Common house gecko

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (October 2012) |

| Common house gecko | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Family: | Gekkonidae |

| Genus: | Hemidactylus |

| Species: | H. frenatus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Hemidactylus frenatus | |

| |

The common house gecko (Hemidactylus frenatus) (not to be confused with the Mediterranean species Hemidactylus turcicus known as Mediterranean house gecko), is a gecko native of Southeast Asia. It is also known as the Pacific house gecko, the Asian house gecko, house lizard, or moon lizard.

Most geckos are nocturnal, hiding during the day and foraging for insects at night. They can be seen climbing walls of houses and other buildings in search of insects attracted to porch lights and is immediately recognisable by its characteristic chirp.

They grow to a length of between 75–150 mm (3–6 in), and live for about 5 years. These small geckos are non-venomous and not harmful to humans. Medium to large geckos may bite if distressed; however, their bite is gentle and will not pierce skin. A tropical gecko, Hemidactylus frenatus thrives in warm, humid areas where it can crawl around on rotting wood in search of the insects it eats, as well as within urban landscapes. The animal is very adaptable and may prey on insects and spiders, displacing other gecko species which are less robust or behaviourally aggressive.

Habitat and Diet

The common house gecko is by no means a misnomer, displaying a clear preference for urban environments. The synanthropic gecko displays a tendency to hunt for insects in close proximity to urban lights.[3] They have been found in bushland, but the current evidence seems to suggest they have a preference for urban environments, with their distribution being mostly defined by areas within or in close proximity to city bounds.[4]

The common house gecko appears to prefer areas in the light which are proximal to cracks, or places to escape. Geckos without an immediate opportunity to escape potential danger display behavioural modifications to compensate for this fact, emerging later in the night and retreating earlier in the morning[5]. Without access to the urban landscape, they appear to prefer habitat which is composed of comparatively dense forest or eucalypt woodland which is proximal to closed forest[6].

The selection of primarily urban habitats makes available the preferred foods of the common house gecko. The bulk of the diet of the gecko is made up of invertebrates, primarily hunted around urban structures[3]. Primary invertebrate food sources include cockroaches, termites, some bee and wasps, butterflies, moths, flies, spiders, and several beetle groupings[3]. There is limited evidence that cannibalism can occur in laboratory conditions, but this is yet to be observed in the wild[7] .

Distribution

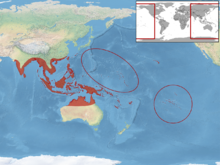

The common house gecko is prolific through the tropics and subtropics. It is capable of existing in an ecologically analogous place with other Hemidactylus species[8].Despite being native throughout South East Asia, recent introductions, both deliberate and accidental have seen them recorded in the Deep South of the United States, large parts of tropical and sub-tropical Australia, and many other countries in South and Central America, Africa, South Asia, and the Middle East. Their capacity to withstand a wide range of latitudes is also partially facilitated by their capacity to enter a state of brumation during colder months. The prospect of increased climate change interacts synergistically with increased urbanisation, greatly increasing the prospective distribution of the common house gecko. [8]Due to concerns over its potential capacity as an invasive species, there are efforts to limit their introduction and presence in locations where they could be a risk to native gecko species.

As an Invasive Species

There is evidence to suggest that the presence of Hemidactylus frenatus has negatively impacted native gecko populations throughout tropical Asia, Central America and the Pacific[8].

Some species which have been displaced include:

- Lepidodactylus lugubris[9][10][11][12]

- Hemidactylus Garnotti[9][10][11][12]

- The Nactus Genus on the Mascarene Islands (3 are now considered to be extinct)[13]

As an introduced species, they prose a threat through the potential introduction of new parasites and diseases but have potential negative impacts which extend beyond this[14]. The primary cause for concern appears to exist around their exclusionary behaviour and out-competition of other gecko species[7][10]. Mechanistically, three explanations have been derived to justify the capacity of H. frenatus to outcompete other Gecko species:

1. Possessing a larger body size. They fail to displace larger native species, such as the Robust Velvet Gecko[15]

2. Male H. frenatus displaying higher levels of aggression than females of other gecko species (particularly parthenogenic species with asexual females).

3. Sexual females displaying an increased capacity to compete in comparison to Asexual females.[10]

These differences provide H. frenatus a competitive edge in the limited urban areas they preferentially inhabit, particularly those with high degrees of habitat fragmentation[9]. To compound this, they also are capable of operating on higher densities, which leads to an increase in Gekkonidae sightings and biomass in an area, even after reducing native species density[9]. The common house gecko also displays a higher tolerance to high light levels, which may allow for an increased risk-reward pay off in hunting endeavours. There is also some limited evidence for cannibalism, hunting on other small Gecko species, particularly juveniles[7]. Most of this evidence is in laboratory conditions, with several studies failing to find evidence of cannibalism in the wild for this species[9] [16].

More aggressive and territorial males will display larger heads, with a more pronounced head shape. This increase in size is disproportionate and incurs a poorer performance in sprint time. This suggests selective pressure prioritises the competitive capacity of the male, rather than their capacity to escape quickly. On the contrary, increases in female head size are met with a proportionate increase in hind limb length and no decrease in speed. This proportionate increase suggests that the demand on mobility from females is of greater pressure on selection. Males, instead, are selected for the capacity to compete[17] .

The success of the common house gecko can also be explained through more subtle elements of competition, such as behavioural dominance. An example of this is how they trigger an avoidance response in the Mourning Gecko[10]. As well as triggering this response, they tolerate the presence of their own and other gecko species well[9] [13] allowing them to out-reproduce Gecko species which have pairings as a main social structure[18]

These factors place the common house gecko as being capable of displacing other gecko species, particularly asexual and smaller species [9]. However, there is also evidence to suggest that they can co-exist with other gecko populations, especially those who are larger, sexual and aggressive.[8]

Physiology

The common house gecko is ectothermic (“cold blooded”) and displays a variety of means of thermoregulating through behaviour. Its physiology has ramifications for its distribution and nature of interaction with native species, as well as reproductive success as an introduced species.

Metabolically, the demand of the common house gecko is not significantly variable from other lizard species of a similar size, with Oxygen consumption appearing congruent with trends observed in other tropical, subtropical and temperate species of gecko. Thermal independence exists between 26-35 degrees, with some capacity to self regulate temperature. This means that where the environmental temperature is 26-35 degrees, the common house gecko can modify body temperature through behavioural adaptations. Breathing rates of the Gecko are temperature dependent above this maximal heat, but independent as it grows colder[19]. There are behavioural mechanisms of thermoregulation present, such as the selection of sunlight[20] and substrates on which they sit.

The common house gecko can be best defined as quinodiurnal. This means they thermoregulate during the daytime and forage at night[21]. An active form of this thermoregulation includes the presence of the Gecko in lighter environments, proximal to cracks in the substrate. As such, there is a close relationship between activity levels and correlated air temperature[5] . Timing of the circadian rhythm of the common house gecko is further impacted by light levels.This rhythm tends to involve the highest population presence around midnight, with highest activity levels just after sunset[22], with a gradual reduction until dawn. Daily cycle differences from place to place can generally be explained by environmental factors such as human interaction, and structural features[5]. A peak in hunting activity after dark places them in an ideal spot to take advantage of invertebrate congregation around artificial lighting in the urban environment.

Due to this level of dependence on the environment, drops in temperature may act as a leading indicator for reduced Gecko sightings in the medium term. Acute weather events such as rain or wind will result in acute decreases in Gecko sightings within that environment. It is unsure what impact these phenomena may have on the long term on distribution and the capacity of the common house gecko to compete with other gecko species.

There is some weak evidence to suggest a trend towards higher temperature for females, which has an evolutionary advantage of increasing the speed of egg development. However, there fails to any statistically significant data to support this[21].

Due to them being a species which is adapted for tropical or subtropical environments, there appear to be few physiological adaptations designed to prevent water loss. This may limit their capacity to thrive in arid or semi-arid environments.[19].

Reproductive Biology

H. frenatus has a similar gonad structure to the remainder of the gekkonid family. It is possible to differentiate the sex of larger common house geckos, with individuals which are larger than 40mm typically displaying differentiated gonads. Differentiated gonads are most clearly seen with a swelling at the entrance to the cloaca caused by the copulatory organs in males. Females lay 2 a maximum of 2 hard-shelled eggs at any single time, with each descending from a single oviduct. Up to 4 eggs can exist within the ovaries in differing stages of development. This shortens the potential turn around between egg laying events in gravid females[23]. Females produce a single egg per ovary per cycle. This means they are considered monoautochronic ovulatory [24].

Within the testes, mature sperm are found by the Geckos year-round and are able to be stored within the oviduct of the female. Sperm can be stored for a period of time as long as 36 weeks. This provides a significantly increased chance of colonisation of new habitats, requiring smaller populations to be transplanted for a chance of success. However, longer storage time of sperm within the female is associated with negative survival outcomes and hatching, possibly due to sperm age. Sperm is specifically stored between the uterine and infundibular components of the oviduct. The capacity to store sperm enables a degree of asynchrony between ovulation, copulation and laying of eggs[24].The capacity to store sperm is useful in island colonisation events, providing females which may be isolated the capacity to reproduce even if they have been separated from a male for some time[25]. In laboratories, one mating event may produce as many as 7 viable egg clutches. This eliminates the need for parthenogenesis and allows the young to include both male and female offspring, with one mating event leading to multiple clutches of eggs being laid. This reduced need to asexual reproduction increases the fitness of young through hybrid vigour and increased diversity[24]. As well as this, sexually reproducing geckos are reported to be more robust and have higher survival rates than those which reproduce asexually.[8]

There is a positive correlation between size and viability of eggs, with larger Geckos having eggs which were more likely to survive. There is also a correlation between warmer year-round temperatures and consistent food supply with reproductive seasonality, with Geckos with constant food and temperatures being less likely to develop fat deposits on their stomach, and more likely to be constantly reproductive[23]

Communication

The common house gecko possesses a series of distinct calls and communication cools. Marcellini contends that they have 3 functional and distinct calls[26].

Churr.

The Churr call is used infrequently, and only during aggressive encounters between males. It is considered intimidatory and used when males are within 1m of each other after the commencement of vigourous posturing. These postures involve the mouth being kept open at the other Gecko and have not been recorded between juveniles and females.

Single Chirp

The Singe Chirp call is associated with levels of distress within the animal. It has been detected within males more frequently but has been seen in adults, subadults and Juveniles. However, it has yet to be recorded in the presence of Gecko under the size of 35mm. In laboratory conditions, the sound can be provoked when handled roughly by a human or another animal. It can also be created by placing a large number of Gecko in a small environment together. It will be generally observed concurrently with a tail bite between two competing Gecko.

Gack Gack Gack (Multiple Chirp)

The multiple chirp is an agonistic and territorial defence. It is the most common of the sounds and has a broad range of intensities it can occupy. This call can be triggered by a recording close by and is typically given more often by an aggressive male, and less often by a female[26]. This call will produce a weak response from females involving them moving[27]. Geckos smaller than 45 mm will rarely utter it. It is commonly done at the conclusion of activities such as mating and eating, and less commonly during courtship encounters and between females. It is most frequently observed between two aggressive males. As such, males will react more clearly to it. There is a general positive correlation between the number of Gecko in an environment and the number of these calls, but other factors which include its intensity and presence include human presence and sunlight[26].

Genetics

Two distinct karyotypes of the common house gecko appear to exist, one with 40 Chromosomes, and one with 46 Chromosomes[28][29] . This could be explained through an intraspecific variation of karyotype, or the possibility of two distinct species being misidentified. Morphological analysis seems particularly congruent with the suggestion that they indeed are different species[29][30]. Taxonomic revision may be required as a greater understanding of phylogenetic trees and population structures is developed.

Etymology

Like many geckos, this species can lose its tail when alarmed. Its call or chirp rather resembles the sound "gecko, gecko". However, this is an interpretation, and the sound may also be described as "tchak tchak tchak" (often sounded three times in sequence). In Asia/Southeast Asia, notably Indonesia, Thailand, Singapore, and Malaysia, geckos have local names onomatopoetically derived from the sounds they make: Hemidactylus frenatus is called "chee chak" or "chi chak" (pr- chee chuck), said quickly. Also commonly spelled as "cicak" in Malay dictionaries. In the Philippines they are called "butiki" in Tagalog, "tiki" in Visayan, "alutiit" in Ilocano, and in Thailand "jing-jok" (Thai: จิ้งจก[31]). In Myanmar, they are called "အိမ်မြှောင် - ain-mjong" ( "အိမ် - ain" means "house" and "မြှောင် - mjong" means "stick to"). In some parts of India and in Pakistan they are called "chhipkali" (Urdu:چھپکلی, Hindi: छिपकली), from chhipkana, to stick. In Nepal they are called "vhitti" (Nepali: भित्ती) or "mausuli" (Nepali: माउसुली). In other parts of India they are called "kirli" (Punjabi: ਕਿੜਲੀ), "jhiti piti" (Oriya: ଝିଟିପିଟି), "zethi" (Assamese: জেঠী), "thikthikiaa" (Maithili: ठिकठिकिया), "paal" (Marathi: पाल), "gawli" or "palli" (Malayalam: ഗവ്ളി (gawli), പല്ലി (palli), Tamil: பல்லி (palli)), Telugu: బల్లి (balli), Kannada: ಹಲ್ಲಿ (halli), "ali" (Sylheti: ꠀꠟꠤ). In West Bengal and Bangladesh they are called "tiktiki" (Bengali: টিকটিকি) as the sound is perceived as "tik tik tik". In Sri Lanka they are called "huna" in singular form (Sinhalese: හුනා). In Central America they are sometimes called "Limpia Casas" (Spanish: Housecleaners) because they reduce the amount of insects and other arthropods in their homes and also called 'qui-qui' because of the sound they make.

House geckos in captivity

House geckos can be kept as pets in a vivarium with a clean substrate, and typically require a heat source and a place to hide in order to regulate their body temperature, and a system of humidifiers and plants to provide them with moisture.

The species will cling to vertical or even inverted surfaces when at rest. In a terrarium they will mostly be at rest on the sides or on the top cover rather than placing themselves on plants, decorations or on the substrate, thus being rather conspicuous.

House geckos are also used as a food source for some snakes.

Superstition

Geckos are considered poisonous in many parts of the world. In Southeast Asia, geckos are believed to be carriers of good omen.[citation needed] In the Philippines, geckos making a ticking sound are believed to indicate an imminent arrival of a visitor or a letter. [32]

In Yemen and other Arab countries, it is believed that skin disease result from geckos walking over the face of someone who is asleep.[citation needed]

An elaborate system of predicting good and bad omens based on the sounds made by geckos, their movement and the rare instances when geckos fall from roofs has evolved over centuries in India.[33][34] In some parts of India, the sound made by geckos is considered a bad omen; while in West Bengal, Bangladesh and Nepal, it is considered to be an endorsement of the truthfulness of a statement made just before, because the sound "tik tik tik" coincides with "thik thik thik", which in many Indian languages (e.g. Bengali), means "right right right", i.e., a three-fold confirmation. The cry of a gecko from an east wall as one is about to embark on a journey is considered auspicious, but a cry from any other wall is supposed to be inauspicious.[citation needed] A gecko falling on someone's right shoulder is considered good omen, but a bad omen if it drops on the left shoulder. In Punjab, it is believed that contact with the urine of a gecko will cause leprosy.[35] In some places in India, it is believed that watching a lizard on the eve of Dhanteras is a good omen or a sign of prosperity.[citation needed]

Notes

- ^ Ota, H. & Whitaker, A.H. 2010. Hemidactylus frenatus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2010: e.T176130A7184890. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2010-4.RLTS.T176130A7184890.en. Downloaded on 08 June 2018.

- ^ "ITIS Standard Report Page: Hemidactylus frenatus". ITIS Report. ITIS-North America. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ^ a b c Newbery, Brock (2007). "Presence of Asian House Gecko Hemidactylus frenatus across an urban gradient in Brisbane: influence of habitat and potential for impact on native gecko species". Pest or Guest: The Zoology of Overabundance: 59–65.

- ^ Keim, Lauren (2002). "The spatial distribution of the introduced Asian House Gecko (Hemidactylus frenatus) across suburban/forest edges". Unpublished Honours Thesis, Department of Zoology and Entomology, the University of Queensland: 65.

- ^ a b c Marcellini, Dale (1971). "Activity Patterns of the Gecko Hemidactylus frenatus". Copeia. 4: 631–635 – via American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists.

- ^ McKay, James; Griffiths, Anthony; Crase, Beth (2009). "Distribution and Habitat Use by Hemidactylus frenatus Dumeril and Bibron (Gekkonidae) in the Northern Territory, Australia". The Beagle: Records of the Museums and Art Galleries of the Northern Territory: 25.

- ^ a b c Gallina-Tessaro, Patricia; Ortega-Rubio, Alfredo; Alvarez-Cardenas, Sergio; Arnaud, Gustavo (1998). "Colonization of Socorro Island (Mexico), by the tropical house gecko Hemidactylus frenatus (Squamata:Gekkonidae)". Review of Tropical Biology. 47: 237–238.

- ^ a b c d e Rodder, Dennis; Sole, Micro; Bohme, Wolfgang (2008). "Predicting the potential distributions of two alien invasive Housegeckos (Gekkonidae: Hemidactylus frenatus, Hemidactylus mabouia)". North-Western Journal of Ecology. 4: 236–246.

- ^ a b c d e f g Case, T; Bolger, T; Petren, K (1994). "Invasions and competitive displacement among house geckos in the tropical pacific". Ecology. 75 (2): 464–477. doi:10.2307/1939550. JSTOR 1939550.

- ^ a b c d e Petren, K; Bolger, D; Case, T (1993). "Mechanisms in the Competitive Success of an invading gecko over an asexual native". Science. 159: 345–357.

- ^ a b Petren, K; Case, T (1996). "An experimental demonstration of exploitation competition in an ongoing invasion". Ecology. 77: 118–132. doi:10.2307/2265661. JSTOR 2265661.

- ^ a b Dame, Elizabeth; Petren, Kenneth (2006). "Behavioural mechanisms of invasion and displacement in Pacific island geckos (Hemidactylus)". Animal Behaviour. 71 (5): 1165–1173. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2005.10.009.

- ^ a b Cole, Nik; Jones, Carl; Harris, Stephen (2005). "The need for enemy-free space: The impact of an invasive gecko on island endemics". Biological Conservation. 125 (4): 467–474. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2005.04.017.

- ^ Hoskin, Conrad (2011). "The invasion and potential impact of the Asian House Gecko (Hemidactylus frenatus) in Australia". Austral Ecology. 36 (3): 240–251. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9993.2010.02143.x.

- ^ Cogger, H. G. (1992). Reptiles and Amphibians of Australia. Chatswood, NSW: Reed Books.

- ^ Tyler, M. J. (1961). "The diet and feeding habits of Hemidactylus frenatus (Dumeril and Bibron) (Reptilia: Gekkonidae) at Rangoon, Burma". Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia. 84: 45–49.

- ^ Cameron, S.F.; Wynn, M.L.; Wilson, R.S. (2013). "Sex-specific trade-offs and compensatory mechanisms: bite force and sprint speed pose conflicting demands on the design of geckos (Hemidactylus frenatus)". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 216 (Pt 20): 3781–3789. doi:10.1242/jeb.083063. PMID 23821718.

- ^ Greer, A.E. (1989). The Biology and Evolution of Australian Lizards. Chipping Norton, NSW: Surrey Beatty & Sons Pty Ltd.

- ^ a b Snyder, G.K.; Weathers, W.W. (1976). "Physiological responses to temperature in the tropical lizard Hemidactylus frenatus (Sauria: Gekkonidae)". Herpetologica. 32: 252–256.

- ^ Licht, P; Dawson, W.R.; Shoemaker, V.H.; Main, A.R. (1966). "Observations on thermal relations of Western Australian Lizards". Copeia: 97–110.

- ^ a b Werner, Yehudah. "Do gravid females of oviparous gekkonid lizards maintain elevated body temperatures? Hemidactylus frenatus and Lepidodactylus lugubris on Oahu". Amphibia-Reptilia.

- ^ Bustard, Robert (1970). "The population ecology of the Australian gekkonid lizard Heteronotia binoei in an exploited forest". Journal of Zoology. 162.

- ^ a b Church, Gilbert. "The Reproductive Cycles of the Javanese House Geckos, Cosymbotus platyurus, Hemidactylus frenatus, and Peropus mutilatus". Copeia. 62: 262–269.

- ^ a b c Murphy-Walker, S.; Haley, S. R. (1996). "Functional Sperm Storage Duration in Female Hemidactylus Frenatus (Family Gekkonidae)". Herpetologica. 32: 365–373.

- ^ Yamamoto, Yurie; Hidetoshi, OTA (2006). "Long-term functional sperm storage by a female common House Gecko, Hemidactylus Frenatus, from the Ryukyu Archipelago, Japan". Current Herpetology. 25: 39–40. doi:10.3105/1345-5834(2006)25[39:LFSSBA]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ a b c Marcellini, Dale (1974). "Acoustic Behaviour of the gekkonid lizard, Hemidactylus frenatus". Herpetologica. 30: 44–52.

- ^ Marcellini, Dale (1977). "The Function of vocal display of the lizard Hemidactylus frenatus (Sauria:Gekkonidae)". Animal Behaviour. 25: 414–417. doi:10.1016/0003-3472(77)90016-1.

- ^ Darevsky, I.S.; Kupriyanova, L.A.; Roschchin, V.V. (1984). "A New All-Female Triploid Species of Gecko and Karyological Data on the Bisexual Hemidactylus frenatus from Vietnam". Journal of Herpetology. 18 (3): 277–284. doi:10.2307/1564081. JSTOR 1564081.

- ^ a b King, Max (1978). "A New Chromosome Form of Hemidactylus Frenatus (Dumeril and Bibron)". Herpetologica. 34: 216–218.

- ^ Storr, G.M. (1978). "Seven New Gekkonid Lizards from Western Australia". Records of the Western Australian Museum. 6.

- ^ Tiyapan, Kittisak Nui (20 April 2018). Thai Grammar, Poetry and Dictionary, in a New Romanised System (in Thai). Lulu.com. p. 102. ISBN 9789741718610 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Mga Hayop (The Animals)". Northern Illinois University. Retrieved 2019-06-24.

- ^ "ഗൗളിശാസ്ത്രം | Mashithantu | English Malayalam Dictionary മഷിത്തണ്ട് | മലയാളം < - > ഇംഗ്ലീഷ് നിഘണ്ടു". Dictionary.mashithantu.com. Retrieved 2013-12-14.

- ^ "Hindu Omens". Oldandsold.com. Retrieved 2013-12-14.

- ^ "The Folklore of Geckos : Ethnographic Date from South and West Asia". Nirc.nanzan-u.ac.jp. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

References

- Cook, Robert A. 1990 Range extension of the Darwin house gecko, Hemidactylus frenatus. Herpetofauna (Sydney) 20 (1): 23-27

- Darevsky I S; Kupriyanova L A; Roshchin V V 1984 A new all-female triploid species of gecko and karyological data on the bisexual Hemidactylus frenatus from Vietnam. Journal of Herpetology 18 (3) : 277-284

- Edgren, Richard A. 1950 Notes on the Neotropical population of Hemidactylus frenatus Schlegel Natural History Miscellanea (55): 1-3

- Edgren, R. A. 1956 Notes on the neotropical population of Hemidactylus frenatus Schlegel. Nat. Hist. Misc. 55: 1-3.

- Jerdon, T.C. 1853 Catalogue of the Reptiles inhabiting the Peninsula of India. Part 1. J. Asiat. Soc. Bengal xxii [1853]: 462-479

- McCoy, C. J.;Busack, Stephen D. 1970 The lizards Hemidactylus frenatus and Leiolopisma metallica on the Island of Hawaii Herpetologica 26 (3): 303

- Norman, Bradford R. 2003 A new geographical record for the introduced house gecko, Hemidactylus frenatus, at Cabo San Lucas, Baja California Sur, Mexico, with notes on other species observed. Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society. 38(5):98-100 [erratum in 38(7):145]

- Ota H 1989 Hemidactylus okinawensis Okada 1936, junior synonym of H. frenatus in Duméril & Bibron 1836. J. Herpetol. 23 (4): 444-445

- Saenz, Daniel;Klawinski, Paul D. 1996 Geographic Distribution. Hemidactylus frenatus. Herpetological Review 27 (1): 32

External links

Media related to Hemidactylus frenatus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hemidactylus frenatus at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Hemidactylus frenatus at Wikispecies

Data related to Hemidactylus frenatus at Wikispecies- Interaction of Asian House geckos and Wasps

- Asian House Gecko in Laguna de Apoyo Nature Reserve, Nicaragua[permanent dead link]

- IUCN Red List least concern species

- Hemidactylus

- Reptiles of Asia

- Fauna of the Marshall Islands

- Reptiles of Thailand

- Reptiles of Japan

- Reptiles of China

- Reptiles of Taiwan

- Reptiles of Cambodia

- Reptiles of Pakistan

- Reptiles of the Philippines

- Reptiles of Indonesia

- Reptiles described in 1836

- Reptiles of India

- Geckos of Australia