Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Difference between revisions

m Changed protection level of Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Edit warring / content dispute ([Edit=Allow only administrators] (expires 00:31, 26 March 2016 (UTC)) [Move=Allow only administrators] (expires 00:31, 26 M... |

removing a protection template from a non-protected page (info) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{redirect4|ADD|A.D.H.D.}} |

{{redirect4|ADD|A.D.H.D.}} |

||

{{pp-semi-indef}} |

|||

{{bots|deny=Monkbot,Citation bot}} <!-- prevents these bots from editing this page --> |

{{bots|deny=Monkbot,Citation bot}} <!-- prevents these bots from editing this page --> |

||

{{good article}} |

{{good article}} |

||

Revision as of 01:45, 26 March 2016

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | |

|---|---|

| Other names | attention deficit disorder, hyperkinetic disorder (ICD-10) |

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental and mental disorder[1][2] characterized by problems paying attention, excessive activity, or difficulty controlling behavior which is not appropriate for a person's age.[3] These symptoms begin by age six to twelve and persist for more than six months.[4][5] In children problems paying attention may result in poor school performance.[3] Although it causes impairment, particularly in modern society, many children have a good attention span for tasks they find interesting.[6]

Despite being the most commonly studied and diagnosed psychiatric disorder in children and adolescents, the cause is unknown in the majority of cases.[7] The World Health Organization estimated that it affected about 39 million people as of 2013.[8] It affects about 5–7% of children when diagnosed via the DSM-IV criteria[9][10] and 1–2% when diagnosed via the ICD-10 criteria.[11] Rates are similar between countries and depend mostly on how it is diagnosed.[12] ADHD is diagnosed approximately three times more in boys than in girls.[13][14] About 30–50% of people diagnosed in childhood continue to have symptoms into adulthood and between 2–5% of adults have the condition.[15][16][17] The condition can be difficult to tell apart from other disorders as well as from high levels of activity that are still within the normal-range.[5]

ADHD management recommendations vary by country and usually involves some combination of counseling, lifestyle changes, and medications.[3] The British guideline only recommends medications as a first-line treatment in children who have severe symptoms and for them to be considered in those with moderate symptoms who either refuse or fail to improve with counseling.[18] Canadian and American guidelines recommend that medications and behavioral therapy be used together as a first-line therapy, except in preschool-aged children.[19][20] Stimulant therapy is not recommended as a first-line therapy in preschool-aged children in either guideline.[18][20] Treatment with stimulants is effective for up to 14 months; however, its long term effectiveness is unclear.[18][21][22][23] Adolescents and adults tend to develop coping skills which make up for some or all of their impairments.[24]

The medical literature has described symptoms similar to ADHD since the 19th century.[25] ADHD, its diagnosis, and its treatment have been considered controversial since the 1970s.[26] The controversies have involved clinicians, teachers, policymakers, parents, and the media. Topics include ADHD's causes and the use of stimulant medications in its treatment.[27] Most healthcare providers accept ADHD as a genuine disorder, and the debate in the scientific community mainly centers on how it is diagnosed and treated.[28][29][30] The condition was officially known as attention deficit disorder (ADD) from 1980 to 1987 while before this it was known as hyperkinetic reaction of childhood.[31][32]

Signs and symptoms

Inattention, hyperactivity (restlessness in adults), disruptive behavior, and impulsivity are common in ADHD.[33][34] Academic difficulties are frequent as are problems with relationships.[33] The symptoms can be difficult to define as it is hard to draw a line at where normal levels of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity end and significant levels requiring interventions begin.[35]

To be diagnosed per DSM-5, symptoms must be observed in multiple settings for six months or more and to a degree that is much greater than others of the same age.[10] They must also cause problems in the person's social, academic, or work life.[10]

Based on the presenting symptom ADHD can be divided into three subtypes: predominantly inattentive, predominantly hyperactive-impulsive, and combined type.[35]

An individual with inattention may have some or all of the following symptoms:[36]

- Be easily distracted, miss details, forget things, and frequently switch from one activity to another

- Have difficulty maintaining focus on one task

- Become bored with a task after only a few minutes, unless doing something enjoyable

- Have difficulty focusing attention on organizing and completing a task or learning something new

- Have trouble completing or turning in homework assignments, often losing things (e.g., pencils, toys, assignments) needed to complete tasks or activities

- Not seem to listen when spoken to

- Daydream, become easily confused, and move slowly

- Have difficulty processing information as quickly and accurately as others

- Struggle to follow instructions

An individual with hyperactivity may have some or all of the following symptoms:[36]

- Fidget and squirm in their seats

- Talk nonstop

- Dash around, touching or playing with anything and everything in sight

- Have trouble sitting still during dinner, school, doing homework, and story time

- Be constantly in motion

- Have difficulty doing quiet tasks or activities

These hyperactivity symptoms tend to go away with age and turn into "inner restlessness" in teens and adults with ADHD.[15]

An individual with impulsivity may have some or all of the following symptoms:[36]

- Be very impatient

- Blurt out inappropriate comments, show their emotions without restraint, and act without regard for consequences

- Have difficulty waiting for things they want or waiting their turns in games

- Often interrupt conversations or others' activities

People with ADHD more often have difficulties with social skills, such as social interaction and forming and maintaining friendships. This is true for all subtypes. About half of children and adolescents with ADHD experience social rejection by their peers compared to 10–15% of non-ADHD children and adolescents. People with ADHD have attention deficits which cause difficulty processing verbal and nonverbal language which can negatively affect social interaction. They also may drift off during conversations, and miss social cues.[37]

Difficulties managing anger are more common in children with ADHD[38] as are poor handwriting[39] and delays in speech, language and motor development.[40][41] Although it causes significant impairment, particularly in modern society, many children with ADHD have a good attention span for tasks they find interesting.[6]

Associated disorders

In children ADHD occurs with other disorders about ⅔ of the time.[6] Some commonly associated conditions include:

- Learning disabilities have been found to occur in about 20–30% of children with ADHD. Learning disabilities can include developmental speech and language disorders and academic skills disorders.[42] ADHD, however, is not considered a learning disability, but it very frequently causes academic difficulties.[42]

- Tourette syndrome has been found to occur more commonly in the ADHD population.[43]

- Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder (CD), which occur with ADHD in about 50% and 20% of cases respectively.[44] They are characterized by antisocial behaviors such as stubbornness, aggression, frequent temper tantrums, deceitfulness, lying, and stealing.[45] About half of those with hyperactivity and ODD or CD develop antisocial personality disorder in adulthood.[46] Brain imaging supports that conduct disorder and ADHD are separate conditions.[47]

- Primary disorder of vigilance, which is characterized by poor attention and concentration, as well as difficulties staying awake. These children tend to fidget, yawn and stretch and appear to be hyperactive in order to remain alert and active.[45]

- Mood disorders (especially bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder). Boys diagnosed with the combined ADHD subtype are more likely to have a mood disorder.[48] Adults with ADHD sometimes also have bipolar disorder, which requires careful assessment to accurately diagnose and treat both conditions.[49]

- Anxiety disorders have been found to occur more commonly in the ADHD population.[48]

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) can co-occur with ADHD and shares many of its characteristics.[45]

- Substance use disorders. Adolescents and adults with ADHD are at increased risk of developing a substance use problem.[15] This is most commonly seen with alcohol or cannabis.[15] The reason for this may be an altered reward pathway in the brains of ADHD individuals.[15] This makes the evaluation and treatment of ADHD more difficult, with serious substance misuse problems usually treated first due to their greater risks.[18][50]

- Restless legs syndrome has been found to be more common in those with ADHD and is often due to iron deficiency anaemia.[51][52] However, restless legs can simply be a part of ADHD and requires careful assessment to differentiate between the two disorders.[53]

- Sleep disorders and ADHD commonly co-exist. They can also occur as a side effect of medications used to treat ADHD. In children with ADHD, insomnia is the most common sleep disorder with behavioral therapy the preferred treatment.[54][55] Problems with sleep initiation are common among individuals with ADHD but often they will be deep sleepers and have significant difficulty getting up in the morning.[56] Melatonin is sometimes used in children who have sleep onset insomnia.[57]

There is an association with persistent bed wetting,[58] language delay,[59] and developmental coordination disorder (DCD), with about half of people with DCD having ADHD.[60] The language delay in people with ADHD can include problems with auditory processing disorders such as short-term auditory memory weakness, difficulty following instructions, slow speed of processing written and spoken language, difficulties listening in distracting environments e.g. the classroom, and weakness in reading comprehension.[61]

Cause

The cause of most cases of ADHD is unknown; however, it is believed to involve interactions between genetic and environmental factors.[62][63] Certain cases are related to previous infection of or trauma to the brain.[62]

Genetics

Twin studies indicate that the disorder is often inherited from one's parents with genetics determining about 75% of cases.[18][64][65] Siblings of children with ADHD are three to four times more likely to develop the disorder than siblings of children without the disorder.[66] Genetic factors are also believed to be involved in determining whether ADHD persists into adulthood.[67]

Typically, a number of genes are involved, many of which directly affect dopamine neurotransmission.[68][69] Those involved with dopamine include DAT, DRD4, DRD5, TAAR1, MAOA, COMT, and DBH.[69][70][71] Other genes associated with ADHD include SERT, HTR1B, SNAP25, GRIN2A, ADRA2A, TPH2, and BDNF.[68][69] A common variant of a gene called LPHN3 is estimated to be responsible for about 9% of cases and when this variant is present, people are particularly responsive to stimulant medication.[72]

As ADHD is common, natural selection likely favored the traits, at least individually, and they may have provided a survival advantage.[73] For example, some women may be more attracted to males who are risk takers, increasing the frequency of genes that predispose to ADHD in the gene pool.[74] As it is more common in children of anxious or stressed mothers, some argue that ADHD is an adaptation that helps children face a stressful or dangerous environment with, for example, increased impulsivity and exploratory behavior.[75]

Hyperactivity might have been beneficial, from an evolutionary perspective, in situations involving risk, competition, or unpredictable behavior (i.e. exploring new areas or finding new food sources). In these situations, ADHD could have been beneficial to society as a whole even while being harmful to the individual.[74] Additionally, in certain environments it may have offered advantages to the individuals themselves, such as quicker response to predators or superior hunting skills.[76]

People with Down syndrome are more likely to have ADHD.[77]

Environment

Environmental factors are believed to play a lesser role. Alcohol intake during pregnancy can cause fetal alcohol spectrum disorders which can include ADHD or symptoms like it.[78] Exposure to tobacco smoke during pregnancy can cause problems with central nervous system development and can increase the risk of ADHD.[79] Many children exposed to tobacco do not develop ADHD or only have mild symptoms which do not reach the threshold for a diagnosis. A combination of a genetic predisposition with tobacco exposure may explain why some children exposed during pregnancy may develop ADHD and others do not.[80] Children exposed to lead, even low levels, or polychlorinated biphenyls may develop problems which resemble ADHD and fulfill the diagnosis.[81] Exposure to the organophosphate insecticides chlorpyrifos and dialkyl phosphate is associated with an increased risk; however, the evidence is not conclusive.[82]

Very low birth weight, premature birth and early adversity also increase the risk[83] as do infections during pregnancy, at birth, and in early childhood. These infections include, among others, various viruses (measles, varicella, rubella, enterovirus 71) and streptococcal bacterial infection.[84] At least 30% of children with a traumatic brain injury later develop ADHD[85] and about 5% of cases are due to brain damage.[86]

Some children may react negatively to food dyes or preservatives.[87] It is possible that certain food coloring may act as a trigger in those who are genetically predisposed but the evidence is weak.[88]: 452 The United Kingdom and European Union have put in place regulatory measures based on these concerns; the FDA has not.[89]

Society

The diagnosis of ADHD can represent family dysfunction or a poor educational system rather than an individual problem.[90] Some cases may be explained by increasing academic expectations, with a diagnosis being a method for parents in some countries to get extra financial and educational support for their child.[86] The youngest children in a class have been found to be more likely to be diagnosed as having ADHD possibly due to their being developmentally behind their older classmates.[91][92] Behavior typical of ADHD occurs more commonly in children who have experienced violence and emotional abuse.[18]

Per social construction theory it is societies that determine the boundary between normal and abnormal behavior. Members of society, including physicians, parents, and teachers, determine which diagnostic criteria are used and, thus, the number of people affected.[93] This leads to the current situation where the DSM-IV arrives at levels of ADHD three to four times higher than those obtained with the ICD-10.[14] Thomas Szasz, a supporter of this theory, has argued that ADHD was "invented and not discovered."[94][95]

Pathophysiology

Current models of ADHD suggest that it is associated with functional impairments in some of the brain's neurotransmitter systems, particularly those involving dopamine and norepinephrine.[96] The dopamine and norepinephrine pathways that originate in the ventral tegmental area and locus coeruleus project to diverse regions of the brain and govern a variety of cognitive processes.[97] The dopamine pathways and norepinephrine pathways which project to the prefrontal cortex and striatum are directly responsible for modulating executive function (cognitive control of behavior), motivation, reward perception, and motor function;[96][97] these pathways are known to play a central role in the pathophysiology of ADHD.[97][98][99] Larger models of ADHD with additional pathways have been proposed.[96][98][99]

Brain structure

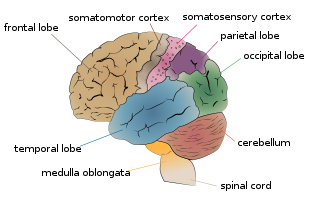

In children with ADHD, there is a general reduction of volume in certain brain structures, with a proportionally greater decrease in the volume in the left-sided prefrontal cortex.[96][100] The posterior parietal cortex also shows thinning in ADHD individuals compared to controls.[96] Other brain structures in the prefrontal-striatal-cerebellar and prefrontal-striatal-thalamic circuits have also been found to differ between people with and without ADHD.[96][98][99]

Neurotransmitter pathways

Previously it was thought that the elevated number of dopamine transporters in people with ADHD was part of the pathophysiology but it appears that the elevated numbers are due to adaptation to exposure to stimulants.[101] Current models involve the mesocorticolimbic dopamine pathway and the locus coeruleus-noradrenergic system.[96][97] ADHD psychostimulants possess treatment efficacy because they increase neurotransmitter activity in these systems.[96][97][102] There may additionally be abnormalities in serotoninergic and cholinergic pathways.[102][103] Neurotransmission of glutamate, a cotransmitter with dopamine in the mesolimbic pathway,[104] seems to be also involved.[105]

Executive function and motivation

ADHD symptoms involve a difficulty with executive functions.[56][97] Executive function refers to a number of mental processes that are required to regulate, control, and manage daily life tasks.[56][97] Some of these impairments include problems with organization, time keeping, excessive procrastination, concentration, processing speed, regulating emotions, and utilizing working memory.[56] People usually have decent long-term memory.[56] The criteria for an executive function deficit are met in 30–50% of children and adolescents with ADHD.[106] One study found that 80% of individuals with ADHD were impaired in at least one executive function task, compared to 50% for individuals without ADHD.[107] Due to the rates of brain maturation and the increasing demands for executive control as a person gets older, ADHD impairments may not fully manifest themselves until adolescence or even early adulthood.[56]

ADHD has also been associated with motivational deficits in children.[108] Children with ADHD find it difficult to focus on long-term over short-term rewards, and exhibit impulsive behavior for short-term rewards.[108] In these individuals, a large amount of positive reinforcement effectively improves task performance.[108] ADHD stimulants may improve persistence in ADHD children as well.[108]

Diagnosis

ADHD is diagnosed by an assessment of a person's childhood behavioral and mental development, including ruling out the effects of drugs, medications and other medical or psychiatric problems as explanations for the symptoms.[18] It often takes into account feedback from parents and teachers[5] with most diagnoses begun after a teacher raises concerns.[86] It may be viewed as the extreme end of one or more continuous human traits found in all people.[18] Whether someone responds to medications does not confirm or rule out the diagnosis. As imaging studies of the brain do not give consistent results between individuals, they are only used for research purposes and not diagnosis.[109]

In North America, the DSM-IV or DSM-5 criteria are often used for diagnosis, while European countries usually use the ICD-10. With the DSM-IV criteria a diagnosis of ADHD is 3–4 times more likely than with the ICD-10 criteria.[14] It is classified as neurodevelopmental psychiatric disorder.[15][2] Additionally, it is classified as a disruptive behavior disorder along with oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, and antisocial personality disorder.[110] A diagnosis does not imply a neurological disorder.[18]

Associated conditions that should be screened for include anxiety, depression, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, and learning and language disorders. Other conditions that should be considered are other neurodevelopmental disorders, tics, and sleep apnea.[111]

Diagnosis of ADHD using quantitative electroencephalography (QEEG) is an ongoing area of investigation, although the value of QEEG in ADHD is currently unclear.[112][113] In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration has approved the use of QEEG to evaluate the morbidity of ADHD.[114]

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

As with many other psychiatric disorders, formal diagnosis is made by a qualified professional based on a set number of criteria. In the United States, these criteria are defined by the American Psychiatric Association in the DSM. Based on the DSM criteria, there are three sub-types of ADHD:[10]

- ADHD predominantly inattentive type (ADHD-PI) presents with symptoms including being easily distracted, forgetful, daydreaming, disorganization, poor concentration, and difficulty completing tasks.[4][10]

- ADHD, predominantly hyperactive-impulsive type presents with excessive fidgetiness and restlessness, hyperactivity, difficulty waiting and remaining seated, immature behavior; destructive behaviors may also be present.[4][10]

- ADHD, combined type is a combination of the first two subtypes.[4][10]

This subdivision is based on presence of at least six out of nine long-term (lasting at least six months) symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity–impulsivity, or both.[115] To be considered, the symptoms must have appeared by the age of six to twelve and occur in more than one environment (e.g. at home and at school or work).[4] The symptoms must be not appropriate for a child of that age[4][116] and there must be evidence that it is causing social, school or work related problems.[115]

Most children with ADHD have the combined type. Children with the inattention subtype are less likely to act out or have difficulties getting along with other children. They may sit quietly, but without paying attention resulting in the child difficulties being overlooked.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2014) |

International Classification of Diseases

In the ICD-10, the symptoms of "hyperkinetic disorder" are analogous to ADHD in the DSM-5. When a conduct disorder (as defined by ICD-10)[40] is present, the condition is referred to as hyperkinetic conduct disorder. Otherwise, the disorder is classified as disturbance of activity and attention, other hyperkinetic disorders or hyperkinetic disorders, unspecified. The latter is sometimes referred to as, hyperkinetic syndrome.[40]

Adults

Adults with ADHD are diagnosed under the same criteria, including that their signs must have been present by the age of six to twelve. Questioning parents or guardians as to how the person behaved and developed as a child may form part of the assessment; a family history of ADHD also adds weight to a diagnosis.[15] While the core symptoms of ADHD are similar in children and adults they often present differently in adults than in children, for example excessive physical activity seen in children may present as feelings of restlessness and constant mental activity in adults.[15]

Differential diagnosis

| ADHD Symptoms which are related to other Disorders[117] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | Anxiety disorder | Bipolar disorder | |

|

|

| |

Symptoms of ADHD such as low mood and poor self-image, mood swings, and irritability can be confused with dysthymia, cyclothymia or bipolar disorder as well as with borderline personality disorder.[15] Some symptoms that are due to anxiety disorders, antisocial personality disorder, developmental disabilities or mental retardation or the effects of substance abuse such as intoxication and withdrawal can overlap with some ADHD. These disorders can also sometimes occur along with ADHD. Medical conditions which can cause ADHD type symptoms include: hyperthyroidism, seizure disorder, lead toxicity, hearing deficits, hepatic disease, sleep apnea, drug interactions, and head injury.[24]

Primary sleep disorders may affect attention and behavior and the symptoms of ADHD may affect sleep.[118] It is thus recommended that children with ADHD be regularly assessed for sleep problems.[119] Sleepiness in children may result in symptoms ranging from the classic ones of yawning and rubbing the eyes, to hyperactivity and inattentiveness.[120] Obstructive sleep apnea can also cause ADHD type symptoms.[120]

Management

The management of ADHD typically involves counseling or medications either alone or in combination. While treatment may improve long-term outcomes, it does not get rid of negative outcomes entirely.[121]

Medications used include stimulants, atomoxetine, alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonists, and sometimes antidepressants.[48][102] Dietary modifications may also be of benefit[122] with evidence supporting free fatty acids and reduced exposure to food coloring.[123] Removing other foods from the diet is not currently supported by the evidence.[123]

Behavioral therapies

There is good evidence for the use of behavioral therapies in ADHD[124] and they are the recommended first line treatment in those who have mild symptoms or are preschool-aged.[125] Psychological therapies used include: psychoeducational input, behavior therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), interpersonal psychotherapy, family therapy, school-based interventions, social skills training, behavioral peer intervention, organization training,[126] parent management training,[18] and neurofeedback.[127] Behavior modification and neurofeedback have the best support.[128]

Parent training and education have been found to have short-term benefits.[129][130] There is little high quality research on the effectiveness of family therapy for ADHD, but the evidence that exists shows that it is similar to community care and better than a placebo.[131] Several ADHD specific support groups exist as informational sources and may help families cope with ADHD.[132]

Training in social skills, behavioral modification and medication may have some limited beneficial effects. The most important factor in reducing later psychological problems, such as major depression, criminality, school failure, and substance use disorders is formation of friendships with people who are not involved in delinquent activities.[133]

Regular physical exercise, particularly aerobic exercise, is an effective add on treatment for ADHD, although the best type and intensity is not currently known.[134][135] In particular, physical exercise has been shown to result in better behavior and motor abilities without causing any side effects.[134][135]

Medication

Stimulant medications are the pharmaceutical treatment of choice.[136][137] They have at least some effect in the short term in about 80% of people.[23] Methylphenidate appears to improve symptoms as reported by teachers and parents.[138]

There are a number of non-stimulant medications, such as atomoxetine, bupropion, guanfacine, and clonidine that may be used as alternatives.[136] There are no good studies comparing the various medications; however, they appear more or less equal with respect to side effects.[139] Stimulants appear to improve academic performance while atomoxetine does not.[140] There is little evidence on their effects on social behaviors.[139] Medications are not recommended for preschool children, as the long-term effects in this age group are not known.[18][141] The long-term effects of stimulants generally are unclear with one study finding benefit, another finding no benefit and a third finding evidence of harm.[142] Magnetic resonance imaging studies suggest that long-term treatment with amphetamine or methylphenidate decreases abnormalities in brain structure and function found in subjects with ADHD.[143][144][145] Atomoxetine, due to its lack of addiction liability, may be preferred in those who are at risk of recreational or compulsive stimulant use.[15] Guidelines on when to use medications vary by country, with the United Kingdom's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommending use only in severe cases, while most United States guidelines recommend medications in most age groups.[19]

While stimulants and atomoxetine are usually safe, there are side-effects and contraindications to their use.[136] A large overdose on ADHD stimulants is commonly associated with symptoms such as stimulant psychosis and mania;[146] although very rare, at therapeutic doses these events appear to occur in approximately 0.1% of individuals within the first several weeks after starting amphetamine or methylphenidate therapy.[147][146][148] Administration of an antipsychotic medication has been found to effectively resolve the symptoms of acute amphetamine psychosis.[146] Regular monitoring has been recommended in those on long-term treatment.[149] Stimulant therapy should be stopped from time to assess for continuing need for medication.[150] Long-term misuse of stimulant medications at doses above the therapeutic range for ADHD treatment is associated with addiction and dependence;[151][152] several studies indicate that untreated ADHD is associated with elevated risk of substance use disorders and conduct disorders.[151] The use of stimulants appears to either reduce this risk or have no effect on it.[15][151] The safety of these medications in pregnancy is unclear.[153] Zinc deficiency has been associated with inattentive symptoms and there is evidence that zinc supplementation can benefit children with ADHD who have low zinc levels.[87] Iron, magnesium and iodine may also have an effect on ADHD symptoms.[154] There is evidence of a modest benefit of omega 3 fatty acid supplementation, but it is not recommended in place of traditional medication.[155]

Prognosis

An 8-year follow up of children diagnosed with ADHD (combined type) found that they often have difficulties in adolescence, regardless of treatment or lack thereof.[156] In the US, fewer than 5% of individuals with ADHD get a college degree,[157] compared to 28% of the general population aged 25 years and older.[158] The proportion of children meeting criteria for ADHD drops by about half in the three years following the diagnosis and this occurs regardless of treatments used.[159][160] ADHD persists into adulthood in about 30–50% of cases.[16] Those affected are likely to develop coping mechanisms as they mature, thus compensating for their previous symptoms.[24]

Epidemiology

ADHD is estimated to affect about 6–7% of people aged 18 and under when diagnosed via the DSM-IV criteria.[9] When diagnosed via the ICD-10 criteria rates in this age group are estimated at 1–2%.[11] Children in North America appear to have a higher rate of ADHD than children in Africa and the Middle East; this is believed to be due to differing methods of diagnosis rather than a difference in underlying frequency.[161] If the same diagnostic methods are used, the rates are more or less the same between countries.[12] It is diagnosed approximately three times more often in boys than in girls.[13][14] This difference between sexes may reflect either a difference in susceptibility or that females with ADHD are less likely to be diagnosed than males.[162]

Rates of diagnosis and treatment have increased in both the United Kingdom and the United States since the 1970s.[163] This is believed to be primarily due to changes in how the condition is diagnosed[163] and how readily people are willing to treat it with medications rather than a true change in how common the condition is.[11] It is believed that changes to the diagnostic criteria in 2013 with the release of the DSM-5 will increase the percentage of people diagnosed with ADHD, especially among adults.[164]

History

Hyperactivity has long been part of the human condition. Sir Alexander Crichton describes "mental restlessness" in his book An inquiry into the nature and origin of mental derangement written in 1798.[165][166] ADHD was first clearly described by George Still in 1902.[163]

The terminology used to describe the condition has changed over time and has included: in the DSM-I (1952) "minimal brain dysfunction", in the DSM-II (1968) "hyperkinetic reaction of childhood", in the DSM-III (1980) "attention-deficit disorder (ADD) with or without hyperactivity".[163] In 1987 this was changed to ADHD in the DSM-III-R and the DSM-IV in 1994 split the diagnosis into three subtypes, ADHD inattentive type, ADHD hyperactive-impulsive type and ADHD combined type.[167] These terms were kept in the DSM-5 in 2013.[10] Other terms have included "minimal brain damage" used in the 1930s.[168]

The use of stimulants to treat ADHD was first described in 1937.[169] In 1934, Benzedrine became the first amphetamine medication approved for use in the United States.[170] Methylphenidate was introduced in the 1950s, and enantiopure dextroamphetamine in the 1970s.[163]

Society and culture

Controversies

ADHD, its diagnosis, and its treatment have been controversial since the 1970s.[26][27][171] The controversies involve clinicians, teachers, policymakers, parents, and the media. Positions range from the view that ADHD is within the normal range of behavior[18][172] to the hypothesis that ADHD is a genetic condition.[173] Other areas of controversy include the use of stimulant medications in children,[27][174] the method of diagnosis, and the possibility of overdiagnosis.[174] In 2012, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, while acknowledging the controversy, states that the current treatments and methods of diagnosis are based on the dominant view of the academic literature.[18] In 2014, Keith Conners, one of the early advocates for recognition of the disorder, spoke out against overdiagnosis in a New York Times article.[175] In contrast, a 2014 peer-reviewed medical literature review indicated that ADHD is underdiagnosed in adults.[17]

With widely differing rates of diagnosis across countries, states within countries, races, and ethnicities, some suspect factors other than the presence of the symptoms of ADHD are playing a role in diagnosis.[91] Some sociologists consider ADHD to be an example of the medicalization of deviant behavior, that is, the turning of the previously non-medical issue of school performance into a medical one.[26][86] Most healthcare providers accept ADHD as a genuine disorder, at least in the small number of people with severe symptoms.[86] Among healthcare providers the debate mainly centers on diagnosis and treatment in the much larger number of people with less severe symptoms.[29][30][86]

As of 2009[update], 8% of all United States Major League Baseball players had been diagnosed with ADHD, making the disorder common among this population. The increase coincided with the League's 2006 ban on stimulants, which has raised concern that some players are mimicking or falsifying the symptoms or history of ADHD to get around the ban on the use of stimulants in sport.[176]

Media commentary

A number of public figures have given controversial statements regarding ADHD. Tom Cruise has described the medications Ritalin (methylphenidate) and Adderall (an amphetamine formulation) as "street drugs".[177] Ushma S. Neill criticized this view, stating that the doses of stimulants used in the treatment of ADHD do not cause addiction and that there is some evidence of a reduced risk of later substance addiction in children treated with stimulants.[178] In the UK, Susan Greenfield spoke out publicly in 2007 in the House of Lords about the need for a wide-ranging inquiry into the dramatic increase in the diagnosis of ADHD, and possible causes. Her comments followed a BBC Panorama program that highlighted research that suggested medications are no better than other forms of therapy in the long term.[179] In 2010, the BBC Trust criticized the 2007 Panorama program for summarizing the research as showing "no demonstrable improvement in children's behaviour after staying on ADHD medication for three years" when in actuality "the study found that medication did offer a significant improvement over time" although the long-term benefits of medication were found to be "no better than children who were treated with behavior therapy."[180]

Special populations

Adults

It is estimated that between 2–5% of adults have ADHD.[15] Around 25[15]-50[10]% of children with ADHD continue to experience ADHD symptoms into adulthood, while the rest experiences fewer or no symptoms. Most adults remain untreated.[181] Many have a disorganized life and use non-prescribed drugs or alcohol as a coping mechanism.[24] Other problems may include relationship and job difficulties, and an increased risk of criminal activities.[15] Associated mental health problems include: depression, anxiety disorder, and learning disabilities.[24]

Some ADHD symptoms in adults differ from those seen in children. While children with ADHD may climb and run about excessively, adults may experience an inability to relax, or they talk excessively in social situations. Adults with ADHD may start relationships impulsively, display sensation-seeking behavior, and be short-tempered. Addictive behavior such as substance abuse and gambling are common. The DSM-IV criteria have been criticized for not being appropriate for adults; those who present differently may lead to the claim that they outgrew the diagnosis.[15]

Children with high IQ scores

The diagnosis of ADHD and the significance of its impact on children with a high intelligence quotient (IQ) is controversial. Most studies have found similar impairments regardless of IQ, with higher rates of repeating grades and having social difficulties. Additionally, more than half of people with high IQ and ADHD experience major depressive disorder or oppositional defiant disorder at some point in their lives. Generalised anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder and social phobia are also more common. There is some evidence that individuals with high IQ and ADHD have a lowered risk of substance abuse and anti-social behavior compared to children with low and average IQ and ADHD. Children and adolescents with high IQ can have their level of intelligence mismeasured during a standard evaluation and may require more comprehensive testing.[182]

References

- ^ Sroubek, A; Kelly, M; Li, X (February 2013). "Inattentiveness in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Neuroscience Bulletin. 29 (1): 103–10. doi:10.1007/s12264-012-1295-6. PMID 23299717.

- ^ a b Caroline, SC, ed. (2010). Encyclopedia of Cross-Cultural School Psychology. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 133. ISBN 9780387717982.

- ^ a b c "Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder". National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f "Symptoms and Diagnosis". Attention-Deficit / Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Division of Human Development, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 29 September 2014. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- ^ a b c Dulcan, MK; Lake, MB (2011). Concise Guide to Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (4th illustrated ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing. p. 34. ISBN 9781585624164.

- ^ a b c Walitza, S; Drechsler, R; Ball, J (August 2012). "Das schulkind mit ADHS" [The school child with ADHD]. Ther Umsch (in German). 69 (8): 467–73. doi:10.1024/0040-5930/a000316. PMID 22851461.

- ^ "Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (Easy-to-Read)". National Institute of Mental Health. 2013. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ^ Global Burden of Disease Study 2013, Collaborators (5 June 2015). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet (London, England). doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4. PMID 26063472.

{{cite journal}}:|first1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Willcutt, EG (July 2012). "The prevalence of DSM-IV attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analytic review". Neurotherapeutics. 9 (3): 490–9. doi:10.1007/s13311-012-0135-8. PMC 3441936. PMID 22976615.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing. pp. 59–65. ISBN 0890425558.

- ^ a b c Cowen, P; Harrison, P; Burns, T (2012). Shorter Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry (6th ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 546. ISBN 9780199605613.

- ^ a b Faraone, SV (2011). "Ch. 25: Epidemiology of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder". In Tsuang, MT; Tohen, M; Jones, P (eds.). Textbook of Psychiatric Epidemiology (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 450. ISBN 9780470977408.

- ^ a b Emond, V; Joyal, C; Poissant, H (April 2009). "Neuroanatomie structurelle et fonctionnelle du trouble déficitaire d'attention avec ou sans hyperactivité (TDAH)" [Structural and functional neuroanatomy of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)]. Encephale (in French). 35 (2): 107–14. doi:10.1016/j.encep.2008.01.005. PMID 19393378.

- ^ a b c d Singh, I (December 2008). "Beyond polemics: Science and ethics of ADHD". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 9 (12): 957–64. doi:10.1038/nrn2514. PMID 19020513.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Kooij, SJ; Bejerot, S; Blackwell, A; Caci, H; Casas-Brugué, M; Carpentier, PJ; Edvinsson, D; Fayyad, J; Foeken, K; Fitzgerald, M; Gaillac, V; Ginsberg, Y; Henry, C; Krause, J; Lensing, MB; Manor, I; Niederhofer, H; Nunes-Filipe, C; Ohlmeier, MD; Oswald, P; Pallanti, S; Pehlivanidis, A; Ramos-Quiroga, JA; Rastam, M; Ryffel-Rawak, D; Stes, S; Asherson, P (2010). "European consensus statement on diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD: The European Network Adult ADHD". BMC Psychiatry. 10: 67. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-10-67. PMC 2942810. PMID 20815868.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Bálint, S; Czobor, P; Mészáros, A; Simon, V; Bitter, I (2008). "Neuropszichológiai károsodásokat felnőtt figyelemhiányos hiperaktivitás zavar(ADHD): A szakirodalmi áttekintés" [Neuropsychological impairments in adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A literature review]. Psychiatria Hungarica (in Hungarian). 23 (5): 324–335. PMID 19129549.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Underdiagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adult patients: a review of the literature". Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 16 (3). 2014. doi:10.4088/PCC.13r01600. PMC 4195639. PMID 25317367.

Reports indicate that ADHD affects 2.5%–5% of adults in the general population,5–8 compared with 5%–7% of children.9,10 ... However, fewer than 20% of adults with ADHD are currently diagnosed and/or treated by psychiatrists.7,15,16

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (2009). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Diagnosis and Management of ADHD in Children, Young People and Adults. British Psychological Society. pp. 19–27, 38, 130, 133, 317. ISBN 9781854334718.

- ^ a b "Canadian ADHD Practice Guidelines" (PDF). Canadian ADHD Alliance. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ a b "Attention-Deficit / Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Recommendations". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 24 June 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ Huang, YS; Tsai, MH (July 2011). "Long-term outcomes with medications for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: Current status of knowledge". CNS Drugs. 25 (7): 539–554. doi:10.2165/11589380-000000000-00000. PMID 21699268.

- ^ Arnold, LE; Hodgkins, P; Caci, H; Kahle, J; Young, S (February 2015). "Effect of treatment modality on long-term outcomes in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review". PLoS ONE. 10 (2): e0116407. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0116407. PMC 4340791. PMID 25714373.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b "The long-term outcomes of interventions for the management of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials". Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 6: 87–99. September 2013. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S49114. PMC 3785407. PMID 24082796.

Results suggest there is moderate-to-high-level evidence that combined pharmacological and behavioral interventions, and pharmacological interventions alone can be effective in managing the core ADHD symptoms and academic performance at 14 months. However, the effect size may decrease beyond this period. ... Only one paper53 examining outcomes beyond 36 months met the review criteria. ... There is high level evidence suggesting that pharmacological treatment can have a major beneficial effect on the core symptoms of ADHD (hyperactivity, inattention, and impulsivity) in approximately 80% of cases compared with placebo controls, in the short term.22

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d e Gentile JP, Atiq R, Gillig PM (August 2006). "Adult ADHD: Diagnosis, Differential Diagnosis, and Medication Management". Psychiatry (Edgmont). 3 (8): 25–30. PMC 2957278. PMID 20963192.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lange, KW; Reichl, S; Lange, KM; Tucha, L; Tucha, O (December 2010). "The history of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder". ADHD Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders. 2 (4): 241–55. doi:10.1007/s12402-010-0045-8. PMC 3000907. PMID 21258430.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help)

- ^ a b c Parrillo VN (2008). Encyclopedia of Social Problems. SAGE. p. 63. ISBN 9781412941655. Retrieved 2 May 2009.

- ^ a b c Mayes R, Bagwell C, Erkulwater J (2008). "ADHD and the rise in stimulant use among children". Harv Rev Psychiatry. 16 (3): 151–166. doi:10.1080/10673220802167782. PMID 18569037.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sim MG, Hulse G, Khong E (August 2004). "When the child with ADHD grows up" (PDF). Aust Fam Physician. 33 (8): 615–618. PMID 15373378. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Silver LB (2004). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (3rd ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing. pp. 4–7. ISBN 9781585621316.

- ^ a b Schonwald A, Lechner E (April 2006). "Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: complexities and controversies". Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 18 (2): 189–195. doi:10.1097/01.mop.0000193302.70882.70. PMID 16601502.

- ^ Weiss, Lawrence G. (2005). WISC-IV clinical use and interpretation scientist-practitioner perspectives (1st ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic Press. p. 237. ISBN 9780125649315.

- ^ "ADHD: The Diagnostic Criteria". PBS. Frontline. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ^ a b Dobie C (2012). "Diagnosis and management of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in primary care for school-age children and adolescents". Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement: 79.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Facts About ADHD". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ^ a b Ramsay JR (2007). Cognitive behavioral therapy for adult ADHD. Routledge. pp. 4, 25–26. ISBN 0415955017.

- ^ a b c National Institute of Mental Health (2008). "Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)". National Institutes of Health.

- ^ Coleman WL (August 2008). "Social competence and friendship formation in adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Adolesc Med State Art Rev. 19 (2): 278–99, x. PMID 18822833.

- ^ "ADHD Anger Management Directory". Webmd.com. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ^ Racine MB, Majnemer A, Shevell M, Snider L (April 2008). "Handwriting performance in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)". J. Child Neurol. 23 (4): 399–406. doi:10.1177/0883073807309244. PMID 18401033.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "F90 Hyperkinetic disorders", International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision, World Health Organisation, 2010, retrieved 2 November 2014

- ^ Bellani M, Moretti A, Perlini C, Brambilla P (December 2011). "Language disturbances in ADHD". Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 20 (4): 311–315. doi:10.1017/S2045796011000527. PMID 22201208.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Bailey, Eileen. "ADHD and Learning Disabilities: How can you help your child cope with ADHD and subsequent Learning Difficulties? There is a way". Remedy Health Media, LLC. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ^ "Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)". The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ^ McBurnett, K; Pfiffner, LJ (November 2009). "Treatment of aggressive ADHD in children and adolescents: Conceptualization and treatment of comorbid behavior disorders". Postgrad Med. 121 (6): 158–165. doi:10.3810/pgm.2009.11.2084. PMID 19940426.

- ^ a b c Krull, KR (5 December 2007). "Evaluation and diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children". Uptodate. Wolters Kluwer Health. Retrieved 12 September 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ Hofvander B, Ossowski D, Lundström S, Anckarsäter H (2009). "Continuity of aggressive antisocial behavior from childhood to adulthood: The question of phenotype definition". Int J Law Psychiatry. 32 (4): 224–234. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2009.04.004. PMID 19428109.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rubia K (June 2011). ""Cool" inferior frontostriatal dysfunction in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder versus "hot" ventromedial orbitofrontal-limbic dysfunction in conduct disorder: a review". Biol. Psychiatry. 69 (12): e69–87. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.023. PMID 21094938.

- ^ a b c Wilens TE, Spencer TJ (September 2010). "Understanding attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder from childhood to adulthood". Postgrad Med. 122 (5): 97–109. doi:10.3810/pgm.2010.09.2206. PMC 3724232. PMID 20861593.

- ^ Baud P, Perroud N, Aubry JM (June 2011). "[Bipolar disorder and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults: differential diagnosis or comorbidity]". Rev Med Suisse (in French). 7 (297): 1219–1222. PMID 21717696.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wilens TE, Morrison NR (July 2011). "The intersection of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and substance abuse". Curr Opin Psychiatry. 24 (4): 280–285. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e328345c956. PMC 3435098. PMID 21483267.

- ^ Merino-Andreu M (March 2011). "Trastorno por déficit de atención/hiperactividad y síndrome de piernas inquietas en niños". Rev Neurol (in Spanish). 52 Suppl 1: S85–95. PMID 21365608.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Picchietti MA, Picchietti DL (August 2010). "Advances in pediatric restless legs syndrome: Iron, genetics, diagnosis and treatment". Sleep Med. 11 (7): 643–651. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2009.11.014. PMID 20620105.

- ^ Karroum E, Konofal E, Arnulf I (2008). "Restless-legs syndrome". Rev. Neurol. (Paris) (in French). 164 (8–9): 701–721. doi:10.1016/j.neurol.2008.06.006. PMID 18656214.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Corkum P, Davidson F, Macpherson M (June 2011). "A framework for the assessment and treatment of sleep problems in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 58 (3): 667–683. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2011.03.004. PMID 21600348.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tsai MH, Huang YS (May 2010). "Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and sleep disorders in children". Med. Clin. North Am. 94 (3): 615–632. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2010.03.008. PMID 20451036.

- ^ a b c d e f Brown TE (October 2008). "ADD/ADHD and Impaired Executive Function in Clinical Practice". Curr Psychiatry Rep. 10 (5): 407–411. doi:10.1007/s11920-008-0065-7. PMID 18803914.

- ^ Bendz LM, Scates AC (January 2010). "Melatonin treatment for insomnia in pediatric patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 44 (1): 185–191. doi:10.1345/aph.1M365. PMID 20028959.

- ^ Shreeram S, He JP, Kalaydjian A, Brothers S, Merikangas KR (January 2009). "Prevalence of enuresis and its association with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among United States children: results from a nationally representative study". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 48 (1): 35–41. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e318190045c. PMC 2794242. PMID 19096296.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hagberg BS, Miniscalco C, Gillberg C (2010). "Clinic attenders with autism or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: cognitive profile at school age and its relationship to preschool indicators of language delay". Res Dev Disabil. 31 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2009.07.012. PMID 19713073.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fliers EA, Franke B, Buitelaar JK (2011). "[Motor problems in children with ADHD receive too little attention in clinical practice]". Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd (in Dutch and Flemish). 155 (50): A3559. PMID 22186361.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Greathead, Philippa. "Language Disorders and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder ." ADDIS Information Centre. ADDIS, 6 November 2013. Web. 6 November 2013. <http://www.addiss.co.uk/languagedisorders.htm>.

- ^ a b Millichap, J. Gordon (2010). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Handbook a Physician's Guide to ADHD (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Springer Science. p. 26. ISBN 9781441913975. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ^ Thapar A, Cooper M, Eyre O, Langley K (January 2013). "What have we learnt about the causes of ADHD?". J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 54 (1): 3–16. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02611.x. PMC 3572580. PMID 22963644.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Neale BM, Medland SE, Ripke S, Asherson P, Franke B, Lesch KP, Faraone SV, Nguyen TT, Schäfer H, Holmans P, Daly M, Steinhausen HC, Freitag C, Reif A, Renner TJ, Romanos M, Romanos J, Walitza S, Warnke A, Meyer J, Palmason H, Buitelaar J, Vasquez AA, Lambregts-Rommelse N, Gill M, Anney RJ, Langely K, O'Donovan M, Williams N, Owen M, Thapar A, Kent L, Sergeant J, Roeyers H, Mick E, Biederman J, Doyle A, Smalley S, Loo S, Hakonarson H, Elia J, Todorov A, Miranda A, Mulas F, Ebstein RP, Rothenberger A, Banaschewski T, Oades RD, Sonuga-Barke E, McGough J, Nisenbaum L, Middleton F, Hu X, Nelson S (September 2010). "Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 49 (9): 884–897. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2010.06.008. PMC 2928252. PMID 20732625.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Burt SA (July 2009). "Rethinking environmental contributions to child and adolescent psychopathology: a meta-analysis of shared environmental influences". Psychol Bull. 135 (4): 608–637. doi:10.1037/a0015702. PMID 19586164.

- ^ Nolen-Hoeksema S (2013). Abnormal Psychology (Sixth ed.). p. 267. ISBN 9780078035388.

- ^ Franke B, Faraone SV, Asherson P, Buitelaar J, Bau CH, Ramos-Quiroga JA, Mick E, Grevet EH, Johansson S, Haavik J, Lesch KP, Cormand B, Reif A (October 2012). "The genetics of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults, a review". Mol. Psychiatry. 17 (10): 960–987. doi:10.1038/mp.2011.138. PMC 3449233. PMID 22105624.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Gizer IR, Ficks C, Waldman ID (July 2009). "Candidate gene studies of ADHD: a meta-analytic review". Hum. Genet. 126 (1): 51–90. doi:10.1007/s00439-009-0694-x. PMID 19506906.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Kebir O, Tabbane K, Sengupta S, Joober R (March 2009). "Candidate genes and neuropsychological phenotypes in children with ADHD: review of association studies". J Psychiatry Neurosci. 34 (2): 88–101. PMC 2647566. PMID 19270759.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Berry, MD (January 2007). "The potential of trace amines and their receptors for treating neurological and psychiatric diseases". Reviews on recent clinical trials. 2 (1): 3–19. doi:10.2174/157488707779318107. PMID 18473983.

- ^ Sotnikova TD, Caron MG, Gainetdinov RR (August 2009). "Trace amine-associated receptors as emerging therapeutic targets". Mol. Pharmacol. 76 (2): 229–235. doi:10.1124/mol.109.055970. PMC 2713119. PMID 19389919.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Arcos-Burgos M, Muenke M (November 2010). "Toward a better understanding of ADHD: LPHN3 gene variants and the susceptibility to develop ADHD". Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2 (3): 139–147. doi:10.1007/s12402-010-0030-2. PMC 3280610. PMID 21432600.

- ^ Cardo E, Nevot A, Redondo M; et al. (March 2010). "Trastorno por déficit de atención/hiperactividad: ¿un patrón evolutivo?". Rev Neurol (in Spanish). 50 Suppl 3: S143–7. PMID 20200842.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Williams J, Taylor E (June 2006). "The evolution of hyperactivity, impulsivity and cognitive diversity". J R Soc Interface. 3 (8): 399–413. doi:10.1098/rsif.2005.0102. PMC 1578754. PMID 16849269.

- ^ Glover V (April 2011). "Annual Research Review: Prenatal stress and the origins of psychopathology: an evolutionary perspective". J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 52 (4): 356–67. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02371.x. PMID 21250994.

- ^ Behavioral neuroscience of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and its treatment. New York: Springer. 13 January 2012. pp. 132–134. ISBN 978-3-642-24611-1.

- ^ Ekstein, Sivan; Glick, Benjamin; Weill, Michal; Kay, Barrie; Berger, Itai (1 October 2011). "Down Syndrome and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)". Journal of Child Neurology. 26 (10): 1290–1295. doi:10.1177/0883073811405201. ISSN 0883-0738. PMID 21628698.

- ^ Burger PH, Goecke TW, Fasching PA, Moll G, Heinrich H, Beckmann MW, Kornhuber J (September 2011). "[How does maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy affect the development of attention deficit/hyperactivity syndrome in the child]". Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr (in German). 79 (9): 500–506. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1273360. PMID 21739408.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Abbott LC, Winzer-Serhan UH (April 2012). "Smoking during pregnancy: lessons learned from epidemiological studies and experimental studies using animal models". Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 42 (4): 279–303. doi:10.3109/10408444.2012.658506. PMID 22394313.

- ^ Neuman RJ, Lobos E, Reich W, Henderson CA, Sun LW, Todd RD (15 June 2007). "Prenatal smoking exposure and dopaminergic genotypes interact to cause a severe ADHD subtype". Biol Psychiatry. 61 (12): 1320–1328. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.08.049. PMID 17157268.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Eubig PA, Aguiar A, Schantz SL (December 2010). "Lead and PCBs as risk factors for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Environ. Health Perspect. 118 (12): 1654–1667. doi:10.1289/ehp.0901852. PMC 3002184. PMID 20829149.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ de Cock M, Maas YG, van de Bor M (August 2012). "Does perinatal exposure to endocrine disruptors induce autism spectrum and attention deficit hyperactivity disorders? Review". Acta Paediatr. 101 (8): 811–818. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2012.02693.x. PMID 22458970.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Thapar, A.; Cooper, M.; Jefferies, R.; Stergiakouli, E. (March 2012). "What causes attention deficit hyperactivity disorder?". Arch Dis Child. 97 (3): 260–5. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2011-300482. PMID 21903599.

- ^ Millichap JG (February 2008). "Etiologic classification of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Pediatrics. 121 (2): e358–65. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-1332. PMID 18245408.

- ^ Eme, R (April 2012). "ADHD: an integration with pediatric traumatic brain injury". Expert Rev Neurother. 12 (4): 475–83. doi:10.1586/ern.12.15. PMID 22449218.

- ^ a b c d e f Mayes R, Bagwell C, Erkulwater JL (2009). Medicating Children: ADHD and Pediatric Mental Health (illustrated ed.). Harvard University Press. pp. 4–24. ISBN 9780674031630.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Millichap, JG; Yee, MM (February 2012). "The diet factor in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Pediatrics. 129 (2): 330–7. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2199. PMID 22232312.

- ^ Tomaska LD and Brooke-Taylor, S. Food Additives – General pp. 449–454 in Encyclopedia of Food Safety, Vol 2: Hazards and Diseases. Eds, Motarjemi Y et al. Academic Press, 2013. ISBN 9780123786135

- ^ FDA. Background Document for the Food Advisory Committee: Certified Color Additives in Food and Possible Association with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children: March 30–31, 2011

- ^ "Mental health of children and adolescents" (PDF). 15 January 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 October 2009. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ^ a b Elder TE (September 2010). "The importance of relative standards in ADHD diagnoses: evidence based on exact birth dates". J Health Econ. 29 (5): 641–656. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2010.06.003. PMC 2933294. PMID 20638739.

- ^ Parritz, R (2013). Disorders of Childhood: Development and Psychopathology. Cengage Learning. p. 151. ISBN 9781285096063.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Parens E, Johnston J (2009). "Facts, values, and Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): an update on the controversies". Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 3 (1): 1. doi:10.1186/1753-2000-3-1. PMC 2637252. PMID 19152690.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Chriss, James J. (2007). Social control: an introduction. Cambridge, UK: Polity. p. 230. ISBN 0-7456-3858-9.

- ^ Szasz, Thomas Stephen (2001). Pharmacracy: medicine and politics in America. New York: Praeger. p. 212. ISBN 0-275-97196-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapters 10 and 13". In Sydor A, Brown RY (ed.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 266, 318–323. ISBN 9780071481274.

New, palatable foods cause dopamine release from VTA neurons of the midbrain that project to the nucleus accumbens, prefrontal cortex, and other limbic structures that regulate emotion. Dopamine acts in the nucleus accumbens to attach motivational significance to stimuli associated with reward. ... It acts in the orbital prefrontal cortex to set a value on rewards ...

Therapeutic (relatively low) doses of psychostimulants, such as methylphenidate and amphetamine, improve performance on working memory tasks both in normal subjects and those with ADHD. Positron emission tomography (PET) demonstrates that methylphenidate decreases regional cerebral blood flow in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and posterior parietal cortex while improving performance of a spacial working memory task. This suggests that cortical networks that normally process spatial working memory become more efficient in response to the drug. ... [It] is now believed that dopamine and norepinephrine, but not serotonin, produce the beneficial effects of stimulants on working memory. At abused (relatively high) doses, stimulants can interfere with working memory and cognitive control ... stimulants act not only on working memory function, but also on general levels of arousal and, within the nucleus accumbens, improve the saliency of tasks. Thus, stimulants improve performance on effortful but tedious tasks ... through indirect stimulation of dopamine and norepinephrine receptors.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 6: Widely Projecting Systems: Monoamines, Acetylcholine, and Orexin". In Sydor A, Brown RY (ed.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 148, 154–157. ISBN 9780071481274.

DA has multiple actions in the prefrontal cortex. It promotes the "cognitive control" of behavior: the selection and successful monitoring of behavior to facilitate attainment of chosen goals. Aspects of cognitive control in which DA plays a role include working memory, the ability to hold information "on line" in order to guide actions, suppression of prepotent behaviors that compete with goal-directed actions, and control of attention and thus the ability to overcome distractions. Cognitive control is impaired in several disorders, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. ... Noradrenergic projections from the LC thus interact with dopaminergic projections from the VTA to regulate cognitive control. ... it has not been shown that 5HT makes a therapeutic contribution to treatment of ADHD.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Castellanos FX, Proal E (January 2012). "Large-scale brain systems in ADHD: beyond the prefrontal-striatal model". Trends Cogn. Sci. (Regul. Ed.). 16 (1): 17–26. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2011.11.007. PMC 3272832. PMID 22169776.

Recent conceptualizations of ADHD have taken seriously the distributed nature of neuronal processing [10,11,35,36]. Most of the candidate networks have focused on prefrontal-striatal-cerebellar circuits, although other posterior regions are also being proposed [10].

- ^ a b c Cortese S, Kelly C, Chabernaud C, Proal E, Di Martino A, Milham MP, Castellanos FX (October 2012). "Toward systems neuroscience of ADHD: a meta-analysis of 55 fMRI studies". Am J Psychiatry. 169 (10): 1038–1055. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11101521. PMC 3879048. PMID 22983386.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Krain AL, Castellanos FX (August 2006). "Brain development and ADHD". Clin Psychol Rev. 26 (4): 433–444. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2006.01.005. PMID 16480802.

- ^ Fusar-Poli P, Rubia K, Rossi G, Sartori G, Balottin U (March 2012). "Striatal dopamine transporter alterations in ADHD: pathophysiology or adaptation to psychostimulants? A meta-analysis". Am J Psychiatry. 169 (3): 264–72. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11060940. PMID 22294258.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Bidwell LC, McClernon FJ, Kollins SH (August 2011). "Cognitive enhancers for the treatment of ADHD". Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 99 (2): 262–274. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2011.05.002. PMC 3353150. PMID 21596055.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cortese S (September 2012). "The neurobiology and genetics of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): what every clinician should know". Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 16 (5): 422–433. doi:10.1016/j.ejpn.2012.01.009. PMID 22306277.

- ^ Gu XL (October 2010). "Deciphering the corelease of glutamate from dopaminergic terminals derived from the ventral tegmental area". J. Neurosci. 30 (41): 13549–13551. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3802-10.2010. PMC 2974325. PMID 20943895.

- ^ Lesch KP, Merker S, Reif A, Novak M (June 2013). "Dances with black widow spiders: dysregulation of glutamate signalling enters centre stage in ADHD". Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 23 (6): 479–491. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.07.013. PMID 22939004.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lambek R, Tannock R, Dalsgaard S, Trillingsgaard A, Damm D, Thomsen PH (August 2010). "Validating neuropsychological subtypes of ADHD: how do children with and without an executive function deficit differ?". J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 51 (8): 895–904. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02248.x. PMID 20406332.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nigg JT, Willcutt EG, Doyle AE, Sonuga-Barke EJ (June 2005). "Causal heterogeneity in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: do we need neuropsychologically impaired subtypes?". Biol. Psychiatry. 57 (11): 1224–1230. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.08.025. PMID 15949992.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d "Are motivation deficits underestimated in patients with ADHD? A review of the literature". Postgrad Med. 125 (4): 47–52. 2013. doi:10.3810/pgm.2013.07.2677. PMID 23933893.

Behavioral studies show altered processing of reinforcement and incentives in children with ADHD. These children respond more impulsively to rewards and choose small, immediate rewards over larger, delayed incentives. Interestingly, a high intensity of reinforcement is effective in improving task performance in children with ADHD. Pharmacotherapy may also improve task persistence in these children. ... Previous studies suggest that a clinical approach using interventions to improve motivational processes in patients with ADHD may improve outcomes as children with ADHD transition into adolescence and adulthood.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ "MerckMedicus Modules: ADHD –Pathophysiology". August 2002. Archived from the original on 1 May 2010.

- ^ Wiener JM, Dulcan MK (2004). Textbook Of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (illustrated ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing. ISBN 9781585620579. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ^ Wolraich M, Brown L, Brown RT, DuPaul G, Earls M, Feldman HM, Ganiats TG, Kaplanek B, Meyer B, Perrin J, Pierce K, Reiff M, Stein MT, Visser S (November 2011). "ADHD: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents". Pediatrics. 128 (5): 1007–1022. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2654. PMID 22003063.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sand T, Breivik N, Herigstad A (February 2013). "[Assessment of ADHD with EEG]". Tidsskr. Nor. Laegeforen. (in Norwegian). 133 (3): 312–316. doi:10.4045/tidsskr.12.0224. PMID 23381169.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Millichap JG, Millichap JJ, Stack CV (July 2011). "Utility of the electroencephalogram in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder". Clin EEG Neurosci. 42 (3): 180–184. doi:10.1177/155005941104200307. PMID 21870470.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "FDA permits marketing of first brain wave test to help assess children and teens for ADHD". United States Food and Drug Administration. 15 July 2013.

- ^ a b Steinau S (2013). "Diagnostic Criteria in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder – Changes in DSM 5". Front Psychiatry. 4: 49. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00049. PMC 3667245. PMID 23755024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Berger I (September 2011). "Diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: much ado about something" (PDF). Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 13 (9): 571–574. PMID 21991721.

- ^ Consumer Reports; Drug Effectiveness Review Project (March 2012). "Evaluating Prescription Drugs Used to Treat: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Comparing Effectiveness, Safety, and Price" (Document). Consumer Reports. p. 2.

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Owens JA (October 2008). "Sleep disorders and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Curr Psychiatry Rep. 10 (5): 439–444. doi:10.1007/s11920-008-0070-x. PMID 18803919.

- ^ Walters AS, Silvestri R, Zucconi M, Chandrashekariah R, Konofal E (December 2008). "Review of the possible relationship and hypothetical links between attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and the simple sleep related movement disorders, parasomnias, hypersomnias, and circadian rhythm disorders". J Clin Sleep Med. 4 (6): 591–600. PMC 2603539. PMID 19110891.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Lal C, Strange C, Bachman D (June 2012). "Neurocognitive impairment in obstructive sleep apnea". Chest. 141 (6): 1601–1610. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2214. PMID 22670023.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shaw M, Hodgkins P, Caci H, Young S, Kahle J, Woods AG, Arnold LE (4 September 2012). "A systematic review and analysis of long-term outcomes in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: effects of treatment and non-treatment". BMC Med. 10: 99. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-10-99. PMC 3520745. PMID 22947230.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Nigg JT, Lewis K, Edinger T, Falk M (January 2012). "Meta-analysis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms, restriction diet, and synthetic food color additives". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 51 (1): 86–97. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2011.10.015. PMID 22176942.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Sonuga-Barke EJ, Brandeis D, Cortese S, Daley D, Ferrin M, Holtmann M, Stevenson J, Danckaerts M, van der Oord S, Döpfner M, Dittmann RW, Simonoff E, Zuddas A, Banaschewski T, Buitelaar J, Coghill D, Hollis C, Konofal E, Lecendreux M, Wong IC, Sergeant J (March 2013). "Nonpharmacological interventions for ADHD: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of dietary and psychological treatments". Am J Psychiatry. 170 (3): 275–289. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12070991. PMID 23360949.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fabiano GA, Pelham WE, Coles EK, Gnagy EM, Chronis-Tuscano A, O'Connor BC (March 2009). "A meta-analysis of behavioral treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Clin Psychol Rev. 29 (2): 129–140. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2008.11.001. PMID 19131150.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kratochvil CJ, Vaughan BS, Barker A, Corr L, Wheeler A, Madaan V (March 2009). "Review of pediatric attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder for the general psychiatrist". Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 32 (1): 39–56. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2008.10.001. PMID 19248915.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Evans, SW; Owens, JS; Bunford, N (2014). "Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Journal of clinical child and adolescent psychology : the official journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53. 43 (4): 527–51. doi:10.1080/15374416.2013.850700. PMID 24245813.

- ^ Arns M, de Ridder S, Strehl U, Breteler M, Coenen A (July 2009). "Efficacy of neurofeedback treatment in ADHD: the effects on inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity: a meta-analysis". Clin EEG Neurosci. 40 (3): 180–189. doi:10.1177/155005940904000311. PMID 19715181.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hodgson, K; Hutchinson, AD; Denson, L (May 2014). "Nonpharmacological treatments for ADHD: a meta-analytic review". Journal of attention disorders. 18 (4): 275–82. doi:10.1177/1087054712444732. PMID 22647288.

- ^ Pliszka S (July 2007). "Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 46 (7): 894–921. doi:10.1097/chi.0b013e318054e724. PMID 17581453.

- ^ Antshel, KM (January 2015). "Psychosocial interventions in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: update". Child and adolescent psychiatric clinics of North America. 24 (1): 79–97. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2014.08.002. PMID 25455577.

- ^ Bjornstad G, Montgomery P (2005). Bjornstad GJ (ed.). "Family therapy for attention-deficit disorder or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD005042. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005042.pub2. PMID 15846741.

- ^ Turkington, C; Harris, J (2009). The Encyclopedia of the Brain and Brain Disorders. Infobase Publishing. p. 47. ISBN 9781438127033.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Mikami AY (June 2010). "The importance of friendship for youth with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 13 (2): 181–98. doi:10.1007/s10567-010-0067-y. PMC 2921569. PMID 20490677.

- ^ a b "Exercise reduces the symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and improves social behaviour, motor skills, strength and neuropsychological parameters". Acta Paediatr. 103 (7): 709–14. July 2014. doi:10.1111/apa.12628. PMID 24612421. Retrieved 14 March 2015.