Urban heat island: Difference between revisions

→External links: {{Global warming}} |

→Relation to global warming: L's comments have absolutely nothing to do with UHI. the inclusion is absurd. |

||

| Line 86: | Line 86: | ||

Another view, often held by skeptics of [[global warming]], is that the heat island effect accounts for much or nearly all warming recorded by land-based thermometers. However, these views are mainly presented in "popular literature" and there are no known scientific peer-reviewed papers holding this view. Some have argued for an ill-defined "influence" of the UHI on the temperature records without attempting to quantify it - for example [[Richard Lindzen]] in 1990.<ref>[http://eaps.mit.edu/faculty/lindzen/cooglobwrm.pdf eaps.mit.edu]</ref> |

Another view, often held by skeptics of [[global warming]], is that the heat island effect accounts for much or nearly all warming recorded by land-based thermometers. However, these views are mainly presented in "popular literature" and there are no known scientific peer-reviewed papers holding this view. Some have argued for an ill-defined "influence" of the UHI on the temperature records without attempting to quantify it - for example [[Richard Lindzen]] in 1990.<ref>[http://eaps.mit.edu/faculty/lindzen/cooglobwrm.pdf eaps.mit.edu]</ref> |

||

More recently (2006) Lindzen, who still opposes the idea that humans have caused global warming, has acknowledged that the warming itself is real: |

|||

:''"First, let's start where there is agreement. The public, press and policy makers have been repeatedly told that three claims have widespread scientific support: Global temperature has risen about a degree since the late 19th century; levels of CO2 in the atmosphere have increased by about 30% over the same period; and CO2 should contribute to future warming. These claims are true."''<ref>[http://www.opinionjournal.com/extra/?id=110008220 opinionjournal.com]</ref> |

|||

== References == |

== References == |

||

Revision as of 09:17, 14 May 2007

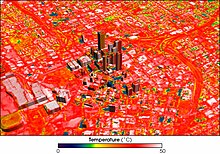

An urban heat island (UHI) is a metropolitan area which is significantly warmer than its surroundings. As population centres grow in size from village to town to city, they tend to have a corresponding increase in average temperature, which is more often welcome in winter months than in summertime. The EPA says: "On hot summer days, urban air can be 2-10°F [2-6°C] hotter than the surrounding countryside. Not to be confused with global warming, scientists call this phenomenon the 'urban heat island effect'."[1]

There is no controversy about cities generally tending to be warmer than their surroundings. What is controversial about these heat islands is whether, and if so how much, this additional warmth affects trends in (global) temperature record. The current state of the science is that the effect on the global temperature trend is negligible, the IPCC says: Urban heat island effects are real but local, and have a negligible influence (less than 0.006°C per decade over land and zero over the oceans) on these values.[2]

Scientists compiling the historical temperature record are aware of the UHI effect, but they vary as to how significant they think it is. Some scientists (see Peterson, below) have published peer reviewed papers indicating that the effect of the UHI has been overestimated, and that it does not affect the record at all. Other scientists have used various methods to compensate for it. Some advocates charge that temperature data from heat islands has been mistakenly used as evidence for global warming.

As a result of the urban heat island effect, monthly rainfall is about 28% greater between 20-40 miles downwind of cities, compared with upwind.[3]

Causes

There are several causes of a UHI, as outlined in Oke (1982). The principal reason for the night-time warming is (comparatively warm) buildings blocking the view to the (relatively cold) night sky. (See Thermal radiation) Two other reasons that UHIs occur are changes in the thermal properties of surface materials and lack of evapotranspiration in urban areas. Materials commonly used in urban areas, such as concrete and asphalt, have significantly different thermal bulk properties (including heat capacity and thermal conductivity) and surface radiative properties (albedo and emissivity) than the surrounding rural areas. This initiates a change in the energy balance of the urban area, often causing it to reach higher temperatures (measured both on the surface and in the air) than its surroundings. The energy balance is also affected by the lack of vegetation and standing water in urban areas, which inhibits cooling by evapotranspiration.

Other causes of a UHI are due to geometric effects. The tall buildings within many urban areas provide multiple surfaces for the reflection and absorption of sunlight, increasing the efficiency with which urban areas are heated. This is called the "canyon effect". Another effect of buildings is the blocking of wind, which also inhibits cooling by convection.

Some causes of a UHI are anthropogenic, though they are relatively minor in summer and generally in low- and mid-latitude areas. In winter and especially in high latitudes, when solar radiation is considerably smaller, these effects can contribute the majority of UHI. As urban areas are often inhabited by large numbers of people, heat generation by human activity also contributes to the UHI. Such activities include the operation of automobiles, air conditioning units, and various forms of industry. High levels of pollution in urban areas can also increase the UHI, as many forms of pollution can create a local greenhouse effect.

Different climatic regions may have very different experiences of UHIs. In an already warm area they will be unwelcome; in a cold area they might be beneficial.

The EPA discusses one of the reasons when it says:

- Heat islands form as vegetation is replaced by asphalt and concrete for roads, buildings, and other structures necessary to accommodate growing populations. These surfaces absorb - rather than reflect - the sun's heat, causing surface temperatures and overall ambient temperatures to rise.

The lesser-used term heat island refers to any area, populated or not, which is consistently hotter than the surrounding area.

Some cities exhibit a heat island effect, largest at night (see below), and particularly in summer,[4] or perhaps in winter,[5] with several degrees between the center of the city and surrounding fields. The difference in temperature between an inner city and its surrounding suburbs is frequently mentioned in weather reports: e.g., "68 degrees downtown, 64 in the suburbs."

Significance

Urban heat islands are of interest primarily because they affect so many people. According to estimates by the United Nations, nearly half of the world's population currently live in urban areas. Within western nations, this number can approach 75%. The impact of UHIs on the world's populace has the potential to be large and far-reaching.

UHIs have the potential to directly influence the health and welfare of urban residents. Within the United States alone, an average of 1000 people die each year due to extreme heat, more than due to all other weather events combined (Changnon et al., 1996). As UHIs are characterized by increased temperature, they can potentially increase the magnitude and duration of heat waves within cities. Research has found that the mortality rate during a heat wave increases exponentially with the maximum temperature (Buechley et al., 1972), an effect that is exacerbated by the UHI. The nighttime effect of UHIs (discussed below) can be particularly harmful during a heat wave, as it deprives urban residents of the cool relief found in rural areas during the night (Clarke, 1972).

Research in the United States suggests that the relationship between extreme temperature and mortality in the U.S. varies by location. According to the Program on Health Effects of Global Environmental Change at Johns Hopkins University (JHU), heat is most likely to increase the risk of mortality in cities at mid-latitudes and high latitudes with significant annual temperature variation. For example, when Chicago and New York experience unusually hot summertime temperatures, elevated levels of illness and death are predicted. In contrast, parts of the country that are mild to hot year-round have a lower public health risk from excessive heat. JHU research shows that residents of southern cities, such as Miami, tend to be acclimated to hot weather conditions and therefore less vulnerable.

Another consequence of urban heat islands is the increased energy required for air conditioning and refrigeration in cities that are in comparatively hot climates. The Heat Island Group estimates that the heat island effect costs Los Angeles about $100 million per year in energy. Conversely, those that are in cold climates such as Chicago would presumably need somewhat less in the way of heating.

Aside from the obvious effect on temperature, UHIs can produce secondary effects on local meteorology, including the altering of local wind patterns, the development of clouds and fog, the number of lightning strikes, and the rates of precipitation.

Using satellite images, researchers discovered that city climates have a noticeable influence on plant growing seasons up to 10 kilometers (6 miles) away from a city’s edges. Growing seasons in 70 cities in eastern North America were about 15 days longer in urban areas compared to rural areas outside of a city’s influence.[6][7]

Mitigation

The heat island effect can be counteracted slightly by using white or reflective materials to build houses, pavements, and roads, thus increasing the overall albedo of the city. This is a long established practice in many countries. A second option is to increase the amount of well-watered vegetation. These two options can be combined with the implementation of green roofs.

Diurnal behavior

The IPCC states that "it is well-known that compared to non-urban areas urban heat islands raise night-time temperatures more than daytime temperatures."[8] For example, Moreno-Garcia (Int. J. Climatology, 1994) found that Barcelona was 0.2°C cooler for daily maxima and 2.9°C warmer for minima than a nearby rural station. In fact, a description of the very first report of the UHI by Luke Howard in 1820 says:

- Howard was also to discover that the urban center was warmer at night than the surrounding countryside, a condition we now call the urban heat island. Under a table presented in The Climate of London (1820), of a nine-year comparison between temperature readings in London and in the country, he commented: "Night is 3.70° warmer and day 0.34° cooler in the city than in the country." He attributed this difference to the extensive use of fuel in the city.[9]

Though the air temperature UHI is generally most apparent at night, urban heat islands exhibit significant and somewhat paradoxical diurnal behavior. The air temperature UHI is large at night and small during the day, while the opposite is true for the surface temperature UHI. From Roth et al. (1990):

- Nocturnal urban–rural differences ... in surface temperatures are much smaller than in the day-time. This is the reverse of the case for near-surface air temperatures.

Throughout the daytime, particularly when the skies are free of clouds, urban surfaces are warmed by the absorption of solar radiation. As described above, the surfaces in the urban areas tend to warm faster than those of the surrounding rural areas. By virtue of their high heat capacities, these urban surfaces act as a giant reservoir of heat energy. (For example, concrete can hold roughly 2000 times as much heat as an equivalent volume of air.) As a result, the large daytime surface temperature UHI is easily seen via thermal remote sensing (e.g. Lee, 1993).

However, as is often the case with daytime heating, this warming also has the effect of generating convective winds within the urban boundary layer. It is theorized that, due to the atmospheric mixing that results, the air temperature UHI is generally minimal or nonexistent during the day, though the surface temperatures can reach extremely high levels (Camilloni and Barros, 1997).

At night, however, the situation reverses. The absence of solar heating causes the atmospheric convection to decrease, and the urban boundary layer begins to stabilize. If enough stablization occurs, an inversion layer is formed. This traps the urban air near the surface, and allows it to heat from the still-warm urban surfaces, forming the nighttime air temperature UHI.

The explanation for the night-time maximum is that the principal cause of UHI is blocking of "sky view" during cooling: surfaces lose heat at night principally by radiation to the (comparatively cold) sky, and this is blocked by the buildings in an urban area. Radiative cooling is more dominant when wind speed is low and the sky is cloudless, and indeed the UHI is found to be largest at night in these conditions.[10][11]

Relation to global warming

Because some parts of some cities may be several degrees hotter than their surroundings, a difference double or triple the warming observed over the historical temperature record, there is a risk that the effects of urban sprawl might be misinterpreted as an increase in global temperature. However, the fact that heat islands have such a large effect is, paradoxically, evidence that it is largely absent from the record, otherwise warming would be shown as much larger in the record. The 'heat island' warming does unquestionably affect cities and the people who live in them, but it is not at all clear that it biases trends in historical temperature record: for example, urban and rural trends are very similar.

The IPCC says:

- However, over the Northern Hemisphere land areas where urban heat islands are most apparent, both the trends of lower-tropospheric temperature and surface air temperature show no significant differences. In fact, the lower-tropospheric temperatures warm at a slightly greater rate over North America (about 0.28°C/decade using satellite data) than do the surface temperatures (0.27°C/decade), although again the difference is not statistically significant.[12]

Note that not all cities show a warming relative to their rural surroundings. For example, Hansen et al. (JGR, 2001) adjusted trends in urban stations around the world to match rural stations in their regions, in an effort to homogenise the temperature record. Of these adjustments, 42% warmed the urban trends: which is to say that in 42% of cases, the cities were getting cooler relative to their surroundings rather than warmer. One reason is that urban areas are heterogeneous, and weather stations are often sited in "cool islands" - parks, for example - within urban areas.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which has issued several influential reports on climate trends, says that the effects of urban heat islands on the recorded temperature "do not exceed about 0.05°C over the period 1900 to 1990." Note that this is a maximum: it does not exclude zero influence. This statement rests on various sources, contributing reasons being:[13]

- land, sea, and borehole records are in reasonable agreement over the last century. (Much more heat has gone into the earth and the ocean depths than remains in the wispy atmosphere, and the ocean and borehole records have not been questioned.)[14]

- the trends in urban stations for 1951 to 1989 (0.10°C/decade) are not greatly more than those for all land stations (0.09°C/decade).

- similarly the rural trend is 0.70°C/century from 1880 to 1998, which is actually larger than the full station trend (0.65°C/century).[15]

- the differences in trend between rural and all stations are also virtually unaffected by elimination of areas of largest temperature change, like Siberia, because such areas are well represented in both sets of stations.

- Over the Northern Hemisphere land areas where urban heat islands are most apparent the trends of lower-tropospheric temperature and surface air temperature show no significant differences. In fact, the lower-tropospheric temperatures warm at a slightly greater rate over North America (about 0.28°C/decade using satellite data) than do the surface temperatures (0.27°C/decade).[16]

A 2003 paper ("Assessment of urban versus rural in situ surface temperatures in the contiguous United States: No difference found"; J climate; Peterson; 2003) indicates that the effects of the urban heat island may have been overstated, finding that "Contrary to generally accepted wisdom, no statistically significant impact of urbanization could be found in annual temperatures." This was done by using satellite-based night-light detection of urban areas, and more thorough homogenisation of the time series (with corrections, for example, for the tendency of surrounding rural stations to be slightly higher, and thus cooler, than urban areas). As the paper says, if its conclusion is accepted, then it is necessary to "unravel the mystery of how a global temperature time series created partly from urban in situ stations could show no contamination from urban warming." The main conclusion is that micro- and local-scale impacts dominate the meso-scale impact of the urban heat island: many sections of towns may be warmer than rural sites, but meteorological observations are likely to be made in park "cool islands."

A study by David Parker published in Nature in November 2004 attempts to test the urban heat island theory, by comparing temperature readings taken on calm nights with those taken on windy nights. If the urban heat island theory is correct then instruments should have recorded a bigger temperature rise for calm nights than for windy ones, because wind blows excess heat away from cities and away from the measuring instruments. There was no difference between the calm and windy nights, and the author says: we show that, globally, temperatures over land have risen as much on windy nights as on calm nights, indicating that the observed overall warming is not a consequence of urban development.[17][18]

Another view, often held by skeptics of global warming, is that the heat island effect accounts for much or nearly all warming recorded by land-based thermometers. However, these views are mainly presented in "popular literature" and there are no known scientific peer-reviewed papers holding this view. Some have argued for an ill-defined "influence" of the UHI on the temperature records without attempting to quantify it - for example Richard Lindzen in 1990.[19]

References

- ^ yosemite.epa.gov

- ^ ipcc.ch

- ^ guardian.co.uk

- ^ home.pusan.ac.kr

- ^ geography.uc.edu

- ^ eobglossary.gsfc.nasa.gov

- ^ nasa.gov

- ^ grida.no

- ^ islandnet.com

- ^ earthsci.unimelb.edu.au

- ^ ams.confex.com

- ^ grida.no

- ^ grida.no

- ^ grida.no

- ^ (Peterson et al., GRL, 1999)

- ^ grida.no

- ^ nature.com

- ^ news.bbc.co.uk

- ^ eaps.mit.edu

- R. W. Buechley, J. Van Bruggen, and L. E. Trippi (1972). "Heat island = death island?". Environmental Research. 5: 85–92.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - I. Camilloni and V. Barros (1997). "On the urban heat island effect dependence on temperature trends". Climatic Change. 37: 665–681.

- S. A. Changnon, Jr., K. E. Kunkel, and B. C. Reinke (1996). "Impacts and responses to the 1995 heat wave: A call to action". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 77: 1497–1506.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - J. F. Clarke (1972). "Some effects of the urban structure on heat mortality". Environmental Research. 5: 93–104.

- Helmut E. Landsberg (1981). The Urban Climate. New York: Academic Press. 0124359604.

- H.-Y. Lee (1993). "An application of NOAA AVHRR thermal data to the study or urban heat islands". Atmospheric Environment. 27B: 1–13.

- T. R. Oke (1982). "The energetic basis of the urban heat island". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. 108: 1–24.

- David E. Parker (2004). "Climate: Large-scale warming is not urban". Nature. 432: 290.

- Thomas C. Peterson (2003). "Assessment of Urban Versus Rural In Situ Surface Temperatures in the Contiguous United States: No Difference Found". Journal of Climate. 16: 2941–2959. [1]

- M. Roth, T. R. Oke, and W. J. Emery (1989). "Satellite-derived urban heat islands from three coastal cities and the utilization of such data in urban climatology". International Journal of Remote Sensing. 10: 1699–1720.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- Land-Surface Air Temperature - from the IPCC

- Urban Heat Islands and Climate Change - from the University of Melbourne, Australia

- The Surface Temperature Record and the Urban Heat Island From RealClimate.org

- NASA Earth Observatory: The Earth's Big Cities, Urban Heat Islands

- Research and mitigation strategies on UHI - US EPA designated, National Center of Excellence on SMART Innovations at Arizona State University