somalia and East Timor. The deployment of a significant force to Namibia profoundly affected Australia's defence and foreign policies.[1][39]

The Australian Contingent and UNTAG

Command

The military component was commanded by Lieutenant-General Dewan Prem Chand of India with the main military UNTAG Headquarters being based in Windhoek, Namibia's capital and largest city.[40]

Commanders of the Australian Contingent were Colonel Richard D. Warren (1 ASC)[41][42] and Colonel John A. Crocker (2 ASC).[43][44][45] Other senior appointments included Second-in-command, Lieutenant-Colonel Kevin Pippard (1 ASC) and Lieutenant-Colonel Ken Gillespie (2 ASC) and Officer Commanding 17th Construction Squadron, Major David Crago (1 ASC)[46] and Major Brendan Sowry (2 ASC).[26][47]

Mission and role of UNTAG

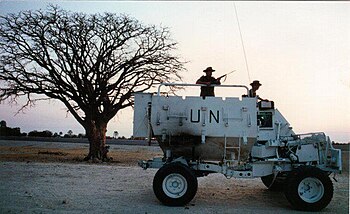

UNTAG's mission was to monitor the ceasefire and troop withdrawals, to preserve law and order in Namibia and to supervise elections for the new Government of Namibia.[48] Horner described it as "an extremely complex mission" in the Official History.[49]

The role of UNTAG was to assist the Special Representative of the Secretary General (SRSG) in overseeing free and fair elections in Namibia for a Constituent Assembly. The elections were to be carried out by the South African Administrator General under UN supervision and control.[Note 1] This Assembly was to then draw up a constitution for an independent Namibia. The role of UNTAG was to assist the SRSG in ensuring that all hostile acts were ended; South African troops were confined to base and ultimately withdrawn; discriminatory laws were repealed; political prisoners released; Namibian refugees were permitted to return (called 'returnees'); intimidation prevented; and law and order was impartially maintained.[51][52]

UNTAG was the first instance of a large-scale multidimensional operation where the military element supported the work of other components concerned with border surveillance; monitoring the reduction and removal of South African military presence; organizing the return of Namibian exiles; supervising voters' registration; and preparing, observing, and certifying the results of national elections.[53][54]

Role of the Australian Contingent to UNTAG

The role of the Australian Contingent was very broad for an army engineering unit. The role required the unit to "provide combat and logistic engineer support to UNTAG", this included the UN Civilian as well as Military force components. The role included construction and field engineering and also initially deployment as infantry to support Operation Safe Passage.[55]

The Prime Minister of Australia said in Parliament at the time that "The settlement of the long and complex issue of Namibian independence is an important international event. It is an event in which Australia has played, and will continue to play, a substantial part ... Namibia is a large, arid, sparsely populated and underdeveloped country which has been a war zone for many years. Our engineers will build roads, bridges, airstrips and camps for UNTAG. They will have the very serious task of clearing mines which have been laid by the various contending forces along the border between Angola and Namibia."[26]

Organisation

The Australian Contingent organisation was structured as follows:[56][57]

- a Headquarters (Chief Engineer ASC UNTAG) containing operations, works, accommodation, communications, finance, logistic and personnel cells;

- a Construction Squadron group based on the 17th Construction Squadron (Royal Australian Engineers) which contained two construction troops (8 and 9 Troop), 14 Field Troop, a resources troop, a plant troop and the attached Royal Australian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers workshop.

Composition of the contingents

Each contingent consisted of over 300 soldiers.

- 1 ASC consisted of 304 members and was principally drawn from three units, the 17th Construction Squadron, associated Royal Australian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (workshop) and 14 Field Troop from 7 Field Squadron in Brisbane. The contingents also included soldiers from the Royal Australian Corps of Signals, Royal Australian Army Pay Corps, Australian Army Legal Corps, Royal Australian Corps of Military Police, Royal Australian Corps of Transport, Royal Australian Army Ordnance Corps, Australian Army Catering Corps and the Australian Army Medical Corps.[58]

- 2 ASC consisted of 309 personnel and its members were drawn from 78 different units. The Contingent included 14 members of the Corps of Royal New Zealand Engineers (RNZE), 5 Australian Army Reserve (ARES) members and one Royal Australian Air Force officer (Flight Lieutenant Craig Forster). The second contingent also included 14 New Zealand engineers (Lieutenant Jed Shirley) who were spread throughout the squadron. The second contingent also included a detachment from the Royal Australian Corps of Military Police, led by Sergeant Tim Dewar.[58]

In addition to the military force, it is notable that a number of other Australians served with UNTAG including 25 electoral observers from the Australian Electoral Commission.[59]

For the duration of the deployment, the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and Defence had agreed to jointly fund a temporary 'Australian Liaison Office' in Windhoek to be manned by two DFAT personnel headed by Nick Warner.[60]

Force preparation and deployment

The First 10 Years

Australian Army involvement in UNTAG was formalised in February 1979 by Cabinet which approved the plan to commit the 17th Construction Squadron, Royal Australian Engineers and Workshop as the main force for deployment.[31] The squadron was to be supplemented by a Field Troop and by members posted in from other units throughout the Army to bring the squadron up to a deployment strength of 275 personnel. A Headquarter Unit was to be formed to support the Chief Engineer on the UNTAG Military Headquarters. The total strength of the ASC was to be over 300 all ranks in what was known as Plan Witan.[61] The unit had been placed on eight weeks notice in July 1978 which was reduced to a weeks notice to move in February 1979.[61]

There was however no agreement or settlement between South Africa and SWAPO, so an order to move was never issued. Horner wrote that as the weeks passed the unit found it difficult to continue training because all its vehicles, equipment and plant were either in boxes or in a state ready for transhipment.[62] The notice to move reverted to 30 days in June and pushed out to 42 days in September 1979 and the unit was formally released from standby.[63] The notice to move was increased to 60 days in March 1982 and finally seventy-five days in November 1986. In July 1987 all remaining specific readiness requirements were removed.[64]

Activation

Horner wrote that the government had been following the course of negotiations but in view of the history of false alarms they were not inclined to react until Angola, Cuba and South Africa signed the protocol in Geneva in August 1988.[65] Within two weeks the UN had written to Australia asking Australia to reconfirm its previous commitment, and within a month Cabinet had reaffirmed the prior commitment from a decade earlier. The Chief of the Defence Force General Peter Gration then placed the unit on 28 days notice to move.[66]

After notice was reactivated the detailed planning recommenced, essentially from scratch. However, the changes made to the organisation of the contingent approved ten years earlier were only minor.[67] After many years of 'notice' there was still some reservation that deployment would ever occur. The Government and army was cautious about the timing of the commitment of funds and significant funding was only released in late 1988, a few months before deployment. The squadron's equipment deficiences had a value of $16 million, but there was a need to buy $700,000 of equipment immediately. [68] The reluctance to commit funds ultimately greatly reduced the training of the deployed forces; indeed Senator Jo Vallentine said in Parliament that the Namibia operation nearly fell apart through lack of advance funding and Senator Jocelyn Newman called it disgraceful.[69][70] Horner noted in the Official History that the UN General Assembly did not approve the UNTAG budget until 1 March 1989, less than two weeks before the advance party deployed, and after the deployment of the start-up team.[60]

Gration then formally authorised Operation Picaresque on 3 March 1989.[60][Note 2]

In addition to lack of funds, there was little intelligence on Namibia. Horner stated that Namibia was generally unknown to the Australian public, the policy-makers and to the troops and civilians who deployed there.[34]

Build up and Deployment

The first staff were posted to the new contingent Headquarters at Holsworthy Barracks in September 1988. At the same time Major J.J. Hutchings was deployed as a liaison officer to the UN HQ in New York.[67][71]

As early as October, the CDF had formally tasked the CGS to raise, train, equip and support the force for Namibia.[67] By December the two units that formed 1 ASC had been raised from more than 30 different units of the Australian Army and were being trained and prepared for deployment.[68] Equipment, vehicles and weapons were procured and transferred from across the Army and were prepared at Moorebank. This included the painting of all vehicles and major equipment items in UN livery and the packaging of the items for transport to Namibia. During the build up it was recognised that the families required support during the deployment and Network 17 was established to support the mostly Sydney based soldiers and officers' families.[72]

The Australian Liaison Officer to the UNHQ was sent to Namibia as a member of the start-up team, arriving in Windhoek on 19 February 1989.[67] The Contingent Commander, Colonel R.D. Warren, attended the Contingent Commanders Briefing at the UN HQ from 22 to 24 February 1989[68] and then flew with Prem Chand to Frankfurt, West Germany to meet the other senior members of UNTAG.[73]

This will not be an easy process. Since the Transition Period in Namibia began on 1 April, there have already been serious clashes between members of SWAPO on one hand and elements of the Namibian police and the South African Defence Forces on the other. The clashes have been serious and bloody. More than two hundred people have been killed. The situation is still tense and serious.

The 1 ASC advance party, comprising 36 Officers and men, were deployed by USAF C5 Galaxy via Learmonth and Diego Garcia to Windhoek. They arrived at 2pm on 11 March 1989 and were met by the Australian Ambassador to South Africa, Colin MacDonald, the Australian contingent commander, Colonel Warren, and Major Hutchings. The 17 Construction Squadron advance party of 10 personnel deployed by road to Grootfontein on 13 March 1989. The squadron's advanced echelon, comprising 59 personnel including 14 Field Troop, arrived by USAF C5 Galaxy at Grootfontein on 14 March 1989.[74]

The remainder of 1 ASC were farewelled by the Prime Minister of Australia, Bob Hawke, at a farewell parade at Holsworthy Barracks on 5 April 1989. The main body then deployed by Boeing 707 Aircraft from the Royal Australian Air Force on 14 April.[75]

The force deployed with a large quantity of construction and other equipment including 24 Land Rovers, 19 Unimog all-terrain vehicles, 26 heavy trucks, 43 trailers, 8 bulldozers and a range of other road making plant such as graders, scrapers and rollers. The supporting workshop added a further 40 vehicles and over 1,800 tonnes of stores were shipped with the contingent's equipment.[26] All up there were over 200 wheeled and tracked vehicles and trailers, and a large quantity of dangerous cargo (demolition explosives and ammunition). The UN hired the MV Mistra, a Roll-on/roll-off (RO/RO) ship, for the deployment. It departed Sydney on 23 March and the equipment was unloaded at Walvis Bay in mid April. It was then moved by road and rail to the South African Defence Force Logistics Base at Grootfontein.[76]

Operations

Operations Safe Passage and Piddock

By 31 March, the 14th Field Troop had completed its mine awareness training and only Lieutenant Steve Alexander and five others remained at Oshakati, the main SADF base in the north of the country. In the early hours of 1 April an SADF aircraft started dropping flares and mortar rounds landed near the base. This signalled the start of an intense period of conflict. Alexander's team was quickly withdrawn to Grootfontein. What has occurred was the infiltration of a large number of PLAN combatants (about 1,600) re-entering Namibia from Angola.[77] Accounts differ but Hearn states that all of those interviewed at the time made it clear that "they did not enter Namibia for war, but to seek out the UN".[78] The large size of the PLAN forces and the very small number of deployed UN forces (less than 1000 at the time) meant that the UN had very little intelligence and was unable to respond in force. Sitkowski wrote that the UN should have been informed about the high probability of a SWAPO infiltration but this did not occur.[79] The Australians were the first to know about the incursion, but they only found out informally via church sources at the Pastoral Centre which was the accommodation for the Headquarters staff.[80]

The UN only had two police observers in the north of the country at the time. The South African Government placed pressure on the UN to allow its forces to leave their bases and respond. On 1 April the SRSG authorised the SADF to leave their bases and they responded in force. Over the next three weeks it has been estimated that 251 PLAN combatants were killed for the loss of 21 members of the SADF and other Security Forces.[Note 3]

The SWAPO incursion became a very complex political issue however by 9 April 1989 an agreement was reached at Mount Etjo (called the Mount Etjo Declaration) which called for the rapid deployment of UNTAG forces and outlined a withdrawal procedure for PLAN soldiers called Operation Safe Passage. Operation Piddock was the name for the Australian part of the operation. Horner wrote that if UNTAG were to pay any role in ending the fighting, it was obvious that the Australians would be the key component. This was however complex and required authority from the CDF and the Minister for the Australian troops to supervise the withdrawal of the insurgent forces. This task required the Australian Army engineers and British signallers to work as infantry and man border and internal assembly points. At the time these were the only military units that could be re-deployed quickly to northern Namibia.[81]

The aim of the operation was to facilitate the withdrawal of PLAN combatants. A total of nine assembly points were established with 10 soldiers and five military observers at each. Most of the assembly points also had intense media scrutiny. The intention of the operation was that PLAN combatants would assemble at these points, then they would be escorted across the border north to the 16th parallel to their bases of confinement. The operation did not prove successful. Very few PLAN combatants transited through these points, in the main they withdrew across the border by walking out. It was estimated that 200 to 400 PLAN members remained in Namibia, being absorbed into the local community. Agreement was subsequently reached in late April that the SADF personnel be restricted to their bases from 26 April; and in effect from this date hostilities largely ceased.[82][83][84]

This was a stressful time for the Australian soldiers deployed to these check-points. The South Africans were determined to intimidate the UN forces, and SWAPO casualties occurred in the immediate vicinity of several of the check-points. The South Africans set up in force immediately adjacent to many of the check-points, pointed machine-guns at the Australians and demanded that they hand over SWAPO soldiers that had surrendered. The Australian and British soldiers were outnumbered and out-gunned.[85] Despite the fact that only nine SWAPO appeared at the points, politically the operation was a success. Colonel Donaldson, the commander of the British contingent said that 'the world press showed Australian and British soldiers standing up to a bunch of South African bullies'.[86] The fact that the Australian soldiers survived this operation without casualty was said to be a tribute to the 'training standards of the Australian Army and perhaps, a bit of good luck'.[43] The conclusion of Operation Piddock meant that the Australians were able to begin their engineering tasks.[87]

Return of refugees ("Returnees")

The UN plan required that all exiled Namibians be given the opportunity to return to their country in time to participate in the electoral process. Implementation was executed by the UNHCR supported by a number of other United Nations agencies and programmes. In Namibia, the Council of Churches was UNHCR's implementing partner. Most returning Namibians came back from Angola but many came from Zambia and a small number came from 46 other countries following proclamation of a general amnesty. The logistics of managing the "Returnees" was largely delegated to the Australian Contingent.[88]

Three air and three land entry points were established as well as five reception centres. Four of the reception centres for returning Namibian exiles were designed by Namibia Consult Incorporated under the directorship of Klaus Dierks and then constructed by the Australian Contingent. The centres were located at Dobra, Mariabronn near Grootfontein, and at Ongwediva and Engela in Ovamboland. They were administered under the auspices of the Repatriation, Resettlement and Reconstruction Committee of the Council of Churches in Namibia (CCN).[89]

The 8th Construction Troop (Lieutenant Geoff Burchell) constructed a camp and managed the reception centre at Engela, less than 5 kilometres from the Angolan border; and the 9th Construction Troop (Lieutenant Andrew Stanner) constructed a similar camp and managed the reception centre at Ongwediva. The South Africans continued to intimidate and endeavoured to disrupt plans but by this stage of the operation their actions had little effect. In late April an SADF aircraft dropped flares at night over the 9th Construction Troop base at Ongwediva and explosions (possibly mortar rounds) were heard nearby.[90][88]

Security, services and logistics at the reception centres was provided by the military component of UNTAG. A series of secondary reception centres was also established. Movement by returnees through the centres was quick and effective. The repatriation programme was very successful. The UN official report stated that the psychological impact of the return of so many exiles was perceptible throughout the country. There were some reported problems in the north when ex-Koevoet elements searched villages for SWAPO returnees however this matter was kept under constant surveillance by UNTAG's police monitors. By the end of the process, 42,736 Namibians had been brought back from exile.[88]

Accommodation and other works

Much of the effort for the remainder of the duration of the first contingent was dedicated to the provision of accommodation for the electoral centres and police stations. These were typically manned by only two or three police or civilian electoral staff and were almost always located in small remote villages. Buildings were leased, a large number of caravans purchased and deployed and prefabricated buildings were constructed in about fifty locations. Much of this was done by the Resources troop (Lieutenant Stuart Graham) and centrally controlled by the squadron construction officer (Captain Shane Miller).[92]

The largest plant task undertaken during the deployment was the construction of an airstrip at Opuwo. The squadron commander, Major David Crago described how the road network in Namibia was better than expected and in retrospect the squadron brought too much heavy road-making equipment. The squadron deployed twenty members of the Plant Troop (Captain Nigel Catchlove) to Opuwo. Over a period of four months Sergeant Ken Roma constructed an all-weather strip in one of the most remote parts of Namibia.[93]

Force Rotation

Planning for the second contingent commenced as soon as the first contingent had deployed. Colonel John Crocker was appointed as the contingent commander and was given the difficult task of creating the second contingent.[43] Unlike the first contingent which was composed primarily of the existing 17th Construction Squadron with the squadron structure maintained, the second contingent had to be built from scratch.[58]

The second contingent took up duty in Namibia in September / early October 1989.[94][95]

Preparing for the elections

The security environment in Namibia changed in the lead up to the election. This included violence in Namibia as well as an increase in fighting between the Angolan government (FAPLA) and rebel (UNITA) troops across the border in Angola.[96] The Australian contingent was not directly involved in "dealing with the violence" but the increased violence changed the nature of the mission. It was initially envisioned that the military component of UNTAG would only provide communications and logistic support to the election. In September the role was broadened to include hundreds of electoral monitors, and in October after more detailed planning and reconnaissance of all polling stations the Australian Contingent deployed a ready-reaction force. At the same time the 15th Field troop (Lieutenant Brent Maddock) was deployed to make the 'first entry' by Australian troops into a live minefield since the Vietnam War.[97]

Operation Poll Gallop

Operation Poll Gallop was the name given to the largely logistic operation to support the Namibian elections. Activities commenced with 1 ASC from May 1989 onward, but became the primary task for 2 ASC.[98][44]

- Service support: Support was provided to approximately 500 electoral centres and police stations through the siting and erection of either permanent or portable accommodation as well as the provision of essential services. UNTAG deployed over 350 polling stations, the Australian contingent constructed and provided support (including sanitary facilities) at 120 of the polling stations in the northern areas of Kaokoland, Ovamboland and West Hereroland.[99]

- Construction engineering: including the construction, modification or upgrade of UNTAG working and living accommodation, the provision of essential services (power, water and air traffic control facilities) and the maintenance and upgrade of roads.

- Ready Reaction Force: The squadron formed a reinforced troop (50 soldiers) mounted in Buffel mine-proof vehicles as a ready reaction force located at Ondangwa. The ready reaction force practiced deploying to each of the 15 most sensitive locations in Ovamboland. They also practised actions to be taken "in stabilising a hostile but not physically violent situation" in which Australians might be involved. On two separate occasions during the November 1989 election, the ASC's Ready Reaction Force was used to disperse rioters.[100]

- Australian military electoral monitors: The Australian contingent also provided a team of thirty electoral monitors, headed by Lieutenant Colonel Peter Boyd, the legal officer for the second contingent.[100]

Colonel Crocker, Commander of 2 ASC wrote that "For much of the mission, but particularly during the lead-up to the election, all members of the ASC worked, often well away from their bases, in a security environment which at best could be termed uneasy and on many occasions was definitely hazardous. The deeply divided political factions, which included thousands of de-mobilised soldiers from both sides, had easy access to weapons including machine guns and grenades. This situation resulted in a series of violent incidents including assassinations and reprisal killings which culminated in the deaths of 11 civilians and the wounding of 50 others in street battles in the northern town of Oshakati just before the election".[43] Land mines and unexploded ammunition continued to cause injury and death, even during the week of the election there were incidents.[101]

Post-election and Return to Australia

After the election the contingent was able to focus almost exclusively on engineering works tasks. In addition to ongoing maintenance, these included taking over barracks and accommodation from the SADF but also included twelve non-UNTAG tasks in support of the local community as nation-building exercises.[91] These included:

- Opuwo airfield: The major task was the completion of the upgrade works of the airfield at Opuwo which had been commenced by the first contingent. A detachment from Captain Kurt Heidecker's plant troop supported by a section from the 9th Construction Troop worked over Christmas to complete these works which included resurfacing and shaping the runway, drainage and installation of culverts.[91]

- Andara Catholic Mission hydroelectric plant: A team under Lieutenant Nick Rowntree upgraded a 900 metre supply channel for the hydro-electric plant.[91]

- Classrooms in Tsumeb: Sappers from the rear-party of the squadron also constructed a number of classrooms for an Anglican school in a black neighbourhood in Tsumeb, using funds provided by the Australian Liaison Office.[91]

Other tasks carried out by the squadron included Operation Make Safe which took place in February and March 1990. In this operation the field troop conducted a reconnaissance of 10 known minefields, repaired perimeter fences and installed signs.[102]

2 ASC commenced preparations for its return to Australia in December 1989. Intensity increased from January 1990 with the cessation of new works, reduced manning of forward bases and the packing and sea preparation of stores and equipment. The Australian forces returned to Australia in four sorties on chartered commercial aircraft, the first departing Namibia on 6 February. The contingent's equipment was returned to Australia aboard the MV Kwang Tung which departed from Walvis bay on 22 February.[103] The withdrawal included support from logistic experts from Australia, a psychologist to conduct end-of-tour debriefings, and a finance officer. The last demolition task was undertaken at Ondangwa on 25 March and the last elements of the rear party left Namibia on 9 April 1990.[104]

Commendations and the Award of Honour Distinction

Nobel Peace Prize

Governments around the world linked the award of the Nobel Peace Prize to United Nations Peacekeepers in 1988 to the UNTAG operation; however the award was shared by peacekeepers and peace-keeping operations the world over. Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, the Secretary-General of the United Nations mentioned a number of UN peace-keeping operations including Namibia in his Nobel Lecture in Oslo on 9 January 1989. Senator Graham Richardson also made similar comments in the Australian Senate.[105][106][107]

CGS Commendation

The Australian Contingent UNTAG was awarded a Chief of the General Staff Commendation from Lieutenant General L.G. O'Donnell, the Chief of the General Staff in March 1990. The Commendation was as follows:

I commend the Australian Contingent UNTAG for its exemplary performance in Namibia. Its major contribution to the peace process has been praised by the United Nations in Namibia for professionalism and sensitivity in fulfilling its role. The Contingent comprised three units; Headquarters Chief Engineer (UNTAG), 17th Construction Squadron (UNTAG) and 17th Construction Squadron Workshop (UNTAG). It was the largest Australian peacekeeping force committed in support of United Nations operations. The Contingent demonstrated its flexibility of purpose when, in April 1989, it was required to adopt an armed monitoring role during a time at which peace and free elections were in jeopardy. Under the constant vigil of the international press this highly sensitive task was carried out with great effectiveness. A potentially explosive situation was stabilised and a free and fair election program developed as a result. The complex operation of facilitating the return of over 40 000 refugees, overseeing the electoral process, clearance of mines and explosives and conduct of construction programs in support of the United Nations and the Namibian people, was carried out with unparalleled success. The members of the Contingent have brought great credit to themselves, the Australian Defence Force and Australia. The manner in which the Contingent completed tasks leading to the independence of a new nation has gained world-wide recognition and is in the highest traditions of the Australian Defence Force.

"Commendation, Australian Contingent UNTAG". Army Headquarters, Canberra. 2 March 1990. {{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires |journal= (help)[108]

The award was presented to both contingents at a parade in Holsworthy on 2 March 1990 to honour those that had served in eleven UN and other peacekeeping operations by the Minister for Defence, Kim Beazley.[Note 4]

Honour Distinction

In April 2012 the Chief of Army Lieutenant General David Morrison, AO approved a recommendation for the award of the first Honour Distinction to 17th Construction Squadron. This is awarded to units or sub-units to recognise service under operational conditions in security-related, peace keeping and peace enforcement and similar operations.[110]

The Citation for the award reads:

17 Construction Squadron is awarded the Honour Distinction, Namibia 1989–1990, in recognition of its creditable performance in support of the United Nations Transition Assistance Group operation to manage the transition of Namibia to independence in 1990. Despite being deployed to provide engineering support, when the ceasefire broke down at the start of the mission, members of the squadron helped establish Assembly Points, which enabled the mission to continue. This activity was conducted in the face of hostility from elements of the former colonial power and personal danger arising from the breakdown of the cease fire. Later, 17 Construction Squadron became involved in the election process itself, providing security, transport and logistic support to election officials, monitors, other UN personnel, voters and polling stations. Members of 17 Construction Squadron ensured that, as much as possible, the election was able to proceed without interruption or interference and ensured that all parties were free from intimidation or duress. With the selfless support of individuals from other units of the Australian Defence Force, 17 Construction Squadron played a key role in the smooth and effective transition of Namibia from colonial rule to independence. The Squadron performed a role well beyond what was expected and brought great credit on itself, the Australian Army and Australia.

"Letter from the Chief of Army to the Governor General". Army Headquarters, Canberra. 10 April 2012. {{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires |journal= (help)[111]

The award will be presented to the unit by the Governor General on 11 May 2013.[111]

Operational and other issues

Force or Chief Engineer

The appointment of Colonel Warren as Chief Engineer was opposed by both Marrack Goulding (the UN Undersecretary General for Special Political Affairs) and Cedric Thornberry (the Director of the Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General). The UN had planned on a civilian filling this role working primarily with civilian contractors. This was a reverse of the arrangement for all subsequent UN missions in which the senior engineer was a civilian. The UN Headquarters resisted the appointment of Colonel Warren until the last minute, with final approval only given on 1 March. Colonel Warren recalled that this gave him 'an abnormal amount of authority and a remarkable degree of responsibility'.[65]

Weapons and Rules of Engagement

The contingents were faced with a number of issues with respect to weapons and rules of engagement:

- Rules of Engagement: A major issue for the contingents was with respect to Rules of Engagement (ROE) and Orders for Opening Fire (OFOF). In 1989 the UN did not have any doctrine in this area and was unable to develop any during the mission. The Australian contingent used standard ROE prepared prior to the deployment.[85]

- Machine guns: It was also notable that the UN required the Australians to deploy without the standard-issue belt-fed M60 machine gun which was the standard section level heavy weapon of the army at the time. Instead, the contingent was required to deploy with Second World War-vintage Bren light machine guns, as these used only a 30-round magazine. The weapons had however been rebuilt to accept 7.62mm ammunition.[85][76]

- Deployment without weapons: On a number of occasions soldiers were asked to deploy without weapons by the UNTAG Civilian officials. Early in the deployment Lieutenants Burchell and Stanner were asked to conduct a reconnaissance by UNHCR without weapons. Permission was refused. Close to the election, the Australian army military monitors were asked to deploy in civilian clothes without weapons which then occurred.[100][112]

Land mines and UXO

Mines were used by both the SADF and SWAPO and became a major feature of the war, giving rise to the development of the mine protected vehicles (MPV). The SADF laid recognised, marked and fenced, anti-personnel minefields typically as perimeter protection to bases and vital assets. The SADF reported laying 45,000 mines during the conflict of which 3,000 were unaccounted for when UNTAG arrived.[90] SWAPO employed mines as a means of ambushing or intimidation. Mines were laid individually or in clusters and Anti-tank mines were often stacked. Mines were sourced from South Africa, USSR, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia. After initial training by the SADF's 25th Field Squadron, one of the early tasks of the Field Troop was to conduct mine awareness training for the other contingents. For the remainder of the deployment much of the work of the Field Engineers was area search, clearance of exposed mines, marking minefields and route clearance.[113][90]

Colonel John Crocker, the Commander of the 2nd Contingent wrote that "For the first time since the Vietnam War, Australian Sappers hand cleared their way into live minefields on seven separate occasions to destroy exposed mines. Similar mines killed several civilians and many animals during the mission. Field engineers of the contingent destroyed over 5,000 items of unexploded ordnance (UXO) ranging from artillery shells, through RPG rockets to grenades. UXO, a legacy of the 20-year Bush War, posed a major hazard to local inhabitants in the northern provinces and to UNTAG personnel in that area".[43]

To support the deployment the UN leased a number of mine protected vehicles off the SADF. Most were the Buffel but smaller numbers of Casspir and the 'Wolf' vehicles were also leased. These vehicles had excellent mobility and were well suited to operations in the harsh Namibian terrain.[114][90][115][116]

The contingent also put effort into trialling Thermal Intensifier technologies in what was believed to be the first time this technology was ever deployed operationally.[90][117]

Radio communications

One of the major difficulties early in the deployment to Namibia was poor radio communications. The Australian Contingent was equipped with PRC-F1 HF radios (manufactured by AWA) first issued to the Australian Army in 1969. Output power was limited to either 1 Watt or 10 Watts PEP. The combination of the March 1989 geomagnetic storm, distance, sand, dry atmospheric conditions and high water table effectively blocked almost all HF radio communications for the first couple of months of the deployment. Detachments were often out of radio contact for extended periods, with no satisfactory alternate means of communication except couriers. Because the Australian Contingent operated over large distances, with Troop deployments often 300–700 km from Squadron or Force Headquarters, courier communications often took days. Later in the deployment the UN provided the Contingent with a quantity of higher powered (100W) state-of-the-art HF radio equipment (Motorola Micom X).[118]

Controversy and intimidation

A number of observers noted that the UNTAG soldiers were not particularly popular with Namibia's 80,000 white population. Shortly after the Australian advance party arrived in Namibia, a pro-Pretoria newspaper accused Australian officers of breaching UN impartiality by attending a cocktail party at which the leading members of SWAPO were present. The incident was widely reported in the international press.[75][47][119] Soon after, four Australian and four British soldiers were beaten up by a large crowd in Tsumeb, about 70 km from the Grootfontein Squadron Headquarters.[120] In the first few weeks of the deployment there were a large number of occasions where SADF soldiers discharged their firearms in the general direction of the Australian contingent or pointed firearms at Australians as a method of intimidation.[121] Corporal Paul Shepherd reported that during Operation Piddock an SADF soldier threw a grenade at his Assembly Point near Ruacana (that did not explode) and that during the night the South Africans fired in their direction, putting bullet holes in their Unimog truck.[122]

There were very few other concerns. At least 10 soldiers were hospitalised and treated for malaria but there were few serious injuries and no fatalities.[41][90][123]

Other concerns

Prior to the deployment there was some controversy in that the Government had not resolved the situation with regard to repatriation cover or peacekeeping force cover with respect to the Veterans' Entitlements Act and had also not made a declaration of whether there would be a declaration of operational service or not. The issues of pay and allowances were resolved but many other conditions of service type issues were identified but not resolved.[36]

During the deployment there were very few issues, one issue that was raised in parliament related to censorship of mail.[124] The families of soldiers deployed on the second contingent had the benefit of a full-time welfare officer who was based in Australia. The officer's sole task was the provision of welfare support to the families of the deployed force.[72]

After the deployment, the issues of appropriate service conditions, awards and recognition took many years to resolve. After serving the required 90 day period, the contingent members became entitled to the Australian Service Medal (ASM) for non-warlike service. Some 12 years after their return to Australia, the Government changed the status of the operation and the contingent members became eligible for the Returned from Active Service Badge and were upgraded from the ASM to the Australian Active Service Medal (AASM).[125][126] In 2002 following this decision Major Nigel Catchlove wrote to the Army Newspaper and compared the UNTAG operation to two other subsequent operations: Operation Solace being the 1st Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (1RAR) battalion group in Somalia and the service personnel who served with the International Force for East Timor. He said that both of those operations involved robust rules of engagement appropriate to the intervention of forces in UN-sanctioned, US or Australian-led multi-national coalitions. UNTAG by way of contrast was a classic peacekeeping operation led by the UN in a relatively benign environment where rules of engagement were focused only on force protection. Catchlove also questioned the half-hearted approach to implementing this appaling decision in which eligible people must apply for the upgrade and said that this failed the test of commonsense.[127]

Timeline of Australian involvement in Namibia

A timeline of key dates is presented in the following table:[128][129]

| 1979 |

|

| August 1988 |

|

| September 1988 |

|

| February 1989 | |

| March 1989 | |

| April 1989 |

|

| May 1989 |

|

| June 1989 |

|

| July 1989 |

|

| September 1989 |

|

| October 1989 |

|

| November 1989 |

|

| February 1990 |

|

| April 1990 |

|

References

- Footnotes

- ^ Sitkowski noted that this was a political compromise, because the South African administration was considered illegal.[50]

- ^ Gration, the Chief of the Defence Force at the time issued two directives in the first week of March, one to the Chief of the General Staff (CDF Directive 1/1989), ordering him to provide an engineer force to Namibia in an operation to be known as Operation Picaresque. The second directive (CDF 2/1989) was to Colonel Warren, appointing him commander of the Australian Contingent, a 'national command appointment' in which he was to report directly to the CDF on matters relating to national policy.[60]

- ^ In the Official History Horner notes that the South Africans claimed that the Koevoet killed 294 insurgents and captured 14, while the SADF and SWATF killed another eighteen and captured twenty six. The police lost twenty killed and the SADF five.[81]

- ^ Horner notes that the commendation was held in trust by the 17th Construction Squadron but was destroyed in a fire, fortunately copies had been made.[109]

- Citations

- ^ a b c Horner 2011, p. 53.

- ^ Crocker 1991, p. 7.

- ^ Horner 2011, p. 137.

- ^ Sitkowski 2006, p. 84.

- ^ Mays, Terry (2011). Historical Dictionary of Multinational Peacekeeping. United Kingdom: Scarecrow Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-8108-6808-3. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ^ Tsokodayi, Cleophas. Namibia's Independence Struggle; The Role of the United Nations. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 978-1-4568-5291-7. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ Thornberry 2004, p. 9.

- ^ Huphreys, Ben (1989). Digest of Bill. Australian Government. p. 1.

- ^ Petronella Sibeene (17 April 2009). "Swapo Party Turns 49". New Era.

- ^ Thornberry 2004, p. 26.

- ^ Thornberry 2004, p. 344.

- ^ Gleijeses, Piero (11 July 2007). "Cuito Cuanavale revisited". Mail & Guardian.

- ^ "UN council condemnds S. Africa on Angola". Chicago Sun-Times. 26 November 1987.

- ^ Sowry 1992, p. 9.

- ^ Horner 2011, pp. 70–71.

- ^ "Resolution 2145". Resolution. United Nations. 27 October 1966. p. 3. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ "Resolution 264" (PDF). Resolution. United Nations. 20 March 1969. p. 3. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ "Resolution 435" (PDF). Resolution. United Nations. 29 September 1978. p. 3. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Wellens, Karen (1990). Resolutions and Statements of the United Nations Security Council (1946–1989): A Thematic Guide. BRILL. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-7923-0796-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Namibia – UNTAG Mandate". Website. United Nations. X. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Resolution 632" (PDF). Resolution. United Nations. 16 February 1989. p. 3. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ a b Horner 2011, p. 55.

- ^ Gough Whitlan, Member for Werriwa (11 April 1961). http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id%3A%22hansard80%2Fhansardr80%2F1961-04-11%2F0137%22. Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Commonwealth of Australia: House of Representatives.

{{cite book}}:|chapter-url=missing title (help) - ^ Horner 2011, p. 56.

- ^ Horner 2011, p. 58.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bob Hawke, Prime Minister (6 March 1989). http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id%3A%22chamber%2Fhansardr%2F1989-03-06%2F0025%22. Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Commonwealth of Australia: House of Representatives.

{{cite book}}:|chapter-url=missing title (help) - ^ Horner 2011, p. 59.

- ^ Sir Jim Killen (17 October 1985). "Fraser ... the force that stalks Australian politics". Killen: Inside Australian Politics. Methuen Haynes. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Horner 2011, p. 62.

- ^ Horner 2011, p. 63.

- ^ a b c Horner 2011, p. 64.

- ^ "Rt Hon Malcolm Fraser AC". CEDA Board of Governors. Committee for Economic Development of Australia. 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ "Fraser, John Malcolm" (PDF). The University of Melbourne Archives. The University of Melbourne. 1968–1980. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ a b Horner 2011, p. 45.

- ^ Horner 2011, p. 54.

- ^ a b Tim Fischer, Member for Farrer (6 March 1989). http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id%3A%22chamber%2Fhansardr%2F1989-03-06%2F0060%22. Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Commonwealth of Australia: House of Representatives.

{{cite book}}:|chapter-url=missing title (help) - ^ Gareth Evans (16 August 1991). http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id%3A%22chamber%2Fhansards%2F1991-08-16%2F0070%22. Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Commonwealth of Australia: Senate.

{{cite book}}:|chapter-url=missing title (help) - ^ Dr Blewett, Member for Bonython (15 April 1991). http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id%3A%22chamber%2Fhansardr%2F1991-04-15%2F0085%22. Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Commonwealth of Australia: House of Representatives.

{{cite book}}:|chapter-url=missing title (help) - ^ Horner 2011, p. 143.

- ^ Condell, Diana (10 November 2003). "Obituary: Lieut Gen Dewan Prem Chand, General at the sharp end of UN peacekeeping operations". The Guardian.

- ^ a b John Sampson (29 March 1989). "Soldiers restricted for their own safety". Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^ Warren, Richard (1 November 1989). Australian Contingent UNTAG: The Initial Involvement (PDF) (Speech). RUSI. Joint Services Staff College. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Crocker 1991, p. 6.

- ^ a b Cameron Forbes (9 November 1989). "In Namibia, the war never really goes away". The Age.

- ^ Crocker, J.A.; Warren, R.D (1985). "Technology in Developing Countries ; A Military Perspective". National Engineering Conference: The Community and Technology Growing Together Through Engineering. Barton, Australian Capital Territory: Institution of Engineers, Australia: 449, 452. ISBN 0-85825-274-0.

- ^ Commonwealth of Australia, Parliamentary Debates, House of Representatives, 6 March 1989, (Hon. Roslyn Kelly, Minister for Defence Science and Personnel).

- ^ a b Arlene Getz (3 April 1989). "Australian troops get a surprise in Namibia". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ a b Speech by the Prime Minister: Australia's Contingent to Namibia, Holsworthy 5 April 1989 (Speech). Farewell Parade. Holsworthy Barracks: Prime Minister of Australia. 5 April 1989. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ Horner 2011, p. 102.

- ^ Sitkowski 2006, p. 79.

- ^ Sowry 1992, p. 1.

- ^ Thornberry 2004, p. 172.

- ^ Fomerand, Jacques (2007). Historical Dictionary of the United Nations (PDF). Historical Dictionaries of International Organizations, No. 25. The Scarecrow Press. p. xxiii. ISBN 978-0-8108-5494-9.

- ^ Thornberry 2004, p. 162.

- ^ Sowry 1992, p. 10.

- ^ Sowry 1992, p. 18.

- ^ Horner 2011, pp. 77–78.

- ^ a b c Horner 2011, p. 120.

- ^ Sawer 2001, p. 176.

- ^ a b c d Horner 2011, p. 80.

- ^ a b Horner 2011, p. 66.

- ^ Horner 2011, p. 67.

- ^ Horner 2011, p. 68.

- ^ Horner 2011, p. 69.

- ^ a b Horner 2011, p. 75.

- ^ Horner 2011, p. 76.

- ^ a b c d Horner 2011, p. 77.

- ^ a b c Horner 2011, p. 78.

- ^ Senator Vallentine, Senator for Western Australia (29 May 1991). http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id%3A%22chamber%2Fhansards%2F1991-05-29%2F0158%22. Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Commonwealth of Australia: Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade.

{{cite book}}:|chapter-url=missing title (help) - ^ Senator Newman, Senator for Tasmania (23 May 1989). http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id%3A%22chamber%2Fhansards%2F1989-05-23%2F0120%22. Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Commonwealth of Australia: Senate.

{{cite book}}:|chapter-url=missing title (help) - ^ "Australia to send troops to Namibia". The Canberra Times. Canberra. 3 March 1989. p. 4.

- ^ a b Sowry 1992, p. 46.

- ^ Horner 2011, p. 79.

- ^ Horner 2011, p. 84.

- ^ a b Horner 2011, p. 85.

- ^ a b Horner 2011, p. 100.

- ^ Horner 2011, p. 89.

- ^ Hearn 1999, p. 101.

- ^ Sitkowski 2006, p. 82.

- ^ Horner 2011, p. 88.

- ^ a b Horner 2011, p. 91.

- ^ Hearn 1999, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Wren, Christopher (19 April 1989). "U.N. Guards Rebels at Namibia Border". The New York Times.

- ^ "Ceasefire call beamed into Namibian bush". The Age. 11 April 1989.

- ^ a b c Horner 2011, p. 94.

- ^ Horner 2011, p. 96.

- ^ Horner 2011, p. 99.

- ^ a b c "UNTAG". United Nations Missions. United Nations. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ "Chronology". Dr Klaus Dierks. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Getz 1989, pp. 49–52.

- ^ a b c d e Horner 2011, p. 133.

- ^ Horner 2011, p. 107.

- ^ Horner 2011, p. 109.

- ^ Tim Fischer, Member for Farrer (4 October 1989). http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id%3A%22chamber%2Fhansardr%2F1989-10-04%2F0105%22. Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Commonwealth of Australia: House of Representatives.

{{cite book}}:|chapter-url=missing title (help) - ^ Horner 2011, p. 119.

- ^ Horner 2011, p. 122.

- ^ Horner 2011, p. 123.

- ^ Sowry 1992, p. 36.

- ^ Horner 2011, p. 124.

- ^ a b c Horner 2011, p. 125.

- ^ Thornberry 2004, p. 322.

- ^ Horner 2011, p. 134.

- ^ Horner 2011, p. 140.

- ^ Horner 2011, p. 141.

- ^ Senator Graham Richardson (26 May 1989). http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id%3A%22chamber%2Fhansards%2F1989-05-26%2F0167%22. Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Commonwealth of Australia: Senate.

{{cite book}}:|chapter-url=missing title (help) - ^ The Norwegian Nobel Committee (29 September 1988). "The Nobel Peace Prize 1988". Oslo: Nobel Prize. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ Javier Pérez de Cuéllar (9 January 1989). "Nobel Lecture 1989". Oslo: Nobel Prize. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ "Commendation, Australian Contingent UNTAG". Army Headquarters, Canberra. 2 March 1990.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Horner 2011, p. 142.

- ^ Administration of Australian Battle Honours, Theatre Honours, Honour Titles and Honour Distinctions. Defence Instruction (Army). Vol. 38–3 (ADMIN ed.). Canberra: Australian Army. 4 May 2012.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ a b "Letter from the Chief of Army to the Governor General". Army Headquarters, Canberra. 10 April 2012: 2. OCA/OUT/2012/R11194182.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Horner 2011, p. 129.

- ^ Horner 2011, p. 86.

- ^ Sowry 1992, p. 32.

- ^ Thornberry 2004, p. 118.

- ^ Thornberry 2004, p. 151.

- ^ Horner 2011, p. 106.

- ^ Sowry 1992, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Younghusband, Peter (18 March 1989). "Our Troops in Namibia row; South Africans claim election bias". The Weekend Australian. Sydney. p. 1.

- ^ Horner 2011, p. 87.

- ^ Horner 2011, p. 112.

- ^ Horner 2011, p. 93.

- ^ "Soldiers in Namibia down with malaria". The Canberra Times. Canberra. 9 July 1989.

- ^ Robert Tickner, Member for Hughes (17 August 1989). http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id%3A%22chamber%2Fhansardr%2F1989-08-17%2F0283%22. Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Commonwealth of Australia: House of Representatives.

{{cite book}}:|chapter-url=missing title (help) - ^ "Gazette No. S 303, Upgraded from ASM CAG S303 dated 26 Jul 01" (PDF). Special Gazette. Commonwealth of Australia. 26 July 2001. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ "Australian Active Service Medal". Defence Honours & Awards. Commonwealth of Australia. 19 January 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ Catchlove, Nigel (4 July 2002). "Service in Namibia only needs an ASM". Letters to the Editor. Army, The Soldiers' Newspaper. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ Horner 2011, pp. 53–143.

- ^ Sowry 1992, pp. 3–4.

- Sources

- Crocker, John (1991), "Multinational Peacekeeping" (PDF), Australian Defence Force Journal (86), Letter to the Editor: Australian Defence Force: 6–7, retrieved 29 July 2012

{{citation}}: More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Arlene Getz (5 August 1989), Shelley Gare (ed.), "Join the Army: See Namibia", Good Weekend, The Sydney Morning Herald: John Fairfax Group: 49–52

{{citation}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - Hearn, Roger (1999), UN Peacekeeping in Action: The Namibian Experience, Commack, New York: Nova Science Publishers, p. 272, ISBN 1-56072-653-9, retrieved 29 July 2012

{{citation}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - Horner, David (2011), "Australia and the New World Order: The Official History of Australian Peacekeeping, Humanitarian and Post-Cold War Operations", From Peacekeeping to Peace Enforcement: 1988–1991, vol. 2, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-76587-9, retrieved 29 July 2012

- Sawer, Marian (2001), Elections: Full, Free & Fair, Federation Press, p. 176, retrieved 31 July 2012

- Sitkowski, Andrzej (2006), UN Peacekeeping: Myth and Reality, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-275-99214-9, retrieved 1 August 2012

- Sowry, Brendan, ed. (1992), "United Nations Transition Assistance Group (UNTAG) in Namibia", Training Information Bulletin Number 63, no. Draft, Australian Army

{{citation}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Thornberry, Cedric (2004), A Nation Is Born: The Inside Story of Namibia's Independence, Gamsberg Macmillan Publishers, pp. 9–11, ISBN 978-99916-0-521-0

{{citation}}: More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help)

External links

![]() Media related to Australian contribution to United Nations Transition Assistance Group at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Australian contribution to United Nations Transition Assistance Group at Wikimedia Commons

- Use dmy dates from September 2012

- Military history of Australia

- Foreign relations of Australia

- Political history of Australia

- Military operations involving Australia

- Military operations involving New Zealand

- History of Australia since 1945

- Military units and formations established in 1989

- Military engineering