Nuclear weapons of the United Kingdom

| United Kingdom | |

|---|---|

| Nuclear program start date | October 21, 1939 |

| First nuclear weapon test | October 2, 1952 |

| First thermonuclear weapon test | May 15, 1957 |

| Last nuclear test | November 26, 1991 |

| Largest yield test | 3 Mt (April 28, 1958) |

| Total tests | 45 detonations |

| Peak stockpile | 350 warheads (1970s) |

| Current stockpile | c. 200 warheads |

| Maximum missile range | 12,000 km/7,500 mi (sub) |

| Nuclear weapons |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Nuclear-armed states |

|

The United Kingdom was the third country to test an independently developed nuclear weapon in October 1952. It is one of the five "Nuclear Weapons States" (NWS) under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, which the UK ratified in 1968. The UK is currently thought to retain a weapons stockpile of around 200 nuclear warheads.

Since the 1958 US-UK Mutual Defence Agreement, the US and UK have cooperated extensively on nuclear security matters. The so-called special relationship between the two countries has involved the exchange of classified scientific information and nuclear materials such as plutonium. Britain has not run an independent weapon development programme since the failure of the Blue Streak missile in the 1960s, instead buying American delivery systems and fitting them with British-manufactured warheads. Throughout and beyond the cold war, the UK has relied on US-controlled early warning systems for the detection of a ballistic missile attack.

In contrast with the other permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, the United Kingdom currently has operated only a single nuclear deterrent since decommissioning its free-falling nuclear bombs in 1998. This system consists of four Vanguard class submarines armed with nuclear-tipped Trident missiles, performing both the strategic and sub-strategic roles. An official decision on the replacement of Trident, which was developed during the cold war, is expected in the next few years, although it has been reported that preparations are already underway.[1]

Number of warheads

In the Strategic Defence Review published in July 1998, the British Government stated that once the Vanguard submarines became fully operational (the fourth and final one, Vengeance, entered service on 27 November 1999), it would "maintain a stockpile of fewer than 200 operationally available warheads" [2]. The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute has estimated the figure as about 185, consisting of 160 deployed weapons plus an extra 15 percent as spares[3].

At the same time, the British Government indicated that warheads "required to provide a necessary processing margin and for technical surveillance purposes" were not included in the "fewer than 200" figure.[4] Many estimates for the total number of warheads are around 200, for instance the Natural Resources Defense Council believes that this figure is accurate to within a few tens [5], although the World Almanac suggests a potentially much higher value of 200-300.

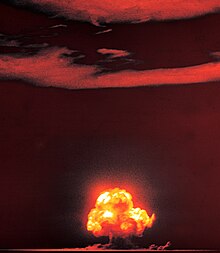

Weapons tests

Different sources give the number of test explosions that the UK has conducted as either 44[6][7] or 45[8][9]. The 23 or 24 tests from December 1962 onwards were in conjunction with the United States at their Nevada test site[10] with the final test being the Julin Bristol shot which took place on 26 November 1991.[11] The British government signed the Partial Test Ban Treaty on 5 August 1963[12] along with the United States and the Soviet Union which effectively restricted it to underground nuclear tests by outlawing testing in the atmosphere, underwater or in space. It signed the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty on 24 September 1996[13] and ratified it on 6 April 1998,[14] having passed the necessary legislation on 18 March 1998 as the Nuclear Explosions (Prohibition and Inspections) Act 1998.

Nuclear defence

Warning systems

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

The UK has relied on the Ballistic Missile Early Warning System (BMEWS) and, in later years, Defense Support Program (DSP) satellites for warning of a nuclear attack. Both of these systems are owned and controlled by the United States. One of the four component radars for the BMEWS is based at RAF Fylingdales in North Yorkshire.

In 2003 the British government stated that it will consent to a request from the US to upgrade the radar at Fylingdales for use in the US National Missile Defense system[15].

Nevertheless, missile defence is not currently a significant political issue within the UK. The ballistic missile threat is perceived to be less severe, and consequently less of a priority, than other threats to its security.[16]

Attack scenarios

During the cold war a significant effort by government and academia was made to assess the affects of a nuclear attack on Britain. A major government exercise, Square Leg, was held in September 1980 and involved around 130 warheads with a total yield of 200 megatons. This is probably the largest attack that the aparatus of the nation state could survive in some limited form. Observers have suggested that an actual exchange would be much larger with one academic describing a 200 megaton attack as an "extremely low figure and one which we find very difficult to take seriously".[17] In the early 1980s it was thought an attack causing almost complete loss of life could be achieved with the use of less than 15% of the total nuclear yield available to the Soviets.[17]

Civil defence

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

During the cold war, various governments developed civil defence programmes aimed to prepare civilian and local government infrastructure for a nuclear strike on Britain. The most famous such programme was probably the series of booklets and public information films entitled Protect and Survive.

Modern Perspectives

In 2005, the newly-elected Polish government under Kazimierz Marcinkiewicz released a hitherto-classified Warsaw Pact plan for a 1979 seven-day war with NATO forces, which used both non-nuclear and nuclear strikes to allow an advance to the River Rhine. This plan was known as Seven Days to the River Rhine, as it featured a stop line located in the Rhineland.

The associated maps show nuclear strikes in many NATO states, but France and the United Kingdom are entirely untouched by nuclear attack. It is possible that this "hands off" approach to the two nations was conducted because of the "counter value" strategy of nuclear deterrent practiced by the French and British forces.

"Counter Value" is the exchange of targets of similar human cost, rather than "Counter Force", which comprises the destruction of the opponent's striking weaponry. This means, for example, that Britain might respond to an attack on Manchester by striking Minsk, or Liverpool with Leningrad.

As even a tactical nuclear device would cause immense destruction on a compact nation such as France or Britain, and as most military bases of value are near important cities, it is likely that a counter-value strike would follow any nuclear detonation. The Soviet leadership would likely have kept this under consideration when constructing their plans.

This may be evidence that that the British nuclear deterrent rendered the United Kingdom less, rather than more, vulnerable to a potential nuclear strike by Soviet forces. There are many high-value targets in Britain (like RAF Mildenhall or RAF Lakenheath) that would then have to be struck in a conventional manner, though a nuclear strike would be far more effective (and as the plans show, preferable to the Soviet leadership in most of Western Europe).

Weapons programmes

See also History of nuclear weapons

Tube Alloys and Manhattan Project

British nuclear weapons had their genesis in the Second World War when the United Kingdom worked on development of an atomic bomb, initially on their own under the cover name of Tube Alloys but later as a partner in the American Manhattan Project. The Manhattan Project resulted in the two nuclear weapons dropped on Japan which led to that country's unconditional surrender.

Post-war development programme

The United Kingdom started independently developing nuclear weapons again shortly after the war. Labour Prime Minister Clement Attlee set up a cabinet sub-committee, GEN.75 (and known informally as the "Atomic Bomb Committee"), to examine the feasibility as early as 29 August 1945. The atomic bomb's potential to give the nation added leverage in foreign affairs helped to prompt the building of a British bomb:

In October 1946, Atlee called a small cabinet sub-committee meeting to discuss building a gaseous diffusion plant to enrich uranium. The meeting was about to decide against it on grounds of cost, when [Ernest] Bevin arrived late and said "We've get to have this thing. I don't mind it for myself, but I don't want any other Foreign Secretary of this country to be talked at or to by the Secretary of State of the US as I have just been... We've got to have this thing over here, whatever it costs." [18]

A civilian nuclear program started in 1946 under Marshal of the Royal Air Force Viscount Portal of Hungerford. It was based at two former airfields, Harwell (then in Berkshire now in Oxfordshire) and Risley in Cheshire were taken over as sites for research and manfuacture respectively. The first British nuclear pile, GLEEP, went critical at Harwell on 15 August 1947.

William Penney, a physicist specialising in hydrodynamics was asked in October 1946 to prepare a report on the viability of building a British weapon. He had joined the Manhattan project in 1944, and had been in an observation plane that accompanied the Nagasaki bomber, and had also done damage assessment on the ground following Japan's surrender. He had subsequently participated in the American Operation Crossroads test at Bikini Atoll. As a result of his report, the decision to proceed was formally made on 8 January 1947 at a meeting of the GEN.163 committee of six cabinet members, including Prime Minister Clement Attlee with Penney appointed to take charge of the programme.

The project was hidden under the name Basic High Explosive Research or BHER (later just HER) and was based initially at Woolwich Arsenal but in 1950 moved to a new site at AWRE Aldermaston in Berkshire. A particular problem was the American McMahon Act of 1946 restricting access to nuclear technology. Although British scientists knew the areas of the Manhattan Project in which they had worked well, they only had the sketchiest details of those parts which they were not directly involved in. With the start of the Cold War there had been some warming of nuclear relations between the British and American governments, which led to hopes of American cooperation. However these were quickly dashed by the arrest in early 1950 of Klaus Fuchs, a Soviet spy working at Harwell. Plutonium production reactors were based at Sellafield in Cumberland (now in Cumbria) and construction began in September 1947, leading to the first plutonium metal ready in March 1952.

First test and early systems

The first British weapon test, Operation Hurricane, was executed on HMS Plym anchored in the Monte Bello Islands on 2 October 1952. This led to the first deployed weapon, the Blue Danube free-fall bomb, in November 1953. It was very similar to the American Mark 4 weapon in having a 60 inch diameter, 32 lens implosion system with a levitated core suspended within a natural uranium tamper, and equipped the V Bomber force which had been developed to carry it.

A nuclear mine dubbed Blue Peacock and based on Blue Danube was developed from 1954 with the goal of deployment in the Rhine area of Germany. The system would have been set to an eight-day timer in the case of invasion of Western Europe by the Soviets but was cancelled in February 1958. It was judged that the risks posed by the nuclear fallout and the political aspects of preparing for destruction and contamination of allied territory were simply too high to justify.

A gaseous diffusion plant was built at Capenhurst, near Chester and started production in 1953 producing low enriched uranium (LEU). By 1957 it was capable of annually producing 125 kg of highly enriched uranium (HEU). The capacity was further increased and by 1959 it may have been producing as much as 1600 kg per year [1]. At the end of 1961, having produced between 3.8 and 4.9 tonnes of HEU it was switched over to LEU production for civil use. Additional plutonium production was provided by eight electricity generating Magnox reactors at Calder Hall and Chapelcross which started operating in 1956 and 1959 respectively.

Thermonuclear weaponry

The availability of highly enriched uranium allowed the British to develop a thermonuclear bomb, making use of the more powerful nuclear fusion reaction rather than nuclear fission. The first prototype was detonated on 15 May 1957 in Operation Grapple but only a few were eventually deployed, the first of which was Yellow Sun. Instead, having demonstrated their thermonuclear capability, and with a general thawing again of nuclear relations between the two countries, the 1958 US-UK Mutual Defence Agreement was signed, and the British were given access to the design of the smaller U.S. Mk 28 warhead and were able to manufacture copies. Under this agreement 5.4 tonnes of UK produced plutonium was sent to the U.S. in return for 6.7kg of tritium and 7.5 tonnes of HEU over the period 1960-1979, replacing Capenhurst production.

Blue Danube remained in service until 1963, when it was replaced by the Blue Steel, an air-launched cruise missile which remained in service until 1969. It was to have been replaced by Skybolt air-launched ballistic missiles purchased from the United States, and the British consequently cancelled their Blue Steel extended range upgrade and troubled Blue Streak ballistic missile projects. To British consternation, the American government cancelled Skybolt at the end of 1962.

Polaris

After the cancellation of Skybolt, the British purchased Polaris missiles for use in British-built ballistic missile submarines. The agreement between President Kennedy and Harold Macmillan, the Polaris Sales Agreement, was announced on December 21 1962 and HMS Resolution sailed on her first Polaris-armed patrol on 14 June 1968.[19] In the 1970s the UK developed a secret Polaris upgrade called Chevaline, to compensate for the Soviet ABM system. Once it became public in 1980, Chevaline generated huge controversy as it had been kept secret whilst costs rocketed. By the time it entered service in 1982 it had cost over £1bn. The final Polaris patrol took place in 1996, two years after Trident came into service.

As well as the establishment at Aldermaston, the UK nuclear weapons programme also has a factory at Burghfield nearby which assembled the weapons and is responsible for their maintenance, and had another in Cardiff which built non-fissile components and a 2000 acre (8 km²) test range at Foulness. Since 1993 the sites have been managed by private consortia. The Foulness and Cardiff facilities closed in October 1996 and February 1997 respectively.

Trident

The UK currently has four Vanguard class submarines armed with nuclear-tipped Trident missiles. The principle of operation is based on maintaining deterrent effect by always having at least one submarine at sea, and was designed for the Cold War period. One submarine is normally undergoing maintenance and the remaining two in port or on training exercises. It has been suggested that British ballistic missile submarine patrols are coordinated with those of the French.[20]

Each submarine carries 16 Trident II D-5 missiles, which can each carry up to twelve warheads. However, the British government announced in 1998 that each submarine would carry only 48 warheads (halving the limit specified by the previous government), which is an average of three per missile. However one or two missiles per submarine are probably armed with fewer warheads for "sub-strategic" use causing others to be armed with more.

The British-designed warheads are thought to be selectable between 0.3 kt, 5-10 kt and 100 kt; the yields obtained using either the unboosted primary, the boosted primary, or the entire "physics package". Although it owns the warheads, the United Kingdom does not actually own the missiles; instead it leased 58 missiles from the United States government and these are exchanged when requiring maintenance with missiles from the United States Navy's own pool.

Until August 1998, the UK also retained the WE.177 nuclear weapon manufactured in the 1960s, in air-dropped free-fall bomb and depth charge versions. This left the four Vanguard class submarines, which replaced the Polaris ones in the early 1990s, as the United Kingdom's only nuclear weapons platform. It has been estimated by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists that the United Kingdom has built around 1,200 warheads since the first Hurricane device of 1952. In terms of number of warheads, the British arsenal was at its maximum size of about 350 in the 1970s.

Replacement for Trident

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

A decision on the replacement of Trident is expected in the next few years. Former Defence Secretary John Reid has been quoted as saying "I defy anyone here to say we will not need a nuclear weapon in 20 to 50 years time".[21] "We have always maintained that as long as some other nuclear state which is a potential threat has nuclear weapons we will retain ours. That is the assumption from which we start but it has to be tested in discussions with others and it will be".[22]

Timeline

The timeline below shows the develop of warheads, nuclear delivery systems and nuclear infrastructure in the UK between 1940 and 2006. Delivery systems are charted to indicate when they were in active service. This does not include development time or decommissioning. Similarly, power plants are charted from when they became active, rather than the date of commissioning or construction. At the end of 1961, the Capenhurst reactor was switched back to low enriched uranium production for civil use. The Magnox electricity producing power stations could produce Plutonium for use in the UK military nuclear programme. Seven other Magnox reactors came onlline between 1964 and 1971 (see List of Magnox reactors in the UK), although these weren't necessarily used to generate material for warheads.

ROF Cardiff was used as part of the nuclear programme from 1961 until its closure in 1997. The Burghfield site was built in 1941 and used for the nuclear programme from the early 1950s to this day. It is now called AWE Burghfield rather than ROF Burghfield.

Deployment of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

Until 1992 UK forces also deployed U.S. tactical nuclear weapons as part of a U.S.-UK dual-key NATO nuclear sharing role [2] [3]. The weapons deployed included nuclear artillery, nuclear demolition mines and Lance missiles in Germany; theatre nuclear weapons on RAF aircraft; and nuclear depth bombs on RAF maritime patrol aircraft. The Lance missiles were purchased in 1975 [4], to replace Honest John missiles which had been bought in 1960 [5].

Research and development facilities

Atomic Weapons Establishment, Aldermaston

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

The Atomic Weapons Establishment (AWE), Aldermaston (formerly the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment, Aldermaston) is situated just 7 miles north of Basingstoke and approximately 14 miles south-west of Reading, Berkshire, near a village called Aldermaston, bordering with Tadley. It was built in 1949 on the site of a former World War II Royal Air Force base and converted to nuclear weapons production in the 1950s. This is where the final assembly of nuclear warheads and bombs takes place.

Royal Ordnance Factories, Cardiff and Burghfield

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

Other atomic weapons sites could be found in Cardiff and Burghfield near Reading, Berkshire. These were the only two Royal Ordnance Factories (ROF) not to be privatised in the 1980s.

ROF Cardiff, which closed in 1997, was involved in nuclear weapons programmes since 1961. The site was used for the task of recycling old nuclear weapons and precisely shaping and assembling depleted uranium 235 (U235) and beryllium, in metal form, into the 'triggers' and 'reflectors' used in modern nuclear weapons.[23]

Politics, decision making and nuclear posture

Nuclear posture

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

UK nuclear posture during the cold war was informed by interdependence with the United States while maintaining an independent targeting policy. The 'Moscow criterion' referred to the ability of the UK to strike back at Soviet cities in the event of an attack. The Chevaline project was undertaken almost as soon as the Polaris system was deployed in order to preserve this capability in the face of anti-ballistic missile batteries around Moscow.[24]

The UK has relaxed its nuclear posture since the collapse of the Soviet Union. The UK has reduced the total warhead stockpile, number of warheads on each missile and number of missiles deployed on each submarine.[citation needed]

The special relationship

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

The 1958 'Agreement For Cooperation on the Uses of Atomic Energy for Mutual Defence Purposes' also known as the 'Mutual Defence Agreement' was renewed in 1994 and again in 2005.[25]

Parliament and civil society

The UK's possession of nuclear weapons has appeared essential for successive governments in order to maintain the UK's diplomatic influence abroad, and in particular to protect its right to a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council (the five permanent members being the original five nuclear powers). In the near future, decisions about the replacement of Trident will need to be made (because of the long lead time before a replacement could enter service). Although the Labour Party in the 1980s was in favour of nuclear disarmament, it seems that the current Labour government will decide to replace Trident - although there may be some legal issues relating to the non-proliferation treaty.

The current Trident system cost £12.6bn (at 1996 prices) and costs £280m a year to maintain. Options for replacing Trident range from £5bn for the missiles alone to £20-30bn for missiles, submarines and research facilities. At minimum, for the system to continue safely after around 2020, the missiles will need to be replaced.[6]

See also

Footnotes

- ^ Secret plans for Trident replacement, Tim Ripley, The Scotsman, 9 June 2004

- ^ Point 64, Strategic Defence Review, Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Defence, George Robertson, July 1998

- ^ SIPRI project on nuclear technology and arms

- ^ House of Commons Written Answers, Hansard, 14 Jul 1998 : Column: 171

- ^ Table of Global Nuclear Weapons Stockpiles, 1945-2002, National Resources Defense Coundil, 25 November 2002

- ^ Press Release, Verification Technology Information Centre, 17 August 1995

- ^ Weapons around the world, Jon Wolfsthal, physicsweb, August 2005

- ^ Nuclear Weapons Milestons (Part 1-B), compiled by Wm. Robert Johnston, 3 June 2005

- ^ History of Nuclear Weapons Testing, Greenpeace, April 1996

- ^ Database of nuclear tests, United Kingdom, compiled by Wm. Robert Johnston, last modified 19 June 2005

- ^ History of the British Nuclear Arsenal, Last changed 30 April 2002

- ^ Inventory of International Nonproliferation Organizations and Regimes, Center for Nonproliferation Studies.

- ^ House of Commons Debate, Nuclear Explosions (Prohibition and Inspections) Bill, Hansard, 6 Nov 1997 : Column 455

- ^ Status of CTBT Ratification, British American Security Information Council, last updated on 14 June 2001

- ^ Statement by the Secretary of State for Defence, Hansard 15 Jan 2003 : Column 697

- ^ Royal United Services Institute - Ballistic Missile Defence and the UK April 2005

- ^ a b Possible Nuclear Attack Scenarios on Britain, Paul Rogers, Proceedings of Conference on Nuclear Deterrence: Implications and Policy Options for the 1980s, September 1981

- ^ Sir M. Perrin, who was present, The Listener, 7 October 1982. Also quoted in How Nuclear Weapons Decisions are Made, p.137, 1986, Oxford Research Group.

- ^ Amazon.co.uk review, The Impact of Polaris: The Origins of Britain's Seaborne Nuclear Deterrent, J.E. Moore.

- ^ British nuclear forces, 2001, Robert S. Norris, William M. Arkin, Hans M. Kristensen, and Joshua Handler, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, November/December 2001 pp. 78-79 (vol. 57, no. 06)

- ^ Reid hints at Trident replacement, Matthew Tempest and agencies, The Guardian, 1 November 2005

- ^ General Evidence Session with the Secretary of State for Defence, House of Commons Defence Select Committee, Oral Evidence, 1 November 2005

- ^ How Nuclear Weapons Decisions are Made, Scilla McClean (ed), Oxford Research Group, 1984, [ISBN 0333405838], p. 120

- ^ British Nuclear Doctrine: The 'Moscow Criterion' and the Polaris Improvement Programme, John Baylis, Contemporary British History, Vol. 19, No. 1, Spring 2005, pp.53-65

- ^ US-UK nuclear weapons collaboration under the Mutual Defence Agreement, Nigel Chamberlain, Nicola Butler and Dave Andrews, British American Security Council, June 2004

Further reading

- Paul Rogers, "Possible Nuclear Attack Scenarios on Britain", Proceedings of the Conference on Nuclear Deterrence, Implications and Policy Options for the 1980s, International Standing Conference on Conflict and Peace Studies, London, 1982.

External links

- British Nuclear Policy, BASIC

- Table of UK Nuclear Weapons models

- Trident: the done deal, Robert Fox, The New Statesman, 13 June 2005

- Trident: we've been conned again, Dan Plesch, The New Statesman, 27 March 2006

- Table of British nuclear weapons tests

- Text of the Nuclear Explosions (Prohibition and Inspections) Act 1998

- Nuclear Notebook: British nuclear forces, 2001, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Nov/Dec 2001.

- The United Kingdom's Defence Nuclear Programme, UK Ministry of Defence, 4 September 2001

- British Nuclear Forces, 2005, by Robert S. Norris and Hans M. Kristensen. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, November/December 2005.

- Britain's secret nuclear blueprint The Sunday Times, March 12, 2006

- Revealed: UK develops secret nuclear warhead by Michael Smith, The Sunday Times, March 12, 2006