George Washington's Farewell Address

| |

| Author | George Washington with Alexander Hamilton (1796) and James Madison (1792) |

|---|---|

| Original title | The Address of General Washington To The People of The United States on his declining of the Presidency of the United States |

| Publisher | American Daily Advertiser |

Publication date | September 1796 |

| Text | Washington's Farewell Address at Wikisource |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

American Revolution

1st President of the United States

First term

Second term

Legacy

|

||

George Washington's Farewell Address is a letter written by first President of the United States George Washington to "friends and fellow-citizens".[1] He wrote the letter near the end of his second term of presidency, before retiring to his home at Mount Vernon in Virginia.

It was originally published in David C. Claypoole's American Daily Advertiser on September 19, 1796 under the title "The Address of General Washington To The People of The United States on his declining of the Presidency of the United States", and it was almost immediately reprinted in newspapers across the country and later in pamphlet form.[2] The work was later named the "Farewell Address" as it was Washington's valedictory after 20 years of service to the new nation. It was published about ten weeks before the presidential electors cast their votes in the 1796 presidential election. It is a classic statement of republicanism, warning Americans of the political dangers which they must avoid if they are to remain true to their values.

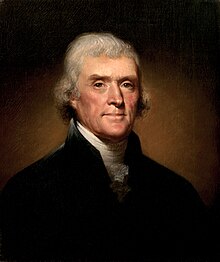

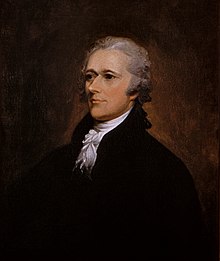

The first draft was originally prepared by James Madison in June 1792, as Washington contemplated retiring at the end of his first term in office.[3] However, he set aside the letter and ran for a second term after the disputes between Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton and Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, which convinced him that growing tensions would rip apart the country without his leadership, including divisions between the newly formed Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties, and the current state of foreign affairs.[4]

As his second term came to a close four years later, Washington prepared a revision of the original letter with the help of Alexander Hamilton to announce his intention to decline a third term in office. He also reflects on the emerging issues of the American political landscape in 1796, expresses his support for the government eight years after the adoption of the Constitution, defends his administration's record, and gives valedictory advice to the American people.[5]

Summary

The thought of the United States without George Washington as its president caused concern among many Americans. Thomas Jefferson disagreed with many of the president's policies and later led the Democratic-Republicans in opposition to many Federalist policies, but he joined his political rival Alexander Hamilton, the leader of the Federalists, in convincing the president to delay his retirement and serve a second term. The two men feared that the nation would be torn apart without his leadership. Washington most likely referred to this when he told the American people that he had wanted to retire before the last election, but was convinced by people "entitled to my confidence" that it was his duty to serve a second term.[4] (All of the ideas presented in Washington's Farewell Address came from Washington; however, Alexander Hamilton wrote most of it.) [6]

Understanding these concerns, Washington sought to convince the American people that his service was no longer necessary by telling them, as he had in his first inaugural address, that he truly believed that he was never qualified to be president. If he accomplished anything during his presidency, he said, it was as a result of their support and efforts to help the country survive and prosper. Despite his confidence that the country would survive without his leadership, Washington used the majority of the letter to offer advice as a "parting friend" on what he believed were the greatest threats to the nation.[4]

Unity and sectionalism

Washington began his warnings to the American people by stressing that their independence, peace at home and abroad, safety, prosperity, and liberty are all dependent upon unity among the states. As a result, he warns them that the union of states created by the Constitution will come under the most frequent and focused attacks by foreign and domestic enemies of the country. He warns the American people to be suspicious of anyone who seeks to abandon the Union, to secede a portion of the country from the rest, or to weaken the bonds that hold the constitutional union together. To promote the strength of the Union, he urges the people to place their identity as Americans above their identities as members of a state, city, or region, and to focus their efforts and affection on the country above all other local interests. He reminds the people that they do not have more than slight differences in religion, manners, habits, and political principles and that their triumph and possession of independence and liberty is a result of working together.[4]

Washington continues to express his support of the Union by giving some examples of how he believes the country, its regions, and its people are already benefiting from the unity that they currently share. He then looks to the future in his belief that the combined effort and resources of its people will protect the country from foreign attack, and allow them to avoid wars between neighboring nations that often happen due to rivalries and competing relations with foreign nations. He argues that the security provided by the Union will also allow the United States to avoid the creation of an overgrown military, which he sees as a great threat to liberty, especially the republican liberty that the United States has created.

Washington goes on to warn the American people to question the ulterior motives of any person or group who argue that the land within the borders of the United States is too large to be ruled as a republic, an argument made by many during the debate on the proposed purchase of the Louisiana Territory, calling on the people to give the experiment of a large republic a chance to work before deciding that it cannot be done. He then offers strong warnings on the dangers of sectionalism, arguing that the true motives of a sectionalist are to create distrust or rivalries between regions and people to gain power and take control of the government. Washington points to two treaties acquired by his administration, the Jay Treaty and Pinckney's Treaty, which established the borders of the United States' western territories between Spanish Mexico and British Canada, and secured the rights of western farmers to ship goods along the Mississippi River to New Orleans. He holds up these treaties as proof that the eastern states along the Atlantic Coast and the federal government are looking out for the welfare of all the American people and can win fair treatment from foreign countries as a united nation.[4]

The Constitution and political factions

Washington goes on to state his support for the new constitutional government, calling it an improvement upon the nation's original attempt in the Articles of Confederation. He reminds the people that it is the right of the people to alter the government to meet their needs, but it should only be done through constitutional amendments. He reinforces this belief by arguing that violent takeovers of the government should be avoided at all costs, and that it is the duty of every member of the republic to follow the constitution and to submit to the laws of the government until it is constitutionally amended by the majority of the American people.[1]

Washington warns the people that political factions may seek to obstruct the execution of the laws created by the government, or to prevent the branches of government from enacting the powers provided them by the constitution. Such factions may claim to be trying to answer popular demands or solve pressing problems, but their true intentions are to take the power from the people and place it in the hands of unjust men.[1]

Washington calls the American people to only change the Constitution through amendments, but he then warns them that groups seeking to overthrow the government may strive to pass constitutional amendments to weaken the government to a point where it is unable to defend itself from political factions, enforce its laws, and protect the people's rights and property. As a result, he urges them to give the government time to realize its full potential, and only amend the constitution after thorough time and thought have proven that it is truly necessary instead of simply making changes based upon opinions and hypotheses of the moment.[1]

Political parties

Washington continues to advance his idea of the dangers of sectionalism and expands his warning to include the dangers of political parties to the country as a whole. These warnings are given in the context of the recent rise of two opposing parties within the government—the Democratic-Republican Party led by Jefferson, and Hamilton's Federalist Party. Washington had striven to remain neutral during a conflict between Britain and France brought about by the French Revolution, while the Democratic-Republicans had made efforts to align with France and the Federalists had made efforts to ally with Great Britain.

Washington recognizes that it is natural for people to organize and operate within groups such as political parties, but he also argues that every government has recognized political parties as an enemy and has sought to repress them because of their tendency to seek more power than other groups and to take revenge on political opponents.[4] He feels that disagreements between political parties weakened the government.

Moreover, he makes the case that "the alternate domination" of one party over another and coinciding efforts to exact revenge upon their opponents have led to horrible atrocities, and "is itself a frightful despotism. But this leads at length to a more formal and permanent despotism." From Washington's perspective and judgment, political parties eventually and "gradually incline the minds of men to seek security... in the absolute power of an individual",[1] leading to despotism. He acknowledges the fact that parties are sometimes beneficial in promoting liberty in monarchies, but argues that political parties must be restrained in a popularly elected government because of their tendency to distract the government from their duties, create unfounded jealousies among groups and regions, raise false alarms among the people, promote riots and insurrection, and provide foreign nations and interests access to the government where they can impose their will upon the country.

Checks and balances and separation of powers

Washington continues his defense of the Constitution by stating that the system of checks and balances and separation of powers within it are important means of preventing a single person or group from seizing control of the country. He advises the American people that, if they believe that it is necessary to modify the powers granted to the government through the Constitution, it should be done through constitutional amendments instead of through force.

Religion, morality, and education

One of the most referenced parts of Washington's letter is his strong support of the importance of religion and morality in promoting private and public happiness and in promoting the political prosperity of the nation.[citation needed] He argues that religious principles promote the protection of property, reputation, and life that are the foundations of justice. He cautions against the belief that the nation's morality can be maintained without religion:

Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports. In vain would that man claim the tribute of patriotism, who should labor to subvert these great pillars of human happiness, these firmest props of the duties of men and citizens. The mere politician, equally with the pious man, ought to respect and to cherish them. A volume could not trace all their connections with private and public felicity. Let it simply be asked: Where is the security for property, for reputation, for life, if the sense of religious obligation desert the oaths which are the instruments of investigation in courts of justice ? And let us with caution indulge the supposition that morality can be maintained without religion. Whatever may be conceded to the influence of refined education on minds of peculiar structure, reason and experience both forbid us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.[1]

Washington refers to religious principle as the foundation of public morality. He also argues that the American government needs to ensure "the general diffusion of knowledge"[5] throughout the United States; the government has been created to enforce the opinion of the people, so the opinion of the people should be informed and knowledgeable.

Credit and government borrowing

Washington provides strong support for a balanced federal budget, arguing that the nation's credit is an important source of strength and security. He urges the American people to preserve the national credit by avoiding war, avoiding unnecessary borrowing, and paying off any national debt accumulated in times of war as quickly as possible in times of peace so that future generations do not have to take on the financial burdens that others have taken on themselves. Despite his warnings to avoid taking on debt, Washington does state his belief that sometimes it is necessary to spend money to prevent dangers or wars that will in the end cost more if not properly prepared for. At these times, he argues, it is necessary for the people to cooperate by paying taxes created to cover these precautionary expenses. He emphasizes how important it is for the government to be careful in choosing the items that will be taxed, but also reminds the American people that, no matter how hard the government tries, there will never be a tax which is not inconvenient, unpleasant, or seemingly an insult to those who must pay it.

Foreign relations and free trade

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2015) |

Washington dedicates a large part of his farewell address to discussing foreign relations and the dangers of permanent alliances between the United States and foreign nations, which he views as foreign entanglements.[7] This issue dominated national politics during the French Revolutionary Wars between France and Britain. Federalists favored Britain and the Jeffersonian Republicans favored France. The Republicans wanted the U.S. to honor the 1778 Treaty of Alliance and to aid France, while the Federalists favored an alliance with Britain. Washington had avoided American involvement in the conflict by issuing the Proclamation of Neutrality, which in turn led to the Neutrality Act of 1794. He tries to further explain his approach to foreign policy and alliances in this portion of the address.

Washington advocates a policy of good faith and justice towards all nations, again making reference to proper behavior based upon religious doctrine and morality. He urges the American people to avoid long-term friendly relations or rivalries with any nation, arguing that attachments with or animosity toward other nations will only cloud the government's judgment in its foreign policy. He argues that longstanding poor relations will only lead to unnecessary wars due to a tendency to blow minor offenses out of proportion when committed by nations viewed as enemies of the United States. He continues this argument by claiming that alliances are likely to draw the United States into wars which have no justification and no benefit to the country beyond simply defending the favored nation. Alliances, he warns, often lead to poor relations with nations who feel that they are not being treated as well as America's allies, and threaten to influence the American government into making decisions based upon the will of their allies instead of the will of the American people.

Washington makes an extended reference to the dangers of foreign nations who will seek to influence the American people and government; nations who may be considered friendly as well as nations considered enemies will equally try to influence the government to do their will. "Real patriots", he warns, who "resist the intrigues" of foreign nations may find themselves "suspected and odious" in the eyes of others, yet he urges the people to stand firm against such influences all the same. He portrays those who attempt to further such foreign interests as becoming the "tools and dupes" of those nations, stealing the applause and praise of their country away from the "real patriots" while actually working to "surrender" American interests to foreign nations. Washington had experience with foreign interference in 1793 when French ambassador Edmond-Charles Genêt organized American demonstrations in support of France, funded soldiers to attack Spanish lands, and commissioned privateers to seize British ships. Genêt's mobilization of supporters to sway American opinion in favor of an alliance with France angered President Washington who ordered him to leave.

Washington goes on to urge the American people to take advantage of their isolated position in the world, and to avoid attachments and entanglements in foreign affairs, especially those of Europe, which he argues have little or nothing to do with the interests of America. He argues that it makes no sense for the American people to become embroiled in European affairs when their isolated position and unity allow them to remain neutral and focus on their own affairs. He argues that the country should avoid permanent alliances with all foreign nations, although temporary alliances during times of extreme danger may be necessary. He states that current treaties should be honored but not extended.

Washington wraps up his foreign policy stance by advocating free trade with all nations, arguing that trade links should be established naturally and the role of the government should be limited to ensuring stable trade, defending the rights of American merchants, and any provisions necessary to ensure the conventional rules of trade.

Address's intentions

Washington uses this portion of the address to explain that he does not expect his advice to make any great impression upon the people or to change the course of American politics, but he does hope that the people will remember his devoted service to his country.

Defense of the Proclamation of Neutrality

Washington then explains his reasoning behind the Proclamation of Neutrality which he made during the French Revolutionary Wars, despite the standing Treaty of Alliance with France. He explains that the United States had a right to remain neutral in the conflict and that the correctness of that decision "has been virtually admitted by all" nations since. Justice and humanity required him to remain neutral during the conflict, he argues, and the neutrality was also necessary to allow the new government a chance to mature and gain enough strength to control its own affairs.

Closing thoughts

Washington closes his letter to the American people by asking them to forgive any failures which may have occurred during his service to the country, assuring them that they were due to his own weaknesses and by no means intentional. The sentences express his excitement about joining his fellow Americans as a private citizen in the free government which they have created together during his 45 years of public service.

Legacy

To this day, Washington's Farewell Address is considered to be one of the most important documents in American history[2] and the foundation of the Federalist Party's political doctrine.

Washington later accepted a commission from President John Adams, despite his stated desire to retire from public service, as the Senior Officer of a Provisional Army formed to defend the nation against a possible invasion by French forces during the Quasi-War.[8] Washington held true to his statements in his farewell address, despite spending months organizing the Officer Corps of the Provisional Army, and declined suggestions that he return to public office in the presidential election of 1800.[8]

Washington's statements on the importance of religion and morality in American politics and his warnings on the dangers of foreign alliances influenced political debates into the twentieth century,[2] and have received special consideration as advice from an American hero.

Alliances with Foreign Nations

Washington's hope that the United States would end permanent alliances with foreign nations was realized in 1800 with the Convention of 1800, the Treaty of Mortefontaine which officially ended the 1778 Treaty of Alliance, in exchange for ending the Quasi-War and establishing most favored nation trade relations with Napoleonic France.[9] In 1823, Washington's foreign policy goals were further realized in the Monroe Doctrine, which promised non-interference in European affairs so long as the nations of Europe did not seek to colonize or interfere with the newly independent Latin American nations of Central and South America. The United States did not enter into any permanent military alliances with foreign nations until the 1949 North Atlantic Treaty[10] which formed NATO.

Reading in Congress

In January 1862 during the American Civil War, thousands of Philadelphia residents signed a petition requesting the Congress to commemorate the 130th anniversary of Washington's birth by reading his Farewell Address "in one or the other of the Houses of Congress".[5] It was first read in the United States House of Representatives in February 1862, and the reading of Washington's address became a tradition in both houses by 1899. The House of Representatives abandoned the practice in 1984,[5] but the Senate continues this tradition to the present. Washington's Birthday is observed by selecting a member of the Senate to read the address aloud on the Senate floor, alternating between political parties each year.[5]

In popular culture

According to political journalist John Avlon, the Farewell Address was "once celebrated as a civic Scripture, more widely reprinted than the Declaration of Independence" but adds that it "is now almost forgotten".[11] He suggested that it had long been "eclipsed in the national memory" until the Broadway musical Hamilton brought it back to popular awareness in the song "One Last Time", where lines are sung by Washington and Hamilton from the end of the Address.[12]

See also

- Federalist Era, the period of American history during which Washington was president

- United States non-interventionism

References

- ^ a b c d e f Washington, George (September 17, 1796). – via Wikisource.

- ^ a b c "Religion and the Founding of the American Republic". Loc.gov. October 27, 2003. Retrieved September 19, 2009.

- ^ "Washington's Farewell Address". University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia: Papers of George Washington. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Elkins, Stanley; McKitrick, Eric (1995). The Age of Federalism: The Early American Republic, 1788-1800. Oxford University Press. pp. 489–499. ISBN 978-0-19-509381-0.

- ^ a b c d e "Washington's Farewell Address, Senate Document No. 106–21, Washington, 2000" (PDF). Retrieved September 19, 2009.

- ^ "George Washington's Farewell Address: Primary Documents of American History (Virtual Programs & Services, Library of Congress)". Web Guides. Retrieved February 26, 2017.

- ^ Bemis, Samuel Flagg (1934). "Washington's Farewell Address: A Foreign Policy of Independence". American Historical Review. 39 (2): 250–268. JSTOR 1838722.

- ^ a b "A Brief Biography of George Washington". Mountvernon.org. Archived from the original on August 23, 2011. Retrieved September 19, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Perspective On The French-American Alliance". Xenophongroup.com. Retrieved September 19, 2009.

- ^ "Online Library: North Atlantic Treaty Organization". Nato.int. Archived from the original on September 13, 2008. Retrieved September 19, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Avlon, John (2017). Washington's Farewell: The Founding Father's Warning to Future Generations. Simon and Schuster. p. 1.

- ^ "What We Can Learn From 'Washington's Farewell'". All Things Considered. National Public Radio. January 8, 2017.

Further reading

- Avlon, John. Washington's Farewell: The Founding Father's Warning to Future Generations (2017) excerpt

- DeConde, Alexander (1957). "Washington's Farewell, the French Alliance, and the Election of 1796". Mississippi Valley Historical Review. 43 (4): 641–658. doi:10.2307/1902277. ISSN 0161-391X.

- Gilbert, Felix (1961). To the Farewell Address: Ideas of Early American Foreign Policy. New York: Harper and Row.

- Hostetler, Michael J. "Washington's farewell address: Distance as bane and blessing". Rhetoric & Public Affairs (2002) 5#3 pp: 393-407. online

- Kaufman, Burton Ira, ed. (1969) Washington's Farewell Address: The View from the 20th Century (Quadrangle Books) essays by scholars

- Malanson, Jeffrey J. (2015) Addressing America: George Washington's Farewell and the Making of National Culture, Politics, and Diplomacy, 1796–1852 (Kent State University Press, 2015). x, 253 pp excerpt

- Pessen, Edward (1987). "George Washington's Farewell Address, the Cold War, and the Timeless National". Journal of the Early Republic. 7 (1): 1–27. doi:10.2307/3123426. ISSN 0275-1275.

- Spalding, Matthew; Garrity, Patrick J. (1996). A Sacred Union of Citizens: George Washington's Farewell Address and the American Character. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-8476-8261-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Spalding, Matthew (1996). "George Washington's Farewell Address". The Wilson Quarterly. 20 (4).

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authormask=ignored (|author-mask=suggested) (help) - Varg, Paul A. (1963). Foreign Policies of the Founding Fathers. Baltimore: Penguin Books.