Sri Lankan Moors

ලංකා යෝනක இலங்கைச் சோனகர் | |

|---|---|

20th century Sri Lankan Moors | |

| Total population | |

| 1,869,820[1] (9.2% of the Sri Lankan population; 2012)[2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Province | |

| 569,182 | |

| 450,505 | |

| 260,380 | |

| 252,694 | |

| Languages | |

| Languages of Sri Lanka: Tamil Some Sinhala and English | |

| Religion | |

| Islam (mostly Sunni) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

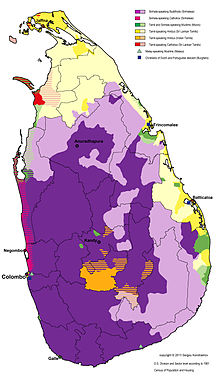

Sri Lankan Moors (Template:Lang-ta; Template:Lang-si; formerly Ceylon Moors; colloquially referred to as Muslims or Moors) are an ethnic minority group in Sri Lanka, comprising 9.2% of the country's total population.[1] They are mainly native speakers of the Tamil language with influence of Sinhalese and Arabic words.[3][4][5] They are predominantly followers of Islam.[6] The Sri Lankan Muslim community is divided as Sri Lankan Moors, Indian Moors and Sri Lankan Malays as per their history and traditions.[7]

The Moors trace their ancestry to Arab traders who first settled in Sri Lanka around the 9th century who intermarried with local women.[8][9][10][11] The concentration of Moors are the highest in the Ampara, Trincomalee and Batticaloa districts. Sri Lankan Muslims have both Tamil and Sinhalese converts, together with a minority who progeny of West Asian traders. [12][13]

Etymology

The Portuguese named the Muslims in India and Sri Lanka after the Muslim Moors they met in Iberia.[14] The word Moors did not exist in Sri Lanka before the arrival of the Portuguese colonists.[15] The term 'Moor' was chosen because of the Islamic faith of these people and was not a reflection of their origin.[16]

The Tamil term Sonakar along with the Sinhalese term Yonaka, has been thought to have been derived from the term Yona, a term originally applied to Greeks, but sometimes also Arabs and other west Asians.[17][18]

History

Origins theories

Some scholars hold the view that the Sri Lankan Moors are descended from the Marakkar, Mappilas, Memons, Lebbes, Rowthers and Pathans of South India.[19]

Sri Lankan Moor scholar Dr. Ameer Ali in his summary of the origin history of Sri Lankan Moors states the following:

'In actual fact, the Muslims of Sri Lanka are a mixture of Arab, Persian, Dravidian and Malay blood of which the Dravidian element, because of centuries of heavy Indian injection has remained the dominant one.'[20]

Another view suggests that the Arab traders, however, adopted the Sinhalese and Tamil languages only after settling in Sri Lanka.[11] This version claims that the features of Sri Lankan Moors are different from that of Tamils. The cultural practices of the Moors also vary significantly from the other communities on the island. Thus, most scholars classify the Sri Lankan Moors and Tamils as two distinct ethnic groups, who speak the same language.[11] This view is dominantly held by the Sinhalese favoring section of the Moors, as well as the Sri Lankan government, which lists the Moors as a separate ethnic community.[16]

Although the caste system is not observed by the Moors such as it is in the other ethnic groups in Sri Lanka, their kudi system (matriclan system) is an extension of the Tamil tradition.[21]

Medieval era

The Sri Lankan Moors along with Mukkuvar dominated once in medieval era the pearl trade in Sri Lanka.[22] Alliances and intermarriages between both communities were observed in this period.[23] They held close contact with other Muslims of Southern India through coastal trade.[24]

The Moors had their own court of justice for settling their disputes. Upon the arrival of the Portuguese colonizers in the 16th century, larger population of Moors were expelled from cities such as the capital city Colombo, which had been a Moor-dominated city at that time. The Moors were thus migrating towards east and were settled there through the invitation of the Kingdom of Kandy.[24] Robert Knox, a British sea captain of the 17th century, noted that the Kings of Kandy Kingdom built mosques for the Moors.[25]

Sri Lankan Civil War

The Sri Lankan Civil War was a 26-year conflict fought on the island of Sri Lanka between government and separatist militant organisation Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (the LTTE, also known as the Tamil Tigers). LTTE tried to make northern Sri Lanka into a Tamil country called Tamil Eelam.[26]

Since 1888 under the initiative of Ponnambalam Ramanathan, the Sri Lankan Tamils launched a campaign to classify those Sri Lankan Moors who spoke Tamil as Tamils, primarily to bolster their population numbers for the impending transition to democratic rule in Sri Lanka.[27] Their view holds that the Sri Lankan Moors were mainly Tamil converts to Islam. The claim that the Moors were the progeny of the original Arab settlers might hold good for a few families, but not for the entire bulk of the community.[16]

According to some Tamil nationalists, the concept of Arab descent among Tamil-speaking Moors was invented just to keep the community away from the Tamils, and this 'separate identity' intended to check the latter's demand for the separate state Tamil Eelam and to flare up hostilities between the two groups in the broader Tamil-Sinhalese conflict.[16][28][29]

The expulsion of the Muslims from the Northern province was an act of ethnic cleansing[30][31] carried out by the Tamil militant Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) organization in October 1990. In order to achieve their goal of creating a mono ethnic Tamil state[32][33] in the North Sri Lanka, the LTTE carried out riots and forcibly expelled the Muslim population from the Northern Province and confiscated their properties and destroyed the Mosques.[34]

The riots and expulsion by LTTE still carries bitter memories among Sri Lanka's Muslims. In 2002, the LTTE militant leader Vellupillai Prabhakaran formally apologized for the riots and expulsion of the Muslims from the North.[35][36] There has been a stream of Muslims travelling to and from Jaffna since the ceasefire. Some families have returned and the re-opened the Osmania College now has 60 students enrolled. Osmania College was once a prominent educational institution for the city's Muslim community.[37][38] According to a Jaffna Muslim source, there is a floating population of about 2,000 Muslims in Jaffna. Around 1,500 are Jaffna Muslims, while the rest are Muslim traders from other areas. About 10 Muslim shops are functioning and the numbers are slowly growing.[39]

Society

Demographics

| Census | Population | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 1881 | 184,500 | 6.69% |

| 1891 | 197,200 | 6.56% |

| 1901 | 228,000 | 6.39% |

| 1911 | 233,900 | 5.70% |

| 1921 | 251,900 | 5.60% |

| 1931 Estimate | 289,600 | 5.61% |

| 1953 | 464,000 | 5.73% |

| 1963 | 626,800 | 5.92% |

| 1971 | 855,724 | 6.74% |

| 1981 | 1,046,926 | 7.05% |

| 2011 | 1,892,638 | 9.2% |

Language

Sinhalese language is spoken by those Moors whose maternal lineage[citation needed] is Sinhalese and Tamil is the mother tongue of the community whose maternal lineage[citation needed] are Tamil, however depending on where they live in the country, they may also additionally speak Tamil, Sinhala and or English. According to the 2012 Census 58.7% or 862,397 Sri Lankan Moors also spoke Sinhala and 30.4% or 446,146 Sri Lankan Moors also spoke English.[40] Moorish Tamil bears the influence of Arabic.[6]

Sri Lankan Muslim Tamil

Tamil was a borrowed language used as a means of convenience by the descendants of the majority of Muslims in Sri Lanka, i.e., the Arab traders who settled in the island centuries ago.[41] In addition, there were also intermarriages that took place between them and locals during the time.[11] As a result, Tamil became the predominant language used by Muslims in Sri Lanka even though many refuse to accept it as their first language. Religious sermons are delivered in Tamil even in regions where Tamil is not the majority language. Islamic Tamil literature has a thousand-year heritage.[42]

The Tamil dialect spoken by Muslims in Sri Lanka is identified as Sri Lankan Muslim Tamil (SLMT). It is a social dialect of Sri Lankan Tamil that falls under the larger category of the colloquial variety of Tamil. SLMT has distinct phonological, morphological and lexical differences in comparison to other varieties of SLT since it is heavily influenced by the Arabic language.[41] Due to this, we can see the use of many Persian-Arabic loan words in SLMT vocabulary. This distinctiveness between SLMT and other spoken varieties of SLT brings out the different religious and cultural identities of the Tamil speaking ethnic groups.[41]

As an example, the SLT term for corpse is ‘caavu’ but the SLMT uses the Arabic term ‘mayyatu’. Another example is the verb ‘pray’ which is ‘vanaku’ in SLT and ‘tholu’ in SLMT. The kinship terms used by Muslims in the country are also different when compared with the SLT terms. Following are some terms that show the difference between SLMT and most varieties of SLT/Tamil.

| Kinship Term | SLT/Tamil | SLMT |

|---|---|---|

| Father | appa | vaapa |

| Mother | amma | umma |

| Brother | anna | naana/kaaka |

| Sister | akka | dhaatha |

| Son | makan | mavan |

| Daughter | makal | maval |

Interestingly, one can also notice ethno-regional variations in SLMT and categorize them into two major sub-dialects such as North-Eastern Muslim Tamil (NEMT) and Southern Muslim Tamil (SMT).[41] SMT is found in the Southern, Western and Central provinces with some variations and other linguistic features within it. As an example, Muslims in the Western province, especially in Colombo tend to code-mix their speech with Tamil and English terms.

On the other hand, NEMT is found in Northern and Eastern provinces. While NEMT is heavily influenced by the SLT that is spoken by the Tamil population in the regions, SMT is heavily influenced by the Arabic phonology. One phonological variation between these two sub-dialects is that SMT replaces the Tamil sound /sa/ with /sha/ because of the Arabic phonological influence.Another phonological variation is that SMT uses voiced plosives such as /b, d, j, g/ whereas NEMT uses voiceless plosives such as /v, p, t, c, k/ instead of them.[41]

| English Term | SMT | NEMT |

|---|---|---|

| Drain | gaan | kaan |

| Fear | bayam | payam |

| Money | shalli | salli |

| Sky | banam | vaanam |

| Item | Shaaman | saaman |

| Well | genar | kinar |

Another symbolic representation of the Southern variety is the shortening of Tamil verbs.[43] As an example, the verb ‘to come’ known as ‘varukhudu’ in SLT/NEMT would be shortened and pronounced as ‘varudu.’

Furthermore, the Moors like their counterparts in Tamil Nadu,[44][45] use the Arwi which is a written register of the Tamil language with the use of the Arabic alphabet.[46] The Arwi alphabet is unique to the Muslims of Tamil Nadu and Sri Lanka, hinting at erstwhile close relations between the Tamil Muslims across the two territories.[44]

However, SLMT is only a spoken variety that is limited to the domestic sphere of the community members. In addition, they frequently tend to code-switch and code-mix when they communicate with a non-Muslim or a fellow Muslim in a different region.

Culture

The Sri Lankan Moors have been strongly shaped by Islamic culture, with many customs and practices according to Islamic law. While preserving many of their ancestral customs, the Moors have also adopted several South Asian practices.[47]

The Moors practice several customs and beliefs, which they closely share with the Arab, Sri Lankan Tamils and Sinhalese People. Tamil and Sinhala customs such as wearing the Thaali or eating Kiribath were widely prevalent among the Moors. Arab customs such as congregational eating using a large shared plate called the 'sahn' and wearing of the North African fez during marriage ceremonies feed to the view that Moors are of mixed Sinhalese, Tamil and Arab heritage.[42][16]

There have been a growing trend amongst Moors to rediscover their Arab heritage and reinstating the Arab customs that are the norm amongst Arabs in Middle East and North Africa. These include replacing the sari and other traditional clothing associated with Sinhalese and Tamil culture in favour of the abaya and hijab by the women as well as increased interest in learning Arabic and appetite for Arab food by opening restaurants and takeaways that serve Arab food such as shawarma and Arab bread.

The late 19th century saw the phase of islamization of Sri Lankan Moors, primarily under the influence of M. C. Siddi Lebbe. He was a leading figure in the Islamic revival movement, and strengthened the Muslim identity of the Sri Lankan Moors.[48] He was responsible for the ideological framework for the Muslim ethnicity in Sri Lanka.[49]

See also

References

Citations

- ^ a b "A2 : Population by ethnic group according to districts, 2012". Census of Population & Housing, 2011. Department of Census & Statistics, Sri Lanka.

- ^ "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov.

- ^ Minahan, James B. (2012-08-30). Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-660-7.

- ^ Das, Sonia N. (2016-10-05). Linguistic Rivalries: Tamil Migrants and Anglo-Franco Conflicts. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-046179-9.

- ^ Richardson, John Martin (2005). Paradise Poisoned: Learning about Conflict, Terrorism, and Development from Sri Lanka's Civil Wars. International Center for Ethnic Studies. ISBN 9789555800945.

- ^ a b McGilvray, DB (November 1998). "Arabs, Moors and Muslims: Sri Lankan Muslim ethnicity in regional perspective". Contributions to Indian Sociology. 32 (2): 433–483. doi:10.1177/006996679803200213.

- ^ Nubin, Walter (2002). Sri Lanka: Current Issues and Historical Background. Nova Publishers. p. 147. ISBN 9781590335734.

- ^ De Silva 2014, p. 47.

- ^ Papiha, S.S.; Mastana, S.S.; Jaysekara, R. (October 1996). "Genetic Variation in Sri Lanka". Human Biology. 68 (5): 707–737 [709]. JSTOR 41465515.

- ^ de Munck, Victor (2005). "Islamic Orthodoxy and Sufism in Sri Lanka". Anthropos. 100 (2): 401–414 [403]. JSTOR 40466546.

- ^ a b c d Mahroof, M. M. M. (1995). "Spoken Tamil Dialects Of The Muslims Of Sri Lanka: Language As Identity-Classifier". Islamic Studies. 34 (4): 407–426 [408]. JSTOR 20836916.

- ^ https://theconversation.com/who-are-sri-lankas-muslims-115825

- ^ https://thefederal.com/the-eighth-column/why-tamil-speaking-muslims-in-sri-lanka-broke-away-from-tamil-identity/

- ^ Pieris, P.E. "Ceylon and the Hollanders 1658-1796". American Ceylon Mission Press, Tellippalai Ceylon 1918

- ^ Ross Brann, "The Moors?", Andalusia, New York University. Quote: "Andalusi Arabic sources, as opposed to later Mudéjar and Morisco sources in Aljamiado and medieval Spanish texts, neither refer to individuals as Moors nor recognize any such group, community or culture."

- ^ a b c d e Mohan, Vasundhara (1987). Identity Crisis of Sri Lankan Muslims. Delhi: Mittal Publications. pp. 9–14, 27–30, 67–74, 113–118.

- ^ Fazal, Tanweer (2013-10-18). Minority Nationalisms in South Asia. Routledge. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-317-96647-0.

- ^ Singh, Nagendra Kr; Khan, Abdul Mabud (2001). Encyclopaedia of the World Muslims: Tribes, Castes and Communities. Global Vision. ISBN 9788187746102.

- ^ Holt, John (2011-04-13). The Sri Lanka Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press. p. 429. ISBN 978-0-8223-4982-2.

- ^ Ali, Ameer (1997). "The Muslim Factor in Sri Lankan Ethnic Crisis". Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs. 17 (2). Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs Vol. 17, No. 2: 253–267. doi:10.1080/13602009708716375.

- ^ Klem, Bart (2011). "Islam, Politics and Violence in Eastern Sri Lanka" (PDF). The Journal of Asian Studies. 70 (3). The Journal of Asian Studies Vol. 70, No. 3: 737. doi:10.1017/S002191181100088X. JSTOR 41302391.

- ^ Hussein, Asiff (2007). Sarandib: an ethnological study of the Muslims of Sri Lanka. Asiff Hussein. p. 330. ISBN 9789559726227.

- ^ McGilvray, Dennis B. (2008-04-16). Crucible of Conflict: Tamil and Muslim Society on the East Coast of Sri Lanka. Duke University Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-8223-8918-7.

- ^ a b MAHROOF, M.M.M. (1990). "Impact of European-Christian Rule on the Muslims of Sri Lanka: A Socio-Historical Analysis". Islamic Studies. 29 (4). Islamic Research Institute, International Islamic University, Islamabad: Islamic Studies, Vol. 29, No. 4: 354, 356. JSTOR 20840011.

- ^ MAHROOF, M.M.M. (1991). "Mendicants and Troubadours: Towards a Historical Taxonomy of the Faqirs of Sri Lanka". Islamic Studies. 30 (4). Islamic Research Institute, International Islamic University, Islamabad: Islamic Studies, Vol. 30, No. 4: 502. JSTOR 20840055.

- ^ "Sri Lanka – Living With Terror". Frontline. PBS. May 2002. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ "A Criticism of Mr Ramanathan's "Ethnology of the Moors of Ceylon" – Sri Lanka Muslims". Sri Lanka Muslims. 2017-04-21. Retrieved 2017-11-24.

- ^ Zemzem, Akbar (1970). The Life and Times of Marhoom Wappichi Marikar (booklet). Colombo.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Analysis: Tamil-Muslim divide". BBC News World Edition. 2002-06-27. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2011-11-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Sri Lanka's Muslims: out in the cold". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 2007-07-31.

- ^ http://www.theacademic.org/feature/162395480028024/index.shtml. Retrieved 2011-11-20.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)[dead link] - ^ "Ethnic cleansing: Colombo". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 2007-04-13.

- ^ The “liberation” of the east heightens the anxieties of the Muslim community about its role in the new scheme of things. Archived 2009-08-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ SUBRAMANIAN, T.S. (May 10, 2002). "Prabakaran in First Person". Frontline.

- ^ "Hon. V. Prabhakaran : Press Conference at Killinochi 2002". EelamView. Archived from the original on 2016-04-06.

- ^ Palakidnar, Ananth (15 February 2009). "Mass resettlement of Muslims in Jaffna". Sunday Observer. Archived from the original on 12 March 2011.

- ^ Holmes, Walter Robert (1980), Jaffna, Sri Lanka, Christian Institute for the Study of Religion and Society of Jaffna College, p. 190

- ^ Hindu On Net. "A timely and prudent step by the LTTE". Archived from the original on 2004-12-07. Retrieved 2006-04-30.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing 2011". www.statistics.gov.lk. Department of Census and Statistics. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Nuhman, M. A (2007). Sri Lankan Muslims – Ethnic Identity within Cultural Diversity. http://www.noolaham.org/wiki/index.php/Sri_Lankan_Muslims_-_Ethnic_Identity_within_Cultural_Diversity: International Centre for Ethnic Studies. pp. 71–79. ISBN 978-955-580-109-6.

{{cite book}}: External link in|location= - ^ a b "Sri Lankan Muslims Are Low Caste Tamil Hindu Converts Not Arab Descendants". Colombo Telegraph. 2013-05-06. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- ^ Davis, Christina. (2018). Muslims in Sri Lankan language politics: A study of Tamil- and English-medium Education. International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 2018. 125-147. 10.1515/ijsl-2018-0026.

- ^ a b Torsten Tschacher (2001). Islam in Tamilnadu: Varia. (Südasienwissenschaftliche Arbeitsblätter 2.) Halle: Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg. ISBN 3-86010-627-9. (Online versions available on the websites of the university libraries at Heidelberg and Halle: http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/savifadok/volltexte/2009/1087/pdf/Tschacher.pdf and http://www.suedasien.uni-halle.de/SAWA/Tschacher.pdf).

- ^ 216 th year commemoration today: Remembering His Holiness Bukhary Thangal Sunday Observer – January 5, 2003. Online version Archived 2012-10-02 at the Wayback Machine accessed on 2009-08-14

- ^ R. Cheran, Darshan Ambalavanar, Chelva Kanaganayakam (1997) History and Imagination: Tamil Culture in the Global Context. 216 pages, ISBN 978-1-894770-36-1

- ^ McGilvray, D.B (1998). "Arabs, Moors and Muslims: Sri Lankan Muslim ethnicity in regional perspective". Contributions to Indian Sociology. 32 (2): 433–483. doi:10.1177/006996679803200213.

- ^ Holt, John Clifford (2016-09-30). Buddhist Extremists and Muslim Minorities: Religious Conflict in Contemporary Sri Lanka. Oxford University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-19-062439-2.

- ^ Nuk̲amān̲, Em Ē; Program, ICES Sri Lanka; Studies, International Centre for Ethnic (2007). Sri Lankan Muslims: ethnic identity within cultural diversity. International Centre for Ethnic Studies. p. 104. ISBN 9789555801096.

Bibliography

- De Silva, K. M. (2014). A history of Sri Lanka ([Revised.] ed.). Colombo: Vijitha Yapa Publications. ISBN 978-955-8095-92-8.

Further reading

- Victor C. de Munck. Experiencing History Small: An analysis of political, economic and social change in a Sri Lankan village. History & Mathematics: Historical Dynamics and Development of Complex Societies. Edited by Peter Turchin, Leonid Grinin, Andrey Korotayev, and Victor C. de Munck, pp. 154–169. Moscow: KomKniga, 2006. ISBN 5-484-01002-0