Moog Modular V

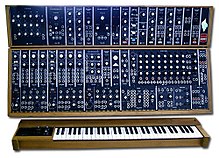

right: Historical Moog synthesizers[1]

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2018) |

Moog synthesizer (pronounced /moʊɡ/ MOHG; often anglicized to /muːɡ/ MOOG, though Robert Moog preferred the former)[2] may refer to any number of analog synthesizers designed by Robert Moog or manufactured by Moog Music, and is commonly used as a generic term for older-generation analog music synthesizers. The Moog company pioneered the commercial manufacture of modular voltage-controlled analog synthesizer systems in the mid 1960s. The technological development that led to the creation of the Moog synthesizer was the invention of the transistor, which enabled researchers like Moog to build electronic music systems that were considerably smaller, cheaper and far more reliable than earlier vacuum tube-based systems.

The Moog synthesizer gained wider attention in the music industry after it was demonstrated at the Monterey International Pop Festival in 1967. The commercial breakthrough of a Moog recording was made by Wendy Carlos in the 1968 record Switched-On Bach, which became one of the highest-selling classical music recordings of its era.[3] The success of Switched-On Bach sparked a slew of other synthesizer records in the late 1960s to mid-1970s.

Later Moog modular systems featured various improvements, such as a scaled-down, simplified, self-contained musical instrument designed for use in live performance.

Early history

The Moog company pioneered the commercial manufacture of modular voltage-controlled analog synthesizer systems. Company founder Robert Arthur Moog had begun manufacturing and selling vacuum-tube theremins in kit form while he was a student in the early 1950s and marketed his first transistorized theremin kits in 1961.[4] Moog became interested in the design and construction of complex electronic music systems in the mid-1960s while completing a Ph.D. in Engineering Physics at Cornell University. The burgeoning interest in his designs enabled him to establish a small company (R. A. Moog Co., which became Moog Music and later, Moog Electronics) to manufacture and market the new devices.

Pioneering electronic music experimenters like Leon Theremin, Louis and Bebe Barron, Christopher R. Morgan, and Raymond Scott had built sound-generating devices and systems of varying complexity, and several large electronic synthesizers (e.g. the RCA Mark II Sound Synthesizer) had been built before the advent of the Moog, but these were essentially unique, custom-built devices or systems. Electronic music studios typically had many oscillators, filters and other devices to generate and manipulate electronic sound. In the case of the electronic score for the 1955 science fiction film Forbidden Planet, the Barrons had to design and build many circuits to produce particular sounds, and each could only perform a limited range of functions.

Early electronic music performance devices like the Theremin were also relatively limited in function. The classic Theremin, for example, produces only a simple sine wave tone, and the antennae that control the pitch and volume respond to small changes in the proximity of the operator's hands to the device, making it difficult to play accurately.

In the period from 1950 to the mid-1960s, studio musicians and composers were also heavily dependent on magnetic tape to realize their works. The limitations of existing electronic music components meant that in many cases each note or tone had to be recorded separately, with changes in pitch often achieved by speeding up or slowing down the tape, and then splicing or overdubbing the result into the master tape. These tape-recorded electronic works could be extremely laborious and time-consuming to create—according to the 1967 Moog 900 Series demonstration record,[5] such recordings could have as many as eight edits per inch of tape. The key technological development that led to the creation of the Moog synthesizer was the invention of the transistor, which enabled researchers like Moog to build electronic music systems that were considerably smaller, cheaper, consumed far less power, and were far more reliable than earlier systems, which depended on the older vacuum tube technology.

Moog began to develop his synthesizer systems after he met educator and composer Herbert Deutsch at a conference in late 1963. Over the next year, with encouragement from Myron Hoffman of the University of Toronto, Moog and Deutsch developed the first modular voltage-controlled subtractive synthesizer. Through Hoffman, Moog was invited to demonstrate these prototype devices at the Audio Engineering Society convention in October 1964,[7] where composer Alwin Nikolais saw them and immediately placed an order.

Moog's innovations were set out in his 1964 paper Voltage-Controlled Electronic Music Modules,[8] presented at the AES conference in October 1964, where he also demonstrated his prototype synthesizer modules. There were two key features in Moog's new system: he analyzed and systematized the production of electronically generated sounds, breaking down the process into a number of basic functional blocks, which could be carried out by standardized modules. He proposed the use of a standardized scale of voltages for the electrical signals that controlled the various functions of these modules—the Moog oscillators and keyboard, for example, used a standard progression of 1 volt per octave for pitch control. This specific definition means that adding or subtracting control voltage simply transposes pitch, a very valuable feature.

At a time when digital circuits were still relatively costly and in an early stage of development, voltage control was a practical design choice. In the Moog topology, each voltage-controllable module has one or more inputs that accept a voltage of typically 10 V or less. The magnitude of this voltage controls one or more key parameters of the module's circuits, such as the frequency of an audio oscillator (or sub-audio "low frequency" oscillator), the attenuation or gain of an amplifier, or the cutoff frequency of a wide-frequency-range filter. Thus, frequency determines pitch, attenuation determines instantaneous loudness (as well as silence between notes), and cutoff frequency determines relative timbre.

Voltage control in analog music synthesizers is similar in principle to how voltage is used in electronic analog computers, in which voltage is a scaled analog of a quantity that is part of the computation. For instance, control voltages can be added or subtracted in a circuit almost identical to an adder in such a computer. Inside a synthesizer VCO, an analog exponential function provides the 1 volt per octave control of an oscillator that basically runs on a volts/kHz basis. Positive voltage polarity raises pitch, and negative lowers it. The result is that, for example, a standard keyboard can have its output scaled to that of a quarter-tone keyboard by changing its output to one-half volt per octave, with no other technical changes.

Using this approach, Moog built a range of signal-generating, signal-modifying and controller modules, each of which could be easily inter-connected to control or modify the functions and outputs of any other. The central component was the voltage-controlled oscillator, which generated the primary sound signal, capable of producing a variety of waveforms including sawtooth, square and sine waves. The output from the VCO could then be modified and shaped by feeding the signal into other modules such as voltage-controlled amplifiers, voltage-controlled filters, envelope generators, and ring modulators. Another customization as part of the Moog Modular Synthesizer is the sequencer, which provided a source of timed step control voltages that were programmed to create repetitive note patterns, without using the keyboard.[9] The inputs and outputs of any module could be cross-linked with patch cords (using tip-sleeve ("mono") ¼-inch plugs) and, together with the module control knobs and switches, could create a nearly infinite variety of sounds and effects.

The final output could be controlled by an organ-style keyboard as the primary user interface, but the notes—individual sounds—could also be triggered and/or modulated by a ribbon controller or by other modules such as white noise generators or low-frequency oscillators. The Moog modular systems were not designed as performance instruments, but were intended as sophisticated, studio-based professional audio systems that could be used as a musical instrument for creating and recording electronic music in the studio.[10]

Moog's first customized modular systems were built during 1965 and demonstrated at a summer workshop at Moog's Trumansburg, New York, factory in August 1965, culminating with an afternoon concert of electronic music and musique concrète on August 28. Although far more compact than previous tube-based systems (e.g. the RCA Mark II) the Moog modular systems were quite large by modern standards, since they predated the introduction of integrated circuit ("microchip") technology; one of the biggest of these, the Moog-based "TONTO" system (built by Malcolm Cecil and used by Stevie Wonder in the 1970s) occupies several cubic meters when fully assembled. These early Moogs were also complex to operate—it sometimes took hours to set up the machine for a new sound—and they were prone to pitch instability because the oscillators tended to drift out of tune as the device heated up.[11] As a result, ownership and use was at first mainly limited to clients such as educational institutions and major recording studios and a handful of adventurous audio professionals.

Ca. 1967, through contacts at the Columbia-Princeton Center, Moog met Wendy Carlos, a recording engineer at New York's studio Gotham Recording and a former student of Vladimir Ussachevsky. Carlos was then building an electronic music system and began ordering Moog modules. Moog credits Carlos with making many suggestions and improvements to his systems. During 1967 Moog introduced its first production model, the 900 series, which was promoted with a free demonstration record composed, realized and produced by Carlos.[4] After assembling a Moog system and a custom-built eight-track recorder in early 1968, Carlos and collaborator Rachel Elkind (secretary to CBS Records president Goddard Lieberson) began recording pieces by Bach that Carlos played entirely on the new Moog. When Moog played one of their pieces at the AES convention in 1968 it received a standing ovation.

The use of flexible cords with plugs at their ends and sockets (jacks) to make temporary connections dates back to cord-type manually operated telephone switchboards (if not even earlier, possibly for telegraph circuits). Cords with plugs at both ends had been used for many decades before the advent of Moog's synthesizers to make temporary connections (patches) in such places as radio and recording studios. These became known as patch cords, and that term was also used for Moog modular systems. As familiarity developed, a given setup of the synthesizer (both cord connections and knob settings) came to be referred to as a patch, and the term has persisted, applying to systems that do not use patch cords.

Late 1960s

French Jean-Jacques Perrey and German-American Gershon Kingsley released albums in the 1960s as Perrey & Kingsley and their second album Kaleidoscopic Vibrations: Electronic Pop Music from Way Out (recorded in America, released 1967) featured the Moog modular synthesizer.

The Moog synthesizer began to gain wider attention in the music industry after it was demonstrated at the Monterey International Pop Festival in June 1967. Electronic music pioneers Paul Beaver and Bernie Krause bought one of Moog's first synthesizers in 1966 and had spent a fruitless year trying to interest Hollywood studios in its use for film soundtracks. In June 1967 they set up a booth at the Monterey festival to demonstrate the Moog, and it attracted the interest of several of the major acts who attended, including the Byrds and Simon & Garfunkel.[14] As the Moog company's sales representatives on the US West Coast,[15] and being among the very few musicians who had been able to master the complex system, Beaver and Krause played a key role in popularizing the Moog III in rock music and in film and television soundtracks.[16][17] After Monterey, the pair enjoyed a steady stream of session work in Los Angeles with their Moog customers and, as the duo Beaver & Krause, a recording contract of their own.[18][19] On the East Coast, Robert Moog's sales representative and business partner was Walter Sear,[20] who also sold large numbers of the instrument in the late 1960s.[21]

The first rock recordings to feature the Moog synthesizer were the songs on Mort Garson's project The Zodiac: Cosmic Sounds, released in May 1967. The Moog subsequently appeared on albums recorded during the Summer of Love era, usually with Beaver or Krause's participation. Among these albums were Strange Days by the Doors (released in September 1967, e.g. the opening track, "Strange Days"),[22] Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn, & Jones, Ltd. by the Monkees (November 1967, e.g. "Daily Nightly", "Star Collector"),[23] The Notorious Byrd Brothers by the Byrds (January 1968, e.g. "Space Odyssey"),[24] and Simon & Garfunkel's Bookends (April 1968, e.g. "Save the Life of My Child"). According to author Mark Brend, the Byrds' October 1967 single "Goin' Back" was the first pop or rock single to feature a Moog part, which was played by Paul Beaver.[25] Brend says that although the Diana Ross & the Supremes single "Reflections" (released in July 1967) is sometimes cited as having Moog synthesizer, the sounds were in fact generated on a test oscillator and treated with effects; Motown, the Supremes' record label, purchased a Moog III, but not until five months after the song's release.[26] It is to note that the first widely viewed television appearance of the Moog III was in 1967 as featured on NBC's "[The Monkees]" television show for the songs "Daily, Nightly" and "Love Is Only Sleeping".

At this early stage the Moog synthesizer was still widely perceived as a novel form of electronic keyboard, not unlike the Mellotron, which had appeared a few years earlier - although the Mellotron (which used taped "samples" of real instruments and voices) had the advantage of being fully polyphonic, a capability Moog synths lacked until the introduction of the Polymoog in 1975. Most early Moog appearances on popular recordings tended to make limited use of the synthesizer, exploiting the new device for its novel sonic qualities. It was generally only used to augment or "color" standard rock arrangements, rather than as an alternative to them—as for example in its use by Simon & Garfunkel on Bookends and by the Beatles' on Abbey Road.[27]

According to the American Physical Society, "The first live performance of a music synthesizer was made by pianist Paul Bley at Lincoln Center in New York City on December 26, 1969. Bley developed a proprietary interface that allowed real-time performance on the music synthesizer." However, according to biographical notes on the Hofstra University website, Herbert Deutsch gave a concert at the New York Town Hall on September 25, 1965 with his New York Improvisation Quartet, which included the first live performance with a Moog synthesizer.[28][29][30] The Moog was also heard on August 28, 1969 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in a performance that included Moog and Deutsch.[31][32]

The Moog synthesizer was also demonstrated in concert at the Art Gallery of Ontario in March 1968, where musician John Mills-Cocknell and his group, Intersystems, performed an interactive art show using a Moog purchased directly from Bob Moog. Another early public performance was a multimedia show in New York by The First Moog Quartet, which used small portable instruments containing 900 series modules. Produced in part by Gershon Kingsley, four New York studio musicians played arrangements while images were projected onto a screen.

Each synthesizer had a custom preset control box which permitted instant configuration changes, akin to a pipe organ's combination action. A lighted pushbutton for each preset made a lamp shine onto photoconductive cells to establish connections. Screwdriver-adjustable trimming pots defined the configurations, of which there were about half a dozen. The synthesizer modules had simple modifications to permit preset control.

Commercial breakthrough

The commercial breakthrough was made by New York-based recording engineer, musician and composer Wendy Carlos who, with producer and collaborator Rachel Elkind, was primarily responsible for introducing the Moog synthesizer to the general public and demonstrating its extraordinary musical possibilities. Carlos worked closely with Moog during 1967-68, suggesting many improvements and refinements to his modules, and during 1967 Carlos composed, realized and produced electronic sounds and music for a demonstration record for the Moog company. Carlos purchased a large Moog modular system in 1968 and then constructed a state-of-the-art eight-track multitrack recorder from superseded studio equipment.[33] Carlos and Elkind then began recording a selection of instrumental compositions by Johann Sebastian Bach, realized entirely on the Moog synthesizer, with each piece painstakingly assembled one part at a time on the multitrack tape.

The resulting album was released by Columbia Masterworks Records in late 1968 under the title Switched-On Bach. It quickly captured the public imagination, becoming one of the highest-selling classical music recordings ever released up to that time and earning Carlos three Grammy awards.[3] The success of Switched-On Bach led to 3 more successful albums of electronically realized Baroque music by Carlos, as well as the acclaimed electronic soundtrack music for the 1971 Stanley Kubrick film adaptation of A Clockwork Orange, which featured original music by Carlos along with several Moog versions of classical pieces by Beethoven and Rossini. Carlos would again employ a Moog synthesizer for the opening of Kubrick's The Shining (1980), which featured a Moog interpretation of the "Dies Irae" (Day of Wrath) section of Hector Berlioz's Symphonie Fantastique.[34]

An important contribution to Moog synthesizer's evolution was made by Keith Emerson, who purchased the second modular system available in the UK. Having difficulties with its assembly and tuning, he collaborated with Dr. Moog himself, thus contributing to the development of even more stable oscillators and numerous new features for live and studio performance. This led the way to full commercial production of many types of synthesizers on the next decade and brought new rival manufacturers to the market.

In July 1969 Dick Hyman's recording of his jazz composition "The Minotaur" became the first Moog-based Billboard Top 40 hit single.[35] Among mainstream rock artists, other early modular Moog users included George Harrison, with his May 1969 Moog album Electronic Sound;[15] Bread, on "London Bridge" from their debut album Bread, released in September 1969; Leon Russell on Stranger in a Strange Land (programmed by Terry Manning), recorded in 1970; and Manning's Home Sweet Home (programmed by Robert Moog himself), which was recorded in 1968 but released in 1970. Following Harrison's example, the Beatles' adoption of Moog synthesizer was reflected prominently in Abbey Road tracks such as "Because", "Here Comes the Sun" and "I Want You (She's So Heavy)".[36]

The success of Switched-On Bach sparked a spate of other synthesizer records in the late '60s–mid '70s. Most of these albums featured cover versions of songs arranged for Moog synthesizer in the most dramatic and flamboyant way possible, covering rock (Switched-On Rock), country and other genres of music. The albums often had "Moog" in their titles (i.e. Country Moog Classics, Martin Denny's Exotic Moog, Gershon Kingsley's Music To Moog By etc.) although many used a variety of other brands of synthesizers and even organs as well. The kitsch appeal of these albums continue to have a small fanbase and the 1990s band The Moog Cookbook is a tribute to this style of music. Indeed, considering it was the first practical and widely used analog synthesizer, many people came to use "moog" to refer to music synthesizers in general (an example of genericization).

1970s

The popularity and cultural impact of the synthesizer greatly expanded following Moog's development of the monophonic "Minimoog" synthesizer, introduced in 1970, which was designed for live performance. Although nowhere near as powerful as its modular siblings, the Minimoog was highly flexible, relatively easy to use, and offered enormous advantages for touring bands in live performance – the briefcase-sized unit was small, light and portable (it could easily be carried by one person), it could plug into any standard instrument amplifier, it was relatively rugged and reliable, and the programming was entirely controlled by hard-wired knobs and switches, rather than the maze of patch cords used on Moog's modular synths. Above all, the Minimoog was comparatively very affordable – at an initial retail price of US$1500, it was less than half the cost of Moog's cheapest professional modular system – according to the company's 1974 price list, a Moog System 15 was almost $4000, the System 35 was over $5000, and the largest, the System 55 (pictured above) cost nearly $9000, while the System 55A, plus optional sequencer module, cost well over $10,000.[37]

Avant garde jazz musician Sun Ra was loaned a Minimoog prototype B in 1969 by Robert Moog after Sun Ra was shown a demonstration of the modular Moog. This loan acted as a field test of sorts for how well the Minimoog would stand up to the stress of on the road touring. Sun Ra's first recording with a Minimoog was in November 1969 and subsequently often used the Moog as his instrument of choice to achieve his unique sound including later acquiring two Minimoogs to get duophonic tones.[38] From 1971, the Minimoog was rapidly taken up by a number of musicians, notably Rick Wakeman of progressive rock group Yes (who regularly used two Minimoogs on stage), and Jan Hammer of the Mahavishnu Orchestra. The Minimoog proved versatile enough to allow Hammer to solo with equal musicality/facility to that of his colleagues John McLaughlin on guitar and Jerry Goodman on violin. Likewise, the Minimoog, as played by the classically trained Wakeman, provided Yes with a second solo instrument that equalled and complemented the sonic colour, range, power and musical dexterity of guitarist Steve Howe. Indeed, Wakeman's recruitment to Yes in late 1971 came about in part because he already owned a Minimoog, and because the band's original keyboard player Tony Kaye (who preferred the more traditional sounds of the Hammond organ) was sacked partly because he was reluctant to use newer electronic keyboards like the Mellotron and the Moog.

One of the most important and successful uses of the Moog in popular music in the early to mid-1970s was the extended collaboration between Stevie Wonder and electronic musicians Malcolm Cecil and Robert Margouleff on the series of albums Wonder released during this period. These recordings made extensive use of the duo's large synthesiser system, which they dubbed TONTO (an acronym for "The Original New Timbral Orchestra"), reputedly the world's first and largest multitimbral polyphonic analog synthesizer. Designed and constructed by Cecil, it was based on Moog Series III components, together with additional modules made by other manufacturers including ARP.

The duo's 1971 album Zero Time – released under the pseudonym "Tonto's Expanding Head Band" – gained critical acclaim and attracted the attention of many musicians including Wonder. He first worked with Cecil, Margouleff and TONTO on his 1972 album Music of My Mind and the collaboration continued and expanded over his subsequent albums, Talking Book (1972), which won several Grammy awards, Innervisions (1973), which won the 'Album of the Year' Grammy, Fulfillingness' First Finale (1974) . Another early use of the synthesiser in the popular music realm was in Australia, where keyboard player Michael Carlos of the pioneering progressive rock group Tully purchased what is thought to have been the first modular Moog system imported into Australia, and used it both on the group's recordings and in live performance.

A custom Moog Modular System was also featured prominently on Emerson, Lake & Palmer's song "Lucky Man" (1970), in Keith Emerson's Moog solo at the end. Klaus Schulze used the Big Moog for the first time on another famous album, Moondawn, after he had obtained this synthesizer from Florian Fricke of Popol Vuh. Another famous use of the Moog was in Tangerine Dream's electronic landmark album Phaedra in 1974, which was a major hit in the UK—it reached #15 on the British album charts and playing a significant role in establishing the fledgling independent label Virgin Records.

Perhaps the most commercially successful pop-industry recording primarily featuring the Moog was Hot Butter's cover version of "Popcorn", an instrumental composed and first recorded by Kingsley in 1969 for Music to Moog By. Released as a single in 1972, Hot Butter's version was number 1 in Australia and in several European countries, and peaked at number 5 in the UK and number 9 in the US.

German-based producer-composer Giorgio Moroder and British producer/writer Pete Bellotte incorporated the Moog synthesizer in the 1977 Donna Summer hit "I Feel Love". The use of the synthesizer created the pulsing synched feel that is characteristic of dance music and became a benchmark for the Moog sound in disco. The Moog bassline in this song complemented the other Moog tracks, the only non-Moog track being the bass drum.

In 1979 the Moog synthesiser returned to the mainstream pop market through British singer-songwriter Gary Numan. Numan used Minimoogs and Polymoogs extensively on his albums Tubeway Army, Replicas and The Pleasure Principle. He continued to use Moogs through much of his career.

Product development

Later Moog modular systems featured improvements to the electronics design, and in the early 1970s Moog introduced new models featuring scaled-down, simplified designs that made them much more stable and well suited to real-time musical performance. In 1970, Moog (R. A. Moog Inc. at that time) began production of the Minimoog Model D,[4] a small, monophonic three-oscillator keyboard synthesizer that—alongside the British-made EMS VCS 3 — was one of the first widely available, portable and relatively affordable synthesizers. Unlike the early modular systems, the Minimoog was specifically created as a self-contained musical instrument designed for use in live performance by keyboard players. Although its sonic capabilities were drastically reduced from the large modular systems, the Minimoog combined a user-friendly physical design, pitch stability, portability and the ability to create a wide range of sounds and effects.

An important Minimoog innovation was a pair of wheel controllers that the musician could use to bend pitch and control modulation effects in real time. The two wheels are mounted to the left of the keyboard, next to the lowest key. The function of the Pitch wheel was assigned solely to control oscillator pitch (either sharp or flat from a default, detented, non spring-loaded center position), whereas its neighboring Mod (Modulation) wheel was assignable to control a mixable amount of oscillator 3 and/or Noise routed to the three oscillators and/or the VCF cutoff frequency. In particular, the intuitive function and feel of the Pitch wheel allowed Minimoog users to create similar expressive pitch-bending effects that musicians such as guitarists achieve by physically 'bending' strings and using "whammy" bars.

Though various synthesizer manufacturers have used many other types of left hand controllers over the years—including levers, joysticks, ribbon controllers, and buttons—the pitch and mod wheels introduced on the Minimoog have become de facto standard left-hand controllers, and have since been used by almost every major synthesizer manufacturer, including Korg, Yamaha, Kawai, and (now defunct) Sequential Circuits on their ground-breaking Prophet-5 programmable polyphonic synthesizer (1977). A notable exception is the Japanese manufacturer Roland, who have typically never included Pitch and Modulation wheels as the primary controller on any synthesizer, instead including alternative controllers of their own design. However, they included the wheels as secondary controllers on their JD-XA synthesizer and as the primary controller on their JD-Xi synthesizer.

The Minimoog was the first product to solidify the synthesizer's popular image as a "keyboard" instrument and the most monophonic synthesizer sold approximately 13,180 units between 1970 and 1981,[4] and it was quickly taken up by leading rock and electronic music groups such as the Mahavishnu Orchestra, Yes, Emerson, Lake & Palmer, Tangerine Dream and Gary Numan. Although the popularity of analog synthesis faded in the 1980s with the advent of affordable digital synthesizers and sampling keyboards, the Minimoog remained a sought-after instrument for producers and recording artists, and it continued to be used extensively on electronic, techno, dance and disco recordings into the 1980s due to its distinctive tonal qualities, particularly that of its patented Moog "ladder" filter.

The rarest Moog production model was the little Minitmoog (1975–76), a direct descendant of the rather obscure Moog Satellite preset synthesizer. It is rumored that only a few hundred Minitmoogs were made, although firm numbers are unavailable. While it lacked programmability and memory storage, the Minitmoog did offer some forward features, such as keyboard aftertouch and a sync-sweep feature, thanks to its dual voltage controlled oscillators.

The Taurus bass pedal synthesizer was released in 1975. Its 13-note pedalboard was similar in design to small spinet organ pedals and triggered bold, penetrating synthesized bass sounds. The Taurus was known for an especially "fat" bass timbre and was used by Genesis, Rush, Electric Light Orchestra, Yes, Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, Parliament-Funkadelic, Paul Davis, and many others. Production of the original was discontinued in 1981, when it was replaced by the Taurus II. In November 2009, Moog Music introduced the limited production Moog Taurus 3 pedal synthesizer, which, the company reports, exactly duplicates the original Taurus I timbre and presets, while adding modern features such as velocity sensitivity, greatly expanded memory for user presets, a backlit LC display, and MIDI and USB interfacing. Still, the original Taurus I units are highly sought after and typically command a high resale value on the used market.

Moog Music was the first company to commercially release a keytar, the Moog Liberation. The last Moog synthesizer released by the original Moog Music, the programmable polyphonic Memorymoog (and subsequent Memorymoog Plus), was manufactured from 1983 to 1985, just before the company declared bankruptcy in 1986.

By the mid-1990s, analog synthesizers were again highly sought after and prized for their classic sound. In 2001, Robert Moog's company Big Briar was able to acquire the rights to the Moog name and officially became Moog Music. Moog Music has been producing the Minimoog Voyager modeled after the original Minimoog since 2002. As of 2006, more than 15 companies are making Moog-style synthesizer modules.

In March 2006, Moog Music unveiled the Little Phatty Analog Synthesizer, boasting "hand-built quality and that unmatched Moog sound, at a price every musician can afford". The first limited edition run of 1200 were a Bob Moog Tribute Edition with a Performer edition announced subsequently. In 2011, a number of Moog products can still be purchased, such as Moogerfoogers, Taurus 3 bass pedals and Minimoog Voyagers.

Since 2014, additional models to the Moog line have include the Moog Sub Phatty and a 37-key knob-per-function variant, titled the Moog Sub 37. As production and development has progressed with the Sub Phatty, Moog has stopped production on the Little Phatty line, including an announcement in late 2014 to discontinue its rackmount model, the Slim Phatty.

At the 2015 NAMM Show, Moog announced plans to reintroduce its original modular synthesizer systems, using original schematics and designs from 1970s models, offering a new line of Moog System 55, Moog System 35, and Moog Model 15 modulars.

In summer 2018 the Moog One polyphonic synth was introduced. There is a 8 and a 16 voice version available with the very same outer design.

List of models

- Moog modular synthesizer (1963–80, 2015–present)

- Minimoog (1970–81, 2016–present)[4]

- Moog Satellite (1974–79)

- Moog Sonic Six (1974–79)

- Minitmoog (1975–76)

- Micromoog (1975–79)

- Polymoog (1975–80)

- Moog Taurus (bass pedals) (1976–83)

- Multimoog (1978–81)

- Moog Prodigy (1979–84)

- Moog Liberation (1980)

- Moog Opus 3 (1980)

- Moog Concertmate MG-1 (1981)

- Moog Rogue (1981)

- Moog Source (1981)

- Memorymoog (1982–85)

- Moogerfooger (1998–present)

- Minimoog Voyager (2002–15)

- Moog Little Phatty (2006–13)

- Slim Phatty (2010–14)

- Taurus 3 bass pedal (2011)

- Minitaur (2012)

- Sub Phatty (2013)

- Sub 37 (2014)

- Moog Werkstatt-Ø1 (2014, kit)

- Emerson Moog Modular (2014)[40]

- Mother-32 (2015–present)[41]

- Subsequent 37 CV - limited run of 2,000 units (2017)

- Subsequent 37 (2017)

- Moog DFAM (Drummer From Another Mother) - first as a limited kit for the 2017 Moogfest (2017 kit, 2018-present)

- Moog Subharmonicon - limited kit made for 2018 Moogfest (2018 kit)

- Moog Grandmother (2018-present)

- Moog One (2018-present)

- Sirin: Analog Messenger of Joy (2019-present)[42]

Legacy

On May 23, 2012, a replica of the Moog synthesizer was featured as a Google Doodle honoring Dr. Robert Moog's 78th birthday.[43]

The Boise, Idaho, band The Dirty Moogs is named after the instrument, cast-off examples of which were typically found in decrepit condition.[44]

See also

- Animoog, Moog's tablet and smartphone synthesizer

- List of Moog synthesizer players

References

- ^ a b

"Collection checklist" (PDF). Calgary, Canada: National Music Centre. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-06-30. Retrieved 2016-03-12.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Wells, John C. (2009). "Moog". Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. London: Pearson Longman.

- ^ a b Holmes 2002, p. 178

- ^ a b c d e f "MOOG ARCHIVES". www.moogarchives.com. Archived from the original on 3 November 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Moog Archives". moogarchives.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^

"This Week in Synths: The Stearns Collection Moog, Mike Oldfield's OB-Xa, MOOG IIIp". Create Digital Music. 2007-03-23. Archived from the original on 2008-07-04.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

"Stearns Collection". School of Music, Theatre & Dance, University of Michigan. Archived from the original on 2010-03-28.{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

Moog synthesizer, Stearns 2035 Archived 2010-06-21 at the Wayback Machine is known as 1st commercial Moog synthesizer commissioned by the Alwin Nikolais Dance Theater of New York in October 1964. Now it resides as part of the Stearns Collection at the University of Michigan - ^ Holmes 2002, pp. 164–65

- ^ R. A. Moog, Journal of the Audio Engineering Society, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 200–206, July 1965.

- ^ Holmes, Thom (2008).Electronic and Experimental Music: Technology, Music, and Culture, pp 214. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-95782-3.

- ^ Selinger, Evan (ed.) (2006). Postphenomenology: A Critical Companion to Ihde, pp. 58–59. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-6787-2.

- ^ The original modular VCOs were based on a very-simple (and very inexpensive) unijunction transistor sawtooth oscillator. The exponential computing circuit was temperature-compensated, but also of simple, open construction that made it very difficult (author's personal experience) to trim internally. Beginning with oscillators for the ARP modular analog synthesizers, far more attention was paid to oscillator stability (and frequency range; the Moog was rather limited). This is not meant to denigrate Dr. Moog; he did what made sense in the context of the time. Nevertheless, the landmark record "Switched-On Bach" (W. Carlos) solidly established analog synthesizers as keyboard-controlled instruments.

- ^

"Max Brand Synthesizer". Zaubethafte Klangmaschinen. Institut of Media Archaeologie. Archived from the original on 2011-07-06.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^

"From the Archives: Moogtonium Discovered". Bob Moog Foundation. January 2009. Archived from the original on 2012-03-19.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Brend 2012, p. 88.

- ^ a b Holmes 2012, p. 446.

- ^ Brend 2012, pp. 151, 166–68.

- ^ Pinch & Trocco 2002, p. 315.

- ^ Brend 2012, pp. 166–67.

- ^ Pinch & Trocco 2002, pp. 117, 123.

- ^ Pinch & Trocco 2002, p. 88.

- ^ Braun 2002, p. 75.

- ^ "CLASSIC TRACKS: The Doors 'Strange Days' |". Archived from the original on 2013-09-09. Retrieved 2013-08-07.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Holmes 2002, p. 167

- ^ Holmes 2012, p. 248.

- ^ Brend 2012, p. 90.

- ^ Brend 2012, pp. 164–65.

- ^ Braun 2002, pp. 75–76.

- ^ hofstra.edu Archived 2008-09-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ moogarchives.com Archived 2009-04-22 at the Wayback Machine

"This Moog synthesizer... was kept by the inventor and his colleague, Herbert Deutsch. It was used in live public performance for the first time in a concert at Town Hall in New York City on September 25, 1965."

The instrument was donated to The Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan. - ^ Deutsch, Herbert A. (Fall 1981). "The Moog's First Decade, 1965–1975". NAHO.

Excerpt online: "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-02-17. Retrieved 2009-08-30.{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ moogarchives.com, Interview with Herbert A. Deutsch Archived 2009-08-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Moog archives, quoting New York Post 29 Aug 1969 Archived 2009-01-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Carlos, Wendy (1999), Switched-On Bach Boxed Set, New Notes

- ^ "Kubrick's The Shining - The Opening". idyllopuspress.com. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Joel Whitburn, Billboard Book of Top 40 Hits. ('The Minotaur' climbed to number 38)

- ^ Holmes 2012, pp. 446–47.

- ^ "Vintagesynth.com - Moog 1974 price list" (PDF). vintagesynth.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Sun Ra & the Minimoog". moogfoundation.org. 2013-11-06. Archived from the original on 3 March 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^

"The Moog Modular returns! - System 55, 35 and Model 15 manufactured for first time in decades". Sound On Sound. 2015-01-19. Archived from the original (news) on 2015-06-25.

Today, Moog Music Inc. announce their plans to commence the limited-run manufacturing of three of their most sought after 5U large format modular synthesizers: The System 55, the System 35 and the Model 15. ...

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^

Reid, Gordon. "The Rebirth Of Keith Emerson's Moog Modular - Second Coming". Sound on Sound (July 2014). Archived from the original on 2015-03-25.

The stuff of synthesizer legend, Keith Emerson's megalithic modular system hasn't just been restored ? it's also been completely recreated.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "INTRODUCING MOTHER-32 - Moog Music Inc". www.moogmusic.com. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Sirin". www.mooghouseofelectronicus.com. Retrieved 24 Jan 2019.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Geeta Dayal (23 May 2012). "Geekiest Uses (So Far) of Google's Moog Synthesizer Doodle". Wired. Archived from the original on 25 May 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Deeds, Michael (2017-04-16). "And Now For Something Completely the Same". The Idaho Statesman. Retrieved 2018-01-01.

Sources

- Braun, Hans-Joachim (ed.) (2002) [2000]. Music and Technology in the Twentieth Century. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6885-6.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brend, Mark (2012). The Sound of Tomorrow: How Electronic Music Was Smuggled into the Mainstream. London: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-0-8264-2452-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Holmes, Thom (2002). Electronic and Experimental Music: Pioneers in Technology and Composition (2nd ed.). New York and London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-93643-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Holmes, Thom (2012). Electronic and Experimental Music: Technology, Music, and Culture (4th edn). New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-89636-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pinch, Trevor; Trocco, Frank (2002). Analog Days: The Invention and Impact of the Moog Synthesizer. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01617-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)