Helena Blavatsky

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

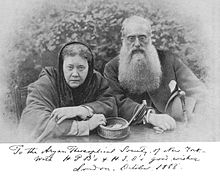

Helena Blavatsky | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Helena von Hahn 12 August 1831 |

| Died | 8 May 1891 (aged 59) |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Parent | Peter Alekseevich Hahn |

| Part of a series on |

| Theosophy |

|---|

|

Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (Russian: Еле́на Петро́вна Блава́тская, Ukrainian: Олена Петрівна Блаватська), born as Helena von Hahn (Russian: Елена Петровна Ган, Ukrainian: Олена Петрівна Ган; 12 August [O.S. 31 July] 1831 – 8 May 1891), was a Ukrainian occultist.[1]

In 1875, Blavatsky, Henry Steel Olcott, and William Quan Judge established a research and publishing institute called the Theosophical Society. Blavatsky defined Theosophy as "the archaic Wisdom-Religion, the esoteric doctrine once known in every ancient country having claims to civilization."[2] One of the main purposes of the Theosophical Society was "to form a nucleus of the Universal Brotherhood of Humanity, without distinction of race, creed, sex, caste or color".[3] Blavatsky saw herself as a missionary of this ancient knowledge.

Her extensive research into the spiritual traditions of the world led to the publication of what is now considered her magnum opus, The Secret Doctrine, which organizes the essence of these teachings into a comprehensive synthesis. Blavatsky's other works include Isis Unveiled, The Key to Theosophy and The Voice of the Silence. Well-known and controversial during her life, Blavatsky was no stranger to criticism. Some authors have questioned the authenticity of her writings and the validity of her claims.[4][a] while others have praised them.[6][7] Blavatsky is a leading name in the New Age Movement.

The Theosophical Society had a major influence on Buddhist modernism[8] and Hindu reform movements, and the spread of those modernised versions in the west.[8] Along with Olcott and Anagarika Dharmapala, Blavatsky was instrumental in the Western transmission and revival of Theravada Buddhism.[9]

Biography

Childhood and youth

She was born on 31 July (12 August new style), 1831, at Yekaterinoslav (from 1926 Dnipropetrovsk). Her parents were Colonel Peter von Hahn (Russian: Пётр Алексеевич Ган, 1798–1873) of the ancient von Hahn family of German nobility (German: Uradel) from Basedow (Mecklenburg) and her mother Helena Andreevna von Hahn (Fadeyeva).

Her father's profession required the family to move often; a year after Blavatsky's birth, the family moved to Romankovo (now part of Dneprodzerzhinsk), and in 1835 they moved to Odessa, where Blavatsky's sister, Zhelihovsky, was born. Later the family lived in Tula and Kursk. In the spring of 1836 they arrived in St. Petersburg where they lived until May 1837. From St. Petersburg, Blavatsky, along with her sister, mother, and grandfather Andrei Mikhailovich Fadeyev moved to Astrakhan. There, Andrei Mikhailovich was an officer in charge of Kalmyks and local German colonists.[10] In 1838, Blavatsky's mother moved with her daughters to Poltava, where she began to take dance lessons and her mother taught her to play the piano.

In spring 1839, the family moved to Odessa. There Helena Andreevna found a governess for her children, who taught them English.[11] In November, Blavatsky's grandfather Andrei Mikhailovich was assigned governor of Saratov by Emperor Nikolai I. After this, Helena Andreevna and her children moved to live with him. In June 1840, at Saratov, Helena Andreevna's son Leonid was born. Blavatsky was then nine years old. Nadejda Fadeyeva, Blavatsky's aunt, wrote to Alfred Sinnett of her memory of her niece:

Richard Davenport-Hines described her as "a petted, wayward, invalid child" who was a "beguiling story-teller", in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.[12]

In childhood, all [Helena's] likings and interests were concentrated on the people from lower estates. She preferred to play with the children of domestics but not with equals. <…> She always needs attention to prevent her escape from home and meetings with street ragamuffins. And at a mature age she irrepressibly reached out to those whose status was lower than her own, and displayed a marked indifference to the "nobles", to which she belongs by birth.[13]

At ten years old, she began to study German. Her progress was so appreciable that, according to Zhelihovsky, her father "complimented her, and in jest called her a worthy heiress of her glorious ancestors, German knights Hahn-Hahn von der Rother Hahn, who knew no other language besides German."

In 1841, the family returned to Ukraine. On 6 July 1842, Helena Andreevna Hahn, Helena's mother and at that time a well-known writer, died at the age of 28 of galloping consumption.

According to Zhelihovsky, Helena's mother, at the time, was worried about the destiny of her elder daughter, "gifted from childhood with outstanding features".[14] Before her death, her mother said: "Well! Perhaps it is for the better that I am dying: at least, I will not suffer from seeing Helena's hard lot! I am quite sure that her destiny will be not womanly, that she will suffer much".[15]

After her mother's death, Helena's grandfather Andrei Mikhailovich and grandmother Helena Pavlovna took the children to Saratov, where they had quite a different life. Fadeyev's house was visited by Saratov's intellectuals. A well-known historian, Kostomarov, and writer, Mary Zhukova, were among them.[16] Blavatsky's grandmother and three teachers were occupied with the children's upbringing and education, so she received a solid home education.[17][18]

Blavatsky's favorite place in the house was her grandmother's library, which Helena Pavlovna inherited from her father.[18] In this voluminous library, Blavatsky paid special attention to the books on medieval occultism.[b]

In 1847, the family had moved from Saratov to Tiflis (present-day Tbilisi, Georgia), where Andrei Mikhailovich was invited to work at the Council of Senior Governance in the Transcaucasia region.[20] Pisareva wrote that:

They who knew her … in youth remember with delight her inexhaustibly merry, cheerful, sparkling with wit. She liked jokes, teasing and to cause a commotion.[21]

Pisareva wrote that Nadejda Fadeyeva remembered that:

As a child, as a young woman, as a woman, she always was so higher than her surroundings that she never was could not appreciate its true value. She was trained as a girl from good family … extraordinary wealth in the form of her intellectual faculties, fineness and quickness of thought, amazing understanding and learning of most difficult disciplines, unusually developed mind together with chivalrous, direct, energetic and open character—this is what raised her so high over the level of conventional society and could not help attracting the common attention and therefore the envy and hostility from these who with their nonentity can not stand of luster and gifts of this wonderful nature.[21]

In youth, Blavatsky had a high life, often was in society, danced at the balls and visited the parties. But when she reached 16, she experienced a sudden inner change, and she began to study the books from her great-grandfather's library more deeply.[22]

Pisareva cited the reminiscences of Mary Grigor'evna Yermolova, wife of the Tiflis governor: "Simultaneously with Fadeev's family, in Tiflis lived a relation of the Caucasian Governor-general, prince Golitsin. He often visited Fadeyevs and was greatly interested by an original young woman". Due to Golitsin (Yermolova did not cite his name) who, as it was rumored, was "either mason or magician or soothsayer" Blavatsky tried "to come into contact with a mysterious sage of the East where prince Golitsin was going to".[21] This version was further supported by many biographers of Blavatsky.;[23][24][25] [26] According to A. M. Fadeyev and V. P. Jelihovsky, at the end of 1847, an old friend of Andrei Mikhailovich prince Vladimir Sergeevich Golitsin (1794–1861), Major General, Head of the Caucasian line centre and further privy councilor,[27] arrived to Tiflis and lived there a few months. He almost daily visited Fadeyevs, and often with his young sons Sergei (1823–1873) and Alexander (1825–1864).[28] Therefore, some researchers of Blavatsky consider the information from M. Yermolova about prince Golitsin improbable because the young Golitsin's sons did not correspond to Yermolova's description because of age, and aged prince Golitsin could not be "strongly interested for an original young woman" because of moral reasons. In addition, according to his biographers, Golitsin never was going to the East.[27] and [29]

Striving for full independence during the winter of 1848/1849 at Tiflis, she entered into a sham marriage with General Nikifor Vasilyevich Blavatsky, the much older vice-governor of Erevan, on 7 July 1848.[12] Soon after their wedding, she escaped from her husband and returned to her relatives.[30] Russian law at the time did not allow divorce.[31] Further, she was going to Odessa and sailed away from Poti to Kerch in the English sailboat "Commodore". Then she moved to Constantinople. There she met a Russian countess Kiseleva, and together they traveled over Egypt, Greece and Eastern Europe.[32] Blavatsky's assertions about her courageous adventures "seem partly authentic" to Davenport-Hines.[12]

Travels

The next period of Blavatsky's life is difficult for her biographers, as she did not keep diaries and there was nobody with her to tell about these events. In general, a picture of a route and course of the travels is based mainly on Blavatsky's memoirs, which sometimes contain chronological contradictions. Nadejda Fadeyeva reported that of all her relatives only her father knew where she was, and from time to time he sent money to her. It is known that Blavatsky met an art student named Albert Rawson (1828-1902) in Cairo. After Blavatsky's death, Rawson, who by that time was a doctor of theology and of law at Oxford, described their meeting at Cairo. According to her memory, Blavatsky told him about her future participation in the work which some day would serve to liberate the human mind. Rawson wrote:

Her relation to her mission was highly impersonal because she often repeated: "This work is not mine, but he who sends me."

According to Blavatsky's reminiscences, after leaving the Middle East she began to travel Europe with her father. It is known that at this time she learned to play piano with Ignaz Moscheles, the well-known composer and virtuoso pianist. Later she gave several concerts in England and other countries.

In 1851, on her birthday (12 August), Blavatsky met her Teacher for the first time in Hyde Park in London. Previously, she had seen this Teacher in her dreams. Countess Konstanz Wachtmeister, widow of the Swedish ambassador at London, remembered the details of this conversation in which Blavatsky's Teacher said that he "needs her participation in the work he is going to undertake" and "she will live three years in Tibet to prepare for this important mission." After leaving England, Blavatsky went to Canada, then to Mexico, Central and South America. In 1852 she arrived in India, where she remembered, "I lived there about two years and received money monthly from [an] unknown person. I honestly followed the pointed route. I received letters from this Hindu but [have] not once seen him during these two years".

Before leaving India, Blavatsky tried to enter Tibet through Nepal but a British representative would not permit it.

From India, Blavatsky went back to London, where, according to Zhelihovsky, she acquired "fame by her musical talent. She was a member of the philharmonic society". Here, according to Blavatsky, she met her Teacher again. After this meeting she went to New York, where she again met Rawson. Then, according to Sinnett, she traveled to Chicago, and further, together with settler caravans, to the West through the Rocky Mountains. After this, she stayed some time in San Francisco. In 1855 (or 1856), she sailed across the Pacific Ocean to the Far East, via Japan and Singapore, to arrive in Calcutta.

In 1856, Blavatsky's memories about living in India were published in the book From the Caves and Jungles of Hindustan. The book was composed of essays written from 1879 to 1886 under the pen name "Radda-Bay". The essays were first published in Moskovskie vedomosti, a newspaper edited by Mikhail Katkov, and attracted great interest among the readership. Katkov republished them as an attachment to The Russian Messenger along with new letters written specially for this journal. In 1892, the book was partially translated into English; in 1975 it was fully translated into English.

In From the Caves and Jungles of Hindustan, Blavatsky described her travels with her Teacher, whom she named Takhur Gulab-Singh. Though the book was considered a novel, she asserted that "the facts and persons that I cited are true. I simply collected to time interval in three-four months the events and cases occurring during several years just like the part of the phenomena that the Teacher has shown."

In 1857, Blavatsky repeatedly tried to pass to Tibet from India via Kashmir but shortly before the Mutiny she received instructions from her Teacher and sailed on a Dutch ship from Madras to Java. Later she returned to Europe.

Blavatsky spent several months in France and Germany, and then she moved to Pskov to be with her relatives. She arrived on Christmas night of 1858. According to Jelihovsky, Blavatsky returned from the travels as "a human gifted by exceptional features and forces amazing [to] all the people around her".

In May 1859 Blavatsky moved with her family to the village Rugodevo in the Novorzhev district, where she stayed for almost a year. This period ended with Blavatsky falling ill. In the spring of 1860, after she recovered, she, together with her sister, moved to Caucasus to visit her grandparents.

Jelihovsky reported that on the way to Caucasus, at Zadonsk, Blavatsky met the former exarch, Georgia Isidor. He was the Metropolitan of Kiev and then Novgorod, St-Petersburg and Finland. Isidor gave his blessing to Blavatsky. (Details see below). From Russia, Blavatsky began to travel again. Although her route is not known for certain, she probably visited Persia, Syria, Lebanon, Jerusalem and went multiple times to Egypt, Greece and Italy.

Frederic Boase wrote that she "kept a gambling hell in Tiflis about 1863."[31] From 1863, she traveled in Europe and "averred" that she was wounded, in 1867, at the Battle of Mentana.[12]

On the beginning of 1868, when Blavatsky recovered from her wounds, she moved to Florence. Then she traveled to Northern Italy and the Balkans and further to Constantinople, India and Tibet.

Later, when she answered to the question why she traveled to Tibet, Blavatsky wrote:

Really, it is quite useless to go to Tibet or India to recover some knowledge or power that are hidden in any human soul; but acquisition of higher knowledge and power requires not only many years of intensive studying under the guidance of higher mind together with a resolution that cannot be shaken by any danger, and as much as years of relative solitude, in communication with disciples only which pursue the same aim, and in such a place where both the nature and the neophyte preserve a perfect and unbroken rest if not the silence! There the air is not poisoned by miasmas around a hundreds miles, and there the atmosphere and human magnetism are quite clear and there the animal's blood is never shed.

According to biographers, Blavatsky's path led to Tashilhunpo Monastery (near Shigatse). A book The Voice of the Silence, published for the request of Thubten Choekyi Nyima, 9th Panchen Lama, in 1927 by Chinese society for Buddhism study at Peking, reports that Blavatsky during several years studied in Tashilhunpo Monastery and knew Tenpai Wangchuk, 8th Panchen Lama, well. Blavatsky also confirmed living at Tashilhunpo Monastery and Shigatse. In a letter, she depicted for her correspondent a solitary temple of Tashi Lama near Shigatse.

Sylvia Cranston asserts that, according to Blavatsky, it was not known she was at Lhasa in that time, but Jelihovsky affirmed the follows: "It is reliably that she (Blavatsky) sometimes was at Lhasa, capital of Tibet, and also at Shigatse, main Tibetan religious centre … and at Karakoram mountains in Kunlun Shan. Her living stories about this proved that for me many times".

According to the biographers, Blavatsky's last period of living in Tibet was in the home of her Teacher Koot Hoomi (K.H.). He also helped Blavatsky to get to several lamaseries where no European had been before her. In the letter from 2 October 1991 (?) she wrote to M. Hillis-Billing that the house of Teacher K.H. "is in the region of Karakoram mountains beyond Ladakh which is at minor Tibet and related now to Kashmir. This is a large wooden building in China style looking like to pagoda located between lake and a nice river".

Researchers believe that just at this time (while living in Tibet) Blavatsky began to study the texts which later will come to the book The Voice of the Silence.

One of the eminent explorers of Tibet and its philosophy Walter Evans-Wentz cited The Secret Doctrine in his 1927 translation of The Tibetan Book of the Dead as a comparison to "the esoteric meaning of forty-nine days of the bardo."[33] Evans-Wentz wrote that Lama Kazi Dawa Samdup believed that "despite the adverse criticisms directed toward" Blavatsky's works, "there is adequate internal evidence in them of their author's intimate acquaintance with the higher lāmastic teaching, into which she claimed to have been initiated."[34] Gunapala Piyasena Malalasekera, founder of the World Buddhist brotherhood, wrote about Blavatsky in Encyclopedia of Buddhism: "Her acquaintance with Tibetan Buddhism and also with esoteric Buddhism practices is indubitable". Thus, Japanese philosopher and Buddhologist D. T. Suzuki supposes that "undoubtedly Ms. Blavatsky somehow or other was initiated into deeper propositions of the Mahayana teaching".

After almost three years living at Tibet, Blavatsky began to travel through Middle East. Then she visited Cyprus and Greece.

In 1871, during the travel from Piraeus to Egypt on the ship "Evnomia" the powder magazine blew up and the ship was destroyed. Thirty passengers died. Blavatsky escaped but lost her luggage and money.

In 1871, Blavatsky arrived to Cairo where she has founded, with Emma and Alexis Coulomb, the Société Spirite, a Spiritualistic society aimed on studying of mental phenomena. However, soon the society turned out in centre of financial scandal and was disbanded[c]

In July 1872, after leaving of Cairo, Blavatsky came to Odessa through Syria, Palestine and Constantinople where she lived for nine months.

Witte, her cousin, remembered that Blavatsky "when settled at Odessa, <…> firstly opened a shop and factory for ink and then a flower shop (for artificial flowers). At this time she often visited my mother. … When I make the acquaintance of her, I was surprised by her colossal talent to grasp any thing very quickly. … Many times before my very eyes she wrote the longest letters to her friends and relatives. … In the main, she was very not unkindly woman. She has so huge blue eyes that I never see in my life".

On April 1873, Blavatsky moved from Odessa to Bucharest to visit her friend. Then she came to Paris where she lived with her first cousin Nikolai Hahn. In the end of July, she purchased a ticket to New York. Olcott and Countess K. Vahtmeister reported that when Blavatsky saw a poor woman with two children who could not pay the fare, she changed her first-class ticket for four third-class tickets and traveled the Pacific Ocean for two weeks in third-class.

Main creative period

In 1873, Blavatsky moved to Paris and then to the USA where she met Olcott.[d] Both "were closely concerned with Spiritualist investigations" and met at the Eddy Brothers' home in Vermont. "They were also concerned in the claimed phenomena of the mediums Mr. and Mrs. Nelson Holmes of Philadelphia, who were accused of cheating. The Holmes partnership involved the alleged manifestation of the spirits 'Katie King' and 'John King', associated with the British medium Florence Cook. Blavatsky eventually disowned the Holmes phenomena, but endorsed the reality of the spirit 'John King'."[36] In "1875 Blavatsky and Olcott formed the Miracle Club, which offered an alternative to prevailing scientific materialism, but the organization languished. Soon Olcott began to receive messages through Blavatsky from a mysterious 'Brother-hood of Luxor',[e] prototypes of the famous Mahatma letters of later years."[36] On April 3, 1875, in New York, Blavatsky formally married Michael Betanelly, a Georgian living in America. The marriage dissolved after several months.[38] The Theosophical Society was founded by Olcott, Blavatsky, and Judge later in 1875.[36] In 1878 she became a naturalized American citizen.[39]

In February 1879, Blavatsky and Olcott left for Bombay. In 1882, they founded a headquarters of the Theosophical Society in Adyar, in the southern suburbs of Madras, which still exists today. From 1879 to 1888 Blavatsky edited the magazine The Theosophist.

They soon met Sinnett, editor of the government Allahabad's newspaper The Pioneer. Sinnett was seriously interested in the activities of the Society. Using Blavatsky's mediation, he began to correspond with Mahatmas. While Sinnett was against the publication of these letters in total volume, he selected for publication some fragments which, as he believed, reflected the Mahatmas' thoughts exactly enough. The full correspondence was published by Alfred Barker in 1923, after Sinnett's death.[40]

According to Randi, in India, she was "a cult figure for several years, until a housekeeper who had formerly worked as a magician's assistant exposed the tricks by which Blavatsky had been fooling her followers." The exposure became known as the Coulomb Affair. She "threatened to sue, but instead chose to leave India, and never went back."[35] Blavatsky left India in 1885, making her way to Germany and Belgium, where she lived for some time. She later moved to London where she was occupied with writing of the books. She then wrote The Secret Doctrine (1888), The Key to Theosophy (1889), and The Voice of the Silence (1889).

During these years, she had also made some influential friends, like Camille Flammarion, Thomas Edison and William Cookes.[41]

Death

On 8 May 1891 Blavatsky died of influenza.[42][f] Her body was cremated at Woking Crematorium.[12] The ashes were divided between three centers of the theosophical movement: London, New York and Adyar. Her followers commemorate the anniversary of her death, on the eighth of May, as White Lotus Day.

Theosophical Society

Blavatsky helped found the Theosophical Society in New York City in 1875 with the motto, "There is no Religion higher than Truth". Its other principal founding members include Olcott and Judge. After several changes and iterations its declared objectives became the following:[43]

- To form a nucleus of the Universal Brotherhood of Humanity, without distinction of race, creed, sex, caste, or color.

- To encourage the study of Comparative Religion, Philosophy, and Science.

- To investigate the unexplained laws of Nature and the powers latent in man.

The Society was organized as a non-proselytizing, non-sectarian entity.[g] Blavatsky and Olcott (the first President of the Society) moved from New York to Bombay, India in 1878. The International Headquarters of the Society was eventually established in Adyar, a suburb of Madras. Following Blavatsky's death, disagreements among prominent Theosophists caused a series of splits and several Theosophical Societies and Organizations emerged. As of 2011[update] Theosophy remains an active philosophical school with presences in more than 50 countries around the world.[h]

Spiritualism

Blavatsky wrote, in Isis Unveiled, that Spiritualism "alone offers a possible last refuge of compromise between" the "revealed religions and materialistic philosophies." While she acknowledged that fanatic believers "remained blind to its imperfections", she wrote that such a fact was "no excuse to doubt its reality" and asserted that Spiritualist fanaticism was "itself a proof of the genuineness and possibility of their phenomena."[45]

Theosophy

Template:Merge section to Blavatsky is most well known for her promulgation of a theosophical system of thought, often referred to under various names, including: The Occult Science, The Esoteric Tradition, The Wisdom of the Ages, etc., or simply as Occultism or Theosophy.

Definition and origin

Theosophy was considered by Blavatsky to be "the substratum and basis of all the world-religions and philosophies".[46] In The Key to Theosophy, she stated the following about the meaning and origin of the term:

ENQUIRER. Theosophy and its doctrines are often referred to as a new-fangled religion. Is it a religion?

THEOSOPHIST. It is not. Theosophy is Divine Knowledge or Science.

ENQUIRER. What is the real meaning of the term?

THEOSOPHIST. "Divine Wisdom," (Theosophia) or Wisdom of the gods, as (theogonia), genealogy of the gods. The word theos means a god in Greek, one of the divine beings, certainly not "God" in the sense attached in our day to the term. Therefore, it is not "Wisdom of God", as translated by some, but Divine Wisdom such as that possessed by the gods. The term is many thousand years old.

ENQUIRER. What is the origin of the name?

THEOSOPHIST. It comes to us from the Alexandrian philosophers, called lovers of truth, Philaletheians, from phil "loving," and aletheia "truth". The name Theosophy dates from the third century of our era, and began with Ammonius Saccas and his disciples, who started the Eclectic Theosophical system.[47]

According to her, all real lovers of divine wisdom and truth had, and have, a right to the name of Theosophist.[48] Blavatsky discussed the major themes of Theosophy in several major works, including The Secret Doctrine, Isis Unveiled, The Key to Theosophy, and The Voice of the Silence. She also wrote over 200 articles in various theosophical magazines and periodicals.[49] Contemporaries of Blavatsky, as well as later theosophists, contributed to the development of this school of theosophical thought, producing works that at times sought to elucidate the ideas she presented (see Gottfried de Purucker), and at times to expand upon them.[i] Since its inception, and through doctrinal assimilation or divergence, Theosophy has also given rise to or influenced the development of other mystical, philosophical, and religious movements.[50]

Scope

Broadly, Theosophy attempts to reconcile humanity's scientific, philosophical, and religious disciplines and practices into a unified worldview. As it largely employs a synthesizing approach, it makes extensive use of the vocabulary and concepts of many philosophical and religious traditions. However these, along with all other fields of knowledge, are investigated, amended, and explained within an esoteric or occult framework. In often elaborate exposition, Theosophy's all-encompassing worldview proposes explanations for the origin, workings and ultimate fate of the universe and humanity; it has therefore also been called a system of "absolutist metaphysics".[51][j]

Methodology

According to Blavatsky, Theosophy is neither revelation nor speculation.[k] It is portrayed as an attempt at gradual, faithful reintroduction of a hitherto hidden science, which is called in Theosophical literature The Occult Science. According to Blavatsky, this postulated science provides a description of Reality not only at a physical level, but also on a metaphysical one. The Occult Science is said to have been preserved (and practiced) throughout history by carefully selected and trained individuals.[l] Theosophists further assert that Theosophy's precepts and their axiomatic foundation may be verified by following certain prescribed disciplines that develop in the practitioner metaphysical means of knowledge, which transcend the limitations of the senses. It is commonly held by Theosophists that many of the basic Theosophical tenets may in the future be empirically and objectively verified by science, as it develops further.

Law of correspondences

In The Secret Doctrine, Blavatsky spoke of a basic item of cosmogony reflected in the ancient saying: "as above, so below". This item is used by many theosophists as a method of study and has been called "The Law of Correspondences". Briefly, the law of correspondences states that the microcosm is the miniature copy of the macrocosm and therefore what is found "below" can be found, often through analogy, "above". Examples include the basic structures of microcosmic organisms mirroring the structure of macrocosmic organisms (see septenary systems, below). The lifespan of a human being can be seen to follow, by analogy, the same path as the seasons of the Earth, and in theosophy it is postulated that the same general process is equally applied to the lifespan of a planet, a solar system, a galaxy and to the universe itself. Through the Law of Correspondences, a theosophist seeks to discover the first principles underlying various phenomenon by finding the shared essence or idea, and thus to move from particulars to principles.

Applications

Applied Theosophy was one of the main reasons for the foundation of the Theosophical Society in 1875; the practice of Theosophy was considered an integral part of its contemporary incarnation.[m] Theosophical discipline includes the practice of study, meditation, and service, which are traditionally seen as necessary for a holistic development. Also, the acceptance and practical application of the Society's motto and of its three objectives are part of the Theosophical life. Efforts at applying its tenets started early. Study and meditation are normally promoted in the activities of the Theosophical Society, and in 1908 an international charitable organization to promote service, the Theosophical Order of Service, was founded.

Terminology

Despite extensively using Sanskrit terminology in her works, many Theosophical concepts are expressed differently from in the original scriptures. To provide clarity on her intended meanings, Blavatsky's The Theosophical Glossary was published in 1892, one year after her death. According to its editor, George Robert Stowe Mead, Blavatsky wished to express her indebtedness to four works: the Sanskrit-Chinese Dictionary, the Hindu Classical Dictionary, Vishnu Purana, and The Royal Masonic Cyclopaedia.[57]

Basic tenets

Three fundamental propositions

Blavatsky explained the essential component ideas of her cosmogony in her magnum opus, The Secret Doctrine. She began with three fundamental propositions, of which she said:

Before the reader proceeds … it is absolutely necessary that he should be made acquainted with the few fundamental conceptions which underlie and pervade the entire system of thought to which his attention is invited. These basic ideas are few in number, and on their clear apprehension depends the understanding of all that follows…[58]

The first proposition is that there is one underlying, unconditioned, indivisible Truth, variously called "the Absolute", "the Unknown Root", "the One Reality", etc. It is causeless and timeless, and therefore unknowable and non-describable: "It is 'Be-ness' rather than Being".[n] However, transient states of matter and consciousness are manifested in IT, in an unfolding gradation from the subtlest to the densest, the final of which is physical plane.[59] According to this view, manifest existence is a "change of condition"[o] and therefore neither the result of creation nor a random event.

Everything in the universe is informed by the potentialities present in the "Unknown Root," and manifest with different degrees of Life (or energy), Consciousness, and Matter.[p]

The second proposition is "the absolute universality of that law of periodicity, of flux and reflux, ebb and flow". Accordingly, manifest existence is an eternally re-occurring event on a "boundless plane": "'the playground of numberless Universes incessantly manifesting and disappearing,'"[62] each one "standing in the relation of an effect as regards its predecessor, and being a cause as regards its successor",[63] doing so over vast but finite periods of time.[q]

Related to the above is the third proposition: "The fundamental identity of all Souls with the Universal Over-Soul... and the obligatory pilgrimage for every Soul—a spark of the former—through the Cycle of Incarnation (or 'Necessity') in accordance with Cyclic and Karmic law, during the whole term." The individual souls are seen as units of consciousness (Monads) that are intrinsic parts of a universal oversoul, just as different sparks are parts of a fire. These Monads undergo a process of evolution where consciousness unfolds and matter develops. This evolution is not random, but informed by intelligence and with a purpose. Evolution follows distinct paths in accord with certain immutable laws, aspects of which are perceivable on the physical level. One such law is the law of periodicity and cyclicity; another is the law of karma or cause and effect.[65]

Cosmic evolution

Items of cosmogony

In this recapitulation of The Secret Doctrine, Blavatsky gave a summary of the central points of her system of cosmogony.[66] These central points are as follows:

- The first item reiterates Blavatsky's position that The Secret Doctrine represents the "accumulated Wisdom of the Ages", a system of thought that "is the uninterrupted record covering thousands of generations of Seers whose respective experiences were made to test and to verify the traditions passed orally by one early race to another, of the teachings of higher and exalted beings, who watched over the childhood of Humanity."

- The second item reiterates the first fundamental proposition (see above), calling the one principle "the fundamental law in that system [of cosmogony]". Here Blavatsky says of this principle that it is "the One homogeneous divine Substance-Principle, the one radical cause. … It is called "Substance-Principle," for it becomes "substance" on the plane of the manifested Universe, an illusion, while it remains a "principle" in the beginningless and endless abstract, visible and invisible Space. It is the omnipresent Reality: impersonal, because it contains all and everything. Its impersonality is the fundamental conception of the System. It is latent in every atom in the Universe, and is the Universe itself."

- The third item reiterates the second fundamental proposition (see above), impressing once again that "The Universe is the periodical manifestation of this unknown Absolute Essence.", while also touching upon the complex Sanskrit ideas of Parabrahmam and Mulaprakriti. This item presents the idea that the One unconditioned and absolute principle is covered over by its veil, Mulaprakriti, that the spiritual essence is forever covered by the material essence.

- The fourth item is the common eastern idea of Maya (illusion). Blavatsky states that the entire universe is called illusion because everything in it is temporary, i.e. has a beginning and an end, and is therefore unreal in comparison to the eternal changelessness of the One Principle.

- The fifth item reiterates the third fundamental proposition (see above), stating that everything in the universe is conscious, in its own way and on its own plane of perception. Because of this, the Occult Philosophy states that there are no unconscious or blind laws of Nature, that all is governed by consciousness and consciousnesses.

- The sixth item gives a core idea of theosophical philosophy, that "as above, so below". This is known as the "law of correspondences", its basic premise being that everything in the universe is worked and manifested from within outwards, or from the higher to the lower, and that thus the lower, the microcosm, is the copy of the higher, the macrocosm. Just as a human being experiences every action as preceded by an internal impulse of thought, emotion or will, so too the manifested universe is preceded by impulses from divine thought, feeling and will. This item gives rise to the notion of an "almost endless series of hierarchies of sentient beings", which itself becomes a central idea of many theosophists. The law of correspondences also becomes central to the methodology of many theosophists, as they look for analogous correspondence between various aspects of reality, for instance: the correspondence between the seasons of Earth and the process of a single human life, through birth, growth, adulthood and then decline and death.

Anthropogenesis

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2012) |

"The real line of evolution differs from the Darwinian, and the two systems are irreconcilable," according to Blavatsky, "except when the latter is divorced from the dogma of 'Natural Selection'." She explained that, "by 'Man' the divine Monad is meant, and not the thinking Entity, much less his physical body." "Occultism rejects the idea that Nature developed man from the ape, or even from an ancestor common to both, but traces, on the contrary, some of the most anthropoid species to the Third Race man." In other words, "the 'ancestor' of the present anthropoid animal, the ape, is the direct production of the yet mindless Man, who desecrated his human dignity by putting himself physically on the level of an animal."[67]

Esotericism and symbolism

In The Secret Doctrine, Blavatsky quoted Gerald Massey a "suggestive analogy between the Aryan or Brahmanical and the Egyptian esotericism" She said that the "seven rays of the Chaldean Heptakis or Iao, on the Gnostic stones" represent the seven large stars of the Egyptian "Great Bear" constellation, the seven elemental powers, and the Hindu "seven Rishis".[68][69] Blavatsky saw the seven rays of the Vedic sun deity Vishnu as representing the same concept as the "astral fluid or 'Light' of the Kabalists," and said that the seven emanations of the lower seven sephiroth are the "primeval seven rays", and "will be found and recognized in every religion."[r]

Theosophy holds that the manifested universe is ordered by the number seven,[70] a common claim among Esoteric and mystical doctrines and religions. Thus, the evolutionary "pilgrimage" proceeds cyclically through seven stages, the three first steps involving an apparent involution, the fourth one being one of equilibrium, and the last three involving a progressive development.

There are seven symbols of particular importance to the Society's symbology:

- the seal of the Society

- a serpent biting its tail

- the gnostic cross (near the serpent's head)

- the interlaced triangles

- the cruxansata (in the centre)

- the pin of the Society, composed of cruxansata and serpent entwined, forming together "T.S.", and

- Om (or aum), the sacred syllable of the Vedas.

The seal of the Society contains all of these symbols, except aum, and thus contains, in symbolic form, the doctrines its members follow.[71]

Septenary systems

In the Theosophical view all major facets of existence manifest following a seven-fold model: "Our philosophy teaches us that, as there are seven fundamental forces in nature, and seven planes of being, so there are seven states of consciousness in which man can live, think, remember and have his being."[72]

Seven cosmic planes

The Cosmos does not consist only of the physical plane that can be perceived with the five senses, but there is a succession of seven Cosmic planes of existence, composed of increasingly subtler forms of matter-energy, and in which states of consciousness other than the commonly known can manifest. Blavatsky described the planes according to these states of consciousness. In her system, for example, the plane of the material and concrete mind (lower mental plane) is classified as different from the plane of the spiritual and holistic mind (higher mental plane). Later Theosophists like Charles Webster Leadbeater and Annie Besant classified the seven planes according to the kind of subtle matter that compose them. Since both the higher and lower mental planes share the same type of subtle matter, they regard them as one single plane with two subdivisions. In this later view the seven cosmic planes include (from spiritual to material):

- Adi (the supreme, a divine plane not reached by human beings)

- Anupadaka (the parentless, also a divine plane home of the divine spark in human beings, the Monad)

- Atmic (the spiritual plane of Man's Higher Self)

- Buddhic (the spiritual plane of intuition, love, and wisdom)

- Mental (with a higher and lower subdivisions, this plane bridges the spiritual with the personal)

- Emotional (a personal plane that ranges from lower desires to high emotions)

- Physical plane (a personal plane which again has two subdivisions the dense one perceivable by our five senses, and an etheric one that is beyond these senses)

Seven principles and bodies

Just as the Cosmos is not limited to its physical dimension, human beings have also subtler dimensions and bodies. The "Septenary Nature of Man" was described by Blavatsky in, among other works, The Key to Theosophy; in descending order, it ranges from a postulated purely spiritual essence (called a "Ray of the Absolute") to the physical body.[73]

The Theosophical teachings about the constitution of human beings talk about two different, but related, things: principles and bodies. Principles are the seven basic constituents of the universe, usually described by Mme. Blavatsky as follows:

- Physical

- Astral (later called etheric)

- Prana (or vital)

- Kama (animal soul)

- Manas (mind, or human soul)

- Buddhi (spiritual soul)

- Atma (Spirit or Self)

These Principles in Man may or may not form one or more bodies. Blavatsky's teachings about subtle bodies were few and not very systematic. In an article she described three subtle bodies:[74]

- Linga Sharira – the Double or Astral body

- Mayavi-rupa – the "Illusion-body"

- Causal Body – the vehicle of the higher Mind

The Linga Sharira is the invisible double of the human body, elsewhere referred to as the etheric body or doppelgänger and serves as a model or matrix of the physical body, which conforms to the shape, appearance and condition of his "double". The linga sarira can be separated or projected a limited distance from the body. When separated from the body it can be wounded by sharp objects. When it returns to the physical frame, the wound will be reflected in the physical counterpart, a phenomenon called "repercussion." At death, it is discarded together with the physical body and eventually disintegrates or decomposes. This can be seen over the graves like a luminous figure of the man that was, during certain atmospheric conditions.

The mayavi-rupa is dual in its functions, being: "...the vehicle both of thought and of the animal passions and desires, drawing at one and the same time from the lowest terrestrial manas (mind) and Kama, the element of desire."[74]

The higher part of this body, containing the spiritual elements gathered during life, merges after death entirely into the causal body; while the lower part, containing the animal elements, forms the Kama-rupa, the source of "spooks" or apparitions of the dead.

Therefore, besides the dense physical body, the subtle bodies in a human being are:

- Etheric body (vehicle of prana)

- Emotional or astral body (vehicle of desires and emotions)

- Mental body (vehicle of the concrete or lower mind)

- Causal body (vehicle of the abstract or higher mind)

These bodies go up to the higher mental plane. The two higher spiritual Principles of Buddhi and Atma do not form bodies proper but are something more like "sheaths".

Rounds and races

It follows from the above that to Theosophy, all Evolution is basically the evolution of Consciousness, physical-biological evolution being only a constituent part.[s] All evolutionary paths involve the serial immersion (or reincarnation) of basic units of consciousness called Monads into forms that become gradually denser, and which eventually culminate in gross physical matter. At that point the process reverses towards a respiritualization of consciousness. The experience gained in the previous evolutionary stages is retained; and so consciousness inexorably advances towards greater completeness.[t]

All individuated existence, regardless of stature, apparent animation, or complexity, is thought to be informed by a Monad; in its human phase, the Monad consists of the two highest-ordered (out of seven) constituents or principles of human nature and is connected to the third-highest principle, that of mind and self-consciousness (see Septenary above).

Theosophy describes humanity's evolution on Earth in the doctrine of Root races.[u] These are seven stages of development, during which every human Monad evolves alongside others in stages that last millions of years, each stage occurring mostly in a different super-continent—these continents are actually, according to Theosophy co-evolving geological and climatic stages.[v] At present, humanity's evolution is at the fifth stage, the so-called Aryan Root race, which is developing on its appointed geologic/climatic period.[w] The continuing development of the Aryan stage has been taking place since about the middle of the Calabrian (about 1,000,000 years ago).[x] The previous fourth Root race was at the midpoint of the sevenfold evolutionary cycle, the point in which the "human" Monad became fully vested in the increasingly complex and dense forms that developed for it. A component of that investment was the gradual appearance of contemporary human physiology, which finalized to the form known to early 21st century medical science during the fourth Root race.[y] The current fifth stage is on the ascending arc, signifying the gradual reemergence of spiritualized consciousness (and of the proper forms, or "vehicles", for it) as humanity's dominant characteristic. The appearance of Root races is not strictly serial; they first develop while the preceding Race is still dominant. Older races complete their evolutionary cycle and die out; the present fifth Root race will in time evolve into the more advanced spiritually sixth.[82]

Humanity's evolution is a subset of planetary evolution, which is described in the doctrine of Rounds, itself a subject of Theosophy's Esoteric cosmology. Rounds may last hundreds of millions of years each. Theosophy states that Earth is currently in the fourth Round of the planet's own sevenfold development.[z] Human evolution is tied to the particular Round or planetary stage of evolution—the Monads informing humans in this Round were previously informing the third Round's animal class, and will "migrate" to a different class of entities in the fifth Round.[aa]

Racial theories

Regarding the origin of the human races on earth, Blavatsky in The Secret Doctrine argued for polygenism—"the simultaneous evolution of seven human groups on seven different portions of our globe".[85]

The Secret Doctrine states:

Mankind did not issue from one solitary couple. Nor was there ever a first man—whether Adam or Yima—but a first mankind. It may, or may not, be "mitigated polygenism." Once that both creation ex nihilo—an absurdity—and a superhuman Creator or creators—a fact—are made away with by science, polygenism presents no more difficulties or inconveniences (rather fewer from a scientific point of view) than monogenism does.[86]

Blavatsky used the compounded word Root race to describe each of the seven successive stages of human evolution that take place over large time periods in her cosmology. A Root-race is the archetype from which spring all the races that form humanity in a particular evolutionary cycle. She called the current Root-race, the fifth one, "Aryan".[87]

The present Root-race was preceded by the fourth one, which developed in Atlantis, while the third Root-race is denominated "Lemurian". She described the Aryan Root-race in the following way:

The Aryan races, for instance, now varying from dark brown, almost black, red-brown-yellow, down to the whitest creamy colour, are yet all of one and the same stock—the Fifth Root-Race—and spring from one single progenitor, (...) who is said to have lived over 18,000,000 years ago, and also 850,000 years ago—at the time of the sinking of the last remnants of the great continent of Atlantis.[87]

Her evolutionary view admits a difference in development between various ethnic groups:

The occult doctrine admits of no such divisions as the Aryan and the Semite, accepting even the Turanian [as part of the same language group] with ample reservations. The Semites, especially the Arabs, are later Aryans—degenerate in spirituality and perfected in materiality.[88]

She also states that:

There are, or rather still were a few years ago, descendants of these half-animal tribes or races, both of remote Lemurian and Lemuro-Atlantean origin ... Of such semi-animal creatures, the sole remnants known to Ethnology were the Tasmanians, a portion of the Australians and a mountain tribe in China, the men and women of which are entirely covered with hair.[89]

Blavatsky's teachings talk about three separate levels of evolution: physical, intellectual, and spiritual.[90] Blavatsky states that there are differences in the spiritual evolution of the Monads (the "divine spark" in human beings), in the intellectual development of the souls, and in the physical qualities of the bodies. These levels of evolution are independent. A highly evolved Monad may incarnate, for karmic reasons, in a rather crude personality. Also, a very intellectual person may be less evolved at the spiritual level than an illiterate.

She also states that cultures follow a cycle of rising, development, degeneration, and eventually disappear. Also, according to her there is a fixed number of reincarnating souls evolving, all of which are beyond sex, nationality, religion, and other physical or cultural characteristics. In its evolutionary journey, every soul has to take birth in every culture in the world, where it acquires different skills and learns different lessons.[91]

Even though she declares that at this point of their cultural evolutionary cycle the Semites, especially the Arabs, are "degenerate in spirituality and perfected in materiality", she also stated that there were wise and initiated teachers among the Jews and the Arabs,[92] some of them were Blavatsky's teachers early in her life.

Blavatsky does not claim that the present Aryan Root-race is the last and highest of them all. The Indo-European races will also eventually degenerate and disappear, as new and more developed races and cultures develop on the planet:

Thus will mankind, race after race, perform its appointed cycle-pilgrimage. Climates will, and have already begun, to change, each tropical year after the other dropping one sub-race, but only to beget another higher race on the ascending cycle; while a series of other less favoured groups—the failures of nature—will, like some individual men, vanish from the human family without even leaving a trace behind.

Such is the course of Nature under the sway of KARMIC LAW: of the ever present and the ever-becoming Nature.[93]

The first aim of the Theosophical Society she founded is "To form a nucleus of the Universal Brotherhood of Humanity, without distinction of race, creed, sex, caste or colour", and her writings also include references emphasizing the unity of humanity: "all men have spiritually and physically the same origin" and that "mankind is essentially of one and the same essence".[94]

Cranston quoted Blavatsky saying that in reality there is no inferior or low-grade races because all of it are one common humankind.[95] A view which is also evident in the Secret Doctrine.[ab]

Influence

Following

During the 1920s the Theosophical Society Adyar had around 7,000 members in the USA.[97] There also was a substantial following in Asia. According to a Theosophical source, the Indian section in 2008 was said to have around 13,000 members while in the US the 2008 membership was reported at around 3,900.[98]

Very few scientists have been Theosophists, though some notable exceptions have included the chemists William Crookes and Ernest Lester Smith who were elected members of the British Royal Society and I. K. Taimni a professor of Chemistry at the Allahabad University in India.[ac]

Western esotericism

Anthroposophy

Rudolf Steiner, head of the German branch of the Theosophical Society in the early part of the 20th-century, disagreed with the Adyar-based international leadership of the Society over several doctrinal matters including the so-called World Teacher Project that showed the desire of some members of the Theosophical Society to set up Krishnamurti as the reincarnation of the Maitreya. Steiner left the Theosophical Society in 1913 to further develop his independent investigations into the spiritual world, which he called Anthroposophy through a new organization, the Anthroposophical Society; the great majority of German-speaking Theosophists joined him in the new group.

Ariosophy

Austrian/German ultra-nationalist Guido von List and his followers such as Lanz von Liebenfels, selectively mixed Theosophical doctrine on the evolution of Humanity and on Root races with nationalistic and fascist ideas; this system of thought became known as Ariosophy, a precursor of Nazism.[ad] The central importance of "Aryan" racism in Ariosophy, albeit compounded by occult notions deriving from theosophy, may be traced to the racial concerns of Social Darwinism in Germany.[101]

New Age movement

The present-day New Age movement is said to be based to a considerable extent on the Theosophical tenets and ideas presented by Blavatsky and her contemporaries. "No single organization or movement has contributed so many components to the New Age Movement as the Theosophical Society. ... It has been the major force in the dissemination of occult literature in the West in the twentieth century."[102][ae] Other organizations loosely based on Theosophical texts and doctrines include the Agni Yoga, and a group of religions based on Theosophy called the Ascended Master Teachings: the "I AM" Activity, The Bridge to Freedom and The Summit Lighthouse, which evolved into the Church Universal and Triumphant.

Asian reform movements

The Theosophical Society had a major influence on Buddhist modernism[8] and Hindu reform movements, and the spread of those modernised versions in the west.[8]

Indian Independence Movement

Some early members of the Theosophical Society were closely linked to the Indian independence movement, including Allan Octavian Hume, Annie Besant and others. Hume was particularly involved in the founding of the Indian National Congress.

Buddhist Modernism

Along with Olcott and Anagarika Dharmapala, Blavatsky was instrumental in the Western transmission and revival of Theravada Buddhism.[104][105][106]

Art, music and literature

Artists and authors who investigated Theosophy include Talbot Mundy, Charles Howard Hinton, Geoffrey Hodson, James Jones,[107] H. P. Lovecraft, Robert E. Howard, Clark Ashton Smith, Sun Ra, Lawren Harris and L. Frank Baum. Composer Alexander Scriabin was a Theosophist whose beliefs influenced his music, especially by providing a justification or rationale for his chromatic language. Scriabin devised a quartal synthetic chord, often called his mystic chord, and before his death Scriabin planned a multimedia work to be performed in the Himalayas that would bring about the armageddon; "a grandiose religious synthesis of all arts which would herald the birth of a new world."[108] This piece, Mysterium, was unfinished when he died in 1915.

Blavatsky presented her book The Voice of the Silence, The Seven gates, Two Paths to Leo Tolstoy. In his works, Tolstoy used the dicta from the theosophical journal Theosophischer Wegweiser.[109] In his diary, he wrote on 12 February 1903, "I am reading a beautiful theosophical journal and find many common with my understanding."[110]

Leonid Sabaneyev, in his book Reminiscences about Scriabin (1925), wrote that The Secret Doctrine and journals "Bulletin of theosophy" constantly were on Scriabin's work table.[111] Scriabin reread The Secret Doctrine very carefully and marked the most important places by a pencil.[112][af]

Criticism

Blavatsky was influential on spiritualism and related subcultures: "The western esoteric tradition has no more important figure in modern times."[113] She wrote prolifically, publishing thousands of pages and debate continues about her work. She taught about very abstract and metaphysical principles, but also sought to denounce and correct superstitions that, in her view, had grown in different esoteric religions. Some of these statements are controversial. For example, she quotes Anna Kingsford and Edward Maitland's book The Perfect Way.[114] "It is 'Satan who is the God of our planet and the only God', and this without any metaphorical allusion to its wickedness and depravity," wrote Blavatsky, in The Secret Doctrine. "For he is one with the Logos."[115] He is whom "every dogmatic religion, preeminently the Christian, points out as [...] the enemy of God, [... but is] in reality, the highest divine Spirit—Occult Wisdom on Earth. [...] Thus, the Latin Church [... and] the Protestant Church [... both] are fighting against divine Truth, when repudiating and slandering the Dragon of Esoteric Divine Wisdom. Whenever they anathematize the Gnostic Solar Chnouphis, the Agathodaemon Christos, or the Theosophical Serpent of Eternity, or even the Serpent of Genesis."[116] In this reference Blavatsky explains that he whom the Christian dogma calls Lucifer was never the representative of the evil in ancient myths but, on the contrary, the light-bringer (which is the literal meaning of the name Lucifer). According to Blavatsky the church turned him into Satan (which means "the opponent") to misrepresent pre-Christian beliefs and fit him into the newly framed Christian dogmas. A similar view is also shared by some Christian Gnostics, ancient and modern.

Throughout much of Blavatsky's public life her work drew harsh criticism from some of the learned authorities of her day, as for example when she said that the atom was divisible.[117]

Max Müller, the renowned philologist and orientalist, was scathing in his criticism of Blavatsky's Esoteric Buddhism. Whilst he was willing to give her credit for good motives, at least at the beginning of her career, in his view she ceased to be truthful both to herself and to others with her later "hysterical writings and performances". Müller felt he had to speak out when he saw the Buddha being "lowered to the level of religious charlatans, or his teaching misrepresented as esoteric twaddle". There is a nothing esoteric or secretive in Buddhism, he wrote, in fact the very opposite. "Whatever was esoteric was ipso facto not Buddha's teaching; whatever was Buddha's teaching was ipso facto not esoteric".[118][ag] Blavatsky, it seemed to Müller, "was either deceived by others or carried away by her own imaginations" and that Buddha was "against the very idea of keeping anything secret".[119]

Critics pronounced her claim of the existence of masters of wisdom to be utterly false, and accused her of being a charlatan, a false medium,[ah] evil, a spy for the Russians, a smoker of cannabis, a plagiarist, a spy for the English, a racist,[120] and a falsifier of letters. Most of the accusations remain undocumented.[121][122][123]

In The New York Times Edward Hower wrote, "Theosophical writers have defended her sources vehemently. Skeptics have painted her as a great fraud."[124] The authenticity and originality of her writings were questioned. Blavatsky was accused of having plagiarized a number of sources, copying the texts crudely enough to misspell the more difficult words.[125]

In the 1885 Hodgson Report to the Society for Psychical Research (SPR), Richard Hodgson concluded that Blavatsky was a fraud.[ai] However, in 1986, the SPR published a critique by handwriting expert Vernon Harrison,[126][122] "which discredited crucial elements" of Hodgeson's case against Blavatsky, nevertheless, "Theosophists have overinterpreted this as complete vindication," wrote Johnson, "when in fact many questions raised by Hodgson remain unanswered."[127]

René Guénon wrote a detailed critique of Theosophy titled Theosophy: history of a pseudo-religion (1921). Guénon claimed that Blavatsky had acquired all her knowledge naturally from other books, not from any supernatural masters. Guénon pointed out that Blavatsky spent a long time visiting a library at New York where she had easy access to the works of Jacob Boehme, Eliphas Levi, the Kabbalah and other Hermetic treatises. Guénon also wrote that Blavatsky had borrowed Kanjur and Tanjur translations by orientalist Sándor Kőrösi Csoma which were published in Asiatic Researches.[128][aj]

Robert Todd Carroll wrote, in The Skeptic's Dictionary, that Blavatsky used trickery into deceiving others into thinking she had paranormal powers. Carroll wrote that Blavatsky had "faked the materialization of a tea cup and saucer" as well as written messages from her masters herself, "presumably to enhance her credibility".[129] Mattias Gardell in Gods of the blood has documented how the Aryan race ideas of Blavatsky and other Theosophists have influenced esoteric racialist groups such as Ariosophy and scientific racism.[130]

Randi, a stage magician and paranormal investigator, calls her a fraud in An Encyclopedia of Claims, Frauds, and Hoaxes of the Occult and Supernatural. "What is known to be true is that she went from being a piano teacher to a circus bareback rider to a spirit medium, and she eventually was employed by the spirit medium Daniel Dunglas Home as an assistant, where she doubtless learned some of the tricks of the trade," wrote Randi, and believed that her "tales are highly doubtful."[35]

Works

Her works include:

- Isis unveiled. J.W. Bouton. 1877. OCLC 7211493.

- From the Caves and Jungles of Hindostan. Floating Press. 1880. ISBN 1-77541-603-8.

- The Voice of the Silence. Theosophy Co. (India) Ltd. 1933 [1889]. OCLC 220858481.

- Nightmare tales. London, Theosophical publishing society. 1892. OCLC 454984121.

Many articles have been compiled in 15 volumes of De Zirkoff, Boris; Eklund, Dara (eds.). Collected writings. Wheaton, Il: Theosophical Publishing House. ISBN 0835671887. An alternative link is: http://collectedwritings.net

See also

- Schola Philosophicae Initiationis

- Tulpa

- Violet Tweedale, close associate of Blavatsky.

- Western esotericism

Notes

- ^ Isis Unveiled was "extensively plagiarized from standard works on occultism and Hermeticism".[5]

- ^ In the letter from 1 March 1882 Blavatsky wrote to Prince A.M. Dondukov-Korsakov: "My maternal great-grandfather, Prince Pavel Vasilievich Dolgoruky, had an unusual library. There were thousands books for alchemy, magic and other occult sciences. I have read it with great interest before fifteen"[19]

- ^ Randi wrote that "while she was operating as a spirit medium in Cairo, [...] a great commotion arose when a long cotton glove stuffed with cotton was discovered in the séance room, and" Blavatsky "wisely departed hastily for Paris."[35]

- ^ According to Randi, she "began performing séances for wealthy patrons there."[35]

- ^ For more about Blavatsky's and Olcott's relationship, as well as the Esoteric Section of the Theosophical Society, to the rival Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor, Max Théon, and Emma Hardinge Britten see [37] and Godwin, Chanel & Deveney (1995, pp. 6–9, 12, 25, 35–36, 43, 46–48, 52–62).

- ^ According to James Randi she died from Bright's disease.[35]

- ^ "Article I: Constitution: 4. The Theosophical Society is absolutely unsectarian, and no assent to any formula of belief, faith or creed shall be required as a qualification of membership; but every applicant and member must lie in sympathy with the effort to create the nucleus of an Universal Brotherhood of Humanity."[44]

- ^ Societies and Organizations include, but are not limited to: the Theosophical Society Adyar, the Theosophical Society Pasadena, and the United Lodge of Theosophists.

- ^ Some of the later works have become the focus of, or have contributed to, lively discussion among leading proponents of theosophy, and on occasion have led to serious doctrinal disputes. See Neo-Theosophy.

- ^ Blavatsky stated that in practical terms, her Theosophical exposition concerned itself only "with our planetary System and what is visible around it".[52] "Bear in mind that the Stanzas given treat only of the Cosmogony of our own planetary System and what is visible around it, .... The secret teachings with regard to the Evolution of the Universal Kosmos cannot be given, .... Moreover the Teachers say openly that not even the highest Dhyani-Chohans have ever penetrated the mysteries beyond those boundaries that separate the milliards of Solar systems from the 'Central Sun,' as it is called. Therefore, that which is given, relates only to our visible Kosmos, ...." However, some of her statements have been unclear or contradictory on the subject and she often stressed, "Everything in the Universe follows analogy. 'As above, so below'".[53]

- ^ "Faith is a word not to be found in theosophical dictionaries: we say knowledge based, on observation and experience. There is this difference, however, that while the observation and experience of physical science lead the Scientists to about as many 'working' hypotheses as there are minds to evolve them, our knowledge consents to add to its lore only those facts which have become undeniable, and which are fully and absolutely demonstrated. We have no two beliefs or hypotheses on the same subject."[54]

- ^ "It is the uninterrupted record covering thousands of generations of Seers whose respective experiences were made to test and to verify the traditions passed orally by one early race to another, of the teachings of higher and exalted beings, who watched over the childhood of Humanity. That for long ages, the 'Wise Men' of the Fifth Race, ... had passed their lives in learning, not teaching. ... By checking, testing, and verifying in every department of nature the traditions of old by the independent visions of great adepts; i.e., men who have developed and perfected their physical, mental, psychic, and spiritual organizations to the utmost possible degree. No vision of one adept was accepted until it was checked and confirmed by the visions—so obtained as to stand as independent evidence—of other adepts, and by centuries of experiences."[55]

- ^ "The Society is a philanthropic and scientific body for the propagation of the idea of brotherhood on practical instead of theoretical lines. The Fellows may be Christians or Mussulmen, Jews or Parsees, Buddhists or Brahmins, Spiritualists or Materialists, it does not matter; but every member must be either a philanthropist, or a scholar, a searcher into Aryan and other old literature, or a psychic student. In short, he has to help, if he can, in the carrying out of at least one of the objects of the programme."[56]

- ^ "An Omnipresent, Eternal, Boundless, and Immutable PRINCIPLE on which all speculation is impossible, since it transcends the power of human conception and could only be dwarfed by any human expression or similitude."[58]

- ^ "The expansion 'from within without'..., does not allude to an expansion from a small centre or focus, but, without reference to size or limitation or area, means the development of limitless subjectivity into as limitless objectivity. ...It implies that this expansion, not being an increase in size—for infinite extension admits of no enlargement—was a change of condition." Manifest existence is often called "Illusion" in Theosophy, owing to its conceptual and actual differentiation from the only Reality.[60]

- ^ "Everything in the Universe, throughout all its kingdoms, is CONSCIOUS: i.e., endowed with a consciousness of its own kind and on its own plane of perception. We men must remember that because we do not perceive any signs—which we can recognise—of consciousness, say, in stones, we have no right to say that no consciousness exists there. There is no such thing as either 'dead' or 'blind' matter, as there is no 'Blind' or 'Unconscious' Law".[61]

- ^ Blavatsky states that each complete cycle lasts 311,040,000,000,000 years.[64]

- ^ Blavatsky, Helena P. (1893). The secret doctrine: the synthesis of science, religion, and philosophy. Vol. 1 (Original from Harvard University ed.). Theosophical Publishing Society. pp. 129–130, 523, 573–4.

- ^ The terms "spirit" and "matter" have uncommon meanings in Theosophy, standing in as two aspects of the single, absolute reality. More accurate terms according to Blavatsky would be the notions of "subject" (spirit) and "object" (matter). [75] "But once that we pass in thought from this (to us) Absolute Negation, duality supervenes in the contrast of Spirit (or consciousness) and Matter, Subject and Object. Spirit (or Consciousness) and Matter are, however, to be regarded, not as independent realities, but as the two facets or aspects of the Absolute"; [76] "Matter is Spirit, and vice versa ... the Universe and the Deity which informs it are unthinkable apart from each other". [Emphasis in original]

- ^ Information about the Monads in this section is almost exlusively based on two chapters in The Secret Doctrine: "Explanations concerning the Globes and the Monads" and "Gods, Monads, and Atoms".[77] They cover the complicated Monad doctrine in some detail.

- ^ The concept of race in this case and Theosophy in general has a different meaning than the one given by early 21st-century Anthropology and Sociology. One of the reasons for the "Root" appelation is in order to account for constituent evolutionary paths called "sub-races".

- ^ "Our globe is subject to seven periodical entire changes which go pari passu with the races ... three occasioned by the change in the inclination of the earth's axis ... such changes in the axial direction ... are always followed by [climatic] vicissitudes .... Occult data show that even since the time of the regular establishment of the Zodiacal calculations in Egypt, the poles have been thrice inverted."[78]

- ^ "Since ... Humanity appeared on this Earth, there have already been four such axial disturbances; when the old continents—save the first one—were sucked in by the oceans, other lands appeared, and huge mountain chains arose where there had been none before. The face of the Globe was completely changed each time".[79]

- ^ "Now our Fifth Root-Race has already been in existence—as a race sui generis and quite free from its parent stem—about 1,000,000 years". [Emphasis in original].[80]

- ^ "And when we say human, this does not apply merely to our terrestrial humanity, but to the mortals that inhabit any world, i.e., to those Intelligences that have reached the appropriate equilibrium between matter and spirit, as we have now, since the middle point of the Fourth Root Race of the Fourth Round was passed."[81]

- ^ "Everything in the metaphysical as in the physical Universe is septenary. Hence every sidereal body, every planet, whether visible or invisible, is credited with six companion globes. ... The evolution of life proceeds on these seven globes or bodies from the 1st to the 7th in Seven ROUNDS or Seven Cycles. ... Our Earth ... has to live, as have the others, through seven Rounds. During the first three, it forms and consolidates; during the fourth it settles and hardens; during the last three it gradually returns to its first ethereal form: it is spiritualised, so to say. ... Its Humanity develops fully only in the Fourth—our present Round. Up to this fourth Life-Cycle, it is referred to as 'humanity' only for lack of a more appropriate term. ... During the three Rounds to come, Humanity, like the globe on which it lives, will be ever tending to reassume its primeval form ... Man tends to become a God and then—GOD, like every other atom in the Universe."[83]

- ^ "As shown, the [now human] MONAD had passed through, journeyed and been imprisoned in, every transitional form throughout every kingdom of nature [mineral, vegetable, and animal] during the three preceding Rounds."[84]

- ^ "In this manner the reason for division of humankind into higher and lower races is obsolete and a erroneous belief."[96][failed verification – see discussion]

- ^ Alvin Boyd Kuhn wrote his thesis, Theosophy: A Modern Revival of Ancient Wisdom, on the subject—the first instance in which an individual obtained his doctorate with a thesis on Theosophy.[99]

- ^ The Thule Society was one of several German occult groups that later drew on Ariosophy to promote their so-called Aryan supremacy doctrine. This provided a direct link between occult racial theories and the racial ideology of Hitler and the emerging Nazi party.[100]

- ^ The "Chronology of the New Age Movement" in New Age Encyclopedia begins with the formation of the Theosophical Society in 1875.[103] See Lewis & Melton 1992, xi.

- ^ For more about how Scriabin was influenced by Blavatsky, see Adamenko, Victoria (2007) [2006]. Neo-mythologism in music : from Scriabin and Schoenberg to Schnittke and Crumb. Interplay series. Vol. 5. Hillsdale, NY: Pendagon Press. pp. 152–154. ISBN 9781576471258.

- ^ For Sinnett's response and Müller's rejoinder, see Sinnett 1893 and Müller 1893b.

- ^ According to Randi, her "messages were often in the form of small bits of paper that floated down from the ceiling above her. She attracted many prominent persons to the movement by her performance of these effective diversions."[35]

- ^ According to Randi, the SPR exposed her techniques and equipment that "were shown to be the means by which she produced the written messages from her mahatmas, and it was revealed that she had deceived a disciple by hiring an actor wearing a dummy bearded head and flowing costume to impersonate" Koot Hoomi.[35]

- ^ See Kőrösi Csoma, Alexander (1836). Asiatic researches, or, Transactions of the society, instituted in Bengal, for inquiring into the history, and antiquities, the arts and sciences, and literature of Asia. 20. Calcutta: G. H. Huttmann: 41–93, 393–552, 553–585. OCLC 10257286.

{{cite journal}}: External link in|volume=|title=(help)

References

- ^ Greer 2003, p. 67.

- ^ The Theosophist & Oct., 1879.

- ^ 1891 England Census, showing a household including "Constance Wachtmeister Manager of Publishing Office; G.R.S. Mead, Author Journalist; Isabel Oakley, Millener; Helena Blavatsky, Authoress; and others"

- ^ Sedgwick 2004, p. 44; Campbell 1980, pp. 32–34.

- ^ Sedgwick 2004, p. 44.

- ^ Suzuki, D. T. (August 1965) The Middle Way, P. 90

- ^ Gandhi 1927, pp. 57–58.

- ^ a b c d MacMahan 2008.

- ^ MacMahan 2008, p. 98; Gombrich 1996, pp. 185–188; Fields 1992, pp. 83–118.

- ^ Фадеев. Ч.I., p. 129[full citation needed]

- ^ Некрасова. VIII. С. 560–1[full citation needed]

- ^ a b c d e Davenport-Hines 2011.

- ^ Sinnett 1886, p. 28.

- ^ Желиховская. Е. П. Блаватская. II., p. 246.

- ^ Zhelihovsky. Helena Petrovna Blavatsky // Lucifer. p. 204; The Theosophist. p. 240

- ^ Кайдаш.

- ^ Блаватская Елена Петровна // Русская философия: словарь/Под общ. ред. М. А. Маслина / В. В. Сапов. – М.: Республика, 1995

- ^ a b Кранстон, 1999 & 50–51.

- ^ Блаватская Е. П. Письма друзьям и сотрудникам. Сборник. Перев. С англ. – М., 2002. – С. 249.

- ^ Фадеев. Ч. I. С. 194–199[full citation needed]; Желиховская. Мое отрочество. Ч II. Гл. XI

- ^ a b c Писарева.

- ^ Кранстон 1999, p. 56.

- ^ Goodrick-Clarke 2004, p. 3.

- ^ Richard-Nafarre 1991, p. 66.

- ^ Johnson 1994, p. 23.

- ^ Neff 1937, ch. 5.

- ^ a b See Дроздов. С. 364–366, 368–369[full citation needed]

- ^ Фадеев. Ч. II. C. 77–79[full citation needed]; Желиховская. Моё отрочество. Ч. II. Гл. XIV. С. 274

- ^ Кранстон 1999, pp. 638–639.

- ^ Блаватская, Елена П. (2002). "Письмо А. М. Дондукову-Корсакову от 1 марта 1882 года". Письма друзьям и сотрудникам. Р.Ш Ахунов, Т.В. Корженьянц. Москва: Сфера. p. 250. ISBN 5-93975-062-1.

- ^ a b Boase 1908. Cite error: The named reference "FOOTNOTEBoase1908" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Sinnett 1886, pp. 57–59.

- ^ Blavatsky 1888a, pp. 238, 411; Blavatsky 1888b, pp. 617, 627–628, cited in Evans-Wentz (2000, p. 7)

- ^ Evans-Wentz 2000, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e f g Randi 2006.

- ^ a b c Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology 2001, p. 1557.

- ^ Blavatsky 1877b, p. 308, quoted in Godwin, Chanel & Deveney (1995, p. 292)

- ^ Murphet 1988.

- ^ New York Times & 1878-07-09.

- ^ Barker 1923.

- ^ George, Marcia Ann. "Helena Blavatsky, 19th Century Mystic Extraordinaire". Who Are You, Madame Blavatsky? A Film by Karine Dilanyan. Archived from the original on 30 April 2006. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ The Times 1891.

- ^ Blavatsky 2002, pp. 39–41.

- ^ Olcott 1891.

- ^ Blavatsky 1877a, x–xi.

- ^ Blavatsky 1918, p. 304: "Theosophia"

- ^ Blavatsky 1962, p. 1–4.

- ^ Blavatsky 1918, pp. 304–305: "Theosophists"

- ^ "Blavatsky Articles". Blavatsky.net. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ Melton 1990, pp. xxv–xxvi.

- ^ Wakoff 1998.

- ^ Blavatsky 1888a, p. 13.

- ^ Blavatsky 1888a, p. 177.

- ^ Blavatsky 2002, pp. 3–4, 7–12, 87.

- ^ Blavatsky 1888a, pp. xxxviii, 272–273.

- ^ Blavatsky 2002, p. 19.

- ^ Zirkoff 1968.

- ^ a b Blavatsky 1888a, p. 14.

- ^ Blavatsky 1888a, pp. 35–85.

- ^ Blavatsky 1888a, pp. 62–63.