Chinese nationalism

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: lede long and confusing. (October 2019) |

Chinese nationalism is the form of nationalism in China which asserts that the Chinese people are a nation and promotes the cultural and national unity of the Chinese. It distinguishes from the Han nationalism, which used to seek the independence of ethnic Chinese from Qing Empire and now holds a chauvinism or racialism attitude to ethnic minorities in China.

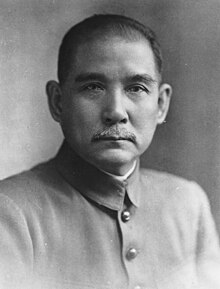

Chinese nationalism emerged in the last years of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), especially in response to the humiliation of defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895, and the invasion and pillaging of Beijing by eight nations who were stopping the attacks on foreigners by the Boxer Rebellion of 1900. In both cases the aftermath included massive financial reparations, and special privileges granted to foreigners. The longtime image of the superior celestial kingdom at the center of the universe had crashed; last-minute efforts to modernize and strengthen the old system were unsuccessful. Liang Qichao failed to reform the Qing government in 1896 and was later expelled to Japan, where he translated the ideas of nationalism into Chinese and himself became a nationalist. As a monarchist, Liang and other monarchists argued the Chinese empire should sustain as a whole (Chinese nation), and debates with those anti-Manchu revolutionaries and Han chauvinist such as Sun Yat-sen, who later accepted all peoples in China, including Manchu, were member of a united Chinese nation in 1912 when the Manchu government was overthrown.

During the World War I China joined the Allies in order to recover its sovereignty from Germany. Although China was on the winning side, it was severely humiliated again by the Versailles Treaty of 1919, which transferred the special privileges that Germany had gained not back to China but to its bitter enemy Japan. This latest humiliation sparked the May Fourth Movement of 1919 exploded into nation-wide protests that spurred an upsurge of Chinese nationalism, as well as a shift towards political mobilization and away from cultural activities, and a move towards a mass base and away from traditional intellectual and political elites. Since the overthrown of the old Empire in 1912, China have been ruled by regional warlords, but now a strong sense of national unity was reflected in a large-scale military campaign, led by the Kuomintang (KMT). The goals of nationalism were achieved by building a strong national republican government that overpowered the provincial warlords, and sharply reduced special privileges for foreigners. As for well-being, the people were still mired deep in poverty, and threatened repeatedly by famines and epidemics.

Ethnic rivalries became a major factor. The Han element comprised a large majority of the population, but there were numerous minority ethnic groups. By 1930, Chiang Kai-shek (1887-1975) had expelled the Communists from the KMT coalition. However, he failed to destroy the movement as Mao Zedong (1893 to 1976) led its escape on its Long March and set up a rival state in distant provinces in northwest China. Japan struck again in 1931, seizing control of Manchuria. The League of Nations investigated and announced this action, but Japan quit the League and no action was taken as the Japanese army grew stronger, it ignored its government in Tokyo. In 1937 it opened up full-scale undeclared war against China, and soon captured practically all of the major cities and coastal areas. The Nationalist government was badly defeated and escaped into remote areas in southwestern China. After Japan was defeated in World War II in 1945, a refreshed nationalism was on display as China recovered lost territories including Manchuria and Taiwan. It received the prestige of a veto power on the new United Nations Security Council. However the civil war between nationalists and communists resumed. The Communists were victorious in 1949, as the KMT elements fled to Taiwan, proclaiming that island as the legitimate Republic of China. The Communists now had an opportunity to use nationalistic traditions to build upon. The powerful national government worked hard to suppress separatism in Tibet and among the Uyghurs, a Turkic minority in the far-west province of Xinjiang. Nationalist forces tried to reduce the semi-independence in Hong Kong, but were strongly opposed by massive demonstrations in 2018. Populist nationalism became a major factor in domestic and foreign policy in the 21st century, especially as propounded by Xi Jinping who became the General Secretary of the Communist Party of China in 2012.

National consciousness

There have been versions of a Chinese state for around 4,000 years. The Chinese concept of the world was largely a division between the civilized world and the barbarian world and there was little concept of the belief that Chinese interests were served by a powerful Chinese state. Commenter Lucian Pye has argued that the modern "nation state" is fundamentally different from a traditional empire, and argues that dynamics of the current People's Republic of China (PRC) – a concentration of power at a central point of authority – share an essential similarity with the Ming and Qing Empires.[1] Chinese nationalism as it emerged in the early 20th century was based on the experience of European nationalism, especially as viewed and interpreted by Sun Yat-sen. The key factor in European nationalism was tradition – some of them newly manufactured – of a cultural identity based primarily on language and ethnicity. Chinese nationalism was rooted in the long historic tradition of China as the center of the world, in which all other states were offshoots and owed some sort of deference. That sense of superiority underwent a series of terrible shocks in the 19th century, including large-scale internal revolts, and more grievously the systematic Gaining of special rights and privileges by foreign nations, led by Britain, France, Russia and Japan, who proved over and over again their military superiority, based on modern technology that was lacking in China. It was a matter of humiliation one after another,, the loss of faith in the Manchu Dynasty. Most dramatic watershed came in 1900, in the wake of the invasion, capture, and pillaging of the national capital by an eight nation coalition that punished China for the Boxer Rebellion.. [2] Ethnic nationalism was in any case unacceptable to the ruling Manchu elite-- they were foreigners who conquered China, and maintained their own language and traditions. Most citizens had multiple identities, of which the locality was more important than the nation as a whole. [3] Anyone who wanted to rise in government Non-military service had to be immersed in Confucian classics, and pass a very difficult test. If accepted, they would be rotated around the country, so the bureaucrats did not identify with the locality. The depth of two-way understanding and trust developed by European political leaders and their followers did not exist.[4]

Ideological basis

Chinese nationalism has drawn from extremely diverse ideological sources including traditional Chinese thinking, American progressivism, Marxism, and Russian ethnological thought. The ideology also presents itself in many different and often conflicting manifestations. These manifestations have included the Three Principles of the People in the Republic of China, the Maoist dogma of the Communist Party of China, the anti-government views of students in the Tiananmen protests of 1989, the fascist blueshirts of the Kuomintang, and Japanese collaborationism under Wang Jingwei.[5]

Although Chinese nationalists have agreed on the desirability of a centralized Chinese state, almost every other question has been the subject of intense and sometimes bitter debate. Among the questions on which Chinese nationalists have disagreed is what policies would lead to a strong China, what is the structure of the state and its goal, what the relationship should be between China and foreign powers, and what should be the relationships between the majority Han Chinese, minority groups, and overseas Chinese.[6]

The vast variation in how Chinese nationalism has been expressed has been noted by commentator Lucian Pye who argues that this reveals a lack of content in the Chinese identity. However, others have argued that the ability of Chinese nationalism to manifest itself in many forms is a positive trait in that it allows the ideology to transform itself in response to internal crises and external events.[7]

Although the variations among conceptions of Chinese nationalism are great, Chinese nationalist groups maintain some similarities. Chinese nationalistic ideologies all regard Sun Yat-Sen very highly, and tend to claim to be ideological heirs of the Three Principles of the People. Some Chinese nationalists also see Chiang Kai-shek, the longtime President of the Republic of China, as the leading nationalist figure. In addition, Chinese nationalistic ideologies tend to regard both democracy and science as positive forces, although they often have radically different notions of what democracy means.[8] Kuomintang recruits pledged:

- from this moment I will destroy the old and build the new, and fight for the self-determination of the people, and will apply all my strength to the support of the Chinese Republic and the realization of democracy through the Three Principles, ... for the progress of good government, the happiness and perpetual peace of the people, and for the strengthening of the foundations of the state in the name of peace throughout the world.[9]

Ethnicity

Defining the relationship between ethnicity and the Chinese identity has been a very complex issue throughout Chinese history. In the 17th century, with the help of Ming Chinese rebels, the Manchus conquered the China proper and set up the Qing dynasty. Over the next centuries they would incorporate groups such as the Tibetans, the Mongols, and the Uyghurs into territories which they controlled. The Manchus were faced with the issue of maintaining loyalty among the people they ruled while at the same time maintaining a distinctive identity. The main method by which they accomplished control of the Chinese heartland was by portraying themselves as enlightened Confucian sages part of whose goal was to preserve and advance Chinese civilization. Over the course of centuries the Manchus were gradually assimilated into the Chinese culture and eventually many Manchus identified themselves as a people of China.

The complexity of the relationship between ethnicity and the Chinese identity can be seen during the Taiping rebellion in which the rebels fought fiercely against the Manchus on the ground that they were barbarian foreigners while at the same time others fought just as fiercely on behalf of the Manchus on the grounds that they were the preservers of traditional Chinese values. It was during this time that the concept of Han Chinese came into existence as a means of describing the majority Chinese ethnicity.

In 1909, the Law of Nationality of Great Qing ("大清国籍条例" in Chinese) was published by the Manchu government, which defined Chinese with the following rules: 1.born in China while his/her father is a Chinese; 2. born after his/her father's death while his/her father is a Chinese at his death; 3.his/her mother is a Chinese while his/her father's nationality is unclear or stateless.[10]

In 1919, the May Fourth Movement grew out of student protests to the Treaty of Versailles, especially its terms allowing Japan to keep territories surrendered by Germany after the Siege of Tsingtao, and spurned upsurges of Chinese nationalism amongst the protests.

The official Chinese nationalistic view in the 1920s and 1930s was heavily influenced by modernism and social Darwinism, and included advocacy of the cultural assimilation of ethnic groups in the western and central provinces into the "culturally advanced" Han state, to become in name as well as in fact members of the Chinese nation. Furthermore, it was also influenced by the fate of multi-ethnic states such as Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire. It also became a very powerful force during the Japanese occupation of Coastal China during the 1930s and 1940s and the atrocities committed then.

Over the next decades Chinese nationalism was influenced strongly by Russian ethnographic thinking, and the official ideology of the PRC asserts that China is a multi-ethnic state, and Han Chinese, despite being the overwhelming majority (over 95% in the mainland), they are only one of many ethnic groups of China, each of whose culture and language should be respected. However, many critics argue that despite this official view, assimilationist attitudes remain deeply entrenched, and popular views and actual power relationships create a situation in which Chinese nationalism has in practice meant Han dominance of minority areas and peoples and assimilation of those groups.

During the 1960s and 1970s, Chinese nationalism within mainland China became mixed with the rhetoric of Marxism, and nationalistic rhetoric become in large part subsumed into internationalist rhetoric. On the other hand, Chinese nationalism in Taiwan was primarily about preserving the ideals and lineage of Sun Yat-sen, the party he founded, the Kuomintang (KMT), and anti-Communism. While the definition of Chinese nationalism differed in the Republic of China (ROC) and PRC, both were adamant in claiming Chinese territories such as Senkaku (Diaoyutai) Islands.

In the 1990s, rising economic standards, the dissolution of Soviet Union, and the lack of any other legitimizing ideology has led to what most observers see as a resurgence of nationalism within China.

Ethnic minorities

Chinese Muslims and Uighurs

Chinese Muslims have played an important role in Chinese nationalism. Chinese Muslims, known as Hui people, are a mixture of the descendants of foreign Muslims like Arabs and Persians, mixed with Han Chinese who converted to Islam. Chinese Muslims are sinophones, speaking Chinese and practicing Confucianism.

Hu Songshan, a Muslim Imam from Ningxia, was a Chinese nationalist and preached Chinese nationalism and unity of all Chinese people, and also against imperialism and foreign threats.[11][11] He even ordered the Chinese Flag to be saluted during prayer, and that all Imams in Ningxia preach Chinese nationalism. Hu Songshan led the Ikhwan, the Chinese Muslim Brotherhood, which became a Chinese nationalist, patriotic organization, stressing education and independence of the individual.[11][12][13] Hu Songhan also wrote a prayer in Arabic and Chinese, praying for Allah to support the Chinese Kuomintang government and defeat Japan.[14] Hu Songshan also cited a Hadith (聖訓), a saying of the prophet Muhammad, which says "Loving the Motherland is equivalent to loving the Faith" (“愛護祖國是屬於信仰的一部份”). Hu Songshan harshly criticized those who were non-patriotic and those who taught anti nationalist thinking, saying that they were fake Muslims.

Ma Qixi was a Muslim reformer, leader of the Xidaotang, and he taught that Islam could only be understood by using Chinese culture such as Confucianism. He read classic Chinese texts and even took his cue from Laozi when he decided to go on Hajj to Mecca.

Ma Fuxiang, a Chinese Muslim general and Kuomintang member, was another Chinese nationalist. Ma Fuxiang preached unity of all Chinese people, and even non-Han Chinese people such as Tibetans and Mongols to stay in China. He proclaimed that Mongolia and Tibet were part of the Republic of China, and not independent countries.[15] Ma Fuxiang was loyal to the Chinese government, and crushed Muslim rebels when ordered to. Ma Fuxiang believed that modern education would help Hui Chinese build a better society and help China resist foreign imperialism and help build the nation. He was praised for his "guojia yizhi"(national consciousness) by non-Muslims. Ma Fuxiang also published many books, and wrote on Confucianism and Islam, having studied both the Quran and the Spring and Autumn Annals.

Ma Fuxiang had served under the Chinese Muslim general Dong Fuxiang, and fought against the foreigners during the Boxer Rebellion.[16][17] The Muslim unit he served in was noted for being anti foreign, being involved in shooting a Westerner and a Japanese to death before the Boxer Rebellion broke out.[18] It was reported that the Muslim troops were going to wipe out the foreigners to return a golden age for China, and the Muslims repeatedly attacked foreign churches, railways, and legations, before hostilities even started.[19] The Muslim troops were armed with modern repeater rifles and artillery, and reportedly enthusiastic about going on the offensive and killing foreigners. Ma Fuxiang led an ambush against the foreigners at Langfang and inflicted many casualties, using a train to escape. Dong Fuxiang was a xenophobe and hated foreigners, wanting to drive them out of China.

Various Muslim organizations in China like China Islamic Association (Zhongguo Huijiao Gonghui) and the Chinese Muslim Association were sponsored by the Kuomintang.

Chinese Muslim imams had synthesized Islam and Confucianism in the Han Kitab. They asserted that there was no contradiction between Confucianism and Islam, and no contradiction between being a Chinese national and a Muslim. Chinese Muslim students returning from study abroad, from places such as Al-Azhar University in Egypt learned about nationalism and advocated Chinese nationalism at home. One Imam, Wang Jingzhai, who studied at Mecca, translated a Hadith, or saying of Muhammad, "Aiguo Aijiao"- loving the country is equivalent to loving the faith. Chinese Muslims believed that their "watan" Arabic: وطن, lit. 'country; homeland' was the whole of the Republic of China, non-Muslims included.[20]

General Bai Chongxi, the warlord of Guangxi, and a member of the Kuomintang, presented himself as the protector of Islam in China and harbored Muslim intellectuals fleeing from the Japanese invasion in Guangxi. General Bai preached Chinese nationalism and anti-imperialism. Chinese Muslims were sent to Saudi Arabia and Egypt to denounce the Japanese. Translations from Egyptian writings and the Quran were used to support propaganda in favour of a Jihad against Japan.[20]

Ma Bufang, a Chinese Muslim general who was part of the Kuomintang, supported Chinese nationalism and tolerance between the different Chinese ethnic groups. The Japanese attempted to approach him however their attempts at gaining his support were unsuccessful. Ma Bufang presented himself as a Chinese nationalist to the people of China, fighting against British Imperialism, to deflect criticism by opponents that his government was feudal and oppressed minorities like Tibetans and Buddhist Mongols. He presented himself as a Chinese nationalist to his advantage to keep himself in power as noted by the author Erden.[21][22]

In Xinjiang, the Chinese Muslim general Ma Hushan supported Chinese nationalism. He was chief of the 36th Division of the National Revolutionary Army. He spread anti-Soviet, and anti-Japanese propaganda, and instituted a colonial regime over the Uighurs. Uighur street names and signs were changed to Chinese, and the Chinese Muslim troops imported Chinese cooks and baths, rather than using Uighur ones.[23] The Chinese Muslims even forced the Uighur carpet industry at Khotan to change its design to Chinese versions.[24] Ma Hushan proclaimed his loyalty to Nanjing, denounced Sheng Shicai as a Soviet puppet, and fought against Soviet invasion in 1937.[23]

The Tungans (Chinese Muslims, Hui people) had anti-Japanese sentiment.[23][25]

General Ma Hushan's brother Ma Zhongying denounced separatism in a speech at Id Kah Mosque and told the Uighurs to be loyal to the Chinese government at Nanjing.[26][27][28] The 36th division had crushed the Turkish Islamic Republic of East Turkestan, and the Chinese Muslim general Ma Zhancang beheaded the Uighur emirs Abdullah Bughra and Nur Ahmad Jan Bughra.[29][28] Ma Zhancang abolished the Islamic Sharia law which was set up by the Uighurs, and set up military rule instead, retaining the former Chinese officials and keeping them in power.[28] The Uighurs had been promoting Islamism in their separatist government, but Ma Hushan eliminated religion from politics. Islam was barely mentioned or used in politics or life except as a vague spiritual focus for unified opposition against the Soviet Union.[23]

The Uighur warlord Yulbars Khan was pro-China and supported the Republic of China.[30] The Uighur politician Masud Sabri served as the Governor of Xinjiang Province from 1947 to 1949.[31]

Tibetans

Pandatsang Rapga, a Tibetan politician, founded the Tibet Improvement Party with the goal of modernisation and integration of Tibet into the Republic of China.[32][33]

The 9th Panchen Lama, Thubten Choekyi Nyima, was considered extremely "pro-Chinese", according to official Chinese sources.[34][35][36]

Mongols

Many of the Chinese troops used to occupy Mongolia in 1919 were Chahar Mongols, which has been a major cause for animosity between Khalkhas and Inner Mongols.[37]

In Taiwan

One common goal of current Chinese nationalists is the unification of mainland China and Taiwan. While this was the common stated goal of both the People's Republic of China and the Republic of China (ROC) before 1991, both sides differed sharply on the form of unification.

In Taiwan there is a general consensus to support the status quo of Taiwan's de facto independence as a separate nation. Despite this, the relationship between Chinese nationalism and Taiwan remains controversial, involving symbolic issues such as the use of "The Republic of China" as the official name of the government on Taiwan and the use of the word "China" in the name of Government-owned corporations. Broadly speaking, there is little support in Taiwan for unification. Overt support for formal independence is also muted due to the PRC's insistence on military action should Taiwan make such a formal declaration. The argument against unification is partly over culture and whether democratic Taiwanese should see themselves as Chinese or Taiwanese; and partly over a mistrust of the authoritarian Chinese Communist Party (CPC), its human rights record, and its de-democratizing actions in Hong Kong (e.g. 2014–15 Hong Kong electoral reform, which sparked the Umbrella Movement). These misgivings are particularly prevalent amongst younger generations of Taiwanese, who generally view both the CPC and the KMT as obsolete and consider themselves to have little or no connection to China, whose government they perceive as a foreign aggressor.[citation needed]

Overseas Chinese

Chinese nationalism has had mutable relationships with Chinese living outside of Mainland China and Taiwan. Overseas Chinese were strong supporters of the Xinhai Revolution.

After decolonization, overseas Chinese were encouraged to regard themselves as citizens of their adopted nations rather than as part of the Chinese nationality. As a result, ethnic Chinese in Thailand, Singapore, and Malaysia have sharply divided the concept of ethnic Chinese from the concept of "political Chinese" and have explicitly rejected being part of the Chinese nationality.

During the 1960s, the People's Republic of China and Republic of China (ROC) maintained different attitudes toward overseas Chinese. In the eyes of the PRC government, overseas Chinese were considered capitalist agents; in addition, the PRC government also thought that maintaining good relations with southeast Asian governments was more important than maintaining the support of overseas Chinese. By contrast, the ROC desired good relations with overseas Chinese as part of an overall strategy to avoid diplomatic isolation and maintain its claim to be the sole legitimate government of China.

With the reforms under Deng Xiaoping, the PRC's attitude toward overseas Chinese became much more favourable, and overseas Chinese were seen as a source of capital and expertise. In the 1990s, the PRC's efforts toward overseas Chinese became mostly focused on maintaining the loyalty of "newly departed overseas Chinese", which consisted of mostly graduate students having emigrated, mostly to the United States. Now, there are summer camps in which overseas Chinese youths may attend to learn first-hand about Chinese culture. In 2013, "100 overseas Chinese youth embarked on their root-seeking journey in Hunan."[38] Textbooks for Chinese schools are distributed by the government of the People's Republic of China.

Opposition

In addition to the Taiwan independence movement, Hong Kong independence movement and Japanese nationalism, there are a number of ideologies which exist in opposition to Chinese nationalism.

Some opponents have asserted that Chinese nationalism is inherently backward and is therefore incompatible with a modern state. Some claim that Chinese nationalism is actually a manifestation of beliefs in Han Chinese ethnic superiority (also known as Sinocentrism),[39] though this is hotly debated. While opponents have argued that reactionary nationalism is evidence of Chinese insecurity or immaturity and that it is both unnecessary and embarrassing to a powerful nation, Chinese nationalists assert that Chinese nationalism was in many ways a result of Western imperialism and is fundamental to the founding of a modern Chinese state that is free from foreign domination. Certain Japanese nationalist groups are anti-Chinese.

Northern and Southern

Edward Friedman has argued[40] that there is a northern governmental, political, bureaucratic Chinese nationalism that is at odds with a southern, commercial Chinese nationalism. This division is rejected by most Chinese and many non-Chinese scholars, who believe that Friedman has overstated the differences between the north and the south, and point out that the divisions within Chinese society do not fall neatly into "north-south" divisions.

For example, Dr. Sun Yat Sen, leader of the Chinese Nationalist Party, known as the father of modern China, was a southern Chinese with Cantonese-Hakka ancestry. He advocated pan-Han Chinese nationalism against the ruling Manchu-led Qing dynasty and was influential in the overthrow of the Qing dynasty. He is widely revered in both mainland China and Taiwan regardless of northern or southern orientation.

Populism

During the 1990s, Chinese intellectuals have vigorously debated the political meaning and significance of the rising nationalism in China. From their debates has emerged a multifarious populist nationalism which argues that anti-imperialist nationalism in China has provided a valuable public space for popular participation outside the country's political institutions and that nationalist sentiments under the postcolonial condition represent a democratic form of civic activity. Advocates of this theory promote nationalism as an ideal of populist politics and as an embodiment of the democratic legitimacy that resides in the will of the people.

Populist nationalism is a comparatively late development in Chinese nationalism of the 1990s. It began to take recognizable shape after 1996, as a joint result of the evolving nationalist thinking of the early 1990s and the ongoing debates on modernity, postmodernism, postcolonialism, and their political implications-debates that have engaged many Chinese intellectuals since early 1995.

Modern times

The end of the Cold War has seen the revival throughout the world of nationalist sentiments and aspirations. However, nationalist sentiment is not the sole province of the CPC. One truly remarkable phenomenon in the post-Cold War upsurge of Chinese nationalism is that Chinese intellectuals became one of the driving forces.[41] Many well-educated people-social scientists, humanities scholars, writers and other professionals-have given voice to and even become articulators for rising nationalistic discourse in the 1990s. Some commentators have proposed that "positive nationalism" could be an important unifying factor for the country as it has been for other countries.[42]

As an indication of the popular and intellectual origins of recent Chinese nationalist sentiment, all coauthors of China Can Say No, the first in a string of defiant rebuttals to American imperialism [citation needed], are college educated, and most are self-employed (a freelancer, a fruit-stand owner, a poet, and journalists working in the partly market-driven field of Chinese newspapers, periodicals, and television stations).

Chinese nationalism targets against two major groups: Japan, which invaded China in 1931–1945, and Secessionism like Tibetan independence, Xinjiang independence, Taiwanese independence, Hong Kong independence, occasionally Mongolian independence, and their supporters like USA and India. Chinese nationalists deem Taiwanese separatists, Hong Kong separatists, and other similar independence groups in China as hanjian (traitors).

In the 21st century, notable spurs of grassroots Chinese nationalism grew from what the Chinese saw as marginalization of their country from Japan and the Western world. The Japanese history textbook controversies, as well as Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi's visits to the Yasukuni Shrine was the source of considerable anger on Chinese blogs. In addition, the protests following the 2008 Tibetan unrest of the Olympic torch has gathered strong opposition within the Chinese community inside China and abroad. Almost every Tibetan protest on the Olympic torch route was met with a considerable pro-China protest. Because the 2008 Summer Olympics were a major source of national pride, anti-Olympics sentiments are often seen as anti-Chinese sentiments inside China. Moreover, the Sichuan earthquake in 2008 sparked a high sense of nationalism from Chinese at home and abroad. The central government's quick response to the disaster was instrumental in galvanizing general support from the population amidst harsh criticism directed towards China's handling of the Lhasa riots only two months previous. In 2005, anti-Japanese demonstrations were held throughout Asia as a result of events such as the Japanese history textbook controversies. In 2012, Chinese people in mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan held anti-Japanese protests due to the escalating Senkaku Islands dispute.

Another example of modern nationalism in China is the Hanfu movement, which is a Chinese movement in the early 21st century that seeks the revival of Chinese traditional clothing.[43] Some elements of the movement take inspiration from the use of indigenous clothing by ethnic minorities in China, as well as the usage of kimono in Japan and traditional clothing used in India.[44] Credit Suisse has determines through a survey that young Chinese consumers are turning to local brands as a result of growing nationalism. In extreme cases, some Chinese have questioned whether or not Chinese companies are actually Chinese. [45][46][47][48][49]

Internet vigilantism

Since the state controlled media has control over most media outlet, the Internet is one of the rare places where Chinese nationalists can freely express their feelings. While the government is known for shutting down controversial blogs, it is impossible to completely censor the Internet and all websites that may be deemed controversial. Chinese Internet users frequently write nationalistic topics online on websites such as Tianya.cn. Some web-based media such as a webcomic named Year Hare Affair also features nationalistic ideas. Many nationalists look for news of people whom they consider to be traitors to China, such as the incident with Grace Wang from Duke University,[50] a Chinese girl who allegedly tried to appease to both sides during the debate about Tibet before the 2008 Summer Olympics. She was labeled as a traitor by online Internet vigilantes, and even had her home back in Qingdao, China, desecrated. Her parents had to hide for a while before the commotion died down.

In response to protests during the 2008 Olympic Torch Relay and accusations of bias from the western media, Chinese blogs, forums and websites became filled with nationalistic material, while flash counter-protests were generated through electronic means, such as the use of SMS and IM. One such site, Anti-CNN, claimed that news channels such as CNN and BBC only reported selectively, and only provided a one-sided argument regarding the 2008 Tibetan unrest.[51] Chinese hackers have claimed to have attacked the CNN website numerous times, through the use of DDoS attacks.[52] Similarly, the Yasukuni Shrine website was hacked by Chinese hackers during late 2004, and another time on 24 December 2008.[53]

Xi Jinping and the "Chinese Dream"

As Xi Jinping became the General Secretary of the Communist Party that solidified his control after 2012, the Communist Party has used the phrase "Chinese Dream" to describe his overarching plans for China. Xi first used the phrase during a high-profile visit to the National Museum of China on 29 November 2012, where he and his Standing Committee colleagues were attending a "national revival" exhibition. Since then, the phrase has become the signature political slogan of the Xi era.[54] In the public media, the China dream and nationalism are interwoven. [55] In diplomacy, the China dream and nationalism have been closely linked to the Belt and Road Initiative. Peter Ferdinand argues that it thus becomes a dream about a future in which China "will have recovered its rightful place."[56]

See also

- Adoption of Chinese literary culture

- Anti-American sentiment in China

- Anti-Japanese sentiment in China

- Anti-Korean sentiment in China

- Anti-Western sentiment in China

- Boxer Rebellion

- Chinese Century

- Chinese imperialism

- Chinese unification

- De-Sinicization

- Fenqing

- Han chauvinism

- Hui pan-nationalism

- List of tributaries of China

- Manchurian nationalism

- May Fourth Movement

- Pax Sinica

- Sinicization

- Sinocentrism

- Sinophile

- Zhonghua minzu

References

- ^ Pye, Lucian W.; Pye, Mary W. (1985). Asian power and politics: the cultural dimensions of authority. Harvard University Press. p. 184.

- ^ Mary Clabaugh Wright, ed. China and revolution: the first phase, 1900-1913 (1968) pp 1-23.

- ^ Odd Arne Westad, Restless Empire: China and the Worlds in 1750 (2012) p. 29-30.

- ^ On how Confucianism was an invented tradition in China see Lionel M. Jensen, Manufacturing Confucianism: Chinese traditions & universal civilization (Duke UP, 1997) pp 3-7.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Cabestan, "The many facets of Chinese nationalism." China perspectives (2005) 2005.59 online.

- ^ Cabestan, "The many facets of Chinese nationalism." China perspectives (2005)

- ^ Lucian W. Pye, "How China's nationalism was Shanghaied." Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs 29 (1993): 107-133.

- ^ Michael Dillon, China: A Cultural and Historical Dictionary (2017), pp 74, 160, 302, 316

- ^ Hans Kohn, Nationalism: Its Meaning and History (1955) p. 87.

- ^ "大清國籍條例" [Law of Nationality of Great Qing]. Wikisource (Chinese version) (in Chinese). Qing government.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c Jonathan Neaman Lipman (2004). Familiar strangers: a history of Muslims in Northwest China. Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 210. ISBN 0-295-97644-6.

- ^ Joint Committee on Chinese Studies (U.S (1987). Papers from the Conference on Chinese Local Elites and Patterns of Dominance, Banff, August 20–24, 1987, Volume 3. p. 30.

- ^ Stéphane A. Dudoignon (2004). Devout societies vs. impious states?: transmitting Islamic learning in Russia, Central Asia and China, through the twentieth century : proceedings of an international colloquium held in the Carré des Sciences, French Ministry of Research, Paris, November 12–13, 2001. Schwarz. p. 69. ISBN 3-87997-314-8.

- ^ Lipman, Familiar Strangers, p 200

- ^ Lipman, Familiar Strangers, p 167

- ^ Lipman, Familiar Strangers, p 169

- ^ Joseph Esherick (1988). The origins of the Boxer Uprising. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-520-06459-1. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Joseph Esherick (1988). The origins of the Boxer Uprising. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 302. ISBN 978-0-520-06459-1. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Ching-shan, Jan Julius Lodewijk Duyvendak (1976). The diary of His Excellency Ching-shan: being a Chinese account of the Boxer troubles. University Publications of America. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-89093-074-8.

- ^ a b Masumi, Matsumoto. "The completion of the idea of dual loyalty towards China and Islam". Archived from the original on 2011-07-24. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Uradyn Erden Bulag (2002). Dilemmas The Mongols at China's edge: history and the politics of national unity. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 48. ISBN 0-7425-1144-8. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Uradyn Erden Bulag (2002). Dilemmas The Mongols at China's edge: history and the politics of national unity. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 49. ISBN 0-7425-1144-8. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ a b c d Andrew D. W. Forbes (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: a political history of Republican Sinkiang 1911–1949. Cambridge, England: CUP Archive. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-521-25514-1. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Andrew D. W. Forbes (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: a political history of Republican Sinkiang 1911–1949. Cambridge, England: CUP Archive. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-521-25514-1. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Forbes (1986), p. 130

- ^ S. Frederick Starr (2004). Xinjiang: China's Muslim borderland. M.E. Sharpe. p. 79. ISBN 0-7656-1318-2.

- ^ James A. Millward (2007). Eurasian crossroads: a history of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. p. 200. ISBN 0-231-13924-1.

- ^ a b c Andrew D. W. Forbes (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: a political history of Republican Sinkiang 1911-1949. Cambridge, England: CUP Archive. pp. 82, 123, 124, 303. ISBN 0-521-25514-7.

- ^ Christian Tyler (2004). Wild West China: the taming of Xinjiang. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. p. 116. ISBN 0-8135-3533-6.

- ^ Andrew D. W. Forbes (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: a political history of Republican Sinkiang 1911-1949. Cambridge, England: CUP Archive. p. 254. ISBN 0-521-25514-7. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Ondřej Klimeš (8 January 2015). Struggle by the Pen: The Uyghur Discourse of Nation and National Interest, c.1900-1949. BRILL. pp. 197–. ISBN 978-90-04-28809-6.

- ^ Melvyn C. Goldstein (1991). A history of modern Tibet, 1913-1951: the demise of the Lamaist state. Vol. Volume 1 of A History of Modern Tibet (reprint, illustrated ed.). University of California Press. p. 450. ISBN 0-520-07590-0. Retrieved 2011-12-27.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Hsiao-ting Lin (2010). Modern China's ethnic frontiers: a journey to the west. Vol. Volume 67 of Routledge studies in the modern history of Asia (illustrated ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 95. ISBN 0-415-58264-4. Retrieved 2011-12-27.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Chinese Materials Center (1982). Who's who in China, 1918-1950: 1931-1950. Vol. Volume 3 of Who's who in China, 1918-1950: With an Index, Jerome Cavanaugh. Chinese Materials Center. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ The China weekly review, Volume 54. Millard Publishing House. 1930. p. 406. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ^ China monthly review, Volume 56. Millard Publishing Co., Inc. 1931. p. 306. Retrieved 2011-06-05.

- ^ Bulag, Uradyn Erden (1998). Nationalism and Hybridity in Mongolia (illustrated ed.). Clarendon Press. p. 139. ISBN 0198233574. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ "100 overseas Chinese youth embark on their root-seeking journey in Hunan-Sino-US". Sino-us.com. 2013-06-24. Retrieved 2016-02-22.

- ^ Zhao, Suisheng. "Chinese Pragmatic Nationalism and Its Foreign Policy Implications" (PDF). Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association. University of Denver. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 January 2015. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ Friedman, Edward (1995). National identity and democratic prospects in socialist China. New York: M. E. Sharpe. pp. 33, 77. ISBN 1-56324-434-9.

- ^ John M. Friend; Bradley A. Thayer (1 November 2018). How China Sees the World: Han-Centrism and the Balance of Power in International Politics. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-1-64012-137-9.

- ^ Niklas Swanstrom. Positive nationalism could prove bond for Chinese Archived 2008-02-27 at the Wayback Machine. May 4, 2005, Baltimore Sun.

- ^ Ying, Zhi (2017). The Hanfu Movement and Intangible Cultural Heritage: considering The Past to Know the Future (MSc). University of Macau/Self-published. p. 12.

- ^ 华, 梅 (14 June 2007). "汉服堪当中国人的国服吗?". People's Daily Online.

- ^ "Lenovo branded 'unpatriotic' by Chinese consumers in nationalistic backlash". South China Morning Post. June 7, 2019.

- ^ "How China's consumer patriotism is hitting US and international brands". South China Morning Post. March 22, 2018.

- ^ Shepard, Wade. "Will Growing Nationalism Kill Foreign Brands In China?". Forbes.

- ^ "Chinese consumers are increasingly preferring to buy domestic: Credit Suisse". CNBC. March 22, 2018.

- ^ Doffman, Zak. "Apple iPhone Sales Down 35% In China As Huawei Soars". Forbes.

- ^ Goldkorn, Jeremy. "Grace Wang". Danwei.org. Retrieved 2016-02-22.

- ^ Anti-CNN website Archived 2008-04-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ SBS Dateline, 6 Aug 2008 Video on YouTube

- ^ "Chinese suspected of attack on Tokyo shrine's Web site". Taipei Times. 2005-01-07. Archived from the original on 2004-08-19. Retrieved 2014-01-06.

- ^ "Xi Jinping and the Chinese dream". The Economist. 2013-05-04. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 10 May 2016. Retrieved 2019-09-12.

- ^ Gil Hizi, "Speaking the China Dream: self-realization and nationalism in China’s public-speaking shows." Continuum 33.1 (2019): 37-50.

- ^ Peter Ferdinand, "Westward ho—the China dream and ‘one belt, one road’: Chinese foreign policy under Xi Jinping." International Affairs 92.4 (2016): 941-957, quoting p 955. DOI: 10.1111/1468-2346.12660

Further reading

- Befu, Harumi. Cultural Nationalism in East Asia: Representation and Identity (1993). Berkeley, Calif.: Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California.

- Cabestan, Jean-Pierre. "The many facets of Chinese nationalism." China perspectives (2005) 2005.59 online.

- Chang, Maria Hsia. Return of the Dragon: China's Wounded Nationalism, (Westview Press, 2001), 256 pp, ISBN 0-8133-3856-5

- Chow, Kai-Wing. "Narrating Nation, Race and National Culture: Imagining the Hanzu Identity in Modern China," in Chow Kai-Wing, Kevin M. Doak, and Poshek Fu, eds., Constructing nationhood in modern East Asia (2001). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp. 47–84.

- Gries, Peter Hays. China's New Nationalism: Pride, Politics, and Diplomacy, University of California Press (January, 2004), hardcover, 224 pages, ISBN 0-520-23297-6

- Dura, Prasenjit, "De-constructing the Chinese Nation," in Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs (July 1993, No. 30, pp. 1–26).

- Dura, Prasenjit. Rescuing History from the Nation Chicago und London: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

- Fitzgerald, John. Awakening China - Politics, Culture and Class in the Nationalist Revolution (1996). Stanford University Press.

- He, Baogang. Nationalism, national identity and democratization in China (Routledge, 2018).

- Hoston, Germaine A. The State, Identity, and the National Question in China and Japan (1994). Princeton UP.

- Hughes, Christopher. Chinese Nationalism in the Global Era (2006).

- Judge, Joan. "Talent, Virtue and Nation: Chinese Nationalism and Female Subjectivities in the Early Twentieth Century," American Historical Review 106#3 (2001) pp 765–803. online

- Karl, Rebecca E. Staging the World - Chinese Nationalism at the Turn of the Twentieth Century (Duke UP, 2002) excerpt

- Leibold, James. Reconfiguring Chinese nationalism: How the Qing frontier and its indigenes became Chinese (Palgrave MacMillan, 2007).

- Lust, John. "The Su-pao Case: An Episode in the Early Chinese Nationalist Movement," Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 27#2 (1964) pp 408–429. online

- Nyíri, Pál, and Joana Breidenbach, eds. China Inside Out: Contemporary Chinese Nationalism and Transnationalism (2005) online

- Pye, Lucian W. "How China's nationalism was Shanghaied." Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs 29 (1993): 107-133.

- Tan, Alexander C. and Boyu Chen."China's Competing and Co-opting Nationalisms: Implications to Sino-Japanese Relations." Pacific Focus (2013) 28#3 pp. 365–383). abstract

- Tønnesson, Stein. "Will nationalism drive conflict in Asia?." Nations and Nationalism 22#2 (2016) online.

- Unger, Jonathan, ed. Chinese nationalism (M, E. Sharpe, 1996).

- Wang, Gungwu. The revival of Chinese nationalism (IIAS, International Institute for Asian Studies, 1996).

- Wei, C.X. George and Xiaoyuan Liu, eds. Chinese Nationalism in Perspective: Historical and Recent Cases (2001) online

- Zhang, Huijie, Fan Hong, and Fuhua Huang. "Cultural Imperialism, Nationalism, and the Modernization of Physical Education and Sport in China, 1840–1949." International Journal of the History of Sport 35.1 (2018): 43-60.

- Zhao Suisheng. A Nation-State by Construction. Dynamics of Modern Chinese Nationalism (Stanford UP, 2004)

External links

- Harvard Asia Pacific Review, 2010. "Nations and Nationalism." Available at Issuu Harvard Asia Pacific Review 11.1 ISSN 1522-1113

- Chinese Nationalism and Its Future Prospects, Interview with Yingjie Guo (June 27, 2012)