Total war: Difference between revisions

m →Development of the concept of Total War: dab Native Americans |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|Conflict in which all of a nation's resources are deployed}} |

|||

:''This article is about total warfare. For the computer game series see [[Total War]]''. |

|||

{{Other uses}} |

|||

[[Image:USPosterFoodIsAWeapon.jpg|thumb|right|250px|A [[United States|US]] poster produced during [[World War II]]]] |

|||

{{EngvarB|date=May 2023}} |

|||

'''Total war''' is a 20th century term to describe a [[war]] in which [[country|countries]] or [[nation|nations]] use all of their [[resource|resources]] to destroy another organized country's or nation's ability to engage in [[war]]. The practice of total war has been in use for [[century|centuries]], but it was only in the middle to late [[nineteenth century]] that total war was recognized as a separate class of [[warfare]]. |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=May 2023}} |

|||

[[File:Cyprian War.jpg|thumb|Ruins of [[Warsaw Insurgents Square (Warsaw)|Warsaw's Napoleon Square]] in the aftermath of [[World War II]]]] |

|||

{{History of war}} |

|||

'''Total war''' is a type of [[war]]fare that includes any and all [[civilian]]-associated resources and infrastructure as [[legitimate military target]]s, mobilises all of the resources of society to fight the war, and gives priority to warfare over [[non-combatant]] needs. |

|||

==Development of the concept of Total War== |

|||

The concept of total war is often traced back to [[Carl von Clausewitz]], but Clausewitz was actually concerned with the related philosophical concept of [[absolute war]], a war free from any political constraints, which Clausewitz held was impossible. The two terms, absolute war and total war, are often confused. Christopher Bassford, professor of strategy at the [[National War College]], describes the difference, "It is also important to note that Clausewitz's concept of absolute war is quite distinct from the later concept of 'total war.' Total war was a prescription for the actual waging of war typified by the ideas of General [[Erich von Ludendorff]], who actually assumed control of the German war effort during World War One. Total war in this sense involved the total subordination of politics to the war effort—an idea Clausewitz emphatically rejected—and the assumption that total victory or total defeat were the only options. Total war involved no suspension of the effects of time and space, as did Clausewitz's concept of the absolute"[http://www.clausewitz.com/CWZHOME/CWZSUMM/CWORKHOL.htm] |

|||

The term has been defined as "A war that is unrestricted in terms of the weapons used, the [[Territory (country subdivision)|territory]] or [[combatant]]s involved, or the objectives pursued, especially one in which the [[law of war|laws of war]] are disregarded."<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803105038425 |title=Total war |work=Oxford Reference |access-date=3 March 2022}}</ref> |

|||

Indeed, it is General Erich von Ludendorff during the [[World War I]] (and in his 1935 book "Total War") who first reversed the formula of Clausewitz, calling for total war- the complete mobilization of all resources, including policy and social systems, to the winning of war. |

|||

In the mid-19th century, scholars identified total war as a separate class of warfare. In a total war, the differentiation between combatants and non-combatants diminishes due to the capacity of opposing sides to consider nearly every human, including non-combatants, as resources that are used in the [[war effort]].<ref>{{cite journal |first=Edward |last=Gunn |title=The Moral Dilemma of Atomic Warfare |journal=Aegis: The Otterbein College Humanities Journal |date=Spring 2006 |page=[http://www.otterbein.edu/Aegis/Aegis_2006.pdf#page=67 67]}} NB Gunn cites this Wikipedia article as it was on {{diff|Total war|pref|24038262|27 September 2005}}, but on only for the text of the song "The Thing-Ummy Bob".</ref> |

|||

There are several reasons for changing concept and recognition of total war in the nineteenth century. The main reason is [[Industrial Revolution|industrialization]]. As countries' natural and capital resources grew, it became clear that some forms of [[conflict]] demanded more resources than others. For example, if the [[United States]] were to subdue a [[Native Americans in the United States|Native American]] [[tribe]] in an extended campaign lasting years, it still took much less resources than waging a month of war during the [[American Civil War]]. Consequently, the greater cost of warfare became evident. An industrialized nation could distinguish and then choose the intensity of warfare that it wished to engage in. |

|||

==Characteristics== |

|||

Additionally, this is the time when warfare was becoming more [[Mechanization|mechanized]]. A [[factory]] in a [[city]] would have more to do with warfare than it did before. The factory itself would become a target, because it contributed to the war effort. It follows as well that the factory's workers would also be targets. |

|||

Total war is a concept that has been extensively studied by scholars of conflict and war. One of the most notable contributions to this field of research is the work of Stig Förster, who has identified four dimensions of total war: total purposes, total methods, total mobilisation, and total control. Tiziano Peccia has built upon Förster's work by adding a fifth dimension of "total change." Peccia argues that total war not only has a profound impact on the outcome of the conflict but also produces significant changes in the political, cultural, economic, and social realms beyond the end of the conflict. As Peccia puts it, "total war is an earthquake that has the world as its epicenter."<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.conflittologia.it/rivista-n-25/|title=Rivista n.25 – Rivista Italiana di Conflittologia|date=1 May 2015}}</ref><ref>Peccia, T. (2015), Guerra Totale: interpretazione delle quattro dimensioni di Stig Förster ed il radicalecambiamento della società post-conflitto, Rivista italiana di conflittologia, pp. 51–65.</ref> |

|||

The four dimensions of total war identified by Förster are: |

|||

There is no single definition of total war, except that there is general agreement among historians that the [[First World War]] and [[Second World War]] were both examples. A large number of historians consider the [[American Civil War]] to be the earliest example{{ref|civilwar}}, some consider the wars of German unification the first, and others pick other starting points. Since the concept emerged gradually, however, there is no one correct answer. |

|||

1) Total purposes: The aim of continuous growth of the power of the parties involved and hegemonic visions. |

|||

Thus, definitions do vary, but most hold to the spirit offered by Roger Chickering's definition ''Total War: The German and American Experiences, 1871-1914'':"Total war is distinguished by its unprecedented intensity and extent. Theaters of operations span the globe; the scale of battle is practically limitless. Total war is fought heedless of the restraints of morality, custom, or international law, for the combatants are inspired by hatreds born of modern ideologies. Total war requires the mobilization not only of armed forces but also of whole populations. The most crucial determinant of total war is the widespread, indiscriminate, and deliberate inclusion of civilians as legitimate military targets. " |

|||

2) Total methods: Similar and common methodologies among countries that intend to increase their spheres of influence. |

|||

==Consequences of Total War== |

|||

3) Total mobilisation: Inclusion in the conflict of parties not traditionally involved, such as women and children or individuals who are not part of the armed bodies. |

|||

The most identifiable consequence of total war in modern times has been the inclusion of [[civilian|civilians]] and civilian infrastructure as targets in destroying a country's ability to engage in war. The targeting of civilians developed from two distinct [[theory|theories]]. The first theory was that if enough civilians were killed, factories could not function. The second theory was that if civilians were killed, the country would be so demoralized that it would have no ability to wage further war. |

|||

4) Total control: Multisectoral centralisation of the powers and orchestration of the activities of the countries in a small circle of dictators or oligarchs, with cross-functional control over education and culture, media/propaganda, economic, and political activities. |

|||

Total war also resulted in the mobilization of the [[home front]]. [[Propaganda]] became a required component of total war in order to boost production and maintain [[morale]]. [[Rationing]] took place to provide more material for waging war. |

|||

Peccia's contribution of "total change" adds to this framework by emphasising the long-term effects of total war on society. |

|||

Another consequence was the expansion of the peace time [[military]]. A [[navy]] could not be built overnight, and it had to be large enough to fight any potential enemy. This led to the [[dreadnought]] arms race before [[World War I]]. To justify the huge expenditure, populations had to become accustomed to thinking of the most likely potential enemy, as an enemy, which helped to foster war hysteria and [[jingoism]]. Large standing [[army|armies]] for countries with land borders close to a potential enemy and strong navies for maritime powers were the only way to prevent defeat before the economy could be mobilized. |

|||

5) Total change: This includes changes in social attitudes, cultural norms, and political structures, as well as economic and technological developments. |

|||

==Total war and its precursors== |

|||

In Peccia's view, total war not only transforms the military and political landscape but also has far-reaching and long-time implications for society as a whole.<ref>https:// www.conflittologia.it/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Rivista-n-25-completa.pdf</ref><ref>Peccia, T. (2015), Guerra Totale: interpretazione delle quattro dimensioni di Stig Förster ed il radicalecambiamento della società post-conflitto, Rivista italiana di conflittologia, pp. 51–65.</ref> |

|||

=== The French Revolution === |

|||

Actions that may characterise the post-19th century concept of total war include: |

|||

The [[French Revolution]] has introduced some of the concepts of total war. The fledgling republic found itself threatened by the most powerful coalition of European nations to have been formed at that point in history. The only solution, in the eyes of the [[Jacobin]] government was to pour the nation's entire resources into an unprecedented war effort - this was the advent of the [[levée en masse]]. The following decree of the [[National Convention]] on [[August 23]], [[1794]] clearly demonstrates the enormity of the French war effort: |

|||

* [[Strategic bombing]], as during [[Strategic bombing during World War II|World War II]], the [[Korean War#Bombing of North Korea|Korean War]], and the [[Vietnam War]] (Operations [[Operation Barrel Roll|Barrel Roll]], [[Operation Rolling Thunder|Rolling Thunder]] and [[Operation Linebacker II|Linebacker II]]) |

|||

* [[Blockade]] and [[siege|sieging]] of population centres, as with the [[Allies of World War I|Allied]] [[Blockade of Germany (1914–1919)|blockade of Germany]] and the [[Siege of Leningrad]] during the [[Blockade of Germany (1914–1919)|First]] and [[Blockade of Germany (1939–45)|Second]] World Wars |

|||

* [[Scorched earth]] policy, as with the [[Sherman's March to the Sea|March to the Sea]] during the [[American Civil War]] and the Japanese "[[Three Alls Policy]]" during the [[Second Sino-Japanese War]] |

|||

* [[Commerce raiding]], [[tonnage war]], and [[unrestricted submarine warfare]], as with [[privateer]]ing, the German [[U-boat]] campaigns of the First and Second World Wars, and the United States [[Allied submarines in the Pacific War|submarine campaign against Japan]] during World War II |

|||

* [[Collective punishment]], pacification operations, and [[reprisal]]s against populations deemed hostile, as with the execution and deportation of suspected [[Communards]] following the fall of the 1871 [[Paris Commune]] or the German reprisal policy targeting [[Resistance during World War II|resistance movements]], insurgents, and [[Untermensch]]en such as in France (e.g. [[Maillé massacre]]) and [[Pacification actions in German-occupied Poland|Poland]] during World War II |

|||

* [[Industrial warfare]], as with all belligerents in their respective [[home front]]s during [[Home front during World War I|World War I]] and [[Home front during World War II|World War II]] |

|||

* The use of [[civilian]]s and [[Prisoner of war|prisoners of war]] as [[forced labour]] for [[military operation]]s, as with Japan, USSR and Germany's massive use of forced labourers of other nations during World War II (see [[Slavery in Japan]] and [[forced labour under German rule during World War II]])<ref>{{cite book |title=On the Road to Total War: The American Civil War and the German Wars of Unification, 1861–1871 (Publications of the German Historical Institute) |page=296 |date=22 August 2002 |publisher=[[German Historical Institute]] |isbn=978-0-521-52119-2}}</ref> |

|||

* Giving [[no quarter]] (i.e. take no prisoners), as with [[Hitler]]'s [[Commando Order]] during World War II |

|||

==Background== |

|||

"From this moment until such time as its enemies shall have been driven from the soil of the Republic all Frenchmen are in permanent requisition for the services of the armies. The young men shall fight; the married men shall forge arms and transport provisions; the women shall make tents and clothes and shall serve in the hospitals; the children shall turn linen into lint; the old men shall betake themselves to the public squares in order to arouse the courage of the warriors and preach hatred of kings and the unity of the Republic." |

|||

The phrase "total war" can be traced back to the 1935 publication of German general [[Erich Ludendorff]]'s World War I memoir, ''Der totale Krieg'' ("The total war"). Some authors extend the concept back as far as classic work of [[Carl von Clausewitz]], ''[[On War]]'', as "absoluter Krieg" ([[absolute war]]), even though he did not use the term; others interpret Clausewitz differently.<ref name="StrachanHerberg-Rothe2007">{{cite book|author1=Hew Strachan|author2=Andreas Herberg-Rothe|title=Clausewitz in the twenty-first century|url=https://archive.org/details/clausewitztwenty00stra|url-access=limited|year=2007|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-923202-4|pages=[https://archive.org/details/clausewitztwenty00stra/page/n78 64]–66}}</ref> Total war also describes the French "guerre à outrance" during the [[Franco-Prussian War]].<ref name="ChickeringFörster2003">{{cite book|author1=Roger Chickering|author2=Stig Förster|title=The shadows of total war: Europe, East Asia, and the United States, 1919–1939|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ne0rFJbWfdIC&pg=PA8|year=2003|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-81236-8|page=8}}{{Dead link|date=August 2023 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref><ref name="Taithe1999">{{cite book|author=Bertrand Taithe|title=Defeated flesh: welfare, warfare and the making of modern France|year=1999|publisher=Manchester University Press|isbn=978-0-7190-5621-5|page=35 and 73}}</ref><ref name="Förster2002">{{cite book|author=Stig Förster|title=On the Road to Total War: The American Civil War and the German Wars of Unification, 1861–1871|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Qm4o2vsMTdYC&pg=PA550|year=2002|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-52119-2|page=550}}</ref> |

|||

In his 24 December 1864 letter to his [[chief of staff]] during the [[American Civil War]], Union general [[William Tecumseh Sherman]] wrote the Union was "not only fighting hostile armies, but a hostile people, and must make old and young, rich and poor, feel the hard hand of war, as well as their organized armies," defending [[Sherman's March to the Sea]], the operation that inflicted widespread destruction of infrastructure in Georgia.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://cwnc.omeka.chass.ncsu.edu/items/show/144|title=Letter of William T. Sherman to Henry Halleck, December 24, 1864 |date=24 December 1864 |publisher=Civil War Era NC|access-date=28 March 2020}}</ref> |

|||

=== American Civil War === |

|||

[[United States Air Force]] General [[Curtis LeMay]] updated the concept for the [[nuclear age]]. In 1949, he first proposed that a total war in the nuclear age would consist of delivering the entire [[nuclear arsenal]] in a single overwhelming blow, going as far as "killing a nation".<ref>{{cite book|last=DeGroot|first=Gerard J.|title=The bomb: a life|year=2004|publisher=Harvard|location=Cambridge, Mass.|isbn=978-0-674-01724-5|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6VQCsAZpPrgC&q=the%20entire%20stockpile%20of%20atomic%20bombs%20in%20a%20single%20massive%20attack&pg=PA153|edition=1st Harvard University Press pbk.|page=153}}</ref> |

|||

US Army General [[William Tecumseh Sherman]]'s '[[Sherman's March to the Sea|March to the Sea]]' during the '''[[American Civil War]]''' destroyed the resources required for [[Confederate States of America|the South]] to make war. He is considered one of the first military commanders to deliberately and consciously use total war as a military tactic. |

|||

==History== |

|||

=== American Indian Wars === |

|||

===Middle Ages=== |

|||

Some historians consider the various American [[Indian War]]s fought after the civil war to be influenced by the 'Total War' style behavior of the Civil War leaders. The theory goes that the Union officers who devastated the South brought the same ideas to the West. Not so much in that the American populace was committed totally to the Indian war effort. Rather the idea is that the Indian's civilian population was considered a part of the Indians 'war machine' and therefore it was legitimate target of Union soldiers. |

|||

Written by academics at [[Eastern Michigan University]], the ''Cengage Advantage Books: World History'' textbook claims that while total war "is traditionally associated with the two global wars of the twentieth century... it would seem that instances of total war predate the twentieth century." They write: |

|||

{{blockquote|As an aggressor nation, the ancient Mongols, no less than the modern [[Nazi Germany|Nazis]], practiced total war against an enemy by organizing all available resources, including [[military personnel]], [[non-combatant]] [[workers]], [[Military intelligence|intelligence]], [[transport]], [[money]], and [[wikt:provision|provisions]].<ref>Janice J. Terry, James P. Holoka, Jim Holoka, George H. Cassar, Richard D. Goff (2011). "''[https://books.google.com/books?id=mBo-2D0TKUcC&pg=PA717 World History: Since 1500: The Age of Global Integration]''". Cengage Learning. p. 717. {{ISBN|978-1-111-34513-6}}</ref>}} |

|||

In particular the destruction of the [[American Bison]] was an attempt to destroy the food supply of many [[Plains Indian]]s such as the [[Sioux]] and thus destroy their way of life. There were also wholesale slaughters of civilian populations such as at [[Wounded Knee]]. |

|||

===18th and 19th centuries=== |

|||

On the other hand slaughtering of Indian civilians had been going on a long time before the civil war, as far back as the [[Pequot War]], [[King Philip's War]], the [[DeSoto]] expedition, and [[Christopher Columbus]]. |

|||

=== |

====Europe==== |

||

In his book, ''The First Total War: Napoleon's Europe and the Birth of Warfare as We Know it'', David A Bell, a [[French History]] professor at [[Princeton University]] argues that the [[French Revolutionary Wars]] introduced to mainland Europe some of the first concepts of total war, such as mass conscription.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Bell|first1=David A|title=The First Total War: Napoleon's Europe and the Birth of Warfare as We Know It|date=2007|publisher=Houghton Mifflin Harcourt|isbn=978-0-618-34965-4|edition=First|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Pw5jup_LyHAC|access-date=19 January 2017}}</ref><ref>{{Citation |last=Bell |first=David A. |title=The First Total War? The Place of the Napoleonic Wars in the History of Warfare |date=2023 |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/cambridge-history-of-the-napoleonic-wars/first-total-war-the-place-of-the-napoleonic-wars-in-the-history-of-warfare/065046D6425195228A731A91C357BA4B |work=The Cambridge History of the Napoleonic Wars |volume=2: Fighting the Napoleonic Wars|pages=665–681 |editor-last=Mikaberidze |editor-first=Alexander |publisher=Cambridge University Press |doi=10.1017/9781108278096.033 |isbn=978-1-108-41766-2 |editor2-last=Colson |editor2-first=Bruno}}</ref> He claims that the new republic found itself threatened by a powerful coalition of European nations and used the entire nation's resources in an unprecedented war effort that included [[levée en masse]] (mass conscription). By 23 August 1793, the French front line forces grew to some 800,000 with a total of 1.5 million in all services—the first time an army in excess of a million had been mobilised in Western history: |

|||

{{blockquote|From this moment until such time as its enemies shall have been driven from the soil of the Republic all Frenchmen are in permanent requisition for the services of the armies. The young men shall fight; the married men shall forge arms and [[logistics|transport provisions]]; the women shall make tents and clothes and shall serve in the hospitals; the children shall turn old lint into linen; the old men shall betake themselves to the public squares in order to arouse the courage of the warriors and preach hatred of kings and the unity of the Republic.}} |

|||

During the civil war ([[1850]]-[[1864]]) that followed the seccession of the [[Taiping Rebellion|Taiping Tianguo]] (Heavenly Kingdom of Perfect Peace) from the [[Qing dynasty|Qing empire]] the first instance of total war in modern China can be seen. Almost every citizen of the Taiping Tianguo was given military training and conscripted into the army to fight against the imperial forces. |

|||

[[File:SavenayDrownings.jpg|thumb|The drownings at [[Battle of Savenay|Savenay]] during the [[War in the Vendée]], 1793]] |

|||

During this conflict both sides tried to deprive each other of the resources to continue the war and it became standard practice to destroy agricultural areas, butcher the population of cities and in general exact a brutal price from captured enemy lands in order to drastically weaken the opposition's war effort. This war truly was total in that civilians on both sides participated to a significant extent in the war effort and in that armies on both sides waged war on the civilian population as well as military forces. In total between 20 and 50 million died in the conflict making it bloodier than the [[First World War]] and possibly bloodier than the [[Second World War]] as well if the upper end figures are accurate. |

|||

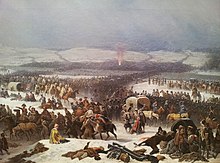

[[File:National Museum in Poznan - Przejście przez Berezynę.JPG|thumb|[[Napoleon]]'s retreat from Russia in 1812. Napoleon's ''[[Grande Armée]]'' had lost about half a million men.]] |

|||

During the [[French invasion of Russia|Russian campaign]] of 1812 the Russians retreated while destroying infrastructure and agriculture in order to effectively hamper the French and strip them of adequate supplies. In the campaign of 1813, Allied forces in the German theatre alone amounted to nearly one million whilst two years later in [[the Hundred Days]] a French decree called for the total mobilisation of some 2.5 million men (though at most a fifth of this was managed by the time of the French defeat at [[Battle of Waterloo|Waterloo]]). During the prolonged [[Peninsular War]] from 1808 to 1814 some 300,000 French troops were kept permanently occupied by, in addition to several hundred thousand Spanish, Portuguese and British regulars, an enormous and sustained guerrilla insurgency—ultimately French deaths would amount to 300,000 in the Peninsular War alone.<ref>{{cite journal | last = Broers | first = Michael | author-link = Michael Broers | date = 2008 | title = The Concept of 'Total War' in the Revolutionary – Napoleonic Period | journal = War in History | volume = 15 | number = 3 | pages = 247–268 | doi = 10.1177/0968344508091323| s2cid = 145549883 }}</ref> |

|||

=== World War I === |

|||

Almost the whole of [[Europe]] mobilized to conduct '''[[World War I]]'''. Young men were removed from production jobs, and were replaced by women. Rationing occurred on the home fronts. |

|||

The Franco-Prussian War was fought in breach of the recently signed [[First Geneva Convention|Geneva Convention of 1864]], when "European opinion increasingly expected that civilians and soldiers should be treated humanely in war".<ref>According to [https://francehistory.wordpress.com/2018/06/03/was-the-franco-prussian-war-a-modern-or-total-war/ Karine Varley, ''Was the Franco-Prussian War a Modern or Total War?'', 03/06/2018, History of Modern France at War], "the besieged cities, most notably [[Paris]], [[Strasbourg]], [[Metz]] and [[Belfort]] came closest to experiencing total war. German forces regularly bombarded civilian areas with the intention of damaging morale. In Paris, up to 400 shells a day were fired at civilian areas".</ref> |

|||

One of the features of Total War in Britain was the use of propaganda posters to divert all attention to the War on the home front. Posters were used to influence people's decision on what to eat, what occupations to take (Women were used as nurses and in munitions factories), and to change the attitude of support towards the war effort. |

|||

==== North America ==== |

|||

After the failure of the [[Battle of Neuve Chapelle]], the large British offensive in March [[1915]], the British Commander-in-Chief [[Field Marshal]] Sir [[John Denton Pinkstone French, 1st Earl of Ypres|John French]] claimed that it failed due to a lack of shells. This led to the [[Shell Crisis of 1915]] which brought down the [[Liberal Party (UK)|Liberal]] British government under the [[Prime Minister|Premiership]] of [[Henry Asquith]]. He formed a new coalition government dominated by Liberals and appointed [[Lloyd George]] as [[Minister of Munitions]]. It was a recognition that the whole economy would have to be geared for war if the Allies were to prevail on the Western Front. |

|||

The [[Sullivan Expedition]] of 1779 was an example of total warfare. As Native American and [[Loyalist (American Revolution)|Loyalist]] forces massacred American farmers, killed livestock and burned buildings in remote frontier areas, General [[George Washington]] sent General [[John Sullivan (general)|John Sullivan]] with 4,000 troops to seek "the total destruction and devastation of their settlements" in upstate New York. There was only one small battle as the expedition devastated "14 towns and most flourishing crops of corn." The Native Americans escaped to Canada where the British fed them; they remained there after the war.<ref>See [https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-20-02-0661 "From George Washington to Major General John Sullivan, 31 May 1779" National Archives]</ref><ref>Fischer, Joseph R. (1997) ''A Well-Executed Failure: The Sullivan Campaign against the Iroquois, July–September 1779'' Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press {{isbn|978-1-57003-137-3}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=Understanding U.S. Military Conflicts through Primary Sources |date=2016 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |page=149}}</ref> |

|||

[[Sherman's March to the Sea]] in the [[American Civil War]]—from 15 November 1864, through 21 December 1864—is sometimes considered to be an example of total war, for which Sherman used the term '''''hard war'''''. Some historians challenge this designation, as Sherman's campaign assaulted primarily military targets and Sherman ordered his men to spare civilian homes.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Caudill |first1=Edward |last2=Ashdown |first2=Paul |title=Sherman's March in Myth and Memory |year= 2009 |publisher=Rowman and Littlefield Publishers |isbn=978-1442201279 |pages=75–79}}</ref> |

|||

As young men left the farms for the front, domestic food production in Britain and Germany fell. In Britain the response was to import more food, which was done despite the German introduction of unrestricted submarine warfare, and to introduce rationing. The Royal Navy's blockade of German ports prevented Germany from importing food, and the Germans failed to introduce food rationing. German capitulation was hastened in 1918 by the worsening food crises in Germany. |

|||

=== |

===20th century=== |

||

====World War I==== |

|||

[[File:Bundesarchiv Bild 146-2008-0084, Belgien, Flandern, Ruinen.jpg|thumb|Damage and destruction of civilian buildings in Belgium, 1914]] |

|||

==== |

=====Air Warfare===== |

||

{{main|Air warfare in World War I}} |

|||

Bombing civilians from the air was adopted as a strategy for the first time in World War I, and a leading advocate of this strategy was [[Peter Strasser]] "Leader of Airships" (''Führer der Luftschiffe''; ''F.d.L.''). Strasser, who was chief commander of [[German Imperial Navy]] [[Zeppelin]]s during World War I, the main force operating German strategic bombing across Europe and the UK, saw bombing of civilians as well as military targets as an essential element of total war. He argued that causing civilian casualties and damaging domestic infrastructure served both as propaganda and as a means of diverting resources from the front line. |

|||

{{blockquote|We who strike the enemy where his heart beats have been slandered as 'baby killers' ... Nowadays, there is no such animal as a noncombatant. Modern warfare is [[total warfare]].|Peter Strasser<ref>Lawson, Eric; Lawson, Jane (1996). The first air campaign, August 1914 – November 1918. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press. pp. 79–80. {{ISBN|0-306-81213-4}}.</ref>}} |

|||

Before the onset of the [[Second World War]], the [[United Kingdom]] drew on its [[World War I|First World War]] experience to prepare legislation that would allow immediate mobilization of the economy for war, should future hostilities break out. |

|||

=====Propaganda===== |

|||

Rationing of most goods and services was introduced, not only for consumers but also for manufacturers. This meant that factories manufacturing products that were irrelevant to the war effort had more appropriate tasks imposed. All artificial light was subject to legal [[Blackout (wartime)|Blackout]]s. |

|||

{{main|Propaganda in World War I}} |

|||

One of the features of total war in Britain was the use of government [[propaganda]] posters to divert all attention to the war on the [[home front]]. Posters were used to influence public opinion about what to eat and what occupations to take, and to change the attitude of support towards the war effort. Even [[music hall]]s were used as propaganda, with propaganda songs aimed at recruitment.<ref>{{Cite web |date=August 8, 2014 |title=World War One: Music hall entertainers with the 'X factor' |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-27508148 |access-date=September 7, 2023 |website=BBC News}}</ref> |

|||

After the failure of the [[Battle of Neuve Chapelle]], the large British offensive in March 1915, the British Commander-in-Chief [[Field Marshal]] John French blamed the lack of progress on insufficient and poor-quality [[Shell (projectile)|artillery shells]]. This led to the [[Shell Crisis of 1915]] which brought down both the [[Liberal Party (UK)|Liberal]] government and [[Prime Minister of the United Kingdom|Premiership]] of [[H. H. Asquith]]. He formed a new coalition government dominated by Liberals and appointed [[David Lloyd George]] as [[Minister of Munitions]]. It was a recognition that the whole economy would have to be geared for war if the Allies were to prevail on the Western Front.{{Citation needed|date=March 2021}} |

|||

Not only were men and women conscripted into the armed forces from the beginning of the war (something which had not happened until the middle of World War I), but women were also conscripted as [[Land Girls]] to aid farmers and the [[Bevin Boys]] were conscripted to work down the coal mines. |

|||

[[Carl Schmitt]], a supporter of [[Nazi Germany]], wrote that total war meant "total politics"—authoritarian domestic policies that imposed direct control of the press and economy. In Schmitt's view the total state, which directs fully the mobilisation of all social and economic resources to war, is antecedent to total war. Scholars consider that the seeds of this total state concept already existed in the German state of World War I, which exercised full control of the press and other aspects economic and social life as espoused in the statement of state ideology known as the "[[Fascism#World War I and its aftermath (1914–1929)|Ideas of 1914]]".<ref name=demm>{{cite journal|title=Propaganda and Caricature in the First World War|journal=Journal of Contemporary History|volume=28|pages=163–192|doi=10.1177/002200949302800109|year=1993|last1=Demm|first1=Eberhard|s2cid=159762267}}</ref> |

|||

Huge casualties were expected in bombing raids, so children were evacuated from London and other cities en masse to the countryside for compulsory [[Billet|billeting]] in households. In the long term this was one of the most profound and longer lasting social consequences of the whole war for Britain. This is because it mixed up children with the adults of other classes. Not only did the middle and upper classes become familiar with the urban squalor suffered by working class children from the slums, but the children got a chance to see animals and the countryside for the first time and experience how the other half lived. Many went back to the cities with their social horizons broadened. |

|||

==== |

=====Rationing===== |

||

{{Main|Home front during World War I}} |

|||

As young men left the farms for the front, domestic food production in Britain and Germany fell. In Britain, the response was to import more food, which was done despite the German introduction of [[unrestricted submarine warfare]], and to introduce rationing. The Royal Navy's [[Blockade of Germany (1914–1919)|blockade of German ports]] prevented Germany from importing food and hastened German capitulation by creating a food crisis in Germany.<ref>Jürgen Kocka, ''Facing total war: German society, 1914–1918'' (1984).</ref> |

|||

Almost the whole of Europe and some of the European colonial empires mobilised soldiers. Rationing occurred on the home fronts. [[Bulgaria]] went so far as to mobilise a quarter of its population, or 800,000 people, a greater share of its population than any other country during the war. |

|||

In contrast [[Germany]] started the war under the concept of [[Blitzkrieg]]. It did not accept that it was in a total war until [[Joseph Goebbels]]' [[Sportpalast speech]] of [[18 February]] [[1943]]. For example, women were not conscripted into the armed forces. |

|||

====World War II==== |

|||

The commitment to the doctrine of the short war was a continuing handicap for the Germans; neither plans nor state of mind were adjusted to the idea of a long war until it was too late to help win the war. Germany's armament minister [[Albert Speer]], who assumed office in early 1942, rationalized German war production and eliminated the worst inefficiencies. Under his direction a threefold increase in armament production occurred and did not reach its peak until late 1944. To do this during the damage caused by the growing strategic Allied bomber offensive, is an indication of the degree of industrial under-mobilization in the earlier years. It was because the German economy through most of the war was substantially undermobilized that it was resilient under air attack. Civilian consumption was high during the early years of the war and inventories both in industry and in consumers' possession were high. These helped cushion the economy from the effects of bombing. Plant and machinery were plentiful and incompletely used, thus it was comparatively easy to substitute unused or partly used machinery for that which was destroyed. Foreign labour (much of it slave labour) was used to augmented German industrial labour which was under pressure by conscription into the ''[[Wehrmacht]]'' (Armed Forces). But these efforts ended in vain because of harsher bombings such as [[bombing of Dresden]] |

|||

The [[Second World War]] was the quintessential total war of modernity.<ref name="Fink">{{Cite book |last=Fink |first=George |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rOq4XV94wLsC |title=Stress of War, Conflict and Disaster |date=2010 |publisher=Academic Press |isbn=978-0-12-381382-4 |pages=227 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Donn |first=Hill |date=15 April 2014 |title=Total Victory Through Total War |url=https://publications.armywarcollege.edu/publication-detail.cfm?publicationID=131 |journal=United States War College Publications |pages=3, 19 |via=USAWC}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Rouhan |first=Michael |date=2022 |title=Did The Second World War, More So Than The First World War, Exemplify The Character Of 'Total War'? |url=https://www.mindef.gov.sg/oms/safti/pointer/documents/pdf/monthlyissue/oct2022.pdf |journal=Journal of the Singapore Armed Forces}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Chun Hong |first=Kelvin Yap |date=2023 |title=DID THE SECOND WORLD WAR, MORE SO THAN THE FIRST WORLD WAR, EXEMPLIFY THE CHARACTER OF 'TOTAL WAR'? |url=https://www.mindef.gov.sg/oms/safti/pointer/documents/pdf/monthlyissue/jan2023.pdf |journal=Journal of the Singapore Armed Forces}}</ref> The level of national mobilisation of resources on all sides of the conflict, the [[battlespace]] being contested, the scale of the [[army|armies]], [[navy|navies]], and [[air force]]s raised through [[conscription]], the active targeting of non-combatants (and non-combatant property), the general disregard for [[collateral damage]], and the unrestricted aims of the belligerents marked total war on an unprecedented and unsurpassed, multicontinental scale.<ref>Lizzie Collingham, ''Taste of war: World War II and the battle for food'' (Penguin, 2012).</ref> |

|||

==== |

=====Imperial Japan===== |

||

[[File:Founding Ceremony of the Hakko-Ichiu Monument.JPG|thumb|upright|Founding ceremony of the ''[[Hakkō ichiu]]'' Monument, promoting the unification of "the 8 corners of the world under one roof"]] |

|||

During the first part of the [[Shōwa era]], the government of [[Empire of Japan|Imperial Japan]] launched a string of policies to promote a total war effort [[Second Sino-Japanese War|against China]] and [[Pacific war|occidental powers]] and increase industrial production. Among these were the [[National Spiritual Mobilization Movement]] and the [[Taisei Yokusankai|Imperial Rule Assistance Association]].{{Citation needed|date=March 2021}} |

|||

The Soviet Union was a [[planned economy|command economy]] which already had an economic and legal system allowing the economy and society to be redirected into fighting a total war. The transportation of factories and whole labour forces east of the [[Urals]] as the Germans advanced across the USSR in 1941 was an impressive feat of planning. Only those factories which were useful for war production were moved due to the the total war commitment of the Soviet government. |

|||

The [[State General Mobilization Law]] had fifty clauses, which provided for government controls over civilian organisations (including [[labour union]]s), [[nationalisation]] of strategic industries, price controls and [[rationing]], and nationalised the [[news media]].<ref>Pauer, ''Japan's War Economy'', 1999 p. 13</ref> The laws gave the government the authority to use unlimited budgets to subsidise war production and to compensate manufacturers for losses caused by war-time mobilisation. Eighteen of the fifty articles outlined penalties for violators.{{Citation needed|date=March 2021}} |

|||

During the [[siege of Leningrad]], newly-built [[T-34 tank]]s were driven - unpainted due to a paint shortage - from the factory floor straight to the front. This came to symbolise the USSR's commitment to the [[Great Patriotic War]] and demonstrated the government's total war policy. |

|||

To improve its production, Imperial Japan used millions of [[slave labour]]ers<ref>Unidas, Naciones. ''World Economic And Social Survey 2004: International Migration'', p. 23</ref> and [[Slavery in Japan|pressed more than 18 million people]] in [[East Asia]] into forced labour.<ref>Zhifen Ju, "''Japan's atrocities of conscripting and abusing north China draftees after the outbreak of the Pacific war''", 2002, [http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+id0029) Library of Congress, 1992, "Indonesia: World War II and the Struggle For Independence, 1942–50; The Japanese Occupation, 1942–45"] Access date: 9 February 2007.</ref> |

|||

To encourage the Russian people to work harder, the [[communist]] government encouraged the people's love of the Motherland ''[[Rodina]]'' and even allowed the reopening of [[Russian Orthodox Church]]es as it was thought this would help the war effort. |

|||

=====United Kingdom===== |

|||

The ruthless movement of national groupings like the [[Volga German]] and later the [[Crimean Tatars]] (who Stalin thought might be sympathetic to the Germans) was a development of the conventional [[scorched earth]] policy. This was a more extreme form of [[internment]], implemented by both the UK government (for [[Axis Powers|Axis]] aliens and British [[Nazi]] sympathisers), and the US government (for [[Japanese internment in the United States]]). |

|||

{{main|United Kingdom home front during World War II}} |

|||

Before the onset of the Second World War, Great Britain drew on its First World War experience to prepare legislation that would allow immediate mobilisation of the economy for war, should future hostilities break out. Rationing of most goods and services was introduced, not only for consumers but also for manufacturers. This meant that factories manufacturing products that were irrelevant to the war effort had more appropriate tasks imposed. All artificial light was subject to legal [[Blackout (wartime)|blackouts]].<ref>Angus Calder, ''The People's War: Britain 1939–45'' (1969) [https://archive.org/details/peopleswarbritai00cald online]</ref> |

|||

{{Blockquote|..There is another more obvious difference from 1914. The whole of the warring nations are engaged, not only soldiers, but the entire population, men, women and children. The fronts are everywhere to be seen. The trenches are dug in the towns and streets. Every village is fortified. Every road is barred. The front line runs through the factories. The workmen are soldiers with different weapons but the same courage." |

|||

|source=[[Winston Churchill]] on the radio, June 18; and [[British House of Commons|House of Commons]] 20 August 1940:<ref>Winston Churchill ''[http://www.winstonchurchill.org/learn/speeches/speeches-of-winston-churchill/1940-finest-hour/113-the-few The Few] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140923061951/http://www.winstonchurchill.org/learn/speeches/speeches-of-winston-churchill/1940-finest-hour/113-the-few |date=23 September 2014 }}'' The Churchill Centre</ref>}} |

|||

Not only were men conscripted into the armed forces from the beginning of the war (something which had not happened until the middle of World War I), but women were also conscripted as [[Women's Land Army (World War II)|Land Girls]] to aid farmers and the [[Bevin Boys]] were conscripted to work down the coal mines. |

|||

==== Descent into barbarism ==== |

|||

Enormous casualties were expected in bombing raids, so [[Evacuations of civilians in Britain during the Second World War|children were evacuated from London and other cities en masse to the countryside]] for compulsory [[billet]]ing in households. In the long term this was one of the most profound and longer-lasting social consequences of the whole war for Britain.{{Citation needed|date=April 2022}} This is because it mixed up children with adults of other classes. Not only did the middle and upper classes become familiar with the urban squalor suffered by working class children from the [[slum]]s, but the children got a chance to see animals and the countryside, often for the first time, and experience rural life. |

|||

The suspension of many of the rules of war on the [[Eastern Front (WWII)|Eastern Front]] during World War II coupled with an escalation in criminal actions caused human misery on a scale never seen before. Nazi Germany engaged in wholesale slaughter of three million Soviet POWs, and over eleven million innocent civilians, including the genocide of the Jews of Europe that killed approximately six million people (see [[Holocaust]]). Many actions which ignored the rules of war were initiated or at least condoned by the authorities on both sides. They argued that in such a clash of ideology that any methods in a total war which achieved victory over the enemy were justified. <!--sources?--> |

|||

The use of statistical analysis, by a branch of science which has become known as [[Operational Research]] to influence military tactics, was a departure from anything previously attempted. It was a very powerful tool but it further dehumanised war particularly when it suggested strategies that were counter-intuitive. Examples, where statistical analysis directly influenced tactics include the work done by [[Patrick Blackett]]'s team on the optimum size and speed of convoys and the introduction of [[bomber stream]]s, by the [[Royal Air Force]] to counter the night fighter defences of the [[Kammhuber Line]]. |

|||

The suspension of many of the rules of war in the [[Pacific War|Pacific and Asian Theatres]] of World War II particularly in the Sino-Japanese conflict, [[Japanese war crimes|caused wide scale human misery]]. Many actions which ignored the rules of war were initiated or at least condoned by the Japanese authorities. |

|||

==== |

=====Nazi Germany===== |

||

{{see also|Reich Plenipotentiary for Total War}} |

|||

In 1935 [[General Ludendorff]] in the book ''Der Totale Krieg'' gave life to the term "Total War" in the German lexicon.{{sfn|Eriksson|2013}} However, being followers of the [[stab-in-the-back myth]], military and Nazi leadership believed that Germany hadn't lost World War I on the battlefield but solely on the [[Home front during World War I|home front]].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Overy |first1=Richard |title=War and Economy in the Third Reich |date=1994 |publisher=Clarendon Press |location=Oxford |pages=28–30|isbn=978-0198202905}}</ref> |

|||

Britain and Germany made a distinct attempt to destroy the other's ability to produce war materials. They did this by the use of [[strategic bombing]] campaigns upon each others' cities. When the United States entered the war, it executed similar campaigns against both Germany and Japan. |

|||

Therefore, [[Germany]] started the war under the concept which was later named [[blitzkrieg]]. Officially, it did not accept that it was in a total war until [[Joseph Goebbels]]' [[Sportpalast speech]] of 18 February 1943—in which the crowd was told "''Totaler Krieg – Kürzester Krieg''" ("Total War – Shortest War”.)<ref>Statement from the banner in Sportpalast, 18 February 1943, Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-J05235 / Schwahn / CC-BY-SA 3.0</ref> |

|||

==== Unconditional surrender ==== |

|||

[[File:Bundesarchiv Bild 183-J05235, Berlin, Großkundgebung im Sportpalast.jpg|thumb|left|Nazi rally on 18 February 1943 at the [[Berlin Sportpalast]]; the sign says "{{lang|de|Totaler Krieg – Kürzester Krieg}}" ("Total War – Shortest War").]] |

|||

After the United States entered World War II, President [[Franklin D. Roosevelt]] declared at [[Casablanca conference]] to the other Allies and the press that [[unconditional surrender]] was the objective of the war against the Axis Powers of Germany, Italy, and Japan. Prior to this declaration, the individual regimes of the Axis Powers could have negotiated an armistice similar to that at the end of World War I and then a conditional surrender when they perceived that the war was lost. The allied war aim of unconditional surrender inevitably increased the determination and the ferocity of the defence of the Axis powers when they knew the war was lost. |

|||

Goebbels and Hitler had spoken in March 1942 about Goebbels' idea to put the entire home front on a war footing. Hitler appeared to accept the concept, but took no action. Goebbels had the support of minister of armaments [[Albert Speer]], economics minister [[Walther Funk]] and [[Robert Ley]], head of the [[German Labour Front]], and they pressed Hitler in October 1942 to take action, but Hitler, while outwardly agreeing, continued to dither. Finally, after the holidays in 1942, Hitler sent his powerful personal secretary, [[Martin Bormann]], to discuss the question with Goebbels and [[Hans Lammers]], the head of the [[Reich Chancellery]]. As a result, Bormann told Goebbels to go ahead and draw up a draft of the necessary decree, to be signed in January 1943. Hitler signed the decree on 13 January, almost a year after Goebbels first discussed the concept with him. The decree set up a steering committee consisting of Bormann, Lammers, and General [[Wilhelm Keitel]] to oversee the effort, with Goebbels and Speer as advisors; Goebbels had expected to be one of the triumvirate. Hitler remained aloof from the project, and it was Goebbels and [[Hermann Göring]] who gave the "total war" radio address from the Sportspalast the next month, on the 10th anniversary of the [[Nazi seizure of power|Nazi's "seizure of power"]].<ref>[[Ralf Georg Reuth|Reuth, Ralph Georg]] (1993) ''Goebbels'' Translated by Krishna Winston. New York: Harcourt Brace. pp. 304, 309–313. {{isbn|0-15-136076-6}}</ref> |

|||

==Post World War II== |

|||

{{Blockquote|I ask you: Do you want total war? If necessary, do you want a war more total and radical than anything that we can even imagine today?|source=[[National Socialist|Nazi]] [[propaganda]] minister [[Joseph Goebbels]], 18 February 1943, in his [[Sportpalast speech]]'}} |

|||

There has been a cessation of large decisive wars between industrialized nations since the end of [[World War II]], because their ability to wage war on each other had become so destructive that the potential damage more than offset the advantages of any victory. With nuclear weapons, the fighting of a war became something that instead of taking years, and the full mobilisation of a country's resources such as in World War II, would instead take hours and was developed and maintained with relatively modest peace time defence budgets. By the end of the [[1950s]], the super-power rivalry resulted in the development of [[Mutually Assured Destruction|MAD (Mutually Assured Destruction)]] in which a war could destroy civilisation and would result in hundreds of millions of deaths in a world where, in the words of [[Edward Heath]], "''The dying will envy the dead''". |

|||

The commitment to the doctrine of the short war was a continuing handicap for the Germans; neither plans nor state of mind were adjusted to the idea of a long war until the failure of the [[Operation Barbarossa]]. A major strategic defeat in the [[Battle of Moscow]] forced Speer as armaments minister to nationalise German war production and eliminate the worst inefficiencies.<ref>A. S. Milward (1964) "The End of the Blitzkrieg". ''The Economic History Review'', New Series, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. 499–518.</ref> |

|||

As the tensions between industrialized nations have diminished, European continental powers have for the first time in 200 years started to question if conscription is still necessary. Many are moving back to the pre-Napoleonic ideas of having small professional armies. This is something which despite the experiences of the first and second world wars is a model which the English speaking nations had never abandoned during peace time, probably because they have never had a common border with a potential enemy with a large standing army. In Admiral [[John Jervis, 1st Earl of St Vincent|Jervis]]'s famous phrase, "''I do not say, my Lords, that the French will not come. I say only they will not come by sea''". |

|||

===== Canada ===== |

|||

The cessation of total war has not led to the end of war involving industrial nations, but a shift back to the limited wars of the type fought between the competing European powers for much of the [[19th century]] that could be summed up by the phrase [[The Great Game]]. During the [[Cold War]], wars between industrialized nations were fought by [[proxy war|proxy]] over national [[prestige (sociology)|prestige]], tactical strategic advantage or [[colonial]] and [[neocolonialism|neocolonial]] resources. Examples include the [[Korean War]], the [[Vietnam War]] and the [[Soviet invasion of Afghanistan]]. Since the end of the Cold War, some industrialised countries have been involved in a number of small wars with strictly limited strategic objectives which have motives closer to those of the colonial wars of the 19th century than those of total war; examples include the [[Australia]]n-led [[UN]] intervention in [[East Timor]], the [[NATO]] intervention in [[Kosovo]], the internal Russian conflict with [[Chechnya]], and the [[United States|American]]-led coalitions which invaded [[U.S. invasion of Afghanistan|Afghanistan]] and twice fought the [[Iraq]]i regime of [[Saddam Hussein]]. |

|||

{{Main|Conscription Crisis of 1944}} |

|||

In Canada early use of the term concerned whether or not the country was committing enough to mobilising its resources, rather than whether or not to target civilians of the enemy countries. During the early days of the Second World War, whether or not Canada was committed to a "total war effort" was point of partisan political debate between the governing [[Liberal Party of Canada|Liberals]] and the opposition [[Conservative Party of Canada (1867–1942)|Conservatives]]. The Conservatives elected as their national leader [[Arthur Meighen]], who had been the cabinet minister responsible for implementing [[Conscription Crisis of 1917|conscription during the First World War]], and advocated for conscription again. Prime Minister [[W.L. Mackenzie King]] argued that Canada could still be said to have a "total war effort" without conscription, and delivered nationally broadcast speeches to this effect 1942.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Canada and the war : manpower and a total war effort : national selective service : broadcast by Right Hon. W.L. MacKenzie King, M.P. Prime Minister of Canada – City of Vancouver Archives |url=https://searcharchives.vancouver.ca/canada-and-war-manpower-and-total-war-effort-national-selctive-service-broadcast-by-right-hon-w-l-mackenzie-king-m-p-prime-minister-of-canada |access-date=13 February 2023 |website=searcharchives.vancouver.ca}}</ref> Meighen failed to win his seat in by-election in 1942, and the issue subsided for a short time. But eventually, national conscription was introduced in Canada in 1944, as well as dramatically increased taxation, another symbol of the "total war effort". |

|||

=====Soviet Union===== |

|||

==Quotes== |

|||

[[File:RIAN archive 216 The Volkovo cemetery.jpg|thumb|Three men burying victims of [[siege of Leningrad|Leningrad's siege]], in which about 1 million civilians died]] |

|||

{{wikiquote}} |

|||

* "...There is another more obvious difference from 1914. The whole of the warring nations are engaged, not only soldiers, but the entire population, men, women and children. The fronts are everywhere. The trenches are dug in the towns and streets. Every village is fortified. Every road is barred. The front line runs through the factories. the workmen are soldiers with different weapons but the same courage...". ''[[Winston Churchill]] on the Radio, [[June 18]] ; and [[House of Commons]] [[20 August]], [[1940]].[http://www.winstonchurchill.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=420]'' |

|||

The Soviet Union (USSR) was a [[planned economy|command economy]] which already had an economic and legal system allowing the economy and society to be redirected into fighting a total war. The transportation of factories and whole labour forces east of the [[Urals]] as the Germans advanced across the USSR in 1941 was an impressive feat of planning. Only those factories which were useful for war production were moved because of the total war commitment of the Soviet government.{{Citation needed|date=March 2021}} |

|||

* "I ask you: Do you want total war? If necessary, do you want a war more total and radical than anything that we can even imagine today?" ''Nazi propaganda minister [[Joseph Goebbels]] [[18 February]] [[1943]] in his [[Sportpalast speech]].'' |

|||

The Eastern Front of the [[European Theatre of World War II]] encompassed the conflict in [[central Europe|central]] and [[eastern Europe]] from 22 June 1941, to 9 May 1945. It was the largest theatre of war in history in terms of numbers of soldiers, equipment and [[World War II casualties|casualties]] and was notorious for its unprecedented ferocity, destruction, and immense loss of life (see [[World War II casualties]]). The fighting involved millions of [[Nazi army|German]], Hungarian, Romanian and [[Red army|Soviet]] troops along a broad front hundreds of kilometres long. It was by far the deadliest single theatre of World War II. Scholars now believe that at most 27 million Soviet citizens died during the war, including at least 8.7 million soldiers who fell in battle against [[Hitler]]'s armies or died in [[POW]] camps. Millions of civilians died from [[starvation]], exposure, atrocities, and massacres.<ref>{{cite news |url= http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/4530565.stm |work= BBC.co.uk |title= Leaders mourn Soviet wartime dead |access-date= 5 August 2015|date= 9 May 2005 }}</ref> The Axis lost over 5 million soldiers in the east as well as many thousands of civilians.<ref>German losses according to: Rüdiger Overmans, ''Deutsche militärische Verluste im Zweiten Weltkrieg''. Oldenbourg 2000. {{ISBN|978-3-486-56531-7}}, pp. 265, 272</ref> |

|||

* "Actually [[Bombing of Dresden in World War II|Dresden]] was a mass of munitions works, an intact government centre, and a key transportation point to the East. It is now none of these things." ''Written by Air Marshal Harris in a memo to the Air Ministry on [[29 March]] [[1945]].'' |

|||

During the [[Battle of Stalingrad]], newly built [[T-34 tank]]s were driven—unpainted because of a paint shortage—from the factory floor straight to the front. <!-- World at War series not sure which programme number-->This came to symbolise the USSR's commitment to a policy of total war.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Beevor |first=Antony |title=Stalingrad |publisher=Penguin books |year=1999 |isbn=0-14-024985-0 |page=110}}</ref>{{dubious|date=September 2020}} |

|||

* ''Chorus from a popular WWII British song'': + |

|||

::It's a ticklish sort of job making a thing for a thing-ummy-bob |

|||

=====United States===== |

|||

::Especially when you don't know what it's for |

|||

{{Main|United States home front during World War II}} |

|||

::But it's the girl that makes the thing that drills the hole |

|||

The United States underwent an unprecedented mobilisation of national resources for the Second World War, creating a [[military-industrial complex]] that still exists. Although the United States was not in danger of an existential attack, the national sense after Pearl Harbor was to use all the nation's resources to defeat Germany and Japan. Most non-essential activities were rationed, prohibited or restrained, and most of the fit unmarried young men were drafted. There was little urgency before 1940, when the collapse of France ended the [[Phoney War]] and revealed urgent needs. Nevertheless, President Franklin Roosevelt moved to first solidify public opinion before acting. In 1940 the first peacetime draft was instituted, along with [[Lend-Lease]] programs to aid the British, and covert aid was passed to the Chinese as well.<ref>James MacGregor Burns, ''Roosevelt: The soldier of freedom (1940–1945). Vol. 2'' (1970) pp. 3–63. [https://archive.org/details/rooseveltsoldier0000burn online]</ref> |

|||

::that holds the spring that works the thing-ummy-bob |

|||

American [[public opinion]] was still opposed to involvement in the problems of Europe and Asia, however. In 1941, the Soviet Union became the latest nation to be invaded, and the U.S. gave its aid as well. American ships began defending aid convoys to the Allied nations against submarine attacks, and a total trade embargo against the [[Empire of Japan]] was instituted to deny its military the raw materials its factories and military forces required to continue its offensive actions in China. |

|||

::that makes the engines roar. |

|||

::And it's the girl that makes the thing that holds the oil |

|||

In late 1941, Japan's [[Imperial Japanese Army|Army]]-dominated government decided to seize by military force the strategic resources of South-East Asia and Indonesia since the Western powers would not give Japan these goods by trade. Planning for this action included [[surprise attack]]s on American and British forces in Hong Kong, the Philippines, Malaya, and the U.S. naval base and warships at [[Pearl Harbor]]. In response to these attacks, the UK and U.S. declared war the next day. [[Nazi Germany]] declared war on the U.S. a few days later, along with [[Kingdom of Italy#Fascist regime (1922–1943)|Fascist Italy]]; the U.S. found itself fully involved in a second [[world war]]. |

|||

::that oils the ring that works the thing-ummy-bob |

|||

::that's going to win the war. |

|||

As the United States began to gear up for a major war, information and propaganda efforts were set in motion. Civilians (including children) were encouraged to take part in fat, grease, and scrap metal collection drives. Many factories making non-essential goods retooled for war production. Levels of industrial productivity previously unheard of were attained during the war; multi-thousand-ton convoy ships were routinely built in a month and a half, and tanks poured out of the former automobile factories. Within a few years of the U.S. entry into the Second World War, nearly every man without children fit for service, between 18 and 30, was conscripted into the military "for the duration" of the conflict, and unprecedented numbers of women took up jobs previously held by them. Strict systems of rationing of consumer staples were introduced to redirect productive capacity to war needs.<ref>John Phillips Resch, and D'Ann Campbell eds. ''Americans at War: Society, Culture, and the Homefront'' (vol 3, 2004).</ref> |

|||

Previously untouched sections of the nation mobilised for the war effort. Academics became technocrats; home-makers became bomb-makers (massive numbers of women worked in industry during the war); union leaders and businessmen became commanders in the massive armies of production. The great scientific communities of the United States were mobilised as never before, and mathematicians, doctors, engineers, and chemists turned their minds to the problems ahead of them.<ref>Arthur Herman, ''Freedom's Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II'' (Random House, 2012).</ref> |

|||

By the war's end, a multitude of advances had been made in medicine, physics, engineering, and the other sciences. This included the efforts of the [[theoretical physics|theoretical physicists]] working at the [[Los Alamos National Laboratory]] on the [[Manhattan Project]], which led to the [[Trinity (nuclear test)|Trinity nuclear test]] and thus brought about the [[Atomic Age]]. |

|||

In the war, the United States lost 407,316 military personnel, but had managed to avoid the extensive level of damage to civilian and industrial infrastructure that other participants suffered. The U.S. emerged as one of the two [[superpower]]s after the war.<ref>{{Cite book|title=The world since 1945: a history of international relations|last=McWilliams|first=Wayne|publisher=Lynne Rienner Publishers|year=1990}}</ref> |

|||

=====Unconditional surrender===== |

|||

{{off topic|date=January 2020}}{{Main|Unconditional surrender}} |

|||

{{Blockquote|Actually [[Bombing of Dresden in World War II|Dresden]] was a mass of munitions works, an intact government centre, and a key transportation point to the East. It is now none of these things.|source=Air Chief Marshal [[Arthur Harris]], in a memo to the [[Air Ministry]] on 29 March 1945<ref>Longmate, Norman; ''The Bombers'', Hutchins & Co, (1983), {{ISBN|978-0-09-151580-5}} p. 346</ref>}} |

|||

After the United States entered World War II, [[Franklin D. Roosevelt]] declared at [[Casablanca conference]] to the other Allies and the press that [[unconditional surrender]] was the objective of the war against the Axis Powers of Germany, Italy, and Japan.<ref name="SOSCasablanca">{{cite web|title=The Casablanca Conference, 1943|url=https://history.state.gov/milestones/1937-1945/casablanca|website=Office of the Historian|publisher=United States Department of State|access-date=19 January 2017}}</ref> Prior to this declaration, the individual regimes of the Axis Powers could have negotiated an [[armistice]] similar to that at the end of World War I and then a conditional surrender when they perceived that the war was lost. |

|||

The unconditional surrender of the major Axis powers caused a legal problem at the post-war [[Nuremberg Trials]], because the trials appeared to be in conflict with Articles 63 and 64 of the [[Geneva Convention on Prisoners of War (1929)|Geneva Convention of 1929]]. Usually if such trials are held, they would be held under the auspices of the defeated power's own legal system as happened with some of the minor Axis powers, for example in the post World War II [[Romanian People's Tribunals]]. To circumvent this, the Allies argued that the major [[war criminals]] were captured after the end of the war, so they were not prisoners of war and the Geneva Conventions did not cover them. Further, the collapse of the Axis regimes created a legal condition of total defeat (''[[debellatio]]'') so the provisions of the [[Hague Convention of 1907|1907 Hague Convention]] over [[military occupation]] were not applicable.<ref>Ruth Wedgwood {{cite web |url=http://www.sais-jhu.edu/pubaffairs/SAISarticles04/Wedgwood_WSJ_111604.pdf |title=Judicial Overreach |access-date=29 May 2008 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080308191908/http://www.sais-jhu.edu/pubaffairs/SAISarticles04/Wedgwood_WSJ_111604.pdf |archive-date=8 March 2008 }} [[The Wall Street Journal]] 16 November 2004</ref> |

|||

===Post-World War II=== |

|||

{{See also|Proxy war|Coercive diplomacy|Deterrence theory}} |

|||

Since the end of World War II, no industrial nation has fought such a large, decisive war.<ref name="GWUniversityWWII">{{cite web|title=World War II (1939–1945)|url=https://www2.gwu.edu/~erpapers/teachinger/glossary/world-war-2.cfm|website=The Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project|publisher=George Washington University|access-date=19 January 2017}}</ref> This is likely due to the availability of nuclear weapons, whose destructive power and quick deployment render a full mobilisation of a country's resources such as in World War II logistically impractical and strategically irrelevant.{{sfn|Baylis|Wirtz|Gray|2012|p=55}} |

|||

By the end of the 1950s, the [[ideology|ideological]] stand-off of the [[Cold War]] between the [[Western world]] and the [[Soviet Union]] had resulted in thousands of nuclear weapons being aimed by each side at the other. Strategically, the equal balance of destructive power possessed by each side manifests in the doctrine of [[Mutual assured destruction|mutually assured destruction]] (MAD), which determines that a nuclear attack by one superpower would result in a nuclear counter-strike by the other.<ref name="BBCMAD">{{cite news|last1=Castella|first1=Tom de|title=How did we forget about mutually assured destruction?|url=https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-17026538|access-date=19 January 2017|work=BBC News|date=15 February 2012|language=en}}</ref> This would result in hundreds of millions of deaths in a world where, in words widely attributed to [[Nikita Khrushchev]], "The living will envy the dead".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.bartleby.com/73/1257.html|title=1257. Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (1894–1971). Respectfully Quoted: A Dictionary of Quotations. 1989|access-date=5 August 2015}}</ref> |

|||

During the Cold War, the two [[superpower]]s sought to avoid open conflict between their respective forces, as both sides recognised that such a clash could very easily escalate, and quickly involve nuclear weapons. Instead, the superpowers fought each other through their involvement in proxy wars, military buildups, and diplomatic standoffs. |

|||

In the case of proxy wars, each superpower supported its respective allies in conflicts with forces aligned with the other superpower, such as in the [[Vietnam War]] and the [[Soviet invasion of Afghanistan]]. |

|||

The following post-World War II conflicts have been characterized as "total war": |

|||

* [[1948 Arab–Israeli War]] (1948–1949)<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Naor |first=Moshe |date=2008 |title=Israel's 1948 War of Independence as a Total War |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/30036505 |journal=Journal of Contemporary History |volume=43 |issue=2 |pages=241–257 |doi=10.1177/0022009408089031 |jstor=30036505 |s2cid=159808983 |issn=0022-0094}}</ref> |

|||

* [[Iran–Iraq War]] (1980–1988)<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Farzanegan |first1=Mohammad Reza |last2=Gholipour |first2=Hassan F. |date=November 2021 |title=Growing up in the Iran–Iraq war and preferences for strong defense |journal=Review of Development Economics |language=en |volume=25 |issue=4 |pages=1945–1968 |doi=10.1111/rode.12806 |issn=1363-6669 |quote=it was a total war and it included three modes of warfare not observed in previous wars since 1945: indiscriminate ballistic missile attacks on cities from both sides, but mainly by Iraq; the significant use of chemical weapons by Iraq; and approximately 520 attacks on third-country oil tankers in the Persian Gulf.|doi-access=free |hdl=10419/284793 |hdl-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

* [[Russian invasion of Ukraine]] (2022–present)<ref name="RUSItotalwar">{{cite web |title=Russian Total War in Ukraine: Challenges and Opportunities |url=https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/russian-total-war-ukraine-challenges-and-opportunities |access-date=19 March 2023 |website=RUSI}}</ref> |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

* [[The bomber will always get through]] |

|||

[[Conscription]], [[Nation in arms]], [[levée en masse]],[[bombing of Dresden]] |

|||

* [[Conventional warfare]] |

|||

* [[Economic warfare]] |

|||

* [[Roerich Pact]] |

|||

* [[War economy]] |

|||

* [[War of annihilation]] |

|||

==References== |

|||

[[Category:War]] |

|||

{{Reflist}} |

|||

[[Category:Military doctrines]] |

|||

===Bibliography=== |

|||

<!-- interwiki --> |

|||

{{refbegin|30em}} |

|||

* Barnhart, Michael A. ''Japan prepares for total war: The search for economic security, 1919–1941'' (Cornell UP, 2013). |

|||

* {{Citation |editor1-last=Baylis |editor1-first=John |editor2-last=Wirtz |editor2-first=James J. |editor3-last=Gray |editor3-first=Colin S. |year=2012 |title=Strategy in the Contemporary World |edition=4th, illustrated |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-969478-5 |page=[https://books.google.com/books?id=njK0CuHhQkIC&pg=PA55 55]}} |

|||

* Barrett, John G. "Sherman and Total War in the Carolinas." ''North Carolina Historical Review'' 37.3 (1960): 367–381. [https://www.jstor.org/stable/23517035 online] |

|||

* {{Citation |first=David A. |last=Bell |title=The First Total War: Napoleon's Europe and the Birth of Warfare as We Know It |year=2007}} |

|||

* Black, Jeremy. ''The age of total war, 1860–1945'' (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2010). |

|||

* Broers, Michael. "The Concept of Total War in the Revolutionary – Napoleonic Period." ''War in History'' 15.3 (2008): 247–268. |

|||

* Craig, Campbell. ''Glimmer of a new Leviathan: Total war in the realism of Niebuhr, Morgenthau, and Waltz'' (Columbia University Press, 2004), Intellectual history. |

|||

* {{cite journal |journal=Baltic Security & Defence Review |volume=15 |issue=2 |date=2013 |title=Coping with a New Security Situation – Swedish Military Attachés in the Baltic 1919–1939 |first=Fredrik |last=Eriksson |pages=33–69 |url=https://www.baltdefcol.org/files/files/BSDR/BSDR_15_2.pdf}} |

|||

* Fisher, Noel C. "'Prepare Them For My Coming': General William T. Sherman, Total War, and Pacification in West Tennessee." ''Tennessee Historical Quarterly'' 51.2 (1992): 75–86. |

|||

* Förster, Stig, and Jorg Nagler. ''On the Road to Total War: The American Civil War and the German Wars of Unification, 1861–1871'' (Cambridge University Press, 2002). |

|||

* Hewitson, Mark. "Princes’ Wars, Wars of the People, or Total War? Mass Armies and the Question of a Military Revolution in Germany, 1792–1815." ''War in History'' 20.4 (2013): 452–490. |

|||

* Hoffman, Christopher S. ''Major General William T. Sherman's total war in the Savannah and Carolina campaigns'' (US Army Command and General Staff College, School for Advanced Military Studies Fort Leavenworth, 2018) [https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD1071091.pdf online]. |

|||

* Hsieh, Wayne Wei-Siang. "Total War and the American Civil War Reconsidered: The End of an Outdated" Master Narrative"." ''Journal of the Civil War Era'' 1.3 (2011): 394–408. [https://www.jstor.org/stable/26070141 online] |

|||

* {{Citation |first1=Eric |last1=Markusen |first2=David |last2=Kopf |title=The Holocaust and Strategic Bombing: Genocide and Total War in the Twentieth Century |year=1995}} |

|||

* Marwick, Arthur, Clive Emsley, and Wendy Simpson. ''Total war and historical change: Europe 1914–1955'' (Open University Press, 2001). |

|||

* {{Citation |first=Mark E. Jr. |last=Neely |title=Was the Civil War a Total War? |journal=Civil War History |volume=50 |page=2004}} |

|||

* Royster, Charles. ''The Destructive War: William Tecumseh Sherman, Stonewall Jackson, and the Americans'' (1993) |

|||

* {{Citation |first1=Daniel E. |last1=Sutherland |first2=Grady |last2=McWhiney |title=The Emergence of Total War |year=1998 |series=US Civil War Campaigns and Commanders Series}} |

|||

* Walters, John Bennett. "General William T. Sherman and total war." ''Journal of Southern History'' 14.4 (1948): 447–480. [https://www.jstor.org/stable/2198124 online] |

|||

** Walters, John Bennett. ''Merchant of terror: General Sherman and total war'' (1973); adds nothing new says John F. Marszalek, ''Journal of American History'' (Dec. 1974), pp. 784–785. |

|||

{{refend}} |

|||

==External links== |

|||

[[de:Totaler Krieg]] |

|||

* [https://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/30036505?sid=21105087950491&uid=2&uid=4 Israel's 1948 War of Independence as a Total War] |

|||

[[hr:Totalni rat]] |

|||

* [https://archive.org/details/cu31924095654384 A collection of papers relating to the Sullivan Expedition] |

|||

[[ja:国家総力戦]] |

|||

* Daniel Marc Segesser: [https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/controversy_total_war/ Controversy: Total War], in: [https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/home.html/ 1914–1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War]. |

|||

[[nl:Totale oorlog]] |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Total War}} |

|||

[[Category:Wars by type]] |

|||

[[Category:Warfare by type]] |

|||

[[Category:Military doctrines]] |

|||

[[Category:Economic warfare]] |

|||

[[Category:Military economics]] |

|||

[[Category:Military science]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 19:31, 3 May 2024

| Part of a series on |

| War |

|---|

|

Total war is a type of warfare that includes any and all civilian-associated resources and infrastructure as legitimate military targets, mobilises all of the resources of society to fight the war, and gives priority to warfare over non-combatant needs.

The term has been defined as "A war that is unrestricted in terms of the weapons used, the territory or combatants involved, or the objectives pursued, especially one in which the laws of war are disregarded."[1]

In the mid-19th century, scholars identified total war as a separate class of warfare. In a total war, the differentiation between combatants and non-combatants diminishes due to the capacity of opposing sides to consider nearly every human, including non-combatants, as resources that are used in the war effort.[2]

Characteristics[edit]