Revolver (Beatles album)

| Untitled | |

|---|---|

Revolver is the seventh studio album by the English rock band the Beatles. It was released on 5 August 1966 in the United Kingdom and on 8 August 1966 in the United States. The album was produced by George Martin and features many tracks with an electric guitar-rock sound that contrasts with their previous LP, the folk rock-inspired Rubber Soul (1965).

In the UK, Revolver's 14 tracks were released to radio stations throughout July 1966, "building anticipation for what would clearly be a radical new phase in the group's recording career".[2] The album spent 34 weeks on the UK Albums Chart, earning the number one spot on 13 August 1966.[3] It also reached number one on the Billboard Top LPs, where it stayed for six weeks.

Revolver was ranked number 1 in the All-Time Top 1000 Albums and number 3 in Rolling Stone magazine's list of the 500 greatest albums of all time.[4] A remastered CD of the album was released on 9 September 2009. This was Revolver's first remastering since its 1987 digital compact disc release. In 2013, after the British Phonographic Industry changed their sales award rules, the album was declared as having gone platinum.[5]

Background

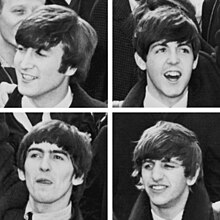

Top: Lennon, McCartney

Bottom: Harrison, Starr

In December 1965 the Beatles' album Rubber Soul was released to wide critical acclaim.[6] According to the author Robert Rodriguez, it was seen as a "major breakthrough beyond the Merseybeat sound of their previous five LPs".[6] In his view, the album "emerged as a triumph that hinted at grander ambitions", challenging the "existing rock paradigm".[7]

The manager Brian Epstein had planned for the Beatles to begin work in April 1966 on what would be their third film soundtrack, but when the band members failed to agree on a suitable script, the plans were scrapped in favour of recording a new LP.[8] Epstein had cleared three months of the Beatles' schedule to accommodate the planned film, and he rushed to book touring dates after the production was abandoned. This afforded the group more free time then they had enjoyed since signing with Epstein several years earlier, which sparked their creativity.[9] On 1 May they performed for a crowd of 10,000 people during NME's annual Poll-Winners All-Star Concert at Empire Pool, in Wembley. The concert was their last before a paying audience in the United Kingdom.[10] Already one month into recording sessions for Revolver, the Beatles played a lackluster set that conveyed their growing disinterest in live performance.[6] According to Rodriguez, there was an almost continuous series of rumours circulating in 1966 that they had decided to break up.[11]

John Lennon had been the Beatles' dominant creative force through 1965, when Paul McCartney began to exert his influence in the group beyond sharing the songwriting, musical accompaniment and assisting with arrangement.[12] By 1966 he had attained an approximately equal position with Lennon, who had to that point contributed the lead vocal for the majority of their singles, album openers and closers.[13] The recording of Revolver marks the midpoint between the period of the Beatles' career that was dominated by Lennon – who was by this time growing increasingly disinterested in his life as a Beatle – and the period dominated by McCartney, who would provide the group's artistic direction for every post-Revolver project.[14]

Recording and production

According to Rodriguez, Revolver marks the first time that the Beatles "deliberately incorporated" the studio into the "conception of the recordings they made", versus using it "merely as a tool to capture performances".[15]

A key production technique that the Beatles used for the first time on Revolver was automatic double tracking (ADT), invented by EMI engineer Ken Townsend on 6 April 1966. This technique used two linked tape recorders to automatically create a doubled vocal track. The standard method was to double the vocal by singing the same piece twice onto a multitrack tape, a task Lennon particularly disliked. The Beatles were reportedly delighted with the invention, and used it extensively on Revolver. ADT quickly became a standard pop production technique, and led to related developments, including the artificial chorus effect.

Music and lyrics

In Rodriguez's view, whereas Sgt. Pepper is a "period piece" that is "inextricably tied to its time", Revolver is "crackling with potent immediacy".[16] He credits the album with influencing the development of a diversity of music genres, including electronica, punk rock and world music. In his opinion the album's "eclecticism ... is seen by many as its most appealing quality".[16] Womack identifies "I'm Only Sleeping"'s preoccupation with dreams, and the references to death found in the lyric to "Tomorrow Never Knows" as examples of the Beatles' exploration of "phenomenologies of consciousness" on Revolver.[17] The songs represent two important elements of the human life cycle that are "philosophical opposites".[17]

Side one

In Womack's opinion, Harrison's overdubbed opening count-in of "Taxman" is deliberately off rhythm and out of tempo.[19] Riley credits the contrived atmosphere with establishing the "new studio aesthetic of Revolver".[20] He describes Harrison's vocals, which were treated with heavy compression and ADT, as "angry" and "poisoned with acridity".[21] McCartney's active bassline features glissandi that are reminiscent of Motown's James Jamerson. He also performed the song's Indian-styled lead guitar solo, which spans two octaves and utilises the Dorian mode.[22] The track was intended as a protest against the high marginal tax rates paid by top earners like the Beatles, which were sometimes as much as 95 percent of their income; hence: "Should five percent appear too small, be thankful I don't take it all."[23] Lennon assisted Harrison with the song's writing, contributing the line: "My advice for those who die: declare the pennies on your eyes."[23] The lyric mentions "Mr Wilson" and "Mr Heath", referring to Harold Wilson and Edward Heath, who were, respectively, the British Labour Prime Minister and Conservative Leader of the Opposition at the time.[24] Rodriguez credits "Taxman" as the first Beatles song written about "topical concerns".[25] The author Shaugn O'Donnell describes it as a "frame or doorway, a boundary between reality and the mystical world" of the album.[19]

Womack describes "Eleanor Rigby" as a "narrative about the perils of loneliness", including the track among the Beatles' "most fully realized songs".[26] The story involves the title character, who is an aging spinster, and a lonely priest named Father McKenzie who writes "sermons that no one will hear".[27] He presides over Rigby's funeral and acknowledges that despite his efforts, "no one was saved".[28] The lyric was the product of a group effort, with Harrison, Starr and Lennon contributing to McCartney's song.[29][nb 1] Martin arranged the track's string octet, drawing inspiration from Bernard Herrmann's 1960 film score for Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho.[31] Everett describes the recording's timbre as "dry" and "gritty", which he finds "particularly effective when the cellos double the melody as the priest wipes dirt from his hands".[32] McCartney added a vocal countermelody to the song's last refrain that was treated with ADT and channeled through a Leslie speaker.[33] The musicologist Ian MacDonald notes that, because most pop songs avoid the topic of death, "Eleanor Rigby"'s embrace of the taboo subject "came as quite a shock" to listeners in 1966.[34] In Riley's opinion, "the corruption of "Taxman" and the utter finality of Eleanor's fate makes the world of Revolver more ominous than any other pair of opening songs could."[35][nb 2]

In the opinion of the Beatles biographer Jonathan Gould, the backwards guitar solo on "I'm Only Sleeping" seems to "suspend the laws of time and motion to simulate the half-coherence of the state between wakefulness and sleep".[38] According to MacDonald, Lennon wanted his vocal to sound like a "papery old man's voice", so it was treated with ADT and subjected to varispeeding until a desirable sound was achieved, leaving the vocal at E minor, one semitone lower than the original.[37] Everett notes that the song's unstructured melody never commits to the tonic, instead favouring the dominant.[39] He praises the recordings "unusual timbres", describing the song as a "particularly expressive text painting".[39] Womack credits the combination of Lennon's airy vocals, McCartney's "pensive bassline" and Harrison's "otherworldly backward guitar solo" with "establish[ing] an appropriately ethereal mood" that urges the listener to embrace the "dreamworld of sleep".[17] Riley identifies the song as Revolver's first allusion to escapism.[35]

"Love You To" marks Harrison's first foray into Hindustani classical music. The song's melody, which MacDonald describes as "sourly repetitious in its author's usual saturnine vein", is based on the five highest notes of C minor in Dorian mode.[40] Musicians from the North London Asian Music Circle performed the instrumentation, including a sitar part that had been wrongly attributed to Harrison.[40] The recording also includes swarmandal, tabla and tambura.[41] Everett identifies the track's change of metre as its most salient feature, a characteristic that was without precedent in the Beatles' catalogue prior to the song, but that would influence Lennon and feature prominently on their following album, Sgt. Pepper, which contains five songs with changing metres.[42] Everett compares the "bitterness" of the lyric with Harrison's previous songs, "Don't Bother Me" and "Think for Yourself".[41] In Womack's opinion, the lyrics address the speaker's desire for "immediate sexual gratification", serving as a "rallying call to accept our inner hedonism and release our worldly inhibitions".[43] The track is the first by the Beatles to eschew the use of Western instruments, a shift that Riley characterises as Harrison "trading in the religion of Chuck Berry's guitar for Ravi Shankar's meditative sitar".[44]

"Here, There and Everywhere" was inspired by the Beach Boys' song "God Only Knows".[43][nb 3] McCartney's double-tracked vocal was treated with varispeeding, resulting in a higher pitch at playback than the original.[46] Womack notes the introductory vocals, which shift from 9/8 to 7/8 to 4/4 within the span of twelve words.[43] According to Everett, "nowhere else does a Beatles introduction so well prepare a listener for the most striking and expressive tonal events that lie ahead."[47] Womack characterises the song as a romantic ballad "about living in the here and now" and "fully experiencing the conscious moment".[43] He notes that, with the preceding track, "Love You To", the album expresses "corresponding examinations of the human experience of physical and romantic love".[43] Riley describes "Here, There and Everywhere" as "the most perfect song" that McCartney has ever written.[48] In his opinion, the track "domesticates" the "eroticisms" of "Love You To", drawing comparison with the concise writing of Rodgers and Hart.[44] McCartney wrote the song in early June 1966, towards the end of the Revolver sessions, and as the Beatles were under pressure to complete the album before their scheduled flight to Germany on 23 June for a European tour.[49][nb 4]

Womack describes "Yellow Submarine" as "a simple tune about the joys of carefree living".[51] McCartney wrote the song, which he characterises as a "kid's story", as a vehicle for Starr's limited vocal range.[51] With the help of Martin and Emerick, as well as the Rolling Stones' Brian Jones and Mick Jagger and the roadies Neil Aspinall and Mal Evans, the Beatles attempted to create a nautical atmosphere by mixing the sounds of various instruments, including gongs, whistles and bells with an assortment of Studio Two's sound effect units.[51] Lennon recorded the track's superimposed voices in Abbey Road's echo chamber, recalling what Womack describes as "a forgotten vestige of a Liverpudlian, seafaring past".[52] In Riley's opinion, the juxtaposition of McCartney's graceful tenor vocals in "Here, There and Everywhere" with Starr's "throaty" baritone croon in "Yellow Submarine" provides an element of comic relief that only the Beatles could successfully achieve.[53] He describes the song as "exactly suited" to Starr's "humble charm", noting the track's clever mix of comedy in the style of The Goon Show with satire inspired by Spike Jones.[54] According to Riley, "'Yellow Submarine' doesn't subvert Revolver's darker moods; it provides joyous distraction from them."[54][nb 5]

The light atmosphere of "Yellow Submarine" is broken by what Riley describes as "the outwardly harnessed, but inwardly raging guitar" that introduces "She Said She Said".[54] He praises the song's expression of the "primal urge" for innocence, which imbues the lyric with "complexity", as the speaker suffers through feelings of "inadequacy", "helplessness" and "profound fear".[54] In his opinion, the track's "intensity is palpable" and "the music is a direct connection to [Lennon's] psyche".[54][nb 6] "She Said She Said" marks the second time that a Beatles arrangement utilised a shifting metre, as the foundation of 4/4 briefly switches to 3/4 with the lyrics: "when I was a boy, everything was right", before settling back into 4/4.[57] The song was recorded during a single nine-hour session on 21 June, one day before the album's completion deadline.[58] MacDonald characterises the track as "the antithesis of McCartney's impeccable neatness" and "one of the most irregular things that Lennon ever wrote".[59] Owing to an argument in the studio, McCartney did not contribute to the recording, leaving Harrison to perform the bassline in addition to the lead guitar and harmony vocals.[60] The lyric was inspired in part by a conversation that Lennon had with the actor Peter Fonda in August 1965. The two men were under the influence of LSD at a rented house in Benedict Canyon, and during a conversation Fonda commented: "I know what it's like to be dead", because as a child he had technically died during an operation.[50] Lennon, fearing that the somber tone of the story might lead to a bad trip, asked Fonda to leave the party.[59] Riley notes that by ending the first side of Revolver with "She Said She Said", the Beatles return to the ominous mood established by the album's first two songs.[61]

Side two

"For No One" is a melancholy song featuring McCartney playing clavichord and a horn solo played by Alan Civil. He also played lead guitar on two tracks, one being a guitar solo on "Taxman" and the other being a dual guitar part with George Harrison on "And Your Bird Can Sing".[62] The song "And Your Bird Can Sing" is primarily by John Lennon, with Paul McCartney claiming to have helped on the lyric, estimating the song as "80–20" to Lennon. [63]

Harrison also wrote "I Want to Tell You", about his difficulty expressing himself in words. "Love You To" marked a significant expansion of his burgeoning interest in Indian music and the sitar,[64] which started with "Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)" on Rubber Soul. It was the intro to "Love You To" that was playing in the background when Harrison's character first appears in Yellow Submarine, the animated Beatles film released in 1968.

McCartney's "Got to Get You into My Life" was influenced by the Motown Sound[65] and used brass instrumentation extensively. Although cast in the form of a love song, McCartney described the song as an "ode to pot".[66] It was released as a single in the US in 1976, ten years after Revolver, to promote the compilation album Rock 'n' Roll Music on which it appeared. (The vocal in the fade out at the end of the song is different on the mono version than on the stereo version. The last text line "What are you doing to my life?" can only be heard on the mono version).[citation needed]

Rodriguez describes "Tomorrow Never Knows" as "the greatest leap into the future" that the Beatles "had yet taken".[8] The group's innovation in the recording studio reached its apex with the Lennon's composition, which was an early example in the emerging counterculture genre of psychedelic music,[67] and included such groundbreaking techniques as reverse guitar, processed vocals and looped tape effects. Musically, it is drone-like, with a strongly syncopated, repetitive drum-beat played over a single chord. The lyrics were inspired by Timothy Leary's book, The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on The Tibetan Book of the Dead. The title was inspired by a Ringo Starr malapropism.[68] The song's harmonic structure is derived from Indian music and is based upon a high volume C drone played by Harrison on a tamboura.[69] Much of the backing track consists of a series of prepared tape loops, stemming from Lennon's and McCartney's interest in and experiments with magnetic tape and musique concrète techniques at that time. According to the Beatles' session chronicler Mark Lewisohn,[70] Lennon and McCartney prepared a series of loops at home, and these then were added to the pre-recorded backing track. This was reportedly done live in a single take, with multiple tape recorders running simultaneously, some of the longer loops extending out of the control room and down the corridor. Lennon's processed lead vocal was another innovation. Always in search of ways to enhance or alter the sound of his voice, he gave a directive to EMI engineer Geoff Emerick that he wanted to sound like he was the Dalai Lama singing from the top of a high mountain.[71] Emerick solved the problem by routing a signal from the recording console into the studio's Leslie speaker, giving Lennon's vocal its ethereal, filtered quality (Emerick was later reprimanded by the studio's management for doing this).

Cover art and title

The cover illustration was created by German-born bassist and artist Klaus Voormann, one of the Beatles' oldest friends from their days at the Star-Club in Hamburg. Voormann's illustration, part line drawing and part collage, included photographs by Robert Whitaker, who also took the back cover photographs and many other images of the group between 1964 and 1966, such as the infamous "butcher cover" for Yesterday and Today. Voormann's own photo as well as his name (Klaus O. W. Voormann) is worked into Harrison's hair on the right-hand side of the cover. In the Revolver cover appearing in his artwork for Anthology 3, he replaced this image with a more recent photo. Harrison's Revolver image was seen again on his single release of "When We Was Fab" along with an updated version of the same image. Voorman went on to play bass with Manfred Mann, and later on various post-Beatles solo albums.

The title "Revolver", like "Rubber Soul" before it, is a pun, referring both to a kind of handgun as well as the "revolving" motion of the record as it is played on a turntable. The Beatles had a difficult time coming up with this title. According to Barry Miles in his book Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now, the title that the four had originally wanted was Abracadabra, until they discovered that another band had already used it. After that, opinion split: Lennon wanted to call it Four Sides of the Eternal Triangle and Starr jokingly suggested After Geography, playing on The Rolling Stones' recently released Aftermath LP. Other suggestions included Magic Circles, Beatles on Safari, Pendulum, and finally, Revolver, whose wordplay was the one that all four agreed upon. The title was chosen while the band were on tour in Germany late June 1966. They spent much of their time in their hotels in Munich, in a special train between Munich, Essen and Hamburg and in their Hotel Tremsbüttel outside Hamburg. The name Revolver was finally selected while in the Hamburg hotel, as drafts prove.[72]

The Beatles' tour of Asia did not feature any songs from that album, and neither did the subsequent last tour. This was a further indication of how far their studio recordings had diverged from what they were playing live.

Release

Revolver was released in the United Kingdom on 5 August 1966 and on 8 August in the United States.[73] "Eleanor Rigby" was released as a double A-side with "Yellow Submarine". It maintained the number one position in the UK for four weeks during August and September.[74]

According to Rodriguez, Revolver's release was not the significant media event that Sgt. Pepper's was the following year.[15] There was no accompanying press buildup or conjecture regarding what the group was to offer. To the contrary, the album was "overshadowed" during a period of controversy following the negative reaction in the US to Lennon's remarks about the Beatles being "more popular than Jesus".[75]

The original North American LP release of Revolver, the band's tenth on Capitol Records and twelfth US album, marked the last time Capitol would release an altered UK Beatles album for the North American market. As three of its tracks – "I'm Only Sleeping", "And Your Bird Can Sing" and "Doctor Robert" – had been used for the earlier Yesterday and Today Capitol compilation, they were simply removed in the North American version, yielding an 11 track album instead of the UK version's 14 and shortening the time to 28:20. This resulted in there being only two songs with Lennon as the principal songwriter, with three by Harrison and the rest by McCartney. When the Beatles resigned with EMI in January 1967, their contract stipulated that Capitol could no longer alter the track listings of their albums.[76]

The album's 30 April 1987 release on CD standardised the track listing to the original UK version. Having been available only as an import in the US in the past, the 14-track UK version of the album was also issued domestically in the US on LP and cassette on 21 July 1987.

In 2014, the Capitol version of the album was issued on CD for the first time as part of The Beatles' The U.S. Albums boxed set as well as in an individual release.

Reception

| Retrospective reviews | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| Allmusic | |

| The A.V. Club | A+[78] |

| Blender | |

| Consequence of Sound | |

| The Daily Telegraph | |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Paste | 100/100[83] |

| Pitchfork Media | 10/10[84] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Sputnikmusic | 5/5[86] |

The music journalist Richard Goldstein, writing a contemporary review for The Village Voice, describes Revolver as "a revolutionary record", stating: "it seems now that we will view this album in retrospect as a key work in the development of rock and roll into an artistic pursuit".[87] In a 1967 article for Esquire, the author Robert Christgau called Revolver "twice as good and four times as startling as Rubber Soul, with sound effects, Oriental drones, jazz bands, transcendentalist lyrics, all kinds of rhythmic and harmonic surprises, and a filter that made John Lennon sound like God singing through a foghorn."[88]

According to MacDonald, with Revolver the Beatles "had initiated a second pop revolution – one which while galvanising their existing rivals and inspiring many new ones, left all of them far behind."[2] Rob Sheffield, writing in The Rolling Stone Album Guide (2004), said that the album found the Beatles "at the peak of their powers, competing with one another because nobody else could touch them", and concluded that, "these days, Revolver has earned its reputation as the best album the Beatles ever made, which means the best album by anybody."[85] In the Encyclopedia of Popular Music (2006), Colin Larkin wrote that the album was wide-ranging with Harrison's sardonic "Taxman", melancholic ballads by McCartney, and Lennon's drug-inspired songs such as "Tomorrow Never Knows", which "has been described as the most effective evocation of a LSD experience ever recorded."[82] PopMatters said in a 2007 review that the album had "the individual members of the greatest band in the history of pop music peaking at the exact same time".[89]

Legacy

Revolver invented musical expressions and initiated trends and motifs that would chart the path not only of the Beatles and a cultural epoch, but of the subsequent history of rock and roll as well.[90]

—Russell Reising

According to Rodriguez, whereas Sgt. Pepper has been routinely identified as the Beatles' greatest album – indeed, as arguably the finest rock album – Revolver has consistently contested and often surpassed it in lists of the group's best work.[91] He characterises Revolver as "the Beatles' artistic high-water mark", and notes that unlike Sgt. Pepper, it was the product of a collaborative effort, with "the group as a whole being fully vested in creating Beatle music".[15] In Riley's view, Sgt. Pepper is the Beatles' most notorious record for the wrong reasons – a flawed masterpiece that can only echo the strength of Revolver."[92] In the opinion of the musicologist Russell Reising: "However one defines and wherever on ranks Revolver, no one can deny that Revolver's impact was, by any standard of measurement, massive and transformative."[90]

Rodriguez praises Martin and Emerick's contribution to the album, suggesting that their talents were as essential to its success as the Beatles'.[93] He describes Revolver as the album that marks the group's waning interest in live performance "in favor of creating soundscapes without limitation".[94] In his opinion, whereas most contemporary music acts shy away from attempting a concept album in the vein of Sgt. Pepper, Revolver's "eclectic collection of diverse songs" continues to influence modern popular music.[94] According to the music critic Jim DeRogatis, Revolver represents a relic "of the first era of psychedelic rock and shining testaments to what can be accomplished in the recording studio when folks are fuelled on the potent drug of rampant imagination."[95] In the opinion of the musicologist Russell Reising, "Revolver remains a haunting, soothing, confusing, grandly complex and ambitious statement about the possibilities of popular music."[96]

In 1997 Revolver was named the third greatest album of all time in a Music of the Millennium poll conducted in the United Kingdom by HMV Group, Channel 4, The Guardian and Classic FM. In 2000 Q magazine placed it at number 1 in its list of the 50 Greatest British Albums Ever.[97] In 2001, the TV network VH1 named it the greatest album of all time, a position it also achieved in the Virgin All Time Top 1,000 Albums.[98] In 2003, Rolling Stone magazine ranked Revolver third on its list of the "500 Greatest Albums of All Time".[99] In 2006 the album was chosen by Time magazine as one of the 100 best albums of all time.[100] In 2006, Guitar World readers chose it as the 10th best guitar album of all time.[101] In 2010, Revolver was named the best pop album of all time by the official newspaper of the Holy See, L'Osservatore Romano.[102] In 2013, Entertainment Weekly named Revolver the greatest album of all time.[103]

Track listing

All tracks are written by Lennon–McCartney, except "Taxman", "Love You To" and "I Want to Tell You", which were composed by George Harrison[104]

| No. | Title | Lead vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Taxman" | Harrison | 2:39 |

| 2. | "Eleanor Rigby" | McCartney | 2:08 |

| 3. | "I'm Only Sleeping" | Lennon | 3:02 |

| 4. | "Love You To" | Harrison | 3:01 |

| 5. | "Here, There and Everywhere" | McCartney | 2:26 |

| 6. | "Yellow Submarine" | Starr | 2:40 |

| 7. | "She Said She Said" | Lennon | 2:37 |

| No. | Title | Lead vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8. | "Good Day Sunshine" | McCartney | 2:10 |

| 9. | "And Your Bird Can Sing" | Lennon | 2:02 |

| 10. | "For No One" | McCartney | 2:01 |

| 11. | "Doctor Robert" | Lennon | 2:15 |

| 12. | "I Want to Tell You" | Harrison | 2:30 |

| 13. | "Got to Get You into My Life" | McCartney | 2:31 |

| 14. | "Tomorrow Never Knows" | Lennon | 2:57 |

Charts

| Chart | Year | Peak position |

|---|---|---|

| UK Albums Chart[105] | 1966 | 1 |

| Billboard 200 Pop Albums | ||

| Australian Albums Chart |

Chart succession

Certifications

† BPI certification awarded only for sales since 1994.[5] |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Personnel

According to Mark Lewisohn:[70]

- The Beatles

- John Lennon – lead, acoustic and rhythm guitars, lead, harmony and backing vocals, piano, Hammond organ and harmonium, tape loops and sound effects, cowbell, tambourine, maracas, handclaps, finger snaps

- Paul McCartney – lead, acoustic and bass guitars, lead, harmony and backing vocals, piano, clavichord, tape loops, sound effects, handclaps, finger snaps

- George Harrison – lead, acoustic and rhythm guitars, bass, lead, harmony and backing vocals, sitar, tamboura, sound effects, maracas, tambourine, handclaps, finger snaps

- Ringo Starr – drums, tambourine, maracas, handclaps, finger snaps, lead vocals on "Yellow Submarine"

- Additional musicians and production staff

- Anil Bhagwat – tabla on "Love You To"

- Alan Civil – French horn on "For No One"

- Brian Jones – background vocals on "Yellow Submarine" (uncredited)

- Donovan – background vocals on "Yellow Submarine" (uncredited)

- Geoff Emerick – recording and mixing engineer; tape loops of the marching band on "Yellow Submarine"

- George Martin – producer; mixing engineer; piano on "Good Day Sunshine" and "Tomorrow Never Knows"; Hammond organ on "Got to Get You into My Life"; tape-loops of the marching band on "Yellow Submarine"

- Mal Evans – bass drum and background vocals on "Yellow Submarine"

- Marianne Faithfull – background vocals on "Yellow Submarine" (uncredited)

- Neil Aspinall – background vocals on "Yellow Submarine" (uncredited)

- Pattie Boyd – background vocals on "Yellow Submarine" (uncredited)

- Tony Gilbert, Sidney Sax, John Sharpe, Jurgen Hess – violins; Stephen Shingles, John Underwood – violas; Derek Simpson, Norman Jones – cellos: string octet on "Eleanor Rigby", orchestrated and conducted by George Martin (uncredited, with Paul McCartney)

- Eddie Thornton, Ian Hamer, Les Condon – trumpet; Peter Coe, Alan Branscombe – tenor saxophone: horn section on "Got To Get You Into My Life" orchestrated and conducted by George Martin (uncredited, with Paul McCartney)

Notes

- ^ Lennon later claimed to have written 70 percent of the lyrics, which McCartney refutes, stating that Lennon contributed "about half a line".[30]

- ^ McCartney's initial working name for the clergyman was Father McCartney, but he changed it to Father McKenzie after having found the name in a telephone directory.[36] His original choice for a title was "Miss Daisy Hawkins", but he changed it in favour of a name derived from the Beatles' Help! costar Eleanor Bron and a clothing shop he noticed while in Bristol with his then girlfriend, Jane Asher.[34] A person named Eleanor Rigby is buried at St. Peter Church Cemetery, in Liverpool's Woolton, near McCartney's home suburb of Allerton.[34]

- ^ Rolling Stone writes: "['Here, There and Everywhere''s] chord sequence bears Brian Wilson's influence, ambling through three related keys without ever fully settling into one, and the modulations – particularly the one on the line 'changing my life with a wave of her hand' – deftly underscore the lyrics, inspired by McCartney's girlfriend, actress Jane Asher."[45]

- ^ "Here, There and Everywhere" was the last song that McCartney wrote for next five months.[50]

- ^ "Yellow Submarine" was an enormous commercial success in the UK, where it topped the singles chart soon after its release in August 1966.[55]

- ^ According to Riley, "at the core of Lennon's pain is a bottomless sense of abandonment", a theme that Lennon would return to in late 1966 with "Strawberry Fields Forever".[56]

References

- ^ Walter Everett

- ^ a b MacDonald 2005, p. 192.

- ^ "Beatles". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time: The Beatles, 'Revolver'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ^ a b "Beatles albums finally go platinum". British Phonographic Industry. BBC News. 2 September 2013. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ a b c Rodriguez 2012, p. 4.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, p. 5.

- ^ a b Rodriguez 2012, p. 7.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, p. 3.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, p. 10.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, pp. 10–15.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, pp. 12–14.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b c Rodriguez 2012, p. xii.

- ^ a b Rodriguez 2012, p. xiii.

- ^ a b c Womack 2007, p. 139.

- ^ a b Womack 2007, p. 136.

- ^ a b Womack 2007, p. 135.

- ^ Riley 1988, p. 182.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 48: treated with heavy compression and ADT; Riley 1988, p. 183: "angry" and "poisoned with acridity".

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 49.

- ^ a b Everett 1999, p. 48.

- ^ Riley 1988, p. 183.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, p. 17.

- ^ Womack 2007, p. 137: among the Beatles' "most fully realized songs"; Womack 2007, p. 138: "narrative about the perils of loneliness".

- ^ Womack 2007, p. 138.

- ^ Womack 2007, pp. 137–139.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 51.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 51: McCartney states that Lennon contributed "about half a line"; MacDonald 2005, p. 204: Lennon claimed to have written 70 percent of the lyric.

- ^ MacDonald 2005, p. 203: string octet arranged by Martin; Womack 2007, p. 137: Martin drew inspiration from Bernard Herrmann.

- ^ Everett 1999, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 53.

- ^ a b c MacDonald 2005, p. 203.

- ^ a b Riley 1988, p. 185.

- ^ MacDonald 2005, pp. 203–204.

- ^ a b MacDonald 2005, p. 202.

- ^ Gould 2007, p. 353.

- ^ a b Everett 1999, pp. 50–51.

- ^ a b MacDonald 2005, p. 194.

- ^ a b Everett 1999, p. 40.

- ^ Everett 1999, pp. 40, 66.

- ^ a b c d e Womack 2007, p. 140.

- ^ a b Riley 1988, p. 186.

- ^ "100 Greatest Beatles Songs: 'Here, There and Everywhere'". Rolling Stone. 19 September 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ^ Riley 1988, p. 186: double-tracked vocals; Womack 2007, p. 140: varispeeding.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 60.

- ^ Riley 1988, p. 187.

- ^ Everett 1999, pp. 59–60.

- ^ a b Everett 1999, p. 62.

- ^ a b c Womack 2007, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Womack 2007, p. 141.

- ^ Riley 1988, pp. 187–188.

- ^ a b c d e Riley 1988, p. 188.

- ^ Womack 2007, p. 142.

- ^ Riley 1988, p. 190.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 66: the second time that a Beatles arrangement utilised a shifting metre; Riley 1988, p. 189: shifting metre.

- ^ Everett 1999, pp. 64–65.

- ^ a b MacDonald 2005, p. 211.

- ^ MacDonald 2005, pp. 211–212.

- ^ Riley 1988, pp. 190–191.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 46.

- ^ MacDonald 2005, p. 199.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 39, track 3.

- ^ BBC News 2002.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 190.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 39, tracks 4–5.

- ^ Harry 2004, p. 3.

- ^ Peter Lavezzoli. The Dawn of Indian Music in the West. Bhairavi. The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc. New York 2006. ISBN 0-8264-1815-5 ISBN 978-0826418159 2006. p175

- ^ a b Lewisohn 2004, pp. 70–85.

- ^ MacDonald 2005, p. 191.

- ^ Irvin.

- ^ Lewisohn 1992, pp. 350–351.

- ^ MacDonald 2005, p. 205.

- ^ MacDonald 2005, p. 213: Lennon's remarks about the Beatles being "more popular than Jesus"; Rodriguez 2012, p. xii: Revolver was "overshadowed" during a period of controversy.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, p. 6.

- ^ Revolver at AllMusic

- ^ Klosterman, Chuck (8 September 2009). "Chuck Klosterman Repeats The Beatles". The A.V. Club. Chicago. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ Coplan, Chris (20 September 2009). "Album Review: The Beatles – Revolver [Remastered]". Consequence of Sound. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ McCormick, Neil (7 September 2009). "The Beatles – Revolver, review". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ^ a b Larkin, Colin (2006). Encyclopedia of Popular Music. Vol. 1. Muze. p. 489. ISBN 0195313739.

- ^ "The Beatles: The Long and Winding Repertoire". 8 September 2009. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Plagenhoef, Scott (9 September 2009). "The Beatles – Revolver". Pitchfork.com. Retrieved 22 June 2012.

- ^ a b Sheffield, Rob; et al. (2004). Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon & Schuster. pp. 51, 53. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Campbell, Hernan M. (27 February 2012). "Review: The Beatles – Revolver". Sputnikmusic. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ^ Reising 2002a, p. 7.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (December 1967). "Columns: December 1967". Esquire. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ Medsker 2007.

- ^ a b Reising 2002a, p. 11.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, pp. x–xii.

- ^ Riley 1988, p. 203.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, pp. xii–xiii.

- ^ a b Rodriguez 2012, p. xiv.

- ^ DeRogatis, Jim (2003). Milk It: Collected Musings on the Alternative Music Explosion of the '90s. Da Capo Press. p. 352. ISBN 978-0-306-81271-2.

- ^ Reising 2002a, p. 1.

- ^ Reising 2002a, p. 2.

- ^ Reising 2002a, p. 3.

- ^ Levy 2005, p. 14.

- ^ Tyrangiel & Light 2006.

- ^ "100 Greatest Guitar Albums". Guitar World. October 2006. A copy can be found at "Guitar World's 100 Greatest Guitar Albums Of All Time – Rate Your Music". rateyourmusic.com. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- ^ Wakin, Daniel J. (14 February 2010). "From the Pope to Pop: Vatican's Top 10 List". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- ^ "10 All-Time Greatest Albums from EW". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ^ Lewisohn 1992, pp. 352–354.

- ^ "Chart Stats – The Beatles – Revolver". chartstats.com. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2009 Albums" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ "British album certifications – The Beatles – Revolver". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 15 September 2013. Select albums in the Format field. Select Platinum in the Certification field. Type Revolver in the "Search BPI Awards" field and then press Enter.

- ^ "Canadian album certifications – The Beatles – Revolver". Music Canada. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ "American album certifications – Beatles, The – Revolver". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

Bibliography

- BBC News (15 February 2002). "'Revolver' by the Beatles, 1966". BBC News. Retrieved 20 November 2007.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Everett, Walter (1999). The Beatles as Musicians: Revolver Through the Anthology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512941-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gilliland, John (1969). "The Rubberization of Soul: The great pop music renaissance" (audio). Pop Chronicles. Digital.library.unt.edu.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gould, Jonathan (2007). Can't Buy Me Love: The Beatles, Britain and America (First Paperback ed.). Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-307-35338-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harry, Bill (2004). The Ringo Starr Encyclopedia. Virgin Books. ISBN 0-7535-0843-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Irvin, Jim. "Different Strokes". Mojo.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Levy, Joe, ed. (2005). Rolling Stone's 500 Greatest Albums of All Time (First Paperback ed.). Wenner Books. ISBN 978-1-932958-61-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lewisohn, Mark (2004) [First published 1988]. The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions: The Official Story of the Abbey Road Years 1962–1970. Hamlyn. ISBN 0-681-03189-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lewisohn, Mark (1992). The Complete Beatles Chronicle:The Definitive Day-By-Day Guide To The Beatles' Entire Career (2010 ed.). Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-56976-534-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - MacDonald, Ian (2005). Revolution in the Head: The Beatles' Records and the Sixties (3rd ed.). Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-55652-733-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Medsker, David (2007). "The Beatles: Revolver — PopMatters Music Review". PopMatters. Retrieved 19 November 2007.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Miles, Barry (1997). Paul McCartney: Many Years From Now (1st Hardcover ed.). Henry Holt & Company. ISBN 978-0-8050-5248-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Riley, Tim (1988). Tell Me Why: The Beatles: Album By Album, Song By Song, The Sixties And After. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-55061-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Reising, Russell (2002a). "Introduction: 'Of the beginning'". In Reising, Russell (ed.). 'Every Sound There Is': The Beatles' Revolver and the Transformation of Rock and Roll. Ashgate Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-0-754-60557-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rodriguez, Robert (2012). Revolver: How the Beatles Reimagined Rock'n'Roll. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 978-1-617-13009-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tyrangiel, Josh; Light, Alan (13 November 2006). "The All-Time 100 Albums". Time. Retrieved 20 November 2007.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Unterberger, Richie. "Here, There and Everywhere review". Allmusic. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- Womack, Kenneth (2007). Long and Winding Roads: The Evolving Artistry of the Beatles. Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-1746-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Pages with empty short description

- 1966 albums

- Albums produced by George Martin

- Albums recorded at Abbey Road Studios

- Albums arranged by George Martin

- Albums arranged by Paul McCartney

- Albums conducted by George Martin

- Albums conducted by Paul McCartney

- Albums with cover art by Klaus Voormann

- Albums certified multi-platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America

- Albums certified platinum by the British Phonographic Industry

- The Beatles albums

- Capitol Records albums

- Counterculture of the 1960s

- English-language albums

- Grammy Hall of Fame Award recipients

- Parlophone albums

- Psychedelic rock albums