California gold rush

| History of California |

|---|

|

| Periods |

| Topics |

| Cities |

| Regions |

| Bibliographies |

|

|

The California Gold Rush was the "first world-class gold rush."[1] The Gold Rush transformed California from a distant and quiet province to a focus of the world’s imagination. The Gold Rush laid the foundation of the “California Dream” as a place to begin again, a place where untold wealth was just waiting to be found.

The Gold Rush started in January 1848, when James W. Marshall found shiny pieces of metal in the tailrace of a sawmill he was building; tests showed the metal was gold. Word of the find spread quickly. Within a few years, hundreds of thousands of prospectors and merchants came to California from around the world, drawn by “gold fever” and the lure of easy wealth.

Gold had concentrated in the mountains of California as the result of hundreds of millions of years of geologic action. Early prospectors, called Forty-Niners, at first retrieved the gold from streams and riverbeds using simple techniques, and they later developed more sophisticated methods of gold recovery which were adopted around the world.

The Gold Rush brought wide-spread change to California. In just a few years, some 300,000 people (mostly young men) came to California from the rest of the United States and abroad. Stories of the fabulous "Golden State" and shiploads of California gold spread to every corner of the world, setting the stage for an on-going world-wide fascination with California which has lasted more than 150 years.

Discovery of gold

The Gold Rush started at Sutter's Mill near Coloma, California on January 24, 1848. James W. Marshall, a foreman working for Sacramento pioneer John Sutter, found pieces of gold in the tailrace of a lumber mill Marshall was building for Sutter along the American River.[2] Marshall quietly brought what he found to Sutter, and the two of them privately tested the findings. Dismayed that Marshall's particles passed tests for gold, Sutter wanted to keep the news quiet because he feared what would happen to his plans for an agricultural empire if there were a mass search for gold.[3] However, rumors soon started to spread and were confirmed in March 1848 by San Francisco newspaper publisher and merchant Samuel Brannan. The most famous quote of the California Gold Rush was by Brannan; after he hurriedly set up a store to sell gold prospecting supplies,[4] Brannan strode through the streets of San Francisco, holding aloft a vial of gold, shouting "Gold! Gold! Gold from the American River!"[5]

On August 19, 1848, the New York Herald was the first major newspaper in the East to report that there was a gold rush in California; on December 5, 1848, President James Polk confirmed the discovery of gold in an address to Congress.[6] Soon, waves of immigrants from around the world, later called the "Forty-Niners," invaded the Gold Country of California or “Mother Lode.” As Sutter had feared, he was ruined as his workers left in search of gold and squatters invaded his land and stole his crops and cattle.[7]

The settlement of San Francisco at first became a ghost town of abandoned ships and businesses whose owners joined the Gold Rush.[8] Then, it boomed as merchants and new people arrived. The population of San Francisco exploded from perhaps 1,000[9] in 1848 to 25,000 full-time residents by 1850.[10] Like many boom towns, the infrastructure of San Francisco and other towns near the fields were strained by the sudden influx; leftover cigar boxes and planks served as sidewalks.

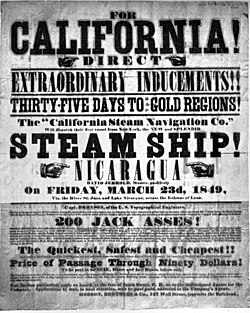

There was no easy way to get to California; Forty-Niners faced hardship and often death on the way to the gold fields. At first, most Argonauts, as they were also known, traveled by sea. From the East Coast, a sailing voyage around the tip of South America would take five to eight months,[11] and cover some 18,000 nautical miles (33,000 km). An alternative route was to sail to the Isthmus of Panama, take canoes and mules for a week through the jungle, and then on the Pacific side, wait for a ship sailing for San Francisco.[12] Eventually, most gold-seekers took the overland route across the continental United States, particularly along the California Trail.[13] Each of these routes had its own deadly hazards, from shipwreck to typhoid fever to cholera.

To meet the demands of the new arrivals, ships bearing goods from around the world—porcelain and silk from China, ale from Scotland—poured into San Francisco as well.[14] Upon reaching San Francisco, ship captains found that their crews deserted and went to the gold fields. The wharves and docks of San Francisco became a forest of masts, as hundreds of ships were abandoned. Enterprising San Franciscans then took over these abandoned ships and turned them into stores, taverns, brothels, and one into a jail.

Within a few years, there was an important but lesser-known surge of prospectors into far northern California, specifically into present-day Siskiyou County, Shasta County and Trinity County.[15] Discovery of gold nuggets at the site of present-day Yreka in 1851 brought thousands of gold-seekers up the Siskiyou Trail[16] and throughout California's northern counties.[17] Gold Rush-era settlements, such as Portuguese Flat on the Sacramento River, sprang into existence and then faded. The Gold Rush-era town of Weaverville on the Trinity River today retains the oldest continuously-used Taoist temple in California, a legacy of Chinese miners who came. While there are not many Gold Rush-era ghost towns still in existence, the well-preserved remains of the once-bustling town of Shasta, California, is a California state historic park.[18]

Gold was also discovered in Southern California but on a much smaller scale. The first discovery of gold, in the mountains north of present-day Los Angeles, had been in 1842, six years before Marshall's discovery, while California was still part of Mexico.[19] However, these first deposits—and later discoveries in Southern California mountains—attracted little notice and were of limited consequence economically.

By 1850, most of the easily accessible gold had been collected, and attention turned to the task of extracting the gold from more difficult locations. Faced with gold that was increasingly difficult to retrieve, Americans began to drive out foreigners to get at the most accessible gold that remained. The new California Legislature passed a foreign miners tax of twenty dollars per month, and American prospectors began organized attacks on foreign miners, particularly Latin Americans and Chinese.[20]

The large numbers of newcomers were driving Native Americans out of traditional hunting, fishing and food gathering areas, and conflict developed. Native Americans struck back to protect their homes and food-gathering areas. These actions provoked genocidal attacks by miners on native villages; out-gunned, the Native Americans, including women and children, were often slaughtered.[21] Those who escaped the massacres were many times unable to survive without access to their food-gathering areas, and they starved to death. Novelist and poet Joaquin Miller vividly captured one such attack in his semi-autobiographical work, Life Amongst the Modocs.

Forty-Niners

The first people to rush to the gold fields, beginning in the spring of 1848, were the residents of California themselves, primarily Americans and Europeans living in northern California, along with Native Americans and some Californios (Spanish-speaking Californians).[22]

Word of the Gold Rush spread slowly at first. The first large group of Americans to arrive were several thousand Oregonians who came down the Siskiyou Trail.[23] Next came people from Hawaii by ship and several thousand Latin Americans from Mexico, Chile[24] and Peru, both overland and by ship.[25] By the end of 1848, some 6,000 argonauts had come to California.[25] Only a small number (probably less than 500) traveled overland from the United States that year.[25]

Some of these "Forty-Eighters" (as they were sometimes called) were able to collect large amounts of easily accessible gold—in some cases, thousands of dollars worth each day.[26][27] Even ordinary prospectors averaged daily gold finds worth ten to fifteen times the daily wage of a laborer on the East Coast. A person could work for six months in the gold fields and find the equivalent of six years’ wages.[28]

By the beginning of 1849, word of the Gold Rush had spread around the world, and an overwhelming number of gold-seekers and merchants began to arrive from virtually every continent. The largest group in 1849 were Americans, arriving by the tens of thousands overland across the continent and along various ship routes.[29] Australians[30] and New Zealanders picked up the news from ships carrying Hawaiian newspapers, and thousands, infected with “gold fever,” boarded ships for California.[31] Forty-Niners came from Latin America, particularly from the mining districts of Mexico, near Sonora, Mexico.[31] Gold-seekers and merchants from Asia, primarily from China,[32] began arriving in 1849, at first in modest numbers to "Gold Mountain," the name given to California in Chinese. The first immigrants from Europe, reeling from the effects of the Revolutions of 1848 and with a longer distance to travel, began arriving in late 1849, mostly from France,[33] with some Germans, Italians, and British.[29]

It is estimated that almost 90,000 people arrived in California in 1849—about half by land and half by sea.[29] Of these, perhaps 50,000 to 60,000 were Americans, and the rest were from other countries.[29]

By 1855, some 300,000 gold-seekers, merchants, and other immigrants had arrived in California from around the world. The largest group continued to be Americans, but there were tens of thousands each of Mexicans, Chinese, French, and Latin Americans,[34] together with many smaller groups of miners, such as Filipinos and Basques.[35] A modest number of miners of African ancestry (probably less than 4,000[36]) had come from the American South, the Caribbean and Brazil.[37]

Economy

Although the conventional wisdom is that merchants made more money than miners during the Gold Rush, the reality is perhaps more complex. There were certainly merchants who profited handsomely. The wealthiest man in California during the early years of the Gold Rush was Samuel Brannan, who was a self-promoter, shopkeeper and newspaper publisher.[38] Brannan opened the first supply stores in Sacramento, Coloma, and other spots in the gold fields; just as the Gold Rush began, he purchased all the prospecting supplies available in San Francisco and re-sold them at a substantial profit.[38] Money was made by gold-seekers as well. For example, one small group of prospectors, working on the Feather River in 1848, retrieved 273 pounds (124 kg) of gold in a few months[39] (worth $2.6 million at 2006 prices).

On average, many early gold-seekers did perhaps make a modest profit, after all expenses were taken into account. Most, however, especially those arriving later, made little or wound up losing money.[38][40] Similarly, many merchants set up in settlements which did not prosper or were wiped out in one of the calamitous fires that swept the towns springing up.[41] Other businesspeople, through good fortune and hard work, reaped great rewards in shipping, entertainment, lodging, or transportation.

By 1855, the economic climate had changed dramatically. Gold could be retrieved profitably from the gold fields only by medium to large groups of workers, either in partnerships or as employees.[42] By the mid-1850s, it was the owners of the gold-mining companies who made the money. Similarly, the population of California had grown so large and so fast, and the economic base had started to diversify, that money could be made in a wide variety of conventional businesses.[43]

Path of the gold

Once the gold was recovered, there were many paths the gold itself took.

Much of the gold was used locally to purchase food, supplies and lodging for the miners. These transactions often took place using the recently recovered gold, carefully weighed out.[44] These merchants and vendors, in turn, used the gold to purchase supplies from ship captains or packers bringing goods to California.[45] The gold then left California aboard ships or mules to go to the makers of the goods from around the world.

The argonauts, having personally acquired a sufficient amount, sent the gold home or returned home, taking with them their hard-earned “diggings.” For example, one estimate is that some $80 million worth of California gold was sent to France by French prospectors and merchants.[46]

As the Gold Rush progressed, local banks and gold dealers issued “banknotes” or “drafts”—locally accepted paper currency—in exchange for gold,[47] and private mints created private gold coins.[48] With the building of the San Francisco Mint in 1854, gold bullion was turned into official United States gold coins for circulation.[49] The gold was also sent by California banks to U.S. national banks in exchange for national paper currency to be used in the booming California economy.[50]

Legal rights

When the Gold Rush began, California was virtually lawless. When gold was discovered at Sutter's Mill, California was still technically part of Mexico, under American military occupation as the result of the Mexican-American War. With the signing of the treaty ending the war on February 2, 1848, California became a part of the United States, but it was not a formal territory and was certainly not yet a state. California existed in an unusual condition of a region under military control—there was no civil legislature, executive or judicial body for the entire region.[51] Local citizens operated under a confusing and changing mixture of Mexican rules, American principles, and personal dictates.

While the treaty ending the Mexican-American War obligated the United States to honor Mexican land grants,[52] almost all of the gold fields were outside those grants. Instead, the gold fields were primarily on “public land”—land formally owned by the United States government.[53] However, there were no legal rules yet in place and no practical enforcement mechanisms.[54]

The benefit to the Forty-Niners was that the gold was “free for the taking.” In the gold fields, there was no private property, no licensing fees, and no taxes.[55] The Forty-Niners resorted to making up their own codes and setting up their own local enforcement. It was understood that a “claim” could be “staked” by a prospector, but that claim was valid only as long as it was being actively worked.[56] Disputes were sometimes handled personally and violently, and they were sometimes addressed by groups of prospectors acting as arbitrators.[53][56]

Development of gold recovery techniques

Because the gold in the California gravel beds was so richly concentrated, the early Forty-Niners simply panned for gold in California’s rivers and streams.[57] However, panning cannot be done on a large scale, and industrious miners and groups of miners graduated to "cradles," "rockers," and "long-toms" to process larger volumes of gravel.[58] At its most complex, groups of prospectors would divert the water from an entire river into a sluice, and then dig for gold in the exposed river bottom.[59] Modern estimates by the U.S. Geological Survey are that some 12 million ounces (373 t) of gold were removed in the first five years of the Gold Rush (worth approximately US$7.2 billion at November 2006 prices).[60]

In the next stage, by 1853, the first hydraulic mining was used on ancient gold-bearing gravel beds which were on hillsides and bluffs in the gold fields.[61] In hydraulic mining (which was invented in California at this time), a high pressure hose directs a powerful stream of water at gold-bearing gravel beds. The loosened gravel and gold then pass over sluices, with the gold settling to the bottom where it is collected. By the mid-1880s, it is estimated that 11 million ounces (342 t) of gold (worth approximately US$6.6 billion at November 2006 prices) had been recovered via "hydraulicking."[60]

A byproduct of this method of extraction was that large amounts of gravel and silt, in addition to heavy metals and other pollutants, went into streams and rivers.[62] Many areas still bear the scars of hydraulic mining since the resulting exposed earth and downstream gravel deposits are unable to support plant life.[63]

The final stage to recover loose gold was to prospect for gold which had washed down over millions of years into the flat river bottoms and sandbars of California’s Central Valley and other gold-bearing areas of California (such as Scott Valley in Siskiyou County). By the late 1890s, dredging technology (which was also invented in California) had become economical,[64] and it is estimated that more than 20 million ounces (622 t) were recovered by dredging (worth approximately US$12 billion at November 2006 prices).[60]

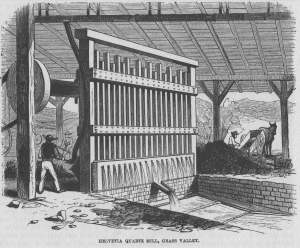

The Forty-Niners also engaged in "hard-rock" mining, that is, extracting the gold directly from the rock which contained it (typically quartz), usually by digging and blasting to follow and remove veins of the gold-bearing quartz.[65] Once the gold-bearing rocks were brought to the surface, the rocks were crushed, and the gold was leached out, typically by using arsenic or mercury (another source of environmental contamination).[66] Eventually, hard-rock mining wound up being the single largest source of gold produced in the Gold Country.[60]

Effects on California and elsewhere

Historians have reflected on the Gold Rush and its effect on California. Historian Hubert Howe Bancroft used the phrase that the Gold Rush advanced California into a "rapid, monstrous maturity."[67] Historian Kevin Starr stated, for all its problems and benefits, the Gold Rush established the "founding patterns, the DNA code, of American California."[67]

The Gold Rush laid the foundation of the “California Dream”—California as a place to begin again, where fabulous riches rewarded hard work and good luck. This gold rush mentality continued in the agricultural expansion of California of the 19th century and early 20th century, in the oil boom of the early 1900s, in the entertainment industry growth of the 1920s and 1930s, and in the post-war population and industrial spurt of the late 1940s and early 1950s. The most recent "gold rush," centered on California’s Silicon Valley, is only the latest in a long series of such events in California.

Immediate effects

The arrival of hundreds of thousands of new people within a few years, compared to a population of some 15,000 Europeans and Californios previously,[68] had many dramatic effects.

The human and environmental costs of the Gold Rush were substantial. Native Americans became the victims of disease, starvation and genocidal attacks;[69] the Native American population, estimated at 150,000 in 1845, was less than 30,000 by 1870.[70] Explicitly racist attacks and laws sought to drive out Chinese and Latin American immigrants.[71] The toll on the American immigrants could be severe as well: one in twelve Forty-Niners lost his or her life, as the death and crime rates during the Gold Rush were extraordinarily high, and the resulting vigilantism took its toll.[72] In addition, the environment suffered as gravel, silt and toxic chemicals from prospecting operations killed fish and destroyed habitats.

The Gold Rush propelled California from a little-known frontier to a center of the global imagination and the destination of hundreds of thousands of people. The new immigrants often showed remarkable inventiveness and civic-mindedness. For example, in the midst of the Gold Rush, towns and cities were chartered, a state constitutional convention was convened, a state constitution written, elections held, and representatives sent to Washington, D.C. to negotiate the admission of California as a state.[73] Large-scale agriculture (California's second "Gold Rush"[74]) began during this time.[75] Roads, schools, churches,[76] and civic organizations quickly came into existence.[73]

The vast majority of the immigrants were Americans. Pressure grew for better communications and political connections to the rest of the United States, leading to statehood for California on September 9, 1850, in the Compromise of 1850 as the 31st state of the United States.

The Gold Rush wealth and population increase led to significantly improved transportation between California and the East Coast. The Panama Railway, spanning the Isthmus of Panama, was finished in 1855.[77] Steamships began regular service from San Francisco to Panama, where passengers, goods and mail would take the train across the Isthmus and board steamships headed to the East Coast. One ill-fated journey, that of the S.S. Central America, ended in disaster as the ship sank in a hurricane off the coast of the Carolinas in 1857, with an estimated three tons of California gold aboard.[78][79]

Within a few years thereafter, in 1863, the groundbreaking ceremony for the western leg of the First Transcontinental Railroad was held in Sacramento. The line's completion some six years later, financed in part with Gold Rush money,[80] united California with the central and eastern United States; travel that had taken weeks or even months could be accomplished in days.

The Gold Rush stimulated economies around the world as well. Farmers in Chile, Australia, and Hawaii, found a huge new market for their food; British manufactured goods were in high demand; clothing and even pre-fabricated houses arrived from China.[81] The return of large amounts of California gold to pay for these goods raised prices and stimulated investment and the creation of jobs around the world.[82]

Longer-term effects

California’s name became indelibly connected with the Gold Rush, and with the “California Dream”. Historian H.W. Brands noted that in the years after the Gold Rush, the California Dream spread to the rest of the United States and became part of the new “American Dream.”

”The old American Dream . . . was the dream of the Puritans, of Benjamin Franklin’s Poor Richard . . . of men and women content to accumulate their modest fortunes a little at a time, year by year by year. The new dream was the dream of instant wealth, won in a twinkling by audacity and good luck. [This] golden dream . . . became a prominent part of the American psyche only after Coloma.”[83]

The Gold Rush’s California Dream has shone brightly for over 150 years, as generations of immigrants have flocked to California from around the globe, and California farmers, oil drillers,[84] movie makers,[85] airplane builders,[86] and “dot-com” entrepreneurs have exported their products to the world and have become wealthy doing so.[87]

Included among the modern legacies of the California Gold Rush are the California state motto, "Eureka" ("I have found it"), and the state nickname, "The Golden State," as well as place names such as Rough and Ready, Placerville, Whiskeytown, Drytown, Angels Camp, Happy Camp, and Sawyer's Bar. The San Francisco 49ers NFL football team, and the athletic teams of California State University, Long Beach, are named for the prospectors of the California Gold Rush. The literary history of the Gold Rush is reflected in the works of Mark Twain (The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County), Bret Harte (A Millionaire of Rough-and-Ready), Joaquin Miller (Life Amongst the Modocs), and many others.

Today, a state highway travels through the Sierra Nevada foothills, connecting many Gold Rush-era towns such as Placerville, Auburn, Grass Valley, Coloma, Jackson, and Sonora. This road is designated as California State Route 49. Route 49 also passes very near Columbia State Historic Park, a protected area encompassing the historic business district of the town of Columbia; the park has preserved many Gold Rush-era buildings, which are presently occupied by tourist-oriented businesses.

Geology

How the gold came to be uniquely in California, and not elsewhere, so that the "first world-class gold rush"[88] could take place there, is a story involving global forces.

Scientists believe that over a span of at least 400 million years, gold which had been widely dispersed in the Earth’s crust became more concentrated by geologic actions into the gold-bearing regions of California. Only gold which is concentrated can be economically recovered. Some 400 million years ago, California lay at the bottom of a large sea; underwater volcanoes deposited lava and minerals (including gold) onto the sea floor; sometimes enough that islands were created.[89] Between 400 million and 200 million years ago, geologic movement forced the sea floor and these volcanic islands and deposits eastwards, colliding with the North American continent, which was moving westwards.[90]

Beginning about 200 million years ago, tectonic pressure forced the sea floor beneath the American continental mass.[91] As it sank, or subducted, the sea floor heated and melted into very large molten masses (magma). Being lighter and hotter than the ancient continental crust above it, this magma forced its way upward, cooling as it rose[92] to become the granite rock found throughout the Sierra Nevada and other mountains in California today — such as the sheer rock walls and domes of Yosemite Valley.[93] As the hot magma cooled, solidified, and came in contact with water, minerals with similar melting temperatures tended to concentrate themselves together.[93] As it solidified, gold became concentrated within the magma, and during this cooling process, veins of gold formed within fields of quartz[92] because of the similar melting temperatures of both.[94]

As the Sierra Nevada and other mountains in California were forced upwards by the actions of tectonic plates, the solidified minerals and rocks were raised to the surface and exposed to rain, ice and snow.[95] The surrounding rock then eroded and crumbled, and the exposed gold and other materials were carried downstream by water. Because gold is more dense than almost all other minerals, this process further concentrated the gold as it sank, and pockets of gold gathered in quiet gravel beds along the sides of old rivers and streams.[96]

The California mountains rose and shifted several times within the last fifty million years, and each time, old streambeds moved and were dried out, leaving the deposits of gold resting within the ancient gravel beds where the gold had been collecting.[97] Newer rivers and streams then developed, and some of these cut through the old channels, exposing the gold.[97] The Forty-Niners first focused their efforts on these deposits of gold, which had been concentrated in the old gravel beds by hundreds of millions of years of geologic action.

See also

- List of people associated with the California Gold Rush

- Virginia gold mining (beginning 1804)

- Georgia Gold Rush (1840s)

- Australian gold rush (1850s)

- Fraser Canyon Gold Rush (late 1850s)

- Colorado Gold Rush (early 1860s)

- Central Otago Gold Rush (1860s)

- Witwatersrand Gold Rush (1880s)

- Klondike Gold Rush (1890s)

Notes

- ^ Hill, Mary (1999). Gold: the California story. Berkeley and Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press. pp. p. 1.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888). History of California, Volume 23: 1848 - 1859. San Francisco: The History Company. pp. pp. 32-34.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888), pp. 39-41.

- ^ Holliday, J. S. (1999). Rush for riches; gold fever and the making of California. Oakland, California, Berkeley and Los Angeles: Oakland Museum of California and University of California Press. pp. p. 60.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888), pp. 55-56.

- ^ Starr, Kevin (2005). California: a history. New York: The Modern Library. pp. p. 80.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888), pp. 103-105.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888), pp. 59-60.

- ^ Holliday, J. S. (1999), p. 51 (“800 residents”).

- ^ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (1999). A golden state: mining and economic development in Gold Rush California (California History Sesquicentennial Series, 2). Berkeley and Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) p. 187 - ^ Brands, H.W. (2003). The age of gold: the California Gold Rush and the new American dream. New York: Doubleday. pp. pp. 103-121.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Brands, H.W. (2002), pp. 75-85. Another route across Nicaragua was developed in 1851; it was not as popular as the Panama option. Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 252-253.

- ^ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), p. 5

- ^ U.S. National Park Service, Found! The Wreck of the Frolic (accessed Oct. 16, 2006).

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888), pp. 363-366.

- ^ Dillon, Richard (1975). Siskiyou Trail. New York: McGraw Hill.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help)pp. 361-362 - ^ Wells, Harry L. (1881). History of Siskiyou County, California. Oakland, California: D.J. Stewart & Co. pp. pp. 60-64.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ The buildings of Bodie, the best-known ghost town in California, date from the 1870s and later, well after the end of the Gold Rush.

- ^ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (1999), p. 3.

- ^ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), p. 9

- ^ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), p. 8

- ^ Brands, H.W. (2002), pp. 43-46.

- ^ Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000). Rooted in barbarous soil: people, culture, and community in Gold Rush California. Berkeley and Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press. pp. pp. 50-54.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help);|pages=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brands, H.W. (2002), pp. 48-53.

- ^ a b c Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000), pp. 50-54. Cite error: The named reference "Starr48" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Brands, H.W. (2002), pp. 197-202

- ^ Holliday, J. S. (1999) p. 63. Holliday notes these luckiest prospectors were recovering gold, valued in modern-day dollars, worth in excess of $1 million, in short amounts of time.

- ^ Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000), p. 28.

- ^ a b c d Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000), pp. 57-61. Cite error: The named reference "Starr49" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Brands, H.W. (2002), pp. 53-61.

- ^ a b Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000), pp. 53-56.

- ^ Brands, H.W. (2002), pp. 61-64.

- ^ Brands, H.W. (2002), pp. 93-103.

- ^ Brands, H.W. (2002), pp. 193-194.

- ^ Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000), p. 62.

- ^ Another estimate is 2,500 Forty-Niners of African ancestry. Rawls, James, J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), p. 5

- ^ Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000), pp. 67-69.

- ^ a b c Holliday, J. S. (1999) pp. 69 – 70. Cite error: The named reference "HollProf" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Holliday, J. S. (1999), p. 63

- ^ One estimate is that fewer than one in twenty prospectors profited financially from their California gold-seeking. Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), p. 7.

- ^ For example, Joshua A. Norton at first acquired a fortune but was forced to declare bankruptcy in 1858, and he wandered the streets of San Francisco, styling himself "Emperor Norton I." By contrast, a businessman who went on to great success was Levi Strauss, who first began selling denim over-alls in San Francisco in 1853 (the famous Levi jeans were not invented until the 1870s).

- ^ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 52-68

- ^ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 193-197.

- ^ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 212-214.

- ^ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 256-259.

- ^ Holliday, J. S. (1999) p. 90

- ^ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 193-197; 214-215.

- ^ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), p. 214.

- ^ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), p. 212.

- ^ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 226-227.

- ^ Holliday, J. S. (1999), pp. 115 - 123

- ^ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), p. 235

- ^ a b Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), p. 123-125 Cite error: The named reference "RawlsPublic" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), p.127. There were fewer than 1,000 U.S. soldiers in California at the beginning of the Gold Rush.

- ^ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), p. 27

- ^ a b Clay, Karen and Wright, Gavin. (2005), pp. 155-183. Cite error: The named reference "ClayRights" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Brands, H.W. (2002), pp. 198-200.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888), pp. 87-88.

- ^ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), p. 90

- ^ a b c d Mining History and Geology of the Mother Lode (accessed Oct. 16, 2006)

- ^ Starr, Kevin (2005), p. 89.

- ^ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 32-36

- ^ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 116-121

- ^ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 1991

- ^ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 36-39

- ^ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 39-43

- ^ a b Starr, Kevin (2005), p. 80.

- ^ Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000), p. 50. Other estimates are that there were 7,000 - 13,000 non-Native Americans in California before January 1848. See Holliday, J. S. (1999), pp. 26, 51.

- ^ Heizer, Robert F. (1974). The destruction of California Indians. Lincoln and London: Univ. of Nebraska Press. pp. pp. 243.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Starr, Kevin (2005), p. 99.

- ^ Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000), pp. 56-79.

- ^ Starr, Kevin (2005), pp. 84-87.

- ^ a b Starr, Kevin (2005), pp. 91-93.

- ^ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 243-248. By 1860, California had over 200 flour mills, and was exporting wheat and flour around the world. Ibid. at 278-280.

- ^ Starr, Kevin (2005), pp. 110-111.

- ^ Starr, Kevin (1973). Americans and the California dream: 1850-1915. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. pp. 69-75.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Harper's New Monthly Magazine March 1855, Volume 10, Issue 58, p.543.

- ^ Hill, Mary (1999), pp. 192-196.

- ^ Another notable ship wreck was the steamship Winfield Scott, bound to Panama from San Francisco, which crashed into Anacapa Island off the Southern California coast in December 1853. All hands and passengers were saved, along with the cargo of gold, but the ship was a total loss.

- ^ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 278-279

- ^ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 285-286

- ^ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 287-289

- ^ Brands, H.W. (2002), p. 442.

- ^ See, e.g., Signal Hill, California, Bakersfield, California

- ^ 20th Century-Fox, MGM, Paramount, RKO, Warner Bros., Universal Pictures, Columbia Pictures, and United Artists are among the most recognized entertainment industry names centered in California; see also Film studio

- ^ Hughes Aircraft, Douglas Aircraft, North American Aviation, Northrop, Lockheed Aircraft were among the complex of companies in the aerospace industry which flourished in California during and after World War II

- ^ Google buys YouTube for $1.65 Billion "Google Bets Big on Videos" By Chris Gaither and Dawn C. Chmielewski, Los Angeles Times October 10, 2006, retrieved October 10, 2006.

- ^ Hill, Mary (1999), p. 1.

- ^ Hill, Mary (1999), p. 167.

- ^ Hill, Mary (1999), p. 168.

- ^ Hill, Mary (1999), pp. 168-69.

- ^ a b Brands, H.W. (2002), pp. 195-196.

- ^ a b Hill, Mary (1999), pp. 149-58.

- ^ Hill, Mary (1999), pp. 174-78.

- ^ Hill, Mary (1999), pp. 169-173.

- ^ Hill, Mary (1999), pp. 94-100.

- ^ a b Hill, Mary (1999), pp. 105-110.

References

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1884-1890) History of California, vols. 18-24, The works of Hubert Howe Bancroft, complete text online

- Brands, H.W. (2003). The age of gold: the California Gold Rush and the new American dream. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0385720882.

- Clay, Karen (2005). "Order Without Law? Property Rights During the California Gold Rush". Explorations in Economic History. 42 (2): 155–183. ISSN: 0014-4983.

{{cite journal}}: Text "Wright, Gavin" ignored (help) Abstract: The system of mining claims created during the 19th century California gold rush was not the precursor of modern secure property rights. When the gold rush began in 1848 there were no federal regulations governing mining rights, and disputes about claim jumping were frequent and sometimes violent. In order to minimize violence and maximize the discovery of gold, regulations were created at the local level to clarify when a mining site could be considered abandoned and available for a new claim. Despite the presence of third-party enforcement of the regulations, however, miners had to be constantly vigilant to protect their claims, as they had not established a permanent property right.

- Dillon, Richard (1975). Siskiyou Trail. New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 0070169802.

- "Google Bets Big on Videos" By Chris Gaither and Dawn C. Chmielewski, Los Angeles Times October 10, 2006, retrieved October 10, 2006.

- Harper's New Monthly Magazine March 1855, Volume 10, Issue 58 complete text online

- Heizer, Robert F. (1974). The destruction of California Indians. Lincoln and London: Univ. of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803272626.

- Hill, Mary (1999). Gold: the California story. Berkeley and Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press. ISBN 0520215478.

- Holliday, J. S. (1999). Rush for riches; gold fever and the making of California. Oakland, California, Berkeley and Los Angeles: Oakland Museum of California and University of California Press. ISBN 0520214013.

- Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (1999). A golden state: mining and economic development in Gold Rush California (California History Sesquicentennial Series, 2). Berkeley and Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press. ISBN 0520217713.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Starr, Kevin (1973). Americans and the California dream: 1850-1915. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195042336.

- Starr, Kevin (2005). California: a history. New York: The Modern Library. ISBN 0679642404.

- Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000). Rooted in barbarous soil: people, culture, and community in Gold Rush California. Berkeley and Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press. ISBN 0520224965.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Wells, Harry L. (1881). History of Siskiyou County, California. Oakland, California: D.J. Stewart & Co. ASIN B0006YP8IE. (reprinted 1971 Siskiyou County Historical Society)

Further reading

- Burchell, Robert A. "The Loss of a Reputation; or, The Image of California in Britain before 1875," California Historical Quarterly 53 (Summer I974): 115-30, stories about Gold Rush lawlessness slowed immigration for two decades

- Burns, John F. and Orsi, Richard J., eds. (2003). Taming the elephant: politics, government, and law in pioneer California. Berkeley and Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press. ISBN 0520234138.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) complete text online

- Drager, K., and Fracchia, C. (1997). The golden dream: California from Gold Rush to statehood. Portland, OR: Graphic Arts Center Publishing Company. ISBN 1558683127.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Eifler, Mark A. (2002). Gold Rush capitalists: greed and growth in Sacramento. Univ. of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0826328229.

- Holliday , J. S. and Swain, William (1981). The world rushed in: the California Gold Rush experience. Norman: Univ. of Oklahoma Press (reprint ed. 2002). ISBN 080613464X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Hurtado, Albert L. (2006). John Sutter: a life on the North American frontier. Norman: Univ. of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 080613772X.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help)

- Johnson, Susan Lee (2001). Roaring Camp: the social world of the California Gold Rush. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0393320995.

- Levy, JoAnn (1990). They saw the elephant: women in the California Gold Rush. Norman: Univ. of Oklahoma Press (reprint ed. 1992). ISBN 0806124733.

- Miller, Joaquin (1873). Life amongst the Modocs:unwritten history. Berkeley: Heyday Books; Reprint edition (January 1996). ISBN 0930588797.

- Owens, Kenneth N., ed. (2002). Riches for all: the California Gold Rush and the world. Univ. of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803286171.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Roberts, Brian (2000). American alchemy: the California Gold Rush and middle-class culture. Univ. of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0807848565.

- Rohrbough, Malcolm J. (1998). Days of gold: the California Gold Rush and American nation. Berkeley and Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press. ISBN 0520216598.

- Watson, Matthew A. "The Argonauts of '49: Class, Gender, and Partnership in Bret Harte's West." Western American Literature 2005 40(1): 33-53. Issn: 0043-3462 Abstract: Discusses Bret Harte's notion of Western partnership in such California gold rush stories as "The Luck of Roaring Camp` (1868), "Tennessee's Partner" (1869), and "Miggles" (1869). While critics have long recognized Harte's interest in gender constructs, Harte's depictions of Western partnerships also explore "changing dynamics of economic relationships and gendered relationships through terms of contract, mutual support, and the bonds of labor."

External links

- California Gold Rush chronology

- Museum of the Siskiyou Trail

- Description by John Sutter of the Discovery of Gold

- Marshall Gold Discovery State Historic Park

- Columbia State Historic Park

- Impact of Gold Rush on California

- California Gold Rush timeline

- The Gold Rush: fun facts

- Gold Rush geology

- USGS circular on the geology of gold

- Weaverville State Historic Park

- Shasta State Historic Park

- Chinese name for California and Chinese miners in California

- San Francisco harbor Gold Rush archeology

- Gold Rush era ship wreck

- S.S. Central America information