Red Line (MBTA)

| Template:MBTA infobox header | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Red Line train leaving Charles/MGH station outbound over the Longfellow Bridge | |||

| Overview | |||

| Owner | Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority | ||

| Locale | Boston, Massachusetts | ||

| Termini | |||

| Stations | 22 | ||

| Service | |||

| Type | Rapid transit | ||

| Services | 2 | ||

| Operator(s) | Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority | ||

| Rolling stock | Type 1, Type 2, Type 3 Red Line | ||

| Daily ridership | 272,684 (2013)[1] | ||

| History | |||

| Opened | March 23, 1912 | ||

| Technical | |||

| Line length | 11.5 miles (18.5 km) Alewife–Ashmont 17.5 miles (28.2 km) Alewife–Braintree 22.5 miles (36.2 km) total | ||

| Character | Subway, Grade-separated ROW | ||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) | ||

| Electrification | Third rail | ||

| |||

The Red Line is a rapid transit line operated by the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA). It runs roughly northwest-to-southeast across Cambridge and Davis Square in Somerville – from Alewife in North Cambridge to Kendall/MIT in Kendall Square – with a connection to commuter rail at Porter. It then crosses over the Longfellow Bridge into downtown Boston, where it connects with the Green Line at Park Street, the Orange Line at Downtown Crossing, the Silver Line at South Station, as well as Amtrak and commuter rail at the South Station surface terminal before passing through South Boston and Dorchester. South of JFK/UMass in Dorchester, it splits into two branches terminating at Braintree and Ashmont stations; transfers to commuter rail are again possible at JFK/UMass, Quincy Center, and Braintree. From Ashmont, passengers may continue to Mattapan via the Ashmont–Mattapan High Speed Line, a 2.6-mile (4.2 km) light rail line.

All Red Line stations are handicapped accessible except Wollaston on the Braintree branch, and Valley Road on the Ashmont-Mattapan High Speed Line. As of 2015[update], MBTA is designing renovations to make Wollaston fully accessible.[2]

History

Cambridge Tunnel

The Red Line was the last of the four original Boston subway lines (the others being the Green, Orange, and Blue Lines, opened in 1897, 1901, and 1904, respectively) to come into being.

Construction of the Cambridge Tunnel, connecting Harvard Square to Boston, was delayed by a dispute over the number of intermediate stations to be built along the new line. Cambridge residents, led by Mayor Wardwell, wanted at least five stations built along the line, while suburbanites interested in faster through travel argued for only a single intermediate station, at Central Square. The contending groups finally compromised on two intermediate stations, at Central and Kendall Squares, allowing construction to start in 1909.[further explanation needed][3]: 41

The section from Harvard (and new maintenance facilities at Eliot Yard) to Park Street was opened by the Boston Elevated Railway (BERy) on March 23, 1912. At Harvard, a prepayment station provided easy transfer to streetcars routed through what is now the Harvard Bus Tunnel. From Harvard, the Cambridge Tunnel traveled beneath Massachusetts Avenue to Central Square station. It then continued under Mass. Ave until Main Street, which it followed to reach Kendall station. The underground line then rose onto the Longfellow Bridge, using a central right-of-way which had been reserved during the bridge's 1900–1906 construction. On the Boston side, the line briefly became an elevated railway, maintaining its elevation at Charles/MGH station as vehicle lanes descended beneath it to Charles Circle; the tracks then immediately entered a tunnel beneath Beacon Hill, leading to new lower-level platforms at Park Street Under.

Dorchester Tunnel and Extension

The Dorchester Tunnel to Washington Street and South Station Under opened on April 4, 1915 and December 3, 1916, with transfers to the Washington Street Tunnel and Atlantic Avenue Elevated, respectively. Further extensions opened to Broadway on December 15, 1917 and Andrew on June 29, 1918, both prepayment stations for streetcar transfer. The Broadway station included an upper level with its own tunnel for streetcars, which was soon abandoned in 1919 due to most lines being truncated to Andrew. The upper level at Broadway was later incorporated into the mezzanine.

Next came the Dorchester Extension (now the Ashmont Branch), following a rail right-of-way created in 1870 by the Shawmut Branch Railroad. In 1872, the right-of-way was acquired by the Old Colony Railroad to connect their main line at Harrison Square with the Dorchester and Milton Branch Railroad, running from the Old Colony at Neponset, west to what is now Mattapan station. The New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad succeeded the Old Colony in operating the branch, but passenger service ceased on September 4, 1926, in anticipation of the construction of the BERy's Dorchester Extension.[4]

The BERy opened the first phase of the Dorchester Extension, to Fields Corner station, on November 5, 1927, south from Andrew, then southeast to the surface and along the west side of the Old Colony mainline in a depressed right-of-way. Columbia and Savin Hill stations were built on the surface at the sites of former Old Colony stations. The remainder of the extension opened to Ashmont and Codman Yard on September 1, 1928, and included Shawmut station, where there had been a surface Old Colony station, but where the new rapid transit station was placed underground. The first phase of the Ashmont–Mattapan High Speed Line opened on August 26, 1929, using the rest of the Shawmut Branch right-of-way, including Cedar Grove station, and part of the old Dorchester and Milton Branch.

MBTA era and branding

Following the completion of the Dorchester Extension, the line became known as the Cambridge-Dorchester Tunnel. It was marked on maps as "Route 1". After taking over operations in August 1964, the MBTA began rebranding many elements of Boston's public transportation network. On August 26, 1965, the four rapid transit lines were assigned colored names related to their history and geography. On August 26, 1965, the four rapid transit lines received color designations as part of a systemwide rebranding by the newly formed MBTA. The Cambridge-Dorchester Tunnel became the Red Line because crimson is the official color of Harvard University, then the northern terminus of the line.[5][6][7]

In 1968, letters were assigned to the south branches, "A" for Quincy (planned to extend to South Braintree) and "C" for Ashmont. "B" was probably reserved for a planned branch from Braintree to Brockton. As new rollsigns were made, this lettering was phased out. In 1994, new electronic signs included a different labeling, "A" for Ashmont, "B" for Braintree and "C" for Alewife.[8]

South Shore Line

On July 28, 1965, the MBTA signed an agreement with the New Haven Railroad to purchase 11 miles (18 km) of the former Old Colony mainline from Fort Point Channel to South Braintree in order to construct a new rapid transit line along the corridor. The line was expected to be completed within two years. The agreement also provided for the MBTA to subsidize commuter service on the railroad's remaining commuter rail lines for $1.2 million annually.[5][9] Original plans called for the South Shore Line to be largely independent of the existing Red Line, with either a northern terminus at the surface level at South Station or a tunnel leading to a stub-end terminal between Post Office Square and State Street.[10] However, it was later decided to have the line be a new southern branch of the Red Line.

The first section of the South Shore Line opened on September 1, 1971, branching from the original Red Line at a flying junction north of Columbia (now JFK/UMass). It ran along the west side of the Old Colony rail right-of-way (which has since been reduced to one track), crossing to the east side north of Savin Hill. The northernmost station was North Quincy, with others at Wollaston and Quincy Center.

Braintree Extension

Beyond Quincy Center, the Braintree Extension runs southward to Braintree, opened March 22, 1980, via an intermediate stop at Quincy Adams which opened on September 10, 1983. The extension was part of the massive 1965 extension plan, although it was delayed due to questions over station siting in Braintree.[11] The Boston Transportation Planning Review, published in 1969, proposed North Braintree and South Braintree stations following the Quincy Center station.

Several outlying sections of the MBTA subway system, including Quincy Adams and Braintree, originally charged a double fare to account for the additional costs of running service far from downtown. Passengers paid two fares to enter at the stations, and an exit fare when leaving the station. Double fares on the Braintree extension, the last on the system, were discontinued in 2007 as part of a wider fare restructuring.[12]

Northwest Extension

The first part of the Northwest Extension, the relocation of Harvard station, was finished on September 6, 1983. During construction, several temporary stations were built at Harvard Square. Eliot Yard was demolished: Harvard's Kennedy School of Government now sits inside its retaining walls. Extensions to Porter and Davis on December 8, 1984 and to Alewife on March 30, 1985 brought the line to its current terminus. During the expansion, the MBTA pioneered an investment in the "Arts on the Line" public art program.

This extension had been scaled back from an original plan to extend the line from Harvard Square to Route 128 in Lexington via the former B&M/MBTA Lexington Branch railroad right-of-way. That plan had been supported by the Town of Lexington, but was scuttled by fierce anti-urban sentiment in parts of Arlington. The right-of-way on which the extension would have been built was developed into the Minuteman Bikeway. Arlington residents now regret the anti-subway push and although their fear of crime increase was over reacting (crime in arlington near alwife increased 1% house prises tripled.

Recent history

Platforms on older stations were lengthened mostly in the 1980s to allow six-car trains, which first ran January 21, 1988.[13] (The Northwest Extension and the South Shore Line were built with 6-car platforms). JFK/UMass (then called Columbia) was the first to be modified, in 1970, followed by Ashmont and Shawmut in 1981. Between 1984 and 1987, the remaining stations on the original Cambridge-Dorchester Line were rebuilt or modified.[13] In stations like Central and Downtown Crossing, the renovation is apparent where the new architecture is different from the old.

A second Red Line platform opened at JFK/UMass on December 14, 1988, allowing Braintree Branch trains to stop at the station. Since then, the configuration of the line has remained essentially static. In January 2012, the state's Central Transportation Planning staff released a conceptual plan for widening the Southeast Expressway, which would involve completely rearranging JFK/UMass station. The Red Line would be reduced to two tracks sharing a single platform, similar to the arrangements at Andrew, and the junction between the Ashmont and Braintree branches would be streamlined and moved to just south of the station. This would allow for a second commuter rail track through the station, allowing more trains to stop and eliminating a major bottleneck for the Old Colony Lines and the Greenbush Line.[14]

A $255 million project, which started in Spring 2013, will replace structural elements of the Longfellow Bridge, which carries the line across the Charles River between the Charles/MGH and Kendall/MIT stations. The project will require at least 25 weekend shutdowns, including temporary relocation of the tracks (substitute bus shuttle service will be provided). All outbound roadway traffic will be detoured from the bridge for the three years of construction. The estimated completion date has been pushed back to late 2018.[15] The rebuilt bridge will have widened sidewalks and bike lanes.[16][17]

On December 10, 2015, a Red Line train in revenue service traveled from Braintree to North Quincy without an operator in the cab before it was stopped by cutting power to the third rail. The MBTA initially said that the train appeared to have been tampered with and the incident was not an accident, but later determined operator error to have been the cause.[18]

Winter issues and resiliency work

During the unusually brutal winter of 2014–15, the entire MBTA system was shut down on several occasions by heavy snowfalls. The aboveground sections of the Orange and Red lines were particularly vulnerable due to their exposed third rail, which iced over during storms. When a single train stopped due to power loss, other trains soon stopped as well; without continually running trains pushing snow off the rails, the lines were quickly covered in snow. (Because the Blue Line was built with overhead lines on its surface section due to its proximity to corrosive salt air, it was not subject to icing issues.)

During 2015, the MBTA implemented its $83.7 million Winter Resiliency Program, much of which focused on preventing similar issues with the Orange and Red lines. The section of the Braintree Branch between JFK/UMass and Wollaston had old infrastructure and is largely built on an embankment, rendering it more vulnerable. New third rail with heaters and a different metal composition to reduce wear was installed along with snow fences and switch heaters.[19][20] The work required bustitution of the line from JFK/UMass to North Quincy on many weeknights.[21] The program did not include work south of Wollaston.[19]

In July 2016, the MBTA Fiscal and Management Control Board approved a $18.5 million contract to complete work along the remainder of the southern branches. The work includes all remaining third rail replacement, track work between Fields Corner and Savin Hill, signal system work between North Quincy and Braintree, and track replacement at Quincy Center, Quincy Adams, and Braintree. The work will be completed in the second half of 2016.[22]

Operations and signaling

The line used trip-stop wayside signaling for the Ashmont and Harvard branches until the mid-1980s, while the Braintree Branch was one of the earliest examples of Automatic Train Control (ATC).[where?] The Alewife Branch was built with ATC, at which point the remainder of the line was upgraded to ATC as well. The line was under local control at towers until 1985, when an electromechanical panel was completed at the 45 High Street control room. This was replaced in the late 1990s with a software-controlled Automatic Train Supervision, using a product by Union Switch & Signal, subcontracted to Syseca Inc. (now ARINC), at a new control room at 45 High Street. Subsequent revisions to the system were made internally at the MBTA.[citation needed]

The shortest scheduled headway run on the line was most likely the 1+3⁄4 minute interval in the schedule published in 1928. Ridership peaked around 1947, when passenger counters logged over 850 people per four-car train during peak periods. The newer ATC signaling was designed to higher safety standards, but the block layout in the downtown area reduced the capacity by 50% over the previous wayside signaling system. The net loss of capacity measured in cars per hour has not been rectified, although at the same time the platforms were lengthened to run six-car trains, which are now operated on a longer headway. The obsolete "fixed block signaling system" installed along sections of the Red Line maintains fixed distance separations between trains based on worst-case (highest speed) assumptions. When trains run at less than full speed for any reason (such as crowded conditions, track maintenance, or weather conditions), the effective carrying capacity of passengers per hour is markedly reduced. Delays in one part of the system may be propagated throughout the entire line, especially during rush hours.[23]

During snowstorms, the MBTA runs an empty train during non-service hours to keep the tracks and third rail clear.[24] The Red Line experienced major service disruptions in the winter of 2014–15 due to frozen-over third rails, leaving unpowered trains stranded between stations with passengers on board.[citation needed]

Rolling stock

The line is standard gauge heavy rail, except for the Mattapan Line, which runs trolleys. Trains consist of mated pairs of electric multiple unit cars powered from a 600V DC third rail. All trains run in six-car sets.

Rolling stock is stabled and maintained at the Cabot Yard near Broadway in South Boston. The connection to this yard is at the junction where the two branches split, near JFK/UMass. Trains are also stabled overnight at Braintree (Caddigan Yard) and Ashmont (Codman Yard), and at the stub tracks west of Alewife.[25] Eliot Yard, on the surface near Harvard, served East Boston Tunnel (now Blue Line) cars for a short time and Red Line cars until it was demolished in the 1970s. (East Boston Tunnel cars accessed the yard through the now-closed Joy Street portal near Bowdoin and a track connection on the Longfellow Bridge).

1912 Cambridge Subway and 1928 Dorchester cars

The Cambridge Subway began service in 1912 with 40 all-steel motor cars built by the Standard Steel Car Company, and 20 cars from the Laconia Car Company. They had a novel design as a result of studies about Boston‘s existing lines, with a then-extraordinary length of 69 feet (21 m) over buffers, and a large standee capacity, while weighing only 85,900 pounds (39,000 kg). They had an all-new door arrangement: three single sliding doors per side evenly distributed along the car‘s length so that the maximum distance to a door was around 9 feet (2.7 m). Upon their debut, the new subway cars were the largest in the world.[26]: 127 A similar configuration was later adopted by the BMT's Standard cars in New York and the Broad Street Subway cars in Philadelphia.

About 20 feet (6.1 m) of the Boston car was separated by a bulkhead for a smoking compartment. In contrast to the elevated lines, passenger flowthrough was not intended, and every door was used as both entrance and exit.[27] Thirty-five cars of similar design were added in 1919 from the Pressed Steel Car Company, followed by 60 more in 1928 from the Bradley Car Company for the Dorchester Extension.[5]

1963 Pullman cars

The 1912-1928 Cambridge-Dorchester fleet remained in service until 1963, when it was replaced all at once by 92 married-pair cars from Pullman-Standard numbered 01400-01491. These carbon-steel cars were originally delivered in a blue, white and gold paint scheme (the state colors of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, who funded their purchase),[28] which they retained into the early 1980s when most were finally repainted into proper Red Line colors for the opening of the Alewife Extension. The 01400s (or 1400s) were the last pre-MBTA transit cars and also the last ones built without air conditioning. All were retired from passenger service by 1994 due to mechanical and electrical equipment not being able to operate with six-car trains. With delivery of the 1800-series, four cars (01469/01470 and 01477/01480) remain as Red Line work equipment and two more are preserved at the Seashore Trolley Museum in Kennebunkport, Maine.[5]

Aluminum-bodied cars

Three series of older aluminum-bodied cars were built: the 1500 and 1600 series by Pullman-Standard 1969–1970 (known as the "No. 1" fleet), and 1700-57 by UTDC in 1988 ("No. 2" fleet). These cars seat 62 to 64 each and approximately 132 cars are in active service as of 2015[update], including some of the oldest cars still in regular revenue service on the MBTA system. All cars are painted white with red trim, with manually operated exterior roll signs. Before their overhauls, the 1500 and 1600 series had a brushed aluminum livery with a thin red stripe and were usually called "Silverbird" cars from their natural metal finish.

All these cars use traditional DC traction motors with electromechanical controls manufactured by Westinghouse and can interoperate. The 1500 and 1700 series cars could operate as singletons, but in practice are always operated as mated pairs. The 1600 series could only operate as married pairs. Originally, the 1500s were double-ended and had two cabs, but were converted to single ended during their midlife overhaul.[29] Headlights are still present on the non-cab ends on the 1500s. The 1700s also have headlights on their non-cab end, but they were built with only one cab.

Stainless steel-bodied cars

The 1800-85 series of stainless steel–bodied cars was built in 1993–94 by Bombardier from components manufactured in Canada and assembled in Barre, Vermont. (This is known as the "No. 3" fleet.) These cars seat 50, and 86 cars are in active service. An automated stop announcement system provides station announcements synchronized with visual announcements in red LED signs ceiling-mounted in each car. These cars are stainless steel with red trim, and use yellow LCD exterior signs. These cars originally had red cloth seats (in contrast to the black leather seats of other cars), but in the early 21st century the cloth seats were replaced with black leather seats. More recently the black leather seats were replaced with vandalism-proof reinforced carpet type seats containing multi-colored patterns, as with the other Red Line stock.

They have modern AC traction motors with solid state controls manufactured by General Electric, can operate only as mated pairs and can partially interoperate with older cars in emergencies or non-revenue equipment moves, but not in revenue service.

Big Red high-capacity cars

In December 2008, the MBTA began running a set of modified 1800 series cars without seats, in order to increase train capacity. The MBTA became the first transit operator in the United States with heavy rail operations to run cars modified for this purpose. These cars have been designated as "Big Red" cars, denoted by large stickers adjacent to the doors. New automated service announcements at stations alert passengers to the arrival of these high-capacity trains.[30] So far, the MBTA has only one pair of modified cars, in a consist that runs only once during the morning rush hour, toward Alewife and once during the evening rush hour toward Braintree, departing Alewife at the top of the evening rush.

Replacement of 1500, 1600, & 1700 series cars

In October 2013, MassDOT announced plans for a $1.3 billion subway car order for the Orange and Red Lines, which would provide 74 new cars to replace the 1500 and 1600 series cars, with an option to increase the number to 132 to replace the 1700 series cars and for more frequent rush hour service.[31]

On October 22, 2014, the Department of Transportation Board awarded Chinese manufacturer CNR a $566.6 million contract to build 132 replacement railcars for the Red Line, as well as additional cars for the Orange Line. CNR will build the Type A cars at a new manufacturing plant in Springfield, Massachusetts at the site of the former New England Westinghouse Company, with initial deliveries of Red Line cars expected in 2019 (Orange Line deliveries will begin a year earlier) and all cars in service by 2023. In conjunction with the new rolling stock, the remainder of the $1.3 billion allocated for the project will pay for testing, signal improvements and expanded maintenance facilities, as well as other related expenses.[32]

The new cars will hold 15 additional passengers, will have four wheelchair parking areas per car, and will be equipped with on-board video surveillance. The cars will have wider doors to allow faster boarding at busy stations, and can allow wheelchair access even if one of a pair of door panels fails to open.[33]

Art and architecture

The MBTA pioneered a "percentage for art" public art program called Arts on the Line during its Northwest Extension of the Red Line in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Arts on the Line was the first program of its kind in the United States and became the model for similar programs for art across the country.

The Kendall/MIT station features an interactive public art installation by Paul Matisse called the Kendall Band, which allows the public to activate three sound-producing machines utilizing levers on the wall of the station. Above the tracks at Alewife hangs a series of red neon tubes called The End of the Red Line, by the Boston artists Alejandro and Moira Sina. Many stations built or renovated in the past three decades now feature public art.[34]

The MBTA maintains an online catalog of the over 90 artworks installed along its six major transit lines. Each downloadable guide is illustrated with full-color photographs, titles, artists, locations, and descriptions of individual artworks.[35]

Newer aboveground stations (particularly Alewife, Braintree, and Quincy Adams, which all have large parking garages) are excellent examples of brutalist architecture.

Advertising

Between South Station and Broadway, as well as Harvard and Central, there have been advertisements in the form of a linear zoetrope. Each frame of the ad is mechanically revealed as the train goes by, to create an animation effect.[36] From time to time, the advertisements are changed or removed altogether. There have been similar advertisements in parts of the New York City Subway, the Washington Metro, Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART), and the Singapore SMRT.[37]

Station listing

| Station | Location | Opened | Transfers and notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alewife Brook Parkway, Cambridge | March 30, 1985[13] | Bus terminal, park and ride garage, Minuteman Bikeway | ||

| Davis Square, Somerville | December 8, 1984[13] | Somerville Community Path | ||

| Porter Square, Cambridge | December 8, 1984[13] | MBTA Commuter Rail, Fitchburg Line | ||

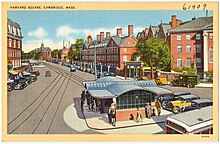

| Harvard Square, Cambridge | September 6, 1983 | Original station opened March 23, 1912 and closed January 30, 1981, replaced by the current station. | ||

| Central Square, Cambridge | March 23, 1912 | |||

| Kendall Square, Cambridge | March 23, 1912 | Originally Kendall until August 6, 1978, named Cambridge Center/MIT between December 2, 1982 and June 25, 1985 | ||

| Cambridge and Charles Streets, Boston | February 27, 1932 | Originally Charles until December 1973 | ||

| Park, Tremont, and Winter Streets, Boston | March 23, 1912 | Green Line Originally Park Street Under | ||

| Summer, Washington, and Winter Streets, Boston | April 4, 1915 | Orange Line and Silver Line Phase I Originally Washington until May 3, 1987 | ||

| Dewey Square, Boston | December 3, 1916 | Silver Line Phase II and MBTA Commuter Rail south side lines Had a transfer to the Atlantic Avenue Elevated | ||

| Broadway and Dorchester Avenue, South Boston | December 15, 1917 | |||

| Andrew Square, South Boston | June 29, 1918 | |||

| North of JFK/UMass, the Red Line surfaces and separates into two branches which operate on separate platforms at JFK/UMass. Just south of the station, the two branches divide as described below. | ||||

| Columbia Road and Morrissey Boulevard, Dorchester | November 5, 1927 | MBTA Commuter Rail: Old Colony Lines and Greenbush Line Originally Columbia until December 1, 1982, Braintree platform opened December 14, 1988 Formerly called Crescent Avenue[38] as an Old Colony Railroad station | ||

| Services to Ashmont and Braintree split | ||||

| Service to Ashmont | ||||

| Savin Hill Avenue and Sydney Street | November 5, 1927 | Formerly an Old Colony Railroad station; tracks for the Braintree branch run next to the station but trains do not stop. | ||

| Charles Street and Dorchester Avenue | November 5, 1927 | Formerly a Shawmut Branch Railroad station | ||

| Dayton Street | September 1, 1928 | |||

| Ashmont Street and Dorchester Avenue | September 1, 1928 | Continuing service to Mattapan via the 10-minute Ashmont-Mattapan High Speed Line (opened December 21, 1929) Formerly a Shawmut Branch Railroad station Cedar Grove station on the Shawmut Branch Railroad is now a station on the Mattapan Line, after which the line merges with the former Dorchester and Milton Branch Railroad right-of-way | ||

| Service to Braintree | ||||

| East Squantum and Hancock Streets, Quincy | September 1, 1971 | |||

| Wollaston | Newport Avenue and Beale Street, Quincy | September 1, 1971 | ||

| Hancock and Washington Streets, Quincy | September 1, 1971 | MBTA Commuter Rail: Old Colony Lines and Greenbush Line, no parking garage active since July 2012. | ||

| Burgin Parkway and Centre Street, Quincy | September 10, 1983 | Park and ride | ||

| Ivory and Union Streets, Braintree | March 22, 1980 | MBTA Commuter Rail: Old Colony Lines Park and ride | ||

References

- ^ "Ridership and Service Statistics" (PDF) (14 ed.). Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ "Wollaston Station Improvements". Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ Cudahy, Brian J. (1972). Change at Park Street Under: The Story of Boston's Subways. Brattleboro, Vermont, US: Stephen Greene Press. ISBN 0-8289-0173-2.

- ^ End of service on Old Colony's Shawmut Branch

- ^ a b c d "The MBTA Vehicle Inventory Page". TransitHistory.org (archived from The New England Transportation Site). Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- ^ Sanborn, George M. (1992). A Chronicle of the Boston Transit System. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority – via MIT.

- ^ "Curiosity Carcards" (PDF). Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority.

- ^ "misc.transport.urban-transit | Google Groups". Groups-beta.google.com. Retrieved 2012-06-10.

- ^ Carr, Robert (29 July 1965). "MBTA Buys Old Colony Line For a South Shore Express". Boston Globe – via Proquest Historical Newspapers.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ "MBTA Plans Downtown Tunnel". Boston Globe. November 20, 1965. p. 4 – via Proquest Historical Newspapers.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ Hanron, Robert (November 7, 1965). "MBTA to Unveil Master Plan Soon For 75-mph Service to Far Points". Boston Globe. p. 48 – via Proquest Historical Newspapers.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ "Frequently Asked Questions on the Fare Restructuring and Increase". Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Belcher, Jonathan (20 July 2011). "Changes to Transit Service in the MBTA district" (PDF). NETransit. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ^ Central Transportation Planning Staff (January 2012). "Improving the Southwest Expressway: A Conceptual Plan" (PDF). Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ^ https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2015/07/28/longfellow-bridge-construction-delayed-two-years/9m7OpQrAIpV6B2IF9mlegL/story.html

- ^ Powers, Martine (February 28, 2013). "Longfellow Bridge repairs, disruption to start in summer". Boston Globe. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ MassDOT. "Longfellow Bridge". Accelerated Bridge Program. Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ Rosen, Andy; Dungca, Nicole (10 December 2015). "Red Line train leaves station without operator". Boston Globe. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- ^ a b Vaccaro, Adam (23 September 2015). "Winter is coming, and the MBTA is getting ready". Boston Globe. Retrieved 4 October 2015.

- ^ "Gov. Baker Announces $83.7 Million MBTA Winter Resiliency Plan" (Press release). Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. 4 June 2015.

- ^ "Winter Resiliency Work Continues on the Red Line: WEEKEND TRAIN SERVICE BETWEEN JFK/UMASS AND QUINCY CENTER SUSPENDED" (Press release). Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. 9 September 2015.

- ^ "MBTA: Next Phase of Red Line Winter Resiliency Improvements Approved". MassDOT Blog (Press release). Massachusetts Department of Transportation. 25 July 2016.

- ^ "What happens on the Red Line stays on the Red Line". Charles River Transportation Management Association. Charles River Transportation Management Association, Inc. Retrieved 2016-02-21.

- ^ Ba Tran, Andrew (23 March 2012). "MBTA Red Line's 100th anniversary". Boston Globe. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ O'Regan, Gerry. "MBTA Red Line". nycsubway.org. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ^ Fischler, Stanley I. (1979). Moving millons : an inside look at mass transit (1st ed.). New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-011272-7.

- ^ Steel Cars for the Cambridge Subway In: Electric Railway Journal, Vol XXXIX, No. 2, p. 58.

- ^ Clarke, Bradley H. (1981). The Boston Rapid Transit Album. Cambridge, MA: Boston Street Railway Association. p. 11.

- ^ http://www.trolleymuseum.org/documents/fundraiser-EastBoston4.pdf

- ^ MBTA strips out the seats from some Red Line trains

- ^ "Governor Patrick Announces Major Transportation Funding Investments". Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. 22 October 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ^ "Chinese Company Hopes MBTA Contract Will Be U.S. Launching Pad". WMUR.com. October 22, 2014. Archived from the original on October 22, 2014. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- ^ "> About the MBTA > News & Events". MBTA. 2014-10-21. Retrieved 2015-02-10.

- ^ "Boston Inspires Public Art" (PDF). Boston Public Library. 2003. pp. 5, 6. Retrieved 2008-09-01.

the MBTA collaborated with the... Cambridge Arts Council... to acquire art for the Red Line Northwest Extension Project. The result was the beginning of a world-class public art program and collection that has grown to include over seventy pieces on six transit lines.

- ^ "Public Art in Transit: Over the Years". mbta.com. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. Retrieved 2014-06-23.

- ^ "The subway tunnel as video billboard". CNET News. Retrieved 2012-06-10.

- ^ "MRT Riders watch tunnel TV". Retrieved 8 November 2009.

- ^ Whiting, E., Map of Dorchester Massachusetts in 1850 - Boston Public Library Map Collection. The maps shows the Crescent Avenue Depot of the Old Colony Railroad Line.

Further reading

- Cheney, Frank. (2002) Boston's Red Line: Bridging the Charles from Alewife to Braintree, Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9780738510477