Ancient Egyptian race controversy: Difference between revisions

→Gallery of ancient Egyptian art: revert edit by IP, check the site it is clearly an Afrocentrist site |

reverting vandalism of the gallery. Anwar go to the discussion page. If you continue to make disruptive edits we're going to report you. |

||

| Line 111: | Line 111: | ||

File:GD-EG-Louxor-116.JPG|Bust of [[Senusret III]]; fifth monarch of the Twelfth Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom. |

File:GD-EG-Louxor-116.JPG|Bust of [[Senusret III]]; fifth monarch of the Twelfth Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom. |

||

File:Louvre 032007 15.jpg|Sphinx of pharaoh [[Nepherites I]] in the Louvre museum; founded the Twenty-ninth dynasty |

File:Louvre 032007 15.jpg|Sphinx of pharaoh [[Nepherites I]] in the Louvre museum; founded the Twenty-ninth dynasty |

||

File:Mannequin of Tutankhamun.jpg|Bust of Tutankhamun. |

|||

</gallery></center> |

|||

File:Amenhotep III.jpg| Amenhotep III</gallery></center> |

|||

==Population history of Egypt== |

==Population history of Egypt== |

||

Revision as of 18:04, 8 May 2009

The Race of the ancient Egyptians is a subject that has attracted some controversy within mainstream academia and the broader society. The ancient Egyptians depicted themseves as having a different appearance to the other nations around them. The modern mainstream opinion is that the ancient Egyptians were a mixed race, being neither black nor white as per current terminology, and that ancient Egypt was a Classical African Civilization.[1][2] Some scholars disagree, and have made various contrary inferences from biological, cultural and linguistic data.

The definition of race

The scholarly consensus is that the concept of biologically distinct races isn't applicable to modern humans.[3][4] Human populations do differ in phenotypic traits and gene frequencies, but most human variation is found within populations rather than between population.

It has also become evident that modern racial classifications are often social constructs based on arbitrary criteria. Criteria for racial classification differ from region to region and also criteria can change with time.[5][6] Consequently, many scholars agree that it is misleading to apply modern notions of race to the Ancient Egyptians.

Historically whenever different human populations have come in close contact for extended periods of time, they have interbred freely. Human phenotypes thus vary in clines, whereby populations that live closer to each other are likely to be more similar genetically than populations that live farther apart. A population that lives in between two populations is likely to share traits with both neighboring populations. In addition to gene flow, environmental factors such as climate also influence the variation in human phenotype. Most notably, human skin color on average varies clinally with the intensity of sunlight (i.e. with latitude,).

Modern Egyptians, thousands of years after dynastic times, demonstrate clinal patterns in phenotypic traits such as skin color and craniofacial morphology, with modern Southern Egyptians on average having darker skin and facial features more consistent with tropical Africans than modern Northern Egyptians.[7]

Origins of the debate

The classical observers

- Herodotus travelled to Egypt around 450 BC, about 2000 years after the Pyramid Age and when Egypt was part of the Persian Empire. In his writings about the Egyptians, he described them as having "black skins and woolly hair".

- The Greek playwright Aeschylus [525 BC - 455 BC], (also at the time of the Persian Empire) mentioning a boat seen from the shore, declared that its crew are Egyptians, because of their black complexions.[8]

- Josephus regarded the Egyptians in his day (1st century) as descendants of Mizraim, son of Ham on the basis of Genesis 10, which remained the basis for most scholarship in the Middle Ages.

- Strabo, (c. 64 BC – AD 24), the Roman historian and geographer, wrote in his work Geographica that “As for the people of India, those in the south are like the Aethiopians in colour, although they are like the rest in respect to countenance and hair (for on account of the humidity of the air their hair does not curl), whereas those in the north are like the Aegyptians.” (Strabo, Book XV, Chapter 1, Section 13.)[9]

- Arrian, (c. 86 AD – 146 AD), one of the main ancient historians of Alexander the Great, wrote in his work Indica that “the southern Indians resemble the Ethiopians a good deal, and are black of countenance, and their hair black also, only they are not as snub-nosed or so woolly-haired as the Ethiopians; but the northern Indians are most like the Egyptians in appearance."

The colonial period

In 1798 Constantin Francois de Chassebœuf, Comte de Volney, published his book Travels Through Syria and Egypt in the Years 1783, 1784, and 1785, in which he documented his experiences. In the book he states that in his opinion the Great Sphinx has "negroid" facial characteristics. He also describes the modern-day Egyptians he encountered as appearing to be of mixed race.[10]

The Egyptian pyramid used in the Great Seal of the USA and the Washington monument indicate that American society of the colonial period held the Ancient Egyptian culture in high regard. The industrialized west, being predominantly Caucasian, had historically held a low regard for black people, many of whom were slaves. In the early 19th century slavery was still legal in the United States, and was being justified in part on the assumption that Black people were intellectually inferior. The anti-slavery movement was gaining momentum, and pro-slavery advocates were thus unreceptive to any suggestion of advanced Black civilizations that would undermine this rationale. In 1844 Samuel George Morton, a proslavery supporter and one of the pioneers of scientific racism and polygenism, published his book Crania Aegyptica with the intention of “proving” that the Ancient Egyptians were not Black.[11] In 1855 George Gliddon and Josiah C. Nott published Types of Mankind with the same intention.[12] All three authors acknowledged that Negroes were present in ancient Egypt, but claimed they were either captives or servants. However, they also concluded that the Egyptians were intermediate between the African and Asiatic races. [13]

In England, Charles Darwin and others concluded that a statue of Amunoph (Amenhotep III) had strongly marked Negro-type features.[14][15] In 1886, George Rawlinson wrote that the physical type, language and tone of thought of the modern Egyptians is “Nigritic”. Though he believed the modern Egyptians were not Black, he stated that they bear an “indisputable” resemblance to Black Africans.[16]

In 1905 David Randall-MacIver analysed the remains of at least 1560 individuals from Thebes (in Upper Egypt) to determine the race of the deceased. Based on the elaborateness of the graves, he concluded that during predynastic periods Negroid people were the social equal of others, and were equally represented among the lower and higher classes. According to McIver's study, the Negroid element in Upper Egypt was very pronounced in predynastic periods, but had significantly diminished by Roman times.[17]

Afrocentrism

Afrocentrism is a world view that emphasizes the contributions of African people through history and has contributed considerably to the controversy.[18][19]

Modern scholarship

Since race is not considered to be a valid scientific concept by most scientists, the focus of some experts who study population biology has been to seek an answer to the question of whether or not the Ancient Egyptians were primarily biologically African rather than which race they belonged to.[20]

The race of the ancient Egyptians was addressed at UNESCO’s international Cairo Symposium in 1974, where more than 20 of the world’s top Egyptologists debated inter alia the race of the founders of ancient Egyptian civilization. The majority view was that the ancient Egyptians were a mixed race, being neither black nor white as per current terminology.[21][22] However a few scholars before and since have continued to assert otherwise, and have variously proposed that the ancient Egyptians were black, Asian, Mediterranean, Atlantean or even aliens from space.

While some Egyptian Egyptologists such as Zahi Hawass insist that the Ancient Egyptians did not fit neatly into a racial group and that Ancient Egypt was not even an African Civilization, there is a growing scholarly consensus among academics of various fields that Ancient Egypt is also a Classical African Civilization, along with Numidia and Nubia (Kerma/Kush/Meroe). They also contend that Egypt had cultural and biological connections with its African neighbors.[23]

A collection of essays published under the title Egypt in Africa included contributions from leading experts in various fields, including Chike Aniakor, Molefi Kete Asante, Robert Steven Bianchi, Arthur P. Bourgeois, Shomarka Keita, Christopher Ehret, Chapurukha M. Kusimba, Frank M. Snowden, Jr., and Frank J. Yurco. While the contributors differed in some opinions the scholarly consensus was that Ancient Egypt was and should be considered a Classical African Civilization.[24]

In 1996 Indianapolis museum of art curator Theodore Celenko held an exhibition titled Egypt in Africa in order to present works of art that emphasized Egypt’s cultural connection to the rest of the African continent. [25][26]

Ancient Egyptian material

The ancient tombs and temples contained thousands of works of writing, painting and sculpture, which reveal a lot about the people of that time. However their depictions of themselves in their surviving art and artifacts are rendered in sometimes symbolic, rather than realistic, pigments. As a result, ancient Egyptian artifacts provide sometimes conflicting and inconclusive evidence of the ethnicity of the people who lived in Egypt during dynastic times.[27][28][29][30][31]

Meaning of 'Kemet'

| km biliteral | km.t (place) | km.t (people) | |||||||||

|

|

|

One of the many names for Egypt in ancient Egyptian is km.t (read Kemet), meaning 'the black land' or 'the black one'. The claim that Kemite referred to the fact that the people of the land were black, as argued by Cheikh Anta Diop, William Leo Hansberry, Yaacov Shavit or Aboubacry Moussa Lam has become a cornerstone of Afrocentric historiography.[32][33][34]

This view is rejected by most Egyptologists.[35] Generally, 'Kemet' is taken to be a reference to the fertile black soil, which was washed down from Central Africa by the annual Nile inundation, and which made Egypt habitable and prosperous in contrast to the barren desert or 'red land' outside the narrow confines of the Nile watercourse. The use of the word kmt when referring to people is thought to be derived from the name of the land, meaning literally "those people who live in the black, fertile country."[32] Raymond Faulkner's Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian translates it into "Egyptians", as do most sources.[36]

Ancient Egyptian texts and inscriptions

There are a number of surviving copies of a sacred text from Dynastic times called the Book of Gates. These were usually carved and/or painted inside tombs, for the guidance of the soul of the deceased. [37][38][39] Among other things they described the "four races of men", as follows: (translation by E.A. Wallis Budge):

The first are RETH, the second are AAMU, the third are NEHESU, and the fourth are THEMEHU. The RETH are Egyptians, the AAMU are dwellers in the deserts to the east and north-east of Egypt, the NEHESU are the black races, and the THEMEHU are the fair-skinned Libyans.

The Land of Punt

The ancient Egyptians viewed the Land of Punt (Pun.t; Pwenet; Pwene) as their ancestral homeland.[40][41][42] In his book “The Making of Egypt” (1939), W. M. Flinders Petrie stated that the Land of Punt was “sacred to the Egyptians as the source of their race.” E.A. Wallis Budge stated that “Egyptian tradition of the Dynastic Period held that the aboriginal home of the Egyptians was Punt…”[43] Per Emmet John Sweeney: “The Horus Kings of the First Dynasty insisted their ancestors came from the Land of Punt.”[44]

The exact location of Punt remains a mystery. The mainstream view is that Punt was located to the south-east of Egypt, most likely in the Horn of Africa.

However some scholars disagree with this view and point to a range of ancient inscriptions which locate Punt in Arabia. Dimitri Meeks has written that “Texts locating Punt beyond doubt to the south are in the minority, but they are the only ones cited in the current consensus about the location of the country. Punt, we are told by the Egyptians, is situated – in relation to the Nile Valley – both to the north, in contact with the countries of the Near East of the Mediterranean area, and also to the east or south-east, while its furthest borders are far away to the south. Only the Arabian Peninsula satisfies all these indications.”[45]

The placement of Punt in eastern Africa is based on the fact that the products of Punt were abundantly found in East Africa but were less common or absent in Arabia. These products included gold, aromatic resins such as myrrh, ebony and elephant tusks. The wild animals depicted in Punt include giraffes, baboons, hippopotami and leopards which were common in East Africa but are less frequent or completely absent in Arabia. Says Richard Pankhurst, in his book “The Ethiopians”: “[Punt] has been identified with territory on both the Arabian and African coasts. Consideration of the articles which the Egyptians obtained from Punt, notably gold and ivory, suggests, however, that these were primarily of African origin. … This leads us to suppose that the term Punt probably applied more to African than Arabian territory.”[46][47][48][49]

In 2003 reports emerged of a tomb that was discovered at El Kab (near Thebes) dating to the 17th dynasty (1575-1525 BC). It contained an inscription describing a huge attack from the south "by the Kingdom of Kush and its allies from the land of Punt".[50] Encyclopaedia Britannica describes Punt as follows: “in ancient Egyptian and Greek geography, the southern coast of the Red Sea and adjacent coasts of the Gulf of Aden, corresponding to modern coastal Ethiopia and Djibouti.”[51]

The consensus view among the majority of Egyptologists is summed up by Ian Shaw from the Oxford History of Ancient Egypt:

There is still some debate regarding the precise location of Punt, which was once identified with the region of modern Somalia. A strong argument has now been made for its location in either southern Sudan or the Eritrean region of Ethiopia, where the indigenous plants and animals equate most closely with those depicted in the Egyptian reliefs and paintings.[52]

Ancient Egyptian art

In the many surviving tomb paintings, papyri and statues, the ancient Egyptians depicted themselves in a wide variety of colors, but the predominant color used for Egyptian men was reddish-brown, while the Egyptian women are usually portrayed with much lighter skin pigmentation. The Egyptians often distinguished themselves from the neighboring populations. Generally, Egyptians depicted themselves as darker than Asiatics, and Libyans but lighter than the Nubians. [53]However, Egyptian artists also depicted both themselves and non-Egyptians in other colors, as well as sometimes using unrealistic colors such as blue and green. The use of all these colors is presumed to sometimes have symbolic meaning, but is not completely understood.[54]

Gallery of ancient Egyptian art

-

“Rahotep, husband of Nofret", from the 4th Dynasty, with much darker skin than his wife.

-

“Nofret, wife of Rahotep", from the 4th Dynasty, with much lighter skin than her husband.

-

A rural mural, showing the women as being pale-skinned but the men brownish-red.

-

“Seneb the scribe”, 4th Dynasty. The gender-based skin coloring is reflected in both the adults and the children.

-

A Grave mask of pharaoh Amenemope of the 21st Dynasty of Egypt.

-

From the tomb of Akmenthor the Physician – c. 2330 B.C.

-

Glass statuettes from Medinet Habu, 19th Dyn. From left: a pair of Nubians, a Philistine, an Amorite, a Syrian and a Hittite.

-

Nefertiti, wife of Akhenaten, Ägyptisches Museum Berlin.

-

Queen Tiye, believed to be Akhenaten's mother, wearing a Nubian enveloping wig[57] Ägyptisches Museum, Berlin.

-

Statue Head of the pharaoh Amenmesse, from the 19th dynasty, circa 1203-1200 B.C.

-

Asiatics shown entering Egypt, the tomb Khnumhotep II. Egyptians, top right, are depicted as darker than the Asiatic peoples.

-

Bust fragment of Prince Khaemwase, one of the sons of Rameses II, New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty. Altes Museum, Berlin.

-

Portrait of a pharaoh, probably Rameses VI. Painted shard of limestone, 1143–1136 BC (20th Dynasty).

-

Tutankhamun's Golden burial mask.

-

Bust of Senusret III; fifth monarch of the Twelfth Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom.

-

Sphinx of pharaoh Nepherites I in the Louvre museum; founded the Twenty-ninth dynasty

-

Bust of Tutankhamun.

-

Amenhotep III

Population history of Egypt

Egypt has experienced several mass migrations and invasions during its history, including by the Canaanites, the Libyans, the Nubians, the Assyrians, the Kushites, the Persians, the Greeks and the Romans. The last of these occurred in 639 AD, when the region was invaded by Muslim Arabs. Following the Arab invasian, the Egyptian language, and its descendant Coptic became extinct. The various conquests have made the relationship between Modern Egyptians and Ancient Egyptians unclear, and this has become an important part of the controversy over the race of the ancient Egyptians.

The debate centers on whether the cultural changes (religion and language) were the result of mass movements of people, or whether the cultural changes were the result of cultural diffusion with only minor demographic changes. For example, Afrocentrists such as Ivan van Sertima argue that the Egyptians were primarily Africoid before the many conquests of Egypt diluted the Africanity of the Egyptians.[58]. Others believe that Modern Egyptians are the direct descendants of the Ancient Egyptians, with the various foreign migrations having had little impact on the Egyptian population.[59]

Prehistory

During the Paleolithic the Nile Valley was inhabited by various hunter gatherer populations. About 10,000 years ago the Sahara Desert had a wet phase. People from the surrounding areas moved into the Sahara, and evidence suggests that the populations of the Nile Valley reduced in size. Rock paintings from Algeria at Tassili n'Ajjer reveal that some of the Saharan population were black Africans. It is unclear when Caucasoid populations, such as the ancestors of Berbers, first arrived in North Africa from Eurasia. There are two theories, one is that the ancestors of the Berbers have been present in North Africa since paleolithic times, the other theory is that the Caucasoid populations only reached North Africa during the Neolithic, when they brought domesticated cereals and animals from the Near East. About 5,000 years ago the wet phase of the Sahara came to end. Saharan population retreated to the south towards the Sahel, and East towards the Nile Valley. It is these populations that played a major role in the formation of the Egyptian state as they brought their food crops and cattle to the Nile Valley.[24]

Predynastic Egypt

The predynastic period dates to the end of the fourth millenium BC. From about 5000 to 4200BC the Merimde Culture flourished in Lower Egypt. This culture has links to Palestine.[60] The pottery of the Buto Maadi Culture, best known from the site at Maadi near Cairo, also shows strong connections to South Palestine.[61]

In Upper Egypt the predynastic Badarian culture was followed by the Naqada culture. The origins of these people is still not fully understood, but their crops came originally from the Near East. There was also significant contact between the peoples of the Naqada culture and the Nubian A-Group people. The origins of the Egyptian dynastic state can be traced to the Naqada culture.

Some have suggested that the Nubian A-Group conquered the Naqada and then went on to conquer Lower Egypt to begin the dynastic era. However this view is disputed by many scholars. Some studies have however described human remains from both the Naqada and Badarian cultures as clustering with Nubians or Negroids than with Northern Egyptian remains.[62]

DNA studies

Attempts to extract ancient DNA or aDNA from Ancient Egyptian remains have yielded little or no success. Climatic conditions and the mummification process could hasten the deterioration of DNA. Contamination from handling and intrusion from microbes have also created obstacles to recovery of Ancient DNA. [63]Consequently most DNA studies have been carried out on modern Egyptian populations with the intent of learning about the influences of historical migrations on the population of Egypt.[64][65][66] [67] However, there was one notable study of ancient dynastic mummies performed by Paabo and Di Rienzo who identified multiple lines of descent, including some from sub-Saharan Africa.[68] Unfortunately, the other lineages were not identified but according to Keita (1996) they may also have been African in origin.[69]

DNA studies on modern Egyptians

In general, various DNA studies have found that the gene frequencies of North African populations are intermediate between those of Sub-Saharan Africa and Eurasia,[70] though possessing a greater genetic affinity with the populations of Eurasia than they do with Sub-Saharan Africans.[71][72][73][74][71][75]

A study by Krings et al. from 1999 on mitochondrial DNA clines along the Nile Valley found that a Eurasian cline runs from Northern Egypt to Southern Sudan, and a Sub-Saharan cline extends from Southern Sudan to Northern Egypt. [76] Another study based on maternal lineages links modern Egyptians with people from modern Eritrea/Ethiopia such as the Afro-Asiatic-speaking Tigre.[77] Similarly, an mtDNA study of modern Egyptians from the Gurna region near Thebes in Southern Egypt revealed that Eurasian haplogroups represented 61% of the population, with the remainder 39% being of Sub-Saharan origin. The oral tradition of the Gurna people indicates that they descend from the ancient Egyptians [78]

A study using the Y-chromosome of modern Egyptian males found similar results, namely that African haplogroups are predominant in the South but the predominant haplogroups in the North are characteristic of other North African populations.[79].

A study of Coptic ethnic group in Sudan found relatively high frequencies of Sub-Saharan Haplogroup B (Y-DNA). The Copts are descendants of Egyptians who have recently migrated from Egypt. According to the study, the presence of Sub-Saharan haplogroups is consistent with the historical record in which southern Egypt was colonized by Nilotic populations during the early state formation.[80]

The results of these genetic studies is consistent with the historical record, which records significant bidirectional contact between Egypt and Nubia within the last few thousand years.[76][79]

Anthropometric indicators

Historical attempts using anthropometric studies to distinguish different races have been controversial because considerable variation in anthropometric measurements is found in any geographic population. However, some scholars believe anthropometric measurements are still useful in determining the biological affinities between different populations.

Craniofacial criteria

In 1912 Franz Boas demonstrated that cranial shape is heavily influenced by environmental factors, and therefore cranial measurements cannot be a reliable indicator of inherited influences such as race.[81] This conclusion was supported in 2003 in a paper by Gravlee, Bernard and Leonard.[82][83]

A survey cited by Kemp (2005) of ancient Egyptian crania spanning all time periods found that the Egyptian population as a whole clusters more closely to the Nubian and Ethiopic groups of the Nile valley than to Asian and Mediterranean groups, but that they also cluster more closely to the Asian and Mediterranean groups than they did to the Negroid and Archaic African groups. Kemp also noted that Egypt conquored and settled Nubia beginning in the 1st Dynasty.[84]

Anthropologist Nancy Lovell states the following:

[Data] "must be placed in the context of hypotheses informed by archaeological, linguistic, geographic and other data. In such contexts, the physical anthropological evidence indicates that early Nile Valley populations can be identified as part of an African lineage, but exhibiting local variation. This variation represents the short and long term effects of evolutionary forces, such as gene flow, genetic drift, and natural selection, influenced by culture and geography." [85]

This view was also shared by the late Egyptologist, Frank Yurco.[86]

A 2005 study by Keita of predynastic Badarian (Southern Egyptian) crania found that the Badarian samples cluster more closely with the tropical African samples than with European samples, although no Asian samples were included.[87]

Sonia Zakrzewski in 2007 noted that genetic continuity occurs over the Egyptian Predynastic and Early Dynastic periods, but that a relatively high level of genetic differentiation was sustained over this time period. She concluded therefore that the process of state formation itself may have been mainly an indigenous process, but that it may have occurred in association with in-migration, particularly during the Early Dynastic and Old Kingdom periods.[88]

However a craniofacial study by C. Loring Brace et. al. (1993) concluded that: "The Predynastic of Upper Egypt and the Late Dynastic of Lower Egypt are more closely related to each other than to any other population. As a whole, they show ties with the European Neolithic, North Africa, modern Europe, and, more remotely, India, Somalia, eastern Asia, Oceania, or the New World."[89]

Anthropologist Shomarka Keita and others have pointed out the apparent contradictions of these conclusions, and have also pointed out that such relationships need not necessarily suggest gene-flow.[90]

In 2008 Keita again found that the early predynastic/dynastic groups in Southern Egypt were similar craniometrically to African Nilotic groups, but concluded that more material is needed to make a firm conclusion about the relationship between the early Holocene Nile valley populations and later ancient Egyptians.[91]

Limb ratios

Anthropologist C. Loring Brace points out that such limb elongation is "clearly related to the dissipation of metabolically generated heat" in areas of higher ambient temperature. Also stating that "skin color intensification and distal limb elongation is apparent wherever people have been long-term residents of the tropics", and curiously this has been observed among Egyptian samples.[92] According to Robins and Shute the average limb elongation ratios among ancient Egyptians is higher than that of modern West Africans who reside much closer to the equator. Robins and Shute therefore term the ancient Egyptians to be "super-negroid" but state that although the body plans of the ancient Egyptians were closer to those of modern negroes than for modern whites, “this does not mean that the ancient Egyptians were negroes".[93] Anthropologist S.O.Y. Keita criticized Robins and Shute, stating they they do not interpret their results within an adaptive context, stating that that they imply “misleadingly” that early southern Egyptians were not a "part of the Saharo-tropical group, which included Negroes".[94] Gallagher et al also points out that "body proportions are under strong climatic selection and evidence remarkable stability within regional lineages".[95] Zakrzewski later confirmed the results of Robins and Shute, again referring to the proportions as "super-negroid", assessing continuity well into the dynastic period and affirming that the Ancient Egyptians in general had "tropical body plans".[96]

Trikhanus (1981) found Egyptians to plot closest to tropical Africans and not Mediterranean Europeans residing in a roughly similar climatic area.[97] A more recent study compared ancient Egyptian osteology to that of African-Americans and White Americans, and found that the stature of the Ancient Egyptians was more similar to the stature of African-Americans, although it was not identical.[98]

Dental morphology

A 2006 bioarchaeological study on the dental morphology of ancient Egyptians by Prof. Joel Irish shows dental traits characteristic of indigenous North Africans and to a lesser extent Southwest Asian and southern European populations. Among the samples included in the study is skeletal material from the Hawara tombs of Fayum, (from the Roman period) which clustered very closely with the Badarian series of the predynastic period. All the samples, particularly those of the Dynastic period, were significantly divergent from a neolithic West Saharan sample from Lower Nubia. Biological continuity was also found intact from the dynastic to the post-pharaonic periods. According to Irish:

[The Egyptian] samples [996 mummies] exhibit morphologically simple, mass-reduced dentitions that are similar to those in populations from greater North Africa (Irish, 1993, 1998a–c, 2000) and, to a lesser extent, western Asia and Europe (Turner, 1985a; Turner and Markowitz, 1990; Roler, 1992; Lipschultz, 1996; Irish, 1998a).[99]

Irish has been criticized in the past however, by anthropologist Shomarka Keita for a limited approach in the interpretation of these results. Taking issue with Irish et al suggestion that Egyptians and Nubians were not primary descendants of the African epipaleolithic and Neolithic populations. Keita criticizes them for ignoring the well-known post-pleistocene hunting/dental reduction and simplification hypothesis which postulate in situ microevolution driven by dietary change, with minimal gene flow (admixture) while citing among the ancient Egyptians the presence of fourth molars and alveolar pits behind the third molars. These are referred to as "fourth molar variants" and are much more common among more southernly Africans than in Europeans.[20]

The language element

The ancient Egyptian language has been classified as a member of the Afro-Asiatic language family. The Afro-Asiatic languages constitute a language family with about 375 living languages (SIL estimate) and more than 300 million speakers spread throughout North Africa, the Horn of Africa, and Southwest Asia (including some 150 million speakers of Arabic dialects). Afro-Asiatic also includes several ancient languages, such as Ancient Egyptian, Biblical Hebrew, and Akkadian (the language of the Babylonians and Assyrians).

The Afro-Asiatic languages comprise the following sub-families.

The Afro-Asiatic language family is believed by most linguists to have originated in Northeast Africa with a minority postulating an origin in the Levant (ancient Canaan).[100][101][102]

Of the six subfamilies of Afro-Asiatic, the Semitic languages form the only Afro-Asiatic subfamily that exists in both Africa and Asia. The other five of the six Afro-Asiatic subfamilies are restricted to the African continent. The majority of the diversity in the Afro-Asiatic language family is found in Ethiopia, where diverse languages exist in close geographic proximity. [103]

UCLA Professor of African history, Christopher Ehret, claims that the Ancient Egyptians are descended from speakers of Proto-Afroasiatic who migrated from further south to the Nile Valley. According to Ehret archeological and linguistic evidence indicates that the speakers of the earliest Afroasiatic languages occupied lands between Nubia and northern Somalia around 15,000-13,000 B.C. before the formation of the Ancient Egyptian state.[104]

In Black Athena Professor Martin Bernal argues that the phylum may instead have emerged around the Great Rift Valley in southern Ethiopia and northern Kenya.[105]

On his part, Théophile Obenga writes that the Egyptian language and the Negro-African languages derive from a common pre-dialectal ancestor he names “négro-africain ”. According to him, the Afro-Asiatic language family has no scientific base and was created with the purpose of cutting off culturally the Egypt-Nubian Nile Valley from the rest of Africa.[106]

Biogeographic origin based on cultural data

Located in the extreme north-east corner of Africa, ancient Egyptian society was at a crossroads between the African and Near Eastern regions. Early proponents of the Dynastic Race Theory based their hypothesis on the increased novelty and seemingly rapid change in pre-dynastic pottery and noted trade contacts between ancient Egypt and the Middle East.[107] This is no longer the dominant view in Egyptology, however the evidence on which it was based still suggests influence from these regions.[108] Fekri Hassan and Edwin et al point to mutual influence from both inner Africa as well as the Levant.[109] However according to one author this influence seems to have had minimal impact on the indigenous populations already present.[110]

One author has stated that the Naqada phase of predynastic Egyptians in Upper Egypt shared an almost identical culture with A-group peoples of the Lower Sudan.[111] Based in part on the similarities at the royal tombs at Qustul, some scholars have even proposed an Egyptian origin in Nubia among the A-group.[112][113] In 1996 Lovell and Prowse reported the presence of individual rulers buried at Naqada in what they interpreted to be elite, high status tombs, showing them to be more closely related morphologically to populations in Northern Nubia than those in Southern Egypt.[114] Most scholars however, have rejected this hypothesis and cite the presence of royal tombs that are contemporaneous with that of Qustul and just as elaborate, together with problems with the dating techniques.[115]

The language of the Nubian people is one of the Nilo-Saharan languages, whereas the language of the Egyptian people was one of the Afro-Asiatic languages.

Toby Wilkonson, in his book "Genesis of the Pharaohs", proposes an origin for the Egyptians somewhere in the Eastern Desert.[116] He presents evidence that much of predynastic Egypt duplicated the traditional African cattle-culture typical of Southern Sudanese and East African pastoralists of today. Kendall agrees with Wilkinson's interpretation that ancient rock art in the region may depict the first examples of the royal crowns, while also pointing to Qustul in Nubia as a likely candidate for the origins of the white crown, being that the earliest known example of it was discovered in this area.

Excavations from Nabta Playa, located about 100km west of Abu Simbel, suggest that the Neolithic inhabitants of the region were migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa. However there is also evidence that sheep and goats were introduced into Nabta from Southwest Asia about 8000 years ago.[117] There is some speculation that this culture is likely to be the predecessor of the Egyptians, based on cultural similarities and social complexity which is thought to be reflective of Egypt's Old Kingdom.[118][119]

Specific modern controversies

There have been numerous controversies regarding the race of specific notable individuals from the history of Egypt, particularly the Great Sphinx, Tutankhamun, Ramses the Great and Cleopatra VII. [120]

The Great Sphinx of Giza

A number of writers have described the face of the Sphinx as having features that are Ethiopian, Nubian, African or Negro, as opposed to Grecian, Coptic or Arab (Semitic). These writers include the French philosopher Constantin-François Chassebœuf, [121] Gustave Flaubert,[122] and W.E.B. Du Bois.[123]The exact identity of the model for the Sphinx is unknown as there are no known written records that proclaim its identity. Many Egyptologists and scholars currently believe that the face of the Sphinx represents the likeness of the Pharaoh Khafre, whose statues have been located near the Sphinx and who is held to be the creator of the statue. A few Egyptologists and interested amateurs have made several conflicting hypotheses regarding the identity of the Sphinx, but at present, no definitive proof exists.[124]

Forensic artist Frank Domingo, a retired detective for the NYPD, drew a profile sketch of both The Sphinx and Khafre's statue in order to compare the dimensions of the faces to determine whether or not they depicted the same person. Domingo concluded that The Sphinx had a significantly greater degree of prognathism (forward projection of the jaw) than Khafre's statue, suggesting that the statues did not depict the same person. In 1992, the New York Times published a letter to the editor submitted by Sheldon Peck, a Harvard professor of orthodontics[125], who noted of the Sphinx that it shows “an anatomical condition of forward development in both jaws, more frequently found in people of African ancestry than in those of Asian or Indo-European stock."[126] Other authors have pointed out that the face of the Sphinx is angled upwards, and that if the face is angled vertically then the jaw appears very similar to that of the statues of Khafra.[127]

Tutankhamun

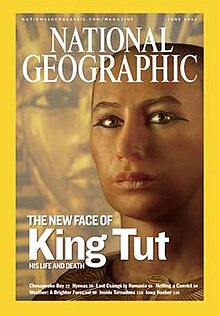

Supporters of Afrocentrism have claimed that Tutankhamun was black, and have protested that attempted reconstructions of Tutankhamun's facial features (as depicted on the cover of National Geographic Magazine) have represented the king as “too white”.[128]

Forensic artists and physical anthropologists from Egypt, France, and the United States independently created busts of Tut, using a CT-scan of the skull. Based on Tut's cranial features, specifically his narrow nose opening, he was classified as racially Caucasoid. Although modern technology can reconstruct Tutankhamun's facial structure with a high degree of accuracy based on CT data from his mummy,[129][130] determining his skin tone and eye color is impossible. The clay model was therefore given a flesh coloring which according to the artist was based on an "average shade of modern Egyptians."[131]

Biological anthropologist Susan Anton, the leader of the American team, said that the race of the skull was “hard to call”. She stated that: "The shape of the cranial cavity indicated an African, while the nose opening suggested narrow nostrils; a European characteristic. The skull was a North African." [132]

Other biological anthropologists point out that narrow noses are a common trait among indigenous Northeast Africans, and a product of adaptation to the hot-dry climate of the region. Therefore the shape of Tut's nose does not necessarily reflect European ancestry nor rationalize classification as a Caucasian.[20]

Other experts point out that dolichocephalic skull shapes are a common trait among European and Middle Eastern indigenous populations, and that skull shapes are therefore not a reliable indicator of Tut's race or ancestry.[133]

In a press release of May 2005, the current Secretary General of the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities, Dr. Zahi Hawass, said that: “The three reconstructions (French, America and Egyptian) are all very similar in the unusual shape of the skull, the basic shape of the face, and the size, shape and setting of the eyes … In my opinion as a scholar, the Egyptian reconstruction looks the most Egyptian, and the French and American versions have more unique personalities.[134]

When pressed on the issue by American activists Zahi Hawass in September 2007, stated that "Tutankhamun was not black, and the portrayal of ancient Egyptian civilization as black has no element of truth to it …. Egyptians are not Arabs and are not Africans despite the fact that Egypt is in Africa."[135]

Ahmed Saleh, the former archaeological inspector for the Supreme Council of antiquities, disagrees with many of Hawass' statements, stating that the procedures used in the facial re-creation made Tut look Caucasian, "disrespecting the nation's African roots".[136]

In a November 2007 publication of "Ancient Egypt Magazine", Hawass asserted that none of the facial reconstructions resemble Tut, claiming for example that the French reconstruction ended up with a person that looked French, whose features do not resemble any known Egyptians. He asserted instead that in his opinion, the most accurate representation of the boy king is the mask from his tomb.[137]

The Discovery Channel commissioned a facial reconstruction of Tutankhamun's golden mask back in 2002.[138]

Rameses the Great

Several commentators have noted that the mummy of Rameses the Great (of the 19th Dynasty) has red or blond hair.[139][140] Frank Yurco describes the mummy of Rameses as having “fine, wavy hair, a prominent hooked nose and moderately thin lips.” Yurco also describes Rameses as being “a typical northern Egyptian”. Although Rameses ruled from Thebes in Upper Egypt, he was originally from the extreme north-east of the country. [141]

In 1975 the mummy of Rameses the Great was taken to Paris for conservation and the treatment of fungal infestations. A detailed examination of the mummy showed that his hair had been grey at the time of his death, and had been dyed red using plant extracts, but scientific analysis showed that the original natural color of the hair before going grey was also red. [142] In a dispute over nuance however, others have described the color as auburn (or brownish-red) who according to Spindler and others, have lead some to reach "far-flung conclusions".[143].Tyldesley sites, that neither red or auburn hair was common in dynastic Egypt and that "Ramses would have looked conspicuous among his dark-haired companions".[144] Given many other peculiarities, it has been stated by some scholars that Ramses II may have been the product of intermarriage, citing Asiatic characteristics and that he and his predecessors Seti I and Merenptah appeared less typically Egyptian than that of the 18th Dynasty Pharaohs.[145][146]

Cleopatra VII

Some Afrocentric scholars and supporters have claimed that Cleopatra, the last of the pharaohs, was Black. In her book Not Out of Africa, Professor Mary Lefkowitz points out that Cleopatra’s ancestors, the rulers of the Ptolemaic dynasty, were Macedonian Greeks descended from Ptolemy I, one of Alexander the Great's generals.[147] Lefkowitz states that:

- it was their practice to marry close relatives – brother with sister or uncle with niece, etc.

- the only possibility that Cleopatra VII might not have been a full-blooded Macedonian Greek arises from the fact that we do not know the precise identity of her grandmother on her father's side, as this lady was the mistress (not the wife) of her grandfather, Ptolemy IX.

- because of the incestuous custom of the Ptolemy family it is generally assumed that this grandmother was also a relative, but it is possible that she might have been of another race - no evidence has ever arisen either way.

In 2009 a BBC documentary speculated that Arsinoe IV, the half-sister of Cleopatra VII, may have been part African, and then further speculated that Cleopatra’s mother and thus Cleopatra herself might also have been part African. This was based largely on the claims of Hilke Thuer of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, who in the 1990's had examined a headless skeleton of a female child in a 20BC tomb in Ephesus (modern Turkey) together with the old notes and photographs of the now-missing skull.[148][149]

However, a writer from the London Times described the identification of the skeleton as “a triumph of conjecture over certainty”.[150]

The assumption of the skeleton's identity was based on the shape of the tomb (octagonal, like the Lighthouse of Alexandria), the timing of the death (around 20BC), the gender of the skeleton, and the age of the child at death (although some commentators consider the age of the child to be rather young, considering what Arsinoe is described by history as having accomplished in her life.)[151]

The recent cranial analysis was done based measurements, notes and photographs made before the skull itself was lost during World War 2.[152][153][154] Boas, Gravlee, Bernard and Leonard and others have demonstrated that skull measurements are not a reliable indicator of race.[155][156] (See also Anthropometrics above.)

Arsinoe IV was actually the half-sister of Cleopatra VII, sharing a father (Ptolemy XII Auletes) but having a different mother.[157]

References

- ^ General history of Africa, by G. Mokhtar, International Scientific Committee for the Drafting of a General History of Africa, Unesco

- ^ Afrocentrism, by Stephen Howe

- ^ Race and Human Variation

- ^ Keita (2004). "Conceptualizing human variation" (PDF). doi:10.1038/ng1455.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Race without color

- ^ Race and ethnicity

- ^ Were the Ancient Egyptians Black or White?

- ^ Anthon, Charles (1851). "Complexion and Physical Structure of the Egyptians". A classical dictionary.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Strabo/15A1*.html

- ^ Diop, Cheikh Anta. Nations Nègres et Culture, tome I, Paris 1979, 57-58.

- ^ Trafton, Scott (2004). Egypt Land: Race and Nineteenth-century American Egyptomania. ISBN 0822333627.

- ^ General Remarks on "Types of Mankind"

- ^ Morton, Samuel George (1844). "Egyptian Ethnography".

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|title=(help); Unknown parameter|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ The Descent of Man

- ^ Nott (1855). "Negro Types". Types of Mankind.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Rawlinson, George (1886). "The People of Egypt". Ancient Egypt.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ MacIver. "chapter 9". The Ancient Races of the Thebaid.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African-American Volume 1., p. 111 by Henry Louis Gates (Editor), Kwame Anthony Appiah (Editor) Oxford University Press. 2005. ISBN 0195170555

- ^ Asante, Molefi Kete. Afrocentricity, Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1988.

- ^ a b c S.O.Y. Keita (1995). "Studies and Comments on Ancient Egyptian Biological Relationships" (PDF). doi:10.1007/BF02444602.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ General history of Africa, by G. Mokhtar, International Scientific Committee for the Drafting of a General History of Africa, Unesco

- ^ Afrocentrism, by Stephen Howe

- ^ Finally in Africa? Egypt, from Diop to Celenko

- ^ a b Ancient Egyptian Origins

- ^ Finally in Africa? Egypt, from Diop to Celenko

- ^ S.O.Y Keita & A.J. Boyce: "The Geographical Origins and Population Relationships of Early Ancient Egyptians", Egypt in Africa, (1996), pp. 25-27

- ^ http://www.egyptologyonline.com/book_of_gates.htm

- ^ http://www.sacred-texts.com/egy/gate/gate20.htm

- ^ http://www.ancientegyptonline.co.uk/bookgates5.html

- ^ Charlotte Booth,The Ancient Egyptians for Dummies (2007) p. 217

- ^ Biological and Ethnic Identity in New Kingdom Nubia

- ^ a b Shavit 2001: 148

- ^ Kemp, Barry J. Ancient Egypt: Anatomy Of A Civilization. Routledge. p. 21. ISBN 978-0415063463.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Aboubacry Moussa Lam, "L'Égypte ancienne et l'Afrique", in Maria R. Turano et Paul Vandepitte, Pour une histoire de l'Afrique, 2003, pp. 50 &51

- ^ Bard, Kathryn A. "Ancient Egyptians and the Issue of Race". in Lefkowitz and MacLean rogers, p. 114

- ^ Raymond Faulkner, A Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian, Oxford: Griffith Institute, 2002, p. 286.

- ^ http://www.egyptologyonline.com/book_of_gates.htm

- ^ http://www.sacred-texts.com/egy/gate/gate20.htm

- ^ http://www.ancientegyptonline.co.uk/bookgates5.html

- ^ Ethiopia.

- ^ A short history of the Egyptian people.

- ^ White, Jon Manchip., Ancient Egypt: Its Culture and History (Dover Publications; New Ed edition, June 1, 1970), p. 141. "It may be noted that the ancient Egyptians themselves appear to have been convinced that their place of origin was African rather than Asian. They made continued reference to the land of Punt as their homeland."

- ^ Short History of the Egyptian People, by E. A. Wallis Budge

- ^ The Genesis of Israel and Egypt, by Emmet John Sweeney

- ^ Dimitri Meeks - Chapter 4 - “Locating Punt” from the book “Mysterious Lands”, by David B. O'Connor and Stephen Quirke.

- ^ http://books.google.com/books?id=jcpQqkHr328C&printsec=frontcover#PPA13,M1

- ^ Hatshepsut's Temple at Deir El Bahari By Frederick Monderson

- ^ Shaw & Nicholson, p.231.

- ^ Tyldesley, Hatchepsut, p.147

- ^ http://weekly.ahram.org.eg/2003/649/he1.htm

- ^ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/483652/Punt

- ^ The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, Ian Shaw, p. 317, 2003

- ^ Building Bridges to Afrocentrism

- ^ Manley Bill, The Penguin Hisorical Atlas to Ancient Egypt (1996), p.83

- ^ Shaw. "The racial and ethnic identity of the Egyptians". The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. ISBN 0192802933.

- ^ http://allaboutegypt.org/tag/zahi-hawass/

- ^ "Ancient Egypt: Hairstyles," Oxford University Press Online[www.oup.com/us/pdf/ancient.egypt/hairstyles.pdf]

- ^ Egypt, Child of Africa. 1994. ISBN 1560007923.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Frank Yurco, "An Egyptological Review" in Mary R. Lefkowitz and Guy MacLean Rogers, eds. Black Athena Revisited. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996. p. 62-100

- ^ Josef Eiwanger: Merimde Beni-salame, In: Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Compiled and edited by Kathryn A. Bard. London/New York 1999, p. 501-505

- ^ Jürgen Seeher. Ma'adi and Wadi Digla. in: Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Compiled and edited by Kathryn A. Bard. London/New York 1999, 455-458

- ^ Zakrzewski, Sonia (2007). "Population continuity or population change: Formation of the ancient Egyptian state" (PDF). doi:10.1002/ajpa.20569.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt By Kathryn A. Bard, Steven Blake Shubert pp 278-279

- ^ S.O.Y. Keita & A. J. Boyce (2005). "Genetics, Egypt, and History: Interpreting Geographical Patterns of Y Chromosome Variation" (PDF). doi:10.1353/hia.2005.0013.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Shomarka Keita (2005). "Y-Chromosome Variation in Egypt" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Text "10.1007/s10437-005-4189-4" ignored (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Keita (2005). "History in the Interpretation of the Pattern of p49a,f TaqI RFLP Y-Chromosome Variation in Egypt" (PDF). doi:10.1002/ajhb.20428.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Shomarka Keita: What genetics can tell us

- ^ Paabo, S., and A. Di Rienzo, A molecular approach to the study of Egyptian history. In Biological Anthropology and the Study of Ancient Egypt. V. Davies and R. Walker, eds. pp. 86-90. London: British Museum Press. 1993

- ^ S.O.Y. Keita & A. J. Boyce. Egypt in Africa, (1996), pp. 25-27

- ^ Cavalli-Sforza, History and Geography of Human Genes, The intermediacy of North Africa and to lesser extent East Africa between Africa and Europe is apparent

- ^ a b Cavalli-Sforza, L.L., P. Menozzi, and A. Piazza. 1994. The History and Geography of Human Genes. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Bosch, E. et al. 1997. Population history of north Africa: evidence from classical genetic markers. Human Biology. 69(3):295-311.

- ^ Arredi B, Poloni E, Paracchini S, Zerjal T, Fathallah D, Makrelouf M, Pascali V, Novelletto A, Tyler-Smith C (2004). "A predominantly neolithic origin for Y-chromosomal DNA variation in North Africa". Am J Hum Genet. 75 (2): 338–45. doi:10.1086/423147. PMID 15202071.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Manni F, Leonardi P, Barakat A, Rouba H, Heyer E, Klintschar M, McElreavey K, Quintana-Murci L (2002). "Y-chromosome analysis in Egypt suggests a genetic regional continuity in Northeastern Africa". Hum Biol. 74 (5): 645–58. doi:10.1353/hub.2002.0054. PMID 12495079.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cavalli-Sforza. "Synthetic maps of Africa". The History and Geography of Human Genes.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)The present population of the Sahara is Caucasoid in the extreme north, with a fairly gradual increase of Negroid component as one goes south - ^ a b Krings. "mtDNA Analysis of Nile River Valley Populations: Genetic Corridor or a Barrier to Migration?" (PDF). PMID PMC1377841.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmid=value (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Kivisild T, Reidla M, Metspalu E, Rosa A, Brehm A, Pennarun E, Parik J, Geberhiwot T, Usanga E, Villems R (2004). "Ethiopian mitochondrial DNA heritage: tracking gene flow across and around the gate of tears". Am J Hum Genet. 75 (5): 752–70. doi:10.1086/425161. PMID 15457403.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stevanovitch (2004). "Mitochondrial DNA Sequence Diversity in a Sedentary Population from Egypt". doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2003.00057.x.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Lucotte (2001). "Brief communication: Y-chromosome haplotypes in Egypt" (PDF). doi:10.1002/ajpa.10190.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Hassan (2008). "Y-Chromosome Variation Among Sudanese:Restricted Gene Flow, Concordance With Language, Geography, and History" (PDF). doi:10.1002/ajpa.20876.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Boas, “Changes in Bodily Form of Descendants of Immigrants” (American Anthropologist 14:530–562, 1912)

- ^ http://www.anthro.fsu.edu/people/faculty/CG_pubs/gravlee03b.pdf

- ^ Clarence C. Gravlee, H. Russell Bernard, and William R. Leonard find in “Heredity, Environment, and Cranial Form: A Re-Analysis of Boas’s Immigrant Data” (American Anthropologist 105[1]:123–136, 2003)

- ^ Kemp, Barry (2005). "Who were the Ancient Egyptians". Egypt: Anatomy of a civilization. p. 52.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Nancy C. Lovell, " Egyptians, physical anthropology of," in Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt, ed. Kathryn A. Bard and Steven Blake Shubert, ( London and New York: Routledge, 1999). pp 328-332)

- ^ Frank Yurco, "An Egyptological Review" in Mary R. Lefkowitz and Guy MacLean Rogers, eds. Black Athena Revisited. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996. p. 62-100

- ^ S.O.Y. Keita (2005). "Early Nile Valley Farmers, From El-Badari, Aboriginals or "European" Agro-Nostratic Immigrants? Craniometric Affinities Considered With Other Data" (PDF). doi:10.1177/0021934704265912.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ http://wysinger.homestead.com/zakrzewski_2007.pdf

- ^ Brace et al., 'Clines and clusters versus "race"' (1993)

- ^ S.O.Y. Keita and Rick A. Kittles (1997). "The Persistence of Racial Thinking and the Myth of Racial Divergence" (PDF). doi:10.1525/aa.1997.99.3.534.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Keita, S.O.Y. "Temporal Variation in Phenetic Affinity of Early Upper Egyptian Male Cranial Series", Human Biology, Volume 80, Number 2 (2008)

- ^ Brace CL, Tracer DP, Yaroch LA, Robb J, Brandt K, Nelson AR (1993). Clines and clusters versus "race:" a test in ancient Egypt and the case of a death on the Nile. Yrbk Phys Anthropol 36:1–31'.

- ^ Predynastic egyptian stature and physical proportions - Robins, Gay. Human Evolution, Volume 1, Number 4 / August, 1986

- ^ S.O.Y. Keita. Studies and Comments of Ancient Egyptian Biological Relationships". History in Africa, 20: 129-154 (1993)

- ^ Gallagher et al. "Population continuity, demic diffusion and Neolithic origins in central-southern Germany: The evidence from body proportions.", Homo. Mar 3 (2009)

- ^ Zakrzewski (2003). "Variation in Ancient Egyptian Stature and Body Proportions" (PDF). doi:10.1002/ajpa.10223.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ S.O.Y. Keita, History in Africa, 20: 129-154 (1993)

- ^ Raxter et al. "Stature estimation in ancient Egyptians: A new technique based on anatomical reconstruction of stature (2008).

- ^ Irish pp. 10-11

- ^ David O'Connor, Ancient Egypt in Africa, (Cavendish Publishing: 2003), p.96

- ^ Ehret (2004). "The Origins of Afroasiatic" (PDF). doi:10.1126/science.306.5702.1680c.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Richard Peet, Elaine Hartwick, Theories of Development, Second Edition: Contentions, Arguments, Alternatives, (Guilford Press: 2009), p.133

- ^ Christopher Ehret: "Ancient Egyptian as an African Language, Egypt as an African Culture", Egypt in Africa (1996), pp. 23-24

- ^ Christopher Ehret: "Ancient Egyptian as an African Language, Egypt as an African Culture", Egypt in Africa (1996), pp. 23-24

- ^ Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization, pp 75

- ^ Théophile Obenga, Origine commune de l'égyptien ancien, du copte et des langues négro-africaines modernes. Introduction à la linguistique historique africaine, Paris: L'Harmattan, 1993, pp. 9-10

- ^ Hoffman. "Egypt before the pharaohs: the prehistoric foundations of Egyptian civilization", pp267

- ^ Redford, Egypt, Israel, p. 17.

- ^ Edwin C. M et. al, "Egypt and the Levant", pp514

- ^ Toby A.H. Wilkinson. " Early Dynastic Egypt: Strategies, Society and Security", pp.15

- ^ Hunting for the Elusive Nubian A-Group People - by Maria Gatto, archaeology.org

- ^ Egypt and Sub-Saharan Africa: Their Interaction - Encyclopedia of Precolonial Africa, by Joseph O. Vogel, AltaMira Press, (1997), pp. 465-472

- ^ Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 46, No. 1 (Jan., 1987), pp. 15-26

- ^ Tracy L. Prowse, Nancy C. Lovell. Concordance of cranial and dental morphological traits and evidence for endogamy in ancient Egypt, American Journal of Physical Anthropology, Vol. 101, Issue 2, October 1996, Pages: 237-246

- ^ Wegner, J. W. 1996. Interaction between the Nubian A-Group and Predynastic Egypt: The Significance of the Qustul Incense Burner. In T. Celenko, Ed., Egypt in Africa: 98-100. Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art/Indiana University Press.

- ^ Genesis of the Pharaohs: Genesis of the ‘Ka’ and Crowns? - Review by Timothy Kendall, American Archaeologist

- ^ http://www.comp-archaeology.org/WendorfSAA98.html

- ^ Ancient Astronomy in Africa

- ^ Wendorf, Fred (2001). Holocene Settlement of the Egyptian Sahara. p. 525. ISBN 0306466120.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help) - ^ Snowden pp.120-121 of Black Athena Revisited.

- ^ Constantin-François Chassebœuf saw the Sphinx as "typically negro in all its features"; Volney, Constantin-François de Chasseboeuf, Voyage en Egypte et en Syrie, Paris, 1825, page 65

- ^ "...its head is grey, ears very large and protruding like a negro’s...the fact that the nose is missing increases the flat, negroid effect. Besides, it was certainly Ethiopian; the lips are thick.." Flaubert, Gustave. Flaubert in Egypt, ed. Francis Steegmuller. (London: Penguin Classics, 1996). ISBN 9780140435825.

- ^ Du Bois, William Edward Burghardt (1915). The Negro. (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1915).

- ^ Hassan, Selim (1949). The Sphinx: Its history in the light of recent excavations. Cairo: Government Press, 1949.

- ^ Abstract Sheldon Peck, Department of Orthodontics at Harvard

- ^ To the Editor (1992-07-18). "Sphinx May Really Be a Black African". Retrieved 2007-10-18.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help); Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ http://www.ianlawton.com/as2.htm

- ^ King Tut Not Black Enough, Protesters Say

- ^ "discovery reconstruction".

- ^ Science museum images

- ^ King Tut's New Face: Behind the Forensic Reconstruction

- ^ Washington Post: A New Look at King Tut

- ^ Skull Indices in a Population Collected From Computed Tomographic Scans of Patients with Head Trauma.

- ^ http://www.guardians.net/hawass/Press_Release_05-05_Tut_Reconstruction.htm

- ^ http://www.thedailynewsegypt.com/article.aspx?ArticleID=9519

- ^ Mike Boehm Eternal Egypt is his business, Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, Calif.: Jun 20, 2005

- ^ Ancient Egypt Magazine, Issue 44, October / November 2007, Meeting Tutankhamun. AFP (Ancient Egypt Magazine). [1] Ancient Egypt Magazine, Issue 44, October / November 2007

- ^ Tutankhamun: beneath the mask

- ^ Egypt: Land of the Pharaohs, Time-Life books, Alexandria, VA 1992 p.8

- ^ Smith, G. Elliot and Dawson, Warren R. - Egyptian Mummies, London, George Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1924 p.99

- ^ Were the Ancient Egyptians Black or White

- ^ Nicholas Reeves and Richard Wilkinson, The Complete Valley of the Kings, 1997, p. 143

- ^ Spindler et al. "Human Mummies: A Global Survey of Their Status and the Techniques of Conservation", Springer, 1996, P43

- ^ Tyldesley. "Ramesses: Egypt's greatest pharaoh" (2000), pg 15

- ^ The Life of Ramses the Great - Egyptology Online, Retrieved April 21, 2009

- ^ http://www.touregypt.net/featurestories/ramesses2intro.htm

- ^ http://www.wellesley.edu/CS/Mary/contents.html

- ^ http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/middle_east/article5908494.ece

- ^ Cleopatra's mother 'was African' - BBC (2009)

- ^ http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk/tol/arts_and_entertainment/tv_and_radio/article5931845.ece

- ^ http://insidecatholic.com/Joomla/index.php?option=com_myblog&show=The-BBC-invents-its-own-Cleopatra..html&Itemid=102

- ^ http://rogueclassicism.com/2009/03/15/cleopatra-arsinoe-and-the-implications/

- ^ http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk/tol/arts_and_entertainment/tv_and_radio/article5931845.ece

- ^ http://insidecatholic.com/Joomla/index.php?option=com_myblog&show=The-BBC-invents-its-own-Cleopatra..html&Itemid=102

- ^ http://www.anthro.fsu.edu/people/faculty/CG_pubs/gravlee03b.pdf

- ^ Clarence C. Gravlee, H. Russell Bernard, and William R. Leonard find in “Heredity, Environment, and Cranial Form: A Re-Analysis of Boas’s Immigrant Data” (American Anthropologist 105[1]:123–136, 2003)

- ^ ”The Lives of Cleopatra and Octavia”, By Sarah Fielding, Christopher D. Johnson, pg154, Bucknell University Press, ISBN 0838752578, 9780838752579

References

- Mary R. Lefkowitz: "Ancient History, Modern Myths", originally printed in The New Republic, 1992. Reprinted with revisions as part of the essay collection Black Athena Revisited, 1996.

- Kathryn A. Bard: "Ancient Egyptians and the issue of Race", Bostonia Magazine, 1992: later part of Black Athena Revisited, 1996.

- Frank M. Snowden, Jr.: "Bernal's "Blacks" and the Afrocentrists", Black Athena Revisited, 1996.

- Joyce Tyldesley: "Cleopatra, Last Queen of Egypt", Profile Books Ltd, 2008.

- Alain Froment, 1994. "Race et Histoire: La recomposition ideologique de l'image des Egyptiens anciens." Journal des Africanistes 64:37-64. available online: Race et Histoire Template:Fr icon

- Yaacov Shavit, 2001: History in Black. African-Americans in Search of an Ancient Past, Frank Cass Publishers

- Shomarka Keita: "The Geographical Origins and Population Relationships of Early Ancient Egyptians", S.O.Y. Keita & A. J. Boyce. Egypt in Africa, pp. 25–27 (1996)

- Aaron Kamugisha: "Finally in Africa? Egypt, from Diop to Celenko", Race & Class, Vol. 45, No. 1, 31-60 (2003) available online: Finally in Africa

- Richard Poe: “Black, White or Biologically African?” Black Spark, White Fire: Did African Explorers Civilize Ancient Europe? pp. 466–471 (1998)

![Maiherpri, a high-ranking official buried in the Valley of the Kings[55]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b6/Maherperi.JPG/64px-Maherperi.JPG)

![Akhenaten, confirmed to have been Tutankhamun's father [56] Cairo Museum.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e5/PortraitStudyOfAkhenaten-ThutmoseWorkshop_EgyptianMuseumBerlin.png/71px-PortraitStudyOfAkhenaten-ThutmoseWorkshop_EgyptianMuseumBerlin.png)