Forth Bridge

Forth Bridge | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates | 56°00′02″N 3°23′19″W / 56.000421°N 3.388726°W |

| Carries | Rail traffic |

| Crosses | Firth of Forth |

| Locale | Edinburgh, Inchgarvie and Fife, Scotland |

| Maintained by | Balfour Beatty under contract to Network Rail |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Cantilever bridge |

| Total length | 2,528.7 m (8,296 ft) |

| Longest span | 2 of 521.3 m (1710 ft) |

| Clearance below | 46 metres (151 ft) |

| History | |

| Designer | Sir John Fowler and Sir Benjamin Baker |

| Opened | 4 March 1890 |

| Statistics | |

| Daily traffic | 190–200 trains per day |

| Location | |

| |

The Forth Bridge is a cantilever railway bridge over the Firth of Forth in the east of Scotland, to the east of the Forth Road Bridge, and 14 kilometres (9 mi) west of central Edinburgh. It was opened on 4 March 1890, and spans a total length of 2,528.7 metres (8,296 ft). It is often called the Forth Rail Bridge or Forth Railway Bridge to distinguish it from the Forth Road Bridge, although it has been called the "Forth Bridge" since its construction, and was for over seventy years the sole claimant to this name.

The bridge connects Scotland's capital city, Edinburgh, with Fife, leaving the Lothians at Dalmeny and arriving in Fife at North Queensferry; it acts as a major artery connecting the north-east and south-east of the country. Described by the Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland as "the one immediately and internationally recognised Scottish landmark",[1] it is a Category A listed building[2][3] and was nominated by the British government in May 2011 for addition to the UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Scotland.[4]

The bridge was begun in 1883, took 7 years to complete, cost the lives of 98 [5] men and nearly 58,000 tonnes (128,000,000 lb) of metal [6] and used 10 times as much metal as the Eiffel Tower. It was deliberately chosen to look strong, due to the collapse 4 years earlier of the first Tay Bridge.[7]

Until 1917, when the Quebec Bridge was completed, the Forth Bridge had the longest single cantilever bridge span in the world. It still has the world's second-longest single span.[8][9] The bridge and its associated railway infrastructure is owned by Network Rail Infrastructure Limited.

History

Construction of an earlier bridge, a suspension bridge designed by Sir Thomas Bouch, got as far as the laying of the foundation stone, but was stopped after the collapse of another of his works, the Tay Bridge. The public inquiry into the Tay bridge disaster declared the Tay Bridge "poorly designed, poorly constructed and poorly maintained".[10] Bouch was disgraced, and the project was subsequently taken over by Sir John Fowler and Sir Benjamin Baker: who designed a structure that was built by Glasgow based company Sir William Arrol & Co. between 1883 and 1890. Allan Stewart was resident engineer.

First steel structure in United Kingdom

The bridge was the first major structure in Britain to be constructed of steel;[11] its contemporary, the Eiffel Tower was built of wrought iron.

Large amounts of steel had become available only after the invention of the Bessemer process in 1855. Until 1877 the British Board of Trade had limited the use of steel in structural engineering because the process produced steel of unpredictable strength. Only the Siemens-Martin open-hearth process developed by 1875 yielded steel of consistent quality. The 64,800 tons[clarification needed] of steel needed for the bridge was provided by two steel works in Scotland and one in Wales.[12]

Construction

The bridge is, even today, regarded as an engineering marvel.[13] It is 2.5 kilometres (1.6 mi) in length, and the double track is elevated 46 metres (151 ft) above the water level at high tide. It consists of two main spans of 521.3 metres (1,710 ft), two side spans of 207.3 metres (680 ft), and 15 approach spans of 51.2 metres (168 ft).[14] Each main span comprises two 207.3 metres (680 ft) cantilever arms supporting a central 106.7 metres (350 ft) span truss. The weight of the bridge superstructure was 51,324 tonnes (50,513 long tons), including the 6.5 million rivets used.[14] The bridge also used 18,122 cubic metres (640,000 cu ft) of granite.[15]

The three great four-tower cantilever structures are 100.6 metres (330 ft) tall,[14] each tower resting on a separate granite pier. These were constructed using 21 metres (70 ft) diameter caissons, those for the north cantilever and two on Inchgarvie acting as coffer dams while the remaining two on Inchgarvie and those for the south cantilever, where the river bed was 28 m (91 ft) below high-water level used compressed air to keep water out of the working chamber at the base.[16]

At its peak, approximately 4,600 workers were employed in its construction. Initially, it was recorded that 57 lives were lost; however, after extensive research by local historians, the figure was increased to 63.[17] Eight men were saved from drowning by boats positioned in the river under the working areas. Hundreds of workers were left crippled by serious accidents, and one log book of accidents and sickness had 26,000 entries. In 2005, a project was set up by the Queensferry History Group to establish a memorial to those workers who died during the bridge's construction. In North Queensferry, a decision was also made to set up memorial benches to commemorate those who died during the construction of both the rail and the road bridges, and to seek support for this project from Fife Council.[citation needed]

Work at the site began at the end of 1882, with the construction at South Queensferry of the extensive workshops where the steelwork was to be fabricated. These eventually occupied more than 50 acres. Work on the foundations of the bridge began in February 1883, and the first of the caissons was launched on 26 May 1884. The bridge was completed in December 1889, and load testing of the completed bridge was carried out on 21 January 1890. Two trains, each consisting of three heavy locomotives and 50 wagons loaded with coal, totalling 1,880 tons in weight, were driven slowly from South Queensferry to the middle of the north cantilever, stopping frequently to measure the deflection of the bridge. This represented more than twice the design load of the bridge: the deflection under load was as expected.[16] A few days previously there had been a violent storm, producing the highest wind pressure recorded to date at Inchgarvie, and the deflection of the cantilevers had been less than 25 mm (1 in). The first complete crossing took place on 24 February, when a train consisting of two carriages carrying the chairmen of the various railway companies involved made several crossings. The bridge was opened on 4 March 1890 by the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII, who drove home the last rivet, which was gold plated and suitably inscribed.[15] The key for the official opening was made by Edinburgh silversmith John Finlayson Bain, commemorated in a plaque on the bridge.

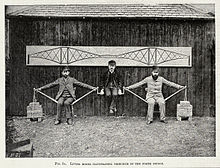

The use of a cantilever in bridge design was not a new idea, but the scale of Baker's undertaking was unprecedented. Much of the work done was without precedent, including calculations for incidence of erection stresses (the internal forces exerted on structural members during construction), provisions made for reducing future maintenance costs, calculations for wind pressures made evident by the Tay Bridge disaster and the effect of temperature stresses on the structure.

Where possible, the bridge used natural features such as Inchgarvie, an island, the promontories on either side of the firth at this point, and also the high banks on either side.

The bridge has a speed limit of 50 miles per hour (80 km/h) for passenger trains and 20 miles per hour (32 km/h) for freight trains. The weight limit for any train on the bridge is 1,422 tonnes (1,400 long tons; 1,567 short tons) although this was waived for the frequent coal trains which used the bridge prior to the reopening of the Stirling-Alloa-Kincardine railway, provided two such trains did not simultaneously occupy the bridge. The route availability code is RA8, meaning any current UK locomotive can use the bridge, which was designed to accommodate heavier steam locomotives.

Up to 190–200 trains per day crossed the bridge in 2006.[18]

Ownership

Prior to the opening of the bridge, the North British Railway (NBR) had lines on both sides of the Firth of Forth between which trains could not pass except by running at least as far west as Alloa and using the lines of a rival company. The only alternative route between Edinburgh and Fife involved the ferry at Queensferry, which was purchased by the NBR in 1867. Accordingly, the NBR sponsored the Forth Bridge project which would give them a direct link independent of the Caledonian Railway;[19] a conference at York in 1881 set up the Forth Bridge Railway Committee, to which the NBR contributed 35% of the cost. The remaining money came from three English railways, who ran trains from London over NBR tracks: the Midland Railway, to which the NBR connected at Carlisle and which owned the route to London (St Pancras), contributed 30%, whilst the remainder came equally from the North Eastern Railway and the Great Northern Railway, who between them owned the route between Berwick-upon-Tweed and London (King's Cross), via Doncaster. This body undertook to construct and maintain the bridge.[20] In 1882 the NBR were given powers to purchase the bridge, which it never exercised.[19] At the time of the 1923 Grouping, the bridge was still jointly owned by the same four railways,[21][22] and so it became jointly owned by these companies' successors, the London Midland and Scottish Railway (30%) and the London and North Eastern Railway (70%).[23] The Forth Bridge Railway Company was named in the Transport Act 1947 as one of the bodies to be nationalised and so became part of British Railways on 1 January 1948.[24] Under the Act, Forth Bridge shareholders would receive £109 of British Transport stock for each £100 of Forth Bridge Debenture stock; and £104-17-6d (£104.87½) of British Transport stock for each £100 of Forth Bridge Ordinary stock.[25][26]

Maintenance

A structure like the Forth Bridge needs constant maintenance and the ancillary works for the bridge included not only a maintenance workshop and yard but a railway "colony" of some fifty houses at Dalmeny Station. The track on the bridge is of "waybeam" construction: 12 inch square baulks of timber 6 metres long are bolted into steel troughs in the bridge deck and the rails are fixed on top of these sleepers. In 1992 the bridge was re-railed with standard BS113A rail (54 kg/m).[citation needed] Prior to 1992 the rails on the bridge were of a unique "Forth Bridge" section.

Although modern trains put fewer stresses on the bridge than the earlier steam trains, the bridge needs constant maintenance, and this is currently undertaken by Balfour Beatty under contract to Network Rail.[27]

"Painting the Forth Bridge" is a colloquial expression for a never-ending task, coined on the erroneous belief that at one time in the history of the bridge repainting was required and commenced immediately upon completion of the previous repaint.[28] According to a 2004 New Civil Engineer report on modern maintenance, such a practice never existed, although under British Rail management, and before, the bridge had a permanent maintenance crew.

A recent repainting of the bridge commenced with a contract award in 2002, for a schedule of work which was completed on 9 December 2011.[29] It involved the application of 230,000 m2 of paint at a total cost of £130M. This new coat of paint is expected to have a life of at least 25 years, and perhaps as long as 40 years.[30] The work involved blasting all previous layers of paint off the bridge for the first time in its history, allowing repairs to be made to the steel.[30][31][32]

In a report produced by JE Jacobs, Grant Thornton and Faber Maunsell in 2007 which reviewed the alternative options for a second road crossing, it was stated that "Network Rail has estimated the life of the bridge to be in excess of 100 years. However, this is dependant [sic] upon NR’s inspection and refurbishment works programme for the bridge being carried out year on year".[33]

Competition

In 2007, in a two-week trial jointly funded by SEStran and StageCoach, a passenger hovercraft ran between Kirkcaldy and Edinburgh,[dead link][34] but Stagecoach have indicated that they are not interested in developing this into a service.[35]

The new Stirling-Alloa-Kincardine rail link will divert coal trains away from the bridge. Instead they will travel via Stirling to Longannet Power Station. Freight restrictions may then be lifted, with the potential of increasing the number of trains from 10 tph (trains per hour) to 12.

World Wars

In the First World War returning British sailors would time their departures or returns to the base at Rosyth by asking when they would pass under the bridge.[36] This practice continued at least up to the 1990s.

The bridge featured in the background to one of popular marine artist W.L. Wylie's painting's of British capital ships in action during the Great War. His "The Wounded Lion" depicts the flagship of Vice-Admiral Sir David Beatty's First Battle-Cruiser Squadron being towed home by HMS Indomitable after being badly damaged at the Battle of Dogger Bank, in January 1915. HMS Lion was almost lying on her beam ends by the time she reached Rosyth. 15 years later, one of her adversaries at Dogger Bank, the German battle-cruiser Moltke, achieved the unique status of passing under the centre span of the bridge "upside down and out-of-control" after breaking free of her tugs on the final leg of being towed for breaking-up at Inverkeithing.

The first German air attack on Britain of the Second World War took place over the Forth Bridge, six weeks into the war, on 16 October 1939. Although known as the "Forth Bridge Raid", the bridge was not the target and not damaged. In all, 12 German Junkers Ju 88 bombers led by two reconnaissance Heinkel He 111s from Westerland on the island of Sylt, 460 miles away, reached the Scottish coast in four waves of three.[37] The target of the attack was shipping from the Rosyth naval base in the Forth Estuary, close to the bridge. The Germans were hoping to find HMS Hood, the largest capital ship in the Royal Navy. At this time, the Luftwaffe's rules of engagement restricted action to targets on water and not in the dockyard. Although HMS Repulse was in Rosyth, the attack was concentrated on cruisers HMS Edinburgh and HMS Southampton, carrier HMS Furious and destroyer HMS Jervis.[38] Southampton and Edinburgh sustained minor damage and a combined total of ten injuries but no deaths. Spitfires from RAF 603 "City of Edinburgh" squadron intercepted the raiders and during the attack shot down the first German planes downed over Britain in the war.[39] One bomber came down in the water off Port Seton on the East Lothian coast, another off Crail on the coast of Fife. After the war it was learned that a third bomber had come down in Holland as a result of damage inflicted in the raid. Later in the month, a reconnaissance Heinkel 111 crashed near Humbie in East Lothian and photographs of this crashed plane were, and still are, used erroneously to illustrate the raid of 16 October, thus sowing confusion as to whether a third plane had been brought down.[40] Members of the bomber crew at Port Seton were rescued and made prisoners-of-war. Two bodies were recovered from the Crail wreckage and, after a full military funeral with firing party, were interred in Portobello cemetery, Edinburgh. The body of the gunner was never found.[41]

Banknotes, coins

A representation of the Forth Bridge appears on the 2004 Issue one pound coin.[42]

The 2007 series of banknotes issued by the Bank of Scotland depicts different bridges in Scotland as examples of Scottish engineering, and the £20 note features the Forth Bridge.[43]

Popular culture

- There is a scene on the bridge in Alfred Hitchcock's 1935 film The 39 Steps and it is featured even more prominently in the 1959 remake of the same film, although there is no reference to the bridge in the book by John Buchan upon which the films are based.

- The bridge featured in posters advertising the soft drink Barr's Irn Bru, with the slogan: Made in Scotland, from girders

- The bridge was lit up red for BBC's Comic Relief in 2005.

- A countdown clock to the millennium was placed on the bridge in 1998.

- The Bridge, a novel by Iain Banks, is mainly set on a fictionalised version of the bridge.

- In Alan Turing's most famous paper about artificial intelligence, one of the challenges put to the subject of an imagined Turing test is "Please write me a sonnet on the subject of the Forth Bridge". The test subject in Turing's paper answers, "Count me out on this one. I never could write poetry".[44]

- Sébastien Foucan, a French freerunner, crawled along one of the highest points of the bridge, without a harness, for the Jump Britain documentary made by Channel 4.

- Linus points out the bridge from the airplane in the 1980 Peanuts film, Bon Voyage, Charlie Brown (And Don't Come Back!!) as they approached Heathrow Airport. The Forth Bridge is 273 nautical miles (506 km) north of Heathrow, and is often visible on the approach to Edinburgh Airport.

- The bridge is included in the video game Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas by Edinburgh-based developer Rockstar North. Renamed the Kincaid Bridge, it serves as the main railway bridge of the fictional city of San Fierro, and appears alongside a virtual Forth Road Bridge.[45]

- The bridge inspired the design of the "Tubeline Bridge" which connects Route 8 with Route 9 in the Pokémon Black and White video games.[46]

References

- ^ Keay, John; Keay, Julie (2000). Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland. London: HarperCollins. p. 409. ISBN 0-00-255082-2.

- ^ "Historic Scotland listing entry (City of Edinburgh)". Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ^ "Historic Scotland listing entry (Fife)". Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ^ "UNESCO World Heritage Centre tentative list: Forth Bridge". Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ BBC News - Rail bridge death toll increases Template:En ikon

- ^ Forth Rail Bridge at Structurae Template:En ikon

- ^ http://www.wild-in-scotland.com/forthbridges.php

- ^ DeLony, Eric (1996). "Context for World Heritage Bridges". Paris: International Council on Monuments and Sites. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ^ "Forth Rail Bridge facts and figures". Forth Bridges Visitors Centre Trust. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ^ "The Tay Bridge Disaster". The Times (29925). London: 5. 5 July 1880.

- ^ Plank, Roger; McEvoy, Michael; Steel Construction Institute (1993). "Forth Railway Bridge: First steel structure". Architecture and Construction in Steel (illustrated ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 16. ISBN 0-419-17660-8.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help);|format=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Langmead, Donald; Garnaut, Christine (2001). Encyclopedia of Architectural and Engineering Feats (Google Books) (3 ed.). ABC-CLIO. p. 119. ISBN 1-57607-112-X. Retrieved 2009-03-06.

- ^ "Overview of Forth Bridge". Scottish-places.info. Retrieved 2012-05-11.

- ^ a b c "Forth Rail Bridge Facts & Figures". Forth Bridges Visitors Centre Trust. Retrieved April 21, 2006.

- ^ a b Overview of Forth Bridge. The Gazetteer for Scotland. Retrieved 21 April 2006

- ^ a b "Description and History of the Bridge". The Times. No. 32950. London. Tuesday 4 March 1890. p. 13.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "The Men Who Died Building the Forth Bridge". Forth Bridges isitor Centre Trust. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ "The Forth Bridge". Forth Bridges Visitors Centre Trust. Retrieved 21 April 2006.

- ^ a b Awdry, Christopher (1990). Encyclopaedia of British Railway Companies. London: Guild Publishing. p. 132. CN 8983.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Thomas, John; Turnock, David (1989). Thomas, David St John; Patmore, J. Allan (eds.). A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: Volume XV — North of Scotland. Newton Abbot: David St John Thomas. p. 71. ISBN 0-946537-03-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Conolly, W. Philip (1976). British Railways Pre-Grouping Atlas and Gazetteer (5th ed.). Shepperton: Ian Allan. p. 49. ISBN 0-7110-0320-3. EX/0176.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Whitehouse, Patrick; Thomas, David St John (1989). LNER 150: The London and North Eastern Railway — A Century and a Half of Progress. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. p. 21. ISBN 0-7153-9332-4. 01LN01.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Hughes, Geoffrey (1987) [1986]. LNER. London: Guild Publishing/Book Club Associates. pp. 33–34. CN 1455.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ His Majesty's Government (6 August 1947). "Transport Act 1947 (10 & 11 Geo. 6 ch. 49)" (PDF). London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. p. 145. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

{{cite web}}:|chapter=ignored (help) - ^ Transport Act 1947, fourth schedule, p. 148

- ^ Bonavia, Michael R. (1981). British Rail: The First 25 Years. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. p. 10. ISBN 0-7153-8002-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ "Balfour Beatty Awarded Forth Bridge Contract". Press Release. Balfour Beatty, 28 April 2002. Retrieved 21 April 2006.

- ^ "be like painting the Forth Bridge". theFreeDictionary.com. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- ^ "Forth Bridge painting completed'". BBC News. 9 December 2011. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- ^ a b Cramb, Auslan (18 February 2008). "Non-stop job of painting Forth Bridge to end". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

- ^ McKenna, John (19 February 2008). "Painting of Forth bridge to end". New Civil Engineer. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

- ^ "Rail bridge shuts for repair". BBC News. 4 July 2003. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

- ^ "Forth Replacement Crossing - Report 1 - Assessment of Transport Network". Transport Scotland. Retrieved 2012-05-11.

- ^ http://www.stagecoachbus.com/fife/forthfastinfo.html[dead link]

- ^ "Press Release Articles from". SEStran. 2008-02-19. Retrieved 2012-05-11.

- ^ A North Sea Diary 1914-1918, p. 80

- ^ W. Simpson, Spitfires Over Scotland, G C Books Ltd., 2010 ISBN 978 187 25 0448, p.84

- ^ W. Simpson, Spitfires Over Scotland, p.92

- ^ "Air attack in the Firth of Forth - World War II (1939-45) - Scotlands History". Ltscotland.org.uk. 1939-10-16. Retrieved 2012-05-11.

- ^ W. Simpson, Spitfires Over Scotland, p.108

- ^ W. Simpson, Spitfires Over Scotland, p.100 & p.109

- ^ "The United Kingdom £1 Coin". The Royal Mint. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ "Current Banknotes : Bank of Scotland". The Committee of Scottish Clearing Bankers. Retrieved 2008-10-29.

- ^ Turing, Alan (October 1950), "Computing Machinery and Intelligence", Mind, LIX (236): 433–460, doi:10.1093/mind/LIX.236.433, ISSN 0026-4423

- ^ "Grand Theft Auto Wiki — Kincaid Bridge".

- ^ "Bulbapedia — Tubline Bridge".

Further reading

- Koerte, Arnold, Firth of Forth, Firth of Tay, Birkhauser Verlag (1992), ISBN 0-8176-2444-9

- New Civil Engineer (5 February 2004), page 18.

- Lewis, Peter R., Beautiful Railway Bridge of the Silvery Tay: Reinvestigating the Tay Bridge Disaster of 1879. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Tempus Publishing (2004), ISBN 0-7524-3160-9.

- McKean, Charles, Battle for the North: The Tay and Forth Bridges and the 19th Century Railway Wars, Granta Books (7 August 2006), ISBN 1-86207-852-1

- Norrie, Charles Matthew, Bridging the Years — a short history of British Civil Engineering. Edward Arnold Ltd (1956)

- Rolt, L.T.C., Victorian Engineers. London: Pelican Books (1974)

- Wills, Elspeth, The Briggers — The Story of the Men who built the Forth Bridge, Birlinn (2009), ISBN-978-1-84158-781-5.

External links

- Forth Bridges Visitor Centre Trust - Rail Bridge Main

- Forth Bridge Memorial

- Forth Rail Bridge at Structurae

- Poetry Map of Scotland Firth of Forth: "Construction of the Forth Bridge"

- Clarence Winchester, ed (1935), "The Forth Bridge", Railway Wonders of the World, pp. 432–441

{{citation}}:|author=has generic name (help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)