MV Britannic (1929)

Britannic

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Operator |

|

| Port of registry | Liverpool |

| Route | |

| Ordered | 1927 |

| Builder | Harland and Wolff, Belfast |

| Yard number | 807 |

| Laid down | 14 April 1927 |

| Launched | 6 August 1929 |

| Maiden voyage | 28 June 1930 |

| Refit | 1947 |

| Identification |

|

| Fate | Scrapped 1960 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Ocean liner |

| Tonnage | |

| Length | 683.6 ft (208.4 m) |

| Beam | 82.4 ft (25.1 m) |

| Draught | 35 ft (11 m) |

| Depth | 48.6 ft (14.8 m) |

| Installed power | 4,214 NHP |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 17.5 knots (32.4 km/h) |

| Capacity |

|

| Sensors and processing systems |

|

| Armament |

|

| Notes | Running mate: Georgic |

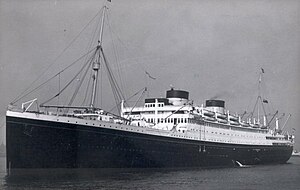

MV Britannic was a British transatlantic ocean liner that was launched in 1929 and scrapped in 1960. She was the penultimate ship built for White Star Line before its 1934 merger with Cunard Line. When built, Britannic was the largest motor ship in the UK Merchant Navy. Her running mate ship was the MV Georgic.

In 1934 White Star merged with Cunard Line, however both Britannic and Georgic retained their White Star Line colours and flew the house flags of both companies.

From 1935 the pair served London, and at the time they were the largest ships to do so. From early in her career Britannic operated on cruises as well as scheduled transatlantic services. Diesel propulsion, economical speeds and modern "cabin ship" passenger facilities enabled Britannic and Georgic to make a profit throughout the 1930s, when many other liners were unable to do so.

In the Second World War Britannic was a troop ship. In 1947 she was overhauled, re-fitted, modernised and returned to civilian service. She outlived her sister Georgic and became the last White Star liner still in commercial service. Britannic was scrapped in 1960 after three decades of service.

She was the last of three White Star Line ships called Britannic. The first Britannic was a steamship launched in 1874 and scrapped in 1903. The second was launched in 1914, completed as the hospital ship HMHS Britannic and sunk by a mine in 1916.

Background

On 1 January 1927 the International Mercantile Marine Company sold White Star Line to the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company (RMSP). At the time White Star had one new steamship on order, Laurentic, and was discussing designs with Harland and Wolff for a proposed 1,000-foot liner, but overall the White Star fleet needed modernising.[1]

Motor ships were more economical than steam, and in the 1920s the maximum size of marine diesel engine had increased rapidly. RMSP had recently taken delivery of two large motor ships, Asturias (1925) and Alcantara (1926), and chose diesel to replace White Star's Template:Sclass-. The replacements were to be smaller than the Big Four but more luxurious.[2]

Building

On 14 April 1927 Harland and Wolff laid Britannic's keel[3] on slip number one in its Belfast yard.[4] She was launched on 6 August 1929, started three days of sea trials in the Firth of Clyde on 25 or 26 May 1930,[3][4] and was completed on 21 June 1930.[5]

Britannic had two screws, each driven by a five-cylinder four-stroke double-acting diesel engine. Between them the two engines developed 4,214 NHP[6] and gave Britannic a speed of 17.5 knots (32.4 km/h).[7] When new, she was the largest motor ship in the UK Merchant Navy[8] and the second-largest in the World, second only to the Italian liner Augustus.[9][10]

Britannic was built as a "cabin ship" with berths for 1,553 passengers: 504 cabin class, 551 tourist class and 498 third class.[11] She had a gymnasium, a swimming pool, and her cabin class dining saloon was in Louis XIV style.[12] She had eight holds, one of which could carry unpackaged cars. Two holds were refrigerated,[11] and her total refrigerated capacity was 72,440 cu ft (2,051 m3).[13]

12 bulkheads divided her hull into watertight compartments. Their watertight doors could be closed either electrically from her bridge, or manually.[11] She had 24 lifeboats, two motor boats and two backup boats.[14]

Britannic had two funnels. As on many early Harland and Wolff motor ships they were low and broad.[10] Only her aft funnel was a diesel exhaust. Her forward funnel was a dummy that housed two smoking rooms:[15] one for her deck officers and the other for the engineer officers.[12] It also contained water tanks, and, later in her career, radar equipment.[16]

Britannic was painted in White Star Line colours:[10] black hull with a gold line, white superstructure and ventilators, red boot-topping,[17] and buff funnels with a black top. She and Georgic kept their White Star colours after White Star merged with Cunard in 1934.[18]

White Star years

In 1930 Britannic was delivered from Belfast to Liverpool amid enthusiastic press coverage. When she left Liverpool on 28 June to begin her maiden voyage an estimated 14,000 people turned out[19] and gave her what was reported to be the "greatest send-off known to Merseyside". She called at Belfast and Glasgow to load mail, and then continued to New York.[20]

On 8 July Britannic entered New York harbour, dressed overall.[12] Over the next few days, 1,500 people paid $1 each to go aboard her while she was in port,[21] and on 12 July a crowd of more than 6,000 came to see her leave New York for Cobh and Liverpool.[22]

For her first three trips Britannic's speed was limited to 16 knots (30 km/h) until her engines were run in.[23] Thereafter her speed was increased, and at the beginning of October 1930 she averaged 17+3⁄4 knots (32.9 km/h) on a westbound crossing.[24] On an eastbound crossing in July 1932 she averaged 19+1⁄4 knots (35.7 km/h), beating her own record.[25]

By the time Britannic entered service, the Great Depression had caused a global slump in merchant shipping. Several White Star Line steamships operated cruises for at least part of the year to make up for the fall in transatlantic passenger numbers. But Britannic's lower running costs enabled her to make a profit on the route.[26] In 1931 White Star Line operated ten ships, but only four made a profit on scheduled routes. Britannic being the most profitable by far.[27]

Between some scheduled transatlantic crossings Britannic fitted in short cruises from New York. White Star Line offered four-day weekend and midweek cruises. In 1931 the tourist class fare for these on Britannic was $35.[28] She also attracted charter trade, such as a 16-day cruise to the West Indies in February and March 1932 to raise funds for the Frontier Nursing Service.[29][30]

In summer Britannic shared the route with the older RMS Adriatic, Baltic and Cedric.[31] In 1932 her sister ship Georgic was completed[32] and joined her on the route.[27]

In her first 15 months in service Britannic averaged only 609 passengers per voyage, which was less than 40 percent of her capacity.[33] And two cruises from New York to the Mediterranean that she was due to make in spring 1932 were cancelled for lack of enough bookings.[34]

By 1932 bookings for cabin class was still slack, but demand for Britannic's tourist class exceeded the number of berths available. On a sailing on Britannic from New York on 4 June that year White Star allocated cabin class berths to a number of tourist class passengers to meet demand.[35]

In May 1932 White Star Line organised a fashion show of travel clothes aboard Britannic when she was in port in New York[36] in a bid to earn extra income.

In 1933 the largest number of passengers on Britannic on a single crossing was 1,003, which was less than 65 percent of her capacity. But it was the highest number of any transatlantic liner that year.[10][37] Britannic's luxury and well-appointed public saloons attracted enough passengers for her to pay her way when other ships did not.[15]

On 15 December 1933 Britannic ran aground on a mud flat off Governors Island in Boston Harbour. She was undamaged and refloated the next day with the aid of six tugboats.[38]

Cunard White Star Line

On 20 July 1931 the Royal Mail Case opened at the Old Bailey, which led to the collapse of White Star Line's parent company.[39] On 1 January 1934 White Star Line merged with Cunard, with the latter holding 62 percent of the capital.[40] By 1936 the resulting Cunard-White Star Line sold most of the former White Star fleet except Britannic, Georgic and Laurentic.[41]

In April 1935 Britannic and Georgic were transferred to the route between London and New York via Le Havre, Southampton and Cobh.[42][43] This made them the largest ships to visit London.[44]

In June 1935 Britannic's Master, Captain William Hawkes, RD, ADC, RNR, was made a CBE.[45][46] On 22 July two passengers got married aboard Britannic just before she sailed on a cruise to Bermuda. Captain Hawkes did not conduct the ceremony, but he did give the bride away.[47]

On 4 January 1937 Britannic suffered slight engine trouble on arrival in New York. She was held at Ellis Island for 45 minutes for temporary repairs before proceeding to dock.[48]

In October 1937 the BBC experimented with a television receiver in one of the state rooms on Britannic's A deck. After she left London on 29 October, BBC technicians tested the reception of "telephotograms" transmitted from the Alexandra Palace television station in London as Britannic voyaged away from the capital and down the English Channel. The experiment continued for 24 hours, until Britannic was 30 nautical miles (56 km) south of Hastings. The receiver's screen was 10 by 12 inches (250 by 300 mm). Britannic's Master, Captain AT Brown, watched the experiment and said that both the picture and the sound were clear.[49]

Britannic and Georgic faced modern competition from United States Lines' Manhattan and Washington and CGT's Champlain and Lafayette (fr). In 1937 Britannic carried 26,943 passengers, Georgic carried a few hundred more, but Champlain carried more than either of them.[50]

In 1938 Britannic carried 1,170 passengers on one eastbound crossing in June, which was 75 percent of her capacity.[51] However, on a westbound crossing in October she carried only 729 passengers.[52]

Second World War

On 27 August 1939, a few days before the Second World War began, Britannic was requisitioned as she was returning from New York. She was converted into a troop ship at Southampton. A few days later left she embarked British Indian Army officers and naval officers,[53] whom she then took from Greenock to Bombay.[54] While in Bombay[53] she was fitted with one BL 6-inch Mk XII naval gun for defence against surface craft and one QF 3-inch 20 cwt high-angle gun for anti-aircraft defence[55] to make her a defensively equipped merchant ship.

Britannic loaded cargo, returned to England and then returned to commercial service[53] between Liverpool and New York.[56] By January 1940 her superstructure had been repainted from white to buff, and a pillbox had been built on each wing of her bridge as protection for the deck officer on watch.[55]

By January 1940, UK passenger ships including Britannic displayed posters warning passengers "BEWARE. Above all, never give away the movements of His Majesty's ships." Crews were warned that disclosing information such as ship movements violated the Defence of the Realm Act 1914.[57]

But in the USA, which remained neutral until December 1941, newspapers continued to publish the arrival and departure of every Allied passenger liner.[58] In April 1940 The New York Times even published how many UK Merchant Navy seafarers arrived on Britannic and the Cunard liner RMS Cameronia to join which cargo ships, and even gave some idea where those cargo ships were.[57]

On 20 February 1940 an anonymous telephone call to the New York City Police Department warned that a bomb would be planted aboard Britannic. NYPD officers searched the ship but found nothing.[59]

Britannic's westbound crossings carried many refugees from central Europe,[60] including Germans fleeing Nazism.[55][57] She also carried many UK children sent to North America[60][61] by the Children's Overseas Reception Board. The overseas evacuation of children was terminated after a U-boat sank the Ellerman Lines ship City of Benares in September 1940, killing 77 children.

In January 1940 the pianist Harriet Cohen travelled on Britannic to begin a concert tour of the USA.[55] On the same voyage Britannic also carried eight racehorses that had been sold to US buyers. Five of the horses had belonged to the Aga Khan. Louis B. Mayer bought four of the horses, Charles S. Howard bought two, and Neil S. McCarthy and a Gordon Douglas of Wall Street each bought one.[55]

In June 1940 Britannic's westbound passengers included the Earl and Countess of Athlone, who disembarked at Halifax, Nova Scotia as the Earl had just been appointed Governor General of Canada. On the same voyage Jan Masaryk, who had been Czechoslovak ambassador to the UK and was about to become Foreign Minister of the Czechoslovak government-in-exile, travelled to New York.[60]

On an eastbound voyage in summer 1940 Britannic carried "hundreds" of obsolescent French 75mm field guns to the UK, to reinforce defence against the threat of German invasion. One of her officers later recalled that they were stowed on her promenade deck.[62]

In July Britannic's took Noël Coward to New York. He said the UK Minister of Information, Duff Cooper, had sent him to meet Lord Halifax, the UK ambassador in Washington.[61] In fact he was working for the UK Secret Intelligence Service to influence public opinion in the then-neutral USA to support the Allied war effort.

Troop ship

On 23 August 1940 Britannic was requisitioned again. She sailed via South Africa to Suez and back, then to Suez again in 1941, and thence to Bombay again and back via Cape Town to the Firth of Clyde, where she arrived on 5 May. She then made one round trip to New York via Halifax before leaving the Clyde on 2 August for Bombay and Colombo via South Africa. Her return voyage was via Cape Town and Trinidad, arriving in Livepool on 29 November 1941.[56]

In 1942 Britannic made two more round trips between Britain and Bombay via South Africa. From November 1942 she made two round trips between Britain and South Africa.[56] Her capacity was increased from 3,000 to 5,000 troops.[63] In June 1943 she took troops to Algiers in Convoy KMF 17, and then went via Gibraltar and South Africa to Bombay, arriving on 10 September. From Bombay she sailed through the Suez Canal to Augusta, Sicily, and then returned to Liverpool, where she arrived on 5 November 1943.[56]

Between November 1943 and May 1944 Britannic four transatlantic round trips: two to New York and two to Boston. She then took 3,288 troops with Convoy KMF 32 from Liverpool to Port Said in Egypt. She made two round trips between there and Taranto in Italy and then took 2,940 troops to Liverpool, where she arrived on 11 August.[56]

In November and December 1944 Britannic made one round trip to New York. In January 1945 she made a round trip to Naples and back, calling at Algiers on her return. From March to June she made two transatlantic round trips from Liverpool to Halifax and back, carrying Canadian servicemen's British brides and children.[64] In June and July she sailed from Liverpool to Port Said and back. In July and August she sailed to Quebec and back. In September and October she sailed from Liverpool via the Suez Canal to Bombay and back. In December 1945 she wailed to Naples.[56] Since the start of the war Britannic had carried 173,550 people,[10] including 20,000 US troops across the Atlantic in preparation for the Normandy landings,[54] and sailed 324,792 nautical miles (601,515 km).[64]

Post-war service

After the war the Ministry of War Transport and its successor the Ministry of Transport held Britannic in reserve until March 1947. Cunard White Star then had her overhauled and re-fitted at Harland and Wolff's yard at Bootle in Liverpool.[10][65][66] Her re-fit cost £1 million, and was slowed by post-war shortages of wood and other materials.[67]

Her passenger accommodation was simplified from three classes to two, and total capacity was reduced from 1,553 to 1,049. She now had 551 cabin class and 498 tourist class berths. Her décor was modernised in post-war Art Deco style. Modern fire detection systems were installed.[68] A significant number of the cabins were equipped with bathrooms and all had hot and cold running water.[69] Her state rooms in both classes were enlarged.[54] On A deck she had two state room suites each with bedroom, living room and bathroom.[69] The refit resulted in a slight increase of her tonnage to 27,666 GRT.[7]

Britannic began her first post-war commercial trip from Liverpool on 22 May 1948 to New York via Cobh.[70][71] As she entered New York harbour, two New York City fireboats accompanied her and gave a traditional display with their water jets.[62]

On that first westbound voyage Britannic carried 848 passengers,[72] which meant that her refurbished passenger accommodation was more than 80 percent full. On an eastbound voyage six weeks later she carried 971 passengers, meaning that more than 92 percent of her berths were taken.[73] Even one some winter crossings Britannic had plenty of passengers. On a westbound crossing in January 1949 she carried 801,[74] an occupancy rate of more than 76 percent.

On 4 July 1949 Britannic rescued two Estonian refugees in mid-Atlantic. They had built a 33-foot (10 m) sailing yacht called Felicitas, begun their voyage from the Baltic coast of the Soviet occupation zone of Germany, followed the coast of Europe to northern Spain, and then tried to cross the Atlantic to Canada. On 1 July Felicitas' auxiliary motor had failed, and at some point her mast had been broken by heavy seas. On 4 July Felicitas was about 750 nautical miles (1,390 km) west of Ireland when her crew sighted Britannic and attracted her attention by firing distress flares. Her Master said that about an hour after the rescue fog closed in, in which Felicitas and Britannic would have been unable to see each other.[75]

In November 1949 Britannic lost one of her anchors in bad weather in the River Mersey. Her departure was delayed for her spare anchor to be fitted.[76]

Cunard Line

In 1949 Cunard bought out White Star's share of the business, and at the end of the year discontinued the White Star name, but Britannic and Georgic continued to fly both house flags.[17]

On 1 June 1950 Britannic and United States Lines' cargo ship Pioneer Land collided head-on in thick fog near the Ambrose Lightship. Pioneer Land's bow was damaged but she reached New York unaided. Britannic sustained only minor damage and continued her voyage to Europe.[77][78]

In May 1952 Britannic took a US women's golf team to Britain to play in the Curtis Cup at Muirfield.[79]

In Liverpool on 20 November 1953 Britannic suffered a small leak from what was at first described as a fractured collar on her seawater intake.[80] The next day the problem was described as a fractured injection pipe in her sanitary pump. Her sailing was delayed for 24 hours for repairs.[81]

In January 1955 Cunard withdrew Georgic from service, leaving Britannic as the last former White Star liner in service.[64]

In 1953 and 1955 Britannic suffered fires, both of which were safely extinguished. The 1955 fire was in her number four hold on an eastbound voyage in April. 560 bags of mail, 211 items of luggage and four cars were destroyed, partly by the fire and partly by water used to extinguish the fire.[82][83]

In December 1956 Cunard announced that from January 1957 it would transfer Britannic to the route between Liverpool and Halifax via Cobh, due to increased passenger demand and increased migration to Canada.[84]

In July 1959 Cunard dismissed Britannic's Master, Captain James Armstrong. He was only months away from being promoted to command RMS Queen Mary. His trade union, the Mercantile Marine Service Association, said it was preparing legal action against Cunard. Armstrong said Cunard had given him the choice of resignation or dismissal. Both sides refused to reveal why he had been dismissed.[85]

Cruises

Transatlantic passenger traffic was seasonal. In the 1950s, as in the 1930s, operators of passenger liners used on seasonal cruises to try to keep their ships fully occupied through the year.

On 28 January 1950 Britannic left New York on a 54-day cruise from New York to Madeira and the Mediterranean. Tickets ranged from $1,350 to $4,500 per person.[86] Shortly after departure, only 80 nautical miles (150 km) east of the Ambrose Lightship, she suffered engine trouble and turned back for two days of repairs. Her passengers seemed not to mind the two-day extension of their vacation,[87] and a long winter cruise from New York became a regular part of Britannic's annual schedule.

By February 1952 Britannic's winter cruise was a 66-day tour to the Mediterranean.[88] On that occasion she carried only 459 passengers, which was less than 44 percent of her capacity, but it was enough for Cunard to repeat the cruise each year. Britannic's 1953 Mediterranean winter cruise was 65 days. Tickets started at $1,275, which was less than in 1950.[89]

Fares for Britannic's 66-day Mediterranean cruise in January 1956 also started at $1,275,[90] the same as in 1953, but she sailed with only 490 passengers,[91] making her slightly less than half-full. The cruise was to include a visit to Cyprus in February, but this was cancelled due to the state of emergency as Greek Cypriot separatists fought against British rule.[92]

Cunard planned a similar 66-day cruise for January 1957.[93] But in December 1956 it cancelled the cruise and said Britannic would remain on the transatlantic service for those two months, due to "The unsettled situation in the Mideast".[94] Cyprus was still under a state of emergency, Israel, the UK and France had invaded Egypt in October and November 1956, and the region remained tense.

In 1960 Britannic made her annual 66-day cruise from New York to the Mediterranean as usual.[95] Cunard had scheduled Britannic for 19 transatlantic crossings in 1961. But on 9 May 1960 the crankshaft in one of her main engines cracked, forcing her to stay in New York for repairs until July.[96] These took two months, cost about $400,000 and caused her to miss three voyages.[97] She returned to service,[98] but on 15 August Cunard announced that Britannic would be withdrawn from service in December 1960.[4][10]

Final voyages

In November 1960 Cunard announced that it would transfer RMS Sylvania to its New York route to replace Britannic.[99] On 25 November Britannic began her final eastbound crossing from New York via Cobh to Liverpool. Cunard marketed the voyage to Irish Americans wanting to spend Christmas in Ireland.[100] She was due to reach Liverpool on 3 December.[101]

Britannic left Liverpool on 16 December 1960 and reached Inverkeithing on the Firth of Forth[102] on 19 December to be scrapped. Thos W Ward Ltd[5] began to break her up in February 1961.[4]

Many of Britannic's interior fittings were auctioned.[4] Britannic's bell is now an exhibit in Merseyside Maritime Museum, Liverpool.

References

- ^ Wilson 1956, p. 48.

- ^ de Kerbrech 2009, p. 223.

- ^ a b de Kerbrech 2002, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d e "Britannic". Harland and Wolff. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ a b "Britannic". Shipping and Shipbuilding. Tees-built Ships. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Steamers & Motorships". Lloyd's Register (PDF). Vol. II. London: Lloyd's Register. 1931. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ a b Harnack 1949, p. 461.

- ^ Talbot-Booth 1936, p. 332.

- ^ Haws 1990, p. 101.

- ^ a b c d e f g Morrow, Edward A (21 August 1960). "Britannic to end long sea career". The New York Times. p. 86. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ a b c de Kerbrech 2002, p. 12.

- ^ a b c "Harbor welcomes the new Britannic". The New York Times. 8 July 1930. p. 46. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "List of Vessels Fitted with Refrigerating Appliances". Lloyd's Register (PDF). Vol. I. London: Lloyd's Register. 1931. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ de Kerbrech 2009, p. 224.

- ^ a b Wilson 1956, p. 51.

- ^ de Kerbrech 2002, p. 15.

- ^ a b Haws 1990, p. 24.

- ^ Talbot-Booth 1936, p. 441.

- ^ de Kerbrech 2002, pp. 14–15.

- ^ "Britannic due Monday". The New York Times. 1 July 1930. p. 58. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Finds public eager to see new liners". The New York Times. 13 July 1930. p. 32. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "6,000 see Britannic sail for Liverpool". The New York Times. 13 July 1930. p. 22. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Britannic not pressed". The New York Times. 10 July 1930. p. 50. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Britannic gains in speed". The New York Times. 6 October 1930. p. 33. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Britannic's fastest trip". The New York Times. 25 July 1932. p. 31. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ Anderson 1964, p. 172.

- ^ a b de Kerbrech 2002, p. 19.

- ^ "Britannic to have tourist space". The New York Times. 10 August 1931. p. 33. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Cruise to aid nursing fund". The New York Times. 8 December 1931. p. 3. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Society leaders join Caribbean cruise". The New York Times. 26 February 1932. p. 16. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ de Kerbrech 2009, pp. 225–226.

- ^ de Kerbrech 2009, p. 231.

- ^ "Britannic here on 33rd crossing". The New York Times. 20 October 1931. p. 52. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Britannic here a day late". The New York Times. 22 December 1931. p. 47. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Atlantic ship lines report fair trade". The New York Times. 6 June 1932. p. 33. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Ship to give fashion show". The New York Times. 2 May 1932. p. 35. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ de Kerbrech 2002, p. 20.

- ^ "Liner Britannic refloated". The New York Times. 17 December 1933. p. 39. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ Anderson 1964, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Wilson 1956, p. 59.

- ^ Anderson 1964, p. 216.

- ^ Wilson 1956, p. 60.

- ^ "Britannic here late". The New York Times. 22 July 1935. p. 31. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ Talbot-Booth 1936, p. 333.

- ^ "No. 15180". The Edinburgh Gazette. 7 June 1935. p. 491.

- ^ "Captain is decorated". The New York Times. 24 June 1935. p. 35. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Dora Edwards weds on liner Britannic". The New York Times. 23 July 1935. p. 23. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Britannic arrives with lame engine". The New York Times. 4 January 1937. p. 33. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Television tested on a liner at sea". The New York Times. 8 November 1937. p. 37. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ de Kerbrech 2002, pp. 28–29.

- ^ "4,230 sail on four liners". The New York Times. 12 June 1937. p. 35. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Britannic brings 729". The New York Times. 24 October 1937. p. 35. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ a b c de Kerbrech 2002, p. 31.

- ^ a b c "Liner Britannic due here Monday". The New York Times. 25 May 1948. p. 55. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Britannic arrives on 2d war voyage". The New York Times. 11 January 1940. p. 9. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Hague, Arnold. "Ship Movements". Port Arrivals / Departures. Don Kindell, Convoyweb. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ a b c "'Hush hush' signs on arriving liners". The New York Times. 2 April 1940. p. 15. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Britannic in dock today". The New York Times. 1 April 1940. p. 16. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Bomb tip causes extra guard on ship". The New York Times. 21 February 1940. p. 4. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ a b c "Britannic, Athlone's ship, here with 760, including Jan Masaryk". The New York Times. 22 June 1940. p. 17. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ a b "Two liners bring 372 children". The New York Times. 30 July 1940. p. 3. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ a b "Britannic returns as a 'new' vessel". The New York Times. 1 June 1948. p. 46. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ Haws 1990, p. 102.

- ^ a b c de Kerbrech 2002, p. 227.

- ^ Wilson 1956, p. 76.

- ^ de Kerbrech 2002, pp. 41–42.

- ^ "Britannic to sail soon". The New York Times. 24 October 1947. p. 44. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ de Kerbrech 2002, p. 46.

- ^ a b de Kerbrech 2002, p. 21.

- ^ de Kerbrech 2002, p. 42.

- ^ "Britannic to resume passenger service". The New York Times. 3 May 1948. p. 43. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Fog keeps Britannic from entering harbor". The New York Times. 31 May 1948. p. 29. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Britannic sails with 971". The New York Times. 2 July 1948. p. 41. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "810 here on Britannic". The New York Times. 31 January 1949. p. 35. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Liner here with 2 who fled Germany". The New York Times. 10 July 1949. p. 14. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Britannic sailing late". The New York Times. 22 November 1949. p. 59. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Liner, freighter collide off Ambrose as shifting fog slows air, ship traffic". The New York Times. 2 June 1950. p. 32. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ Eaton & Haas 1989, p. 247.

- ^ "Curtis Cup squad off for England". The New York Times. 22 May 1952. p. 37. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Britannic develops leak". The New York Times. 21 November 1953. p. 29. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Britannic repairs speeded". The New York Times. 22 November 1953. p. 239. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Mid-Atlantic fire in Britannic's hold destroys luggage, mail and four autos". The New York Times. 29 April 1955. p. 47. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Liner fire investigated". The New York Times. 30 April 1955. p. 35. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Britannic to go on Canada run". The New York Times. 22 December 1956. p. 2. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Britannic's Captain dismissed; passenger complaints hinted". The New York Times. 25 August 1959. p. 63. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Britannic is scheduled for long winter cruise". The New York Times. 17 July 1949. p. 151. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Britannic's cruise 'extended' 2 days". The New York Times. 30 January 1950. p. 25. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Britannic is delayed three hours in bay to send injured passenger to city hospital". The New York Times. 2 February 1952. p. 30. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Britannic to cruise again". The New York Times. 17 June 1952. p. 55. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Britannic cruise set". The New York Times. 13 June 1955. p. 43. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Britannic sails on cruise". The New York Times. 27 January 1956. p. 48. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Cunarder drops Cyprus visit". The New York Times. 11 February 1956. p. 25. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Winter cruise for Britannic". The New York Times. 21 May 1956. p. 26. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Cunard cancels cruise". The New York Times. 17 December 1956. p. 42. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ de Kerbrech 2002, p. 229.

- ^ "Britannic trip canceled". The New York Times. 10 May 1960. p. 74. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Costly stay for Britannic". The New York Times. 8 July 1960. p. 48. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "50 young tourists wait table aboard struck liner Britannic". The New York Times. 29 August 1960. p. 27. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Britannic's farewell". The New York Times. 21 November 1960. p. 58. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ Morrow, Edward A (13 November 1960). "Cruise to Ireland will make the Britannic only a memory". The New York Times. p. 368. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ Bamberger, Werner (25 November 1960). "Seaman recalls years with ship". The New York Times. p. 27. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ de Kerbrech 2002, p. 62.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Roy Claude (1964). White Star. Liverpool: T Stephenson & Sons Ltd. OCLC 3134809.

- de Kerbrech, Richard (2002). The Last Liners of the White Star Line: MV Britannic and MV Georgic. Shipping Book Press. ISBN 978-1-900867-05-4. OCLC 52531228.

- de Kerbrech, Richard (2009). Ships of the White Star Line. Shepperton: Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7110-3366-5. OCLC 298597975.

- Eaton, John P; Haas, Charles A (1989). Falling Star, Misadventures of White Star Line Ships. Sparkford: Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85260-084-6. OCLC 20935102.

- Harnack, Edwin P (1949) [1903]. All About Ships & Shipping (8th ed.). London: Faber and Faber.

- Haws, Duncan (1990). White Star Line. Merchant Fleets. Vol. 17. TCL Publications. ISBN 978-0-946378-16-6. OCLC 50214776.

- Talbot-Booth, EC (1936). Ships and the Sea (Third ed.). London: Sampson Low, Marston & Co Ltd.

- Wilson, RM (1956). The Big Ships. London: Cassell & Co.

External links

![]() Media related to Britannic (ship, 1930) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Britannic (ship, 1930) at Wikimedia Commons